Abstract

Human butyrylcholinesterase (HuBChE) is under development for use as a pretreatment antidote against nerve agent toxicity. Animals are used to evaluate the efficacy of HuBChE for protection against organophosphorus nerve agents. Pharmacokinetic studies of HuBChE in minipigs showed a mean residence time of 267 h, similar to the half-life of HuBChE in humans, suggesting a high degree of similarity between BChE from 2 sources. Our aim was to compare the biochemical properties of PoBChE purified from porcine milk to HuBChE purified from human plasma. PoBChE hydrolyzed acetylthiocholine slightly faster than butyrylthiocholine, but was sensitive to BChE-specific inhibitors. PoBChE was 50-fold less sensitive to inhibition by DFP than HuBChE and 5-fold slower to reactivate in the presence of 2-PAM. The amino acid sequence of PoBChE determined by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry was 91% identical to HuBChE. Monoclonal antibodies 11D8, mAb2, and 3E8 (HAH 002) recognized both PoBChE and HuBChE. Assembly of 4 identical subunits into tetramers occurred by noncovalent interaction with polyproline-rich peptides in PoBChE as well as in HuBChE, though the set of polyproline-rich peptides in milk-derived PoBChE was different from the set in plasma-derived HuBChE tetramers. It was concluded that the esterase isolated from porcine milk is PoBChE.

Keywords: butyrylcholinesterase, acetylcholinesterase, porcine, polyproline, tetramer, Hupresin

For Table of Contents Use Only

1. Introduction

Vertebrates have two types of cholinesterase (ChE) - acetylcholinesterase (AChE, E.C.3.1.1.7) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE, E.C.3.1.1.8).1 AChE is present in cholinergic synapses in the brain, in autonomic ganglia in the neuromuscular junction, and in the target tissues of the parasympathetic system; its major function is to terminate neurotransmission.2,3 Human BChE (P06276) on chromosome 3q26 4 and human AChE (P22303) on chromosome 7q225 share 70% sequence similarity and 52% sequence identity. Though BChE is widely distributed in organs and tissues, people with a hereditary absence of BChE have no symptoms, making it difficult to assign a physiological function to BChE.6 BChE is primarily synthesized in the liver and is secreted into the plasma. It has been suggested that BChE in plasma functions as a bioscavenger, thereby protecting AChE from inactivation by naturally occurring toxins. This role of BChE is supported by many studies, which demonstrate that exogenously administered BChE can provide protection from the toxicity of organophosphorus (OP) nerve agents.7,8 The involvement of brain BChE in neurotransmission has been demonstrated.9,10 Each enzyme can be distinguished from the other on the basis of substrate specificity and sensitivity to various inhibitors.11 Although AChE is most efficient at hydrolyzing acetylcholine, BChE exhibits less substrate specificity and efficiently hydrolyzes butyryl-, propionyl-, acetyl-, and benzoyl-choline. The two enzymes also can be distinguished by their sensitivity to inhibition by AChE-specific inhibitors BW284c51 and huperzine A, and BChE-specific inhibitors ethopropazine and iso-OMPA.

BChE purified from human plasma (HuBChE) has been studied extensively due to its therapeutic applications.8 Exogenously administered HuBChE can counteract the toxicity of OP nerve agents and pesticides, detoxify cocaine, and alleviate succinylcholine-induced apnea. Our laboratory has focused on developing HuBChE as a bioscavenger for the prophylaxis of OP nerve agent toxicity in humans. For ethical reasons, the efficacy of HuBChE cannot be investigated in humans. Therefore, the toxicity of OP nerve agents and the efficacy of HuBChE against multiple LD50 doses of OP nerve agents are evaluated in animal models. Results from animal studies are extrapolated to humans. Due to many similarities in anatomy and physiology to humans, pigs including minipigs are used for evaluating toxicity from percutaneous, intramuscular, intravenous, and inhalation exposure to OP nerve agents.12–15 Pigs have also been used to evaluate protection against OP nerve agent toxicity afforded by pretreatment with bioscavengers such as HuBChE.16–18 Pharmacokinetic studies showed that the mean residence time of plasma-derived, tetrameric HuBChE in minipigs was 267 h (data not shown), indicating that HuBChE was not rapidly cleared from the circulation of pigs, but remained in the circulation with a half-life similar to that in humans.19 This suggests a high degree of similarity between human (Hu) and porcine (Po) BChE.

Although the biochemical properties of HuBChE are well-characterized, the properties of PoBChE are largely unknown. A choline ester hydrolyzing enzyme, partially purified from porcine milk 20 and porcine parotid gland 21 was identified as PoBChE based on substrate and inhibitor specificity. In agreement with Augustinsson and Olsson 20 we found that porcine milk was a richer source of BChE than porcine plasma. BChE activity was 1–3 U/mL in milk and 0.2 U/mL in plasma, where Units of activity are μmoles butyrylthiocholine hydrolyzed per min. Therefore milk was chosen as the source of PoBChE for the current studies. PoBChE was purified using high speed centrifugation followed by procainamide affinity and gel permeation chromatography. A side-fraction was purified by Hupresin affinity chromatography. The catalytic and inhibitory properties of PoBChE were compared with those of HuBChE and recombinant human acetylcholinesterase (rHuAChE). The bioscavenging properties were evaluated by comparing inhibition by diisopropyl fluorophosphate (DFP) and the aging and reactivation of DFP-inhibited enzyme. The amino acid sequence of PoBChE and the identity of polyproline-rich peptides embedded in PoBChE tetramers were determined by mass spectrometry analysis. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays identified 3 anti-HuBChE monoclonal antibodies that recognize PoBChE.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials

HuBChE was purified from Cohn fraction IV-4 paste, as described.17 Recombinant human acetylcholinesterase (rHuAChE) expressed in CHO cells and purified using procainamide Sepharose 4B affinity chromatography, was provided by Dr. Nageswararao Chilukuri (Division of Biochemistry, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research). Porcine milk was from Waltz farms (Hagerstown, MD). (7-(O,O-diethyl-phosphinyloxy)-1-methylquinolinium methylsulfate (DEPQ) was provided by Drs. Yacov Ashani and Haim Leader (Israel Institute for Biological Research, Ness-Ziona, Israel). Pyridine-2-aldoxime methiodide (2-PAM) was obtained from the Division of Experimental Therapeutics, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. Bio-Spin® 6 chromatography columns and Biogel A 1.5 m column were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). YMC-Pack Diol-300 column for HPLC was from Waters Corp. (Milford, MA). Procainamide Sepharose 4B was from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Hupresin Sepharose 4B was synthesized by Emilie David at CHEMFORASE, 76130 Mont Saint-Aignan, France. Mouse anti-HuBChE monoclonal antibodies 11D8 (accession KT189147 and KT189148), mAb2 (accession KJ141199 and KJ141200), and B2 18–5 (accession KT189143 and KT189144) are described.22, 23 The commercially available mouse anti-HuBChE monoclonal antibody 3E8 (HAH 002–01) was from BioPorto Diagnostics, Denmark via Antibody Shop. All reagent grade chemicals including acetylthiocholine iodide (ATC), butyrylthiocholine iodide (BTC), 5,5-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), 1,5-bis(4-allyldimethylammoniumphenyl)pentan-3 (BW284c51), decamethonium bromide, edrophonium chloride, ethopropazine hydrochloride, tetraisopropyl pyrophosphoramide (iso-OMPA), propidium iodide, tacrine, N-[tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]-3-amino propanesulfonic acid (TAPS), sodium phosphate, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Isolation and Purification of Cholinesterase from Porcine Milk

Porcine milk (1200 mL) was defatted by centrifugation at 5,200 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The purification of BChE from defatted milk was conducted essentially as described.24 Defatted milk was combined with 25 mL of procainamide-Sepharose 4B affinity gel and stirred overnight at 4 °C. The gel was washed with 500 mL of 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, and packed into a 1.5 cm x 20 cm column. Bound PoBChE was eluted with 0.1 M procainamide in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0. Fractions containing BChE activity were pooled and dialyzed against 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0. The enzyme was loaded onto a 1 cm x 20 cm column packed with 10 mL of procainamide-Sepharose 4B gel, washed until the A280 of the effluent was <0.01 and eluted with 0.1 M procainamide in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0. Fractions containing BChE activity were pooled, concentrated in an Amicon stirred cell with a PLGC 30 membrane (Amicon, Beverly, MA) and loaded onto a Biogel A 1.5 m column (1.5 cm x 170 cm) equilibrated in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0. Fractions containing BChE activity were pooled, concentrated using an Amicon PLGC 30 membrane, and stored in 50 % glycerol at −20 °C. Protein concentration was calculated from absorbance at 280 nm where an absorbance of 1.8 corresponded to 1 mg/mL.

A side-fraction of partially purified PoBChE that had been stored in 50% glycerol at −20°C for more than 5 years was purified by affinity chromatography on Hupresin. The PoBChE was dialyzed against 20 mM Tris.HCl pH 7.5 to remove glycerol. A total of 174 units in 13.6 mL were loaded at room temperature onto 16 mL of Hupresin packed in a Pharmacia C16/20 column. Contaminating proteins were washed off with 120 mL of 20 mM Tris.HCl pH 7.5, 0.05% azide followed by 90 mL of 0.3 M NaCl in 20 mM Tris.HCl pH 7.5, 0.05% azide. PoBChE was eluted with 60 mL of 0.1 M tetramethylammonium bromide in 20 mM Tris.HCl pH 7.5, 0.05% azide, with a recovery of 100 units. An additional 40 units were recovered by washing the column with 40 mL of 2 M NaCl in buffer. Proteins were concentrated and desalted in Centricon YM-30 (Millipore/Amicon cat no 4209) centrifugal filters. A portion of the Hupresin-purified PoBChE was used for SDS gel electrophoresis. Another portion was used for LC-MS/MS to identify polyproline-rich peptides and to determine the amino acid sequence of PoBChE.

2.3. Measurement of Cholinesterase Activity

AChE or BChE hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine (ATC), propionylthiocholine (PTC), or butyrylthiocholine (BTC) was measured in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, at 22 °C in the presence of 1.0 mM 5, 5’-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), as described.25 To determine the catalytic parameters for AChE or BChE, initial velocity was measured as a function of ATC, BTC, or PTC over a concentration range of 0.01 – 28 mM, using a microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Units of activity are μmoles per min.

2.4. Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

Hupresin-purified PoBChE was deglycosylated with PNGaseF, reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol, alkylated with 50 mM iodoacetamide, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS on the 6600 Triple-TOF mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA). Details of the protocol have been described.26 Tryptic peptides were searched against the NCBInr 15Sep2014 database for Sus scrofa proteins using the Paragon algorithm from Protein Pilot v5.0.1 (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA). Polyproline-rich peptides were searched using the following parameters: protease none, species Sus scrofa, database NCBInr 15SEP2014.fasta.

The Sus scrofa proteins of interest to this work have been deleted from the NCBInr 2016.5.30 database, but are available in the NCBInr 2013.6.17 and 2015.3.10 databases where the accession numbers for PoBChE are gi335299867 and XP_003358712. Based on our mass spectrometry results, NCBI has assigned accession number NP_001344438.1 to PoBChE in a file dated 04 Nov 2017.

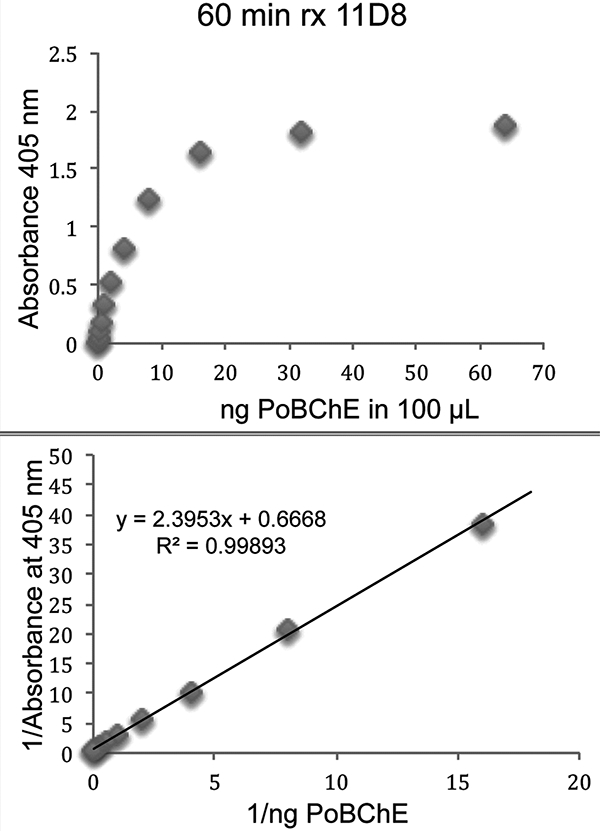

2.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Immulon 4HBX flat bottom 96-well polystyrene plates (Thermo Scientific 3855) were coated with 1 μg of goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma M8642) in 100 μL PBS at 4°C overnight. Wells were blocked with 200 μL of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA)in 20 mM Tris.HCl pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl (Tris-buffered saline, TBS) for 1 h, washed once with TBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST), and incubated with 1 μg/100 μL of anti-human monoclonal antibodies 11D8, mAb2, 3E8, or B2 18–5 for 2 h. Wells were washed 3 times with TBST. PoBChE was diluted with 1 mg/mL BSA in TBS to make 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125, and 0.0625 ng PoBChE/100 μL Each diluted PoBChE solution was added to 8 replicate wells on 4 plates. Control wells were treated with 1 mg/mL BSA in TBS (no PoBChE). Plates were incubated for 1 h, then washed 3 times with TBST. Bound PoBChE was quantified by addition of 100 μL of 1 mM BTC in 0.1 M potassium phosphate pH 7.0 containing 0.5 mM DTNB. The yellow color that developed was recorded at 405 nm in a BioTek plate reader (Winooski, VT).

2.6. Determination of Active-Site Concentration

The concentration of active sites in rHuAChE and PoBChE was determined by titration with 7-(O,O-diethyl-phosphinyloxy)-1-methylquinolinium methylsulfate (DEPQ) as described 27

2.7. Analysis of Catalytic Parameters

The catalytic parameters Km, Kss, and b, were obtained by non-linear, least squares fitting of the data for the hydrolysis of ATC, BTC, or PTC, to Equation 1 28, using GraphPad Prism (v3.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA):

| Equation 1 |

where, v is the initial velocity, Vmax is the maximal velocity, [S] is the concentration of substrate, Km is the Michaelis-Menten constant, Kss is the dissociation constant for excess substrate activation/inhibition, and b reflects the efficiency of hydrolysis by the ternary enzyme substrate complex. When b = 1, the enzyme follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics, whereas substrate inhibition (as in AChE) is indicated when b < 1, and substrate activation (as in BChE) is indicated when b > 1.

2.8. Determination of Inhibition Constants for Non-covalent Inhibitors

The components of competitive and uncompetitive inhibition were determined by measuring the inhibition of enzyme activity in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, over a substrate concentration range of 0.01 – 28 mM and using at least six inhibitor concentrations. Inhibition studies with propidium were carried out in 5 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0. Plots of initial velocities versus substrate concentration at a series of inhibitor concentrations were analyzed using Equation 1 to determine the values of Km and Vmax. Inhibition constants (Ki) for each inhibitor were determined by non-linear least squares fitting of plots of Vmax/Km versus inhibitor concentration using Equation 2 29

| Equation 2 |

2.9. Determination of Dissociation Constants for Propidium

Dissociation constants (KD) for the binding of propidium iodide to rHuAChE, HuBChE, and PoBChE were determined by titrating the fluorescence of propidium using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Titrations were performed in wells of a microtiter plate containing 200 μL of 1.0–2.0 μM enzyme solution in 5 mM Tris.HCl buffer pH 8.0. The fluorescence of the enzyme solution was measured following addition of a small aliquot of propidium, using an excitation wavelength of 520 nm and an emission wavelength of 625 nm. The measured fluorescence was corrected for changes in excitation energy, inner filter effects, and changes in sample volumes during titration by conducting a parallel titration of buffer blank with propidium.30 The KD values of propidium for rHuAChE, HuBChE, and PoBChE were calculated using a Scatchard plot.31 The Scatchard equation is r/[L] = nKa - rKa where L = ligand concentration, n= number of ligand sites, Ka is the association constant, and r = [L]bound/[P]o The symbol r is the ratio of the concentration of bound ligand [L]bound to total available binding sites [P]o A plot of r/[L] versus r yields the Scatchard plot with a slope of -Ka and a Y-intercept of nKa.. The dissociation constant is the inverse of the association constant. To determine if propidium was binding to the active or peripheral anionic site, the active-site of each enzyme was covalently modified by addition of equimolar amounts of paraoxon followed by incubation of the samples at 22 °C for 30 min. These inhibited enzyme samples were used for fluorescence titration as described above.

2.10. pH Dependence of Catalytic Activity

The effect of pH on enzyme activity was determined by measuring activity at various pH values as described.32 substrate concentration range from 0.01 to 28 mM was used with the following buffer solutions: 50 mM sodium acetate at pH 5.0 and 5.5; 50 mM sodium phosphate in the pH range 6.0–8.0; and 50 mM glycine in the pH range 8.0–10.0. The kinetic parameters for the hydrolysis of ATC by rHuAChE and BTC by Po and HuBChE were calculated and the pH dependence of Vmax was fit to a two-pKa model described by Equation 3:

| Equation 3 |

Vmax is the apparent velocity at a given pH and L is Vmax of the reaction. Equation 3 was adapted from 33 Segel p. 892 Enzyme Kinetics, Wiley-Interscience 1975.

2.11. Organophosphorylation of Cholinesterases by DFP

rHuAChE, HuBChE and PoBChE were progressively inhibited with four concentrations of DFP. Excess DFP was added to 0.50 × 10−7 M ChE in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, containing 0.05 % BSA at 25 °C. Aliquots of enzyme-DFP mixtures were withdrawn at various time intervals and assayed for residual activity. The inhibition reaction was pseudo-first order. A plot of the natural log of residual activity versus time gave a straight line. The slope of the line is equal to kobs. A replot of 1/kobs versus 1/[DFP] was linear and yielded ki from the slope of the line. 34 Data were fit to Equation 4 as described.34

| Equation 4 |

where α is defined by Equation 5, and [S] is substrate concentration.

| Equation 5 |

2.12. Reactivation of DFP-Inhibited Cholinesterases by 2-PAM

Second-order rate constants (kr) for the reactivation of ChE-DFP conjugates by 2-PAM were determined as described 35. ChE-DFP conjugates were prepared by incubating enzymes in 0.1 M TAPS buffer, pH 9.0, with a 10-fold molar excess of DFP for 30 min at 22 °C resulting in an inhibition of 95–98% of the starting activity. Excess DFP was removed using Bio-Spin® 6 columns. Aliquots of DFP-inhibited enzyme were diluted with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, containing 0.05% BSA and allowed to reactivate by the addition of 0.01 to 3 mM concentrations of 2-PAM.35,36 Samples were incubated at 25 °C and 10 μL of each mixture was withdrawn at various time intervals and assayed for the recovery of activity. Percent reactivation was determined by comparing reactivated enzyme activity of inhibited sample with uninhibited control sample. A single exponential association equation was used to calculate kobs for each oxime concentration using Equation 6.37

| Equation 6 |

where vt is activity at time t, vo is the starting enzyme activity, kobs is the rate constant of reactivation, and t is time after addition of oxime.37 A replot of kobs versus 2-PAM concentration was used to determine kr. using Equation 7

| Equation 7 |

where kr is the reactivation rate constant and KD is the dissociation constant between 2-PAM and the enzyme.37

2.13. Aging of DFP-Inhibited Cholinesterases

Aging rate constants for DFP-inhibited ChEs were measured as described.38 ChE-DFP conjugates were prepared in 0.1 M TAPS buffer pH 9.0 as described above and aliquots of inhibited enzymes were withdrawn at various time intervals and transferred to tubes containing 10 μL of 1 mM 2-PAM solution. Samples were incubated for 24 h at 22 °C and recovered activity was measured with 1 mM ATC.25 The aging rate constants were determined from Equation 8 for first-order decay:

| Equation 8 |

where ka is the aging rate constant and t is the time at which the inhibition reaction was stopped by 2-PAM.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Isolation of Butyrylcholinesterase from Porcine Milk

Unlike human plasma (4 U/mL), porcine plasma contains very little BChE activity (0.2 U/mL). On the other hand, porcine milk was found to contain 1–3 U/mL of BChE activity. Therefore, milk was used as the source of PoBChE for this study. PoBChE was purified using high speed centrifugation to remove fat, followed by procainamide affinity and gel permeation chromatography. Approximately 3000 U of purified PoBChE with an overall yield of 39% were recovered from 2000 mL of porcine milk. The specific activity of various preparations ranged from 360 to 650 U/mg.

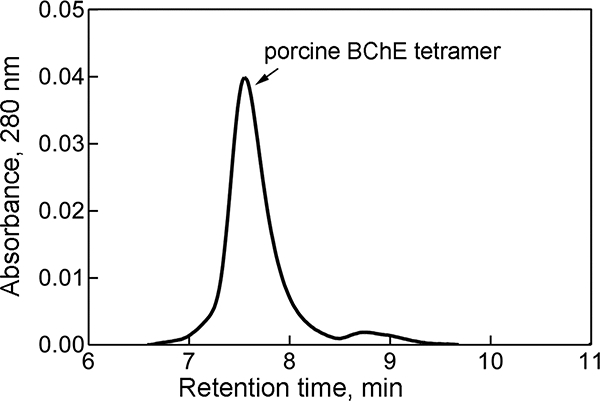

The majority of the enzyme was tetrameric in form. It eluted in a major peak from a YMC-Pack Diol-300 size exclusion column (0.6 cm x 30 cm) with a retention time of 7.51 min (Figure 1), similar to the retention time of tetrameric HuBChE. The small shoulder at 8.8 min had BChE activity and could be a monomer or dimer of BChE.

Figure 1.

Elution profile of PoBChE from a size exclusion YMC-Pack Diol-300 column. Pure PoBChE eluted at 7.5 min, the same time as pure tetrameric HuBChE, indicating that the peak at 7.5 min represents tetrameric PoBChE. The shoulder at 8.8 min had BChE activity.

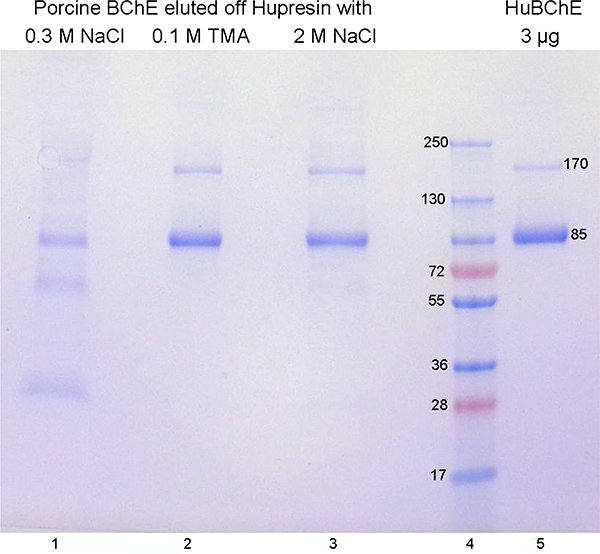

SDS gel electrophoresis of reduced and denatured PoBChE purified by Hupresin affinity chromatography showed a major band at 85 kDa for the PoBChE monomer and a weak band at 170 kDa for the nonreducible PoBChE dimer (Figure 2). A similar pattern of bands was observed for pure HuBChE. These results suggest that the molecular weight of tetrameric PoBChE is similar to the 340,000 Da of the HuBChE tetramer. Sedimentation equilibrium ultracentrifugation of BChE purified from porcine parotid gland yielded a molecular weight of 342,000 to 353,000 Da,21 supporting our conclusion that PoBChE in porcine milk is a tetramer of 340,000 Da.

Figure 2.

SDS gel electrophoresis of Hupresin-purified PoBChE. Contaminating proteins, including some PoBChE, were washed off with 0.3 M NaCl (lane 1). Pure PoBChE was eluted with 0.1 M tetramethylammonium bromide (lane 2) followed by 2 M NaCl (lane 3). Pure HuBChE (lane 5) monomers at 85 kDa and dimers at 170 kDa have the same size as PoBChE.

3.2. Substrate Specificity

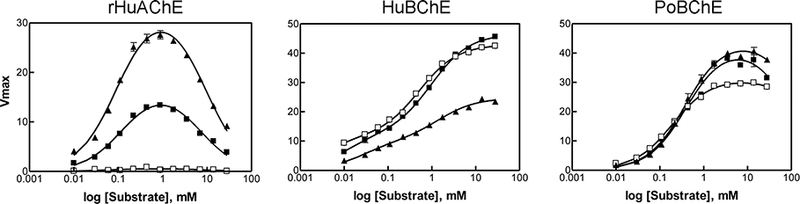

The catalytic parameters of rHuAChE, HuBChE, and PoBChE were determined using three positively-charged substrates, ATC, PTC, and BTC. Activity curves shown in Figure 3 were analyzed by fitting the data to Equation 1 (for rHuAChE and HuBChE) or the Haldane equation (for PoBChE); the catalytic parameters are listed in Table 1. HuBChE showed marked substrate activation with ATC, PTC, and BTC, as indicated by b values of 2.2 to 3.2, while rHuAChE showed substrate inhibition, as indicated by b <1. On the other hand, PoBChE did not show substrate activation, as would be expected for a BChE. Rather a slight inhibition was noted at substrate concentrations >7 mM. In fact, many attempts to fit multiple data sets with PoBChE to Equation 1 failed; therefore catalytic parameters were determined by fitting the data to the Haldane equation. The Haldane equation v = Vmax/ (1 + Km/[S] + [S]/Km) reduces to v = Vmax / (1 + [S]/Kss) when [S]>>Km where S is the substrate concentration. The Km values for PoBChE were almost 10-fold higher than those for HuBChE, for all three positively-charged substrates tested.

Figure 3.

Substrate concentration dependence of activity for rHuAChE, HuBChE and PoBChE: ▲ ATC, ■ PTC, □ BTC.

Table 1.

Steady State Kinetic Constants for rHuAChE, HuBChE and PoBChE

| ChE | Subst rate |

Km, mM | Kss, mM | b | kcat min−1 |

k

cat/K m min−1 mM−1 |

Units/ nmole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rHuAChEa | ATC | 0.11±0.01 | 6.4±1.1 | 0.10±0.01 | 431±35 x103 |

3888±388 x103 |

360 |

| rHuAChEa | PTC | 0.15±0.01 | 4.7±1.6 | 0.11±0.03 | 223±20 x103 |

1512±126 x103 |

|

| rHuAChEa | BTC | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| HuBChEa | ATC | 0.031±0.004 | 1.7±0.3 | 2.23±0.12 | 23±2 x103 |

697±14 ×103 | |

| HuBChEa | PTC | 0.017±0.006 | 1.5±0.4 | 3.26±0.27 | 32±2 x103 |

1510±42 ×103 | |

| HuBChEa | BTC | 0.015±0.003 | 0.7±0.1 | 3.20±0.60 | 30±3 x103 |

1943±178 x103 |

60 |

| PoBChEb | ATC | 0.37±0.06 | 336±167 | ND | 62±3 x103 |

155±9 ×103 | |

| PoBChEb | PTC | 0.25±0.01 | ND | ND | 46±1 x103 |

185±11 ×103 | |

| PoBChEb | BTC | 0.23±0.04 | 287±35 | ND | 43±1 x103 |

172±6 ×103 | 35 |

Catalytic parameters were calculated using equation 1.

Catalytic parameters were calculated using the Haldane equation, therefore b values could not be determined. kcat was calculated as Vmax/[Enzyme]

ND; not determined.

The kcat values for rHuAChE, HuBChE, and PoBChE were determined by normalizing Vmax to the number of active-sites, determined by direct titration with DEPQ, as described 27. Active-site concentrations were determined to be 360 ± 10, 60 ± 6, and 35 ± 2 U/nmol for rHuAChE, HuBChE, and PoBChE, respectively. Consistent with previous reports, kcat values for rHuAChE were 8- to 10- fold higher than those for HuBChE. The kcat value for HuBChE with BTC was 30,000 min−1, which is similar to that reported in the literature 39. Although kcat values for PoBChE were 1.5- to 2- fold higher than those for HuBChE, the higher Km values for PoBChE resulted in much lower kcat/Km values for this enzyme with all three charged substrates tested. Consistent with reported observations,39 the catalytic efficiency of HuBChE measured in terms of kcat/Km, increased with an increase in length of the acyl chain of the substrate (BTC > PTC > ATC). The catalytic efficiency of PoBChE, on the other hand, was not affected by the size of the acyl chain, and all three charged substrates were turned over at similar rates. The catalytic efficiency of rHuAChE decreased with an increase in length of the acyl chain of the substrate.

3.3. pH Dependence of Catalytic Activity

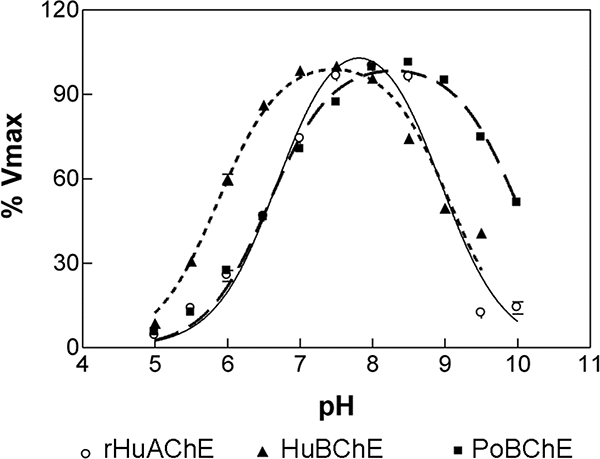

The catalytic activities of rHuAChE, HuBChE, and PoBChE as a function of pH are shown in Figure 4. The bell shaped curves show maximum activity between pH 7.5 and 8.5. The curves were fit to a two pKa mode, Equation 3, yielding calculated pK1 and pK2 values for Hu BChE of 6.65 ± 0.06 and 8.93 ± 0.15, respectively. rHuAChE displayed maximum catalytic activity at pH 8 with calculated pK1 and pK2 values of 6.65 ± 0.06 and 9.99 ± 0.06, respectively. For PoBChE, the maximum catalytic activity was observed between pH 8 to 9 and the calculated pK1 and pK2 values were 5.92 ± 0.01 and 9.10 ± 0.06. The pK value of ~6 is attributed to ionization of His 438 in the catalytic triad. A similar broad pH dependence for porcine BChE activity has been reported 21, with maximum activity in the pH range 7.5 to 9.

Figure 4.

pH dependence of the catalytic activity of rHuAChE, HuBChE and PoBChE. Enzyme activities were determined in various buffers at 25 °C and expressed as a percent of highest activity for each enzyme: ○ rHuAChE; ▲ HuBChE; ■ PoBChE.

3.4. Binding of Inhibitors

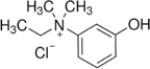

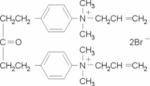

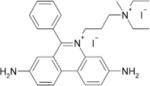

To further understand differences between HuBChE and PoBChE, inhibition studies were conducted with various known inhibitors of AChE and BChE. The Ki values summarized in Table 2 are discussed below. The reversible inhibitors exhibit mixed-type behavior, however only the competitive component is reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Inhibition constants for rHuAChE, HuBChE and PoBChE

| Inhibitor | rHuAChE, Ki (μΜ) |

HuBChE, Ki (μΜ) |

PoBChE, Ki (μΜ) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

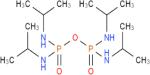

| Ethopropazine |  |

65.3±33.1 | 0.051±0.005 | 0.19±0.01 |

| Iso-OMPA |  |

4.6±0.6 | 0.05±0.01 | 0.06±0.02 |

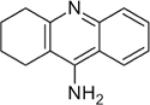

| Tacrine |  |

0.037±0.002 | 0.008±0.002 | 0.00043±0.00007 |

| (−) Huperzine A |  |

0.00032±0.00006 | 75.6 | 28.6±2.2 |

| Edrophonium |  |

0.36±0.01 | 50.4±11.7 | 18.5±2.2 |

| BW284c51 |  |

0.003±0.0001 | 1.9±0.3 | 9.3±0.4 |

| Propidium |  |

0.49±0.10 | 0.40±0.03 | 11.7±3.6 |

| Decamethonium | 2.2±0.1 | 0.8±0.1 | 87.5±15.4 |

Assays were performed in duplicate.

3.5. AChE-Specific Inhibitors

The two AChE-specific inhibitors that were examined were (−) huperzine A and edrophonium 40, 41. As expected for a BChE species, PoBChE displayed a Ki value for (−) huperzine A (28.61 μM) that was much higher than that for rHuAChE, but was similar to the Ki value of 75.6 μM for HuBChE (Table 3). Similarly, inhibition studies with edrophonium, yielded a Ki value of 18.48 μM for PoBChE, which was within 3-fold of that for HuBChE, while being higher than that for rHuAChE. The Ki values of (−) huperzine A and edrophonium for rHuAChE were 20,000-fold and 100-fold lower than those for HuBChE. It was concluded that the enzyme purified from porcine milk is resistant to AChE-specific inhibitors and is therefore classified as BChE.

Table 3.

Inhibition, Aging, and Reactivation rate Constants with DFP

| Enzyme | Inhibition ki, M−1 min−1 | Aging ka, min−1 | Reactivation by 2-PAM kr, M−1 min−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| rHuAChE | 1.33±0.11 × 105 | 129 × 10−5, (t ½ 539 min) | 11.0 |

| HuBChE | 229±10 × 105 | 820 × 10−5, (t ½ 85 min) | 541 ± 23 |

| PoBChE | 5.27±1.03 × 105 | 137 × 10−5, (t ½ 506 min) | 108 ± 4 |

Assays were performed in triplicate.

3.6. BChE-Specific Inhibitors

Three BChE-specific inhibitors, ethopropazine, iso-OMPA, and tacrine were examined. Ethopropazine and tacrine display the most selectivity and the least selectivity for HuBChE, respectively. Inhibition studies with ethopropazine, a substituted phenothiazine, revealed a 1,280-fold difference in Ki between rHuAChE and HuBChE (Table 2). The Ki of ethopropazine for PoBChE was within 4-fold that for HuBChE. An approximately 80 fold higher Ki value was observed for the inhibition of rHuAChE by iso-OMPA compared to HuBChE and PoBChE. Since iso-OMPA is an irreversible inhibitor, the values in Table 2 are apparent Ki.

The Ki value for inhibition of PoBChE by tacrine was approximately an order of magnitude lower (0.43±0.07 nM) than for HuBChE (8±2 nm). It was concluded that the enzyme in porcine milk was inhibited by BChE-specific inhibitors and is therefore classified as BChE.

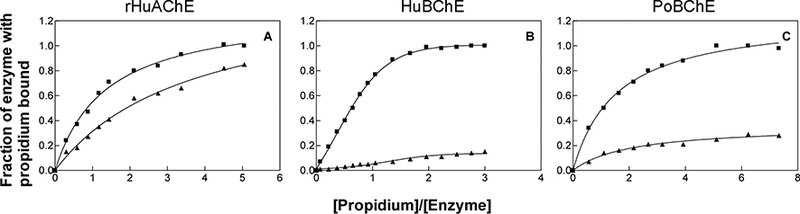

3.7. Bisquaternary Inhibitors

Three bisquaternary inhibitors, propidium, decamethonium, and BW284c51 were examined for binding to rHuAChE, HuBChE and PoBChE. Propidium, a bisquaternary ligand that primarily interacts at the peripheral anionic site of AChE,41 has been reported to bind to the active-site rather than to the peripheral anionic site of BChE.42 Consistent with previous observations,42 inhibition studies with propidium in 5 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, showed that propidium was an uncompetitive inhibitor of rHuAChE and a competitive inhibitor of HuBChE and PoBChE (data not shown). However, propidium displayed a 29-fold lower affinity for PoBChE compared to HuBChE. To further identify the site of interaction of propidium, fluorescence titration studies were conducted with rHuAChE, HuBChE, and PoBChE, and KD values were calculated. Consistent with the observed Ki values, the KD values of propidium for rHuAChE, HuBChE, and PoBChE were determined to be 0.47 ± 0.1, 0.31 ± 0.02, and 1.50 ± 0.23, respectively. As shown in Figure 5, diethoxyphosphorylation of the active site serine with paraoxon significantly reduced the binding of propidium to HuBChE and PoBChE (panels B and C), but had less effect on rHuAChE (panel A). These results confirm previous observations that propidium primarily interacts at the peripheral anionic-site of AChE, but at the active-site of BChE.

Figure 5.

Titration of rHuAChE, HuBChE and PoBChE with propidium using un-modified enzymes (■) as well as with paraoxon-inhibited enzymes (▲).

Unlike propidium, where the quaternary nitrogens are maximally separated by a distance of 4.8 Å, the quaternary nitrogens in decamethonium and BW284c51are maximally separated by 14 Å. Consistent with published observations,43 the Ki of decamethonium for rHuAChE and HuBChE were similar (Table 2). However, decamethonium was 100-fold less potent for PoBChE than for HuBChE. For BW284c51, an AChE-specific inhibitor, a 655-fold difference in Ki was observed between rHuAChE and HuBChE (Table 2). The Ki for PoBChE was within 5-fold of that for HuBChE. It was concluded that the peripheral anionic site in PoBChE has properties similar to the peripheral anionic site in HuBChE.

3.8. Inhibition, Aging, and Reactivation Kinetics with DFP

The bimolecular rate constants for the inhibition of rHuAChE, HuBChE, and PoBChE by DFP and rate constants for aging as well as reactivation of DFP-inhibited enzymes by 2-PAM are shown in Table 3. The inhibition rate constant (ki) for PoBChE of 5.3 × 105 M−1 min−1 was similar to that for rHuAChE, and approximately 50-fold lower than that for HuBChE. This means that HuBChE is more sensitive to inhibition by DFP than rHuAChE, a result consistent with the literature 44, 45. In contrast, PoBChE is 50-fold less sensitive to inhibition by DFP than HuBChE. The aging rate constants ka of DFP-inhibited PoBChE 137 × 10−5 min−1 and rHuAChE 129 × 10−5 min−1 were similar, but 5-fold lower than for HuBChE. The second order rate constants kr for the reactivation of DFP-inhibited HuBChE and PoBChE by 2-PAM, were 10- and 50- fold higher than that for rHuAChE.

3.9. Porcine BChE Amino Acid Sequence

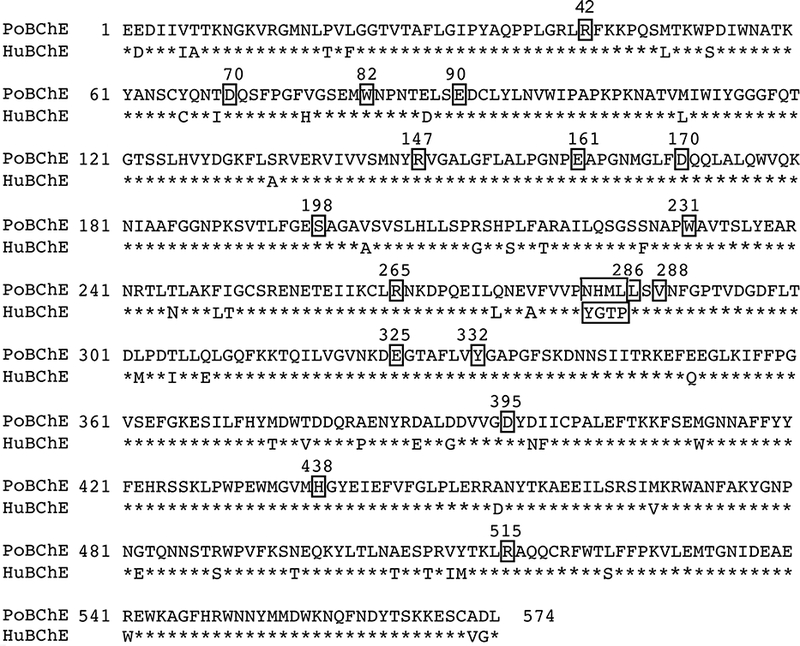

Figure 6 shows the amino acid sequence of milk-derived PoBChE taken from the deleted NCBInr 2015.3.10 database, entry XP_003358712 and 335299867. The 28 amino acid signal peptide has been removed because it is absent in the mature, secreted protein. Mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) confirmed the identity of the sequence in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The amino acid sequence of the protein purified from porcine milk is 91% identical to the amino acid sequence of HuBChE. Mature BChE proteins without the 28 amino acid signal peptide are shown (UniProt accession P06276 for HuBChE and NCBI accession XP_003358712 and 335299867 for PoBChE). Residues were identified by LC-MS/MS of trypsin digested PoBChE. The amino acid sequence of PoBChE has been deposited in the NCBI database under accession number NP_001344438.1. The function of boxed residues is explained in the text.

PoBChE and HuBChE each contain 574 amino acids. Their protein sequences are 91% identical, supporting the conclusion that the esterase in porcine milk is PoBChE.20 Residues known to be important for the function and structure of HuBChE are conserved.46, 47 Residues boxed in Figure 6 include the catalytic triad (S198, E325, H438), the cation-π binding site (W82), the peripheral anionic binding site (D70, Y332), the acyl binding pocket (L286, V288, W231), and salt bridges (R42-E90, R147-D170, R265-E161, R515-D395). Important residues that are not boxed include the oxyanion hole (G116, G117, A199), three intra-chain disulfide bonds (C65-C92, C252-C263, C400-C519), and one interchain disulfide bond (C571-C571). Glycans are attached to 8 asparagines in PoBChE (N57, N106, N241, N256, N341, N455, N481, N486), but to 9 asparagines in HuBChE (N17, N57, N106, N241, N256, N341, N455, N481, N486).48

Computational analysis identified 47 residues that are important for BChE function and structure.49 Four residues in this set are different in PoBChE (V77, V277, L285, I398) compared to HuBChE (H77, A277, P285, F398). H77 makes a hydrogen bond with M81 in the Omega loop. A277 is in the peripheral anionic site at the mouth of the active site gorge. Residues 285 and 398 line the active site gorge.

A patch of 4 residues at 282–285 near the acyl-binding pocket is different in the two enzymes. One positively-charged end of decamethonium interacts with W82 and D197,50 while the main chain faces the acyl-binding pocket of HuBChE. The sequence differences in the 282–285 patch may be responsible for the 100-fold higher Ki value of decamethonium for PoBChE compared to that for HuBChE (Table 2).

3.10. Binding of PoBChE to Anti-HuBChE Antibodies

Four anti-HuBChE monoclonal antibodies were tested for ability to bind PoBChE. It was found that monoclonal antibodies 11D8, mAb2 and 3E8, but not B2 18–5, bound PoBChE. Figure 7 shows ELISA data for monoclonal antibody 11D8. The lowest PoBChE concentration tested, 0.0625 ng in 100 μL (0.0004375 units/mL), had an absorbance at 405 nm of 0.122 after 60 min reaction with BTC/DTNB, which is higher than the 0.096 value for control wells with no PoBChE. PoBChE activity developed fastest with immobilized mAb2 (5-fold faster than with 3E8), slower with 11D8 (2.5-fold faster than with 3E8), and slowest with 3E8, suggesting that 1 μg mAb2 bound 2 times more PoBChE than was bound by 1 μg 11D8, and 5-times more PoBChE than was bound by 1 μg 3E8.

Figure 7.

Binding of PoBChE to immobilized anti-HuBChE monoclonal antibody 11D8 in a 96-well microtiter plate. Antibody-bound PoBChE hydrolyzed butyrylthiocholine, yielding the yellow color detected at 405 nm.

3.11. Polyproline-Rich Peptides in the PoBChE Tetramer

All BChE and AChE tetramers studied to date are composed of 4 identical subunits assembled through non-covalent interaction with a polyproline-rich peptide.26, 51–56 The C-terminal 40 residues of AChE and BChE constitute the tetramerization domain that is required for binding the polyproline-rich peptide. Amino acid analysis of PoBChE purified from porcine parotid gland showed an unusually high proline content of 7.6%,21 suggesting that PoBChE tetramers include a tetramer organizing polyproline-rich peptide. Mass spectrometry analysis of tetrameric PoBChE identified the polyproline-rich peptides listed in Table 4. The polyproline-rich peptides derived from 12 proteins. Two proteins, Zinc finger homeobox protein 4 and Proline-rich Protein 12, each contributed 2 different polyproline-rich peptides. The most abundant polyproline-rich peptide originated from acrosin where the peptide count was 138 and the least abundant from proline-rich protein 16 where the peptide count was 1. The polyproline-rich peptides listed in Table 4 are a composite of the peptides identified by mass spectrometry. For example, the 27 residue peptide in acrosin was deduced from the 25 overlapping peptides listed in Supporting Information Table S1, ranging in length from 11–19 residues. Supporting Information Tables S1-S12 list all the polyproline-rich peptides identified in PoBChE tetramers.

Table 4.

Polyproline-rich peptides in PoBChE tetramers

| Name | Gene | Peptide | Length | MW | Peptide count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrosin | ACR | PAPPPAPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPQQ | 27 | 2648.4 | 138 |

| Homeobox protein HoxB4 | HOXB4 | RDPGPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPGL | 21 | 2069.1 | 116 |

| Lysine-specific demethylase 6B | KDM6B | PLPPPPLPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPLPGLAT | 28 | 2737.5 | 210 |

| Zinc finger homeobox protein 4 | ZFHX4 | TPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPSA | 22 | 2121.1 | 71 |

| Zinc finger homeobox protein 4 | ZFHX4 | TPPPPPPPPPPPPPPSSL | 18 | 1764.9 | 71 |

| Zinc finger CCCH type containing protein 4 | ZC3H4 | GGPPPPPPPPPPPPGPPQM | 19 | 1806.9 | 33 |

| Disabled homolog 2-interacting protein-like isoform 1 | DAB2IP | IDQPPPPPPPPPPAPR | 16 | 1668.9 | 12 |

| Protein FAM171A2 | FAM171A2 | AAAPPPPPPPPPPAPPR | 17 | 1622.9 | 4 |

| FH2 domain-containing protein 1 | FHDC1 | PPPPSPPPPPPPPP | 14 | 1366.7 | 10 |

| Proline-rich protein 12 | PRR12 | APPPPPPPPPPPPPASEPK | 19 | 1863.0 | 123 |

| Proline-rich protein 12 | PRR12 | LPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPP | 20 | 1975.1 | 123 |

| WAS/WASL-interacting protein family member 2 isoform X1 | WIPF2 | MPIPPPPPPPPGPPPPPTF | 19 | 1926.0 | 6 |

| Proline-rich protein 16 | PRR16 | PNPPPPPPR | 9 | 967.5 | 1 |

| Proline-rich membrane anchor 1, partial | PRIMA1 | PPPPLPPPPPPPPPPR | 16 | 1645.9 | 107 |

Peptide count is the total number of polyproline-rich sequences in the LC-MS/MS data set. This number includes peptides that appeared in the data more than once. For example, 25 peptides associated with acrosin appeared 138 times, see Supporting Information Table S1.

MW is the molecular weight of the peptide.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Substrate specificity

PoBChE was isolated from porcine milk and its catalytic and inhibitory properties were compared with rHuAChE and HuBChE. The best substrate for rHuAChE was ATC, and for HuBChE was BTC. However, PoBChE hydrolyzed ATC, BTC, and PTC with similar Km and kcat values. Steady state kinetic studies revealed that the kcat/Km values for PoBChE are 10-fold lower than for HuBChE. This suggests the active site pocket in PoBChE is less efficient at orienting positively charged compounds for hydrolysis compared to HuBChE. The difference in amino acid sequence at positions 282–285 could have a role, since residues 282–285 are part of the lining of the active site gorge and therefore interact directly with substrates. Our substrate specificity studies identified the esterase in porcine milk as ChE, but did not clearly identify it as BChE.

HuBChE displayed substrate activation with all three substrates, whereas PoBChE displayed substrate inhibition at concentrations greater than 7 mM. This result was surprising as it is known that HuBChE shows substrate activation with BTC up to 20 mM, whereas AChE shows substrate inhibition at concentrations of ATC greater than 1 mM,57 Both phenomena are thought to be due to the binding of a substrate molecule at a peripheral anionic site remote from the catalytic site.58, 60 The binding of substrate at the peripheral anionic site allosterically affects conformation at the active-site thus influencing acylation and/or deacylation rates. Using site-directed mutagenesis studies, the residues involved in substrate activation of HuBChE were identified as D70, W82, E197, Y332, and A328.60, 61 All these residues are conserved in PoBChE. It was concluded that the substrate activation results did not prove the esterase in porcine milk is PoBChE.

4.2. Inhibitor specificity

Inhibition studies with BChE-specific inhibitors showed that PoBChE was inhibited by ethopropazine and iso-OMPA with Ki values similar to those for HuBChE. However, AChE-specific inhibitors (−) huperzine A, edrophonium, and BW284c51 were poor inhibitors. This result supported the conclusion that the esterase isolated from porcine milk is PoBChE and is not PoAChE.

PoBChE was more sensitive to inhibition by tacrine compared to HuBChE. PoBChE was less sensitive to propidium and decamethonium compared to HuBChE. The increased affinity of tacrine to PoBChE could be due to differences in amino acid residues in the active-site, in particular at positions 282–285. Previous site-directed mutagenesis studies with AChE mutants showed that the cluster of aromatic amino acid residues, Y72(70), Y124(121), and W286(279), located at the lip of the gorge stabilizes the binding of substrates and inhibitors like BW284C51, decamethonium and propidium.43, 62 Note that the italic numbers in brackets refer to the positions of corresponding residues in the BChE sequence. Although W286(279) is replaced by Ala in HuBChE, consistent with previous observations,43 there was no difference in the inhibition of HuAChE and HuBChE by decamethonium. The orientation of decamethonium in the larger BChE active site gorge is different from that in the AChE gorge.50 Since these residues at the peripheral anionic-site are conserved in PoBChE, the reduced affinity of decamethonium for PoBChE is likely due to differences in the active-site. The relatively larger active-site gorge of HuBChE can accommodate propidium, making it a competitive inhibitor of BChE. Therefore, the reduced affinity of propidium for PoBChE is also due to differences in the active-site.

PoBChE and rHuAChE were relatively insensitive to inhibition by the OP toxicant DFP compared to HuBChE, their rate constants for inhibition being approximately 40- and 150-fold slower than the second order rate constant of 229 ×105 M−1 min−1 for HuBChE. DFP is considered to be a BChE-specific inhibitor since BChE in human plasma is very much more sensitive to inhibition than AChE in human brain and erythrocytes.63, 64 This difference can be seen in other examples. The DFP concentration that inhibits 50% of the horse erythrocyte (AChE) activity in 30 min is 270-fold higher than that for horse plasma enzyme (BChE).45 The inhibitory power, ki, of DFP for HuBChE is 150 times greater than for bovine erythrocyte AChE.44

The rate constant for aging of DFP-inhibited enzyme was similar for PoBChE and rHuAChE, but 7-fold faster for HuBChE. However, the reactivation of DFP-inhibited enzyme by 2-PAM was similar for PoBChE and HuBChE. Overall, our studies with DFP did not provide conclusive proof that the esterase in porcine milk is PoBChE.

4.3. Amino acid sequence and antibody reactivity

Conclusive evidence that the esterase isolated from porcine milk is PoBChE was provided by amino acid sequencing of the purified enzyme. The sequence was 91% identical to that of HuBChE (P06276), 100% identical to that of Sus scrofa BChE (gi335299867 in the deleted NCBInr databases for the years 2013 and 2015), 100% identical to NP_001344438.1 in the November 2017 NCBI database, and only 52% identical to that of PoAChE (gi335284162) in the deleted NCBInr 2013.6.17 and 2015.3.10 databases. Additional support was provided by the observation that anti-HuBChE monoclonal antibodies recognized PoBChE. This result is in agreement with Augustinsson and Olsson that porcine milk contains only one esterase and that the esterase is BChE.20

4.4. Polyproline-rich peptides in PoBChE

Soluble tetramers of human and equine BChE, and of fetal bovine AChE consist of 4 identical subunits plus one polyproline-rich peptide per tetramer.51, 52, 54–56 Membrane-anchored BChE and AChE tetramers are assembled into tetramers through noncovalent interaction with a polyproline-rich region of the proteins COLQ or PRIMA.65, 66 Whereas the membrane-anchored tetramers contain a specific embedded polyproline-rich protein, the soluble tetramers contain peptides from a variety of polyproline-rich proteins. The short polyproline-rich peptides in the soluble tetramers are fragments derived from degradation of proteins that are normally present in the cytoplasm or nuclei of cells. It has been shown that soluble BChE and AChE tetramers can scavenge whatever polyproline-rich peptide is available and incorporate that peptide into their structure.26, 67–70 This view of the identity and origin of polyproline-rich peptides in BChE tetramers is supported by our results for PoBChE tetramers.

PoBChE tetramers contained 14 different polyproline-rich peptides that originated from 12 different proteins. The set of polyproline-rich peptides in PoBChE purified from porcine milk was different from the set of polyproline-rich peptides in HuBChE 55, 56 and equine BChE purified from plasma.52 It was also different from the set of polyproline-rich peptides in recombinant HuBChE tetramers expressed in Chinese Hamster Ovary cells.26 We interpret this to mean that the amino acid sequence of the polyproline-rich peptides present in soluble tetramers depends on the tissue that synthesizes the BChE or AChE. Porcine milk proteins are synthesized in the mammary glands in breast, whereas plasma proteins are synthesized in the liver. This leads to the expectation that the protein donors of the polyproline-rich peptides in milk-derived PoBChE are synthesized in breast tissue. The GTEx portal website (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/gene) shows that every protein in Table 4 is expressed in human breast tissue and by implication in porcine breast.

BChE is known as a bioscavenger of nerve agents and organophosphorus pesticides. Our results are consistent with a second bioscavenger role of BChE in scavenging polyproline-rich peptides released from nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins during cell degradation. Whereas scavenging of toxicants results in loss of BChE activity, scavenging of polyproline-rich peptides stabilizes BChE by assembling the subunits into tetramers.

5. Conclusions

Porcine milk contains BChE and is a richer source of BChE than porcine plasma. The biochemical properties of PoBChE are similar to those of HuBChE, but not identical. The major similarities are 1) PoBChE can be purified by affinity chromatography on procainamide and Hupresin Sepharose, 2) PoBChE is inhibited by BChE-specific inhibitors, 3) PoBChE hydrolyzes ATC, BTC, and PTC, 4) the peripheral anionic site in PoBChE has properties similar to the peripheral anionic site in HuBChE, 5) the amino acid sequence of PoBChE is 91% identical to that of HuBChE, 6) 3 anti-HuBChE monoclonal antibodies recognize PoBChE, 7) PoBChE is a tetramer of 4 identical subunits assembled through noncovalent interaction with a polyproline-rich peptide, 8) the molecular weight of the PoBChE tetramer is 340 kDa.

PoBChE differs from HuBChE as follows: 1) PoBChE does not prefer BTC over ATC and PTC, 2) there is not a clear substrate activation phase for PoBChE, 3) unlike HuBChE, PoBChE is not supersensitive to inhibition by low concentrations of DFP, 4) PoBChE is resistant to inhibition by decamethonium, but supersensitive to inhibition by tacrine.

Supplementary Material

Tables S1-S12 list the amino acid sequences of all the polyproline-rich peptides identified in pure PoBChE tetramers. The supplementary data have been prepared for submission to the Data in Brief journal with the title : Tetramer organizing polyproline-rich peptides identified by mass spectrometry after release of the peptides from Hupresin-purified butyrylcholinesterase tetramers isolated from milk of domestic pig (Sus scrofa).

Highlights.

Porcine milk is a richer source of BChE than porcine plasma.

PoBChE is a tetramer assembled through a polyproline-rich peptide.

PoBChE is purified on procainamide Sepharose or Hupresin affinity gel.

PoBChE amino acid sequence is 91% identical to HuBChE.

PoBChE does not prefer butyryl-over acetyl- and propionylthiocholine.

Acknowledgment:

Mass spectrometry data were obtained by the Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Core Facility at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors, and are not to be construed as official, or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense. This work was supported by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency and the Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA036727.

Abbreviations

- AChE

acetylcholinesterase

- ATC

acetylthiocholine iodide CAS 1866–15-5

- BChE

butyrylcholinesterase

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- BTC

butyrylthiocholine iodide CAS 1866–16-6

- BW284c51

1,5-bis(4-allyldimethylammoniumphenyl)pentan-3-one dibromide CAS 402–40-4

- ChE

cholinesterase

- decamethonium bromide

decane-1,10-bis(trimethylammonium bromide) CAS 541–22-0

- DEPQ

7-(O,O-diethyl-phosphinyloxy)-1-methylquinolinium methylsulfate

- DFP

diisopropyl fluorophosphates CAS 55–91-4

- DTNB

5, 5’-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) CAS 69–78-3

- edrophonium chloride

ethyl(m-hydroxyphenyl)dimethylammonium chloride CAS 116–38-1

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- ethopropazine hydrochloride

10-[2-diethylaminopropyl]phenothiazine hydrochloride CAS 1094–08-2

- rHuAChE

recombinant human acetylcholinesterase P22303

- HuBChE

Human butyrylcholinesterase P06276

- iso-OMPA

tetra(monoisopropyl)pyrophosphortetramide CAS 513–00-8

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- OP

organophosphorus toxicant

- 2-PAM

pyridine-2-aldoxime methiodide CAS 94–63-3

- paraoxon ethyl

(O,O-diethyl O-(4-nitrophenyl) phosphate) CAS 311–45-5

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PNGaseF

peptide-N-glycosidase F

- PoBChE

porcine milk butyrylcholinesterase

- propidium iodide

3,8-diamino-5’−3’-(trimethylammonium)propyl-6-phenylphenanthridinium iodide CAS 25535–16-4

- PTC

propionylthiocholine iodide CAS 1866–73-5

- tacrine

9-amino-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroacridine hydrochloride CAS 1684–40-8

- TAPS

N-[tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]-3-amino propanesulfonic acid CAS 29915–38-6

- TBS

tris-buffered saline, 20 mM Tris.HCl pH 7.4 with 0.15 M NaCl

- TBST

tris-buffer saline plus 0.05% Tween-20

Footnotes

Author Contributions

All authors contributed data, prepared figures and tables, and wrote parts of the manuscript. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- (1).Chatonnet A, and Lockridge O (1989) Comparison of butyrylcholinesterase and acetylcholinesterase. The Biochemical journal 260, 625–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Silman I, and Sussman JL (2005) Acetylcholinesterase: ‘classical’ and ‘non-classical’ functions and pharmacology. Current opinion in pharmacology 5, 293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Soreq H, and Seidman S (2001) Acetylcholinesterase--new roles for an old actor. Nat Rev Neurosci 2, 294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Allderdice PW, Gardner HA, Galutira D, Lockridge O, LaDu BN, and McAlpine PJ (1991) The cloned butyrylcholinesterase (BCHE) gene maps to a single chromosome site, 3q26. Genomics 11, 452–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Getman DK, Eubanks JH, Camp S, Evans GA, and Taylor P (1992) The human gene encoding acetylcholinesterase is located on the long arm of chromosome 7. Am J Hum Genet 51, 170–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Hodgkin W, Giblett ER, Levine H, Bauer W, and Motulsky AG (1965) Complete Pseudocholinesterase Deficiency: Genetic and Immunologic Characterization. J Clin Invest 44, 486–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Saxena A, Sun W, Luo C, Myers TM, Koplovitz I, Lenz DE, and Doctor BP (2006) Bioscavenger for protection from toxicity of organophosphorus compounds. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN 30, 145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ashani Y (2000) Prospective of human butyrylcholinesterase as a detoxifying antidote and potential regulator of controlled-release drugs. Drug Development Research 50, 298–308. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hartmann J, Kiewert C, Duysen EG, Lockridge O, Greig NH, and Klein J (2007) Excessive hippocampal acetylcholine levels in acetylcholinesterase-deficient mice are moderated by butyrylcholinesterase activity. J Neurochem 100, 1421–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Duysen EG, Li B, Darvesh S, and Lockridge O (2007) Sensitivity of butyrylcholinesterase knockout mice to (−)-huperzine A and donepezil suggests humans with butyrylcholinesterase deficiency may not tolerate these Alzheimer’s disease drugs and indicates butyrylcholinesterase function in neurotransmission. Toxicology 233, 60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Austin L, and Berry WK (1953) Two selective inhibitors of cholinesterase. The Biochemical journal 54, 695–700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Saxena A, Sun W, Dabisch PA, Hulet SW, Hastings NB, Jakubowski EM, Mioduszewski RJ, and Doctor BP (2011) Pretreatment with human serum butyrylcholinesterase alone prevents cardiac abnormalities, seizures, and death in Gottingen minipigs exposed to sarin vapor. Biochem Pharmacol 82, 1984–1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Reiter G, Muller S, Hill I, Weatherby K, Thiermann H, Worek F, and Mikler J (2015) In vitro and in vivo toxicological studies of V nerve agents: molecular and stereoselective aspects. Toxicol Lett 232, 438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Langston JL, and Myers TM (2016) VX toxicity in the Gottingen minipig. Toxicol Lett 264, 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Dorandeu F, Foquin A, Briot R, Delacour C, Denis J, Alonso A, Froment MT, Renault F, Lallement G, and Masson P (2008) An unexpected plasma cholinesterase activity rebound after challenge with a high dose of the nerve agent VX. Toxicology 248, 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Saxena A, Sun W, Fedorko JM, Koplovitz I, and Doctor BP (2011) Prophylaxis with human serum butyrylcholinesterase protects guinea pigs exposed to multiple lethal doses of soman or VX. Biochem Pharmacol 81, 164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Saxena A, Tipparaju P, Luo C, and Doctor BP (2010) Pilot-scale production of human serum butyrylcholinesterase suitable for use as a bioscavenger against nerve agent toxicity. Process Biochemistry 45, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Saxena A, Hastings NB, Sun W, Dabisch PA, Hulet SW, Jakubowski EM, Mioduszewski RJ, and Doctor BP (2015) Prophylaxis with human serum butyrylcholinesterase protects Gottingen minipigs exposed to a lethal high-dose of sarin vapor. Chem Biol Interact 238, 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ostergaard D, Viby-Mogensen J, Hanel HK, and Skovgaard LT (1988) Half-life of plasma cholinesterase. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 32, 266–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Augustinsson KB, and Olsson B (1959) Esterases in the milk and blood plasma of swine. I. Substrate specificity and electrophoresis studies. The Biochemical journal 71, 477–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Tucci AF, and Seifter S (1969) Preparation and properties of porcine parotid butyrylcholinesterase. The Journal of biological chemistry 244, 841–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Peng H, Brimijoin S, Hrabovska A, Targosova K, Krejci E, Blake TA, Johnson RC, Masson P, and Lockridge O (2015) Comparison of 5 monoclonal antibodies for immunopurification of human butyrylcholinesterase on Dynabeads: Kd values, binding pairs, and amino acid sequences. Chem Biol Interact 240, 336–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Peng H, Brimijoin S, Hrabovska A, Krejci E, Blake TA, Johnson RC, Masson P, and Lockridge O (2016) Monoclonal antibodies to human butyrylcholinesterase reactive with butyrylcholinesterase in animal plasma. Chem Biol Interact 243, 82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).De la Hoz D, Doctor BP, Ralston JS, Rush RS, and Wolfe AD (1986) A simplified procedure for the purification of large quantities of fetal bovine serum acetylcholinesterase. Life Sci 39, 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V Jr., and Feather-Stone RM (1961) A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol 7, 88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Schopfer LM, and Lockridge O (2016) Tetramer-organizing polyproline-rich peptides differ in CHO cell-expressed and plasma-derived human butyrylcholinesterase tetramers. Biochim Biophys Acta 1864, 706–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Gordon MA, Carpenter DE, Barrett HW, and Wilson IB (1978) Determination of the normality of cholinesterase solutions. Anal Biochem 85, 519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Saxena A, Redman AM, Jiang X, Lockridge O, and Doctor BP (1997) Differences in active site gorge dimensions of cholinesterases revealed by binding of inhibitors to human butyrylcholinesterase. Biochemistry 36, 14642–14651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Saxena A, Fedorko JM, Vinayaka CR, Medhekar R, Radic Z, Taylor P, Lockridge O, and Doctor BP (2003) Aromatic amino-acid residues at the active and peripheral anionic sites control the binding of E2020 (Aricept) to cholinesterases. Eur J Biochem 270, 4447–4458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Saxena A, Hur R, and Doctor BP (1998) Allosteric control of acetylcholinesterase activity by monoclonal antibodies. Biochemistry 37, 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Taylor P, and Jacobs NM (1974) Interaction between bisquaternary ammonium ligands and acetylcholinesterase: complex formation studied by fluorescence quenching. Mol Pharmacol 10, 93–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Saxena A, Hur RS, Luo C, and Doctor BP (2003) Natural monomeric form of fetal bovine serum acetylcholinesterase lacks the C-terminal tetramerization domain. Biochemistry 42, 15292–15299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Segel IH (1975) Enzyme Kinetics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 892 [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ordentlich A, Barak D, Kronman C, Ariel N, Segall Y, Velan B, and Shafferman A (1996) The architecture of human acetylcholinesterase active center probed by interactions with selected organophosphate inhibitors. The Journal of biological chemistry 271, 11953–11962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Luo C, Ashani Y, and Doctor BP (1998) Acceleration of oxime-induced reactivation of organophosphate-inhibited fetal bovine serum acetylcholinesterase by monoquaternary and bisquaternary ligands. Mol Pharmacol 53, 718–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Ashani Y, Radic Z, Tsigelny I, Vellom DC, Pickering NA, Quinn DM, Doctor BP, and Taylor P (1995) Amino acid residues controlling reactivation of organophosphonyl conjugates of acetylcholinesterase by mono- and bisquaternary oximes. The Journal of biological chemistry 270, 6370–6380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Worek F, Wille T, Koller M, and Thiermann H (2012) Reactivation kinetics of a series of related bispyridinium oximes with organophosphate-inhibited human acetylcholinesterase--Structure-activity relationships. Biochem Pharmacol 83, 1700–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Masson P, Fortier PL, Albaret C, Froment MT, Bartels CF, and Lockridge O (1997) Aging of di-isopropyl-phosphorylated human butyrylcholinesterase. The Biochemical journal 327 (Pt 2), 601–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Boeck AT, Schopfer LM, and Lockridge O (2002) DNA sequence of butyrylcholinesterase from the rat: expression of the protein and characterization of the properties of rat butyrylcholinesterase. Biochem Pharmacol 63, 2101–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Saxena A, Qian N, Kovach IM, Kozikowski AP, Pang YP, Vellom DC, Radic Z, Quinn D, Taylor P, and Doctor BP (1994) Identification of amino acid residues involved in the binding of Huperzine A to cholinesterases. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society 3, 1770–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Taylor P, and Lappi S (1975) Interaction of fluorescence probes with acetylcholinesterase. The site and specificity of propidium binding. Biochemistry 14, 1989–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Masson P, Froment MT, Bartels CF, and Lockridge O (1996) Asp70 in the peripheral anionic site of human butyrylcholinesterase. Eur J Biochem 235, 36–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Radic Z, Pickering NA, Vellom DC, Camp S, and Taylor P (1993) Three distinct domains in the cholinesterase molecule confer selectivity for acetyl- and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors. Biochemistry 32, 12074–12084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Main AR, and Iverson F (1966) Measurement of the affinity and phosphorylation constants governing irreversible inhibition of cholinesterases by di-isopropyl phosphorofluoridate. The Biochemical journal 100, 525–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Aldridge WN (1953) The differentiation of true and pseudo cholinesterase by organophosphorus compounds. The Biochemical journal 53, 62–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Nicolet Y, Lockridge O, Masson P, Fontecilla-Camps JC, and Nachon F (2003) Crystal structure of human butyrylcholinesterase and of its complexes with substrate and products. J. Biol. Chem 278, 41141–41147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Nachon F, Masson P, Nicolet Y, Lockridge O, and Fontecilla-Camps JC (2003) Comparison of the structures of butyrylcholinesterase and acetylcholinesterase, Martin Dunitz, London. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Lockridge O, Bartels CF, Vaughan TA, Wong CK, Norton SE, and Johnson LL (1987) Complete amino acid sequence of human serum cholinesterase. The Journal of biological chemistry 262, 549–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Brazzolotto X, Igert A, Guillon V, Santoni G, and Nachon F (2017) Bacterial Expression of Human Butyrylcholinesterase as a Tool for Nerve Agent Bioscavengers Development. Molecules 22, 1828–1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Rosenberry TL, Brazzolotto X, Macdonald IR, Wandhammer M, Trovaslet-Leroy M, Darvesh S, and Nachon F (2017) Comparison of the Binding of Reversible Inhibitors to Human Butyrylcholinesterase and Acetylcholinesterase: A Crystallographic, Kinetic and Calorimetric Study. Molecules 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Biberoglu K, Schopfer LM, Saxena A, Tacal O, and Lockridge O (2013) Polyproline tetramer organizing peptides in fetal bovine serum acetylcholinesterase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1834, 745–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Biberoglu K, Schopfer LM, Tacal O, and Lockridge O (2012) The proline-rich tetramerization peptides in equine serum butyrylcholinesterase. The FEBS journal 279, 3844–3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Noureddine H, Schmitt C, Liu W, Garbay C, Massoulie J, and Bon S (2007) Assembly of acetylcholinesterase tetramers by peptidic motifs from the proline-rich membrane anchor, PRiMA: competition between degradation and secretion pathways of heteromeric complexes. The Journal of biological chemistry 282, 3487–3497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Dvir H, Harel M, Bon S, Liu WQ, Vidal M, Garbay C, Sussman JL, Massoulie J, and Silman I (2004) The synaptic acetylcholinesterase tetramer assembles around a polyproline II helix. Embo J 23, 4394–4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Li H, Schopfer LM, Masson P, and Lockridge O (2008) Lamellipodin proline rich peptides associated with native plasma butyrylcholinesterase tetramers. The Biochemical journal 411, 425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Peng H, Schopfer LM, and Lockridge O (2016) Origin of polyproline-rich peptides in human butyrylcholinesterase tetramers. Chem Biol Interact 259, 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Nachmansohn D, and Rothenberg MA (1945) Studies on cholinesterase. On the specificity of the enzyme in nerve tissue. The Journal of biological chemistry 158, 653–666. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Vellom DC, Radic Z, Li Y, Pickering NA, Camp S, and Taylor P (1993) Amino acid residues controlling acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase specificity. Biochemistry 32, 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Radic Z, Reiner E, and Taylor P (1991) Role of the peripheral anionic site on acetylcholinesterase: inhibition by substrates and coumarin derivatives. Mol Pharmacol 39, 98–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Masson P, Legrand P, Bartels CF, Froment MT, Schopfer LM, and Lockridge O (1997) Role of aspartate 70 and tryptophan 82 in binding of succinyldithiocholine to human butyrylcholinesterase. Biochemistry 36, 2266–2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Masson P, Xie W, Froment MT, and Lockridge O (2001) Effects of mutations of active site residues and amino acids interacting with the Omega loop on substrate activation of butyrylcholinesterase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1544, 166–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Shafferman A, Velan B, Ordentlich A, Kronman C, Grosfeld H, Leitner M, Flashner Y, Cohen S, Barak D, and Ariel N (1992) Substrate inhibition of acetylcholinesterase: residues affecting signal transduction from the surface to the catalytic center. EMBO J 11, 3561–3568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Adams DH, and Thompson RH (1948) The selective inhibition of cholinesterases. The Biochemical journal 42, 170–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Hawkins RD, and Mendel B (1947) Selective inhibition of pseudo-cholinesterase by diisopropyl fluorophosphonate. Brit J Pharmacol 2, 173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Perrier AL, Massoulie J, and Krejci E (2002) PRiMA: the membrane anchor of acetylcholinesterase in the brain. Neuron 33, 275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Krejci E, Thomine S, Boschetti N, Legay C, Sketelj J, and Massoulie J (1997) The mammalian gene of acetylcholinesterase-associated collagen. The Journal of biological chemistry 272, 22840–22847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Altamirano CV, and Lockridge O (1999) Association of tetramers of human butyrylcholinesterase is mediated by conserved aromatic residues of the carboxy terminus. Chem Biol Interact 119-120, 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Bon S, Coussen F, and Massoulie J (1997) Quaternary associations of acetylcholinesterase. II. The polyproline attachment domain of the collagen tail. The Journal of biological chemistry 272, 3016–3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Parikh K, Duysen EG, Snow B, Jensen NS, Manne V, Lockridge O, and Chilukuri N (2011) Gene-delivered butyrylcholinesterase is prophylactic against the toxicity of chemical warfare nerve agents and organophosphorus compounds. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 337, 92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Larson MA, Lockridge O, and Hinrichs SH (2014) Polyproline promotes tetramerization of recombinant human butyrylcholinesterase. The Biochemical journal 462, 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1-S12 list the amino acid sequences of all the polyproline-rich peptides identified in pure PoBChE tetramers. The supplementary data have been prepared for submission to the Data in Brief journal with the title : Tetramer organizing polyproline-rich peptides identified by mass spectrometry after release of the peptides from Hupresin-purified butyrylcholinesterase tetramers isolated from milk of domestic pig (Sus scrofa).