Structured Summary

Introduction:

Rates of overweight and obesity among Active Duty Military Personnel remain high despite fitness test requirements, negative consequences of fitness test failure, and emphasis on weight and appearance standards. Specific motivating factors for weight loss influence weight loss program interest and often differ by gender, race, ethnicity, or age. This study investigates the weight loss motivations endorsed by a diverse population of Active Duty Military Personnel initiating a behavioral weight loss study, in order to inform the development of future recruitment efforts and program development.

Materials and Methods:

Active Duty Military Personnel (n= 248) completed a 16-item questionnaire of weight loss motivations prior to initiating a behavioral weight loss study. We evaluated endorsement patterns by demographic characteristics (body mass index, gender, race, ethnicity, age, and military rank). Data collection for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Wilford Hall and acknowledged and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tennessee Health Sciences.

Results:

Results indicated that improved physical health, improved fitness, improved quality of life, and to live long were endorsed as “very important” motivations by at least three-fourths of the sample. ‘To pass the fitness test’ was endorsed less frequently as a “very important” motivation, by 69% of the sample. A greater proportion of women as compared to men endorsed being very motivated by improving mood/wellbeing, quality of life, physical mobility, job performance, appearance, and sex life, as well as fitting into clothes. Participants categorized in the “Other” racial group and African Americans more frequently endorsed motivations to improve fitness and physical strength when compared to Caucasians. Moreover, participants in the “Other” race category were significantly more likely to rate their ability to physically defend themselves, improve physical mobility and improve interactions with friends as motivators. Participants who identified as Hispanic endorsed significantly higher frequency of being motivated to improve their ability to physically defend themselves, interactions with friends, physical mobility, and sex life compared to those who identified as Non-Hispanic. A significantly greater percentage of officers of lower rank (i.e., O1–3) endorsed being motivated to improve their quality of life. Improving confidence was a significant motivator for younger and lower ranking enlisted personnel (i.e. E1–4). Younger participants were also significantly more likely to want to improve their ability to physically defend themselves.

Conclusion:

We conclude that overweight and obese Military Personnel are motivated by various reasons to engage in weight loss, including their military physical fitness test. Findings may assist the development of recruitment efforts or motivationally-focused intervention materials for weight loss interventions tailored for the diverse population of Active Duty Military Personnel.

Keywords: motivations, weight loss, body mass index, military

Introduction

Despite mandatory, recurring fitness testing and biometric assessment, half of Military Personnel are classified as overweight and approximately 12% of Military Personnel are obese,1 with service members aged 26 or older, males, and minorities at highest risk.2 In addition, obese Soldiers (i.e., body mass index (BMI) greater than 30) were more likely to have medical and all-cause discharges from the U.S. Army during the first year of service compared to overweight or normal weight Soldiers.3 The duration of Active Duty service after overweight or obese diagnoses are shorter than non-overweight counterparts, with service members diagnosed with overweight or obesity leaving Active Duty service 9 and 18 months earlier, respectively, than matched controls.4 Furthermore, annual evaluations for United States Air Force Personnel includes a component that requires raters to “consider personal adherence and enforcement of fitness standards, dress and personal appearance, customs and courtesies, and professional conduct”.5 Thus, maintenance of weight within military standards not only affects the perception of a military service member’s competence, appearance, and ability to perform job functions, but has a concrete impact on promotions and retention. While there are clearly severe consequences of failed fitness tests (i.e. discharge from the military with the associated loss of pension and medical benefits), there are likely other factors that motivate healthy lifestyle practices among Military Personnel.

Motivation for weight loss is noted within the growing literature as a critical component of obesity treatment engagement and outcomes.6,7 Greater motivation reported early (i.e., 4 weeks) in an internet-based weight loss intervention with one initial motivation-based weight loss session predicted 5% weight loss at 16 weeks.8 However, the mere presence of motivation may not be indicative of weight loss success, rather specific motivation reasons for weight loss may predict success or lack of success. One study10 concluded that the “successful dieter” (i.e., a previously obese person who is currently at or below 27 body mass index and has maintained at least 20% weight loss for at least one year), reported motivators of attractiveness and health associated with maintenance of weight loss behaviors. The unsuccessful dieter (i.e., a currently obese individual) also had motivations of attractiveness and health, in addition to endorsing self-esteem issues and competition as motives.10 In addition, Kalarchian et al.9 found that it may be possible to increase weight loss success by tailoring the intervention to specific types of motivation. The authors concluded that the weight loss groups that emphasized appearance or health motivations had significantly greater weight loss than the standard intervention.9 Thus, reasons for initiating weight loss might differentially predict those who are successful and those who are not, and the reasons for initiating weight loss may differ by sociodemographic characteristics.

Numerous studies have found that both women 11–14 and men 14–18 consistently cite appearance and health concerns as reasons for entering a weight-loss program. Studies examining the motives of men show that improved fitness is particularly important16, 18 as well as becoming more effective in the workforce (i.e., increased productivity and fewer absences due to sickness), 17 reasons not typically noted in studies specific to the motives of women. Thus, the general consensus among the literature is that appearance and health are primary motivators for both men and women, with other specific motivators that may be more common in men or women.

While Striegel-Moore et al.12 found that African American and Caucasian women were similarly motivated by appearance, concerns with health, desiring to feel better about oneself, feeling uncomfortable physically, and wanting to have more energy, 12 other research has indicated racial differences in motivators for weight loss. In a survey of employees of various racial groups on the factors that influence attempts to lose weight, 19 having a chronic medical condition was a unique motivator for African American individuals, whereas a physician recommendation to lose weight was predictive of initiating weight loss attempts among Caucasian individuals. There were also racial differences in a study of participants who had similarly low socioeconomic status; Caucasian participants reported being motivated by feeling better, while the African American participants reportedly wanted to live longer.20 Thus, it appears that both African American and Caucasian individuals are motivated by appearance and health, there may be slight differences in other motivators by racial group.

Blixen, Singh, and Thacker11 found that there are not only differences in motivation about weight reduction among different racial groups, but also different age groups. Both focus groups of African American and Caucasian women in the sample (mean age of 42.8) attributed appearance as a motivation for attempted weight loss when they were younger and noted health reasons became the primary motivator as they aged. Consistent with those findings, Putterman and Linden14 found that younger dieters (mean age of 24.5) were more motivated by appearance relative to the older dieters (mean age of 38.9); older dieters were more likely to identify health concerns as their motivation in comparison to younger dieters. In a qualitative study, Clark13 found that health concerns were the primary reasons for weight loss by women in their seventies. The older women also indicated improvement in appearance as a motivator, but described it as a superficial concern and not a legitimate motivator. In a study of men, younger men (ages 18–29) attributed higher motivation of improved physical fitness, middle age men (ages 30–40) noted appearance as motivator, and the oldest men (ages 40–55) stated health concerns as a primary motivator.16 Thus, perhaps not surprisingly, there is emerging literature indicating that individuals of different age groups may be more driven by motivators that are more immediately relevant (e.g., individuals who are older and are more likely to have obesity-related health concerns, are more likely to cite health as a motivator).

This study investigates the motivational factors endorsed by Military Personnel initiating a behavioral weight loss study. Given the racial, ethnic, age, and gender diversity among Military Personnel, 21 this study will explore the nuances across these sociodemographic factors and investigate the added dimension of military service on weight loss motivation. The purpose of this study was to understand important motivational factors in Military Personnel that contribute to their initiation of a weight loss program. Since approximately half of all Military Personnel indicate they are trying to lose weight22, these findings may inform future weight loss intervention recruitment efforts or development of motivationally-focused intervention materials of military-specific weight loss programs.

Methodology

Participants

Active Duty Military Personnel (n=248), having at least one year on station at their current military installation, Joint Base San Antonio, Texas, were recruited to participate in this study. The service requirement was in place to maximize the likelihood that participants could attend in-person data collection at the 4- and 12- month follow up visits. Participant characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The majority of participants were in the Air Force (n=234), with 8 in the Navy, 4 in the Army and 2 in the Marines.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (N=248)

| Body Mass Index (BMI) (n (%)) | |

| Overweight (BMI<30 kg/m2) | 115 (46.4%) |

| Obese (BMI≥30 kg/m2) | 133(53.6%) |

| Age (n (%)) | |

| <30 years old | 66 (26.6%) |

| 30 to <40 years old | 123 (49.6%) |

| >40 years old | 59 (23.8%) |

| Gender (n (%)) | |

| Men | 122 (49.2%) |

| Women | 126 (50.8%) |

| Race (n (%)) | |

| African American/Black | 49 (19.8%) |

| Caucasian/White | 163 (65.7%) |

| Other (American Indian or Alaska Native, | 36 (14.5%) |

| Asian, and Native Hawaiian or Pacific | |

| Islanders, multiple race, and unknown race) | |

| Ethnicity (n (%)) | |

| Hispanic | 56 (22.6%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 192 (77.4%) |

| Military Rank (n (%)) | |

| E1–4 | 34 (13.8%) |

| E5–6 | 105 (42.5%) |

| E7–9 | 52 (21.0%) |

| O1–3 | 17 (6.9%) |

| O4–6 | 39 (15.8%) |

Eligibility for inclusion in the study included being at least 18 years old, BMI ≥ 25, and reliable phone and computer access. Participants also had to complete two tasks: 1) complete a week of daily dietary and physical activity self-monitoring using Lose It™ web application and 2) obtain a letter from their healthcare provider approving participation in the study. The exclusion criteria included having a medical condition (e.g., diabetes mellitus, disability inhibiting aerobic activity, recent pregnancy, uncontrolled cardiovascular abnormality, unstable psychiatric concern) that would impact their participation in the dietary changes and physical activity requirements of the study. Participants were also excluded if in the past 12 months, they had more than one failed attempt to pass the military-proctored physical fitness test; those participants had an increased likelihood of an imminent fitness- related military discharge, which would increase the likelihood of being unable to complete the study requirements. Participants were randomized to one of two intervention conditions via computerized block design: a counselor-initiated intervention or a self-paced intervention. Further details on study design are available elsewhere.23

Measures

Baseline weight was measured in kilograms on a calibrated scale. Participants were weighed without shoes in their physical training clothes or their uniform without their jacket. Baseline height was measured in centimeters using a wall-mounted stadiometer. BMI was then calculated using the standard formula. Analyses were evaluated based on demographic categories of gender, military ranking (i.e., 3 Enlisted (E) categories: E1-E4 (i.e., enlisted), E5-E6 (i.e., non-commissioned officers), E7-E9 (i.e., senior non-commissioned officers) and 2 Officer categories (O): O1-O3 (i.e., Company Grade Officer) and O4-O6 (i.e., Field Grade Officer), BMI (overweight: 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 and obese: ≥30 kg/m2), ethnicity (i.e., Hispanic or Non-Hispanic), and race (i.e., Caucasian, African American, or other). The racial category of “Other” consisted of American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, multiple race, and unknown race, combined in one group for statistical purposes given the infrequency of these responses.

Prior to initiating the weight loss interventions, weight loss motivations were assessed with a behavioral questionnaire, developed based on the factor structure of the Motivation for Weight Loss Scale24 and expectations of weight loss noted by Gorin et al.25 The questionnaire consists of 16 items. Participants were asked to indicate how important, if at all, each weight loss reason was in their decision to lose weight at this point in their lives. The responses were on a 5-point Likert scale (1- Very important to 5-Not at all important). For parsimony and clarity in reporting, the response categories were collapsed and dichotomized to “Very important” (i.e., responses 1) and “Not Very important” (i.e., responses 2–5).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were examined to determine the frequency of endorsement of the various motivation items. Chi-Square tests were used to assess if two categorical variables of interest are independent, and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare the distribution of a continuous variable across difference levels of a given factor.

Results

The participants were, on average, 34.6 ± 7.5 (mean ± SD) years old, with a large age range (i.e., 20–60 years of age). The mean BMI was 30.6 ± 2.7 (kg/m2 ± SD. There was a roughly equal proportion of men and women (Table 1). The sample was racially and ethnically diverse. Military rankings were varied from lowest ranking category of E1–4 to O4–6, with the highest proportion in the E5–6 category (40.3%). The four motivations for weight loss most frequently endorsed as “very important” by at least 75 percent of the overall sample were: improved physical health, improved fitness, improved quality of life, and to live long (Figure 1). ‘To pass the fitness test’ was endorsed less frequently as a “very important” motivation, by 69% of the sample. There were no significant differences between participants classified as overweight or obese across individual motivation items.

Figure 1.

The proportion of endorsement of motivations for weight loss items as “very important” by the full sample and across gender

There were numerous gender differences in motivations for weight loss (Figure 1), with women being significantly more likely to endorse all of the following motivations for weight loss as “very important” compared to men: improving mood/wellbeing (women: 76.2% vs. men: 52.5%, p<0.001), improving quality of life (women: 86.5% vs. men: 71.3%, p<0.01), improving physical mobility (women: 74.6% vs. men: 60.7%, p<0.05), improving job performance (women: 34.9% vs. men: 22.1%, p<0.05), improving appearance (women: 80.2% vs. men: 58.2%, p<0.05), improving sex life (men: 23.0% vs. women:34.9%, p<0.05), and fitting into clothes (women vs. men: 36.1%: 77.8%; p<0.001) (see Figure 1). A similar frequency of women and men endorsed being motivated to pass the military fitness test (women vs. men=64.8% men=64.8%: 74.6%; p=0.05).

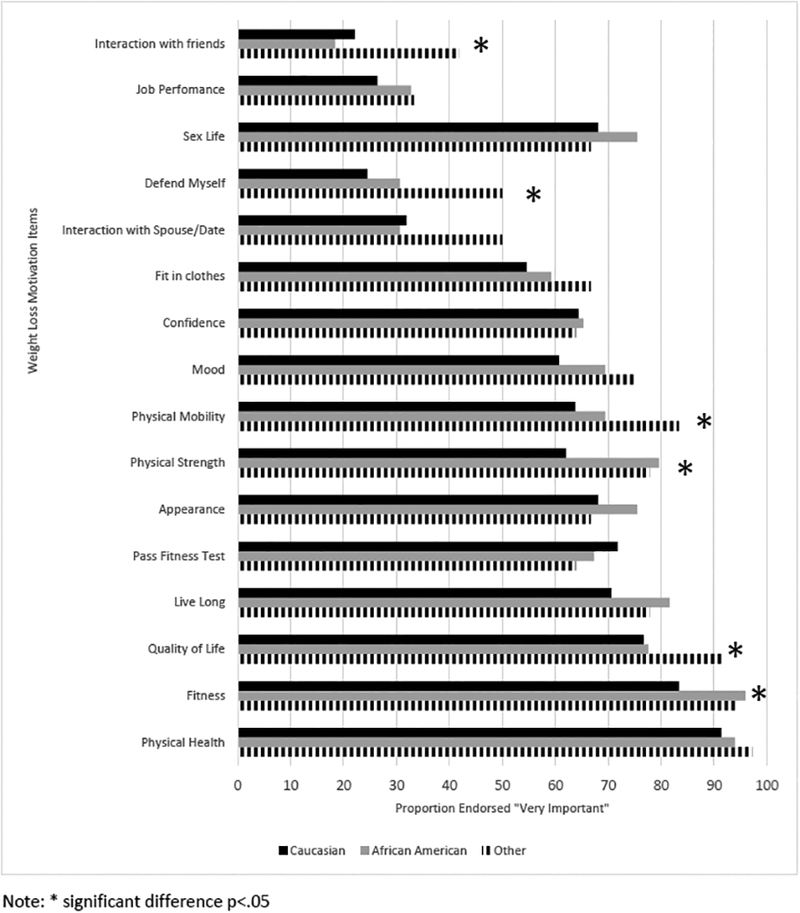

Several significant racial differences in endorsement of motivations for weight loss emerged (Figure 2). Specifically, participants who identified as African American or an “Other” race were more likely to rate improving fitness (African American: 95.9% vs. Other: 94.4% vs. Caucasian: 83.4%, p<0.01) and improving physical strength (African American: 79.6% vs. Other: 77.8% vs. Caucasian: 62.0%, p<0.05) as “very important” weight loss motivators compared to participants who identified as Caucasian. Those that classified in the “Other” race category were also significantly more likely to indicate that being able to physically defend oneself (Other: 50.0% vs. African American: 30.6% vs. Caucasian: 24.5%, p<0.01), improving their physical mobility (Other: 83.3% vs. African American: 69.4% vs. Caucasian: 63.8%, p<0.05) and improving interactions with friends (Other: 41.7 vs. African American: 18.4% vs. Caucasian: 22.1%, p<0.05) were “very important” weight loss motivators compared to participants who identified as African American or Caucasian.

Figure 2.

The proportion of endorsement of motivations for weight loss items as “very important” across racial groups

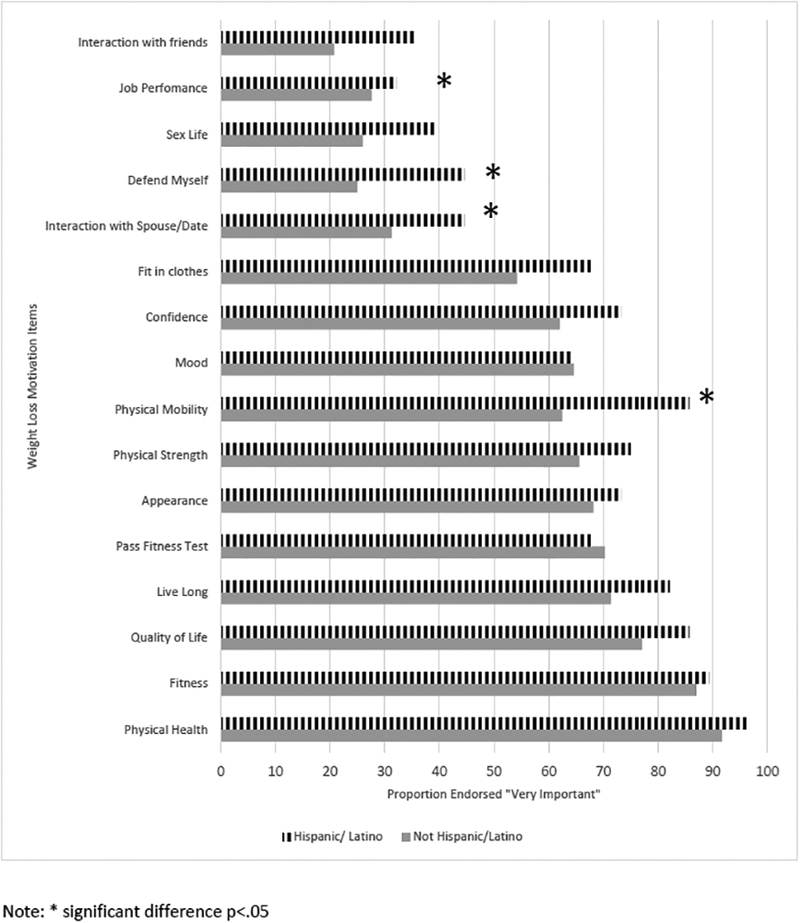

Endorsement patterns between Hispanic and non-Hispanic participants revealed some significant differences in motivations to lose weight (Figure 3). A significantly greater proportion of participants who identified as Hispanic endorsed being motivated by improving their ability to physically defend themselves (Hispanic: 44.6% vs. non-Hispanic 25.0%, p<0.01), improving interactions with friends (Hispanic: 35.7% vs. non-Hispanic: 20.8 %, p<0.01), improving physical mobility (Hispanic: 85.7% vs. non-Hispanic: 62.5%, p<0.01), and improving their sex life (Hispanic: 39.3% vs. non-Hispanic: 26.0%, p<0.05) compared to those who identified as non-Hispanic.

Figure 3.

The proportion of endorsement of motivations for weight loss items as “very important” by ethnicity

There were only two significant differences of motivation endorsement across the age groups: improving ability to physically defend oneself (Younger than 30: 42.4% vs. Between ages 30 and 40: 26.0% vs. Older than 40: 22.0%, p<0.05) and improving confidence (Younger than 30: 83.3% vs. Between ages 30 and 40: 61.8% vs. Older than 40: 49.2%, p<0.05), with the youngest age group being significantly more likely to endorse wanting to improve their ability to physically defend themselves and improve their confidence, compared to the two other age groups. We found just two significant differences by rank; specifically, a significantly greater percentage of officers of lower rank (i.e., O1–3) compared to the other categories endorsed being motivated to improve their quality of life (E1-E4: 91.2% vs. E5–6: 81.0% vs. E7–9: 82.7% vs. O1–3: 52.9% vs. O4–6: 69.1%, p<0.01), and a significantly greater proportion of lower ranking enlisted personnel (i.e., E1–4) reported wanting to lose weight to improve confidence compared to all of the other categories (E1-E4: 88.2% vs. E5–6: 63.8% vs. E7–9: 63.5% vs. O1–3: 52.9% vs. O4–6: 51.3%, p<0.05).

Discussion

Findings suggest that motivations for weight loss in this military population are largely consistent with the current literature of the general population; specifically improving physical health was a motivation for engaging in weight loss across all sociodemographic groups.14,19 Although many of the participants (69%) reported being very motivated to pass the fitness test, improving fitness in general, improving quality of life, and to live long were motivations endorsed as “very important” with greater frequency by the sample. It is also notable that appearance was rated as “very important” by 69.4 percent of the military population, a comparable frequency to that of passing the fitness test. Appearance is very important in the military, particularly uniform appearance; thus, as expected, a primary reason to lose weight was to look better. However, considering that appearance is also a component of the annual evaluation for Military Personnel,5 it was surprising that a greater proportion of the sample did not provide a high rating. Some might assume that given the consequences of a failed fitness test, passing one’s fitness test would be a unanimous motivator in the military; however, our results suggest that a broader range of reasons are motivations for weight loss among Active Duty personnel.

Motivations for weight loss in this military sample indicated the importance of physical health, improved fitness, and appearance (particularly for women), similar to motivations noted in the general population.12, 16 One notable difference from the general population, is that a significantly greater portion of women endorsed job performance as “very important” compared to men, whereas Sabinsky and colleagues17 noted job performance as a motivator for weight loss unique to men. This difference found in our military sample could be due to the fact that women are a minority in the military, 21 there may be increased concern of pressures with optimizing performance at work. There could also be concerns regarding pregnancy-related weight impacting perceived job performance, since most Active Duty women are of child bearing age. Women endorsed every motivation, with the exception of physical health, more frequently than men. Accordingly, women were more likely to endorse several weight loss motivations compared to men: improved physical mobility, improved mood, improved confidence, improved sex life, and to fit in clothes. It is unclear if women are endorsing the motivations with higher frequency than men because the choices do not adequately capture motivations important for men or if women genuinely feel stronger and more motivated thus consistently endorsing higher on the Likert scale.

For both those who identified as Hispanic and/or in the ‘Other’ race classification, improving the ability to defend oneself, improving interaction with friends, and increasing physical mobility are motivations for weight loss endorsed in greater frequency than for participants who identified as Caucasian and/or non-Hispanic. Considering that only 10% 26 of the Air Force self-identify as American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders, Multiracial, and 13 % identify as Hispanic, the small size of these groups may contribute to their concern with improving interpersonal interactions. The prevalence of perceived discriminatory practices based on minority status27–29 may contribute to these groups also being more vigilant to wanting to defend themselves as compared to Caucasians and Non-Hispanics. African Americans and those in the “Other” race category endorsed in significantly greater frequency than Caucasians being motivated by improving fitness and improving physical strength, possibly an indication of a greater focus on meeting or exceeding expectations for physical performance in an effort of combating possible bias as a consequence of negative stereotypes.30

Military rank is associated with age, yet rank also reflects professional achievement. For this reason, we examined both the impact of age and rank on endorsement of weight loss motivations. Lower ranking enlisted personnel and younger individuals consistently endorsed improving self-confidence as an important motivator, similar to civilian studies that note lower self-esteem at younger ages.31 Lower ranking officers were also motivated for weight loss in order to improve their quality of life; this is the first study of which we are aware which has examined weight loss motivations based on military rank and the finding remains to be replicated and contributing factors remain to be explored. Younger individuals also endorsed wanting to lose weight be able to physically defend themselves, possibly because younger individuals tend to engage in increased risk taking which would require greater concern with physically defending oneself.32

Perceived differences in weight classifications (for example, identifying as obese versus overweight, regardless of objective BMI), could impact motivations for engaging in weight loss because the person that identifies as obese might exhibit more motivation than a person that perceives themselves as overweight.33 However, we did not detect significant differences in motivations for weight loss between overweight and obese participants, perhaps because most obese participants in this sample would be classified as class 1 obese (i.e., BMI 30.0- <35.0 kg/m2), they may not perceive much difference in their health status or have dramatically different levels of weight concern from someone classified as overweight.

Strengths and Limitations

By recruiting a diverse group of Active Duty military service members representing both men and women, various racial groups, Hispanic and non-Hispanic participants, as well as a wide range in ages and military ranks, this study provides specific insight into the weight loss motivations for the Active Duty military as a whole. This in turn represents a significant population, with 1.3 million Active Duty personnel, more than half of whom are overweight or obese.1, 21 Another strength of the study is that it assesses for actual motivations for enrolling in a weight loss program, rather than assessing reasons to enroll in a hypothetical weight loss program.

Despite the many strengths of the study, there were limitations. The scale that assessed motivations was created based on Motivation for Weight Loss Scale24 and expectations of weight loss25; however, since these previous scales did not include military specific questions, they had to be adapted for the purposes of this study. The psychometric properties of this adapted scale are unknown. Since we did not generate the motivators for weight loss items using qualitative methods, it is possible that there are other important motivations for weight loss that are not captured in our results. Given that this study focused on motivations for initiating a behavioral weight loss program, there was not further assessment of motivations for weight loss or weight maintenance throughout the duration of the study. Future studies would benefit from follow-up measures to assess motivations that support the Military Personnel in maintaining engagement in the program. Finally, we did not assess career field, so we were unable to examine potential differences in weight loss motivations by support versus line career fields.

The results of this study may be beneficial in improving recruitment efforts for military-based weight loss interventions. The findings can inform researchers or clinicians to tailor recruitment materials to the most salient weight loss motivators (i.e., improved physical health, improved fitness, improved quality of life, and to live long) for the overall Active Duty military population or specific motivators for particular demographic groups.34–35 Future research should examine the impact of particular weight loss motivations on objective weight loss, which may help predict those individuals for whom weight loss programs will be most beneficial. Furthermore, the outcomes of the study may provide pertinent information for weight management interventions that include motivational factors (e.g., motivational interviewing-based interventions). It is also important to note that participants in the current sample endorsed motivations that are infrequently examined in the current literature (i.e. ability to physically defend oneself, increased mobility, and social interaction); future research should determine the relevance of these potential motivations among other populations.

Acknowledgments

The sponsor did not have a role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The research represents a Collaborative Research and Development Agreement with the United States Air Force (CRADA #13-168- SG-C13001). The opinions expressed in this document are solely those of the authors and do not represent an endorsement by or the views of the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Ann Hryshko-Mullen for her invaluable assistance in the conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Military Medicine following peer review. The version of record, Maclin-Akinyemi C, Krukowski RA, Kocak M, Talcott GW, Beauvais A, & Klesges RC. (2017). Motivations for Weight Loss Amongst Active Duty Military Personnel. Military Medicine, 182(9), e1816-e1823, is available online at: https://academic.oup.com/milmed/article-abstract/182/9-10/e1816/4627036 or https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00380

References

- 1.Barlas FM, Higgins WB, Pflieger JC, Diecker K. 2011. Health related behaviors survey of active duty military personnel. ICF International Inc. 2013www.murray.senate.gov/.../final-2011-hrb-active-duty-survey-report.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reyes-Guzman CM, Bray RM, Forman-Hoffman VL, Williams J. Overweight and obesity trends among active duty military personnel. Am J Prev Med 2015;48(2):145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Packnett ER, Niebuhr DW, Bedno SA, Cowan DN. Body mass index, medical qualification status, and discharge during the first year of US Army service. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;93(3):608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Defense. Monthly Surveillance Monthly Report. Duration of service after overweight-related diagnoses, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 1998–2010. 2011;18(6):2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers PW. Interim Air Force guidance memorandum for AFI 10–248, fitness program Department of the Air Force. Mil Med 1978;143(9):613–618. doi: 10.1016/0265-9646(86)90023-8.AFI36-2406, 20135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, North American Association for the Study of Obesity: Practical guide to the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. Washington DC: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/prctgd_c.pdf. Published October 2000. Accessed October 10, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silva MN, Markland D, Carraça EV, et al. Exercise autonomous motivation predicts 3-yr weight loss in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43(4):728–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webber KH, Tate DF, Ward DS, Bowling JM. Motivation and its relationship to adherence to self-monitoring and weight loss in a 16-week internet behavioral weight loss intervention. J Nutr Educ Behav 2010;42(3):161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, Klem ML, Burke LE, Soulakova JN, Marcus MD. Impact of addressing reasons for weight loss on behavioral weight-control outcome. Am J Prev Med 2011;40(1):18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brink PJ, Ferguson K. The Decision to Lose Weight. WESTERN J NURS RES 1998; 20(1):84–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blixen CE, Singh A, Thacker H. Values and beliefs about obesity and weight reduction among African American and Caucasian women. J Transcult Nurs 2006;17(3):290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Striegel-Moore RH, Wilfley DE, Caldwell MB, Needham ML, Brownell KD. Weight-related attitudes and behaviors of women who diet to lose weight: A comparison of Black dieters and White dieters. Obes Res 1996;4(2):109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke LH. Older women’s perceptions of ideal body weights: The tensions between. Ageing Soc 2002;22 751–773. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Putterman E, Linden W. Appearance versus health: does the reason for dieting affect dieting behavior? J Behav Med 2004;27(2):185–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Souza PD. Men and dieting: A qualitative analysis. J. Health Psychol 2005;10(6):793–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hankey CR, Leslie WS, Lean MEJ. Why lose weight? Reasons for seeking weight loss by overweight but otherwise healthy men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26(6):880–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabinsky MS, Toft U, Raben A, Holm L. Overweight men’s motivations and perceived barriers towards weight loss. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007;61(4):526–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfe BL, Smith JE. Different Strokes for Different Folks : Weight loss treatment. Eat Disord 2002;10(2):115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zapka J, Lemon SC, Estabrook B, Rosal MC. Factors related to weight loss behavior in a multiracial/ethnic workforce. Ethn Dis 2009;19(2):154–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eikenberry N, Smith C. Healthful eating: perceptions, motivations, barriers, and promoters in low-income Minnesota communities. J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104(7):1158–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Defense. 2011. Health related behaviors survey of active duty military personnel. http://health.mil/Reference-Center/Reports/2013/02/01/2011-Health-Related-Behaviors-Active-Duty-Executive-Summary. Published February 2013. Accessed October 10, 2016

- 22.Department of Defense. 2005. Department of Defense survey of health related behaviors among Active Duty Military Personnel. http://www.dtic.mil/get-tr-doc/pdf?AD=ADA465678. Accessed January 10, 2017.

- 23.Krukowski RA, Hare ME, Talcott GW, et al. Dissemination of the Look AHEAD intensive lifestyle intervention in the United States Air Force: Study rationale, design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials 2015;40:232–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer AH, Weissen-Schelling S, Munsch S, Margraf J. Initial development and reliability of a motivation for weight loss scale. Obes Facts 2010;3(3):7–7. doi: 10.1159/000315048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorin AA, Pinto AM, Tate DF, Raynor HA, Fava JL, Wing RR. Failure to meet weight loss expectations does not impact maintenance in successful weight losers. Obesity 2007; 15(12):3086–3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Air Force Personnel Center - Air Force Personnel Demographics. Air Force Personnel Center - Air Force Personnel Demographics. http://www.afpc.af.mil/library/airforcepersonneldemographics.asp. Published March 31, 2016. Accessed July 19, 2016.

- 27.Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, Alegría M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. J Community Psychol 2008;36(4):421–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puhl RM, Andreyeva T, Brownell KD. Perceptions of weight discrimination: prevalence and comparison to race and gender discrimination in America. Int J Obes 2008;32(6):992–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. Am J Public Health 2003;93(2):200–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biernat M, Crandall CS, Young LV, Kobrynowicz D, Halpin SM. All that you can be: Stereotyping of self and others in a military context. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;75(2):301–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens C, Tiggemann M. Women’s body figure preferences across the life span. The J Genet Psychol 1998;159(1):94–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyer T The development of risk-taking: A multi-perspective review. Dev Rev 2006;26(3):291–345. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yaemsiri S, Slining MM, Agarwal SK. Perceived weight status, overweight diagnosis, and weight control among US adults: the NHANES 2003–2008 Study. Int J Obes 2010;35(8):1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher TL, Burnet DL, Huang ES, Chin MH, Cagney KA. Cultural Leverage: interventions using culture to narrow racial disparities in health care. Med Care Res Rev 2007;64(5 suppl): 243–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz DC, Clark EM, Sanders-Thompson V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: Targeted and tailored Approaches. Health Educ Behav 2003;30(2):133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]