Abstract

The development of a reliable platform for the electrochemical characterization of a redox-active molecular diiron complex, [FeFe], immobilized in a non-conducting metal organic framework (MOF), UiO-66, based on glassy-carbon electrodes is reported. Voltammetric data with appreciable current responses can be obtained by the use of multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) or mesoporous carbon (CB) additives that function as conductive scaffolds to interface the MOF crystals in “three-dimensional” electrodes. In the investigated UiO-66-[FeFe] sample, the low abundance of [FeFe] in the MOF and the intrinsic insulating properties of UiO-66 prevent charge transport through the framework, and consequently, only [FeFe] units that are in direct physical contact with the electrode material are electrochemically addressable.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are three-dimensional coordination polymers with high internal surface areas. Due to their intrinsic topology and porosity,1 they have been studied for applications in gas storage/separation,2–5 chemical sensing,6 and drug delivery.7 Unlike other porous materials such as zeolites, the organic ligand component of MOFs allows for functionalization of internal channels and/or cavities either through direct solvothermal synthesis,8 or by postsynthetic modification reactions that include the metathesis of metal ions and organic linkers under relatively mild conditions.9, 10

The notion that the interior of MOFs can be tailored for a specific catalytic reaction has brought forward the vision of artificial enzymes. 11, 12 In this context, MOFs have emerged as appealing platforms for the incorporation of organometallic catalysts of energy relevance, i.e. water oxidation and proton and CO2 reduction catalysts. These materials are particularly appealing in context of artificial photosynthesis.13 For example, Lin et al. reported the solvothermal incorporation of Ir and Re complexes into MOFs as catalysts for CeIV-promoted water oxidation14 and photochemical CO2 reduction,15 respectively. Ourselves, we used a post-synthetic exchange methodology to introduce a thermally labile hydrogen evolution catalyst into a MOF.16 These and related recent reports from other labs17–21 share in common that the structural stability of the catalyst is enhanced by MOF incorporation, giving rise to higher turnover numbers as compared to the same catalyst in homogenous solution phase. Much less attention has been paid to the influence of the MOF matrix on the thermodynamic characteristics of the catalysts. For example, there is only very sporadic data in the literature of voltammetrically characterized organometallic catalysts in MOFs. In general, the acquisition of cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of MOF-incorporated catalysts is complicated by the fact that most MOFs are intrinsically non-conducting.22 With catalyst loadings of less than 10 % of all linkers, as in many of the examples above, the acquisition of voltammetric information is hampered by very low current responses, in particular under non-turnover conditions. Example in which these problems have been circumvented include platforms based on graphene-MOF composites23 or by growing24–27 or electrophoretically depositing28, 29 MOFs directly onto electrode materials, often conducting metal oxides. MOFs in which 100 % of the linkers are at the same time catalytically active are less problematic in this regard as the close proximity of the catalysts facilitates charge transport into the interior of the MOF crystals and thus appreciable current responses. Examples for this scenario are a metallated derivative of MOF-52529 and the [Al2(OH)2TCPP-Co].30

The goal of the present work was to develop an easy to use platform that allows the routine electrochemical characterization of catalysts that are contained with low loading in bulk-prepared, non-conducting MOFs. Also, the electrode materials need to be based on carbon due to its advantageous stability under reductive conditions and in the presence of protons as compared to metal oxide electrodes.31

The platform development was done on a Zr(IV)-based UiO-66 framework into which a dinuclear iron complex, [Fe2(dcbdt)(CO)6] ([FeFe], dcbdt = 1,4-dicarboxylbenzene-2,3-dithiolate), has been incorporated (Figure S1).16 The UiO-66-[FeFe] fulfils the criteria of a challenging material to be analysed electrochemically due to a relatively low [FeFe] loading (about 15 %) as well as the insulating properties of UiO-type MOFs. 25, 27 25, 27 25, 27

Background CVs were first recorded for pristine UiO-6632 crystals that had been drop-casted as a suspension onto a glassy carbon surface (GC, geometrical area 0.38 cm2).33, 34 The UiO-66 crystals maintain their particle size and crystallinity during the procedure, and form films that are best described as relatively homogenous crystal mono-layers with some degree of aggregation. The overall surface coverage is circa 30% (Figure S2 and S3). Unmodified UiO-66 films are electrochemically inactive in the potential window from 0.0 V to -1.7 V vs. Ag+/0 (all potentials are reported against Ag/AgNO3, 10 mM in CH3CN) due to the absence of redox-active moieties in UiO-66 (Figure S4).

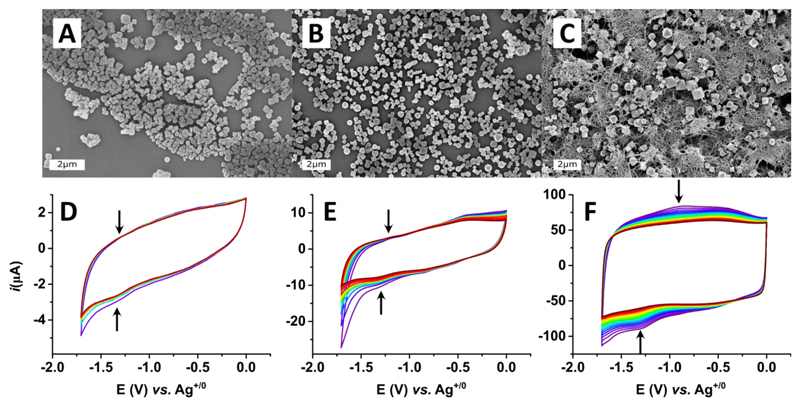

GC electrodes modified with UiO-66-[FeFe] by the same procedure show an extremely weak cathodic feature at circa - 1.30 V (Figure 1D) which is reminiscent to the quasi-reversible two-electron reduction at E1/2= -1.13 V observed on FTO conducting glass in DMF solution.25 The weak electrochemical response in these electrodes can be attributed to following factors: a low surface coverage, a potentially poor electronic coupling between electrode surface and MOF, the relatively low incorporation of Fe2(dcbdt)(CO)6 within UiO-6616 with the associated low abundance at the GC-UiO-66 interface, and finally the non-conductive nature of UiO-66 which prevents electron transfer into the bulk of the UiO-66-[FeFe].

Figure 1.

Top-view SEM images of (A) GC-UiO66[FeFe] (B) GC-PAA-UiO66[FeFe] and (C) GC-MWCNT-PAA-UiO66[FeFe] modified electrodes and their respective progressive cyclic voltammograms (purple to red) showing gradual decrease in signal intensity over scanning (D, E and F, respectively). The voltammograms were recorded in acetonitrile (n-Bu4NPF6 0.1 M) at ν= 100 mVs-1 under Ar using a non-aqueous Ag/AgNO3 (10 mM) reference electrode.

In order to improve the electrode coverage and the electrical contact between the conductive surface (GC) and the UiO-66-[FeFe] crystals, 1-pyreneacetic acid (PAA) was used as anchoring group. The Zr6O4(OH)4 clusters situated at the surface of the UiO-66-[FeFe] crystals are coordinated by the carboxylate group of PAA, while the pyrenyl group adsorbs to the GC surface through π–π interactions (Figure S6). As shown in the SEM images in Figure 1B, the anchoring groups result in a more homogenous distribution of UiO-66-[FeFe] crystals and an increased surface coverage of ca. 50% of the total electrode area (Figure S3). Consequently, the electrochemical response of the GC-PAA-UiO-66-[FeFe] electrodes is improved compared to that of GC-UiO-66-[FeFe]. CVs of these electrodes (Figure 1E) show a more defined cathodic feature at -1.25 V. An additional cathodic and anodic feature at -0.86 V and -0.39 V, respectively, can be observed in the CVs of GC-PAA-UiO-66-[FeFe] and is assigned to the PAA linker by comparison with solution data (Figure S7). Notably, peak currents associated with the [FeFe] complex decrease with consecutive scans, suggesting a loss of the absorbed MOF or degradation of the catalyst. SEM images showed no apparent depletion of PAA-UiO-66-[FeFe] after the CVs, suggesting catalyst degradation under recording of non-catalytic CVs.

The next attempt to obtain a decent voltammetric response involved the contacting in “3D” electrodes using the GC electrodes with identical geometric surface area, but significantly larger conductive surface area. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) are particularly attractive for this purpose due to their high surface area along with their excellent conductive properties. Strong π–π interactions between pyrenyl groups and the carbon nanotubes are well documented.35–37 Thus, PAA-UiO-66-[FeFe] was dispersed in a MWCNT suspension and the resulting MWCNT-PAA-UiO-66-[FeFe] assemblies were coated on GC electrodes. SEM analysis confirms full coverage of the GC surface (Figure 1C). Higher magnification SEM images show that the MOF crystals are embedded in the elaborate nanotube scaffold (Figure S8).

CVs of MWCNT-PAA-UiO66[FeFe] electrodes show clear signals that originate from the incorporated [FeFe] complex (Figure 1F). Similar to GC-PAA-UiO-66-[FeFe], a decrease of the reductive peak current was also observed for the MWCNT-PAA-UiO-66-[FeFe] material. Peak potentials at -1.30 V and -0.90 V were determined for the cathodic and anodic processes, respectively, giving rise to a formal E1/2 = -1.10 V for the catalyst inside the UiO-66 with a ΔEp ˜ 400 mV. The large ΔEp and peak broadening can be attributed to the large internal resistance in the MOF. The charging current observed in these CVs is ascribed to the double-layer capacitance of the MWCNTs with very high specific surface area. As expected, signals for PAA were observed at -0.86 V and -0.44 V also in MWCNT-PAA-UiO-66-[FeFe].

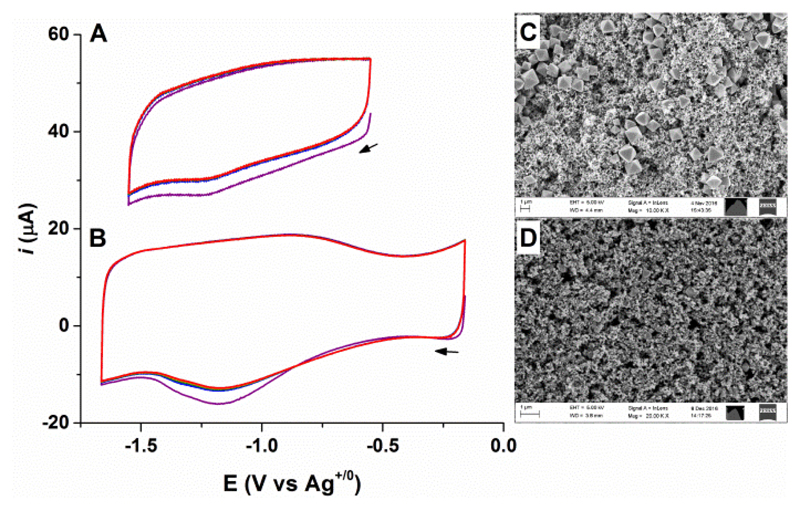

Building upon the design principle of “3D” electrodes, the MOF crystals were interfaced with carbon black (CB, particle size < 500 nm) to produce an ink which was subsequently drop-casted on GC electrodes. Two different CB:MOF weight ratios, 1:2 and 4:1 (denoted by GC-CB-UiO-66-[FeFe]1:2 and GC-CB-UiO-66-[FeFe]4:1, respectively) were used to optimize the electrochemical response of UiO-66-[FeFe]. SEM images of the electrodes show that increasing the weight percentage of CB from 33% to 80% led to full coverage of the GC surface. In these electrodes, especially GC-CB-UiO-66-[FeFe]4:1, the MOF crystals were completely embedded inside the mesoporous carbon network (Figure 2D) leading to greater connectivity with the conductive surface.

Figure 2.

Progressive cyclic voltammograms of (A) GC-CB-UiO-66-[FeFe]1:2 and (B) GC-CB-UiO-66-[FeFe]4:1 electrodes (scan 1–6: colour coded as purple, blue, olive, yellow, orange, and red), and their top-view SEM images (C and D, respectively). CVs recorded in acetonitrile (n-Bu4NPF6 0.1 M) at ν= 100 mVs-1 under Ar using a non-aqueous Ag/AgNO3 (10 mM) reference electrode. The y-axis is offset by 40 μA (A) for clarity.

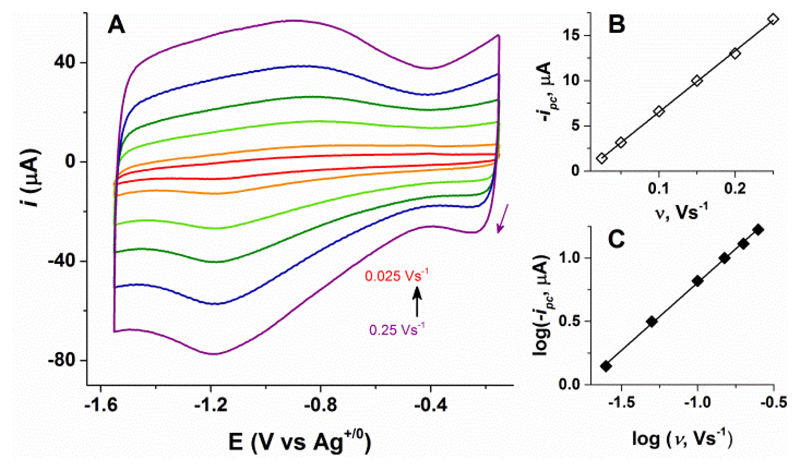

As shown in Figure 2, CVs of the GC-CB-UiO-66-[FeFe] electrodes reveal a quasi-reversible reduction process with corresponding to the [FeFe]-complex in the MOF. The control experiments with unmodified parent UiO-66 are shown in Figure S9 which confirms that the reductive peak at -1.2 V originates from the MOF-bound [FeFe]-complex. The best current response was obtained for the GC-CB-UiO-66-[FeFe]4:1 electrodes, which in contrast to the MWCNT and PAA based platforms also retained constant peak currents over successive scans. This stability allows probing the scan rate dependence and charge-transport behaviour of UiO-66-[FeFe]. For an intrinsically non-conducting UiO-type MOF, the electrochemical response can originate either from the [FeFe] molecules residing at the interface between the electrode surface and the MOF crystals, or from charge propagation via electron hopping between redox-active sites leading to diffusion controlled currents.26, 27, 38 The peak current (ip) should vary linearly with scan rate (ν) in the first scenario, whereas ip should be proportional to ν1/2 for the diffusion controlled process which involves transport of counterions inside MOF pores.26, 39 As shown in Figure 3, the reductive peak current for the Faradaic process (ip)40 varies linearly with scan rate (ν), consistent with surface confined redox processes. This assignment is further supported by the double logarithmic analysis of the data which shows that a plot of log (ip) vs. log (ν) has the slope of 1.06 (Figure 3C), suggesting only the surface bound [FeFe]-sites in direct contact with the electrode undergo reduction and the bulk MOF material remains unaffected. Maximizing the contact area between the crystals and the conductive surface via carbon networks (MWCNT and CB) is therefore essential to record CVs with appreciable current response.

Figure 3.

(A) Cyclic voltammograms of GC-CB-UiO-66-[FeFe]4:1 recorded at different scan rates (0.25 Vs-1: purple, 0.20 Vs-1: blue, 0.15 Vs-1: olive, 0.10 Vs-1: pale green, 0.05 Vs-1: orange, 0.025 Vs-1: red). (B) Linear dependence of ip on ν. (C) Log (-ip) versus log (ν) plot with a slope of 1.06.

In summary, we have investigated two- and three-dimensional electrode platforms for the acquisition of electrochemical data of molecular species incorporated in non-conductive MOFs. All methods are readily applicable for bulk-prepared MOFs without the need for growing them directly onto electrode surfaces. While CVs in the two-dimensional platforms were plagued by poor current responses, the use of MWCNT and carbon black as three-dimensional matrices allows the determination of electrochemical parameters for incorporated redox-active species. Scan-rate depended CVs show that only species that are in direct contact with the electrode material are electrochemically addressable. Secondary charge transport into the interior of the MOFs, for example through a hopping mechanism,29, 38, 41 is not operating due to the insulating nature of UiO-66 and the large distance between [FeFe] sites in the MOF. The 3D electrodes for the routine measurement of voltammetric data of catalyst-containing bulk MOFs that we report herein are an analytical tool to investigate the effect that the MOF matrix has on the catalysts’ electrochemical properties. We foresee that such tools will become increasingly important in future studies where the interior of MOF pores will be tailor-made to interact with the catalysts to improve their performance, i.e. the vision of MOF-based artificial enzymes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Energy Agency, the Knut & Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Wenner-Gren Foundations (postdoctoral stipend to S. R.), and the European Research Council (ERC-CoG2015-681895_MOFcat). Prof. Seth Cohen (UCSD) and Prof. Leif Hammarström (UU) are acknowledged for valuable discussions.

Notes and References

- 1.O'Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Chem Rev. 2012;112:675–702. doi: 10.1021/cr200205j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sumida K, Rogow DL, Mason JA, McDonald TM, Bloch ED, Herm ZR, Bae T-H, Long JR. Chem Rev. 2012;112:724–781. doi: 10.1021/cr2003272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowsell JLC, Yaghi OM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:4670–4679. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Férey G, Mellot-Draznieks C, Serre C, Millange F, Dutour J, Surblé S, Margiolaki I. Science. 2005;309:2040–2042. doi: 10.1126/science.1116275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosi NL, Eckert J, Eddaoudi M, Vodak DT, Kim J, O'Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Science. 2003;300:1127–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.1083440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreno LE, Leong K, Farha OK, Allendorf M, Van Duyne RP, Hupp JT. Chem Rev. 2012;112:1105–1125. doi: 10.1021/cr200324t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rocca JD, Liu D, Lin W. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:957–968. doi: 10.1021/ar200028a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eddaoudi M, Kim J, Rosi N, Vodak D, Wachter J, O'Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Science. 2002;295:469–472. doi: 10.1126/science.1067208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen SM. Chem Rev. 2012;112:970–1000. doi: 10.1021/cr200179u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deria P, Mondloch JE, Karagiaridi O, Bury W, Hupp JT, Farha OK. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:5896–5912. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00067f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang M, Gu Z-Y, Bosch M, Perry Z, Zhou H-C. Coord Chem Rev. 2015;293–294:327–356. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen SM, Zhang Z, Boissonnault JA. Inorg Chem. 2016;55:7281–7290. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b00828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang T, Lin W. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:5982–5993. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00103f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Wang JL, Lin W. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:19895–19908. doi: 10.1021/ja310074j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Xie Z, deKrafft KE, Lin W. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:13445–13554. doi: 10.1021/ja203564w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pullen S, Fei H, Orthaber A, Cohen SM, Ott S. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16997–17003. doi: 10.1021/ja407176p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nepal B, Das S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:7224–7227. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasan K, Lin Q, Mao C, Feng P. Chem Commun. 2014;50:10390–10393. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03946g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chambers MB, Wang X, Elgrishi N, Hendon CH, Walsh A, Bonnefoy J, Canivet J, Quadrelli EA, Farrusseng D, Mellot-Draznieks C, Fontecave M. ChemSusChem. 2015;8:603–608. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201403345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fei H, Sampson MD, Lee Y, Kubiak CP, Cohen SM. Inorg Chem. 2015;54:6821–6828. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasalevich MA, Becker R, Ramos-Fernandez EV, Castellanos S, Veber SL, Fedin MV, Kapteijn F, Reek JNH, van der Vlugt JI, Gascon J. Energy Environ Sci. 2015;8:364–375. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendon CH, Tiana D, Walsh A. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2012;14:13120–13132. doi: 10.1039/c2cp41099k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jahan M, Bao Q, Loh KP. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:6707–6713. doi: 10.1021/ja211433h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong Y, Shi H-F, Hao Z, Sun J-L, Lin J-H. Dalton Trans. 2013;42:12252–12259. doi: 10.1039/c3dt50697e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fei H, Pullen S, Wagner A, Ott S, Cohen SM. Chem Commun. 2015;51:66–69. doi: 10.1039/c4cc08218d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin S, Pineda-Galvan Y, Maza WA, Epley CC, Zhu J, Kessinger MC, Pushkar Y, Morris AJ. ChemSusChem. 2016 doi: 10.1002/cssc.201601181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson BA, Bhunia A, Ott S. Dalton Trans. 2017 doi: 10.1039/C6DT03718F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hod I, Bury W, Karlin DM, Deria P, Kung C-W, Katz MJ, So M, Klahr B, Jin D, Chung Y-W, Odom TW, et al. Adv Mater. 2014;26:6295–6300. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hod I, Sampson MD, Deria P, Kubiak CP, Farha OK, Hupp JT. ACS Catal. 2015;5:6302–6309. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kornienko N, Zhao Y, Kley CS, Zhu C, Kim D, Lin S, Chang CJ, Yaghi OM, Yang P. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:14129–14135. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senthilkumar M, Mathiyarasu J, Joseph J, Phani KLN, Yegnaraman V. Mater Chem Phys. 2008;108:403–407. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hafizovic Cavka J, Jakobsen S, Olsbye U, Guillou N, Lamberti C, Bordiga S, Lillerud KP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:13850–13851. doi: 10.1021/ja8057953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L, Sasaki T. Chem Rev. 2014;114:9455–9486. doi: 10.1021/cr400627u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang C, Denno ME, Pyakurel P, Venton BJ. Anal Chim Acta. 2015;887:17–37. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen RJ, Zhang Y, Wang D, Dai H. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3838–3839. doi: 10.1021/ja010172b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goebel G, Lisdat F. Electrochem Commun. 2008;10:1691–1694. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joensson-Niedziolka M, Kaminska A, Opallo M. Electrochim Acta. 2010;55:8744–8750. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahrenholtz SR, Epley CC, Morris AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:2464–2472. doi: 10.1021/ja410684q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bard AJ, Faulkner LR. Electrochemical Methods. 2nd edn. Wiley; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.The relatively large capacitive currents were removed form the total peak currents using the GPES software (see ESI (Figure S10A) for more details). The remaining currents that arise from the Faradiac process (ip) were used for the analysis.

- 41.Kornienko N, Zhao Y, Kley CS, Zhu C, Kim D, Lin S, Chang CJ, Yaghi OM, Yang P. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:14129–14135. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.