Abstract.

Delay in diagnosis and treatment worsens the disease and clinical outcomes, which further enhances transmission of tuberculosis (TB) in the community. Therefore, this study aims to assess treatment delay and its associated factors among pulmonary TB patients in Pakistan. A cross-sectional study was conducted among 269 pulmonary TB patients in the district. Binary and multivariate logistic regressions were used to explore the factors associated with delay in TB treatment. Results reveal that most patients were from low socioeconomic backgrounds. For example, 74.7% were living in kacha houses, 54.7% were from lowest the income group (< 250 US$/month), 60.2% married, 54.3% illiterate, 62.5% rural, 56.1% had no house ownership, and 56.5% had insufficient income for daily family expenditures. Significant delays were revealed by this study: 160 patients had experienced a delay of more than 4 weeks, whereas the median delay was 5 weeks. Results show that the most important reason for patient delay was low income and poverty (42.0%) followed by unaware of TB center (41.6), stigma (felt ashamed = 38.7%), and treatment from local traditional healers. Old age (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 6.6; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.63–26.95); and rural areas patients (AOR = 2.1; 95% CI = 1.15–3.71) were more likely to have experienced delay. However, the higher income and sufficient income category (AOR = 0.5; 95% CI = 0.31–0.95) were associated factors and less likely to experience delay in patient treatment. Integrative prevention interventions, such as those involving community leaders, health extension workers such as lady health workers, and specialized TB centers, would help to reduce delay and expand access to TB-care facilities.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major public health problem worldwide. Pakistan is one of the highest burden TB countries in the world, with an annual case incidence of 500,000,1 which makes it one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, Pakistan contributes about 44% of the TB burden in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR)2 and accounted for 80% of the World Health Organization EMRs Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis burden.1

Directly observed treatment short courses (DOTS) is the foremost strategy for prevention and control of TB around the world.3 In Pakistan, the DOTS program was adopted as the national strategy in 2000. Later, as a part of primary health care, it was expanded to all public health facilities. The program was successful in achieving 70% case detection and 85% positive treatment outcome of the global target set by Stop TB Partnership.4 Pakistan’s ministry of health declared TB a national public health emergency in 2001 under the “Islamabad Declaration”.5 The National TB Control Program (NTP) officially achieved a TB case detection rate of 64% in 2011, primarily because of the expansion of DOTS.6 This cure rate increased from 64% in 2003 to 74% in 2009. Countrywide implementation of DOTS has been strengthened, supporting a network of 11,445 diagnostic centers and more than 5,000 treatment centers in 134 districts of Pakistan. Despite many achievements under the DOTS program, the bulk of patients are still not picked by community health providers, nor are they properly observed.7 Thus, TB is still a huge burden among the chronic diseases prevailing in Pakistan.

Despite the high level of treatment availability for decades and the adoption of DOTS by the Pakistan’s NTP since 1995,5 the latest statistics show no significant progress in TB control.8 Delay in seeking treatment due to lack of awareness or poor access to health services results in increase rates of transmission in the community and increase in disease prevalence. For instance, lack of knowledge about the disease9,10 and stigmatization9,11 cause the underutilization of services, delay in seeking diagnosis, and poor treatment compliance. Severe isolation and other social consequences are described as important factors in causing delay in TB diagnosis, especially among women. Patients often hide their TB from other members of the community.12

Previous studies have proved that treatment delay is the main hindering factor in the control of TB. For example, De Almeida et al.,13 Ward et al.,14 and Yimer et al.15 revealed that a single TB patient who remains untreated can infect from 10 to 15 people every year. Moreover, delay in TB treatment may result in further complications and poor health, thus increasing the risk of mortality.14,15 In addition, delays in diagnosis and treatment may worsen the disease, clinical outcomes, and transmission of TB in the community.16 Researchers from both developed and developing countries have reported delays in the TB diagnosis. For instance, delays of 8.1 weeks were reported in New York,17 22 days in Spain,18 12 weeks in Botswana and Ethiopia,15,19 26 weeks in Tanzania,20 62 days in India,21 60 days in Bangladesh,21 and 71 days in China.23

In Pakistan, where incidence, prevalence, and high transmission of TB are crucial, limited studies are available on TB patients’ delay in general and on pulmonary TB patients in particular. Hence, this study is designed to assess the delay in treatment of TB and determine the important factors associated with it.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants and setting.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province was purposively selected because of its high prevalence of TB, where approximately 58,449 new cases of TB were reported in 2014.24,25 In response to this high prevalence, the provincial government considered it a serious public health problem. Consequently, an act was passed in 2016 from the provincial assembly known as “The KP TB Notification Bill, 2016” that categorizes TB as a disease to be notified by all involved persons, including medical practitioners, private and government clinics, and also community leaders.26 Likewise, Mardan district was selected among 26 districts of the province because it has the second highest DOTS population after Peshawar. The total population of the district is 1.46 million, of which 0.75 million are male and 0.71 million female.27 A total of 5,624 TB patients were registered at 11 TB centers and private clinics in the district in 2016,28 as shown in Figure 1. Out of the total patients in the whole year, 3,050 were registered in the third and fourth quarter. Excluding 783 children and 413 old age patients, 1,854 adult patients remained . Purposively, we targeted adult patients because of their ability to interview them at the health center. Furthermore, from the total adult patients, we obtained 1,019 adult pulmonary patients (53% female and 47% male) and used the suggested formula of Naing et al.29 (Eq. 1) to calculate the sample size. As a result, a 280 sample size was calculated.

| (1) |

where = sample size, = total number TB adult patients (1,019), = confidence level (at 95% level, = 1.96), = estimated population proportion (0.55, this maximizes the sample size suggested by Lwanga and Lemeshow,30 = desired error set as 5%.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of sampling.

Total sample size was proportionally allocated among male and female participants: 132 male patients and 148 female patients. Finally, patients were randomly selected who were under treatment for at least 1 month in the last two quarters of year 2016. Data were collected over a duration of 3 months, from November 2016 to January 2017. However, in the third month of data collection, because of several sociocultural constraints and incomplete questionnaire, our total sample was 269 and consisted of 130 male and 139 female respondents.

Ethical considerations.

The study was approved by the Research Ethical Review Committee of the Asian Institute of Technology (Thailand), reference no. RERC 2017/001. Furthermore, the data were collected only after receiving written consent from the respondents. Respondents’ personal information, such as names, computerized national identity card numbers, telephone numbers, and signed agreements were locked in the first author’s office.

Operational definitions.

The term “treatment delay” refers to the total delay, for any reason, that affects a patient in the health-care system. Patient delay is defined as follows: the period between the onset of TB symptoms and contact with a health center. This study considered patient delay when the treatment delay was > 4 weeks (≈30 days). Several studies have used delay in treatment > 30 days as patient delay. For example, Takarinda et al.31 and Finnie et al.32 used delay in treatment > 30 days. However, during the questionnaire pretest, we changed the questions regarding the delay in days. It was difficult for patients to remember how long they had delayed in days; however, it was easier for them to remember in weeks. We therefore recorded their responses in weeks. In addition, contact with health centers in this study means consulting specialized TB centers or private TB clinics and excludes the private practitioners and pharmacists who do not provide TB treatment. Moreover, TB onset symptoms refer to patients experiencing cough for more than 3 weeks,14 weight loss, fever, hemoptysis, night sweats, and fatigue.31

Data analysis.

The data were entered and analyzed through SPSS-23 version (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Considering the nature of the study variables, we used the χ2 test for comparison of the patients’ groups. The confidence interval of 95% (95% confidence interval [CI]) for socioeconomic factors was calculated using Microsoft Office Excel 2016. The unadjusted odds ratios of 95% CI were calculated through binary logistic regression. For adjusted odds ratio (AOR), we used a multivariate logistic regression model. In multivariate logistic regression, we included variables with a significance level P ≤ 0.25.33,34

RESULTS

Socioeconomic characteristics of patients.

A total of 269 pulmonary TB patients were interviewed at TB clinics in Mardan district, 51.7% were males. Most patients were young: 15–20 years old (23.4%), 21–30 years (32.7%), and 31–40 years old (20.10%). Most respondents were married (60.2%), illiterate (54.3%), and most of them had families comprising 5–10 members. Most patients (62.5%) were from rural areas and living in poor dwellings. As shown by in Table 1, 74.7% live in kacha houses† (low quality houses), and most did not own their house. Only few patients (25.28%) were living in pacca‡ houses (high quality houses). Furthermore, 54.7% were from the lowest income category (< 250 US$ monthly household’s income). Of total patients, 56.5% declared that their income was not sufficient to finance family expenditures, and most of them were laborers or in the agriculture industry, who constituted the main source of household’s income (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socioeconomic characteristics of patients (N = 269)

| Socioeconomic characteristics | n (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 15–20 | 63 (23.4) | (18.4–28.5) |

| 21–30 | 88 (32.7) | (27.1–38.3) |

| 31–40 | 54 (20.1) | (15.3–24.9) |

| 41–50 | 45 (16.7) | (12.3–21.1) |

| 51–60 | 19 (7.1) | (4.0–10.1) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 139 (51.7) | (45.7–57.6) |

| Male | 130 (48.3) | (42.4–54.3) |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 91 (33.8) | (28.2–39.5) |

| Married | 162 (60.2) | (54.4–66.1) |

| Widowed | 16 (6.0) | (3.1–8.8) |

| Household size | ||

| 1–5 | 72 (26.8) | (21.5–32.1) |

| 5–10 | 147 (54.7) | (48.7–60.6) |

| 10–15 | 32 (11.9) | (8.0–15.8) |

| > 15 | 18 (6.7) | (3.7–9.7) |

| Literacy | ||

| Illiterate | 146 (54.3) | (48.3–60.2) |

| Literate | 123 (45.7) | (39.8–51.7) |

| Location | ||

| Urban | 101 (37.6) | (31.8–43.3) |

| Rural | 168 (62.5) | (56.7–68.2) |

| House type | ||

| Low quality | 201 (74.7) | (69.5–79.9) |

| High quality | 68 (25.3) | (20.1–30.5) |

| House ownership | ||

| Yes | 118 (43.9) | (37.9–49.8) |

| No | 151 (56.13) | (50.2–62.1) |

| Monthly income (US$) | ||

| < 250 | 147 (54.7) | (84.7–60.6) |

| 250–500 | 83 (30.9) | (25.3–36.4) |

| 500–750 | 23 (8.6) | (5.3–11.9) |

| > 750 | 16 (6.0) | (3.1–8.8) |

| Income sufficiency | ||

| Yes | 117 (43.5) | (37.6–49.4) |

| No | 152 (56.5) | (50.6–62.4) |

| Source of income | ||

| Agriculture | 77 (28.6) | (23.2–43.0) |

| Trader | 41 (15.2) | (10.9–19.5) |

| Laborer | 92 (34.2) | (28.5–39.9) |

| Servant | 33 (12.3) | (8.3–16.2) |

| Others | 26 (9.7) | (6.1–13.2) |

CI = confidence interval.

Proportion of patients in different ranges of treatment delay.

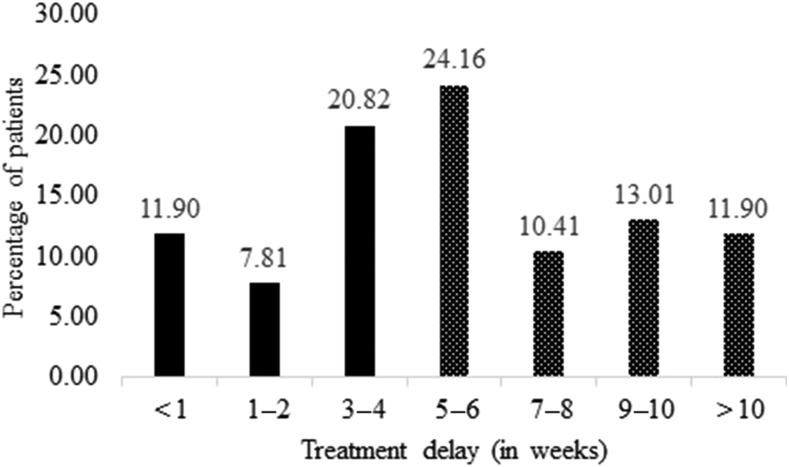

Delay was distributed into seven groups, as shown in Figure 2. The highest number (24.2%) of patients were in the range 5–6 weeks, followed by 20.8% in the range 3–4 weeks. Median patient delay was 5 weeks and average delay was 6 weeks. A delay in treatment of more than 4 weeks was considered as cut point for analysis in this study, which occurred among almost 60% of total patients.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients in different ranges of treatment delay. TB = tuberculosis.

Reasons for patient delay in TB treatment.

Table 2 shows the various reasons for patient delay. We asked the patients closed- and open-ended multiple-choice questions for the reasons they had delayed. We were interested to know why the patients were still delaying treatment even on the appearance of onset TB symptoms, such as weight loss, fever, hemoptysis, night sweats, and fatigue. Furthermore, during the analysis we ranked it on the base of the higher proportion of responses. Results show that the most important reason for patient delay is low income and poverty (42.01%) followed by not being aware of the TB center (41.64%). The third most important reason is felt ashamed, a proxy for stigma (felt ashamed = 38.66%), whereas 31.6% contacted traditional healers. However, the lowest was the high treatment cost of TB and lack of gender facilities in the health centers.

Table 2.

Reasons for patient delay

| Reasons for delay | n | % | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low income and poverty | 113 | 42.0 | 1 |

| Not aware of the TB center | 112 | 41.6 | 2 |

| Felt ashamed (stigma) | 104 | 38.7 | 3 |

| Traditional healers | 85 | 31.6 | 4 |

| Religious leaders | 79 | 29.4 | 5 |

| Busy doing domestic work | 77 | 28.6 | 6 |

| TB center is too far | 58 | 21.6 | 7 |

| Community exclusion | 42 | 15.6 | 8 |

| High cost of transportation | 39 | 14.5 | 9 |

| Lack of cooperation from household | 35 | 13.0 | 10 |

| Substandard care for the poor | 28 | 10.4 | 11 |

| Lack of gender facilities | 26 | 9.7 | 12 |

| High treatment cost | 22 | 8.2 | 13 |

TB = tuberculosis.

Delay and associated factors.

The delay in weeks was divided into two groups: patients with delay (> 4 weeks) and with no delay (≤ 4 weeks). The chi-square test was used to explore the differences between patients’ groups along with socioeconomic factors (Table 3). This investigation provided the ground for further analysis, helped to decide which factors were important enough to be included in the subsequent regression analysis. Results reveal that delay among females was higher (71.90%) than among their male counterparts (46.20%), and the difference was significant at P ≤ 0.01. Likewise, of total rural patients, 67.66% delayed their treatment compared with urban patients (46.08%). The difference was significant at P ≤ 0.01. In addition, patients from the lower income group had more delay (68.71%) compared with other groups and was statistically significant. Main source of income as a factor of delay shows that most of the patients from agricultural households and laborers (76.62% and 61.96%, respectively) delayed treatment in comparison with other groups. The difference was highly significant at P ≤ 0.01.

Table 3.

Association between delay in treatment of tuberculosis and socioeconomic characteristics of patients (N = 269)

| Socioeconomic characteristics | Patients without delay in treatment n (%) | Patients with delay in treatment n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 15–20 | 32 (50.8) | 31 (49.2) | 0.071 |

| 21–30 | 36 (40.9) | 52 (59.1) | |

| 31–40 | 24 (44.4) | 30 (55.6) | |

| 41–50 | 13 (29.0) | 32 (71.0) | |

| 51–60 | 4 (21.1) | 15 (79.0) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 39 (21.1) | 100 (71.9) | 0.000** |

| Male | 70 (53.8) | 60 (46.2) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Unmarried | 32 (35.2) | 59 (64.8) | 0.264 |

| Married | 72 (44.4) | 90 (55.6) | |

| Widowed | 5 (31.3) | 11 (68.7) | |

| Household size | |||

| 1–5 | 28 (39.0) | 44 (61.0) | 0.585 |

| 5–10 | 64 (43.5) | 83 (56.5) | |

| 10–15 | 12 (37.5) | 20 (62.5) | |

| > 15 | 5 (27.8) | 13 (72.2) | |

| Literacy | |||

| Illiterate | 60 (41.1) | 86 (58.9) | 0.901 |

| Literate | 49 (39.8) | 74 (60.2) | |

| Location | |||

| Urban | 55 (53.9) | 47 (46.1) | 0.001** |

| Rural | 54 (32.3) | 113 (67.7) | |

| House type | |||

| Low quality | 80 (39.8) | 121 (60.2) | 0.679 |

| High quality | 29 (42.7) | 39 (57.3) | |

| House ownership | |||

| Yes | 53 (44.9) | 65 (55.1) | 0.194 |

| No | 56 (37.1) | 95 (62.9) | |

| Monthly income | |||

| < 250 | 46 (31.3) | 101 (68.7) | 0.002** |

| 250–500 | 38 (46.3) | 44 (53.7) | |

| 500–750 | 14 (58.3) | 10 (41.7) | |

| > 750 | 11 (68.8) | 5 (31.2) | |

| Income sufficiency | |||

| Yes | 60 (51.3) | 57 (48.7) | 0.002** |

| No | 49 (32.2) | 103 (67.8) | |

| Source of income | |||

| Agriculture | 18 (23.4) | 59 (76.6) | 0.000** |

| Trader | 22 (53.7) | 19 (46.3) | |

| Laborer | 35 (38.0) | 57 (62.0) | |

| Servant | 21 (63.6) | 12 (36.4) | |

| Others | 13 (50.0) | 13 (50.0) | |

P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01.

Results of regression model.

Regression analysis was performed by including variables that had a significance at P ≤ 0.25. Our dependent variable was dichotomous in nature; 0 = no treatment delay and 1 = treatment delay. Results show that the elderly (51–60 years) were more likely (AOR = 6.63; 95% CI = 1.63–26.95) to experience delay in treatment. Further analysis shows that female patients were more likely (AOR = 2.21; 95% CI = 1.22–3.97) to experience delay in treatment than males. Likewise, the likelihood of treatment delay among the patients from rural areas was higher than that from urban areas, confirmed by both binary logistic and multivariate logistic regression results (AOR = 2.06; 95% CI = 1.15–3.71). As in the aforementioned section, low income and poverty were the highest ranked reasons for treatment delay, as shown in Table 4. The results of binary logistic regression show that patients from the higher income group were less likely to experience delayed treatment. However, the multivariate logistic results were not significant at P ≤ 0.05. Likewise, patients who had sufficient income were less likely (AOR = 0.54; 95% CI = 0.31–0.95) to experience delay in treatment.

Table 4.

Odds ratios of factors associated with delay in treatment

| Variables | UOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 15–20 | Ref | Ref |

| 21–30 | 1.5 (0.78–2.86) | 2.0 (0.92–4.39) |

| 31–40 | 1.3 (0.62–2.68) | 1.5 (0.65–3.50) |

| 41–50 | 2.5 (1.13–5.72)* | 1.7 (0.69–4.18) |

| 51–60 | 3.9 (1.16–12.96)* | 6.6 (1.63–26.95)** |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 3.0 (1.80–4.96)** | 2.2 (1.22–3.97)** |

| Location | ||

| Urban | Ref | Ref |

| Rural | 2.5 (1.48–4.06)** | 2.1 (1.15–3.71)* |

| House ownership | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.4 (0.85–2.26) | 0.9 (0.49–1.52) |

| Monthly income | ||

| < 250 | Ref | Ref |

| 250–500 | 0.5 (0.30–0.92)* | 0.7 (0.36–1.23) |

| 500–750 | 0.3 (0.13–0.79)** | 0.4 (0.14–1.03) |

| > 750 | 0.2 (0.07–0.63)* | 0.3 (0.09–1.10) |

| Income sufficiency | ||

| No | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 0.5 (0.27–0.74)** | 0.5 (0.31–0.95)* |

| Sources of income | ||

| Others | Ref | Ref |

| Agriculture | 3.3 (1.29–8.33)** | 1.5 (0.51–4.25) |

| Trader | 0.9 (0.32–2.31) | 0.5 (0.17–1.67) |

| Laborer | 1.6 (0.68–3.91) | 0.9 (0.32–2.39) |

| Servant | 0.6 (0.20–1.63) | 0.4 (0.12–1.24) |

AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; UOR = unadjusted odds ratio.

P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Results reveal that there is a significant delay from the onset of symptoms of TB to contact with TB centers. Of the total patients, 60% delayed treatment for more than 4 weeks, whereas the mean delay was 6 weeks. This implies that a substantial proportion of patients in the study area did not go to TB centers at the early stages of TB. This was an alarming situation, as this group of patients were contagious. The findings of this study are different from Saqib et al.35 They reported 56 days (8 weeks) delay in TB treatment from an eastern region of Pakistan. However, our study was conducted in a different province, in a western region of the country, where the provincial government has been taking serious initiatives in TB detection. The findings show that the provincial government’s new act on TB, passed from provincial assembly in 2016, is showing significant results. Therefore, the delay reported by this study is slightly lower than that of the previous study conducted in a western part of the country.

Patients’ socioeconomic characteristics play an important role in their treatment delay. For instance, age,13,31,33,36 sex,2,31,33,34,36 marital status,33,34 residence,31,36 educational status,31,34 monthly income,13 occupational status, family size, stigma,34 distance to health facility,31,34 and knowledge about TB34 were significant factors associated with treatment delay.

Moreover, findings of the study show that most of the patients registered at health centers were in the young and productive age range. This implies that in Pakistan, TB is targeting the most productive age group of people. Our results are consistent with those of Gupta et al.37 They reported that in South India most patients were from 21 to 40 years of age. In addition, our participants were illiterate, from rural areas, and were from very poor economic strata. Findings of this study confirm the results of Shafqaat and Jamil,38 who revealed that most TB patients were illiterate in Punjab province of Pakistan. This implies that in Pakistan, TB patients are mostly illiterate or have a low level of education. Poverty and low income are the root causes of TB.39–41 A study conducted by Shafqaat and Jamil38 reported that most TB patients (60%) were living in extreme poverty in Pakistan. In addition, our study confirms the findings of Craig et al.11 They revealed that in the United Kingdom, 70% of TB patients were from 40% of the poorest areas, and were unemployed.

The study found that age was a very important factor associated with delay. Older patients had more delay than young. In light of the social context, men are the elders in the family and the sole bread winners. Their work kept them busy the whole day, whereas women were busy at household work. Therefore, the elders experienced more delay in treatment than the young. During our data collection, several patients reported that they were busy at work and had no time to see the doctor at the health center. The findings of the study are in agreement with Mesfin et al.42 and Lin et al.,36 studies from Northern Ethiopia and China, respectively, who reported higher delays in old age patients than young patients. However, our findings are dissimilar to those of Htike et al.,33 who conducted a study in Dhaka city of Bangladesh, and Saqib et al.35 from Punjab, Pakistan. They reported that patients of younger age experienced more treatment delay than older patients. This indicates that in our study most patients were living in rural areas and with less accessibility to health centers. Therefore, people of old age need a care taker to see doctors in the city, which caused a higher delay among them.

A previous study conducted in Pakistan showed that sex is strongly associated with delay in TB treatment.35 Our findings are similar to this study: females have greater delay than male patients. Many other studies have been conducted in different settings; for example, Needham et al.43 in urban areas of Zambia, Karim et al.22 in Bangladesh, and Lin et al.36 in China that revealed delay among females was longer than males. In addition, patients from rural settings have several problems that range from lack of provision of health facilities to roads and infrastructure. Logistic difficulties may be one reason why rural people from rural areas access care late in their disease course. Our findings also show that patients from rural areas had longer delay than those from urban areas. Studies from other countries have shown that rural residence is associated with patient delay in treatment. For instance, Lienhardt et al.44 conducted a study in Gambia, sub-Saharan Africa; Pronyk et al.45 in rural areas of South Africa; Takarinda et al.31 in Zimbabwe; and Lin et al.36 in China that revealed that patients from rural areas experienced higher delay than urban patients.

Data analysis showed that most patients were of low economic status and had insufficient income to finance their family’s daily expenditures. Consequently, patients from the higher income group had a shorter delay compared with those from lower economic statuses. Unlike the findings of Almeida et al.46—study from Brazil, the reasons mentioned in our analysis and the regression results show that poverty and low income had a strong association with treatment delay among the patients.

Other findings show that TB-associated stigma is one of the most important factors associated with delay in treatment. Highly stigmatized patients are more likely to delay treatment in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.34 It implies that TB associated stigma hinders patients from seeking treatment. During the interviews, many of the female patients expressed that TB diagnosis not only limits their own (patients’) chance of marrying but also causes embarrassment for the whole family. Therefore, most patients were not going to see TB specialist doctors. According to the World Health Organization47 report, stigma is one of the most important determinants in the health-seeking behavior of TB patients in Pakistan. Our findings are similar to those for other countries, such as Yemen, Syria, and Somalia.47

Patients were also not aware of the TB treatment facilities available at health centers. In addition, they had no knowledge that TB is treated free of cost under the DOTS program. The main reason for patients’ unawareness was that no local community or health extension workers, such as lady health workers at basic health units (BHUs), were involved in the program. In addition, the role of print and electronic media about TB awareness was negligible. All treatment facilities were at the large hospitals and rural health centers (upper tier compared with BHUs). Therefore, patients were consulting traditional healers and non-professional local health practitioners at the onset of symptoms. This caused delay among the patients in rural areas and women in particular, as they always remain at home and need a male supporter to see the doctors in city centers. Based on findings of the study, mass information campaigns are necessary in Pakistan. For example, posters, multimedia presentations, campaign through local radio channels, newspaper, or a script for television as a public service announcements, and involving religious and community leaders in TB awareness can help to reduce treatment delay among the TB patients in Pakistan.

Weaknesses and strengths.

This study has some weaknesses. First, as mentioned in previous sections, we conducted this study in all TB centers located in Mardan district. The results of treatment delay may be different in other parts of the country. Second, we measured the delay in weeks, which may not represent the actual days of delay. Third, we were not able to trace the patients who were lost during follow-up because of limited time and other financial constraints. Fourth, the study did not cover the extra pulmonary TB patients’ treatment delay in the study area. It might show different delay among the patients. Last, the data about bacteriological status of the patients, disease severity, and response to treatment was in computer section in the district TB office and not finalized. Therefore, the study did not incorporate this information in the analysis.

The study contributes significantly to the literature for different reasons. First, our study provides a concrete analysis of delay in a specific region of Pakistan. Therefore, the findings may help policy makers to address the problems in TB-care delivery in accordance with the social context. Second, this is the first attempt that a study has highlighted patient delay in a western province of the country. Third, for the first time this study has ranked the reasons for which patients delay treatment. Last, the study provides recommendations for reducing TB patients’ delay in the context of Pakistan.

CONCLUSION

In general, the study showed significant delay among pulmonary TB patients in the study area. Females and patients from rural areas and of lower socioeconomic status experienced high delay in treatment. Poverty and low income, unawareness of TB centers, stigma, and consulting local healers and nonprofessional practitioners were common reasons for delay among patients. Based on the findings of this study, it is suggested that an active case detection strategy should be adopted to screen family members and the community by involving local village leaders and lady health workers. It is also important to involve health workers in disseminating knowledge on the causes of TB, its curability, and treatment facilities in rural areas. Health education seminars are needed to raise awareness and reduce TB-associated stigma among the people. This approach should target the family as a whole and raise awareness about the high rates of TB in the community (particularly among young women) and it is easy. To explore the root causes of high TB prevalence in the study area, it is essential to conduct a study in the future to include those patients who were lost after referral. Furthermore, the future study may investigate bacteriological status of the patients, disease severity and their response to treatment. This will help policy makers see the urgent need for awareness raising, enhanced case finding, and contact management to stop ongoing TB transmission.

Acknowledgments:

We extend sincere thanks to the district TB Program officials and staff for their support during data collection. We are grateful to all study participants who spared their time for interviews. The principal author accredits the support of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan for the award of a Ph.D. scholarship. The authors also extend thanks to Howard Goldman for proof reading of the manuscript. The data and materials used in this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Footnotes

Kacha houses are made from low quality materials such as mud, straw, wood, and dry leaves.

Pacca houses are made from substantial high quality materials such as brick, cement, stone, and concrete.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization , 2015. Glocal Tuberculosis Report Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/191102/1/9789241565059_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed February 2, 2016.

- 2.World Health Organization , 2009. Global Tuberculosis Control Epidemiology Strategy Financing Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44241/1/9789241598866_eng.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2016.

- 3.DeRiemer K, García-García L, Bobadilla-del-Valle M, Palacios-Martínez M, Martínez-Gamboa A, Small PM, Sifuentes-Osornio J, Ponce-de-León A, 2005. Does DOTS work in populations with drug-resistant tuberculosis? Lancet 365: 1239–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vermund SH, Altaf A, Samo RN, Khanani R, Baloch N, Qadeer E, Shah SA, 2009. Tuberculosis in Pakistan: a decade of progress, a future of challenge. J Pak Med Assoc 59: 1–8.19213366 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metzger P, Baloch N, Kazi G, Bile K, 2010. Tuberculosis control in Pakistan: reviewing a decade of success and challenges. East Mediterr Health J 16: 47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fatima R, Harris R, Enarson D, Hinderaker S, Qadeer E, Ali K, Bassilli A, 2014. Estimating tuberculosis burden and case detection in Pakistan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 18: 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iram S, Ali S, Khan SA, Abbasi MA, Anwar SA, Fatima F, 2011. TB dots strategy in district Rawalpindi: results and lessons. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 23: 85–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haider BA, Akhtar S, Hatcher J, 2013. Daily contact with a patient and poor housing affordability as determinants of pulmonary tuberculosis in urban Pakistan. Int J Mycobacteriol 2: 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mushtaq MU, Shahid U, Abdullah HM, Saeed A, Omer F, Shad MA, Akram J, 2011. Urban-rural inequities in knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding tuberculosis in two districts of Pakistan’s Punjab province. Int J Equity Health 10: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hino P, Takahashi RF, Bertolozzi MR, Egry EY, 2011. The health needs and vulnerabilities of tuberculosis patients according to the accessibility, attachment and adherence dimensions. Rev Esc Enferm USP 45: 1656–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig G, Daftary A, Engel N, O’Driscoll S, Ioannaki A, 2017. Tuberculosis stigma as a social determinant of health: a systematic mapping review of research in low incidence countries. Int J Infect Dis 56: 90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baral SC, Karki DK, Newell JN, 2007. Causes of stigma and discrimination associated with tuberculosis in Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 7: 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Almeida CP, Skupien EC, Silva DR, 2015. Health care seeking behavior and patient delay in tuberculosis diagnosis. Cad Saude Publica 31: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward H, Marciniuk D, Pahwa P, Hoeppner V, 2004. Extent of pulmonary tuberculosis in patients diagnosed by active compared to passive case finding. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 8: 593–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yimer S, Bjune G, Alene G, 2005. Diagnostic and treatment delay among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 5: 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rifat M, Rusen I, Islam MA, Enarson D, Ahmed F, Ahmed S, Karim F, 2011. Why are tuberculosis patients not treated earlier? A study of informal health practitioners in Bangladesh. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 15: 647–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pirkis JE, Speed BR, Yung AP, Dunt DR, Maclntyre CR, Plant AJ, 1996. Time to initiation of anti-tuberculosis treatment. Tuber Lung Dis 77: 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diez M, et al. 2004. Determinants of patient delay among tuberculosis cases in Spain. Eur J Public Health 14: 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steen T, Mazonde G, 1998. Pulmonary tuberculosis in Kweneng District, Botswana: delays in diagnosis in 212 smear-positive patients. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2: 627–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wandwalo ER, Mørkve O, 2000. Delay in tuberculosis case-finding and treatment in Mwanza, Tanzania. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 4: 133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selvam JM, Wares F, Perumal M, Gopi P, Sudha G, Chandrasekaran V, Santha T, 2007. Health-seeking behaviour of new smear-positive TB patients under a DOTS programme in Tamil Nadu, India, 2003. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 11: 161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karim F, Islam MA, Chowdhury A, Johansson E, Diwan VK, 2007. Gender differences in delays in diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. Health Policy Plan 22: 329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin X, Chongsuvivatwong V, Geater A, Lijuan R, 2008. The effect of geographical distance on TB patient delays in a mountainous province of China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 12: 288–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saqib SE, Ahmad MM, Amezcua-Prieto C, 2018. Economic burden of tuberculosis and its coping mechanism at the household level in Pakistan. Soc Sci J, 10.1016/j.soscij.2018.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DHIS , 2014. Disease Pattern in Out Patient Department. Peshawar, Pakistan: District Health Information System, K.P.K. Department of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa , 2016. The KP Tuberculosis Notification Bill Available at: http://www.pakp.gov.pk/2013/bills/the-khyber-pakhtunkhwa-tuberculosis-notification-bill-2016/. Accessed April 23, 2017.

- 27.Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa , 2017. Mardan District Demographics (Census, 1998) Available at: http://kp.gov.pk/page/mardandistrictdemographics. Accessed March 2, 2017.

- 28.Distric TB Office Mardan , 2016. Consolidated Report: Consolidated Report of TB Reporting Centers. Mardan, Pakistan: District TB Office Mardan. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naing L, Winn T, Rusli B, 2006. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch Orofac Sci 1: 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lwanga SK, Lemeshow S, 1991. Sample Size Determination in Health Studies: A Practical Manual. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takarinda KC, Harries AD, Nyathi B, Ngwenya M, Mutasa-Apollo T, Sandy C, 2015. Tuberculosis treatment delays and associated factors within the Zimbabwe national tuberculosis programme. BMC Public Health 15: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finnie RK, Khoza LB, van den Borne B, Mabunda T, Abotchie P, Mullen PD, 2011. Factors associated with patient and health care system delay in diagnosis and treatment for TB in sub-Saharan African countries with high burdens of TB and HIV. Trop Med Int Health 16: 394–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Htike W, Islam M, Hasan M, Ferdous S, Rifat M, 2013. Factors associated with treatment delay among tuberculosis patients referred from a tertiary hospital in Dhaka city: a cross-sectional study. Public Health Action 3: 317–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adenager GS, Alemseged F, Asefa H, Gebremedhin AT, 2017. Factors associated with treatment delay among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in public and private health facilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Tuberc Res Treat 2017: 5120841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saqib MA, Awan IN, Rizvi SK, Shahzad MI, Mirza ZS, Tahseen S, Khan IH, Khanum A, 2011. Delay in diagnosis of tuberculosis in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. BMC Res Notes 4: 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin Y, et al. 2015. Patient delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in China: findings of case detection projects. Public Health Action 5: 65–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta S, Shenoy VP, Mukhopadhyay C, Bairy I, Muralidharan S, 2011. Role of risk factors and socio-economic status in pulmonary tuberculosis: a search for the root cause in patients in a tertiary care hospital, south India. Trop Med Int Health 16: 74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shafqaat M, Jamil S, 2012. The distribution of tuberculosis patients and associated socio economic risk factors for transmission of tuberculosis disease in Faisalabad city. Asian J Nat Appl Sci 1: 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oxlade O, Murray M, 2012. Tuberculosis and poverty: why are the poor at greater risk in India? PLoS One 7: e47533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creswell J, Jaramillo E, Lönnroth K, Weil D, Raviglione M, 2011. Tuberculosis and poverty: what is being done. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 15: 431–432 (Counterpoint). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hargreaves JR, Boccia D, Evans CA, Adato M, Petticrew M, Porter JD, 2011. The social determinants of tuberculosis: from evidence to action. Am J Public Health 101: 654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mesfin MM, Tasew TW, Tareke IG, Kifle YT, Karen WH, Richard MJ, 2005. Delays and care seeking behavior among tuberculosis patients in Tigray of northern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 19: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Needham DM, Foster SD, Tomlinson G, Godfrey‐Faussett P, 2001. Socio‐economic, gender and health services factors affecting diagnostic delay for tuberculosis patients in urban Zambia. Trop Med Int Health 6: 256–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lienhardt C, Rowley J, Manneh K, Lahai G, Needham D, Milligan P, McAdam K, 2001. Factors affecting time delay to treatment in a tuberculosis control programme in a sub-Saharan African country: the experience of The Gambia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 5: 233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pronyk P, Makhubele M, Hargreaves J, Tollman S, Hausler H, 2001. Assessing health seeking behaviour among tuberculosis patients in rural South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 5: 619–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Almeida CP, Skupien EC, Silva DR, 2015. Health care seeking behavior and patient delay in tuberculosis diagnosis. Cad Saude Publica 31: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization , 2006. Diagnostic and Treatment Delay in Tuberculosis. An In-Depth Analysis of the Health-Seeking Behaviour of Patients and Health System Response in Seven Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: http://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/dsa710.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2017.