Abstract

This study was designed to evaluate the combined effects of bacteriophage and antibiotic on the reduction of the development of antibiotic-resistance in Salmonella typhimurium LT2. The susceptibilities of S. typhimurium to ciprofloxacin and erythromycin were increased when treated with bacteriophages, showing more than 10% increase in clear zone sizes and greater than twofold decrease in minimum inhibitory concentration values. The growth of S. typhimurium was effectively inhibited by the combination of bacteriophage P22 and ciprofloxacin. The combination treatment effectively reduced the development of antibiotic resistance in S. typhimurium. The relative expression levels of efflux pump-related genes (acrA, acrB, and tolC) and outer membrane-related genes (ompC, ompD, and ompF) were decreased at all treatments. This study provides useful information for designing new antibiotic therapy to control antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Keywords: Bacteriophage, Salmonella, Antibiotic, Ciprofloxacin, Disk diffusion assay

Introduction

Non-typhoidal Salmonella typhimurium and S. Enteritidis, are the most common pathogenic serovars that can cause gastroenteritis, enteric fever, infectious diarrheal, and septicemia [1]. Non-typhoidal Salmonella infections remain a serious public health problem worldwide, which resulted in approximately 94 million cases and 155,000 deaths annually [2]. Furthermore, non-typhoidal Salmonella serovars represent a reservoir of antibiotic resistance determinants [16]. This is responsible for the acquisition of multiple antibiotic resistance to β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, and tetracycline in non-typhoidal Salmonella serovars [7, 15]. The mechanisms of antibiotic resistance include enzymatic degradation of antibiotics, activation in efflux pump systems, and alteration in membrane permeability [8, 17]. The emergence and dissemination of antibiotic-resistant Salmonella have become a major problem in a clinical and hospital setting due to the frequent failure in antibiotic treatments [25]. Therefore, the novel approach to improving current antibiotic use is essential for control of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

Recently, bacteriophage has been renewed attention as an alternative approach for treatment of bacterial infections due to its effective specificity to target bacteria [3]. Bacteriophages can recognize the bacterial cell surface-exposed receptors such as pili, flagella, capsule, membrane proteins, and lipopolysaccharides [26, 31]. Recent studies have reported the effectiveness of using bacteriophages in combating against bacterial pathogens, including bacteriophage cocktails and bacteriophage-antibiotic combinations [9, 23, 29, 30]. Most researches highlights that the application of bacteriophages can be a promising strategy to overcoming antibiotic resistance. However, relatively few studies have evaluated the bacteriophage resistance mechanisms when bacteria are exposed to selective pressure. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the efficiency of bacteriophage-antibiotic combination against S. typhimurium and also evaluate bacterial resistance to bacteriophage.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

Strain of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar typhimurium LT2 (ATCC 19585) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in trypticase soy broth (TSB) (BD, Becton, Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD, USA) at 37 °C for 20 h. The cultured cells were centrifuged at 3000×g for 20 min at 4 °C. The collected cells diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) to 108 CFU/ml.

Bacteriophage propagation and enumeration

Salmonella bacteriophage P22 (ATCC 97541) was propagated at 37 °C for 24 h in TSB containing S. typhimurium as a suggested host. The propagated phages were harvested by centrifugation at 5000×g for 10 min. The harvested phages were filtered through a 0.2-μm filter to eliminate bacterial lysates. The phage titers were determined by using the double agar overlay plaque assay [4]. In brief, phages were diluted with PBS. The diluted phages were mixed with TSB (0.5% agar) containing the host cells (107 CFU/ml) and then poured onto the agar lawn plates. The soft-agar overlaid plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to count the phages which were expressed as plaque-forming unit (PFU).

Agar diffusion test

The disk diffusion susceptibility was measured to determine the synergistic effect of phage P22 and antibiotic. The Muller–Hinton agar plates containing S. typhimurium (105 CFU/ml) were prepared without and with phage P22 (105 PFU/ml). The antibiotic disks, including cefotaxime (30 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), erythromycin (15 μg), streptomycin (10 μg), and tetracycline (30 μg), were placed on the prepared Muller–Hinton agar plates and then incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. After incubation, the diameters of the zone of inhibition were measured in centimeters using a digital vernier caliper (The L.S. Starrett Co., Athol, MA, USA).

Preparation of antibiotic stock solutions

All antibiotics used in this study were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). The stock solutions of cefotaxime in water, chloramphenicol in absolute ethanol, ciprofloxacin in glacial acetic acid, erythromycin in absolute ethanol, streptomycin in water, and tetracycline in absolute ethanol were prepared at a concentration of 1024 mg/ml. The antibiotic working solutions were freshly prepared prior to use.

Antibiotic susceptibility assay

The susceptibility of S. typhimurium to each antibiotic was evaluated in the absence and presence of phage P22. S. typhimurium (105 CFU/ml) was inoculated in 96-well microtiter plates containing twofold serial dilution of each antibiotic (cefotaxime, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, streptomycin, or tetracycline) without and with phage P22. The inoculated 96-well plates were incubated for 18 h at 37 °C. The growth of S. typhimurium was observed at 600 nm [13] and fitted to exponential function using Microcal Origin® 8.0 (Microcal Software Inc., Northampton, MA, USA).

Time-kill curve analysis

The inhibitory effects of phage P22, ciprofloxacin, and combination against S. typhimurium was evaluated by the time-kill assay. Phage P22 (105 PFU/mL), ciprofloxacin (1 × MIC; 0.016 μg/mL), and combination were inoculated with S. typhimurium (105 CFU/mL) in TSB. Each treatment was cultured for 20 h at 37 °C. The growth of S. typhimurium was measured at every 4-h interval. After 20-h culture, samples were collected for the analyses of antibiotic resistance and gene expression.

Antibiotic resistance profile

The changes in antibiotic resistance phenotype after the time-kill assay were estimated by using a disk diffusion assay. S. typhimurium cells cultured in the control, phage P22 alone, ciprofloxacin alone, and combination were streaked onto Muller–Hinton agar plate. The antibiotic disks (cefotaxime, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, streptomycin, and tetracycline) were placed on the prepared Muller–Hinton agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. After incubation, the antibiotic susceptibility was compared by measuring the diameters of clear zone.

Quantitative PCR assay

Total RNA from S. typhimurium cells cultured in the control, phage P22 alone, ciprofloxacin alone, and combination was extracted according to the protocol of RNeasy Protect Bacteria Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and then cDNA was synthesized according to the QuantiTech reverse transcription procedure (Qiagen). For qPCR assay, the reaction mixture (10 μl of 2 × QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master, 2 μl of each primer (Table 1), 2 μl of cDNA, and 4 μl of RNase-free water) was amplified using an iCycler iQ™ system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hemel Hempstead, UK). The mixture was denatured at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 55 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 15 s. The comparative method [14] was used to evaluate the relative gene expression in S. typhimurium cells cultured in phage P22 alone, ciprofloxacin alone, and combination.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used in qPCR analysis for S. typhimurium

| Gene | Molecular function | Primer sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | Reference gene | F: AGGCCTTCGGGTTGTAAAGT R: GTTAGCCGGTGCTTCTTCTG |

| acrA | Multidrug efflux system | F: AAAACGGCAAAGCGAAGGT R: GTACCGGACTGCGGGAATT |

| acrB | Multidrug efflux system | F: TGAAAAAAATGGAACCGTTCTTC R: CGAACGGCGTGGTGTCA |

| ompC | Outer membrane protein C | F: TCGCAGCCTGCTGAACCAGAAC R: ACGGGTTGCGTTATAGGTCTGAG |

| ompD | Outer membrane protein D | F: GCAACCGTACTGAAAGCCAGGG R: GCCAAAGAAGTCAGTGTTACGGT |

| ompF | Outer membrane protein F | F: AGTGGGTTCAATCGATTATG R: GAATATATTTCGCCAGATCG |

| tolC | Multidrug efflux system | F: GCCCGTGCGCAATATGAT R: CCGCGTTATCCAGGTTGTTG |

aF forward, R reverse

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in duplicate for three replicates. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Analysis System software. The general linear model and Fisher’s least significant difference procedures were used to determine significant mean differences at P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of S. typhimurium in the presence of phages

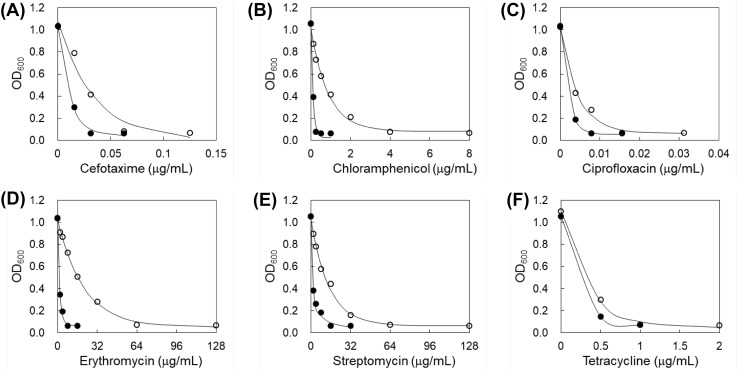

The antibiotic susceptibility of S. typhimurium LT2 was evaluated in the absence and presence of phage P22 using disk diffusion assay (Table 2). The clear zone sizes of cefotaxime, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, streptomycin, and tetracycline disks were increased to 13, 10, 22, 25, 9, and 12%, respectively, in the presence of phage P22. The growth of phages was stimulated by antibiotics [6], leading to the enhanced lysis of host bacterium, S. typhimurium LT2. This result is a good agreement with previous report that the increased plaque size and phage titer were observed after antibiotic treatment [10]. The MIC values of antibiotics against S. typhimurium LT2 were evaluated in the absence of presence of phage P22 (Fig. 1). The antibiotic susceptibilities of LT2 were noticeably increased in the presence of phage P22 compared to the absence of phage P22, showing more than twofold decrease in MIC values; cefotaxime (0.06–0.03 μg/mL), chloramphenicol (4–0.25 μg/mL), ciprofloxacin (0.016–0.008 μg/mL), erythromycin (64–8 μg/mL), streptomycin (64–16 μg/mL), and tetracycline (2–1 μg/mL). The decreased MIC values in S. typhimurium LT2 treated with combination might be due to the changes in permeability and efflux pump activity [18]. Antibiotics play an important role in the increased burst size and reduced latent period of phages, leading to an increase in the susceptibility of bacteria [29]. However, antibiotics can interfere with the phage replication within bacteria cells, resulting in the reduction in the phage-antibiotic combination effect [5]. Therefore, further studies are needed to understand the mechanisms of phage-host interplay and antibiotic resistance for phage-antibiotic-based therapeutic approach.

Table 2.

Antibiotic disk diffusion (cm) of S. typhimurium in the absence and presence of phages

| Antibiotic | S. typhimurium | |

|---|---|---|

| No phage | Phage | |

| Cefotaxime | 3.61 ± 0.111aA | 4.08 ± 0.14aA |

| Chloramphenicol | 2.85 ± 0.07bA | 3.12 ± 0.09bA |

| Ciprofloxacin | 3.54 ± 0.08aA | 4.32 ± 0.12aB |

| Erythromycin | 1.27 ± 0.06eA | 1.58 ± 0.06dB |

| Streptomycin | 1.59 ± 0.06dA | 1.73 ± 0.08dA |

| Tetracycline | 2.14 ± 0.07cA | 2.39 ± 0.11cA |

1Means with different letters (a–e) within a column are significantly different at P < 0.05 and means with different letters (A–B) within a row are significantly different at P < 0.05

Fig. 1.

Antibiotic susceptibility of S. typhimurium in the absence (opened circle) and presence (filled circle) of bacteriophages

Combined inhibitory effect of phage and ciprofloxacin on the growth of S. typhimurium

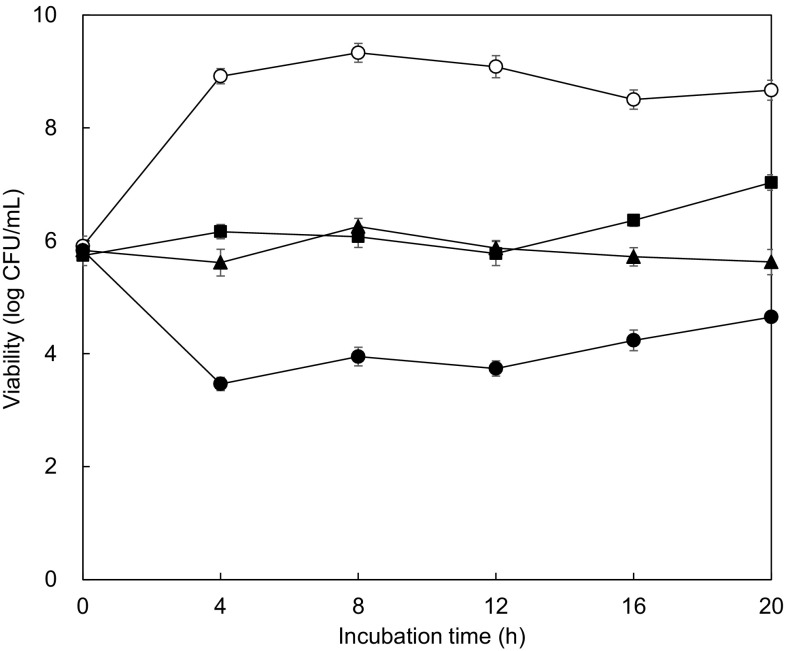

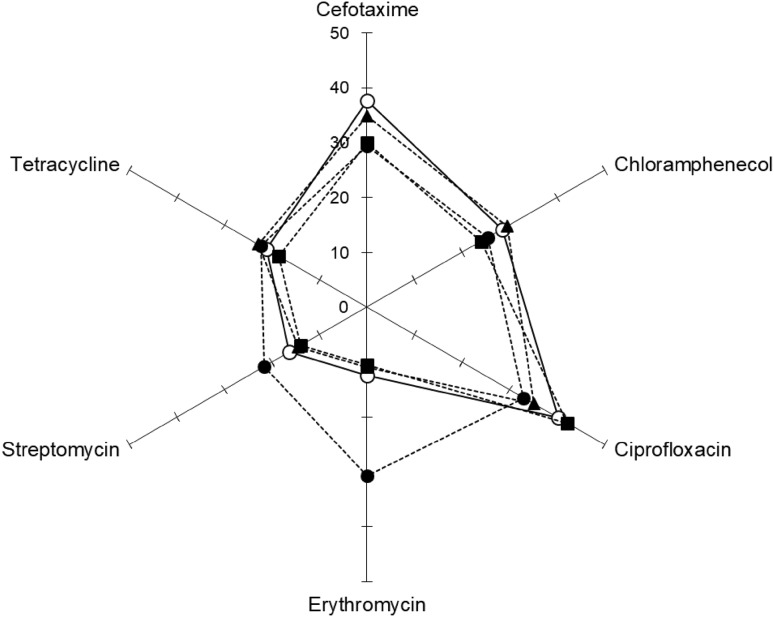

The antimicrobial effect of phage P22 alone, ciprofloxacin alone, and combination against S. typhimurium LT2 was evaluated at 37 °C for 20 h (Fig. 2). Ciprofloxacin was used to evaluate the induction of antibiotic resistance, representing the second generation of fluoroquinolone. Compared to the control, the growth of S. typhimurium LT2 was significantly inhibited by all treatments throughout the incubation. The most considerable reduction was observed for the combination treatment, resulting in more than 5-log reduction up to 12-h of incubation. However, the number of S. typhimurium LT2 treated with phage P22 was increased after 12-h incubation. This might be due to the presence of bacterial cells resistant to bacteriophage P22 [12]. The ability of develop resistance to antibiotics was evaluated in S. typhimurium LT2 treated with phage P22, ciprofloxacin, and combination after 20-h incubation (Fig. 3). The antibiotic susceptibilities varied in the treatments. Compared to the control, the enhanced susceptibilities of S. typhimurium LT2 to erythromycin, streptomycin, and tetracycline were observed at the combination treatment, while S. typhimurium LT2 treated with phage P22 alone and antibiotic alone was less sensitive to erythromycin and streptomycin. The results suggest that appropriate antibiotic use can improve the antimicrobial activity when combined with phages. The phage-antibiotic combination can be possibly used to reduce the resistance to phages and antibiotics [19, 22].

Fig. 2.

Survival of S. typhimurium incubated with none (control; opened circle), bacteriophage alone (filled square), ciprofloxacin alone (filled triangle), and combination of bacteriophage and ciprofloxacin (filled circle) at 37 °C for 20 h

Fig. 3.

Radar plot of antibiotic resistance profiles (disk diffusion in cm) of S. typhimurium incubated with none (control; opened circle), phage P22 alone (filled square), ciprofloxacin alone (filled triangle), and combination of phage P22 and ciprofloxacin (filled circle) at 37 °C for 20 h. Antibiotic disks include cefotaxime (30 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), erythromycin (15 μg), streptomycin (10 μg), and tetracycline (30 μg)

Differential gene expression of S. typhimurium treated with phage, ciprofloxacin, and combination

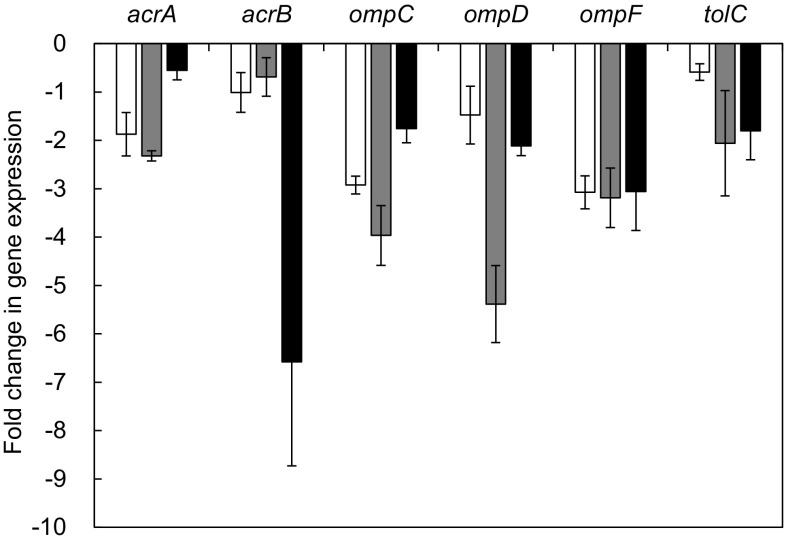

The relative expression of efflux pump-related genes (acrA, acrB, and tolC) and outer membrane-related genes (ompC, ompD, and ompF) was observed in S. typhimurium LT2 treated with phage P22 alone, antibiotic alone, and combination, compared to the control (Fig. 4). The relative expression levels of genes used in this study were decreased at all treatments. The antibiotic resistance in bacteria is associated with the efflux pump systems, including ATP-binding cassette (ABC), major facilitator (MF), small multidrug resistance (SMR), multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE), and resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) [20]. The tripartite efflux transporter complex, AcrAB-TolC, is mainly responsible for the antibiotic resistance in S. typhimurium, which has a broad specificity to various substrates such as β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, tetracycline, and erythromycin [11, 27]. In structure, AcrA, AcrB, and TolC are located in the periplasmic protein, the inner membrane, and the outer membrane, respectively [21]. The downregulation of efflux pump-related genes (acrA, acrB, and tolC) and outer membrane-related genes (ompC, ompD, and ompF) are responsible for the reduced permeability and efflux of antibiotics, leading to the increase in the antibiotic susceptibility of S. typhimurium LT2 [18, 24, 28]. Moreover, the decrease in AcrAB–TolC leads to reduce the virulence of Salmonella because acrA, acrB, and tolC are required for efficient adhesion invasion of epithelial cells and macrophages [32]. Phage combined with antibiotic, known as phage-antibiotic synergy (PAS), can be an alternative way to control bacterial infections. PAS can also be a possible strategy for reducing the emergence of phage-resistant mutants [22].

Fig. 4.

Relative gene expression S. typhimurium LT2 treated with phage P22 alone (opened square), ciprofloxacin alone (filled square), and combination of phage P22 and ciprofloxacin (filled square) at 37 °C for 20 h

In conclusion, the significant findings are that the antibiotic susceptibility of S. typhimurium LT2 was significantly increased when combined with phages and the growth of S. typhimurium LT2 was synergistically inhibited by the combination of phage P22 and antibiotic. The combined treatment of phage P22 and ciprofloxacin could downregulate the expression of efflux pump-related genes (acrA, acrB, and tolC) and outer membrane-related genes (ompC, ompD, and ompF), resulting in the increased antibiotic susceptibility of S. typhimurium LT2. These results highlight the advantages of using phage-antibiotic combination to prevent the emergence of antibiotic resistant strains.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016R1D1A3B01008304). This study was supported by a Research Grant from Kangwon National University (2017) (Grant number: D1001438-01-01). This study was also supported by funding from the graduate school of Prince of Songkla University.

References

- 1.Acheson D, Hohmann EL. Nontyphoidal Salmonellosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;32:263–269. doi: 10.1086/318457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ao TT, Feasey NA, Gordon MA, Keddy KH, Angulo FJ, Crump JA. Global burden of invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:941–949. doi: 10.3201/eid2106.140999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardina C, Spricigo DA, Cortes P, Llagostera M. Significance of the bacteriophage treatment schedule in reducing Salmonella colonization of poultry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:6600–6607. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01257-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bielke L, Higgins S, Donoghue A, Donoghue D, Hargis BM. Salmonella host range of bacteriophages that infect multiple genera. Poul. Sci. 2007;86:2536–2540. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhry WN, Concepción-Acevedo J, Park T, Andleeb S, Bull JJ, Levin BR. Synergy and order effects of antibiotics and phages in killing Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0168615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comeau AM, Tétart F, Trojet SN, Prère M-F, Krisch HM. Phage-antibiotic synergy (PAS): β-Lactam and quinolone antibiotics stimulate virulent phage growth. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahshan H, Shahada F, Chuma T, Moriki H, Okamoto K. Genetic analysis of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovars Stanley and Typhimurium from cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;145:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giedraitienė A, Vitkauskienė A, Naginienė R, Pavilonis A. Antibiotic resistance mechanisms of clinically important bacteria. Medicina. 2011;47:137–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jo A, Ding T, Ahn J. Synergistic antimicrobial activity of bacteriophages and antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016;25:935–940. doi: 10.1007/s10068-016-0153-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamal F, Dennis JJ. Burkholderia cepacia complex phage-antibiotic synergy (PAS): Antibiotics stimulate lytic phage activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:1132–1138. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02850-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi N, Tamura N, van Veen HW, Yamaguchi A, Murakami S. β-Lactam selectivity of multidrug transporters AcrB and AcrD resides in the proximal binding pocket. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:10680–10690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.547794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;8:317–327. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin H-L, Lin C-C, Lin Y-J, Lin H-C, Shih C-M, Chen C-R, Huang R-N, Kuo T-C. Revisiting with a relative-density calibration approach the determination of growth rates of microorganisms by use of optical density data from liquid cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:1683–1685. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00824-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−∆∆CT Method. Method. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mather AE, Reid SW, Maskell DJ, Parkhill J, Fookes MC, Harris SR, Brown DJ, Coia JE, Mulvey MR, Gilmour MW, Petrovska L, de Pinna E, Kuroda M, Akiba M, Izumiya H, Connor TR, Suchard MA, Lemey P, Mellor DJ, Haydon DT, Thomson NR. Distinguishable epidemics of multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium DT104 in different hosts. Science. 2013;341:1514–1517. doi: 10.1126/science.1240578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michael GB, Schwarz S. Antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic nontyphoidal Salmonella; an alarming trend? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016;22:968–974. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miró E, Vergés C, García I, Mirelis B, Navarro F, Coll P, Prats G, Martínez-Martínez L. Resistance to quinolones and β-lactams in Salmonella enterica due to mutations in topoisomerase-encoding genes, altered cell permeability and expression of an active efflux system. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2015;33:204–211. doi: 10.1016/s0213-005x(04)73067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moya-Torres A, Mulvey MR, Kumar A, Oresnik IJ, Brassinga AKC. The lack of OmpF, but not OmpC, contributes to increased antibiotic resistance in Serratia marcescens. Microbiol. 2014;160:1882–1892. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.081166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muniesa M, Colomer-Lluch M, Jofre J. Potential impact of environmental bacteriophages in spreading antibiotic resistance genes. Future Microbiol. 2013;8:739–751. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikaido E, Yamaguchi A, Nishino K. AcrAB multidrug efflux pump regulation in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by RamA in response to environmental signals. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:24245–24253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804544200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikaido H, Basina M, Nguyen V, Rosenberg EY. Multidrug efflux pump AcrAB of Salmonella typhimurium excretes only those beta-lactam antibiotics containing lipophilic side chains. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:4686–4692. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4686-4692.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oechslin F, Piccardi P, Mancini S, Gabard J, Moreillon P, Entenza JM, Resch G, Que Y-A. Synergistic interaction between phage therapy and antibiotics clears Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in endocarditis and reduces virulence. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;215:703–712. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perera MN, Abuladze T, Li M, Woolston J, Sulakvelidze A. Bacteriophage cocktail significantly reduces or eliminates Listeria monocytogenes contamination on lettuce, apples, cheese, smoked salmon and frozen foods. Food Microbiol. 2015;52:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piddock LV. Understanding the basis of antibiotic resistance: a platform for drug discovery. Microbiol. 2014;160:2366–2373. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.082412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prestinaci F, Pezzotti P, Pantosti A. Antimicrobial resistance: a global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2015;109:309–318. doi: 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rakhuba DV, Kolomiets EI, Dey ES, Novik GI. Bacteriophage receptors, mechanisms of phage adsorption and penetration into host cell. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2010;59:145–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ricci V, Piddock LJ. Only for substrate antibiotics are a functional AcrAB-TolC efflux pump and RamA required to select multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009;64:654–657. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rushdy AA, Mabrouk MI. Abu-Sefa FA-H, Kheiralla ZH, -All SMA, Saleh NM. Contribution of different mechanisms to the resistance to fluoroquinolones in clinical isolates of Salmonella enterica. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;17:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan EM, Alkawareek MY, Donnelly RF, Gilmore BF. Synergistic phage-antibiotic combinations for the control of Escherichia coli biofilms in vitro. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012;65:395–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spricigo DA, Bardina C, Cortés P, Llagostera M. Use of a bacteriophage cocktail to control Salmonella in food and the food industry. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013;165:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stecher B, Hapfelmeier S, Müller C, Kremer M, Stallmach T, Hardt W-D. Flagella and chemotaxis are required for efficient induction of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium colitis in streptomycin-pretreated mice. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:4138–4150. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4138-4150.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webber MA, Piddock LJV. The importance of efflux pumps in bacterial antibiotic resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003;51:9–11. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]