Abstract

Objective:

Arterial calcification is associated with an increased risk of limb events including amputation. The association between calcification in lower extremity arteries and the severity of ischemia, however, has not been assessed. We thus sought to determine whether the extent of peripheral artery calcification was correlated with Rutherford chronic ischemia categories and hypothesized that it could independently contribute to worsening limb status.

Methods:

We retrospectively reviewed all patients presenting with symptomatic PAD who underwent evaluation by contrast and non-contrast CT scan of the lower extremities as part of their assessment. Demographic and cardiovascular risk factors were recorded. Rutherford ischemia categories were determined based on history, physical exam, and non-invasive testing. Peripheral artery calcification scores and the extent of occlusive disease were measured on non-contrast and contrast CT scans respectively. Spearman’s correlation testing was used to assess the relationship between occlusive disease and calcification scores. Multivariable logistic regression was utilized to identify factors associated with increasing Rutherford ischemia categories.

Results:

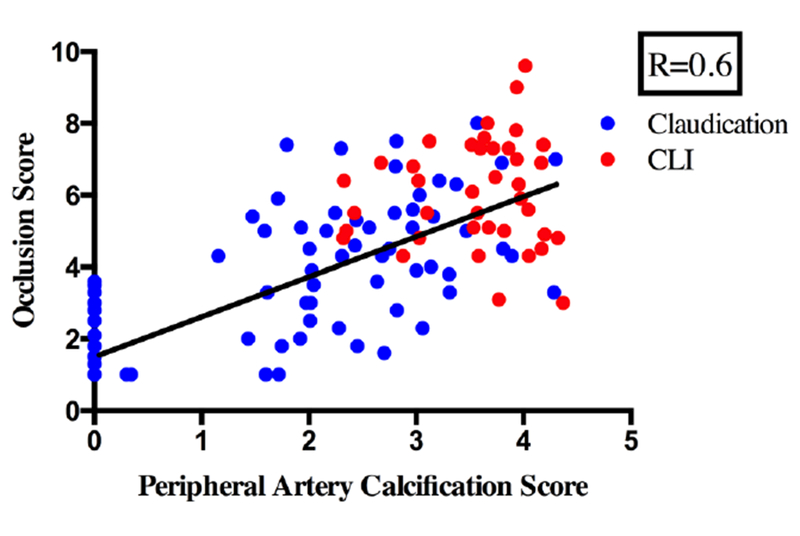

116 patients were identified including 75 with claudication and 41 with critical limb ischemia. In univariate regression, there was a significant association between increasing Rutherford ischemia category and age, diabetes duration, hypertension, the occlusion score, and peripheral artery calcification. There was a moderate correlation between the extent of occlusive disease and peripheral artery calcification scores (Spearman’s R=0.6). In multivariable analysis, only tobacco use (OR: 3.1, 95% CI:1.2-8.3), diabetes duration (OR: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01-1.08) , and the calcification score (OR:2.1 95% CI: 1.4-3.2) maintained an association with increasing ischemia categories after adjusting for relevant cardiovascular risk factors and the extent of occlusive disease.

Conclusions:

Peripheral artery calcification is independently associated with increased ischemia categories in patients with PAD. Further research aimed at understanding the relationship between arterial calcification and worsening limb ischemia is warranted.

Introduction

Lower extremity arterial calcification is associated with advancing age, diabetes duration, and the presence of renal disease.1 It is seen commonly in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) and is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.2, 3 It predicts amputation better than cardiovascular risk factors and the ankle brachial index (ABI) combined, and has been associated with worse outcomes after endovascular interventions.4-7 Quantification of peripheral artery calcification has become readily available through semi-automated protocols using non-contrast CT scans.5, 8

In the lower extremities, calcification is most prominently located in the media, and this pattern is distinct from that found in the coronary arteries.9 The contribution of lower extremity calcification to chronic ischemic symptoms, where plaque rupture is less likely to play a role, may thus be different than in the heart. The extent of functional impairment in patients with PAD is weakly correlated with anatomical measures of plaque burden, and it has been shown that response to therapy is variable.10, 11 Medial calcification has been related to increased arterial stiffness that can affect pedal perfusion.12 It is therefore possible that the extent of calcification in lower extremity arteries influences the severity of symptoms in patients with PAD, The relationship between arterial calcification and PAD symptoms, however, has not been explored. We thus sought to determine whether calcification in lower extremity arteries was correlated with severity of ischemia as defined by Rutherford’s categories, and further, whether this association could be used to explain some of the variability in presentation of PAD patients. Such a finding, if confirmed, could support further efforts to develop clinical therapies aimed at reducing calcification and improving outcomes in our patients with lower extremity arterial disease.

Methods

We retrospectively identified patients who underwent CT scan imaging of the lower extremities for assessment of peripheral artery disease (PAD) between January 2005 and November 2010 as part of an IRB-approved registry to assess lower extremity arterial calcification. We did not include patients presenting with symptoms of acute limb ischemia or those with a prior amputation above the ankle. Patients with evidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) as evidenced by a creatinine > 1.7 or EGFR < 30 were not included due to the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy during CTA. Individual risk factors were obtained from clinic notes and confirmed by review of the medical record and included tobacco use, diabetes duration, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Data from arterial Doppler studies including ankle brachial indices (ABIs) and waveforms were used to confirm the diagnosis of PAD. Only patients with non-invasive arterial studies within 1 month of CT imaging were included in this study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and conducted at Vanderbilt University Medical Center by the Primary Investigator and staff. The medical record was then reviewed for presenting vascular symptoms and patients were divided into Rutherford chronic limb ischemia categories 1 – 6 based on symptoms, foot exam, and non-invasive Doppler testing.13 Briefly, categories 1, 2, and 3 are used to specify patients with long-, medium-, and short-distance claudication. Category 4 denotes patients with ischemic rest pain, category 5 those with limited tissue loss, and category 6 those with large ischemic ulcers, significant tissue loss, necrosis, or gangrene.

Peripheral artery calcification was measured on non-contrast CT scans of the lower extremities. Briefly, cross sectional images of the legs were reviewed and areas of calcification greater than 1-mm2 and with a density of greater than 130 Hounsfield units were identified automatically by standardized scoring software. Calcified arterial segments were then manually selected with care to exclude bone from the mid-thigh superficial femoral artery to the widest portion of the ankle malleoli. Regions of interest along the superficial femoral, popliteal, anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal arteries were manually selected and labeled as we have previously reported.5 Individual calcium values for each artery in the lower extremity were added together to derive a single calcium score for each patient. Because the values of peripheral artery calcification (PAC) scores were skewed, log-transformed (PAC + 1) values were used for all statistical analyses. Investigators who were blinded to patient’s clinical status performed all calcium scoring after a brief training session. Inter-observer variability was evaluated previously and a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.98 (P<0.001) was found.14

We next quantified the extent of occlusive disease in lower extremity arteries on CT angiograms. This was completed using standardized protocols and a contrast volume of 110 – 130 mL. To do this, we applied the scoring system initially proposed by the Ad Hoc committee of the SVS/ISCVS.15 The system has been validated as a correlate of runoff resistance and predictor of bypass graft patency, limb salvage, and survival in patients undergoing lower extremity revascularization.15-20 The extent of disease in a specific territory (thigh or calf) was assessed by two study investigators blinded to the clinical categories using a scale of 1 to 10 where a score of 1 denotes patent vessels in that territory and a score of 10 denotes completely occluded vessels.

Statistical Analysis

Values for peripheral artery calcification were significantly skewed and transformed log10(PAC +1) were used for all analyses. Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rho) were calculated to evaluate the correlation between arterial calcification and the occlusion score. Univariate and multivariable ordinal logistic regression was performed to assess unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p-values for increasing chronic ischemia categories related to demographic and cardiovascular risk factors as well as calcification and occlusion scores. Statistically significant results were concluded if the 2-sided p-values were less than 0.05. Analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM version 22.0) and GraphPad Prism 5

Results

A total of 116 symptomatic patients who underwent CT scanning and arterial Doppler evaluation for initial assessment of PAD were identified. The mean age of all symptomatic patients was 62 years and 66% were men. (Table 1) On review of cardiovascular risk factors, 83% had a history of tobacco use, 65% had diabetes, 78% had hypertension, and 72% hyperlipidemia. The average number of cardiovascular risk factors per patient was 2.9. Of all patients, 65% had claudication and 35% had chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLI). The mean occlusion score was 4.5 out of a worst-case possible score of 10, and the median peripheral artery calcification score was 2.4.

Table 1:

Patient Demographics

| All Symptomatic N = 116 (%) | Claudication (Rutherford 1-3) N=75 | CLI (Rutherford 5-6) N=41 | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age years – mean (SD) | 62 (11) | 60 (11) | 66 (11) | 0.004 |

| Male Gender | 76 (66%) | 48 (64%) | 28 (68%) | 0.64 |

| White Race | 90 (78%) | 59 (79%) | 31 (76%) | 0.71 |

| Smoking | 96 (83%) | 61 (81%) | 35 (85%) | 0.58 |

| Diabetes | 75 (65%) | 41 (55%) | 34 (83%) | 0.002 |

| Duration years – median (IQR) | 4 (0-12) | 1 (0-8) | 10 (3-17) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 90 (78%) | 53 (71%) | 37 (90%) | 0.02 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 84 (72%) | 56 (75%) | 28 (68%) | 0.46 |

| Occlusion score – mean (SD) | 4.5 (2.1) | 4 (1-5) | 6 (5-7) | <.001 |

| PAC - mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.0 (0-2.8) | 3.7 (3.0-4.0) | <.001 |

SD: Standard Deviation, IQR: Interquartile Range, PAC: Peripheral Artery Calcification Score

We next investigated the association between the amount of calcification and extent of atherosclerotic occlusive disease in our patient population. The Spearman coefficient between the peripheral artery calcification and occlusive scores was 0.6 suggesting only a moderate correlation. (Figure 1) Ten patients had minimal occlusive disease by CT angiography suggesting that their symptoms were related to aorto-iliac occlusive disease. All patients presenting with limb-threatening ischemia had both increased occlusion and calcification scores. Interestingly, seven patients with limb-threatening ischemia had relatively mild occlusive disease (occlusion score less than 5) but all had high PAC scores suggesting that calcification or other undocumented factors play a role in ischemia.

Figure 1 :

Correlation of occlusion scores on the Y-axis versus PAC scores on the X-axis for individual patients

We next performed ordinal regression to identify associations between cardiovascular risk factors and increasing ischemia categories. (Table 2) Age, but not gender or white race was associated with increased Rutherford categories (P=0.02). In addition, diabetes and hypertension were strongly associated with increasing ischemia categories but tobacco use was only marginally associated (P=0.06), and history of hyperlipidemia was not associated. This may suggest that tobacco users mostly presented with milder categories of PAD whereas patients with diabetes were more likely to present with advanced stages of disease. Both the CT-determined occlusion (P<.001) and calcification scores (P<.001) were strongly associated with worse stages of ischemia =.

Table 2.

Univariate Odds Ratios and Confidence Interval for Increasing Rutherford Category

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | P-value |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age – per year | 1.03 (1.01-1.1) | 0.02 |

| Male Gender | 1.1 (0.5-2.1) | 0.89 |

| White Race | 1.2 (0.3-1.3) | 0.21 |

| Smoking | 2.3 (0.7-5.6) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes Duration – per year | 1.1 (1.03-1.1) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 3.5 (1.5-7.8) | 0.002 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.7 (0.4-1.5) | 0.42 |

| Occlusion score | 1.5 (1.3-1.8) | <.001 |

| PAC* | 2.4 (1.8-3.1) | <.001 |

PAC: Log10 (Agatston calcium score +1)

PAC: Peripheral Artery Calcification Score

We next used multivariable ordinal regression to identify independent predictors of increased ischemia category. (Table 3) In this analysis, age, hypertension, and the occlusion score no longer predicted increased Rutherford categories. However, a history of tobacco use (OR: 3.1, 95% CI: 1.1-7.9), diabetes duration (OR: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01-1.08), and the peripheral artery calcification score (OR: 1.9, 95% CI: 1.4-3.2) maintained their associations.

Table 3.

Multivariable Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Intervals for Increasing Rutherford Category

| Patient Characteristics | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.99 (0.9-1.02) | 0.46 |

| Smoking | 3.0 (1.1-7.9) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes Duration | 1.04 (1.01-1.08) | 0.04 |

| Hypertension | 1.8 (0.7-4.3) | 0.20 |

| Occlusion score | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | 0.28 |

| PAC* | 1.9 (1.3-2.8) | 0.001 |

PAC: Log10 (Agatston calcium score +1), PAC: Peripheral Artery Calcification Score

Discussion

In a cohort of patients undergoing CT scan imaging for PAD, we observed an association between the peripheral artery calcification score and Rutherford chronic ischemia category. In our final statistical model, the association was maintained after including cardiovascular risk factors and a quantified occlusion score. Importantly, occlusive index and calcification were only moderately correlated. To our knowledge, this is the first study to include both the calcification score and a measure of atherosclerotic occlusion in a model for prediction of ischemia categories.

Arterial calcification is thought to develop in the media through metabolic processes related to diabetes and renal disease, or in atherosclerotic plaques through mechanisms most commonly associated with inflammation. 21 Genetic factors including defects in genes for ENPP1, ABCC6, and NT5E are known to contribute to hereditary forms.22-24 Promoters of osteogenesis including members of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-msx2-wnt pathway and signaling through Pi have been implicated in smooth muscle cell transformation and calcification. Natural inhibitory mechanisms including Matrix Gla protein (MGP) expression and pyrophosphate are known to play an important role. Cellular and molecular pathways involving apoptosis, micro vesicles, and osteoclastic regulatory factors have been demonstrated in the pathologic progression of both the intimal and medial forms.25-31

The relation between arterial calcification and worse cardiovascular outcomes has previously been noted.32, 33 In an early study on the Pima Indian population of the Gila River Indian community in Arizona, Everhart et al found a strong association between medial calcification in foot arteries and increased rates of any amputation (adjusted OR 5.5, CI 2.1-14.4). The authors hypothesized that a positive association between medial calcification and arterial occlusion might provide a physiologic explanation for this relationship.32 Medial artery calcification was also a strong predictor of cardiovascular events including amputation in 1059 Finnish patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes.2 More recently, Huang with others showed in a group of 82 patients that those with leg calcium scores in the top quartile had increased amputation risk compared with the lowest quartile (adjusted OR 2.88 CI 1.18-12.72 P =0.003).3 In these studies, however, no attempt was made to quantify the extent of extremity atherosclerotic disease.

Indeed, tibial artery occlusive disease is more common in diabetic and renal failure patients with visible forefoot calcifications on plain x-rays.34, 35 In the coronaries, where calcium scoring has long been used to predict occlusive disease, Rumberger et al found a correlation coefficient between calcium and occlusive lesions of 0.9 when examined on pathologic samples36 In clinical studies involving the coronaries, the correlation between angiographic occlusion and calcium score was also found to be significant; however to a lesser degree in symptomatic patients (symptomatic R=0.51, asymptomatic R=0.85).37 In the lower extremities, this association has not been reported previously. Similar to these data in the coronaries, we found a moderate correlation in our symptomatic patient population (R=0.6). Interestingly, there was weak correlation when we included only those patients with limb-threatening ischemia (R=0.3). Notably, all patients with limb threatening ischemia had both significant calcification and atherosclerosis. Based on these data, it is possible that the combination of vessel calcification and occlusion has a more significant effect on pedal perfusion than either factor alone. An unexpected finding in our multivariable analysis was that the occlusion score lost its ability to predict increased Rutherford category. Other investigators have also shown a weak correlation between plaque volume and limb function in PAD patients.10 This suggests that other demographic and cardiovascular risk factors that lead to occlusive disease may be more predictive, or that the extent of calcification may influence the level of ischemia. It may also explain why some patients with diabetes and renal disease may present with evidence of severe ischemia but only mild-to-moderate occlusive disease.

One potential explanation for the effect of arterial calcification on increased chronic ischemia categories is through its effects on arterial stiffness. Calcification in the femoral artery, assessed using CT, was associated with reduced arterial compliance in patients on dialysis.38 More recently, in Framingham Heart Study Third Generation and Offspring Cohort participants free of cardiovascular disease, Tsao et al found a strong correlation between carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity and calcification measures in the aorta, with odds ratios per standard deviation of 2.69 [95% CI 2.17-3.35] for thoracic aortic, and 1.47 [95% CI 1.26-1.73] for abdominal aortic calcification.39 In patients with type 2 diabetes, those with higher brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity had decreased arterial inflow to the calf and foot by MRI and decreased flow volume in the popliteal artery.40, 41 Patients with type 2 diabetes and symptomatic PAD had significantly higher femoral artery stiffness parameters than those without PAD.42 And, in an interventional study on patients with claudication, Ahmiastos with others found that increased walking distance in patients treated with the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor ramipril was correlated with changes in indices of arterial stiffness.43 It may thus be hypothesized that calcification, by contributing to arterial stiffness, may worsen ischemia in regions distal to occlusive lesions. This may also provide an explanation for the significant variability seen in presentation for patients with similar amounts of occlusive disease.

Another potential explanation for these effects is through collateral formation. In the coronaries, poor collateral development has been associated with diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and advanced age.44, 45 Similarly, in patients with chronic kidney disease, diabetes and hypertension were found to be significant predictors of poor collateral formation.46 Studies have shown that decreased collateral formation in the coronaries is predictive of infarction size and mortality.47, 48 The relationship between calcification and collateral development in lower extremities, however, has not been addressed.

The present study has limitations in that it was retrospectively conducted at a single academic medical center and is cross-sectional in nature. The decision to obtain CT scan imaging as the initial evaluation, rather than proceed directly to digital subtraction angiography, was made by the attending vascular surgeon. Patients with decreased renal function were generally investigated with DSA because of the ability to use lower contrast doses and thus are not represented in this study. As such, the data may not be generalizable to the wider population of patients with peripheral artery disease and we are unable to infer causality or mechanistic effects. Although our efforts have focused on peripheral artery calcification, it is possible that more a global assessment of calcification may produce different results. Calcification in the thoracic and abdominal aorta, iliac, and carotid vessels, however, is generally well correlated.49, 50 Our assessment of occlusive disease was performed on contrast-enhanced CT scans of the legs and it was limited to femoral, popliteal, and tibial vessels. As such, more proximal (ileo-femoral) or distal (pedal) occlusive lesions could have been missed and this may have affected our results. Such disease, however, is unlikely to occur in an isolated form, and our measurements included the adductor canal region of the fem-pop segment, which is most commonly affected by atherosclerotic occlusive disease.51 More advanced methods of quantifying plaque volume, and calcified versus non-calcified plaque percentages using higher resolution CT scans52, IVUS53, or MRI54 may yield different results or provide greater insight into this relationship in the future. Increased precision in methods for assessing lower extremity calcification have recently been reported using high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography but this would not likely alter the overall results.55 Our study population included patients with bilateral symptoms and thus we assessed occlusion and calcification scores in both lower extremities. Future efforts will seek to refine our methods to address only the most symptomatic extremity. It is possible that some tibial occlusive lesions were missed in patients with extensive calcification. However, our protocol for measuring occlusive disease involved comparison of contrast and non-contrast images in cross-sectional and reconstructed longitudinal views to confirm that calcified arteries were not being scored as patent. An ideal study would have included asymptomatic, age-matched control patients. It was felt, however, that the risk of contrast angiography was not justified in this population and so occlusion scores were not available. The study focuses on standard demographic and cardiovascular risk factors, however, it is possible that other unknown elements that contribute to symptom severity in patients with PAD remain and were not included in our model.

Conclusions:

Peripheral artery calcification is associated with worsening limb ischemia categories in patients with PAD. The association is maintained after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors and a measure of atherosclerotic occlusive disease. Further research aimed at understanding the role of arterial calcification in limb ischemia is warranted.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge the following individuals who contributed to this project. Holly Beavers, RN, David Brinkley, M.D. Paul Schumacher, M.D., Dale Deas, B.S.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by grants NIH DK067368 to Raul Guzman, and NIH T32 Harvard-Longwood Research Training in Vascular Surgery grant HL007734 to Sara Zettervall. It was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR001102) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Portions of this study were presented in an interactive poster session during the VRIC/ATVB meeting in San Francisco, CA May, 7-9 2015.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rocha-Singh KJ, Zeller T, Jaff MR. Peripheral arterial calcification: prevalence, mechanism, detection, and clinical implications. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2014;83(6):E212–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Risk factors predicting lower extremity amputations in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1996;19(6):607–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang CL, Wu IH, Wu YW, Hwang JJ, Wang SS, Chen WJ, et al. Association of lower extremity arterial calcification with amputation and mortality in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease. PLoS One 2014;9(2):e90201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David Smith C, Gavin Bilmen J, Iqbal S, Robey S, Pereira M. Medial artery calcification as an indicator of diabetic peripheral vascular disease. Foot Ankle Int 2008;29(2):185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzman RJ, Brinkley DM, Schumacher PM, Donahue RMJ, Beavers H, Qin X. Tibial artery calcification as a marker of amputation risk in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51(20):1967–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aragon-Sanchez J, Lazaro-Martinez JL. Factors associated with calcification in the pedal arteries in patients with diabetes and neuropathy admitted for foot disease and its clinical significance. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2013;12(4):252–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang IS, Lee W, Choi BW, Choi D, Hong MK, Jang Y, et al. Semiquantitative assessment of tibial artery calcification by computed tomography angiography and its ability to predict infrapopliteal angioplasty outcomes. J Vasc Surg 2016;64(5):1335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohtake T, Oka M, Ikee R, Mochida Y, Ishioka K, Moriya H, et al. Impact of lower limbs’ arterial calcification on the prevalence and severity of PAD in patients on hemodialysis. J Vasc Surg 2011;53(3):676–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Neill WC, Han KH, Schneider TM, Hennigar RA. Prevalence of nonatheromatous lesions in peripheral arterial disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015;35(2):439–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson JD, Epstein FH, Meyer CH, Hagspiel KD, Wang H, Berr SS, et al. Multifactorial determinants of functional capacity in peripheral arterial disease: uncoupling of calf muscle perfusion and metabolism. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54(7):628–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simons JP, Goodney PP, Nolan BW, Cronenwett JL, Messina LM, Schanzer A. Failure to achieve clinical improvement despite graft patency in patients undergoing infrainguinal lower extremity bypass for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg 2010;51(6):1419–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atkinson J Age-related medial elastocalcinosis in arteries: mechanisms, animal models, and physiological consequences. J Appl Physiol 2008;105(5):1643–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutherford RB, Baker JD, Ernst C, Johnston KW, Porter JM, Ahn S, et al. Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: revised version. J Vasc Surg 1997;26(3):517–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guzman RJ, Brinkley DM, Schumacher PM, Donahue RM, Beavers H, Qin X. Tibial artery calcification as a marker of amputation risk in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51(20):1967–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutherford RB, Flanigan DP, Gupta SK, Johnston KW, Karmody A, Whittemore AD, et al. Suggested standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia. J Vasc Surg 1986;4(1):80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterkin GA, Manabe S, LaMorte WW, Menzoian JO. Evaluation of a proposed standard reporting system for preoperative angiograms in infrainguinal bypass procedures: angiographic correlates of measured runoff resistance. J Vasc Surg 1988;7(3):379–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okadome K, Onohara T, Yamamura S, Mii S, Sugimachi K. Evaluation of proposed standards for runoff in femoropopliteal arterial reconstructions: correlation between runoff score and flow waveform pattern. A preliminary report. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1991;32(3):353–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alback A, Biancari F, Saarinen O, Lepantalo M. Prediction of the immediate outcome of femoropopliteal saphenous vein bypass by angiographic runoff score. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1998;15(3):220–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson-Fawcett M, Moon M, Hands L, Collin J. The significance of donor leg distal runoff in femorofemoral bypass grafting. Aust N Z J Surg 1998;68(7):493–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biancari F, Alback A, Ihlberg L, Kantonen I, Luther M, Lepantalo M. Angiographic runoff score as a predictor of outcome following femorocrural bypass surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1999;17(6):480–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demer LL, Tintut Y. Inflammatory, metabolic, and genetic mechanisms of vascular calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34(4):715–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rutsch F, Ruf N, Vaingankar S, Toliat MR, Suk A, Hohne W, et al. Mutations in ENPP1 are associated with ‘idiopathic’ infantile arterial calcification. Nat Genet 2003;34(4):379–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nitschke Y, Baujat G, Botschen U, Wittkampf T, du Moulin M, Stella J, et al. Generalized arterial calcification of infancy and pseudoxanthoma elasticum can be caused by mutations in either ENPP1 or ABCC6. Am J Hum Genet 2012;90(1):25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.St Hilaire C, Ziegler SG, Markello TC, Brusco A, Groden C, Gill F, et al. NT5E mutations and arterial calcifications. N Engl J Med 2011;364(5):432–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byon CH, Sun Y, Chen J, Yuan K, Mao X, Heath JM, et al. Runx2-upregulated receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand in calcifying smooth muscle cells promotes migration and osteoclastic differentiation of macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011;31(6):1387–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.New SE, Goettsch C, Aikawa M, Marchini JF, Shibasaki M, Yabusaki K, et al. Macrophage-derived matrix vesicles: an alternative novel mechanism for microcalcification in atherosclerotic plaques. Circ Res 2013;113(1):72–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shanahan CM. Autophagy and matrix vesicles: new partners in vascular calcification. Kidney Int 2013;83(6):984–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shao J-s Aly Za Lai C-F Cheng S-l, Cai J, Huang E, et al. Vascular Bmp msx2 wnt signaling and oxidative stress in arterial calcification. Ann NY Acad Sci 2007;1117(1):40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crouthamel MH, Lau WL, Leaf EM, Chavkin NW, Wallingford MC, Peterson DF, et al. Sodium-dependent phosphate cotransporters and phosphate-induced calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells: redundant roles for PiT-1 and PiT-2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013;33(11):2625–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liabeuf S, Bourron O, Vemeer C, Theuwissen E, Magdeleyns E, Aubert CE, et al. Vascular calcification in patients with type 2 diabetes: the involvement of matrix Gla protein. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2014;13:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lomashvili KA, Narisawa S, Millan JL, O’Neill WC. Vascular calcification is dependent on plasma levels of pyrophosphate. Kidney Int 2014;85(6):1351–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Everhart JE, Pettitt DJ, Knowler WC, Rose FA, Bennett PH. Medial arterial calcification and its association with mortality and complications of diabetes. Diabetologia 1988;31(1):16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niskanen L, Siitonen O, Suhonen M, Uusitupa MI. Medial artery calcification predicts cardiovascular mortality in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1994;17(11):1252–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chantelau E, Lee KM, Jungblut R. Association of below-knee atherosclerosis to medial arterial calcification in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1995;29(3):169–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.An WS, Son YK, Kim SE, Kim KH, Yoon SK, Bae HR, et al. Vascular calcification score on plain radiographs of the feet as a predictor of peripheral arterial disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol 2010;42(3):773–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, Sheedy PF, Schwartz RS. Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area. A histopathologic correlative study. Circulation 1995;92(8):2157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guerci AD, Spadaro LA, Popma JJ, Goodman KJ, Brundage BH, Budoff M, et al. Relation of coronary calcium score by electron beam computed tomography to arteriographic findings in asymptomatic and symptomatic adults. Am J Cardiol 1997;79(2):128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sigrist MK, McIntyre CW. Vascular calcification is associated with impaired microcirculatory function in chronic haemodialysis patients. Nephron Clin Pract 2008;108(2):c121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsao CW, Pencina KM, Massaro JM, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vasan RS, et al. Cross-sectional relations of arterial stiffness, pressure pulsatility, wave reflection, and arterial calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014;34(11):2495–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki E, Kashiwagi A, Nishio Y, Egawa K, Shimizu S, Maegawa H, et al. Increased arterial wall stiffness limits flow volume in the lower extremities in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2001;24(12):2107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshimura T, Suzuki E, Ito I, Sakaguchi M, Uzu T, Nishio Y, et al. Impaired peripheral circulation in lower-leg arteries caused by higher arterial stiffness and greater vascular resistance associates with nephropathy in type 2 diabetic patients with normal ankle-brachial indices. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008;80(3):416–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taniwaki H, Shoji T, Emoto M, Kawagishi T, Ishimura E, Inaba M, et al. Femoral artery wall thickness and stiffness in evaluation of peripheral vascular disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis 2001;158(1):207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahimastos AA, Dart AM, Lawler A, Blombery PA, Kingwell BA. Reduced arterial stiffness may contribute to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor induced improvements in walking time in peripheral arterial disease patients. J Hypertens 2008;26(5):1037–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsu PC, Juo SH, Su HM, Tsai WC, Voon WC, Lai WT, et al. Predictor of poor coronary collaterals in elderly population with significant coronary artery disease. Am J Med Sci 2013;346(4):269–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yilmaz MB, Caldir V, Guray Y, Guray U, Altay H, Demirkan B, et al. Relation of coronary collateral vessel development in patients with a totally occluded right coronary artery to the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2006;97(5):636–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hsu PC, Juo SH, Su HM, Chen SC, Tsai WC, Lai WT, et al. Predictor of poor coronary collaterals in chronic kidney disease population with significant coronary artery disease. BMC Nephrol 2012;13:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Charney R, Cohen M. The role of the coronary collateral circulation in limiting myocardial ischemia and infarct size. Am Heart J 1993;126(4):937–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meier P, Hemingway H, Lansky AJ, Knapp G, Pitt B, Seiler C. The impact of the coronary collateral circulation on mortality: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2012;33(5):614–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allison MA, Hsi S, Wassel CL, Morgan C, Ix JH, Wright CM, et al. Calcified atherosclerosis in different vascular beds and the risk of mortality. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012;32(1):140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bastos Goncalves F, Voute MT, Hoeks SE, Chonchol MB, Boersma EE, Stolker RJ, et al. Calcification of the abdominal aorta as an independent predictor of cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Heart 2012;98(13):988–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walsh DB, Powell RJ, Stukel TA, Henderson EL, Cronenwett JL. Superficial femoral artery stenoses: characteristics of progressing lesions. J Vasc Surg 1997;25(3):512–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakazato R, Shalev A, Doh J-H, Koo B-K, Gransar H, Gomez MJ, et al. Aggregate Plaque Volume by Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography Is Superior and Incremental to Luminal Narrowing for Diagnosis of Ischemic Lesions of Intermediate Stenosis Severity. J Am Coll Cardio 2013;62(5):460–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medina R, Wahle A, Olszewski ME, Sonka M. Three methods for accurate quantification of plaque volume in coronary arteries. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2003;19(4):301–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Isbell DC, Meyer CH, Rogers WJ, Epstein FH, DiMaria JM, Harthun NL, et al. Reproducibility and reliability of atherosclerotic plaque volume measurements in peripheral arterial disease with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2007;9(1):71–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patsch JM, Zulliger MA, Vilayphou N, Samelson EJ, Cejka D, Diarra D, et al. Quantification of lower leg arterial calcifications by high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography. Bone 2014;58:42–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]