Abstract.

We designed and implemented a survey of physician knowledge, attitudes, and practices with respect to Chagas disease in the state of Tabasco, Mexico. Seventy-eight public sector physicians from across the state responded via Research Electronic Data Capture, an online survey capture tool. Improved performance on knowledge-based questions (P < 0.01) and an increase in decisions to screen (P = 0.04) were associated with previous training specific to this disease. Our results provide important descriptive information regarding knowledge, attitudes, and practices among a group of public sector Mexican doctors and highlight the importance of Chagas disease–specific physician training for identification and, ultimately, treatment of patients affected by this disease.

INTRODUCTION

Chagas disease is a neglected tropical disease caused by the kinetoplast parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. It is spread to human hosts primarily by insects of the family Reduviidae in the Americas, with important secondary routes of spread via blood transfusion and congenital infection. Infection with the parasite is characterized by distinct phases: first, an acute phase of mild, nonspecific fever and malaise, with a minority of patients exhibiting identifiable swelling at the site of inoculation; second, an indeterminate phase, which is typically asymptomatic; and third, a chronic phase that occurs in up to 30% of infected persons that may result in cardiac arrhythmia, dilated cardiomyopathy, megaesophagus, or megacolon.1

An estimated 1.5–2 million people in Mexico are infected with T. cruzi as a result of T. cruzi endemicity and socioeconomic conditions promoting parasite spread.2 This prevalence is among the highest in the world, but despite the important burden posed by this disease, a small fraction of the estimated cases are diagnosed and even fewer are treated.3 Data from a public sector blood bank in Villahermosa, Tabasco’s capital city, show that 1.8% of donors had diagnostic levels of markers of T. cruzi infection in their blood. This seroprevalence is approximately four times the national average, and is among the highest rates in the country.4 This high prevalence may result from Tabasco’s ecologically permissive natural environment,2 as well as its geographical and populational relationship with Central America,5 another high-prevalence region.6

Important fronts of combat against this disease have included vector control and improved screening of blood supplies.7 In addition, surveys of laypeople in Mexico and other Latin American countries have helped to elucidate gaps and opportunities in population level understanding of the disease.8,9 The role of health-care providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices in endemic zones remains an important, but little researched, requirement for successful identification and treatment of Chagas disease. Although surveys of Mexican nurses10 and physicians in non-endemic countries have been conducted to assess preparedness,11,12 Mexican physicians’ status remains unknown.

Knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) surveys are a methodology to assess what individuals in a defined population know, believe, and report doing with regard to a particular subject and may collect both quantitative and qualitative information. Such surveys may aid the implementation of effective policies by making them responsive to educational needs, cultural beliefs, and behavior patterns.13

We developed a KAP instrument and surveyed Ministry of Health–employed physicians in the state of Tabasco to assess the current state of physician response to Chagas disease and identify strengths and opportunities for improvement.

METHODOLOGY

A KAP survey instrument was developed to assess the physician perspective of Chagas disease. Survey formatting and demography questions were based on a guide to KAP surveys developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Stop Tuberculosis Partnership,13 and knowledge questions were based on previous surveys of physician knowledge of Chagas disease.11,12

Comments were solicited from six experts with backgrounds in infectious disease, pediatrics, cardiology, and Chagas disease research. A round of pretesting13 was conducted among physicians of various specialties at a Mexican university, with face-to-face feedback. A pilot study was conducted among family medicine residents at a hospital in Mexico City to ensure the reliability of logistical aspects of the survey.

Surveys were shared via a link unique to each surveyed physician via the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) online survey platform.14 The survey was open for 1 month in March to April of 2017, with daily automated reminders sent through the REDCap platform to respondents who had not yet completed the survey. Survey respondents were automatically directed to a Spanish-language WHO informational page on completion of the survey.15 Data analysis was performed using the statistical software package R.16

Ethical approval of the protocol was obtained from the Tabasco Ministry of Health Office of Health Quality and Education (INV/2314/PCI/1116) and the University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division institutional review board (IRB16-1607). Informed consent was obtained at the outset of the electronic survey.

RESULTS

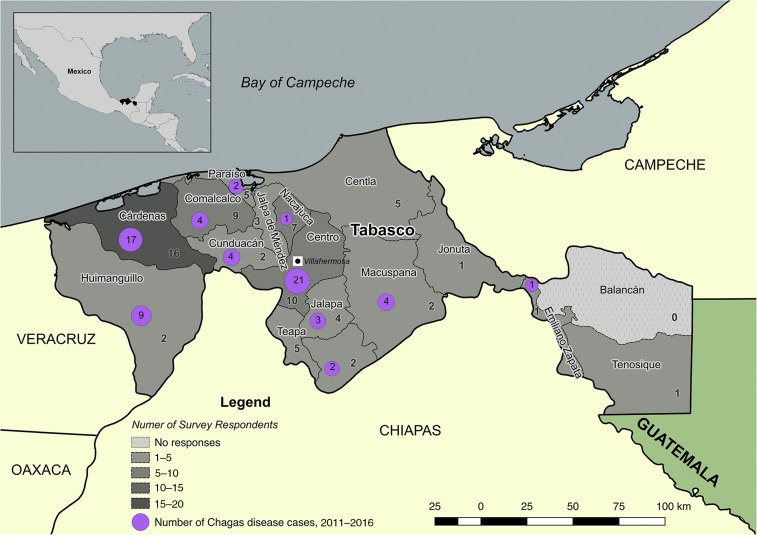

The Tabasco Ministry of Health provided 293 valid, unique e-mail addresses for physicians associated with the 17 municipal health jurisdictions in Tabasco (Figure 1). Ninety-one responses were received (31.1% raw response rate), including respondents from all jurisdictions with the exception of Balancán. Two persons identified that they were not physicians in screening questions and were omitted. Eleven surveys were invalidated as the respondents did not provide answers past the demographic section.

Figure 1.

Map of the study region showing number of responses per jurisdiction and number of Chagas disease cases reported to the national Ministry of Health during 2011–2016 time frame. Chagas disease case data from the Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Seventy-eight responses were analyzed (26.6% valid response rate) and descriptive results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Tabasco physicians’ responses to the Chagas disease knowledge, attitudes, and practices survey

| Demographics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total responses | 91 | Patient age group | |

| Valid Responses | 78 (87.9%)* | Adults | 25 (32.1%) |

| Specialty | Children | 1 (1.3%) | |

| Primary care | 54 (69.2%) | Both | 52 (66.7%) |

| Internal/general medicine | 8 (10.3%) | Years of experience (years) | |

| Epidemiology/public health | 4 (5.1%) | < 1† | 36 (46.2%) |

| Obstetrics/gynecology | 4 (5.1%) | 1–3 | 4 (5.1%) |

| Infectious diseases | 3 (3.8%) | 3–10 | 19 (24.4%) |

| Emergency medicine | 1 (1.3%) | 10–20 | 10 (12.8%) |

| Chronic diseases | 1 (1.3%) | 20–30 | 8 (10.3%0 |

| Geriatrics | 1 (1.3%) | > 30 | 1 (1.3%) |

| Administration | 1 (1.3%) | ||

| Knowledge | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you heard of CD? | Yes | No | ||

| 78 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| What type of microorganism causes CD? | Correct | Incorrect | ||

| 76 (97.4%) | 2 (2.6%) | |||

| What are the symptoms of infection by the microorganism that causes CD? | Correct | Incorrect | ||

| 32 (41.6%) | 45 (58.4%) | |||

| How do the symptoms of CD present chronologically? | Correct | Incorrect | ||

| 37 (48.1%) | 40 (51.9%) | |||

| What medication(s) are indicated for the treatment of CD? (out of two correct answers) | 2/2 Correct | 1/2 Correct | Incorrect | |

| 0 (0%) | 46 (59.0%) | 32 (41.0%) | ||

| How is CD transmitted? (out of three correct answers) | 3/3 Correct | 2/3 Correct | 1/3 Correct | Incorrect |

| 37 (47.4%) | 10 (12.8%) | 29 (37.2%) | 2 (2.6%) | |

| Attitudes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In your opinion, how serious is CD? | Not serious | Somewhat serious | Serious | Very serious | Extremely serious |

| 0 (0%) | 3 (3.9%) | 35 (46.1%) | 29 (38.2%) | 9 (11.8%) | |

| In your opinion, how common is CD in the region where you work? | Not common | Somewhat common | Common | Very common | Extremely common |

| 27 (35.5%) | 39 (51.3%) | 8 (10.5%) | 2 (2.6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| How prepared do you feel to diagnose CD? | Unprepared | Somewhat prepared | Prepared | Very prepared | Extremely prepared |

| 6 (8.0%) | 38 (50.7%) | 29 (38.7%) | 2 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| How prepared do you feel to screen for CD? | Unprepared | Somewhat prepared | Prepared | Very prepared | Extremely prepared |

| 7 (9.3%) | 43 (57.3%) | 23 (30.1%) | 2 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Practices | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How frequently do you consider the diagnosis of CD? | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Frequently | Almost always |

| 22 (29.3%) | 42 (56%) | 11 (14.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| How frequently do you ask patients if they do or have lived in places or conditions favorable to the transmission of CD? | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Frequently | Almost always |

| 18 (24.3%) | 23 (31.1%) | 14 (18.9%) | 16 (21.6%) | 3 (4.1%) | |

CD = Chagas disease.

Responses were considered valid if at least a portion of the knowledge, attitude, and practices sections of the survey was completed; all subsequent percentages are of the number who answered that individual question.

Includes those performing nationally mandated social service years.

Knowledge of basic clinical aspects of Chagas disease and screening practices were noted to differ by whether respondents had a history of previous training specifically directed at Chagas disease (P < 0.01), with higher mean knowledge scores and increased likelihood of screening (P = 0.04) (Figure 2). No statistical difference in knowledge was noted based on length of medical practice (P = 0.50) or level of confidence regarding knowledge of Chagas disease (P = 0.85).

Figure 2.

Impact of training history on physician knowledge and practices. (A) A history of training specific to the diagnosis or screening of Chagas disease was associated with statistically significant higher scores. Experience and confidence levels were not associated with statistically different scores. (B) Percentage of respondents with and without previous Chagas disease–specific training who would screen patients under various scenarios. A significantly higher rate of positive responses to screening was seen among physicians who reported previous training. Patient scenarios are coded as follows: (+) screening is specifically indicated by national guidelines 16–18; (±) screening is not specifically mandated by guidelines but may be clinically indicated; (−) screening is not clinically indicated. *Student’s t test of means. †Pearson’s χ2.

In response to questions regarding installed capacity for relevant clinical tests, respondents were asked about their access to tests defined by the national Secretary of Health’s Chagas Disease Diagnosis and Treatment Manual—smear, microhematocrit, Strout technique, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, indirect immunofluorescence, indirect hemagglutination, Western blot, and polymerase chain reaction17—both in their clinic and by referral to another laboratory. In their own clinics, 24 (33.3%) reported access to no tests, 28 (38.9%) to one test, and 20 (27.8%) to more than one. As a send-out test, 6 (8.3%) reported access to no tests, 23 (31.9%) to one test, and 43 (59.8%) had access to more than one. Nine (12.5%) respondents reported that electrocardiography was available to them in their place of work and 3 (4.2%) had access to echocardiography.

DISCUSSION

Appropriate recognition and response to Chagas disease remains a clinical challenge, including in endemic regions. Our results highlight the importance of disease-specific training in shaping physician knowledge and practices with regard to Chagas disease.

It is important to note that in our results, training was associated with a significant increase in reported screening practices, even among patients in whom it is not indicated, underlining the necessity for future training programs to clearly define risk factors.

Relative knowledge levels, as measured by questions adapted from previously reported surveys, were higher in our surveyed group than in physicians in the United States,11,12,18,19 possibly because of greater educational emphasis20 and case experience among physicians within the disease’s endemic range. All surveyed doctors had heard of the disease and > 97% knew it to be parasitic. However, basic misconceptions regarding Chagas disease were prevalent, particularly with regard to treatment modalities and the spectrum of symptoms, a result that echoes findings in a previous survey of Mexico City blood bank nurses.10 Benchmarking of our results against those of other endemic areas in Mexico or elsewhere is not currently possible as comparable physician surveys have not been reported.

Physicians’ attitudes indicated that Chagas disease is considered a “serious,” rather than a “common,” disease. This perception of Chagas disease as an abstract threat may contribute to the discrepancy between estimated case burden and prevalence of confirmed disease. In addition, most physicians considered themselves to be “somewhat prepared” or “unprepared” for diagnosing or screening for the disease. These attitudes may impact practices, potentially accounting for most physicians in our sample who “rarely” or “never” consider the diagnosis of Chagas disease or ask about past or current exposure to conditions related to the disease’s spread.

The results of our survey should be considered in light of certain limitations. First, we surveyed a relatively small and geographically specific population of public sector physicians of a single Mexican state. Some results may speak to the particular situation of this profession, geography, or healthcare system. The skew of respondents toward relatively new practitioners (46.2% were in their first year of practice) likely represents the important role of Mexico’s mandatory “social service” year for medical school graduates in providing primary care to rural populations, including more than 200 practitioners per year in Tabasco.22 Second, certain jurisdictions are known to have more limited internet access than others, potentially accounting for geographic differences in response rate. Future studies may benefit from physical or in- person survey modalities. Finally, our response rate was similar to that of other email surveys administered to medical providers,21 but does imply that many invited subjects did not respond.

An important area of future attention will be comparing and assessing training and education types for the promotion of desired knowledge and behaviors among physicians, as this study did not attempt quantitative or qualitative appraisal of the reported training. Although this represents a limitation of the data gathered by the survey instrument, we consider it to be fertile ground for educators, researchers, and public health officials interested in medical education and quality improvement research in this geographic or subject area.

Finally, it must be emphasized that physician knowledge, attitudes, and practices are just one aspect of a health system’s capability to improve diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease. Systemic and institutional capacity, such as laboratory testing and drug purchasing, must be developed in parallel.3 Recent national guidelines have sought to address such systemic shortcomings,17,23 although patient-level impact will be dependent on implementation and continued progress of these new policies.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Julissa Acevedo, Miroslava Avila García, Ingeborg Becker, Fanny Fabiola Zapata Custodio, Maria Guadalupe Fernandez Vargas, Ricardo Figueroa, Ramon Izquierdo Arce, Javier Mancilla Ramírez, Esther Ocharan Hernandez, Arturo Revuelta Herrera, Cesar Rivera Benitez, Emma Saavedra, the Tabasco health jurisdiction authorities, and all who answered the survey.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, Jannin J, de Boer M, 2012. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One 7: e35671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramsey JM, Townsend Peterson A, Carmona-Castro O, Moo-Llanes DA, Nakazawa Y, Butrick M, Tun-Ku E, de la Cruz-Félix K, Ibarra-Cerdeña CN, 2015. Atlas of Mexican Triatominae (Reduviidae: Hemiptera) and vector transmission of Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 110: 339–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manne JM, Snively CS, Ramsey JM, Salgado MO, Bärnighausen T, Reich MR, 2013. Barriers to treatment access for Chagas disease in Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novelo Garza BA, Benítez Arvizu G, Peña Benítez A, Galván Cervantes J, Morales Rojas A, 2010. Detección de Tripanosoma cruzi en donadores de sangre. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 48: 139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isacson A, Meyer M, Morales G, 2014. Mexico’s Other Border: Security, Migration, and the Humanitarian Crisis at the Line with Central America Washington, DC: WOLA. Available at: https://www.wola.org/sites/default/files/WOLA_The Other Border Publication.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2018.

- 6.Stanaway JD, Roth G, 2015. The burden of Chagas disease: estimates and challenges. Glob Heart 10: 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumonteil E, Herrera C, Gurgel-Goncalves R, Gurtler R, Schijman A, 2017. Ten years of Chagas disease research: looking back to achievements, looking ahead to challenges. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11: e0005422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosecrans K, Cruz-Martin G, King A, Dumonteil E, 2014. Opportunities for improved Chagas disease vector control based on knowledge, attitudes and practices of communities in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8: e2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabrera R, Mayo C, Suárez N, Infante C, Náquira C, García-Zapata M, 2003. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices concerning Chagas disease in schoolchildren from an endemic area in Peru. Cad Saude Publica 19: 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trivedi M, Sanghavi D, 2010. Knowledge deficits regarding Chagas disease may place Mexico’s blood supply at risk. Transfus Apheresis Sci 43: 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verani JR, Montgomery SP, Schulkin J, Anderson B, Jones JL, 2010. Survey of obstetrician-gynecologists in the United States about Chagas disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg 83: 891–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stimpert KK, Montgomery SP, 2010. Physician awareness of Chagas disease, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 16: 871–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization, Stop TB Partnership , 2008. Advocacy, Communication and Social Mobilization for TB Control: a Guide to Developing Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Surveys Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43790. Accessed April 9, 2018.

- 14.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG, 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization , 2017. La Enfermedad de Chagas (tripanosomiasis americana) Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs340/es/. Accessed June 17, 2017.

- 16.R Core Team , 2016. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing Available at: https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed April 8, 2018.

- 17.Secretaría de Salud , 2015. Manual de Diagnóstico Y Tratamiento de La Enfermedad de Chagas Ciudad de México, México: Secretaría de Salud. Available at https://www.gob.mx/salud/documentos/manual-de-diagnostico-y-tratamiento-de-la-enfermedad-de-chagas. Accessed April 8, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amstutz-Szalay S, 2017. Physician knowledge of Chagas disease in Hispanic immigrants living in appalachian Ohio. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 4: 523–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parise ME, Dotson EM, Bialek SR, Montgomery SP, 2016. What do we know about Chagas disease in the United States? Am J Trop Med Hyg 95: 1225–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Errea RA, et al. Medical student knowledge of neglected tropical diseases in Peru: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9: e0004197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, Noseworthy T, Beck CA, Dixon E, Samuel S, Ghali WA, Sykes LL, Jetté N, 2015. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 15: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendoza EM, Sánchez MC, 2014. Servicio social de medicina en el primer nivel de atención médica: de la elección a la práctica. Rev Educ Super 43: 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Secretaría de Salud , 2015. Programa de Acción Específico: Prevención Y Control de La Enfermedad de Chagas 2013–2018 Ciudad de México, México: Secretaría de Salud. Available at: http://www.cenaprece.salud.gob.mx/descargas/pdf/PAE_PrevencionControlEnfermedadChagas2013_2018.pdf. Accessed April 8, 2018.