Abstract.

Lymphatic filariasis is a mosquito-borne parasitic infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia spp. Commonly seen in tropical developing countries, lymphatic filariasis occurs when adult worms deposit in and obstruct lymphatics. Although not endemic to the United States, a few cases of lymphatic filariasis caused by zoonotic Brugia spp. have been reported. Here we present a case of an 11-year-old female with no travel history who was seen in our clinic for a 1-year history of painless left cervical lymphadenopathy secondary to lymphatic filariasis. We review the literature of this infection and discuss the management of our patient. Using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient care database in the United States, we also examine the demographics of this infection. Our results show that chronic lymphadenopathy in the head and neck is the most common presenting symptoms of domestic lymphatic filariasis. Diagnosis is often made after surgical lymph node excision. Examination of the NIS from 2000 to 2014 revealed 865 patients admitted with a diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis. Most patients are in the mid to late sixties and are located on the eastern seaboard. Eight hundred and twenty six cases (95.5%) were likely due to zoonotic Brugia spp. and 39 (4.5%) due to W. bancrofti. Despite being rare, these data highlight the need to consider filariasis in patients presenting with chronic lymphadenopathy in the United States.

INTRODUCTION

Filariasis is a parasitic disease caused by an infection of filarial (from the Latin filum “thread”) nematodes, a genus of helminths that are transmitted by blood-sucking vectors and reside in specific locations within their hosts.1 There are a number of notable species within this category. Dirofilaria is the organism that causes heartworm in canines. Loa loa, also known as African eye worm, is commonly found in the conjunctiva. Onchocerca volvulus, the causative agent of river blindness, is typically found in subcutaneous nodules or the small vessels perforating the ciliary body in the eye.1

Lymphatic filariasis is typically caused by three species that preferentially reside in the host lymphatics and include Wuchereria bancrofti (Bancroftian filariasis), which accounts for 90% of all cases, Brugia malayi (malayan filariasis), and Brugia timori.2,3 Lymphatic filariasis currently affects an estimated 67.88 million people worldwide.4 The condition is endemic to the tropical regions of South America, Oceania, Africa, and Asia but rarely found in the United States.5 The few cases that have been reported in North America were found in patients who did not travel to endemic areas and were caused by zoonotic forms of the disease.6,7

Despite an abundance of literature on the burden of lymphatic filariasis in endemic regions, a paucity of data exists on the occurrence of this disease in the United States. Twenty-eight cases have been published in the United States, most commonly by Brugia beaveri, which has been isolated in bobcats in Florida and Brugia lepori, which infected 60% of wild rabbits mainly in Nantucket, MA.6–14 Although these case reports have provided us with a substantial amount of information regarding zoonotic infections, they only reflect a small portion of cases. The true burden of zoonotic and endemic forms of lymphatic filariasis in the United States remains unknown.

Here we discuss a case of an 11-year-old female from Massachusetts with no travel history presenting with an enlarged cervical lymph node caused by lymphatic filariasis. We perform a literature review of lymphatic filariasis in the United States. In addition, we evaluated all lymphatic filariasis–related hospitalizations between 2000 and 2014 using the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) to quantify the burden in the United States.

METHODS

Case report and literature review.

A retrospective chart review of a single case at an urban medical center was performed. Clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic data were collected and reviewed. Hematoxylin and eosin stains of the specimen were sent to a regional academic medical center for diagnosis. The diagnosis was confirmed by the Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria (DPDx) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Atlanta, GA). A systematic search in Ovid MEDLINE and Google Scholar were conducted. Relevant synonyms for the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms “lymphatic filariasis” were used to compile an initial list of articles. Relevant articles were isolated after reviewing abstracts. Articles not written in English were excluded. Selected articles were manually reviewed for relevant cross-references.

Database analysis.

Demographic information was obtained from 115,740,165 discharges from the NIS between 2000 and 2014 providing us with a weighed sample size of an estimated 567,707,847 (±10,456) patients. The NIS is a nationwide all-payer inpatient database released by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Each yearly release contains the patient demographics, ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes, charges, and discharge information of ∼8 million inpatients, which corresponds to ∼20% of all hospitalizations in the United States.15

Patients discharged with a diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis due to either W. bancrofti (ICD-9-CM codes 125.0) or Brugia spp. (ICD-9-CM code 125.1) were used to create the cohort of patients with lymphatic filariasis. The ICD-9-CM code 125.5 (filariasis not Elsewhere Classified) was also analyzed for patients who had any sequela of lymphatic involvement (Table 1) and added to this cohort. The hospitals in the NIS are stratified into nine regional divisions used by the U.S. Census Bureau: New England, Mid Atlantic, East North Central, West North Central, South Atlantic, East South Central, West South Central, and Mountain. The total number of patients with lymphatic filariasis was determined for each geographic region. To evaluate whether incidence of admission is affected by age, a subcohort of patients divided by age was created. Demographic information between different agents of lymphatic filariasis was compared. The mean and median length of stay was determined. The cost of admission was calculated by adjusting the total charges of an admission using the cost-to-charge ratios provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Table 1.

To include patients with zoonotic forms of lymphatic filariasis, patients with “Filariasis NEC” (ICD-9-CM 125.1) were examined for any diagnoses codes that suggested a sequela of lymphatic disease

| Associated diagnoses | ICD-9-CM |

|---|---|

| Cellulitis of leg | 682.6 |

| Other lymphedema | 457.1 |

| Noninfected lymph disease NEC | 457.8 |

| Cellulitis of foot | 682.7 |

| Joint contracture of the leg | 718.46 |

| Lymphomas NEC/lymph nodes of multiple sites | 202.88 |

| Ulcer other part low limb | 707.19 |

| Ulcer other part of foot | 707.15 |

| Venous insufficiency NOS | 459.81 |

NEC = not elsewhere classifiable; NOS = not elsewhere specified.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Per the privacy agreement with HCUP, the exact sample size of any cohort of patients with N < 11 was omitted to protect confidentiality. The data were weighed to give an accurate estimate of the number of patients admitted to hospitals in the United States. All estimates, calculated means and medians are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The trend in the number of admissions was evaluated by looking at the yearly incidence of admission and performing a regression analysis. The analysis of variance and F Value was determined to assess the significance of our regression model. Z-tests were performed to make pairwise comparisons.

RESULTS

Case report.

An 11-year-old female was seen at our otolaryngology outpatient clinic with a 1-year history of enlarged painless left cervical lymphadenopathy. The mass had never been erythematous, and she had never displayed any signs of a systemic infection, including fevers or chills. She had never traveled outside the United States and denied any exposures to animals. On examination, a single 4 × 3 cm, mobile, nontender left level II neck mass with a rubbery consistency was palpated (Figure 1). The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. computed tomography (CT) revealed a nonspecific enlarged left level II and bilateral level V adenopathy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a macrolobulated T2 hyperintense lymph node measuring 2.0 × 4.6 × 1.9 cm in the left side of the neck along the anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The lesion demonstrates mild diffuse enhancement and demonstrates intermediate signal intensity on T1 (Figure 2). She underwent an excisional biopsy of the left neck mass, which she tolerated without any complications. The fascia of the lymph nodes was not violated during surgery. Histopathologic examination revealed filarial worm fragments in the perinodal lymphatic space that, in the absence of a travel history, likely represented North American Brugia spp. (Figure 3). No serologic or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was performed however the histopathological diagnosis was confirmed by the CDC DPDx program. Despite the insistence of both the surgical team and the patient’s primary care physician, the family never followed up with an infectious disease specialist and, to the authors’ knowledge, has not been treated with any antihelmintics to date.

Figure 1.

The presenting mass was a single 4 × 3 cm, mobile, nontender left level II lymph node with a rubbery consistency in an 11-year-old female. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Figure 2.

(Left) MRI T2 coronal with fat suppression. Here the lesion appears hyperintense. (Right) MRI T1 postcontrast. The lesion shows mild diffuse enhancement.

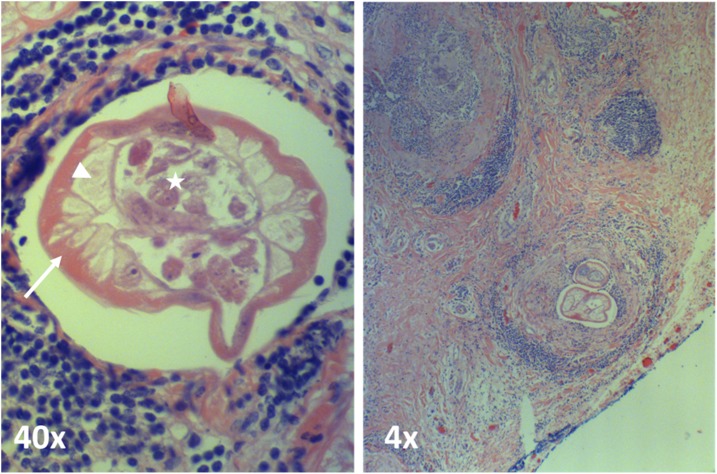

Figure 3.

H&E stain of North American Brugia spp. in a lymph node excised from the left neck. Filarial worm fragments in perinodal lymphatic space can be seen. Typical Brugia features are highlighted: thin cuticle (arrow), typical muscles (arrowhead), and the paired uteri filling pseudocoele pathognomonic of a female worm (star). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Database analysis.

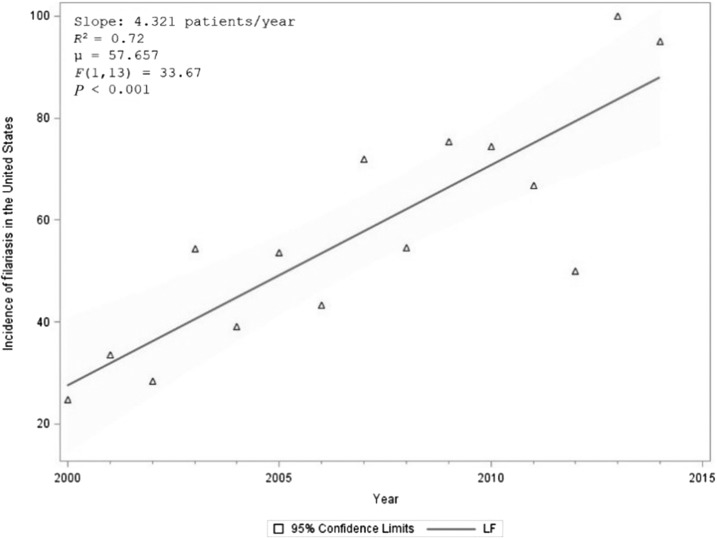

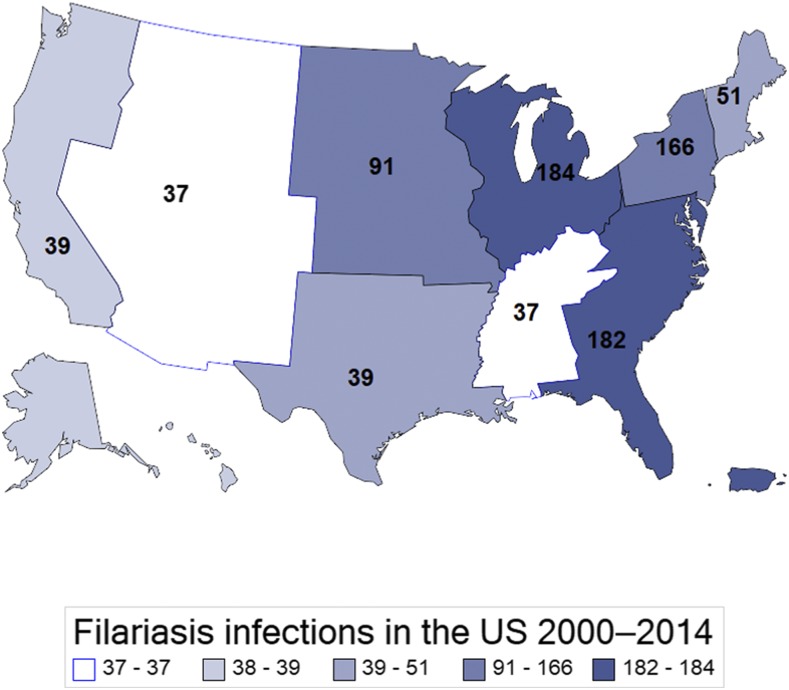

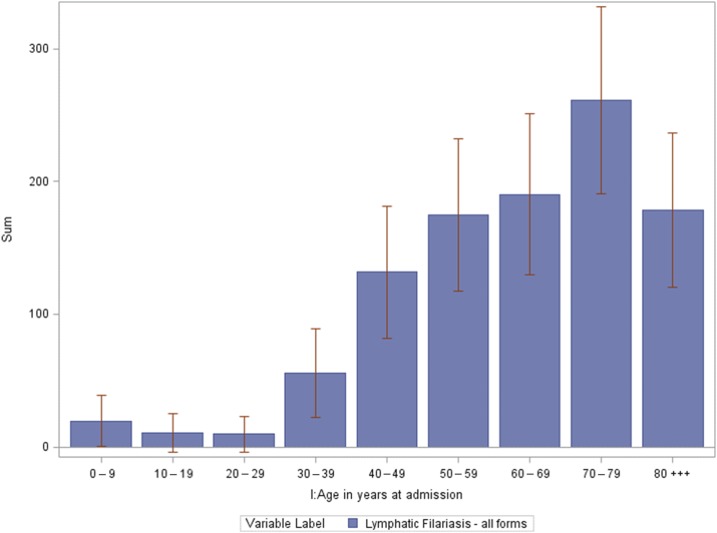

Between 2000 and 2014, an estimated 865 (95% CI: 736–994) patients with lymphatic filariasis were admitted to hospitals in the United States–approximately 58 admissions every year. The number of patients with lymphatic filariasis has increased over time (R2 = 0.72, F (1, 13) = 33.67, P < 0.001) (Figure 4). Of those admissions, 39 (95% CI: 33–44) were coded as Wuchereria spp. and 751 (95% CI: 740–761) were coded as Brugia spp. and 75 (95% CI: 37–113) were due to nonclassifiable forms of lymphatic filariasis. Demographic information on each form of lymphatic filariasis is presented in Table 2. Overall, 59.2% (N = 512) of patients with lymphatic filariasis in the United States were white, 16.0% (N = 138) were black and 5.9% (N = 51) were Hispanic. 49.9% (N = 432) were male and 50.1% (N = 433) were female. When comparing the demographics of all admitted patients in the United States with our cohort, patients admitted with lymphatic filariasis were more likely to be male (P < 0.001) and white (P = 0.013) (Table 3). Most patients were admitted in the East North Central (21.33%), South Atlantic (21.01%) and Mid Atlantic (19.18%) states (Figure 5). A higher number of patients were seen in the East North Central (WI, MI, IL, IN, OH) than expected (P = 0.032). Patients with lymphatic filariasis were more likely to be admitted to urban teaching hospitals (P < 0.001) and be discharged to an intermediate care facility or with a home health-care plan (P < 0.001) (Table 3). The mean and median age of those admitted was 64.5 years old (95% CI: 62.2–67.1) and 67.5 (95% CI: 63.2–71.8), respectively (Figure 6). Length of stay and the cost associated with admissions are presented in Table 4.

Figure 4.

Graph showing the number of lymphatic filariasis–related admissions per year from 2000 to 2014 along with a linear regression and ANOVA test results to assess significance. The reported prevalence is increasing over time. Data obtained from the National Inpatient Sample.

Table 2.

Demographics of patients in the National Inpatient Sample with lymphatic filariasis from endemic Wuchereria spp. and suspected zoonotic infections by Brugia spp. and nonclassifiable (NEC) forms of lymphatic filariasis from 2000 to 2014. 95% CI included

| Endemic lymphatic filariasis | Zoonotic lymphatic filariasis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wuchereria spp. | Brugia spp. | NEC filariasis | |||||||

| Sum | 95% CI | (%) | Sum | 95% CI | (%) | Sum | 95% CI | (%) | |

| Total | 39 | (33–44) | 100.0 | 751 | (741–761) | 100.0 | 75 | (37–113) | 100.0 |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 29 | (3–55) | 74.4 | 362 | (278–445) | 48.2 | 41 | (13–69) | 54.7 |

| Female | 10 | (−4 to 23) | 25.6 | 389 | (304–475) | 51.8 | 34 | (9–59) | 45.3 |

| Race | |||||||||

| White | 16 | (−2 to 35) | 41.0 | 466 | (372–560) | 62.1 | 30 | (6–54) | 40.0 |

| Black | 12 | (−5 to 30) | 30.8 | 120 | (72–169) | 16.0 | 5 | (−5 to 16) | 6.7 |

| Hispanic | * | * | * | 31 | (6–56) | 4.1 | 20 | (0–40) | 26.7 |

| Other/N.R. | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | – | |

| Location | |||||||||

| New England | 12 | (−5 to 28) | 30.8 | 40 | (12–67) | 5.3 | * | * | * |

| Mid-Atlantic | * | * | * | 136 | (84–187) | 18.1 | 26 | (3–48) | 34.7 |

| East North Central | * | * | * | 174 | (116–232) | 23.2 | * | * | * |

| West North Central | * | * | * | 86 | (45–127) | 11.5 | * | * | * |

| South Atlantic | * | * | * | 162 | (107–216) | 21.6 | * | * | * |

| East South Central | * | * | * | 32 | (8–56) | 4.3 | * | * | * |

| West South Central | * | * | * | 34 | (9–59) | 4.5 | * | * | * |

| Mountain | * | * | * | 33 | (8–57) | 4.4 | * | * | * |

| Pacific | * | * | * | 24 | (3–45) | 3.2 | 15 | (−2–31) | 20.0 |

CI = confidence intervals; NEC = not elsewhere classifiable.

N < 11 (not reportable based on data-use agreements).

Table 3.

Demographics of patients in the National Inpatient ample with lymphatic filariasis compared with all inpatients admitted from 2000 to 2014

| Lymphatic filariasis | All admitted patients | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 432 | 49.95 | 235,291,959 | 41.45 | <0.001 |

| Female | 433 | 50.05 | 331,377,715 | 58.37 | <0.001 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 512 | 59.22 | 305,005,305 | 53.73 | 0.013 |

| Black | 138 | 15.98 | 64,864,739 | 11.43 | 0.095 |

| Hispanic | 51 | 5.93 | 57,685,893 | 10.16 | 0.322 |

| Asian | * | * | 11,877,926 | 2.09 | * |

| Native American | * | * | 2,721,650 | 0.48 | * |

| Other | * | * | 15,396,445 | 2.71 | * |

| US regional division | |||||

| New England | 51 | 5.95 | 16,299,635 | 2.87 | 0.194 |

| Mid-Atlantic | 166 | 19.18 | 80,672,735 | 14.21 | 0.068 |

| East North Central | 184 | 21.33 | 88,317,689 | 15.56 | 0.032 |

| West North Central | 91 | 10.50 | 42,263,570 | 7.44 | 0.269 |

| South Atlantic | 182 | 21.01 | 126,067,819 | 22.21 | 0.697 |

| East South Central | 37 | 4.29 | 29,653,810 | 5.22 | 0.801 |

| West South Central | 39 | 4.55 | 62,483,102 | 11.01 | 0.205 |

| Mountain | 37 | 4.27 | 30,580,132 | 5.39 | 0.765 |

| Pacific | 39 | 4.49 | 79,039,827 | 13.92 | 0.097 |

| Income quartile | |||||

| < 25th | 207 | 23.93 | 137,359,883 | 24.20 | 0.928 |

| 25–50th | 244 | 28.20 | 142,691,891 | 25.13 | 0.270 |

| 51–75th | 182 | 21.02 | 134,444,979 | 23.68 | 0.400 |

| > 75th | 216 | 24.99 | 140,319,408 | 24.72 | 0.927 |

| Disposition of patient | |||||

| Routine | 446 | 51.55 | 415,268,244 | 73.15 | <0.001 |

| Short-term hospital | 24 | 2.78 | 12,494,993 | 2.20 | 0.848 |

| SNF or intermediate care center | 205 | 23.76 | 70,493,502 | 12.42 | <0.001 |

| Home health care | 159 | 18.37 | 51,912,343 | 9.14 | <0.001 |

| AMA | * | * | 5,231,554 | 0.92 | * |

| Died in hospital | 15 | 1.77 | 11,629,421 | 2.05 | 0.940 |

| Discharged alive | * | * | 212,935 | 0.04 | * |

| Hospital type | |||||

| Rural | 77 | 8.85 | 73,483,687 | 12.94 | 0.288 |

| Urban nonteaching | 274 | 31.73 | 227,998,728 | 40.16 | 0.005 |

| Urban teaching | 509 | 58.90 | 264,255,580 | 46.55 | <0.001 |

AMA = against medical advice; SNF = skilled nursing facility.

N < 11 (not reportable based on data-use agreements). P value: z-test for pairwise comparison of proportions. P values under 0.05 are in bold to indicate significance.

Figure 5.

Number of patients admitted with lymphatic filariasis to U.S. hospitals by location. Data obtained from the National Inpatient Sample between 2000 and 2014 from. The map is divided into the nine geographical divisions of the U.S. Census Bureau. Most patients were diagnosed on the eastern seaboard. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Figure 6.

The number of patients admitted with lymphatic filariasis by age in the United States of America between 2000 and 2014. 95th percentile confidence intervals (CI) are shown. The mean and median age of those admitted was 64.5 years old (95% CI: 62.2–67.1) and 67.5 (95% CI: 63.2–71.8), respectively. Data from the National Inpatient Sample. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Table 4.

The cost of care and length of admission for patients with all forms of lymphatic filariasis in the United States

| Mean | 95% CI | Median | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total costs ($) | $11,467 | ($9,399–$13,535) | $7,405 | ($5,843–$8,967) |

| Length of stay (days) | 5.9 | (4.96–6.84) | 3.2 | (2.63–3.76) |

CI = confidence intervals. Mean and median values presented with 95% CI.

DISCUSSION

All 29 reported cases of zoonotic lymphatic filariasis in the United States have presented with chronic lymphadenopathy −11 (37.9%) of which involved the head and neck.9 As patients with zoonotic lymphatic filariasis rarely display systemic signs of an infection, many of these patients are referred to a surgeon, such as an otolaryngologist, for an excision biopsy to obtain a diagnosis.7,9 Therefore, the diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis is often only made after an affected lymph node has been excised, as was the case in our patient.14 Because of the limited number of cases in which imaging has been performed, the utility of CT or MRI is not well established.16 In our patient, MRI revealed an isointense lesion on T1 and hyperintense lesion on T2 or short-TI inversion recovery sequences, which is congruent with other case reports.17 Although not applied in this case, ultrasonography may assist with diagnosis as it can demonstrate multiple linear echogenic structures that may have motion consistent with the movement of adult filarial worms.18 In the past, diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis relied on histopathological examination of biopsied tissue or the identification of microfilariae either on blood smears or fine needle aspiration of affect lymph nodes.19–21 However, newer enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and PCR diagnostics are available and useful for confirming speciation.22,23 In this case, the diagnosis of zoonotic Brugia spp. was made on histopathological examination and confirmed by the DPDx at the CDC. Unfortunately, because the patient did not present for follow-up care, no additional testing was performed.

No consensus on treatment of zoonotic lymphatic filariasis exists because of the rarity of the condition. Patients rarely have circulating microfilariae so surgical excision of the affected lymph node is often curative and withholding antihelminth treatment post excision may be reasonable if patients remain asymptomatic.7,9,12

In endemic regions, the current treatment consists of diethylcarbamazine (DEC) 6 mg/kg/day divided into three doses.24 It is typically given as a 12-day course however a single dose may be just as effective.2,24–27 Some authors advocate for the addition of 4–6 week course of doxycycline 200 mg/day, which targets Wolbachia, the intracellular bacterial symbiont of Wuchereria bancroft and Brugia spp.2,28 Ivermectin, given as a single 200- or 400-μg/kg dose has an efficacy similar to DEC and can be used as a monotherapy or in combination with DEC to augment its microfilarial activity.26,27,29,30 It is often used in lieu of DEC in areas where onchocerciasis is endemic– to avoid the severe adverse events related to killing of microfilariae.30,31 For a similar reason, albendazole is often used as a pretreatment before administration of DEC in patients with high circulating levels of L. loa microfilariae.31,32 Surgical excision is not considered part of standard treatment of lymphatic filariasis in endemic areas. Although numerous case reports have described excision biopsies of affected lymph nodes without any apparent complications, it is unknown whether intraoperative violation of the specimen would lead to an anaphylactic reaction similar to those reported in hydatid cyst excisions.21,33–36

To our knowledge, no studies exist that quantify the burden of zoonotic or endemic forms lymphatic filariasis in the United States. The literature suggests that the vast majority of zoonotic cases are found in the Northeastern and mid-Atlantic states and are either due to B. beaveri or B. lepori and to our knowledge, Bancroftian and malayan filariasis in the United States has not been reported.9 As previous studies have shown, the use of the NIS can be useful when quantifying domestic burdens of tropical parasitic diseases in a large sample size.37

Our results demonstrate 58 patients a year are admitted with a diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis in the United States and that the incidence is slowly rising (Figure 4). More cases were seen in the East North Central states than expected (P = 0.032). Although the number of males and females with lymphatic filariasis was nearly equal, females are overrepresented in the NIS therefore the incidence of infection in males was higher than expected (P < 0.001) (Table 3). These data are consistent with previous reports that have shown that men have a higher incidence of infection and lymphatic filariasis.38 Patients with lymphatic filariasis were more likely to be seen in urban nonteaching (P = 0.005) and urban teaching hospitals (P < 0.001) and less likely to be discharged home (P < 0.001) than the average inpatient (Table 3).

Most commonly, these patients are in their mid to late sixties (Figure 6). The median length of stay is 3.2 (2.63–3.76) days and median cost of care is $7,405 ($5,843–$8,967) (Table 4). Patients are typically discharged home (51.2%) however, they are more likely to use an intermediate care facility (23.8%) or require a home care plan (18.4%) compared with other admissions (Table 3).

More than 90% of lymphatic filarial infections in endemic regions are caused by W. bancrofti.3 It is also the only causative agent in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean, the closest endemic regions to the United States and therefore was expected to be the predominant source of either travel or potential mosquito-borne vectors into the United States.39,40 However, only 4.5% of patients were diagnosed with Bancroftian filariasis. Our results did show a high incidence of lymphatic filariasis in the South and mid-Atlantic states, although the highest incidence of disease was seen in the East North Central states (Figure 6).

Interestingly, the most commonly coded form of lymphatic filariasis was ICD-9 125.1 (86.8% of patients), which, depending on interpretation, can refer to lymphatic filariasis caused by B. malayi or all Brugia spp. We suspected that these cases reflected zoonotic cases of lymphatic filariasis caused by Brugia spp. rather than endemic cases of B. malayi for a number of reasons. No domestic cases of B. malayi have been documented in the literature. If these cases were travel-related cases of B. malayi, we would have expected the number of cases on the west coast to be much higher. Also, no known animal reservoir for B. malayi exists in the United States, although domestic cats have served as animal reservoirs for B. malayi in endemic areas such as Thailand and have acted as reservoirs for other Brugia spp. in California.41–44 To confirm these suspicions, our team reached out to the two laboratories that perform the most filarial serology testing in the United States: the CDC’s DPDx and the National Institutes of Health’s Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases. Both mentioned that they could not recall a case of B. malayi in the United States (private correspondence, February 7, 2018). Therefore, we suspect that this case, along with the 8.67% of patients diagnosed with nonclassifiable forms of lymphatic filariasis, likely represent the burden of zoonotic filariasis in the United States.

Our results show that of these cases, 23.2% were diagnosed in the East North Central states, 21.6% in the South Atlantic, and 18.1% in the mid-Atlantic states. This differs from the literature where 12 of the now 29 reported cases (41.4%) of zoonotic lymphatic filariasis were also found in the mid-Atlantic states.9

Inherent limitations to our study and the use of the NIS database should be noted. The data in the NIS are anonymous and readmissions are not flagged therefore the same patient may account for multiple entries. The dataset does not record travel history nor does it contain data from laboratory or pathology reports. In addition, the use of ICD-9 codes is limiting and impacts the accuracy of our data analysis. As mentioned, both zoonotic filariasis and malayan filariasis are caused by the Brugia spp., and although the evidence strongly suggests that those given the ICD-9 code 125.1 had zoonotic Brugia spp. it is possible that some of these cases represented B. malayi cases instead. Although it is impossible to discern the number of cases that have been miscoded, the estimated error rate for misdiagnosis is 20%.45–47 Given these limitations, further investigation is required to confirm the true case rates of lymphatic filariasis.

CONCLUSION

Filariasis is a mosquito-borne parasitic infection caused commonly by W. bancrofti and B. malayi in tropical developing countries. It is relatively rare in the United States with only around 58 admissions a year. Most patients with lymphatic filariasis in the United States are Caucasian, male, between 60 and 80 years old, and located on the eastern seaboard. We describe a patient without a travel history who presents with a 1-year history of cervical lymphatic filariasis who underwent surgical excision. Our data establishes filariasis as a rare but contributory infection in patients presenting with chronic lymphadenopathy in the United States.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Richard Bradbury, LeAnne Fox, Christine Dubray, and the Parasite Diagnostics and Biology Laboratory at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, GA); Thomas B. Nutman at the National Institutes of Health’s Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases (Bethesda, MD); and Yuxiang Ma, Medical Director of Microbiology at Signature Healthcare Brockton Hospital (Brockton, MA) for their valuable insight.

Disclaimer: Presented at the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Annual Meeting, Sept. 10–13, 2017, Chicago, IL. Under consideration for publication by American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Orihel TC, Eberhard ML, 1998. Zoonotic filariasis. Clin Microbiol Rev 11: 366–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor MJ, Hoerauf A, Bockarie M, 2010. Lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis. Lancet 376: 1175–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michael E, Bundy DA, 1997. Global mapping of lymphatic filariasis. Parasitol Today 13: 472–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramaiah KD, Ottesen EA, 2014. Progress and impact of 13 years of the global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis on reducing the burden of filarial disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8: e3319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization , 2016. Weekly Epidemiological Record, No. 39, Vol. 91, 441–460. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baird JK, Alpert LI, Friedman R, Schraft WC, Connor DH, 1986. North American brugian filariasis: report of nine infections of humans. Am J Trop Med Hyg 35: 1205–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elenitoba-Johnson KS, Eberhard ML, Dauphinais RM, Lammie PJ, Khorsand J, 1996. Zoonotic brugian lymphadenitis. An unusual case with florid monocytoid B-cell proliferation. Am J Clin Pathol 105: 384–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paniz-Mondolfi AE, Garate T, Stavropoulos C, Fan W, Gonzalez LM, Eberhard M, Kimmelstiel F, Sordillo EM, 2014. Zoonotic filariasis caused by novel Brugia sp. nematode, United States, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis 20: 1248–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez MT, Bush LM, Perdomo T, 2006. A 32-year-old immunocompetent man with submandibular lymphadenopathy. Lab Med 37: 619–622. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eberhard ML, Telford SR, 3rd, Spielman A, 1991. A Brugia species infecting rabbits in the northeastern United States. J Parasitol 77: 796–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beaver PC, Orihel TC, 1965. Human infection with filariae of animals in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg 14: 1010–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eberhard ML, DeMeester LJ, Martin BW, Lammie PJ, 1993. Zoonotic Brugia infection in western Michigan. Am J Surg Pathol 17: 1058–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutierrez Y, Petras RE, 1982. Brugia infection in northern Ohio. Am J Trop Med Hyg 31: 1128–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orihel TC, Beaver PC, 1989. Zoonotic Brugia infections in North and South America. Am J Trop Med Hyg 40: 638–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS), 1988–2015. HCUP, ed. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- 16.Ahn PJ, Bertagnolli R, Fraser SL, Freeman JH, 2005. Distended thoracic duct and diffuse lymphangiectasia caused by bancroftian filariasis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 185: 1011–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schick C, Thalhammer A, Balzer JO, Abolmaali N, Vogl TJ, 2002. Cystic lymph node enlargement of the neck: filariasis as a rare differential diagnosis in MRI. Eur Radiol 12: 2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaid SJ, Luthra A, Karnik S, Ahuja AT, 2011. Facial wrigglies: live extralymphatic filarial infestation in subcutaneous tissues of the head and neck. Br J Radiol 84: e126–e129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ottesen EA, Duke BO, Karam M, Behbehani K, 1997. Strategies and tools for the control/elimination of lymphatic filariasis. Bull World Health Organ 75: 491–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dey P, Radhika S, Jain A, 1993. Microfilariae of Wuchereria bancrofti in a lymph node aspirate. A case report. Acta Cytol 37: 745–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jindal A, Sukheeja D, Midya M, 2014. Cervical lymphadenopathy in a child—an unusual presentation of filariasis. Int J Sci Res Publ 4: 2250. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lalitha P, Eswaran D, Gnanasekar M, Rao KVN, Narayanan RB, Scott A, Nutman T, Kaliraj P, 2002. Development of antigen detection ELISA for the diagnosis of brugian and bancroftian filariasis using antibodies to recombinant filarial antigens Bm‐SXP‐1 and Wb‐SXP‐1. Microbiol Immunol 46: 327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer P, Boakye D, Hamburger J, 2003. Polymerase chain reaction-based detection of lymphatic filariasis. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl) 192: 3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goel TC, Goel A, 2016. Treatment and prognosis. Goel TC, Goel A, eds. Lymphatic Filariasis. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kazura J, Greenberg J, Perry R, Weil G, Day K, Alpers M, 1993. Comparison of single-dose diethylcarbamazine and ivermectin for treatment of bancroftian filariasis in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg 49: 804–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bockarie MJ, Alexander NDE, Hyun P, Dimber Z, Bockarie F, Ibam E, Alpers MP, Kazura JW, 1998. Randomised community-based trial of annual single-dose diethylcarbamazine with or without ivermectin against Wuchereria bancrofti infection in human beings and mosquitoes. Lancet 351: 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dreyer G, et al. 1995. Treatment of bancroftian filariasis in Recife, Brazil: a two-year comparative study of the efficacy of single treatments with ivermectin or diethylcarbamazine. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 89: 98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goel TC, Goel A, 2016. Antifilarial drugs. Goel TC, Goel A, eds. Lymphatic Filariasis. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ottesen EA, Vijayasekaran V, Kumaraswami V, Perumal Pillai SV, Sadanandam A, Frederick S, Prabhakar R, Tripathy SP, 1990. A controlled trial of ivermectin and diethylcarbamazine in lymphatic filariasis. N Engl J Med 322: 1113–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greene BM, et al. 1985. Comparison of ivermectin and diethylcarbamazine in the treatment of onchocerciasis. N Engl J Med 313: 133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herrick JA, et al. 2017. Posttreatment reactions after single-dose diethylcarbamazine or ivermectin in subjects with Loa loa infection. Clin Infect Dis 64: 1017–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardon J, Gardon-Wendel N, Demanga N, Kamgno J, Chippaux JP, Boussinesq M, 1997. Serious reactions after mass treatment of onchocerciasis with ivermectin in an area endemic for Loa loa infection. Lancet 350: 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Figueredo-Silva J, Dreyer G, Guimaraes K, Brandt C, Medeiros Z, 1994. Bancroftian lymphadenopathy: absence of eosinophils in tissues despite peripheral blood hypereosinophilia. J Trop Med Hyg 97: 55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jungmann P, Figueredo-Silva J, 1989. Bancroftian filariasis in the metropolitan area of Recife (Pernambuco State, Brazil): clinical aspects in histologically diagnosed cases. Braz J Med Biol Res 22: 687–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witt C, Ottesen EA, 2001. Lymphatic filariasis: an infection of childhood. Trop Med Int Health 6: 582–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cerda JR, Buttke DE, Ballweber LR, 2018. Echinococcus spp. tapeworms in North America. Emerg Infect Dis 24: 230–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Keefe KA, Eberhard ML, Shafir SC, Wilkins P, Ash LR, Sorvillo FJ, 2015. Cysticercosis-related hospitalizations in the United States, 1998–2011. Am J Trop Med Hyg 92: 354–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brabin L, 1990. Sex differentials in susceptibility to lymphatic filariasis and implications for maternal child immunity. Epidemiol Infect 105: 335–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO , 1992. Lymphatic Filariasis: The Disease and Its Control, Fifth Report of the WHO Expert Committee on Filariasis [Meeting Held in Geneva from 1 to 8 October 1991]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [PubMed]

- 40.Newton WL, Wright WH, Pratt I, 1945. Experiments to determine potential mosquito vectors of Wuchereria bancrofti in the continental United States 1. Am J Trop Med 25: 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beaver PC, Wong MM, 1988. Brugia sp. from a domestic cat in California. Proc Helminthol Soc Wash 55: 111–113. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chansiri K, Tejangkura T, Kwaosak P, Sarataphan N, Phantana S, Sukhumsirichart W, 2002. PCR based method for identification of zoonostic Brugia malayi microfilariae in domestic cats. Mol Cell Probes 16: 129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kanjanopas K, Choochote W, Jitpakdi A, Suvannadabba S, Loymak S, Chungpivat S, Nithiuthai S, 2001. Brugia malayi in a naturally infected cat from Narathiwat Province, southern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 32: 585–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomoen W, 2005. Susceptibility of Mansonia uniformis to Brugia malayi microfilariae from infected domestic cat. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 36: 434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amy Y, Quan H, McRae AD, Wagner GO, Hill MD, Coutts SB, 2017. A cohort study on physician documentation and the accuracy of administrative data coding to improve passive surveillance of transient ischaemic attacks. BMJ Open 7: e015234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stausberg J, Lehmann N, Kaczmarek D, Stein M, 2008. Reliability of diagnoses coding with ICD-10. Int J Med Inform 77: 50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gologorsky Y, Knightly JJ, Lu Y, Chi JH, Groff MW, 2014. Improving discharge data fidelity for use in large administrative databases. Neurosurg Focus 36: E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]