Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the oils of soybean (S), papaya (Pa) and melon (Me) seeds and compounds oils SPa (80:20 w/w); SMe (80:20 w/w); and SPaMe (60:20:20 w/w/w) subjected to thermoxidation. Compound oils showed lower percentages of free fatty acids in relation to others, after 20 h. With the heating process, there was an increase in the quantity of saturated and monounsaturated acids. The quantity of carotenoids decreased, except in papaya seed oil that presented significant amount of carotenoids in 20 h. In relation the tocopherols, highlighted the presence of γ-tocopherol, except in the papaya oil. In 20 h, SMe and SPa still showed high amounts of tocopherols, with 76 and 85% of retention, respectively. With the thermoxidation, the amounts of phytosterols decreased. A great potential can be verified for the use of papaya and melon seed oils, in order to increase the oxidative stability of the soybean oil.

Keywords: Seeds, Special oils, Physicochemical properties, Bioactive compounds, Antioxidant activity

Introduction

Papaya and melon fruits are consumed in natura or in their processed forms as jams, sweets, pulps, yogurts, and ice creams. In the processing fruits, peels and seeds, which compose about 50% of the fruit, are discarded. Papaya and melon seeds present in its constitution, compounds with antioxidant action, among which stand out carotenoids, phenolic compounds, tocopherols and phytosterols [1]. Thus, the seeds can be used as food products or as raw material for the extraction of oils, with high nutritional value [2].

Vegetable oils which are destined human consumption are obtained only one type of raw material. These oils receive more specific applications, for instance, in sauces or in food frying usages. However, most vegetable oils, as soybean oil, present a limited utilization in their original form, as a consequence of their chemical composition and physical characteristics; in spite of having, an excellent nutritional profile, these oils present, a high content of polyunsaturated fatty acids which makes the use of this oil impossible in high temperatures, due to the formation of compounds that are harmful to health [3]. These compounds originating from oxidation can interfere with the absorption of protein and folic acid by the body. Also represent risks to the intestinal mucosa, cause pathological changes, inhibit the activity of several enzymes, increase cholesterol and blood peroxides, and interact with DNA [4].

Thus, with the search for healthier foods, especially of the vegetable type, and the need of vegetable oils with higher antioxidant capacity, the so called “compound oils” appeared [5]. These oils, which have a special composition, represent 15% of the total Brazilian consumption of vegetable oils. Compound oils are obtained from mixtures of oils of two or more vegetable species [6].

The investigation of compound oils, especially the ones originating from non conventional oils, is an emerging research field which is not very well explored yet. In this context, since papaya and melon seed oils contain important bioactive compounds, these oils may be used with other vegetable oils in order to enrich them nutritionally. The objective of this study was to evalue to effect of papaya and melon seed oils on the soybean oil stability submitted under thermoxidation conditions. These two seeds were chosen for the extraction of oils, due to the agroindustrial residues of juice and sweet processing industries. Moreover, they are oils which have high stability and large amounts of bioactive compounds.

Materials and methods

Raw materials

Seeds of papaya (Carica papaya L.) of variety Formosa (cultivar formosa papaya) and of melon (Cucumis melo L.) of variety Inodorus (cultivar yellow) were used. The seeds of formosa papaya were granted by the DeMarchi company (Jundiaí, São Paulo, Brazil), and came from Bahia State. The yellow melon seeds were obtained from fruits purchased at the State Supply Center from São José do Rio Preto-SP, but from the Brazilian Northeast. 10 kg of fruit seeds harvested from September to August of the 2013/2014 season were removed. Finally, the seeds were air dried in a forced circulation oven at 40 ± 0.5 °C for 48 h and stored in glass jars.

Preparation of oils

The extraction process described was performed in the Institute of Food Technology-ITAL (Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil). For oils extraction, 10 kg of papaya and melon seeds were laminated in mini press (MPE 40, Ecirtec, Bauru, São Paulo, Brazil). The laminated seeds were put in an expeller equipment and the extraction by solvent was performed in four stages. In each stage, 20 L of hexane were used at 45–50 °C. At first the hexane flowed for 20 min; in the second and third ones, flowed for 15 min, then, in the last one, only for 10 min. After extraction, the solvent was removed with the application of direct and indirect steam. The oils percentages extracted from papaya (Pa) and melon (Me) seeds were 11.7 and 15.3%, respectively.

Besides these oils, refined soybean oil (S) no addition of synthetic antioxidant was granted by the company Triângulo Alimentos® located at Itápolis, São Paulo, Brazil, for the formulation of compounds oils: Soybeans and papaya (SPa, 80:20 w/w); Soybeans and melon (SMe, 80:20 w/w) and Soybeans, papaya and melon (SPaMe, 60:20:20 w/w/w). The soybean oil was used due to be widely consumed in Brazil.

Thermoxidation

The oils were subjected to thermoxidation in heating plates, and such experiment was performed discontinuously (10 h of heating/day) in heated plates at 180 ± 5 °C. Samples were taken at time periods of 0, 5, 10, 15 and 20 h, stored in amber glass flasks, inertized with nitrogen and conditioned to a temperature of − 18 °C until the moment of analysis.

Physicochemical properties

The analyses of free fatty acid, peroxide value, conjugates dienoic acids, ρ-anisidine were performed according to AOCS procedures [7] The polar compounds were performed through analyzer Testo 265, and total amount of oxidation (Totox) was calculated using the equation: Totox = 2 (peroxide value) + (ρ-anisidine). The oxidative stability was performed using the Rancimat at 110 °C, with air flow of 20 L/h.

The fatty acid composition was conducted through chromatography from the esterified oils through the method which was described by Hartman and Lago [8]. A gas chromatograph (model 3900, Varian, Walnut Creek, CA, USA) with a flame ionization detector, split injection system, and fused-silica capillary column was used (CP-Sil 88, Microsorb, Varian, Walnut Creek, CA, USA). The column oven temperature was initially held at 90 °C (10 min), heated at 10 °C/min at 195 °C and maintained at 195 °C/16 min. The injector and detector temperatures were 230 and 250 °C, respectively. Samples (1 μL) were injected adopting a split ratio of 1:30. The carrier gas was hydrogen with a flow rate of 30 mL/min. Fatty acids methyl esters (FAMEs) were identified by comparing their retention times with those of pure FAME standards (Supelco, Bellefonte, USA) under the same operating conditions. The integration software computed the peak areas and percentages of fatty acid methyl esters were obtained as weight percentage by direct internal normalization.

Total carotenoids were performed in a scanning spectrophotometer (Model UV–VIS mini 1240. Shimadzu, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan), in a 300–550 nm wavelength range, using the value A of 2592, in petroleum ether, expressed as micrograms β-carotene equivalents, in per gram of oil (µg/g), according to the methodology described by Rodriguez-Amaya [9].

In order to determine total phenolic compounds, the quantitative analyses were performed spectrophotometrically (Model UV–VIS mini 1240. Shimadzu, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan), using the Folin–Ciocalteau reagent and gallic acid standard curve, as the method described by Singleton and Rossi [10]. The results were expressed as mg GAE/kg.

The tocopherols analysis was performed according to AOCS procedures [7] in high performance liquid chromatograph (model 210-263, Varian Inc., Walnut Creek, CA, USA) with fluorescence detector, stainless steel column packed with silica (microsorb Si 100, Varian Inc., Walnut Creek, CA, USA) and wavelength excitation in 290 nm and emission at 330 nm. The quantification of each isomer was performed by external standardization based on peak areas, using standards of α-, β-, γ- e δ-tocopherol (Supelco, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, USA), whose results were expressed as milligram per kilogram of oil (mg/kg).

The phytosterols were determined by chromatography from the unsaponifiable matter. Saponification was performed according to the method published by Duchateau et al. [11]. To chromatographic analysis, it was used a gas chromatograph (Model 2010 Plus-Shimadzu, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan). The temperatures used in the injector and detector were 280 and 320 °C respectively. The carrier gas was hydrogen. Phytosterols were identified accordingly with the retention times, comparing with standards of purity of 95–98% (Supelco, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, USA) and analyzed under the same conditions of the samples. The quantification of each of the isomers was instead by internal standardization (cholestan-5α-3β-ol), based on the peak areas, and expressed in mg/100 g.

Antioxidant capacity

Antioxidant capacity analysis was performed through four different methodologies. They were all conducted in a spectrophotometer (model UV–VIS mini 1240, Shimadzu, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan). DPPH˙ analysis was performed as per Kalantzakis et al. [12]. That method consists of evaluating the sequestering activity of free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl. Then, the methodology described by Re et al. [13] was performed, it is based on the capacity for molecular antioxidants to reduce ABTS radical +, and its result is expressed in µM trolox/100 g. Antioxidant activity analysis was also conducted through FRAP method, which is based on the ability for phenols to reduce complex Fe+3-TPTZ (tripyridyl-s-Triazine ferric iron) to complex Fe+2-TPTZ (tripyridyl-s-Triazine ferrous iron) at pH 3.6. That methodology was described by Szydlowska-Czerniak et al. [14]. and expressed as µM trolox/100 g. Besides that, the analysis of β-carotene/linoleic acid was conducted according to the method that was modified by Miller [15], which assesses the inhibition capacity of free radicals that are generated during the peroxidation of linoleic acid. The absorbance was measured at 470 nm, and the results were expressed as percentages.

Statistical analysis

The experiment was performed at an entirely random delineation in factorial scheme. The results obtained from the analytical determinations, in triplicate, were subjected to variance analysis and the differences between means were tested at 5% probability by the Tukey test, using the ESTAT program, version 2.0.

Results and discussion

Physicochemical properties

The thermoxidation process aims at submitting oils and fats to elevated temperatures (180 °C), similarly to the frying process, but without the presence of food [7]. In the soybean oil was not detected free fatty acids, because it is refined oil. It was found that SPa, SMe and SPaMe compound oils showed lower percentages of free fatty acids in relation to papaya and melon oils (Table 1). The SPa and SMe oils also showed constant value under increased heating time. Thus, these oils can be considered oils of lower hydrolytic degradation.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the oils in thermoxidation

| Oils | Time (h) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | ||

| Free fatty acids (%) | S | ndbF | ndbE | ndbF | ndbF | 0.2 ± 0.0aE |

| Pa | 5.5 ± 0.4bA | 5.9 ± 0.1aA | 4.9 ± 0.0dA | 5.2 ± 0.0cA | 5.6 ± 0.0bA | |

| Me | 1.4 ± 0.1cB | 2.0 ± 0.0bB | 1.3 ± 0.0cB | 2.8 ± 0.0aB | 1.9 ± 0.1bB | |

| SPa | 0.7 ± 0.0aD | 0.6 ± 0.0aD | 0.5 ± 0.0aD | 0.6 ± 0.0aD | 0.7 ± 0.0aD | |

| SMe | 0.2 ± 0.0aE | 0.4 ± 0.0aD | 0.3 ± 0.0aE | 0.4 ± 0.0aE | 0.4 ± 0.0aE | |

| SPaMe | 1.1 ± 0.1aC | 0.9 ± 0.0abC | 0.8 ± 0.0bC | 0.9 ± 0.0abC | 1.1 ± 0.0aC | |

| Peroxides (meq O2/kg) | S | 3.2 ± 0.1dA | 2.4 ± 0.0eA | 4.2 ± 0.0cA | 5.2 ± 0.0aA | 4.4 ± 0.0bA |

| Pa | ndaE | ndaD | ndaF | ndaE | ndaF | |

| Me | 1.2 ± 0.0bC | 1.3 ± 0.1bB | 1.4 ± 0.0aD | 1.4 ± 0.0aB | 1.3 ± 0.0bB | |

| SPa | 1.3 ± 0.0bC | 0.8 ± 0.0dC | 1.6 ± 0.1aC | 0.8 ± 0.0dD | 0.9 ± 0.1cD | |

| SMe | 2.7 ± 0.0aB | 0.8 ± 0.0eC | 2.1 ± 0.0bB | 0.9 ± 0.0dC | 1.1 ± 0.0cC | |

| SPaMe | 1.0 ± 0.0aD | 0.8 ± 0.0bC | 0.8 ± 0.0bE | 0.8 ± 0.0bD | 0.8 ± 0.0bE | |

| Conjugated dienoic acids (%) | S | 0.4 ± 0.0eD | 0.7 ± 0.0dC | 1.6 ± 0.01cA | 1.9 ± 0.01bA | 2.8 ± 0.02aA |

| Pa | 0.2 ± 0.0eE | 0.6 ± 0.0dF | 0.8 ± 0.01cF | 0.8 ± 0.01bF | 1.0 ± 0.0aD | |

| Me | 0.9 ± 0.0eA | 1.0 ± 0.0dA | 1.2 ± 0.01cB | 1.6 ± 0.02aB | 1.2 ± 0.0bB | |

| SPa | 0.4 ± 0.0eD | 0.6 ± 0.0dE | 0.8 ± 0.01cE | 0.8 ± 0.0bE | 1.1 ± 0.0aC | |

| SMe | 0.5 ± 0.0eB | 0.7 ± 0.0dD | 0.9 ± 0.0bC | 0.9 ± 0.01cD | 1.0 ± 0.0aE | |

| SPaMe | 0.5 ± 0.0eC | 0.8 ± 0.0 dB | 0.9 ± 0.0cD | 0.9 ± 0.0bC | 1.2 ± 0.0aB | |

| Polar compounds (%) | S | 10.5 | 12.0 | 18.5 | 23.5 | 29.0 |

| Pa | 16.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 17.5 | 18.0 | |

| Me | 15.0 | 16.0 | 16.0 | 18.0 | 18.5 | |

| SPa | 11.5 | 11.5 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 13.5 | |

| SMe | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 14.0 | |

| SPaMe | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 13.5 | 14.5 | |

| ρ-anisidine | S | 3.9 ± 0.1dA | 43.4 ± 0.6cA | 54.2 ± 0.7aA | 49.9 ± 3.2bA | 51.7 ± 0.0bA |

| Pa | 1.4 ± 0.1cBC | 4.2 ± 0.2bE | 2.1 ± 0.0cF | 7.3 ± 0.5aE | 4.9 ± 0.5bF | |

| Me | 0.9 ± 0.0dBC | 13.2 ± 0.4bD | 15.5 ± 0.2aE | 11.4 ± 2.2bcD | 9.9 ± 0.0cD | |

| SPa | 2.8 ± 0.0cB | 15.7 ± 0.2bC | 25.5 ± 0.4aC | 25.1 ± 0.6aB | 15.7 ± 0.2bC | |

| SMe | 2.6 ± 0.0eAB | 23.1 ± 0.3cB | 31.2 ± 1.3aB | 26.2 ± 0.3bB | 20.4 ± 0.4 dB | |

| SPaMe | 0.7 ± 0.0dE | 15.3 ± 0.7bC | 18.2 ± 0.2aD | 17.4 ± 0.2aC | 7.0 ± 0.4cE | |

| Totox | S | 10.2 ± 0,2dA | 48.1 ± 0.6cA | 62.6 ± 0.8aA | 60.2 ± 3.3bA | 60.5 ± 0.1bA |

| Pa | 1.4 ± 0.1cD | 4.2 ± 0.2bD | 2.1 ± 0.0cE | 7.3 ± 0.5aE | 4.9 ± 0.5bF | |

| Me | 3.3 ± 0.1dD | 15.8 ± 0.5bC | 18.3 ± 0.3aD | 14.1 ± 2.2bcD 2.17dBC | 12.5 ± 0.0cD | |

| SPa | 5.4 ± 0.2dC | 17.2 ± 0.2cC | 28.6 ± 0.5aC | 26.7 ± 0.5bB | 17.5 ± 0.3cC | |

| SMe | 7.9 ± 0.1eB | 24.7 ± 0.3cB | 35.3 ± 1.4aB | 28.1 ± 0.3bB | 22.6 ± 0.4 dB | |

| SPaMe | 2.8 ± 0.0dD | 16.9 ± 0.7bC | 19.8 ± 0.2aD | 19.1 ± 0.2aC | 8.6 ± 0.4cE | |

| Oxidative stability (h) | S | 6.7 ± 0.4aE | 6.7 ± 0.4aB | 3.9 ± 0.3bC | 3.7 ± 0.3bcC | 3.2 ± 0.1cC |

| Pa | 17.3 ± 0.5aA | ndbE | ndbD | ndbE | ndbE | |

| Me | 13.7 ± 0.4aB | 1.9 ± 0.0cdD | 4.0 ± 0.1bC | 1.4 ± 0.1dD | 2.0 ± 0.2cD | |

| SPa | 9.3 ± 0.1bCD | 9.5 ± 0.3bA | 7.8 ± 0.1dA | 8.7 ± 0.1cA | 10.4 ± 0.2aA | |

| SMe | 8.8 ± 0.3aD | 5.5 ± 0.1dC | 7.3 ± 0.2bAB | 5.7 ± 0.1cdB | 6.0 ± 0.4cB | |

| SPaMe | 9.6 ± 0.4aC | 6.3 ± 0.3cB | 6.9 ± 0.2bB | 5.7 ± 0.4 dB | 6.6 ± 0.1bcB | |

The mean ± SD followed by lowercase letters in the lines do not differ by Tukey test (p < 0.05). Mean ± SD followed by upper case letters in the columns do not differ by Tukey test (p < 0.05)

nd Not detected

Higher peroxide value was initially found in soybean oil, when compared to the others. Peroxide value varies with temperature, oxygen availability, amount of oil, or surface/volume ratio [16]. With the exception of papaya and SPaMe oils, which were resistant to oxidative degradation, oils exhibited oscillations in the peroxide value during heating, probably due to decomposition of hydroperoxides, formation of hydrocarbons, short-chain fatty acids, free radicals, and volatile compounds, or reactions with natural antioxidant compounds.

Conjugated diene values indicate the content of conjugated hydroperoxides in oils and fats which has resulted from shifting of double bonds. Higher conjugated diene values represent a higher level of oxidation [17]. Melon oil showed high amount of conjugated dienoic acids. However, during the heating process, there was significant increase of conjugated dienoic acid in all oils, and soybean oil stood out in 20 h with higher amount (2.8%). It was also noted, when comparing only among the compound oils, that SMe presented the lowest formation of conjugated dienoic acids during 20 h of heating, possibly due to the synergistic effect among the compounds present in soybean and melon oils, resulting in greater protection.

The polar compounds content is a good indicator of the quality for frying oils as the polar compounds in oil contain all levels of the lipid oxidation products including primary, secondary and tertiary oxidation products [18]. It was observed that the soybean oil in the initial time presented smaller formation of total polar compounds. However, during thermoxidation, the amount of polar compounds increased in all oils, mainly in soybean oil (29%). Considering the disregard limit (24–27%) adopted by some countries such as Belgium, Chile, France, with the exception of soybean oil, all oils showed lower values at 20 h of heating, especially SPa. By relating conjugated dienoic acids with polar compounds, it is possible to infer that the soybean oil showed higher formation of primary oxidation compounds with increasing heating time.

All products from the initial oxidation can be degraded or polymerized to form secondary oxidation products. When the ρ-anisidine value, which measures the secondary products, is lower than 10, the oil is considered good [19]. Thus, it was observed that, in the initial time, all oils can be considered good, especially melon oil (0.9) and SPaMe (0.7). However, with heating, all oils reached values higher than 10, with the exception of papaya oil (7.3) in 15 h.

Totox is a measurement of overall oxidation level of oil samples, which can give a better estimation of the progressive oxidative deterioration of oil samples [5]. Also, in order to be considered well preserved, the oil must have low totox value (< 10). As shown in Table 1, at first, the oils presented good preservation conditions, except for soybean oil (10.2). However, during heating, the oils showed increase and variations in totox value. Only papaya oil (7.3) remained in good condition, which indicates it is more stable oil.

The oils are very susceptible to oxidation, which limits their use in food [20]. As shown in Table 1, initial time, it was found that papaya oil was more stable (17.3 h), although, over the course of heating, it was not possible to detect the oxidative stability in this oil. Since it is a crude oil, the formation of other compounds may have occurred, which impaired the detection of the oxidative stability. During thermoxidation, although fluctuations occurred, SPa compound oil had greater stability 20 h. Soybean oil was the only one to show decrease in oxidative stability with increased heating time. This is mainly due to the fact that soybean oil is refined, and, thus, does not contain significant amounts of interfering compounds such as soaps, phospholipids, and pigments.

Eleven different types of fatty acids were found (myristic; palmitic; stearic acid; arachidic; behenic; palmitoleic; oleic acid; eicosenoic; linoleic; α-linolenic and γ-linoleic). Amongst the saturated fatty acids, palmitic acid appeared in greater quantities during the entire thermoxidation process. As to unsaturated fatty acids, linoleic acid was the one found in highest percentage, except in papaya oil, which presented high quantity of oleic acid (64.85–70.90%). The presence of essential fatty acids, such as linoleic, makes the oils more interesting from the nutritional point of view, since these fatty acids are not produced by humans and are necessary for the formation of cell membranes, vitamin D, and several hormones [21]. On the contrary, the high quantity of oleic acid and the low percentage of polyunsaturated fatty acids are related to high resistance to thermoxidative alteration [22]. Initially, it was possible to verify that papaya oil presented greater amounts of saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, while melon oil showed greater quantity of polyunsaturated fatty acids (Table 2).

Table 2.

Fatty acid composition of the oils in thermoxidation (%)

| Oils | Time (h) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 20 | ||

| ∑saturated | S | 16.48 ± 0.04cD | 17.32 ± 0.02bC | 18.97 ± 0.01aB |

| Pa | 22.39 ± 0.05cA | 25.91 ± 0.05bA | 30.97 ± 0.02aA | |

| Me | 15.93 ± 0.01cE | 16.26 ± 0.12bE | 16.44 ± 0.02aE | |

| SPa | 17.70 ± 0.03cB | 18.36 ± 0.01bB | 18.61 ± 0.01aC | |

| SMe | 16.35 ± 0.01cD | 16.61 ± 0.02bD | 16.81 ± 0.06aD | |

| SPaMe | 17.56 ± 0.02cC | 18.41 ± 0.03bB | 18.59 ± 0.04aC | |

| ∑monounsaturated | S | 23.04 ± 0.02cD | 24.10 ± 0.01bD | 24.33 ± 0.01aC |

| Pa | 71.68 ± 0.05aA | 70.33 ± 0.04bA | 65.76 ± 0.03cA | |

| Me | 21.90 ± 0.01bF | 22.50 ± 0.02aF | 22.60 ± 0.03aD | |

| SPa | 31.90 ± 0.05cC | 33.94 ± 0.00aB | 32.53 ± 0.03bB | |

| SMe | 22.47 ± 0.03bE | 23.21 ± 0.05aE | 22.64 ± 0.06bD | |

| SPaMe | 32.31 ± 0.01bB | 32.34 ± 0.06bC | 33.04 ± 0.21aB | |

| ∑polyunsaturated | S | 60.49 ± 0.02aC | 58.58 ± 0.02bC | 56.69 ± 0.02cC |

| Pa | 5,92 ± 0.02aF | 3.75 ± 0.01bF | 3,27 ± 0.02cF | |

| Me | 62.17 ± 0.02aA | 61.39 ± 0.02bA | 60.95 ± 0.01cA | |

| SPa | 50.41 ± 0.03aD | 47.70 ± 0.02cE | 48.87 ± 0.02bD | |

| SMe | 61.18 ± 0.02aB | 60.18 ± 0.03cB | 60.43 ± 0.09bB | |

| SPaMe | 50.14 ± 0.02aE | 49.25 ± 0.05bD | 48.56 ± 0.01cE | |

The mean ± SD followed by lowercase letters in the lines do not differ by Tukey test (p < 0.05). Mean ± SD followed by upper case letters in the columns do not differ by Tukey test (p < 0.05)

The amount of saturated fatty acids increased significantly in all oils during thermoxidation, especially in papaya oil, which formed 38.32% of saturated fatty acids in 20 h of thermoxidation. As to monounsaturated fatty acids, papaya oil presented decrease in quantity (8.26%) in 20 h of heating. Furthermore, papaya oil also presented greater reduction of polyunsaturated fatty acids (44.76%) in 20 h of heating. Therefore, it is possible to infer that the increase in temperature results in the breaking of double bonds present in unsaturated fatty acids, transforming them into saturated.

Regarding the compound oils, SMe stood out, showing lower formation of saturated fatty acids (2.81%) and, consequently, lower reduction of monounsaturated (0.76%) and polyunsaturated (1.23%) fatty acids. However, it is important to emphasize that the SPaMe and SPa compound oils presented increase in the quantity of monounsaturated fatty acids, 2.26 and 1.98%, respectively, in 20 h of heating.

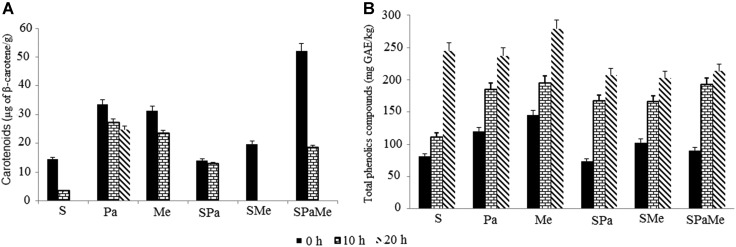

Carotenoids are antioxidants that act as electron acceptors, quenching singlet oxygen. As seen in Fig. 1, initially, the SPaMe presented higher amounts of carotenoids (52.1 μg of β-carotene/g), which showed that the papaya and melon oils contributed to increase by 3.6 times initial amount of carotenoids from soybean oil (14.4 μg of β-carotene/g).

Fig. 1.

Carotenoids (A) and total phenolic compounds (B)

During thermoxidation, there was a significant decrease in total carotenoids concentration. With 10 h of thermoxidation, the SMe no longer had carotenoids. In other oils, carotenoids were totally lost with 20 h of heating, except papaya oil that still had 24.6 μg of β-carotene/g. This greater retention of carotenoids may be attributed to the high content of monounsaturated fatty acids. Studies have shown that temperatures above 40 °C contribute to the degradation of pigments. The oxidation of carotenoids molecules results are the discoloration of pigments, the loss of biological activity and formation of degradation products such as apocarotenoides (β-apo-12-carotenal, β-apo-carotenal and β 10-apo-8-carotenal), and volatiles epoxicarotenoides [23].

Phenolic compounds are substances that act by donating electrons in order to stop the action of free radicals. As it is observed in Fig. 1 the melon oil had higher amounts of phenolic compounds, 145.3 mg GAE/kg, at the initial time. Over the thermoxidation process there was an increase in the total phenolic compounds, highlighting the soybean, SPa and SPaMe oils. This increase may be due to the reaction of the reagent Folin–Ciocalteu with phenol groups from degradation of tocopherols, since these compounds are readily oxidizable, resulting in the formation of the blue complexes, which, consequently, culminates in an overestimation of the phenolic compounds [24].

In Table 3, it is possible to see that the α-, γ- and δ-tocopherol isomer were detected in oils. Regarding isomers, all oils presented higher amounts of γ-tocopherol, except papaya oil. The papaya oil was highlighted with high amount of α-tocopherol and low level of γ-tocopherol, possibly due to a greater presence of other antioxidants such as carotenoids, and/or monounsaturated fatty acids that are able to promote the oxidative protection of the oil. The δ-tocopherol isomer was not detected in melon oil, besides being completely degraded in papaya oil after a 10 h thermoxidation.

Table 3.

Levels of the tocopherols isomers (mg/kg)

| Oils | Time (h) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 20 | ||

| α-tocopherol | S | 57.6 ± 0.1aA | 33.0 ± 0.5bD | 11.9 ± 0.5cF |

| Pa | 52.1 ± 0.7aC | 27.7 ± 0.3bE | 26.4 ± 0.5cE | |

| Me | 39.8 ± 0.2aE | 34.9 ± 0.6bC | 29.4 ± 0.3cD | |

| SPa | 53.6 ± 0.6aB | 43.5 ± 0.4cB | 45.6 ± 0.5bC | |

| SMe | 51.1 ± 0.5cC | 55.0 ± 0.2bA | 58.3 ± 0.1aB | |

| SPaMe | 43.3 ± 0.3bD | 43.6 ± 0.3bB | 60.1 ± 0.8aA | |

| γ-tocopherol | S | 383.5 ± 0.4aB | 202.7 ± 0.9bE | 66.3 ± 0.2cE |

| Pa | 29.8 ± 0.4aF | ndbF | ndbF | |

| Me | 467.7 ± 0.4aA | 295.7 ± 0.3bB | 173.4 ± 0.6cD | |

| SPa | 304.7 ± 0.4aD | 218.7 ± 0.2cD | 227.4 ± 0.4bC | |

| SMe | 363.1 ± 0.8aC | 345.3 ± 0.3bA | 289.6 ± 0.1cA | |

| SPaMe | 278.7 ± 0.3aE | 250.8 ± 0.9bC | 278.4 ± 0.5aB | |

| δ-tocopherol | S | 109.9 ± 0.3aA | 89,8 ± 0,5bA | 61.3 ± 0.5cC |

| Pa | 10.6 ± 0.6aE | ndbE | ndbD | |

| Me | ndaF | ndaE | ndaD | |

| SPa | 90.9 ± 0.3aB | 71.3 ± 0.3bC | 68.8 ± 0.3cB | |

| SMe | 83.7 ± 0.2aC | 84.2 ± 0.2aB | 74.9 ± 0.6bA | |

| SPaMe | 61.3 ± 0.6aD | 59.6 ± 0.4bD | 61.9 ± 0.6aC | |

| Total | S | 550.9 ± 0.5aA | 325.6 ± 1.8bD | 139.6 ± 0.2cE |

| Pa | 92.6 ± 1.7aF | 27.7 ± 0.3bE | 26.4 ± 0.5bF | |

| Me | 507.5 ± 0.5aB | 330.6 ± 0.6bD | 202.8 ± 0.9cD | |

| SPa | 449.2 ± 0.7aD | 333.4 ± 0.8cC | 341.8 ± 0.4bC | |

| SMe | 497.9 ± 0.8aC | 484.5 ± 0.1bA | 422.9 ± 0.5cA | |

| SPaMe | 383.3 ± 1.3bE | 353.9 ± 1.2cB | 400.4 ± 1.3aB | |

The mean ± SD followed by lowercase letters in the lines do not differ by Tukey test (p < 0.05). Mean ± SD followed by upper case letters in the columns do not differ by Tukey test (p < 0.05)

nd Not detected (δ-tocopherol ≤ 2.30 mg/kg)

In the compounds oils, mainly in SPaMe, have fluctuations in the tocopherol levels along the thermoxidation, probably because of some substances regenerative. The ascorbate, uric acid and/or reduced glutathione are substances capable of regenerating tocopherols [25].

At the end of the thermoxidation process, there were a higher retention of total tocopherols in oils SPa compounds (76.1%) and SMe (84.9%), possibly due to the synergistic effect with carotenoids and phenolic compounds.

In Table 4 it was found four different phytosterols: campesterol, stigmasterol, β-sitosterol and stigmastanol. Among the oils initially analyzed, the soybean oil showed higher amounts of campesterol (16.7 mg/100 g) and stigmasterol (22.8 mg/100 g), while the melon oil presented higher amounts of β-sitosterol (797.1 mg/100 g) and stigmastanol (60.4 mg/100 g). It is possible to verify that, in the melon oil, SMe and SPaMe were the only ones to submit stigmastanol. Although this phytosterol is saturated and less susceptible to oxidative degradation; it has a tertiary carbon, the which makes it prone to degradation and the formation of a variety of oxidized derivatives with a potential harmful effect to health [26].

Table 4.

Phytosterol composition (mg/100 g)

| Oils | Time (h) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 20 | ||

| Campesterol | S | 16.7 ± 0.1aA | 16.2 ± 0.1bA | 15.9 ± 0.1cA |

| Pa | 15.3 ± 0.1aB | 9.3 ± 0.1bD | 8.2 ± 0.1cE | |

| Me | ndaE | ndaE | ndaF | |

| SPa | 13.7 ± 0.1aC | 11.7 ± 0.1bB | 11.1 ± 0.1cB | |

| SMe | 13.3 ± 0.2aD | 10.7 ± 0.1bC | 10.1 ± 0.1cC | |

| SPaMe | 13.6 ± 0.1aCD | 9.6 ± 0.2bD | 8.8 ± 0.2cD | |

| Stigmasterol | S | 22.8 ± 0.,1aA | 22.5 ± 0.2bA | 16.8 ± 0.2cA |

| Pa | 9.4 ± 0.1aD | 8.8 ± 0.0bE | 7.5 ± 0.0cE | |

| Me | ndaE | ndaF | ndaF | |

| SPa | 15.2 ± 0.1aB | 12.2 ± 0.1bB | 11.7 ± 0.2cB | |

| SMe | 12.9 ± 0.2aC | 11.4 ± 0.1bC | 10.3 ± 0.1cC | |

| SPaMe | 13.0 ± 0.0aC | 10.4 ± 0.2bD | 8.3 ± 0.1cD | |

| β-sitosterol | S | 334.7 ± 0.1aE | 325.1 ± 0.1bD | 285.5 ± 0.2cD |

| Pa | 634.4 ± 0.1aB | 574.8 ± 0.1bB | 552.6 ± 0.1cB | |

| Me | 797.1 ± 0.1aA | 735.6 ± 0.1bA | 715.3 ± 0.1cA | |

| SPa | 310.5 ± 0.1aF | 271.8 ± 0.2bF | 267.3 ± 0.2cE | |

| SMe | 350.7 ± 0.0aD | 296.1 ± 0.0bE | 285.6 ± 0.2cD | |

| SPaMe | 423.8 ± 0.1aC | 350.5 ± 0.0bC | 346.1 ± 0.1cC | |

| Stigmastanol | S | ndaD | ndaD | ndaC |

| Pa | ndaD | ndaD | ndaC | |

| Me | 60.4 ± 0.1aA | 58.6 ± 0.1bA | 57.5 ± 0.2cA | |

| SPa | ndaD | ndaD | ndaC | |

| SMe | 14.4 0.1aC | 12.7 ± 0.4bC | 11.8 ± 0.3cB | |

| SPaMe | 15.8 ± 0.1aB | 14.1 ± 0.0bB | 11.4 ± 0.2cB | |

| Total | S | 374.3 ± 0.1aE | 363.7 ± 0.1bD | 318.1 ± 0.5cD |

| Pa | 659.0 ± 0.1aB | 592.9 ± 0.1bB | 568.3 ± 0.1cB | |

| Me | 857.5 ± 0.1aA | 794.3 ± 0.1bA | 772.8 ± 0.1cA | |

| SPa | 339.4 ± 0.1aF | 295.6 ± 0.2bF | 290.1 ± 0.4cE | |

| SMe | 391.4 ± 0.1aD | 330.9 ± 0.4bE | 317.8 ± 0.5cD | |

| SPaMe | 466.2 ± 0.3aC | 384.6 ± 0.3bC | 374.7 ± 0.4cC | |

The mean ± SD followed by lowercase letters in the lines do not differ by Tukey test (p < 0.05). Mean ± SD followed by upper case letters in the columns do not differ by Tukey test (p < 0.05)

nd not detected (stigmastanol and stigmasterol < 4.25 mg/100 g; campesterol < 5.60 mg/100 g)

There was a reduction of total phytosterols from 10 to 20% over the thermoxidation process, especially soybean and melon oils, due to the retention of campesterol and stigmastanol isomers, respectively. However, at the end of this process, it was observed that melon oil excelled with 772.8 mg/100 g of total phytosterols, corresponding to 90% retention. In the compound oils it was verified that papaya and melon oil contributed to the retention amount of phytosterols, since the oil SPaMe showed more than 17% total phytosterols when compared to soybean oil, at the end of the process. In addition, this oil showed higher retention of the β-sitosterol isomer (81.7%).

According to Ferrari et al. [27], the susceptibility of phytosterols to oxidation by reactive oxygen species, light, metal ions and high temperatures depends on their unsaturation level, thus, the isomer that presented the lowest retention in 20 h was campesterol of papaya oil (53.6%).

Antioxidant capacity

Antioxidants may exhibit synergistic effect or not, and may act via hydrogen atom transfer, and/or an electron. Thus, there are several different methods for the evaluation of the antioxidant capacity [28].

The DPPH˙ (radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) method is based on the ability of DPPH˙ to react with hydrogen donors. Among the oils initially analyzed (Table 5), the soybean oil showed higher antioxidant capacity, followed by the SMe compound (85.5%). In the thermoxidation course, only the soybean oil, had a decrease in its antioxidant activity, reaching the lowest value at 20 h. Fluctuations were also detected in other oils, which was possibly caused by the presence of interfering compounds that overestimate the value of the DPPH˙ percentage of removal, they present themselves with maximum absorbance in the same spectral region of the other compounds [29]. It can also because of DPPH˙ stoichiometry reaction which differs with the type of antioxidant, or may be 2:1 or 3:1 (radical/antioxidant), depending on the number of hydroxyl groups [30] or due to possible synergistic effect of the molecules antioxidants during heat application.

Table 5.

Antioxidant activity

| Oils | Time (h) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 20 | ||

| DPPH˙ (%) | S | 94.6 ± 1.2aA | 82.9 ± 1.2bC | 62.2 ± 0.2cF |

| Pa | 67.3 ± 0.4bD | 71.8 ± 0.2aD | 68.5 ± 0.7bE | |

| Me | 61.3 ± 0.2cE | 81.0 ± 2.1aC | 74.9 ± 0.6bD | |

| SPa | 79.0 ± 0.6cC | 86.3 ± 0.1bB | 91.6 ± 0.1aA | |

| SMe | 85.5 ± 0.4cB | 92.1 ± 0.5aA | 89.1 ± 0.2bB | |

| SPaMe | 79.2 ± 0.4bC | 85.6 ± 1.1aB | 86.3 ± 0.2aC | |

| ABTS˙+ (µM trolox/100 g) | S | 13.2 ± 0.3aD | 5.0 ± 0.5bE | 5.5 ± 0.3bD |

| Pa | 31.3 ± 0.5aA | 7.1 ± 0.9cD | 10.0 ± 0.8bC | |

| Me | 8.4 ± 0.5cE | 11.2 ± 1.0bBC | 17.5 ± 0.7aB | |

| SPa | 9.9 ± 0.6cE | 11.5 ± 0.7bB | 43.9 ± 0.8aA | |

| SMe | 28.5 ± 1.3aB | 20.5 ± 0.7bA | 4.5 ± 0.3cD | |

| SPaMe | 19.6 ± 1.7aC | 9.4 ± 1.2bC | 4.5 ± 0.0cD | |

| FRAP (µM trolox/100 g) | S | 76.1 ± 3.5cE | 125.9 ± 3.3aA | 114.5 ± 4.9bB |

| Pa | 118.2 ± 3.9aD | 116.2 ± 2.5aB | 103.2 ± 4.8bC | |

| Me | 185.9 ± 4.9aA | 126.6 ± 0.8bA | 106.9 ± 3.3cBC | |

| SPa | 110.1 ± 0.3aD | 73.5 ± 5.5bD | 80.4 ± 5.9bD | |

| SMe | 137.2 ± 3.3aC | 119.5 ± 6.5bBA | 110.9 ± 3.1cBC | |

| SPaMe | 148.8 ± 1.6aB | 96.1 ± 1.7bC | 143.4 ± 4.1aA | |

| β-carotene/linoleic acid (%) | S | 70.5 ± 1.0aA | 29.8 ± 1.7bD | 73.5 ± 0.2aA |

| Pa | 41.8 ± 0.2aC | 11.2 ± 0.9cE | 22.9 ± 1.4bE | |

| Me | 61.5 ± 0.9aB | 34.9 ± 3.8cD | 51.1 ± 0.7bC | |

| SPa | 43.6 ± 1.4bC | 70.9 ± 4.2aB | 11.8 ± 0.0cF | |

| SMe | 46.7 ± 4.1bC | 61.0 ± 0.6aC | 37.9 ± 0.6cD | |

| SPaMe | 46.3 ± 3.4cC | 82.5 ± 2.1aA | 56.5 ± 2.2bB | |

The mean ± SD followed by lowercase letters in the lines do not differ by Tukey test (p < 0.05). Mean ± SD followed by upper case letters in the columns do not differ by Tukey test (p < 0.05)

In the antioxidant ABTS˙+ method, papaya oil showed 31.3 µM trolox/100 g at the beginning of thermoxidation process. At the end of the process, there was a decrease in the antioxidant activity of SMe and SPaMe oils, reaching 4.5 µM trolox/100 g, whose reductions were 16 and 23%, respectively. Other oils showed fluctuations and/or increased during thermoxidation, in addition to this, it is possible to say that this oscillation happens because of the ABTS˙+ radical reactions with phenolic compounds, which it is conclude in two steps. In the first step, a radical molecule abstracts an electron, or even a hydrogen atom from a phenolic compound, in order to form a semiquinone radical. In the second part of the process, the semiquinone radical reacts with another radical molecule of ABTS˙+, forming an unstable product easily degraded into other compounds. Thus, it is possible to prove the cause of the concentration’s changes in ABTS˙+ radical and its disappearance in the measurement system, due to the reduction and degradation processes [31].

During the FRAP process, melon oil initially obtained the higher value, 185.9 µM trolox/100 g, in contrast, the papaya and SPa oils demonstrated greater stability along the thermoxidation, since no significant differences (p < 0.05) were found. This may be due to the papaya oil is high amount of antioxidants. Only soybean, SPa and SPaMe oils showed thermoxidative oscillations during the process, which was possibly caused by the high concentrations of pro-oxidant compounds, such as carotenoids and tocopherols, especially when the oxygen concentration is high, as result of the light energy absorbed by these pigments, pigments that by its turn, can be transferred to the triplet oxygen, becoming what it is called singlet, a more reactive kind of oxidizing agent [32]. In addition, may also have occurred antagonistic effect between the action of β-carotene and tocopherol, as the oil protected worse in the presence of carotenoid than without it [33].

In β-carotene/linoleic acid analysis, soybean oil had a higher antioxidant activity early in the process. In the course of thermoxidation, all oils showed fluctuations in antioxidant activity, probably in view of the presence of metals (copper, iron and zinc) and of the β-carotene ratio, linoleic acid and water in the preparation of the emulsion, which influence on the concentration of β-carotene that may remain [34]. Furthermore, this assay measures lipophilic antioxidants [35] and carotenoids may have acted as pro-oxidants initially thermoxidation since after the concentration has decreased.

Thus, it is concluded that papaya and melon oils used together with the soybean oil have good physico-chemical quality. By means of thermoxidation, observed that papaya and melon oils increase the nutritional value and stability of the soybean oil, with retention of carotenoids, phytosterols, and tocopherols. Furthermore, the use of papaya and melon seeds for the oil extraction minimizes the environmental impact of the agro-industrial residues.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - CAPES, for sponsoring the research; The National Council of Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq, for sponsoring the productivity; Foundation for the Development of UNESP - FUNDUNESP, for financial support and companys Triângulo Alimentos® and Demarchi, for the donation of soybean oil and papaya seeds, respectively.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Silva AC, Jorge N. Bioactive compounds of the lipid fractions of agro-industrial waste. Food Res. Int. 2014;66:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.10.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porte A, Silva EF, Almeida VDS, Silva TX, Porte LHM. Propriedades funcionais tecnológicas das farinhas de sementes de mamão (Carica papaya) e de abóboras (Cucurbita sp) Rev. Bras. Prod. Agro. 2011;13:91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steenson DF, Min DB. Effects of β-carotene and lycopene thermal degradation products on the oxidative stability of soybean oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2000;77:1153–1160. doi: 10.1007/s11746-000-0181-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karpinska M, Borowski J, Danowska-Oziewicz M. The use of natural antioxidants in ready-to-serve-food. Food Chem. 2001;72:5–9. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00171-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Brien RD. Fats and oils: formulating and processing for applications. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brasil. Resolução RDC n. 270, de 22 de setembro de 2005. Aprova o regulamento técnico para óleos vegetais, gorduras vegetais e creme vegetal. Diário Oficial [da] República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, Distrito Federal (2005)

- 7.AOCS. Official methods and recommended practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society. 6th ed. American Oil Chemits’ Society, Champaing, IL, USA (2009)

- 8.Hartman L, Lago RCA. Rapid preparation of fatty acid methyl esters from lipids. Lab. Pract. 1973;22:475–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez-Amaya DB. A guide to carotenoids analysis in food. Washington: ILSI Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic and phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965;16:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duchateau GSMJE, Bauer-Plank CG, Louter AJH, Van der Ham M, Boerma JA, Van Rooijen JJM, Zandbelt PA. Fast and accurate method for total 4-desmethy sterol(s) content in spreads, fat-blends a raw material. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 79:273–278 (2002)

- 12.Kalantzakis G, Blekas G, Pegklidou K, Boskou D. Stability and radical-scavenging activity of heated olive oil and other vegetable oils. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Tech. 2006;108:329–335. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200500314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 1999;26:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szydlowska-Czerniak A, Karlovits G, Dianoczki C, Recseg K, Szłyk E. Comparison of two analytical methods for assessing antioxidant capacity of rapessed and olive oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2008;85:141–149. doi: 10.1007/s11746-007-1178-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller HE. A simplified method for the evaluation of antioxidants. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1971;48:91. doi: 10.1007/BF02635693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nawar WW. In Fennema OR (ed) Lipids in Food Chemistry. New York, USA: Marcel Decker Inc (1996)

- 17.Lukesová D, Dostálová J, Mahmoud EEM, Svárovská M. Oxidation changes of vegetable oils during microwave heating. Czech J. Food Sci. 2009;23:230–239. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen WA, Chiu C, Cheng WC, Hsu CK, Kuo MJ. Total polar compounds and acid values of repeatedly used frying oils measured by standard and rapid methods. J. Food Drug Anal. 2013;21:58–65. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillén MD, Cabo N. Fourier transform infrared spectra data versus peroxide and anisidine values to determine oxidative stability of edible oils. Food Chem. 2002;77:503–510. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(01)00371-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunstone FD. Vegetable oils in food technology: composition, properties and use. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fruhwirth GO, Hermetter A. Seeds and oil of the Styrian oil pumpkin: components and biological activities. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Tech. 2007;109:1128–1140. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200700105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jorge N, Gonçalves LAG. Comportamento do óleo de girassol com alto teor de ácido oleico em termoxidação e fritura. Food Sci. Tech. 1998;18:1–15. doi: 10.1590/S0101-20611998000300015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azevedo-Meleiro CH, Rodriguez-Amaya DB. Carotenoid composition of kale as influenced by maturity, season and minimal processing. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005;85:591–597. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prior RL, Wu X, Schaich K. Standardized methods for de determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:4290–4302. doi: 10.1021/jf0502698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolf K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz S. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. Boston: MacGrow Hill; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudzinska M, Przybylski R, Wasowicz E. Degradation of phytosterols during storage of enriched margarines. Food Chem. 2014;142:294–298. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrari RA, Schulte E, Esteves W, Brühl L, Mukherjee KD. Minor constituents of vegetable oils during industrial processing. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1996;73:587–592. doi: 10.1007/BF02518112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsao R, Deng Z. Separation procedures for naturally occurring antioxidant phytochemicals. J. Chromat. 2004;812:85–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang D, Ou B, Prior RL. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:1841–1856. doi: 10.1021/jf030723c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnao MB. Some methodological problems in the determination of antioxidant activity uusing chromogen radicals: a practical case. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2000;11:419–421. doi: 10.1016/S0924-2244(01)00027-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osman AM, Wong KKY, Fernyhough A. ABTS radical driven oxidation of polyphenols: isolation and structural elucidation of covalent adducts. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Comm. 2006;346:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castelo-Branco VN, Torres AG. Capacidade antioxidante total de óleos vegetais comestíveis: determinantes químicos e sua relação com a qualidade dos óleos. Rev. Nut. 24:173–187, 2011 (2011)

- 33.Smyk B. Singlet oxygen autosidation of vegetable oils: Evidence for lack of synergy between β-carotene and tocopherols. Food Chem. 2015;182:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dawidowicz AL, Olszowy M. Influence of some experimental variables and matrix components in the determination of antioxidant properties by β-carotene bleaching assay: experiments with BHT used as standard antioxidant. Eur. Food Res. Tech. 2010;231:835–840. doi: 10.1007/s00217-010-1333-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiokias S, Varzakas T, Oreopoulou V. In vitro activity of vitamins, flavonoids and natural phenolic antioxidants against the oxidative deterioration of oil-based systems. Critical Rev. Food Sci. Nut. 2008;48:78–93. doi: 10.1080/10408390601079975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]