Abstract.

Antimicrobial overuse contributes to antimicrobial resistance. Empiric use of antimicrobials for diarrheal illness is warranted only in a minority of cases, because of its self-limiting nature and multifactorial etiology. This study aims to describe the factors contributing to antimicrobial overuse for diarrheal disease among children less than 5 years of age in rural Bangladesh. A total of 3,570 children less than 5 years of age presenting with diarrhea in a tertiary level hospital were enrolled in the study. The rate of antimicrobial use at home was 1,395 (39%), compared with 2,084 (89%) during a hospital visit. In a multivariate analysis, factors associated with antimicrobial use at home included residence located more than 5 miles from a hospital; use of zinc and oral rehydration salts at home; vomiting; greater than 10 stools per 24 hours; diarrheal duration greater than 3 days; and rotavirus diarrhea (P < 0.05 for all). Characteristics of children more likely to be given antimicrobials in a health-care setting included greater than 10 stools per 24 hours; duration of diarrhea greater than 3 days; use of antimicrobials before hospital presentation; fever (≥ 37.8°C); rectal straining; and Shigella infection (P < 0.05 for all). The most commonly used drugs in rotavirus diarrhea were azithromycin and erythromycin, both before hospital presentation and during hospital admission. Our study underscores the importance of diligent vigilance on the rationale use of antimicrobials both at home and in health-care facilities with a special concern for children less than 5 years of age living in rural Bangladesh.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, abuse of antimicrobials is found to have several negative consequences, including drug-related adverse events, the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria, the development of Clostridium difficile infection, negative impact on gut microbiota, and the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens leading to longer hospital stays, increased patient mortality, and increased health-care costs with under-treatment risks.1 The prevailing emergence of increasingly resistant bacterial strains to antimicrobial agents is an alarming public health threat.2,3 The relationship between antimicrobial abuse and resistance development is strong and has been supported by several studies.3–5

Diarrheal disease is a leading killer of children under five worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of antimicrobials only in shigellosis and cholera, and most other diarrhea-causing pathogens do not require antimicrobials.6,7 Rotavirus and Cryptosporidium spp. are leading etiologies of moderate-to-severe diarrhea in children worldwide,8 and neither responds to antimicrobial treatments. It has been estimated that 20–50% of all antimicrobial use is inappropriate.3 According to the WHO, only 40% primary care patients in the public sector and 30% of the patients in the private sector are treated following standard treatment guidelines with antimicrobials in developing and transitional countries.6,7,9 Antimicrobial use in treating diarrhea has also been excess of what is recommended by WHO guidelines. A recent study indicated that 76% of children less than 5 years of age from an urban site and 51% from a rural area received antimicrobial at home before reporting to the tertiary level hospital with diarrhea.10 In an ongoing birth cohort study among community-dwelling children in rural Mirzapur, Bangladesh, it was observed that there was a high prevalence of inappropriate use of antimicrobials in children older than 18 months (N = 262); among them 47% visited the hospital with the comorbidities in which 43% received antimicrobial before presentation to the hospital, and only 4% did not receive any antimicrobials. Among those who received antimicrobials, 43% of the children received them 1–5 times, and another 41% received antimicrobials 6–10 times during infancy and early childhood for minor ailments including fever, upper respiratory tract infection, and diarrhea. Factors contributing to antimicrobial overuse in children are parental knowledge and attitude, and physician’s belief in prescribing antimicrobial in daily practice.3,11–14

Studies from the International Center for Diarrheal disease research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) have demonstrated the evolution of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Shigella, a leading cause of severe invasive diarrhea2,4,10 and moreover, have found that patients with multidrug-resistant isolates of Shigella and Vibrio cholerae were more likely to experience severe disease, suggesting that AMR is not only difficult to treat, but may be associated with more severe clinical manifestations and poor outcomes.4,5,15

Antimicrobial resistance is an emerging public health threat, yet little is known about antimicrobial practices in rural lower income settings. In the present study, we aim to characterize antimicrobial usage at home and in health-care settings in pediatric patients in rural Bangladesh, with the goal of developing strategies to address antimicrobial overuse in these populations, and informing public health policy on antimicrobial guidelines and regulations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study site.

This study was conducted in Kumudini Women’s Medical College and Hospital, located in a rural community of Mirzapur subdistrict, Bangladesh, approximately 40 miles northwest of Dhaka, the capital city. The icddr,b established a Demographic Surveillance System (DSS) to collect longitudinal information on vital events, such as birth, death, marriage, and migration. The population size of the DSS was greater than 263,000 with 11% children under 5 years of age.16

Study design and participants.

From 2010 to 2012, a total of 3,570 children under 5 years of age with diarrhea, irrespective of gender and sociodemographic status were included in the study following a cross-sectional study design under the protocol (GR-00599) “Disease burden and etiology of diarrhea patients visiting Kumudini Hospital, Mirzapur.” A round-the-clock diarrheal disease surveillance system was established for the detection of four common pathogens: V. cholerae, Shigella, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, and rotavirus. Bacteria were cultured by standard methods and virus was isolated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) among diarrhea patients at Kumudini Hospital. Some children with diarrheal disease were treated as outpatients (977, 27%), whereas others required admission to the hospital (2,593, 73%). After consent was obtained from parents/guardians, a structured questionnaire was administered at the time of enrollment to mothers to collect information on demographics, epidemiologic factors, antimicrobial use before hospitalization and during hospitalization, and nutritional status and clinical characteristics in the pediatric ward for the inpatient or outpatient department. Anthropometric measurements were taken by field research assistants, and clinical examination was performed by a study physician.

Specimen collection and laboratory procedure.

A single, fresh, whole stool specimen (3–10 mL or grams) was collected from patients at enrollment. A fecal swab was collected and placed in Cary–Blair medium in a plastic screw top test tube and each specimen was packed and labeled with the subject’s identification number, date, and time of collection. Using a Styrofoam container with cold packs, the specimen was transported to the central laboratory of icddr,b Dhaka for isolation of rotavirus,17 V. cholerae,18 Shigella spp.,19 and enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC)18,20 following standard methods. For the detection of ETEC, fresh stool samples collected daily were plated onto MacConkey agar, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 hours. The detection of heat-labile toxin and heat-stable toxin was performed by ganglioside GM1 ELISAs. For detection of V. cholerae O1/O139, specimens collected in Cary–Blair were plated onto taurocholate-tellurite-gelatin agar. These plates were incubated aerobically at 35–37°C overnight. For isolation of Shigella spp., samples were primarily cultured on MacConkey. Serotyping was confirmed using serotyping antisera kit (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan) specific for all type- and group-factor antigens of Shigella species. Group A rotavirus antigen was detected using a commercially available kit (ProSpecT Rotavirus test, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) that uses a polyclonal antibody in a solid-phase sandwich enzyme immunoassay.

Ethical statement.

Approvals were obtained from the Research Review Committee and Ethical Review Committee of icddr, b. Informed written consent was obtained from the caregiver of each study child before enrollment.

Definitions.

Diarrhea and dysentery.

Diarrhea was defined as three or more loose, liquid, or watery stools. Dysentery was defined as at least one loose stool containing visible blood in a 24-hour period.

Moderate-to-severe disease.

Moderate-to-severe disease (MSD) was defined as the presence of one of the following characteristics21: 1) sunken eyes more than normal, 2) decreased skin elasticity, 3) intravenous rehydration administered or prescribed before coming to hospital, 4) dysentery, and 5) hospitalization with diarrhea or dysentery.

Mild disease (MD).

Children < 5 years old without any signs of MSD were considered as cases with MD.21–23

Fever.

Fever was considered as auxiliary temperature ≥ 37.8°C.

Antimicrobials misuse.

Use of antimicrobials when diarrhea was due to rotavirus.

Data analysis.

Statistical analyses and data entry were performed using Statistical Package for Social Science (version 20; SPSS, Chicago, IL) and Epi Info (Version 7.0; USD, Stone Mountain, GA). For categorical variables, differences in the proportions were compared by χ2 tests, and analyses of associations were examined using bi-variate analysis and calculation of the odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. A multivariate backward stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed with the probability of exclusion at P = 0.10 to identify the factors significantly associated with dependent variable. The covariates used in the model were child age, disease severity, distance of facility greater than 5 miles, duration of diarrhea, presence of blood in stool, vomiting, abdominal pain, rectal straining, cough, fever, use of oral rehydration solution (ORS), zinc and antimicrobial at home, antimicrobial misuse, and other etiologies of diarrhea (Shigella, V. cholerae, and rotavirus).

RESULTS

Study population.

A total of 3,570 children less than 5 years of age who visited a tertiary level hospital with diarrhea were enrolled. Among them 2,180 (61%) were male. Most were younger than 24 months of age (83%), and 17% were 25–59 months old. Sixty-two percent presented with moderate-to-severe diarrhea and 38% presented with mild diarrhea. The fathers’ occupation included overseas employment (21%), businessman (19%), farmer (17%), and skilled worker (12%). The mean household monthly income ± SD was 224.33 ± 314.71 USD (17,497.97 ± 24,547.48 Bangladeshi Taka).

Characteristics of children given antimicrobials at home.

Thirty-nine percent of children (N = 1,395) received antimicrobials at home before presentation at the hospital, and of these only 6% were prescribed the antimicrobials by a physician, the rest were purchased without any consultation with a physician. After presenting to the hospital, 84% (N = 2,993) of all children in the study were prescribed antimicrobials by an attending physician.

Children who were given antimicrobials at home were generally younger, had moderate-to-severe diarrhea, lived more than 5 miles away from a health-care facility, were given ORS at home, had more than 3 days of diarrhea, had more than 10 stools per day, and more often tested positive for rotavirus (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and etiological distribution of antimicrobials before hospital presentation among the under-five diarrheal children in rural Mirzapur (antimicrobial not dependent on the detection of pathogens)

| Variable | Used antimicrobial prior hospital; N = 1,395 (39%) | Not used antimicrobial prior hospital; N = 2,175 (61%) | OR (95% CI); P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age less than 24 months | 1,189 (85) | 1,758 (81) | 1.37 (1.14, 1.65); < 0.001 |

| Male gender | 864 (62) | 1,316 (61) | 1.06 (0.92, 1.22); 0.412 |

| Disease severity | |||

| Moderate-to-severe disease | 915 (41) | 1,317 (59) | 1.24 (1.08, 1.45); 0.003 |

| Mild disease | 450 (36) | 858 (64) | |

| Illiteracy of mother | 242 (17) | 360 (17) | 1.06 (0.88, 1.27); 0.566 |

| Distance of facility > 5 miles from residence | 675 (45) | 720 (35) | 2.46 (2.12, 2.83); < 0.001 |

| Monthly income > 128 US$ | 787 (56) | 1,272 (59) | 0.92 (0.80, 1.06); 0.236 |

| Zinc | 688 (49) | 390 (18) | 4.45 (3.82, 5.18); < 0.001 |

| Use of oral rehydration solution before coming to hospital | 1,309 (94) | 1,523 (70) | 6.52 (5.11, 8.32); < 0.001 |

| Stool consistency | |||

| Simple watery | 985 (71) | 1,386 (64) | 1.37 (1.18, 1.58); < 0.001 |

| Duration of diarrhea (> 3 days) | 536 (38) | 393 (18) | 2.83 (2.42, 3.31); < 0.001 |

| Frequency of stool > 10 times/24 hours | 696 (50) | 636 (29) | 2.41 (2.09, 2.78); < 0.001 |

| Vomiting | 853 (61) | 1,038 (48) | 1.72 (1.50, 1.98); < 0.001 |

| Cough | 593 (43) | 937 (43) | 0.98 (0.85, 1.12); 0.763 |

| Fever (≥ 37.8°C) | 656 (47) | 1,026 (47) | 0.99 (0.87, 1.14); 0.959 |

| Abdominal pain | 976 (70) | 1,443 (66) | 1.18 (1.02, 1.37); 0.026 |

| Blood in stool | 354 (25) | 717 (33) | 1.45 (1.24, 1.69); < 0.001 |

| Convulsion | 10 (1) | 46 (2) | 0.33 (0.16, 0.69); 0.002 |

| Rotavirus | 596 (43) | 550 (25) | 2.20 (1.90, 2.55); < 0.001 |

| Shigella | 162 (12) | 310 (15) | 0.79 (0.64, 0.97); 0.024 |

| Vibrio cholerae | 29 (2) | 34 (2) | 1.33 (0.79, 2.26); 0.319 |

| ETEC | 41 (3) | 91 (4) | 0.69 (0.47, 1.02); 0.064 |

CI = confidence interval; ETEC = enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli; OR = odds ratio.

The rate of antimicrobial misuse before hospital visit was 53% (N = 582/1,109); contrast, 82% (N = 905/1,109) incorrectly administered antimicrobials at hospital. Evaluating by pathogen, children with rotavirus diarrhea were more likely to receive antimicrobials at home than at the hospital (43% versus 25%, P < 0.001). Children with Shigella less often received antimicrobials at home than at the hospital (12% versus 15%, P = 0.024); and there was no difference in antimicrobial usage at home versus hospital in children with V. cholerae (2% versus 2%, P = 0.31) and ETEC (3% versus 4%, P = 0.06). Among the children with rotavirus diarrhea, children who lived further away from a facility, had longer duration and greater frequency of diarrhea, and presence of vomiting, were more likely to be given antimicrobials at home (Data not given).

Characteristics of children given antimicrobials by medical providers.

Of the 3,570 children enrolled in the study, 27% (N = 977/3,570) were treated as outpatients and 73% (N = 2,593/3,570) were admitted for medical care. Ninety-three percent (N = 911/977) of children seen as outpatients were given antimicrobials by physicians, and 80% (N = 2,082/2,593) of admitted children were given antimicrobials by their hospital physician. Of those admitted, 35% (N = 906) had mild diarrhea and 65% (N = 1,687) had moderate diarrhea. Twenty-seven percent tested positive for rotavirus, 12% for Shigella, 4% for ETEC, and 2% for V. cholerae. Seventy-four percent of children with rotavirus diarrhea were given antimicrobials after admission. Eighty-two percent of children were incorrectly administered antimicrobials at hospital. Children who were given antimicrobials during hospitalization were more likely to have a prior history of antimicrobial use at home, longer duration and greater frequency of diarrhea, cough, fever (≥ 37.8), abdominal pain, blood in stool, rectal straining, and stool testing positive for Shigella (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and etiological distribution of prescribed antimicrobials in the hospital for under-five diarrheal children in rural Mirzapur (antimicrobial not dependent on the detection of pathogens)

| Variable | Prescribed antimicrobial in the hospital; N = 2,993/3,570 (84%) | Not prescribed antimicrobial in the hospital; N = 577/3,570 (16%) | OR (95% CI); P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–24 months | 2,443 (82) | 504 (87) | 0.64 (0.49, 0.84); < 0.001 |

| Male gender | 1,832 (61) | 348 (60) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.25); 0.720 |

| Disease severity | |||

| Moderate-to-severe disease | 1,709 (77) | 523 (23) | 0.14 (0.10, 0.19); < 0.001 |

| Mild disease | 1,284 (96) | 54 (4) | |

| Illiteracy of mother | 517 (17) | 85 (15) | 1.21 (0.94, 1.56); 0.152 |

| Monthly income > 128 US$ | 1,745 (58) | 314 (54) | 1.17 (0.98, 1.41); 0.092 |

| Use of antimicrobials before hospital presentation | 1,220 (41) | 175 (30) | 1.58 (1.30, 1.92); < 0.001 |

| Duration of diarrhea (> 3 days) | 831 (28) | 98 (17) | 1.88 (1.48, 2.38); < 0.001 |

| Frequency of stool > 10 times/24 hours | 1,165 (39) | 167 (29) | 1.56 (1.28, 1.91); < 0.001 |

| Vomiting | 1,561 (52) | 330 (57) | 0.82 (0.68, 0.98); 0.030 |

| Cough | 1,287 (43) | 243 (42) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.25); 0.728 |

| Fever (≥ 37.8°C) | 1,474 (49) | 208 (36) | 1.72 (1.43, 2.08); < 0.001 |

| Abdominal pain | 2,115 (71) | 304 (53) | 2.16 (1.80, 2.60); < 0.001 |

| Blood in stool | 1,041 (35) | 30 (5) | 9.72 (6.59, 14.42); < 0.001 |

| Rectal straining | 1,471 (49) | 172 (30) | 2.28 (1.87, 2.77); < 0.001 |

| Convulsion | 50 (2) | 6 (1) | 1.62 (0.66, 4.21); 0.351 |

| Dehydration status (mild) | 2,713 (91) | 563 (98) | 0.24 (0.13, 0.42); < 0.001 |

| Rotavirus | 937 (31) | 209 (36) | 0.80 (0.66, 0.97); 0.023 |

| Shigella | 439 (15) | 33 (6) | 2.80 (1.91, 4.11); < 0.001 |

| Vibrio cholerae | 56 (2) | 7 (1) | 1.53 (0.67, 3.69); 0.374 |

| ETEC | 99 (3) | 33 (6) | 0.56 (0.36, 0.85); 0.006 |

CI = confidence interval; ETEC = enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli; OR = odds ratio.

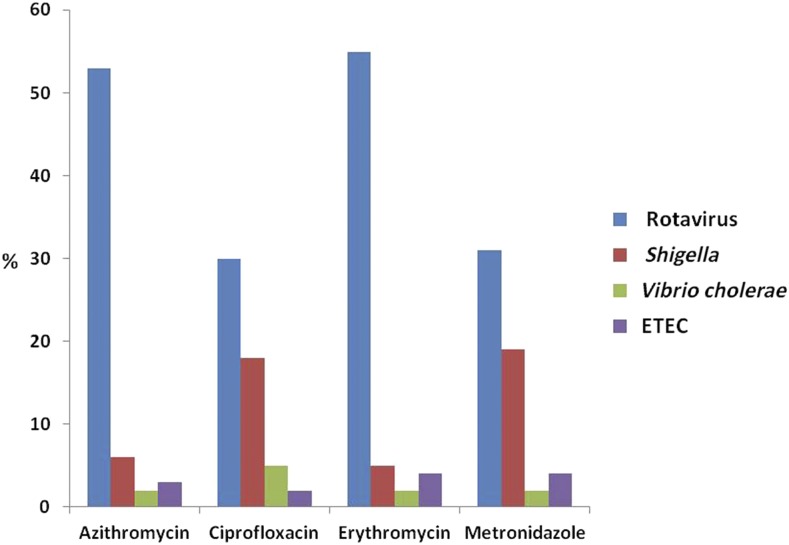

The use of azithromycin (N = 281; 53%) and erythromycin (N = 94; 55%) was more common in children with rotavirus diarrhea. In children with Shigella diarrhea, ciprofloxacin was used more commonly in the hospital versus at home before hospitalization (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathogen-specific use of antimicrobials before hospital presentation in percentage. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Risk factors for antimicrobial use.

In a multivariate regression analysis, children given antimicrobials at home were more likely to live more than 5 miles from a health-care facility; have zinc and ORS at home; have vomiting; have greater than 10 stools per 24 hours; have diarrhea longer than 3 days; and have infection with rotavirus (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate risk factors associated with antimicrobial use before hospitalization

| Indicator | Adjusted OR (95% CI); P value |

|---|---|

| Distance of facility > 5 miles from residence | 1.40 (1.20, 1.63); < 0.001 |

| Zinc (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 3.76 (2.92, 4.85); < 0.001 |

| Oral rehydration solution (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 2.81 (2.38, 3.32); < 0.001 |

| Vomiting (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 1.37 (1.16, 1.61); < 0.001 |

| Maximum no. of stool > 10 times/24 hours | 1.92 (1.64, 2.25); < 0.001 |

| Duration of diarrhea (> 3 days) | 2.72 (2.28, 3.24); < 0.001 |

| Rotavirus (1 = yes, 0 = no) | 1.61 (1.34, 1.92); < 0.001 |

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Dependent variable: 1 = used antimicrobials before hospitalization, 0 = not used antimicrobials before hospitalization.

Hospitalized children were more likely to be given antimicrobials if they had antimicrobial use before admission, fever, rectal straining, and tested positive for Shigella (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate risk factors associated with prescribed antimicrobials at hospital

| Indicator | Adjusted OR (95% CI); P value |

|---|---|

| Use of antimicrobials before hospital presentation | 1.39 (1.13, 1.71); < 0.001 |

| Fever (≥ 37.8°C) | 1.56 (1.29, 1.90); < 0.001 |

| Rectal straining | 1.76 (1.46, 2.12); < 0.001 |

| Shigella (1 = yes, no = 0) | 2.20 (1.51, 3.21); < 0.001 |

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Dependent variable: 1 = prescribed antimicrobial at hospital, 0 = not prescribed antimicrobial at hospital.

DISCUSSION

Inappropriate use of antimicrobials is an emerging public health concern in developing countries.10,22–24 The present study suggests that self-treatment at home with antimicrobials for diarrheal disease is common in rural Bangladesh, as 39% of children were given antimicrobials before hospitalization. There may be several contributing factors: easy access to pharmacy or drug stores with availability of frequently used low-cost antimicrobials and lack of regulation of sale of antimicrobials. Self-medication by mothers or primary caretakers may be common because of lack of adequate knowledge about the harmful effects of inappropriate antimicrobial use.25,26 A previous study from Bangladesh revealed that 27% of all medicines were sold without a prescription. Every 62 out of 100 prescriptions from quacks included an antibiotic. Of every 100 clients, 86 bought at least one antibiotic either because of a pharmacist’s recommendation or as self-medication. Moreover, 59% of pharmacies are operating without a valid and up-to-date license; 54% of drug vendors lack formal education in pharmaceutical science; and 62% never had any training in pharmacy from the government.27,28 These findings suggest there is much work needed to be completed in tackling the issues of drug administration, distribution, and control in developing countries such as Bangladesh. There is no current legislation that prohibits prescribing antimicrobials by unlicensed health-care providers, which allows for excess use of antimicrobials in Bangladesh.29

Greater distance from a hospital was clearly associated with increased frequency of home antimicrobial administration in children less than 5 years of age, as caregivers were more likely to seek medical care for their child at a nearby pharmacy when a hospital was not accessible. In rural Bangladesh, there are poor road conditions and a dearth of public transportation, creating a significant barrier to accessing medical care. Previous studies have even demonstrated that greater distance from health-care facilities was associated with a 50% decreased rate of immunization among children.22,23,29 Thus, distance, and lack of access to a health-care facility, must be viewed as an important determinant of improper antimicrobial use within communities.

An important observation of this study was the high rate of appropriate home administration of ORS and zinc for diarrheal illness in accordance with the WHO guidelines.30,31 Use of ORS in acute diarrhea repletes fluids and electrolytes, leads to decreased diarrhea mortality, and has been shown to reduce excess burden on health-care facilities at a community level. The Government of Bangladesh and nongovernmental organizations have promoted mass media campaigns to increase the general public’s awareness about the use of ORS and zinc in diarrheal illness.30,32–34 Our study demonstrates that there has been an uptake of these messages in the rural Mirzapur community, and these therapies are being appropriately administered at home.

This study is the first from South Asia to report that most of the rotavirus cases are inappropriately treated with antimicrobials both at home and by physicians in the hospital.34–36 In this study, physicians initiated empiric antimicrobial therapy before knowing the etiology of diarrhea because in our study the prescription was not based on the stool results. If physicians instead adhered to the WHO’s recommendations on empiric use of antibiotics, only in patients with bloody diarrhea and those suspected to have cholera with severe dehydration would have received empiric antibiotics. This highlights a need for physician education regarding appropriate use of antimicrobials in diarrheal disease in this region. In addition, antimicrobials were used more frequently in rotavirus diarrhea compared with other etiologies of diarrhea. This is likely because rotavirus was associated with increased duration and frequency of diarrhea and vomiting, leading to the perception of increased severity.

Severity of disease, real or perceived, appeared to drive inappropriate antimicrobial use, both at home and after hospitalization. Increased stool frequency, bloody stool, and vomiting were all associated with antimicrobials use at home. Likely, there is a lack of understanding among caregivers about the ineffectiveness of antimicrobials against viral illness. Perhaps just as media campaigns have increased awareness and education about ORS, similar efforts warning against the adverse effects of improper use of antimicrobials might be used to prevent antimicrobial misuse in the community.

Although medical professionals may be aware of antimicrobial ineffectiveness in diarrheal illness, they are driven by a desire to satisfy the patient or patient’s family.35,37,38 Physicians prescribed empiric antimicrobial for diarrhea based on clinical characteristics, such as rectal straining, visible bloody stool, and fever, despite lack of laboratory confirmation of the infectious agent. This suggests that the severity of illness triggers an aggressive treatment course by physicians. Unfortunately, this practice will continue to contribute to increased AMR in Bangladesh, where there are already reports of multidrug-resistant infections.39,40 Increasing awareness among both medical professionals and the public may alleviate the pressure to treat diarrhea with empiric antimicrobials.38,40,41 In addition, implementation of antimicrobial stewardship within hospitals may provide more formal guidance on appropriate antimicrobial use. Last, the WHO recommends prescribing antimicrobial for diarrheal disease only after determining the causative agent; however, diagnostic tests may be time-consuming or not readily available.7,9,31 Building capacity to improve rapid point-of-care diagnostics for diarrheal disease should be a high priority. In addition, as most children with moderate-to-severe diarrhea had rotavirus, improving rotavirus vaccine penetration rates both nationally and in the district studied would likely lead to less diarrhea cases and less inappropriate antimicrobial use more than any other intervention. Although Bangladesh has yet to introduce rotavirus vaccination, the country applied for Gavi support and plans to introduce it in 2018.

This study had several limitations. First, we did not have information on how many patients got appropriate antimicrobials at the hospital. Information collected based on mothers’ perceptions or reporting without observation at the household level might further add to our limitations. Data collected by using a questionnaire from the mother in observational conditions is truly a strong limitation in many medical studies. However, unbiased enrollment, irrespective of gender, nutritional status, disease severity, and socioeconomic background along with a large dataset with quality laboratory performance were the strengths of the current study.

In conclusion, our results highlight the remarkable misuse of antimicrobials at home and in a hospital setting in rural Bangladesh. Prescription of antimicrobials by physicians in the hospital did not comply with the WHO guidelines on treatment of diarrhea. There are several ways the government could aid in improving antimicrobial practices: 1) through stronger oversight of pharmacies and regulations requiring prescription by physician for antibiotic dispensing; 2) raising awareness about antimicrobial overuse among the general public; and 3) ensuring physicians are adhering to treatment guidelines. This study also highlights the urgent need for point-of-care diarrheal diagnostics for use at home or in a field clinic, which would allow early distinction between viral and bacterial etiologies, allowing for appropriate initial therapy and helping to limit antimicrobial overuse.

Acknowledgments:

This research protocol was funded by icddr,b’s core donors and Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida). International Center for Diarrheal disease research, Bangladesh acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) to its research efforts. International Center for Diarrheal disease research, Bangladesh also gratefully acknowledges the following donors who provide unrestricted support: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh; Global Affairs Canada (GAC); Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida); and the Department for International Development, (UKAid). Our heartfelt thanks also go to the Medical Director of Kumudini Women’s Medical College and Hospital for his sincere support to the research team. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) assisted with publication expenses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Principi N, Esposito S, 2016. Antimicrobial stewardship in paediatrics. BMC Infect Dis 16: 424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spellberg B, Guidos R, Gilbert D, Bradley J, Boucher HW, Scheld WM, Bartlett JG, Edwards J, Jr., 2008. The epidemic of antibiotic-resistant infections: a call to action for the medical community from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 46: 155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rousounidis A, Papaevangelou V, Hadjipanayis A, Panagakou S, Theodoridou M, Syrogiannopoulos G, Hadjichristodoulou C, 2011. Descriptive study on parents’ knowledge, attitudes and practices on antibiotic use and misuse in children with upper respiratory tract infections in Cyprus. Int J Environ Res Public Health 8: 3246–3262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay AD, 2010. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 340: c2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yagupsky P, 2006. Selection of antibiotic-resistant pathogens in the community. Pediatr Infect Dis J 25: 974–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holloway K, Van Dijk L, 2011. The World Medicines Situation 2011—Rational Use of Medicines. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization , 2013. Antimicrobial Use. Drug resistance. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- 8.Kotloff KL, et al. 2013. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 382: 209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization , 2014. Diarrhoea Treatment Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- 10.Ahmed S, Farzana FD, Ferdous F, Chisti MJ, Malek MA, Faruque ASG, Das SK, 2013. Urban-rural differentials in using antimicrobials at home among under-5 children with diarrhea. Sci J Clin Med 2: 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nyquist AC, Gonzales R, Steiner JF, Sande MA, 1998. Antibiotic prescribing for children with colds, upper respiratory tract infections, and bronchitis. JAMA 279: 875–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mangione-Smith R, McGlynn EA, Elliott MN, McDonald L, Franz CE, Kravitz RL, 2001. Parent expectations for antibiotics, physician-parent communication, and satisfaction. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 155: 800–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coco AS, Horst MA, Gambler AS, 2009. Trends in broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing for children with acute otitis media in the United States, 1998–2004. BMC Pediatr 9: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pechere JC, 2001. Patients’ interviews and misuse of antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis 33 (Suppl 3): S170–S173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sami AB, Islam M, Halim F, Akter N, Sadique T, Hossain MS, Elahi MSB, Hossain MA, Rahman MM, Ahmed D, 2015. Follow-up trends of bacterial etiology of diarrhoea and antimicrobial resistance in urban areas of Bangladesh. Avicenna J Clin Microbiol Infect 2: e32087. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed S, Ferdous F, Das J, Farzana F, Chisti M, 2015. Shigellosis among breastfed children: a facility based observational study in rural Bangladesh. J Gastrointest Dig Syst 5: 2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman M, De Leener K, Goegebuer T, Wollants E, Van der Donck I, Van Hoovels L, Van Ranst M, 2003. Genetic characterization of a novel, naturally occurring recombinant human G6P [6] rotavirus. J Clin Microbiol 41: 2088–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qadri F, Khan AI, Faruque ASG, Begum YA, Chowdhury F, Nair GB, Salam MA, Sack DA, Svennerholm A-M, 2005. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae diarrhea, Bangladesh, 2004. Emerg Infect Dis 11: 1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moyenuddin M, Rahman KM, Sack DA, 1987. The aetiology of diarrhoea in children at an urban hospital in Bangladesh. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 81: 299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qadri F, Das SK, Faruque A, Fuchs GJ, Albert MJ, Sack RB, Svennerholm A-M, 2000. Prevalence of toxin types and colonization factors in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated during a 2-year period from diarrheal patients in Bangladesh. J Clin Microbiol 38: 27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotloff KL, et al. 2012. The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) of diarrheal disease in infants and young children in developing countries: epidemiologic and clinical methods of the case/control study. Clin Infect Dis 55 (Suppl 4): S232–S245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferdous F, Ahmed S, Das SK, Farzana FD, Latham JR, Chisti MJ, Faruque AS, 2014. Aetiology and clinical features of dysentery in children aged < 5 years in rural Bangladesh. Epidemiol Infect 142: 90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferdous F, Das SK, Ahmed S, Farzana FD, Latham JR, Chisti MJ, Ud-Din AI, Azmi IJ, Talukder KA, Faruque AS, 2013. Severity of diarrhea and malnutrition among under five-year-old children in rural Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg 89: 223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chowdhury MA, 2012. Evolving antibiotic resistance: a great threat to medical practice. Bangladesh J Med Sci 11: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma M, Eriksson B, Marrone G, Dhaneria S, Lundborg CS, 2012. Antibiotic prescribing in two private sector hospitals; one teaching and one non-teaching: a cross-sectional study in Ujjain, India. BMC Infect Dis 12: 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmad A, Khan MU, Malik S, Mohanta GP, Parimalakrishnan S, Patel I, Dhingra S, 2016. Prescription patterns and appropriateness of antibiotics in the management of cough/cold and diarrhea in a rural tertiary care teaching hospital. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 8: 335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biswas M, Roy MN, Manik MI, Hossain MS, Tapu SM, Moniruzzaman M, Sultana S, 2014. Self medicated antibiotics in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional health survey conducted in the Rajshahi city. BMC Public Health 14: 847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saha S, Hossain MT, 2017. Evaluation of medicines dispensing pattern of private pharmacies in Rajshahi, Bangladesh. BMC Health Serv Res 17: 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Togoobaatar G, Ikeda N, Ali M, Sonomjamts M, Dashdemberel S, Mori R, Shibuya K, 2010. Survey of non-prescribed use of antibiotics for children in an urban community in Mongolia. Bull World Health Organ 88: 930–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roy SK, Hossain MJ, Khatun W, Chowdhury R, 2008. Zinc supplementation in children with cholera in Bangladesh: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 336: 266–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization , 2012. The Pursuit of Responsible Use of Medicines: Sharing and Learning from Country Experiences, Medicine. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

- 32.Onwukwe SC, 2014. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Mothers/Caregivers Regarding Oral Rehydration Therapy at Johan Heyns Community Health Center, Sedibeng District. Master’s Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lazzerini M, Wanzira H, 2016. Oral zinc for treating diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12: CD005436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter E, Bryce J, Perin J, Newby H, 2015. Harmful practices in the management of childhood diarrhea in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 15: 788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alkoshi S, Ernst K, Maimaiti N, Dahlui M, 2014. Rota viral infection: a significant disease burden to Libya. Iran J Public Health 43: 1356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ekwochi U, Chinawa JM, Obi I, Obu HA, Agwu S, 2013. Use and/or misuse of antibiotics in management of diarrhea among children in Enugu, southeast Nigeria. J Trop Pediatr 59: 314–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wongsaroj T, Thavornnunth J, Charanasri U, 1997. Study on the management of diarrhea in young children at community level in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai 80: 178–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rheinländer T, Samuelsen H, Dalsgaard A, Konradsen F, 2011. Perspectives on child diarrhoea management and health service use among ethnic minority caregivers in Vietnam. BMC Public Health 11: 690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gebeyehu E, Bantie L, Azage M, 2015. Inappropriate use of antibiotics and its associated factors among urban and rural communities of Bahir Dar city administration, northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One 10: e0138179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lina TT, Rahman SR, Gomes DJ, 2007. Multiple-antibiotic resistance mediated by plasmids and integrons in uropathogenic Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Bangladesh J Microbiol 24: 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Limaye D, Limaye V, Krause G, Fortwengel G, 2017. A systematic review of the literature on survey questionnaires to assess self-medication practices. Int J Community Med Public Health 4: 2620–2631. [Google Scholar]