Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that impairs a patient’s memory and other important mental functions. In this paper, we leverage the mutually informative and complementary features from both structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) for improving the diagnosis. Due to the feature redundancy and sample outliers, direct use of all training data may lead to suboptimal performance in classification. In addition, as redundant features are involved, the most discriminative feature subset may not be identified in a single step, as commonly done in most existing feature selection approaches. Therefore, we formulate a hierarchical multimodal feature and sample selection framework to gradually select informative features and discard ambiguous samples in multiple steps. To positively guide the data manifold preservation, we utilize both labeled and unlabeled data in the learning process, making our method semi-supervised. The finally selected features and samples are then used to train support vector machine (SVM) based classification models. Our method is evaluated on 702 subjects from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) dataset, and the superior classification results in AD related diagnosis demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach as compared to other methods.

1 Introduction

As one of the most common neurodegenerative diseases, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) accounts for most dementia cases. AD is progressive and the symptoms worsen over time by gradually affecting patients’ memory and other mental functions. Unfortunately, there is no cure for AD yet. Nevertheless, once AD is diagnosed, treatment including medications and management strategies can help improve symptoms. Therefore, timely and accurate diagnosis of AD and its prodromal stage, i.e., mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which can be further categorized into progressive MCI (pMCI) and stable MCI (sMCI), is highly desired in practice. Among various diagnosis tools, brain imaging, such as structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), has been widely used, since it allows accurate measurements of the brain structures, especially in the hippocampus and other AD related regions [1].

Besides imaging data, genetic variants are also related to AD [2], and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been conducted to identify the association between single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and the imaging data [3]. In [4], the associations between SNPs and MRI-derived measures with the presence of AD were explored and the informative SNPs were identified to guide the disease interpretation. To date, most of the previous works focused on analyzing the correlation between imaging and genetic data [5], while using both for AD/MCI diagnosis has received very little attention [6]. In this paper, we aim to jointly use structural MRI and SNPs for improving AD/MCI diagnosis, as the data from both modalities are mutually informative [3].

For MRI-based diagnosis, features can be extracted from regions-of-interest (ROIs) in the brain [6]. Since not all of the ROIs are relevant to the particular disease of AD/MCI, feature selection can be conducted to identify the most relevant features in order to learn the classification model more effectively [7]. Similarly, only a small number of SNPs from a large SNP pool are associated with AD/MCI [6]. Therefore, it is preferable to use only the most discriminative features from both MRI and SNPs to learn the most effective classification model. To achieve this, supervised feature selection methods such as Lasso-based sparse feature learning have been widely used [8]. However, they do not consider discarding non-discriminative samples, which might be outliers or non-representative, and including them in the model learning process can be counterproductive.

In this paper, we propose a semi-supervised hierarchical multimodal feature and sample selection (ss-HMFSS) framework. We utilize both labeled and unlabeled data for manifold regularization, to preserve the neighborhood structures during the mapping from the original feature space to the label space. Furthermore, since the redundant features and outlier samples inevitably affect the learning process, instead of selecting features and samples in one step, we perform feature and sample selection in a hierarchical manner. The updated features and pruned sample set from each current hierarchy are supplied to the next one to further identify a subset with most discriminative features and samples. In this way, we gradually refine the feature and sample subsets step-by-step, undermining the effect of non-discriminative or rather noisy data. The finally selected features and samples are used to train support vector machine (SVM) classifiers for AD and MCI related diagnosis. The proposed method is evaluated on 702 subjects from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort. In different classification tasks, i.e., AD vs. NC, MCI vs. NC, and pMCI vs. sMCI, superior results are achieved by our framework as compared to the other competing methods.

2 Method

2.1 Data Preprocessing

In this study, we use 702 subjects in total from the ADNI cohort whose MRI and SNP features are available1. Among them, 165 are AD patients, 342 are MCI patients, and the rest 195 subjects are normal controls (NCs). Within the MCI patients, there are 149 pMCI cases and 193 sMCI cases. sMCI subjects are those who were diagnosed as MCI patients and remained stable all the time, while pMCI refers to the MCI case that converted to AD within 24 months.

For MRI data, the preprocessing steps included skull stripping, dura and cerebellum removal, intensity correction, tissue segmentation and registration. The preprocessed images were then divided into 93 pre-defined ROIs, and the gray matter volume in these ROIs are calculated as MRI features. The SNP data were genotyped using the Human 610-Quad BeadChip. According to the AlzGene database2, only SNPs that belong to the top AD gene candidates were selected. The selected SNPs were imputed to estimate the missing genotypes, and the Illumina annotation information was used to select a subset of SNPs [9]. The processed SNP data have 2098 features. Since the SNP feature dimension is much higher than that of MRI, we perform sparse feature learning [8] on the training data to reduce the SNP feature dimension to the similar level of the MRI feature dimension.

2.2 Semi-supervised Hierarchical Feature and Sample Selection

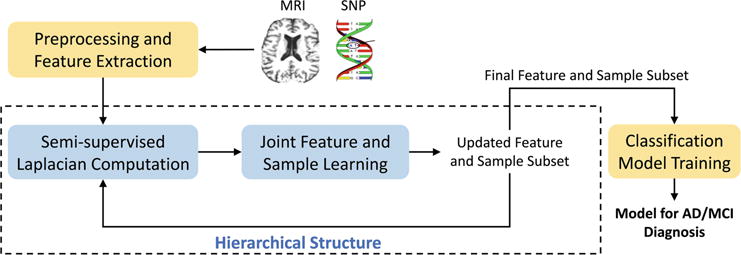

The framework of the proposed method is illustrated in Fig. 1. After features are extracted and preprocessed from the raw SNP and MRI data, we first calculate the graph Laplacian matrix to model the data structure using the concatenated features from both labeled and unlabeled data. This Laplacian matrix is then used in the manifold regularization to jointly learn the feature coefficients and sample weights. The features are selected and weighted based on the learned coefficients, and the samples are pruned by discarding those with smaller sample weights. The updated features and samples are forwarded to the next hierarchy for further selection in the same manner. In such a hierarchical manner, we gradually select the most discriminative features and samples in order to mitigate the effects of data redundancy in the learning process. Finally, the selected features and samples are used to train classification models (SVM in this work) for AD/MCI diagnosis tasks. In the following, we explain in detail how the joint feature and sample selection works in each hierarchy.

Fig. 1.

Framework of the proposed semi-supervised hierarchical multimodal feature and sample selection (ss-HMFSS) for AD/MCI diagnosis.

Suppose we have N1 labeled training subjects with their class labels and the corresponding features from both MRI and SNP, denoted by , , and , respectively. In addition, data from N2 unlabeled subjects are also available, denoted as , and . The goal is to utilize both labeled and unlabeled data in a semi-supervised framework to jointly select the most discriminative samples and features for the subsequent classification model training and prediction. Let be the concatenated features of the labeled data, represent features of the unlabeled data, and be the feature coefficient vector, the objective function for this joint sample and feature learning model can be written as

| (1) |

where is the loss function defined for the labeled data, and is the manifold regularization term for both labeled and unlabeled data. This regularizer is based on the natural assumption that if two data samples xp and xq are close in their original feature space, after mapping into the new space (i.e., label space), they should also be close to each other. is the sparse regularizer for the purpose of feature selection. In the following, we explain in detail how the loss function and the manifold regularization term are defined by taking into account sample weights.

Loss function

The loss function considers the weighted loss for each sample, and it is defined as

| (2) |

where is a diagonal matrix with each diagonal element denoting the weight for a data sample. Intuitively, a sample that can be more accurately mapped into the label space with less error is more desirable, and thus it should contribute more to the classification model. The sample weights in A will be learned through optimization and the samples with larger weights will be selected to train the classifier.

Manifold regularization

The manifold regularization preserves the neighborhood structures for both labeled and unlabeled data during mapping from the feature space to the label space. It is defined as

| (3) |

where contains features of both labeled data X and unlabeled data . The Laplacian matrix is given by L = D − S, where D is a diagonal matrix such that D(p, p) = Σq S(p, q), and S is the affinity matrix with S(p, q) denoting the similarity between samples xp and xq. S(p, q) is defined as

| (4) |

where yp and yq are the labels for xp and xq. For the case of unlabeled data, yp defines a soft label for an unlabeled data sample xp as , where is the number of xp’s neighbors with positive class labels out of its k neighbors in total. Note that for an unlabeled sample, the nearest neighbors are searched only in the labeled training data, and the soft label represents its closeness to a target class. Using such definition, the similarity matrix S encodes relationships among both labeled and unlabeled samples.

The diagonal matrix applies weights on both labeled and unlabeled samples. The elements in  are different for labeled and unlabeled data:

| (5) |

By this definition, if an unlabeled sample whose k nearest neighbors are relatively balanced from both positive and negative classes (i.e., ), it is assigned a smaller weight as this sample may not be representative enough in terms of class separation. The weights in A for the labeled data are to be learned in the optimization process.

Overall objective function

Taking into account the loss function, the manifold regularization, as well as the sparse regularization on features, the objective function is

| (6) |

Note that the elements in A are enforced to be non-negative to assign physically interpretable weights to different samples. Also, the diagonal of A should sum to one, which makes the sample weights to be interpreted as probabilities, and also ensures that sample weights will not be all zero. We employ an alternating optimization strategy to solve this problem, i.e., we fix A to find the solution of w, and vice versa. For solving w, the Accelerated Proximal Gradient (APG) algorithm is used. The optimization on A is a constrained quadratic programming problem and it can be solved using the interior-point algorithm. After this hierarchy, insignificant features and samples are discarded based on the values in w and A, and the remaining features are weighted by the coefficients in w. The remaining samples with their updated features are used in the next hierarchy to further refine the sample and feature set. The entire process of the proposed method is summarized in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1.

Semi-supervised hierarchical multimodal feature and sample selection

| Input: | |

| Labeled and unlabeled data from MRI and SNP, and the number of hierarchies L. | |

| 1: | Initialize labeled sample weights in A and feature coefficients in w. |

| 2: | for i = 1 to L do |

| 3: | Calculate the data similarity scores in S by Eq. (4). |

| 4: | Calculate the sample weights in  by Eq. (5). |

| 5: | repeat |

| 6: | Fix A and solve w in Eq. (6). |

| 7: | Fix w and solve A in Eq. (6). |

| 8: | until convergence |

| 9: | Discard insignificant samples and features based on the values in A and w. |

| 10: | Weight the remaining features by the coefficients in w. |

| 11: | end for |

| Output: | |

| Subset of samples and features for classification model training. | |

3 Experiments

Experimental Settings

We consider three binary classification tasks in the experiments: AD vs. NC, MCI vs. NC, and pMCI vs. sMCI. A 10-fold cross-validation strategy is adopted to evaluate the classification performance. For the unlabeled data used in our method, we choose the irrelevant subjects with respect to the current classification task, i.e., when we classify AD and NC, the data from MCI subjects are used as unlabeled data. The dimension of the SNP features is reduced to 100 before the joint feature and sample learning. The neighborhood size k is chosen by cross-validation on the training data. After each hierarchy, 5 % samples are discarded, and the features whose coefficients are smaller than 10−3 are removed. To train the classifier, we use LIBSVM’s implementation of linear SVM3. The parameters in feature and sample selection for each classification task are determined by grid search on the training data.

Results

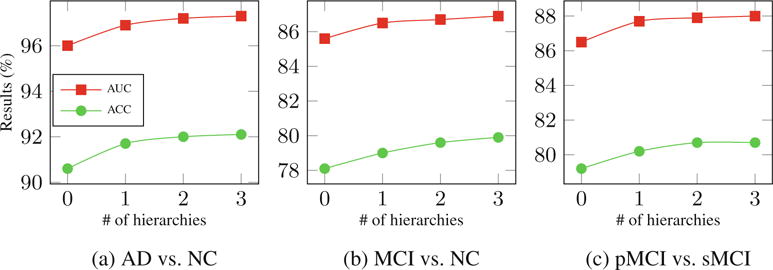

To examine the effectiveness of the proposed hierarchical structure, Fig. 2 shows classification accuracy (ACC) and area under receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) with different number of hierarchies. It is observed that the use of more hierarchies benefits the classification performance in all tasks, although the improvement becomes marginal after the third hierarchy. Especially for cases such as pMCI vs. sMCI, where the training data are not abundant, keeping discarding samples and features in many hierarchies may result in insufficient classification model training. Therefore, we set the number of hierarchies to three in our experiments. It is also worth mentioning that compared to AD vs. NC classification, MCI vs. NC and pMCI vs. sMCI classifications are more difficult, yet they are important problems for early diagnosis and possible therapeutic interventions.

Fig. 2.

Effects of using different numbers of hierarchies.

For benchmark comparison, the proposed method (ss-HMFSS) is compared with the following baseline methods: (1) classification using MRI features only without feature selection (noFS (MRI only)), (2) classification using SNP features only without feature selection (noFS (SNP only)), (3) classification using concatenated MRI and SNP features without feature selection (noFS), (4) classification using concatenated MRI and SNP features with Laplacian score for feature selection (Laplacian), and (5) classification using concatenated MRI and SNP features with Lasso-based sparse feature learning (SFL). In addition, we evaluate the performance of our method using labeled data only (HMFSS). Besides, we also report sensitivity (SEN) and specificity (SPE).

The mean classification results are reported in Table 1. Regarding each feature modality, MRI is more discriminative than SNP to distinguish AD from NC, while for MCI vs. NC and pMCI vs. NC classifications, SNP is more useful. Directly combining features from two different modalities may not necessarily improve the results. For example, in AD vs. NC classification, simply concatenating SNP and MRI features decreases the accuracy due to the less discriminative nature of the SNP features, which negatively contribute in the classification model learning. This limitation is alleviated by SFL. In our method, we further improve the selection scheme in a hierarchical manner and only the most discriminative features and samples are kept to train the classification models. Even without using unlabeled data, our method (i.e., HMFSS) outperforms the other baseline methods. By incorporating unlabeled data to facilitate the learning process, the performance of our method (i.e., ss-HMFSS) is further improved. It is also worthwhile to mention that when only feature example is enabled in our method, the accuracies for the three classification tasks are 91.1 %, 77.2 %, and 77.9 %, respectively, which are all inferior to the results using both feature and sample selection. Compared with a state-of-the-art method for AD diagnosis [10], which considers the relationships among samples and different feature modalities when performing feature selection, at least a 1–2% improvement in accuracy is achieved by our method on the same data. Regarding the computational cost, our method in Matlab implementation on a computer with 2.4 GHz CPU and 8 GB memory takes about 15 s for feature and sample selection, and the SVM classifier training takes less than 0.5 s.

Table 1.

Comparison of classification performance by different methods (in %)

| Method | AD vs. NC | MCI vs. NC | pMCI vs. sMCI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC | SPE | SEN | AUC | ACC | SPE | SEN | AUC | ACC | SPE | SEN | AUC | |

| noFS (MRI only) | 88.3 | 81.9 | 92.2 | 94.1 | 72.5 | 80.7 | 42.9 | 72.0 | 68.4 | 59.4 | 75.9 | 73.2 |

| noFS (SNP only) | 77.3 | 75.3 | 80.6 | 85.3 | 74.8 | 83.2 | 36.1 | 74.1 | 73.1 | 67.7 | 80.8 | 79.2 |

| noFS | 87.5 | 81.6 | 90.3 | 95.6 | 73.8 | 85.1 | 53.6 | 80.6 | 74.7 | 64.5 | 78.8 | 83.4 |

| Laplacian | 88.7 | 82.9 | 90.5 | 95.7 | 74.6 | 86.9 | 56.8 | 82.8 | 75.5 | 67.3 | 81.4 | 77.5 |

| SFL | 89.2 | 83.6 | 90.7 | 95.8 | 74.7 | 87.3 | 57.6 | 83.2 | 76.3 | 68.1 | 83.0 | 77.9 |

| HMFSS | 90.8 | 83.9 | 94.1 | 96.7 | 77.6 | 83.9 | 65.7 | 85.2 | 78.3 | 68.9 | 84.5 | 85.6 |

| ss-HMFSS | 92.1 | 85.7 | 95.9 | 97.3 | 79.9 | 85.0 | 67.5 | 86.9 | 80.7 | 71.1 | 85.3 | 88.0 |

4 Conclusions

In this paper, we have proposed a semi-supervised hierarchical multimodal feature and sample selection (ss-HMFSS) framework for AD/MCI diagnosis using both imaging and genetic data. In addition, both labeled and available unlabeled data were utilized to preserve the data manifold in the label space. Experimental results on the data from ADNI cohort showed that the hierarchical scheme was able to gradually refine the feature and sample set in multiple steps. Superior performance in different classification tasks was achieved as compared to the other baseline methods. Currently, data from two modalities including MRI and SNP were used. We would like to extend our method to utilize data from more modalities, such as positron emission tomography (PET) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), to further improve the diagnosis performance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants (EB006733, EB008374, EB009634, MH100217, MH108914, AG041721, AG049371, AG042599).

Footnotes

References

- 1.Chen G, Ward BD, Xie C, Li W, Wu Z, Jones JL, Franczak M, Antuono P, Li SJ. Classification of Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, and normal cognitive status with large-scale network analysis based on resting-state functional MR imaging. Radiology. 2011;259(1):213–221. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaiteri C, Mostafavi S, Honey CJ, De Jager PL, Bennett DA. Genetic variants in Alzheimer disease - molecular and brain network approaches. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:1–15. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen L, Kim S, Risacher SL, Nho K, Swaminathan S, West JD, Foroud T, Pankratz N, Moore JH, Sloan CD, Huentelman MJ, Craig DW, DeChairo BM, Potkin SG, Jack CR, Jr, Weiner MW, Saykin AJ. Whole genome association study of brain-wide imaging phenotypes for identifying quantitative trait loci in MCI and AD: a study of the ADNI cohort. NeuroImage. 2010;53(3):1051–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hao X, Yu J, Zhang D. Identifying genetic associations with MRI-derived measures via tree-guided sparse learning. In: Golland P, Hata N, Barillot C, Hornegger J, Howe R, editors. MICCAI 2014 LNCS. Vol. 8674. Springer; Heidelberg: 2014. pp. 757–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin D, Cao H, Calhoun VD, Wang YP. Sparse models for correlative and integrative analysis of imaging and genetic data. J Neurosci Methods. 2014;237:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Z, Huang H, Shen D. Integrative analysis of multi-dimensional imaging genomics data for Alzheimer’s disease prediction. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:260. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu X, Suk HI, Lee SW, Shen D. Canonical feature selection for joint regression and multi-class identification in Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015;10:818–828. doi: 10.1007/s11682-015-9430-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye J, Farnum M, Yang E, Verbeeck R, Lobanov V, Raghavan N, Novak G, DiBernardo A, Narayan VA. Sparse learning and stability selection for predicting MCI to AD conversion using baseline ADNI data. BMC Neurol. 2012;12(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertram L, McQueen MB, Mullin K, Blacker D, Tanzi RE. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat Genet. 2007;39:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu M, Zhang D, Shen D. Relationship induced multi-template learning for diagnosis of Alzheimers disease and mild cognitive impairment. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2016;35(6):1463–1474. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2016.2515021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]