Abstract

Introduction:

A prospective cohort study was undertaken from November 2010 to March 2012 at Kalawati Saran Children's Hospital (KSCH), Lady Hardinge Medical College (LHMC), New Delhi. The study included all HIV positive children aged between 0-15 years that were registered in the anti-retroviral therapy (ART) centre during the study period. HIV +ve children enrolled at the ART centre were started on ART on the basis of CD4counts (National/NACO guidelines).

Materials and Methods:

Various samples were collected from the patients depending on their presenting complaints as per the standard protocols. These included stool, sputum, gastric aspirate, urine, blood, pus and CSF. All the samples were processed in the microbiology laboratory as per the standard techniques. Majority of children presented to the hospital with respiratory system involvement. Fever with cough was the presenting symptom in around half of all the children suggesting involvement of upper and/or lower respiratory tract. Diarrhea and protein energy malnutrition (PEM) were the next most common findings. Clinical presentations more suggestive of HIV (e.g. generalized lymphadenopathy, mucocutaneous lesions, oral thrush etc.) were less commonly the presenting complaints.

Results:

OIs are still a major health hazard in children living with HIV/AIDS. The pattern of OIs encountered in a developing country like ours is different from the pattern observed in western countries. Tuberculosis is still a major problem as well as other bacterial infections. Fungal and parasitic infections are also a common health hazard. ART is a major pillar for combat against this dreadful disease. As suggested by our study, timely initiation of ART leads to an increase in CD4+ counts which is imperative in protection against OIs in HIV infected patients. Hence, routine monitoring of CD4+ counts and timely initiation and continuation of ART should be a major event in the life of a child infected with HIV.

Key words: Children living with HIV/AIDS, highly active antiretroviral therapy, opportunistic infectionsChildren living with HIV/AIDS, highly active antiretroviral therapy, opportunistic infections

INTRODUCTION

AIDS was first recognized in the United States in the summer of 1981, when the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the unexplained occurrence of Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly P. carinii) pneumonia in five previously healthy homosexual men in Los Angeles and of Kaposi's sarcoma with or without P. jiroveci pneumonia in 26 previously healthy homosexual men in New York and Los Angeles.[1]

The spectrum of opportunistic infections (OIs), with which most of the patients present in the clinics, reflects a wide variety of other endemic diseases prevalent within each region. In contrast to western countries, a small number of opportunistic pathogens cause the majority of infections in India. In India, very commonly the diagnosis of OIs is made clinically based on signs and symptoms or only when the disease is already quite advanced. However, the crux is that most of the opportunistic pathogens causing infection can be easily identified in the laboratory. Most of these infections are preventable and effective treatment is available to treat them. As most of the HIV/AIDS patients with OIs, especially children, do not present with typical signs and symptoms, laboratory diagnosis becomes even more important.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective cohort study was conducted from November 2010 to March 2012 at Kalawati Saran Children's Hospital (KSCH), Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. The study included all HIV-positive children aged between 0 and 15 years who were registered in the antiretroviral therapy (ART) center during the study. KSCH is a 372-bedded children tertiary care hospital with a dedicated pediatric ART center. The ART center has more than 100 children living with HIV/AIDS (CLHA) enrolled for treatment and monitoring. HIV-positive children enrolled at the ART center were started on ART on the basis of CD4 counts (National/NACO guidelines). The children were enrolled in the study only after obtaining written, informed consent from the parents of children. Confidentiality was maintained strictly during and after the study.

Screening for opportunistic infections

Various samples were collected from the patients depending on their presenting complaints as per the standard protocols.[1] These included stool, sputum, gastric aspirate, urine, blood, pus, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Samples requiring invasive procedure (blood, CSF, etc.) were collected only when indicated. All the samples were processed in the microbiology laboratory as per the standard techniques. Stool samples were first concentrated using formol-ether sedimentation technique (modified Ritchief's method) and Sheather's sugar flotation technique and were screened for parasitic infections by microscopy. Modified Ziehl–Neelsen (ZN) stain was also made to screen for oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum. Stool specimens were cultured for identifying any bacterial pathogen.[1] Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for Cryptosporidium antigen in stool was performed using the commercially available kit, Cryptosporidium antigen (stool) ELISA (DRG International, Inc., USA). Sputum and gastric aspirate samples received in the lab were screened using Gram stain, modified ZN staining (for acid-fast bacilli), 10% KOH wet mounts (for fungal pathogens), and modified toluidine blue-O and Giemsa staining from detecting cysts/trophozoites of P. jiroveci.[2] Urine samples received in the laboratory were processed using the standard method and identification of the bacterial colonies (if any) was done based on colony morphology and using the appropriate biochemical tests.[1,2] Blood samples received in blood cultures were incubated at 37°C for 18–24 h and then serially subcultured after 24 h, 72 h, and 7 days. CSF was subjected to microscopic examination and cultured using the standard techniques.[1]

RESULTS

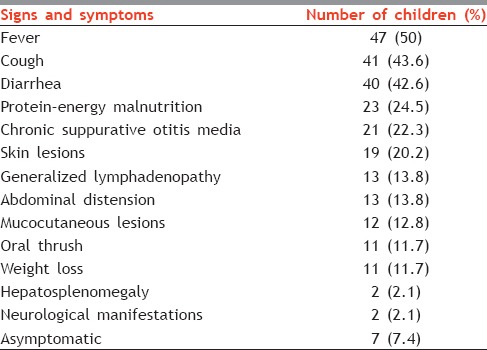

In our study, the majority of children presented to the hospital with respiratory system involvement. Fever with cough was the presenting symptom in around half of all the children suggesting the involvement of upper and/or lower respiratory tract. Diarrhea and protein–energy malnutrition were the next most common findings being the presenting symptoms in 42.6% and 24.5% children, respectively. Clinical presentations more suggestive of HIV (e.g., generalized lymphadenopathy, mucocutaneous lesions, oral thrush) were less commonly the presenting complaints [Table 1]. Children also came with the other presentations such as skin lesions (20.2%), weight loss (12.8%), and neurological manifestations (2.1%).

Table 1.

Various presenting symptoms of study subjects

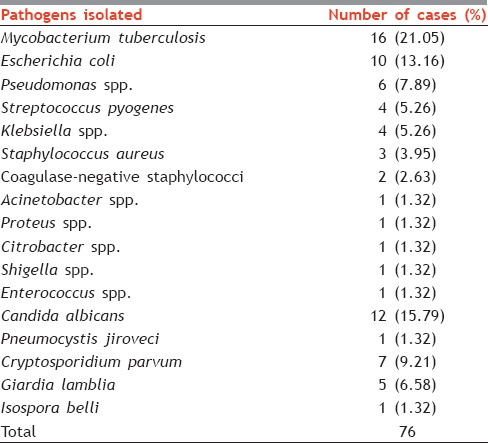

As many as 49 (52.13%) children developed an OI during the study. A total of 76 OIs were detected during the study from these 49 children. The most common infection type was bacterial (65.78%), with tuberculosis (TB) being most common (32%) [Table 2]. Infection with Candida albicans was the most common fungal infection (15.79%) encountered during the study. Infection with C. parvum (9.21%) and Giardia lamblia (6.58%) were the most common parasitic infections seen in the study group. A list of all the pathogens encountered is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of all the pathogens isolated during the study

In our study, of 94 subjects, 49 (52.13%) were not on ART at the time of enrollment in the study. Their mean CD4+ count at the time of enrollment was 621.22 cells/μl (range = 414 cells/μl to 2557 cells/μl). Of these 49 children, 33 were eventually put on ART during the course of study.

In the study group, 45 (47.87%) children were already on ART at the time of enrollment. At the initiation of ART in these children, the mean CD4+ count was 274.27 (range = 11 cells/μl to 373 cells/μl). After 6 months of ART, the mean CD4+ count increased to 515.6 cells/μl, and after 12 months, it further increased to 631.57 cells/μl.

In our study, 42 (55.26%) OIs occurred in children with CD4+ counts below 250 cells/μl, 52 (68.42%) OIs occurred in children with CD4+ counts <350 cells/μl, 64 (84.21%) OIs occurred in children with CD4+ counts <500 cells/μl, and 12 (15.79%) OIs occurred in children with CD4+ cell count above 500 cells/μl [Table 3].

Table 3.

Percentage of opportunistic infections seen in children with various ranges of CD4+cell counts per μl in our study (%)

DISCUSSION

The present study was done to assess the spectrum of OIs and their prevalence in children <15 years of age living with HIV/AIDS. Our study demonstrated that the spectrum of OIs in HIV-positive children is very wide. As many as 76 bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections were detected in 94 children using conventional techniques.

From this study, we can conclude that conventional signs and symptoms which are more indicative of HIV infection may not be the presenting complaints in children suffering from HIV. They may, in fact, present with more generalized symptoms. In this, fever (50%) and cough (43.6%) were the most common presenting symptoms in HIV-positive children, followed by diarrhea (42.6%). Similar findings have been reported by other authors from India. Gomber et al. found fever (83%), cough (50.8%), and diarrhea (38.9%) to be the most common presenting symptoms in children.[3] In another study, Patel et al. reported fever, cough, weight loss, diarrhea, and oral thrush to be the most common symptoms in HIV-infected adult patients.[4]

OIs are still a major health hazard in CLHA. The pattern of OIs encountered in a developing country like ours is different from the pattern observed in western countries. Among the bacterial infections, TB is still a major health hazard in HIV-positive children and should be strongly considered as a diagnosis, especially if family history of TB is present. In our study, the most common bacterial infection encountered was Mycobacterium tuberculosis with 16 (32%) cases followed by Escherichia coli (20%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12%). These findings correlate well with other authors. Aggarwal et al., in their study at Amritsar, reported M. tuberculosis (32.75%) as the most common bacterial respiratory pathogen, followed by Klebsiella spp. (23.8%), P. aeruginosa (12.69%), and Staphylococcus aureus (12.69%).[5,6] The incidence rate of bacterial infections came out to be 69.54 cases per 1000 HIV-positive children in New Delhi.

Fungal infections form a significant proportion of OI in HIV-infected patients. The total incidence rate of fungal infection was calculated as 18.08 cases per 1000 HIV-positive patients in New Delhi. Oral thrush was the most common fungal infection.

The most common fungal isolate was C. albicans. Patel et al. reported C. albicans in 26.73% patients.[4] In a study from South India, Srirangaraj and Venkatesha reported infection by C. albicans in 27.2% cases.[7] Fungal infections make up a significant portion of OIs. Oral candidiasis, usually caused by C. albicans, occurs in 15–40% of HIV-infected children.[8]

In our study, P. jiroveci was isolated from one (1.32%) patient. In India, low rates (0.7–7%) of infection with P. jiroveci have been reported.[9,10,11,12] Srirangaraj and Venkatesha, in their study, found P. jiroveci infection in 1.1% cases.[7] In another study from Mumbai, Merchant et al. found the rate of isolation of P. jiroveci to be 3.88%.[13] Some reasons for this low incidence of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia infection rate could be the predominance of the other pulmonary diseases such as TB, and due to under-diagnosis of incident cases.[14]

Among parasitic infections, Cryptosporidium spp. was the most common (9.21%). Infection with Isospora spp. was detected in 1.32% children and G. lamblia infection was diagnosed in 5 (6.58%) children. Patel et al.[4] found Cryptosporidium spp. infection in 19.8% patients, Isospora belli infection in 2.97% cases, and G. lamblia in 1.98% cases. I. belli was found as the most common parasite by Gupta at Jamnagar (17.24%) and Kumar at Chennai (18%).[15,16] In another study from North India, Mohandas et al. found Cryptosporidium (10.8%) followed by G. lamblia (8.3%) as the most common parasitic OIs in Northern India.[17] The incidence rate of parasitic infections came out to be 18.08 cases per 1000 HIV-positive children in New Delhi.

Risk factors for the development of opportunistic infections

CD4 counts

In our study, we found that there is a very clear correlation of fall in CD4+ counts and occurrence of OIs. In our study, 68.42% OIs were seen below CD4+ count of 350 cells/μl and 84.21% OIs occurred below the CD4+ count of 500 cells/μl. Severe et al. and the Strategies for Management of ART (SMART) study group in their study also demonstrated the same.[18,19] However, in our study, we also found that 15.79% of OIs occurred in the window of CD4 counts of 350 and 500 cells/μl. Specific data are limited to guide recommendations for when to start highly active ART (HAART) in children with an acute OI. The decision of when to start HAART in a child with an acute or latent OI needs to be individualised and will vary by the degree of immunologic suppression in the child before he or she starts HAART.[20] Gallant and Kitahata et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of HAART among patients with CD4+ <500/μl in reducing mortality and clinical events including non-AIDS defining events.[21,22] Mauskopf et al.[23] used a Monte Carlo simulation model to track HIV disease progression and to indirectly estimate the outcomes and costs of treatment when initiated at various CD4 cell counts. Using this approach, initiation of HAART at a CD4 cell count more than 350 cells/μl was seen to result in a longer quality-adjusted survival compared to starting HAART at lower CD4 cell counts. Although treatment guidelines currently generally recommend that HIV-infected patients with a CD4 cell count <350 cells/μl should receive HAART, guidelines for those with higher CD4 cell counts are less clear-cut. Apart from analyses on a subset of patients in the SMART trial,[19] there are no data from randomised trials to inform the optimal time to start HAART in these patients and guidelines are largely based on evidence from observational studies. Initiating ART at CD4 cell count of 350 cells/μl might prevent around 16% of OIs seen in this windows period.

ART is a major pillar for combat against this dreadful disease. As suggested by our study and numerous others as well, timely initiation of ART leads to an increase in CD4+ counts which is imperative in protection against OIs in HIV-infected patients. Hence, routine monitoring of CD4+ counts and timely initiation and continuation of ART should be a major event in the life of a child infected with HIV.

The WHO stage of the disease

We found that 84% of bacterial infections, 92.31% of fungal infections, and 76.92% of parasitic infections occurred in children who were diagnosed to be in the WHO clinical stage III or IV at the time of presentation. Using Chi-square test, we assessed the association of the WHO clinical stage at presentation and occurrence of OIs. We found that there is a statistically significant association (P < 0.05) between the WHO clinical stage at the time of presentation and the occurrence of OIs. OIs tend to increase in occurrence as the WHO clinical stage increases.

Family history of tuberculosis

Of the 16 patients who were diagnosed as having TB in our study, 9 (56.25%) children had at least one parent as a known case of TB. Using Chi-square test, the association of family history of TB with TB infection in HIV-positive child came out to be statistically significant (P < 0.05).

HIV-positive children with TB almost always are infected by an adult in their daily environment, and their disease represents the progression of primary infection rather than the reactivation disease commonly observed among adults.[24] Identification and treatment of the source patient and evaluation of all exposed members of the household are particularly important because other secondary TB cases and latent infections with M. tuberculosis often are found.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collee JG, Miles RS, Watt B. Mackie and McCartney, Practical Medical Microbiology. 14th ed. New Delhi: Elsevier; 1996. Test for identification of bacteria; pp. 95–149. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collee JG, Miles RS, Watt B. Mackie and McCartney, Practical Medical Microbiology. 14th ed. New Delhi: Elsevier; 1996. Test for identification of bacteria; p. 736.p. 750. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomber S, Kaushik JS, Chandra J, Anand R. Profile of HIV infected children from Delhi and their response to antiretroviral treatment. Indian Pediatr. 2011;48:703–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel SD, Kinariwala DM, Javadekar TB. Clinico-microbiological study of opportunistic infection in HIV seropositive patients. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2011;32:90–3. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.85411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggarwal A, Arora U, Bajaj R, Kumari K. Clinicomicrobiological study in HIV seropositive patients. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2005;6:142–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shailaja VV, Pai LA, Mathur DR, Lakshmi V. Prevalence of bacterial and fungal agents causing lower respiratory tract infections in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2004;22:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srirangaraj S, Venkatesha D. Opportunistic infections in relation to antiretroviral status among AIDS patients from South India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29:395–400. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.90175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domachowske JB. Pediatric human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:448–68. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.4.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumarasamy N, Solomon S, Flanigan TP, Hemalatha R, Thyagarajan SP, Mayer KH. Natural history of human immunodeficiency virus disease in Southern India. 2003;36:79–85. doi: 10.1086/344756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gothi D, Joshi JM. Clinical and laboratory observations of tuberculosis at a Mumbai (India) clinic. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:97–100. doi: 10.1136/pmj.2003.008185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanjewar DN, Duggal R. Pulmonary pathology in patients with AIDS: An autopsy study from Mumbai. HIV Med. 2001;2:266–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2001.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rupali P, Abraham OC, Zachariah A, Subramanian S, Mathai D. Aetiology of prolonged fever in antiretroviral-naïve human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults. Natl Med J India. 2003;16:193–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merchant RH, Oswal JS, Bhagwat RV, Karkare J. Clinical profile of HIV infection. Indian Pediatr. 2001;38:239–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumarasamy N, Vallabhaneni S, Flanigan TP, Mayer KH, Solomon S. Clinical profile of HIV in India. Indian J Med Res. 2005;121:377–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta M, Sinha M, Raizada N. Opportunistic intestinal protozoan parasitic infection in HIV seropositive patient in Jamnagar, Gujarat. SAARC J Tuberc Lung Dis HIV AIDS. 2008;1:22–5. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar SS, Ananthan S, Lakshmi P. Intestinal parasitic infection in HIV infected patients with Diarrhoea in Chennai. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2002;20:88–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohandas, Sehgal R, Sud A, Malla N. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic pathogens in HIV-seropositive individuals in Northern India. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2002;55:83–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Severe P, Juste MA, Ambroise A, Eliacin L, Marchand C, Apollon S, et al. Early versus standard antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected adults in Haiti. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:257–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strategies for Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (SMART) Study Group. Emery S, Neuhaus JA, Phillips AN, Babiker A, Cohen CJ, et al. Major clinical outcomes in antiretroviral therapy (ART)-naive participants and in those not receiving ART at baseline in the SMART study. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1133–44. doi: 10.1086/586713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections among HIV – Exposed and HIV-Infected Children. [Last accessed on 2012 Apr 14]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr58e0826a1.htm .

- 21.Gallant JE. When to start antiretroviral therapy? NA-ACCORD stimulates the debate. AIDS Read. 2009;19:49–50. 61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, Merriman B, Saag MS, Justice AC, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1815–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mauskopf J, Kitahata M, Kauf T, Richter A, Tolson J. HIV antiretroviral treatment: Early versus later. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:562–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bakshi SS, Alvarez D, Hilfer CL, Sordillo EM, Grover R, Kairam R. Tuberculosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. A family infection. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:320–4. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160270082027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]