Abstract

Purpose

Anxiety is highly prevalent in many populations; however, the burden of anxiety disorders among pregnant women in low-resource settings is not well documented. We investigated the prevalence and predictors of antenatal anxiety disorders among low-income women living with psychosocial adversity.

Methods

Pregnant women were recruited from an urban, primary level clinic in Cape Town, South Africa. The MINI Plus diagnostic interview assessed prevalence of anxiety disorders. Four self-report questionnaires measured psychosocial characteristics. Logistic regression models explored demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, psychosocial risk factors and psychiatric comorbidity as predictors for anxiety disorders.

Results

Among 376 participants, the prevalence of any anxiety disorder was 23%. Although 11% of all women had post-traumatic stress disorder, 18% of the total sample was diagnosed with other anxiety disorders. Multivariable analysis revealed several predictors for anxiety including: a history of mental health problems (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR]: 4.11; 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.03–8.32), MDE diagnosis (AOR: 3.83; CI 1.99–7.31), multi-gravidity (AOR: 2.87; CI: 1.17–7.07), food insecurity (AOR: 2.57; CI: 1.48–4.46), unplanned and unwanted pregnancy (AOR: 2.14; CI: 1.11–4.15), pregnancy loss (AOR: 2.10; CI: 1.19–3.75); and experience of threatening life events (AOR: 1.30; CI: 1.04–1.57). Increased perceived social support appeared to reduce the risk for antenatal anxiety (AOR: 0.95; CI: 0.91–0.99).

Conclusion

A range of antenatal anxiety disorders are prevalent amongst pregnant women living in low-resource settings. Women who experience psychosocial adversity may be exposed to multiple risk factors, which render them vulnerable to developing antenatal anxiety disorders.

Keywords: perinatal mental health, antenatal anxiety disorders, risk factors, pregnancy, low-income setting

Introduction

The prevalence of Common Perinatal Mental Disorders (CPMD) may have been underestimated in low and middle income countries (LMICs); and although there is substantial comorbidity between depression and anxiety disorders, little is known about antenatal anxiety (Goodman et al. 2014; Biaggi et al. 2016). This is especially true in LMICs where most studies that report diagnostic prevalence of CPMD have investigated depression but not anxiety (Fisher et al. 2012).

Global prevalence estimates for antenatal anxiety disorders vary greatly between regions. For studies reporting any anxiety disorder, prevalence rates range between 4% and 39% (Sawyer et al. 2010; Goodman et al. 2014). Rates in LMICs, ranging between 15% and 39% are generally higher than those reported in high income countries (HIC’s) where reported rates range between 4 and 13% (Adewuya et al. 2006; Tesfaye et al. 2010; Fadzil et al. 2013). Prevalences also vary according to study methodology, whether screening or diagnostic instruments were used (Fisher et al. 2012), and whether a specific anxiety disorder was investigated, rather than the overall prevalence of any anxiety disorder (Goodman et al. 2014).

In South Africa, the diagnostic prevalence of perinatal anxiety disorders range between 3% and 30% for PTSD (Spies et al. 2009; Choi et al. 2015), 1.5% for panic disorder, 2.3% for phobia and 0.8% for social phobia (Spies et al. 2009). Much of the existing research is focused on trauma and stressor-related disorders, and may be specific to the South African context, where there is frequent exposure to community and interpersonal violence or gender-based violence and trauma (Dunkle et al. 2004; Myer et al. 2008b; Troeman et al. 2011; Mahenge et al. 2013; Kastello et al. 2015). A history of childhood trauma and abuse (Choi et al. 2015) and exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) (Hartley et al. 2011) significantly increase the vulnerability for antenatal PTSD, especially in contexts where there are numerous stressors such as poverty, community-based violence and HIV (Shisana et al. 2010; Shisana et al. 2014).

Aetiology and outcomes of antenatal anxiety

There may be a high prevalence of either new onset or worsening of existing anxiety disorders during pregnancy (Heron et al. 2004). This may be due to the substantial hormonal, physiological, psychological and social changes that occur during this time. Antenatal anxiety has been associated with a range of adverse perinatal outcomes for women and their offspring including poor pregnancy and birth outcomes as well as compromised physical, psychological and cognitive development from infancy to adulthood (Wadhwa et al. 1993; Bhagwanani et al. 1997; Kurki et al. 2000; Mulder et al. 2002; O’Connor et al. 2002; Andersson et al. 2004; Van Den Bergh et al. 2005; Talge et al. 2007; Hanlon et al. 2009; Nasreen et al. 2010; Misri et al. 2010; Uguz et al. 2013).

Anxiety disorders during the perinatal period are also associated with unhealthy maternal behaviours such as reduced attendance of antenatal care (Murray et al. 2003), substance use in pregnancy (Eaton et al. 2012; Russell et al. 2013; Eaton et al. 2014; Onah et al. 2016), lower pregnancy weight gain (Dayan et al. 2002) as well as delayed initiation of breastfeeding and diminished capacity of women to care for and nourish their infants (Hanlon et al. 2009). Antenatal anxiety is a significant risk factor for perinatal psychiatric morbidity as it is a strong predictor of perinatal depression (Heron et al. 2004; Milgrom et al. 2008; Hirst and Moutier 2010; Coelho et al. 2011). A history of anxiety disorder appears to confer a greater risk for postnatal depression and anxiety than a history of depressive disorder (Matthey et al. 2003).

Risk factors for antenatal anxiety

Few studies have specifically examined the risk factors for antenatal anxiety disorders, with most studies either reporting risk factors for depression or for comorbid depression and anxiety. A systematic review of risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression reported the most significant predictors for anxiety during pregnancy to be: a previous history of mental illness, particularly a history of depression or anxiety; alcohol and substance use; perceived lack of social support; social conflict or IPV; and poor quality of relationship with a partner (Biaggi et al. 2016). In the same review, studies exploring socio-demographic factors such as age, education level, employment status, income and ethnicity, showed equivocal results (Biaggi et al. 2016). But there is consensus that experience of adverse life events can trigger depressive or anxiety symptoms (Faisal-Cury and Rossi Menezes 2007; Hadley et al. 2008; Biaggi et al. 2016). This is documented for exposure to IPV or emotional, physical or sexual abuse, which has been associated with antenatal anxiety, depression and PTSD symptoms (Mahenge et al. 2013; Fonseca-Machado et al. 2015). Regarding obstetric and pregnancy-related risk factors, unintended or unwanted pregnancy, fear of pregnancy and fear of childbirth (tokophobia) were the most pertinent (Biaggi et al. 2016). The roles of gravidity and parity remain unclear, although primigravidity has been associated with depression, but not with anxiety. Lastly, women with current or past pregnancy complications or past delivery complications, and with a history of pregnancy loss, pregnancy termination or still-birth have been found to be more likely to experience antenatal and pregnancy-specific anxiety (Biaggi et al. 2016).

In settings where women live in extreme poverty and experience high rates of societal stress and violence, the risk factors for CPMD may be intricately connected to their psychosocial and socioeconomic circumstances (Sawyer et al. 2010). However little is known about the diagnostic prevalence of and risk factors for antenatal anxiety disorders in these settings (Howard et al. 2014). This paper aims to establish the diagnostic prevalence of antenatal anxiety disorders in a low-income, primary care, urban setting, and to describe the associated demographic, socioeconomic and psychosocial risk factors.

Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted at a community-based clinic in Hanover Park, an impoverished, densely populated, urban community in Cape Town, South Africa. Hanover Park has a population of approximately 35 000 people, who identify predominantly as “coloured”a, however, the community clinic serves a greater area, which includes black South African residents (Statistics South Africa 2013). The majority of residents live in overcrowded public housing units or informal shacks. Hanover Park experiences high levels of community-based violence, mostly perpetrated by organised gangs active in the area (Benjamin 2014). Local crime statistics indicate that there were 74 homicides reported in 2015, which is 6 times higher than that reported in central Cape Town (Crimestatssa.com). High rates of unemployment (69%) and low levels of education (only 19% have completed high school) contribute to the poverty and lack of opportunity experienced by the majority of residents (Benjamin 2014). Alcohol and drug use are rife, as are IPV, physical and sexual abuse (Moultrie 2004).

Participants

Pregnant women were recruited from the Midwife Obstetric Unit (MOU) which provides primary care, nurse-driven antenatal services at the Hanover Park Community Health Centre (CHC). Women were included in the study if they were over 18 years of age, willing to give informed consent and able to communicate in any of the three commonly spoken languages of the area (English, Afrikaans or isiXhosa).

Ethics

The study was approved by the Faculty of Health Sciences human research ethics committee at the University of Cape Town (HREC REF: 131/2009), and by the Western Cape Department of Health Provincial Research Committee (ref: 19/18/RP88/2009).

Procedures

Data were collected by systematically sampling every third woman as they arrived for their first antenatal visit, prior to having their physical examination and routine HIV test, between November 2011 and August 2012. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants following a verbal explanation of the study and procedure. Willing participants were invited to a private consultation room where socio-demographic data were collected.

Measures

Prior to the commencement of the study all measures had been translated and back-translated from English to Afrikaans and isiXhosa. Self-report questionnaires measuring psychosocial risk factors were administered. Perception of social support was assessed using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet et al. 1988). The MSPSS has been used previously in South Africa with diverse populations (Bruwer et al. 2008), and is psychometrically sound with good validity and reliability. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2) was used to assess IPV in the current relationship. The CTS-2 has good cross-cultural reliability and has been used in low-resource settings (Nayak et al. 2010; Shamu et al. 2011; Kastello et al. 2015) and in South Africa (Dawes et al. 2006; Choi et al. 2014). A short form of the U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) measured inadequacy of food each month, frequency of going hungry, and not having money to buy enough food for the individual or their household in the preceding 6 months (Blumberg et al. 1999). The List of Threatening Experiences (LTE) assessed the number of threatening life experiences faced by women in the preceding 6 months (Brugha et al. 1985). It has been used in other low-resource settings, with antenatal populations (Hanlon et al. 2009) and has good concurrent validity when compared to longer scales (Herrman et al. 2005).

Subsequently, a registered mental health counsellor, trained and supervised by a clinical psychologist, administered the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI Plus) (Sheehan et al. 1998). The MINI Plus diagnoses the major axis I psychiatric disorders in DSM-IV-TR. It has been validated for use in South Africa (Kaminer 2001) and validated translations were used for non-English speaking participants in this study (Myer et al. 2008a; Spies et al. 2009).

Referral for mental health concerns

Women who received a diagnosis of severe psychopathology on the MINI Plus or who presented a high risk for suicide were referred to the emergency psychiatric services at the CHC. Women who received a diagnosis of a common mental disorder (CMD) on the MINI Plus were offered on-site follow-up counselling with the counsellor at an arranged appointment time.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp Inc., College Station, TX, USA). Diagnosed anxiety disorders were allocated to DSM-5-defined categories, namely: anxiety disorders (including generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, agoraphobia, specific phobia and panic disorder); trauma-and stressor-related disorders (including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)), and obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)). For some of the analyses, we collapsed these three categories into one category to include all/any anxiety disorder diagnoses. The prevalence of MDE, comorbid MDE/anxiety and alcohol and drug use disorders were described.

The MSPSS, CTS-2 and HFSSM were assessed for internal consistency and scale reliability using the Cronbach’s α (Cronbach 1951). Frequency distributions described socio-demographic, psychosocial and psychiatric variables of interest. Composite socioeconomic status scores were calculated from household ownership of assets including bank accounts and developed into an asset index using a principal component analysis (van Heyningen et al. 2016). The study population was then stratified into four quartiles: least poor, poor, very poor and poorest.

Variables significantly associated with MINI-diagnosed anxiety disorders were identified using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test (Mann-Whitney test) for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Logistic regression was used to model which of these risk factors were significant predictors of antenatal anxiety diagnosis. Unadjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to determine the strength and direction of these associations.. To adjust for the potential impact of confounding variables, adjusted logistic regression models were specified. Variables included in the adjusted model were those with significant associations in the unadjusted analysis as well as those cited in the literature. Multi-collinearity was assessed among independent variables in the adjusted logistic regression models using the variance inflation factor (Chen et al. 2003). A probability value of p≤0.05 was selected as the level of significance. The coefficients from all regression models were reported as OR with a 95% CI.

Results

Demographic, socioeconomic and clinical characteristics of the sample

A total of 376 women (mean age 27 years; SD 5.8) were recruited. Demographic, socioeconomic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Almost half (48%) were in their 2nd trimester of pregnancy and the majority (74%) were multigravida. Although 90% were married or in a stable relationship, only 60% were living with their partner in the same household. While most women had received some high school education, more than half were unemployed. The overall socioeconomic status of the study sample was low, with 43% reporting a personal income below the lower bound poverty lineb, 42% reporting food insecurity and 13% reporting food insufficiency. Almost 30% of women had experienced at least one threatening life event during the past six months, 19% had experienced two and 11% had experienced three such events. The MSPSS (Cronbach's α 0.89), the CTS2 (Cronbach's α 0.85), and the HFSSM (Cronbach's α 0.83) all exhibited good internal consistency and reliability. The LTE (Cronbach’s α 0.51) demonstrated poor internal consistency and reliability.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample, descriptive and univariate analysis of MINI-defined antenatal anxiety disorders with demographic and psychosocial factors.

| N or mean(%) |

Bivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics N = 376 |

No anxiety (%) |

Diagnosis with any anxiety disorder (%) |

p- value |

Crude OR |

95% CI | p- value |

|

| Socio-demographic variables | |||||||

| + Age: 18 – 24 years | 146 (39) | 118 (41) | 28 (33) | 1.00 | (Reference) | ||

| 25 – 29 years | 114 (30) | 88 (30) | 26 (30) | 1.25 | 0.68–2.27 | 0.475 | |

| ≥30 years | 116 (31) | 84 (29) | 32 (37) | 0.282 | 1.61 | 0.89–2.87 | 0.109 |

| + Ethnicity: Black | 133 (35) | 108 (37) | 25 (29) | 1.00 | (Reference) | ||

| Coloured (mixed race) | 224 (60) | 169 (58) | 55 (64) | 1.41 | 0.83–2.39 | 0.208 | |

| White & “other” | 19 (5) | 13 (4) | 6 (7) | 0.340 | 1.99 | 0.69–5.76 | 0.202 |

| + Highest level of education: ≤ grade 10 | 151 (40) | 114 (39) | 37 (43) | 1.00 | (Reference) | ||

| > grade 10 | 225 (60) | 176 (61) | 49 (57) | 0.534 | 0.86 | 0.53–1.39 | 0.538 |

| + Employment status: Unemployed | 208 (55) | 162 (56) | 46 (53) | 1.00 | (Reference) | ||

| Informal/hawker | 17 (5) | 13 (4) | 4 (5) | 1.08 | 0.34–3.48 | 0.893 | |

| Contract | 23 (6) | 20 (7) | 3 (3) | 0.53 | 0.15–1.86 | 0.320 | |

| Part-time | 28 (7) | 17 (6) | 11 (13) | 2.28 | 0.99–5.21 | 0.051 | |

| Full time | 100 (27) | 78 (27) | 22 (26) | 0.256 | 0.99 | 0.56–1.77 | 0.982 |

| + Socioeconomic status: Least poor | 94 (25) | 71 (25) | 23 (27) | 1.00 | (Reference) | ||

| Poor | 94 (25) | 72 (25) | 22 (26) | 0.94 | 0.48–1.84 | 0.846 | |

| Very poor | 96 (26) | 78 (27) | 18 (20) | 0.71 | 0.36–1.43 | 0.339 | |

| Poorest | 91 (24) | 68 (24) | 23 (27) | 0.710 | 1.04 | 0.54–2.03 | 0.899 |

| + Relationship type: Married | 146 (39) | 110 (38) | 36 (42) | 1.00 | (Reference) | ||

| Stable relationship, unmarried | 192 (51) | 149 (52) | 43 (50) | 0.88 | 0.53–1.46 | 0.627 | |

| Casual relationship | 16 (4) | 14 (5) | 2 (2) | 0.44 | 0.09–2.01 | 0.288 | |

| No relationship / single | 22 (6) | 15 (5) | 5 (6) | 0.756 | 1.02 | 0.35–2.99 | 0.844 |

| + Lives with partner: No | 97 (28) | 80 (30) | 17 (21) | 1.00 | (Reference) | ||

| Yes | 209 (60) | 161 (60) | 48 (60) | 1.40 | 0.76–2.59 | 0.280 | |

| Sometimes | 44 (12) | 29 (10) | 15 (19) | 0.096 | 2.43* | 1.08–5.49 | 0.032 |

| Obstetric variables | |||||||

| + Gravidity: Primigravida | 96 (26) | 87 (30) | 9 (10) | 1.00 | (Reference) | ||

| Multigravida | 280 (74) | 203 (70) | 77 (90) | <0.001 | 3.67** | 1.76–7.64 | 0.001 |

| + Parity: Nulliparous | 122 (32) | 102 (35) | 20 (23) | 1.00 | (Reference) | ||

| Primiparous | 128 (34) | 99 (34) | 29 (34) | 1.49 | 0.79–2.81 | 0.214 | |

| Multiparous | 126 (34) | 89 (31) | 37 (43) | 0.053 | 2.12* | 1.15–3.91 | 0.016 |

| + Past experience of miscarriage/abortion/ stillbirth/ death of a child any time after birth | 116 (31) | 75 (26) | 41 (48) | <0.001 | 2.61** | 1.59–4.29 | ≤0.001 |

| + Trimester: First | 90 (24) | 67 (23) | 23 (27) | 1.00 | (Reference) | ||

| Second | 181 (48) | 145 (50) | 36 (42) | 0.72 | 0.39–1.32 | 0.288 | |

| Third | 105 (28) | 78 (27) | 27 (31) | 0.411 | 1.00 | 0.21–0.55 | 0.980 |

| + Unplanned pregnancy | 237 (63) | 185 (64) | 52 (60) | 0.526 | 1.17 | 0.72–1.93 | 0.524 |

| + Not pleased to be pregnant | 81 (22) | 57 (20) | 24 (28) | 0.134 | 1.58 | 0.91–2.75 | 0.104 |

| Psychosocial variables | |||||||

| + Meets criteria for food insecurity | 158 (42) | 107 (37) | 51 (59) | <0.001 | 2.49** | 1.52–4.08 | ≤0.001 |

| + Meets criteria for food insufficiency | 50 (13) | 29 (10) | 21 (24) | 0.001 | 2.91** | 1.56–5.43 | 0.001 |

| ++ Perceived support from significant othermean score (SD) | 24 (4) | 24 (3.9) | 24 (4.1) | 0.227 | 0.97 | 0.91–1.02 | 0.229 |

| ++ Perceived support from familymean score (SD) | 23 (5) | 23 (4.9) | 21 (5.3) | 0.001 | 0.93* | 0.89–0.97 | 0.002 |

| ++ Perceived support from friends mean score (SD) | 20 (7) | 21 (6.5) | 18 (7.3) | <0.001 | 0.94** | 0.91–0.97 | ≤0.001 |

| + Experience of IPV (CTS2) | 62 (16) | 41 (14) | 21 (24) | 0.031 | 1.96* | 1.08–3.55 | 0.026 |

| ++ Experience of threatening life events (Mean score (SD)) | 1.3 (1.4) | 1.1 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.7) | <0.001 | 1.62** | 1.36–1.92 | ≤0.001 |

| + Self reported history of mental health problems | 57 (15) | 25 (9) | 32 (37) | <0.001 | 6.28** | 3.45–11.44 | ≤0.001 |

| + Current MDE diagnosis | 81 (22) | 36 (12) | 45 (52) | <0.001 | 7.74** | 4.47–13.40 | ≤0.001 |

| + Current suicidal ideation and behavior | 69 (18) | 45 (16) | 24 (28) | 0.011 | 2.11* | 1.19–3.72 | 0.010 |

| + Current alcohol abuse (MINI) | 50 (13) | 33 (11) | 17 (20) | 0.049 | 1.92* | 1.01–3.65 | 0.047 |

| + Current substance abuse (MINI) | 23 (6) | 13 (4) | 10 (12) | 0.021 | 2.80* | 1.18–6.64 | 0.019 |

p <0.05 >0.001

p ≤ 0.001

Fisher’s exact test

Wilcoxon rank sum test

Prevalence of anxiety disorders and comorbidity

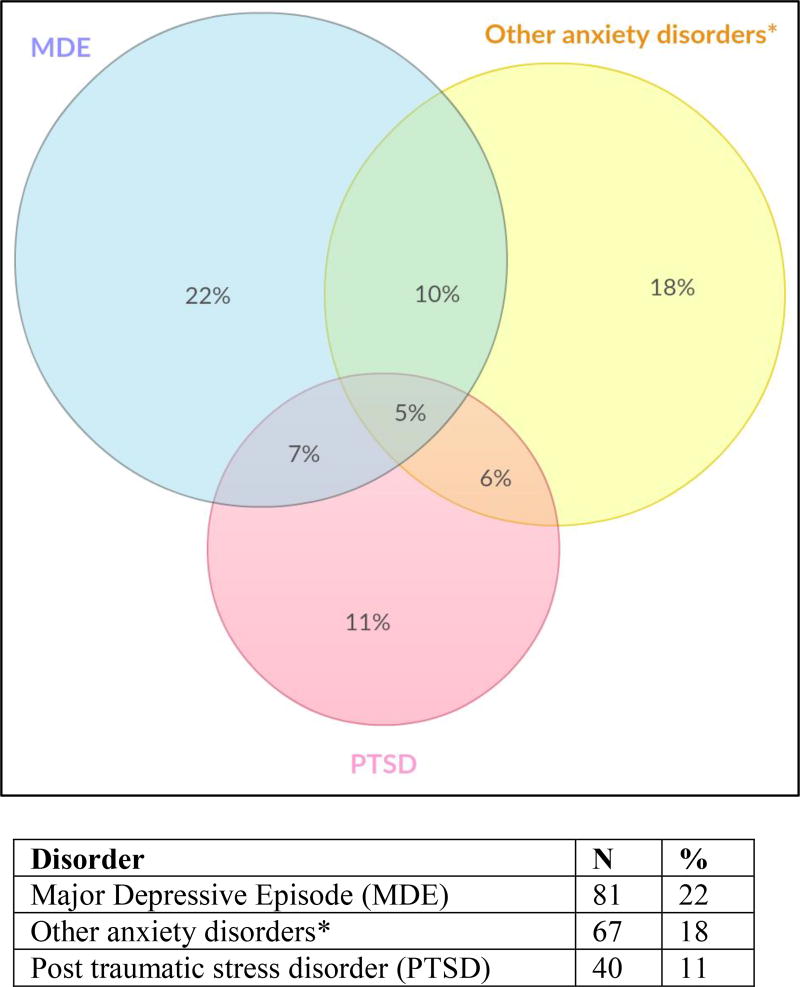

The prevalence of any anxiety disorder was 23%, with 17% of women diagnosed within the group of anxiety disorders that include generalised anxiety disorder (2%), social phobia (7%), agoraphobia (0.3%), specific phobia (6%) and panic disorder (3%); 11% were diagnosed with PTSD and 4% with OCD. The diagnostic prevalence of current MDE was 22%, 18% of women had current suicidal ideation and behaviour (SIB), 13% were using alcohol and 6% were using substances other than alcohol during the current pregnancy. There was a large comorbidity between antenatal anxiety disorders and MDE, with 12% of the total sample having a dual diagnosis. Of those women with a current anxiety diagnosis, 52% also had a diagnosis of current depression (p<0.001). Figure 1 shows the distribution of anxiety diagnoses and the comorbidity with MDE.

Figure 1.

Venn diagram illustrating comorbid diagnoses of MDE, PTSD and other anxiety disorders*

* Includes: generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, agoraphobia, specific phobia and panic disorder

A number of antenatal factors were associated with anxiety diagnosis in the bivariate analysis, including: having increased gravidity, pregnancy and/or child loss; food insecurity and insufficiency; experience of IPV; experience of difficult life events, self-reported history of mental health problems; current MDE diagnosis; current suicidality, and current alcohol or substance abuse (see Table 1). Unadjusted odds ratios showed increased odds for anxiety diagnosis amongst women exposed to these factors, and additionally for those “sometimes” living with their partner. Perceived support from family and friends appeared to decrease the odds for anxiety.

Many of these same factors were also significant in the multivariable models (see Tables 2 and 3). In the model controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors, multigravidity tripled the risk for anxiety diagnosis; unintended and unwanted pregnancies also predicted anxiety as did previous pregnancy loss due to termination, miscarriage or stillbirth or the death of a child at any time. Women that were food insecure were two and a half times more likely to have a diagnosis of anxiety. However, age, socioeconomic status, trimester and whether a woman was living with her partner were not significant predictors. In the model controlling for psychosocial risk variables and comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, the strongest predictor for antenatal anxiety was a previous history of mental health problems, followed by MDE diagnosis. The experience of threatening life events significantly increased the odds of anxiety diagnosis by 1.3 times for every additional stressful event experienced. IPV was not associated with antenatal anxiety, despite it being a known risk factor in the literature. Higher levels of perceived social support from friends decreased the odds for diagnosis with anxiety, although perceived support from family did not. There was no significant predictive value for alcohol and other substance use.

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression model adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics

| Predictors: | AOR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: 18–24 | 1.00 | Reference | |

| 25 – 29 | 0.85 | 0.42–1.77 | 0.677 |

| ≥ 30 | 1.00 | 0.49–2.05 | 0.992 |

| SES: Least poor | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Poor | 1.10 | 0.51–2.36 | 0.805 |

| Very poor | 0.92 | 0.43–2.01 | 0.849 |

| Poorest | 1.48 | 0.69–3.23 | 0.312 |

| Gravidity: primigravida | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Multigravida | 2.87* | 1.17–7.07 | 0.022 |

| Trimester: 1st | 1.00 | Reference | |

| 2nd | 0.60 | 0.31–1.18 | 0.140 |

| 3rd | 0.86 | 0.42–1.81 | 0.705 |

| Living with partner: No | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.14 | 0.57–2.29 | 0.709 |

| Sometimes | 2.29 | 0.95–5.51 | 0.064 |

| Food insecure | 2.57** | 1.48–4.46 | 0.001 |

| Unplanned and unwanted pregnancy1 | 2.14* | 1.11–4.15 | 0.024 |

| Loss of a previous pregnancy or death of a child | 2.10* | 1.19–3.75 | 0.011 |

p <0.05 >0.001

p ≤ 0.001

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression model adjusted for psychosocial risk factors and psychiatric comorbidity

| Predictors: | AOR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived social support from significant other | 1.06 | 0.97–1.15 | 0.188 |

| Perceived social support from family | 0.98 | 0.92–1.04 | 0.441 |

| Perceived social support from friends | 0.95* | 0.91–0.99 | 0.014 |

| Threatening life events | 1.30** | 1.06–1.59 | 0.013 |

| Intimate partner violence | 1.05 | 0.49–2.20 | 0.906 |

| Self reported history of mental health problems | 4.11** | 2.03–8.32 | 0.000 |

| MDE diagnosis (MINI defined) | 3.83** | 1.99–7.31 | 0.000 |

| Current SIB (MINI defined) | 1.97 | 0.99–3.91 | 0.053 |

| Alcohol abuse (MINI defined) | 1.23 | 0.58–2.81 | 0.542 |

| Drug abuse (MINI defined) | 0.88 | 0.29–2.59 | 0.812 |

p <0.05 >0.001

p ≤ 0.001

Discussion

Our study contributes new knowledge about the prevalence and distribution of antenatal anxiety disorders in LMIC settings. Most of the existing literature from LMIC settings has focused on anxiety symptoms (as determined by self-reporting scales), with few data on clinically diagnosed disorders. The results of this study provide new evidence on the high prevalence of antenatal anxiety disorders as well as the distribution of these diagnoses within the anxiety disorder spectrum. Although PTSD accounts for the highest prevalence of a single anxiety disorder, 66% of all anxiety diagnoses are accounted for by disorders from the other anxiety disorder categories. This may be pertinent when developing screening protocols or therapeutic interventions for antenatal anxiety disorders in LMIC settings.

In LMIC settings, there are numerous contextual stressors that render women vulnerable to developing mental health problems (Herba et al. 2016). Experience of adverse or stressful life events is a known predictor of anxiety and depression (Hadley et al. 2008; Biaggi et al. 2016) and results from this study show that for every additional stressful event experienced in the preceding 6 months, the risk for anxiety diagnosis increases by 1.3 times. Considering that a large proportion of participants reported experience of at least one or more of these events, women living in this setting seem to be exposed to high levels of stress, increasing their vulnerability to anxiety. This may also explain the high prevalence of antenatal PTSD in this sample, which is nearly three times higher than in HIC settings (Smith et al. 2004). The high prevalence of antenatal PTSD in this setting, may also be attributable to contextual risk factors, whereby women living in a context with high levels of violence are highly vulnerable to experiencing interpersonal trauma and gender-based violence (Jewkes et al. 2001; Jewkes and Abrahams 2002; Myer et al. 2008b; Gass et al. 2011). PTSD in the perinatal period is strongly associated with obstetric risk, poor birth outcomes (preterm delivery, preeclampsia; poor neonatal health, compromised infant development) and poor maternal-infant attachment (Muzik et al. 2012; Goodman et al. 2014). Given its high prevalence as a single disorder, it may be important to consider when developing mental health interventions for pregnant women living in contexts with elevated rates of violence and interpersonal trauma.

The results of this study confirm that a history of mental health problems and diagnosis with current MDE are strong risk factors for antenatal anxiety. Numerous studies on CPMD have found that a history of mental health disorders increases the risk for current diagnoses and that depression and anxiety are commonly comorbid in the perinatal period (Heron et al. 2004; Littleton et al. 2007; Teixeira et al. 2009; Field et al. 2010; Matthey and Ross-Hamid 2012; Bindt et al. 2012). Where depression and anxiety disorders occur simultaneously, the deleterious effects on maternal and child well-being may be compounded: symptoms may be more severe, duration of episodes of either disorder may be longer and have a chronic course, there may be worse impairment of maternal functioning, a poorer response to treatment and increased suicidality (Field et al. 2010). These findings support the necessity to improve detection of both disorders through screening pregnant women living in LMIC settings, as well as to ask about previous mental health problems.

Women living in this context experience adverse social and economic circumstances, which make them more vulnerable to experiencing food insecurity. Food insecurity has been associated with depression, hazardous drinking, alcohol and other drug use and suicidality amongst pregnant women in South Africa (Dewing et al. 2013; Onah et al. 2016; van Heyningen et al. 2016). Both food insecurity and CPMD have documented negative effects on women’s health and child health and development outcomes (Whitaker et al. 2006; Grote et al. 2010; Ivers and Cullen 2011; Scorgie et al. 2015; Bauer et al. 2016). In this study, food insecurity predicts antenatal anxiety, which is a novel finding in the South African context. It is not clear whether food insecurity predisposes pregnant women to developing anxiety, whether the reverse is true, or whether a bi-directional relationship exists. What is clear, however, is that women living in adverse settings, where there are high rates of unemployment and socioeconomic stressors, seem to be more likely to experience food insecurity, placing them at higher risk of mental health problems (Lund et al. 2010; Sorsdahl et al. 2011; Headey 2013; Muthayya et al. 2013; Doss et al. 2014).

In the presence of stressors such as poverty, food insecurity and adverse life events, perceptions of social support may be a mitigating factor for anxiety diagnosis (Tsai et al. 2012; Reid and Taylor 2015). This is confirmed in our study, which finds perceived support from friends proving to be protective. However, contrary to the literature, perceived support from a significant other or from family was not. Interestingly, Reid and Taylor (2015) found that the source of social support, which mitigated the influence of stressful events, differed for married/cohabiting and for single women(Reid and Taylor 2015). Here, intimate partner support had a greater impact on married/cohabiting women’s mental health than that for single women. However, support from family and friends was protective against depression during the perinatal period for all women, regardless of their relationship status (Reid and Taylor 2015). Support from friends has a greater protective influence on antenatal anxiety than support from intimate partner or family, which may reflect the quality and types of relationships that women have with their partner, family and friends and/or as a result of the stressful environment in which they live (Reid and Taylor 2015). One can hypothesise that where women have discordant, abusive or unstable relationships with their partner and/or family, that their friends may be perceived as more supportive and may act to buffer the stressful influence of conflict in the home.

Study limitations

There were several limitations to the study. Firstly, this was a cross-sectional study and women were only screened once, which limited the tracking of anxiety symptoms across trimesters. Secondly, as this study was clinic-based, women who were unable or unwilling to attend antenatal services, and may be the most vulnerable to mental health problems, were not included in the study. However, the antenatal service uptake rate for the Cape Town Metro area is 83% and thus, our sample is likely to be reasonably reflective of the majority of women in this area (Day and Gray 2013). The urban setting may also affect the generalizability of the results to rural communities. Thirdly, anxiety specific to pregnancy and childbirth, such as tokophobia, was not explored, nor were personality factors associated with anxiety. Fourthly, the cross-sectional design of the study doesn’t supply information on the causal direction of association between anxiety diagnosis and risk factors. Fifthly, the question about loss of a pregnancy or child is a very broad question and does not allow differentiation between antenatal loss, perinatal loss and loss of a child outside of the perinatal period. Asking separate questions about these concepts may have been more useful to explore the impact of previous pregnancy loss or stillbirth as distinct experiences to losing a child after birth. Lastly, the use of self-report measures may have been subject to recall bias and data could not be verified. Use of biological markers such as urine or blood samples to detect current alcohol and other substance use may have provided more accurate data.

Implications

These findings have important implications for those planning perinatal mental health services in low-income settings. Perinatal screening for depression is increasingly common, but we have shown that there is a need also to screen for anxiety to ensure early detection in primary care antenatal services. As the strongest predictors for antenatal anxiety are concurrent MDE and a history of mental health problems, it may be pertinent to screen for anxiety symptoms in conjunction with depression screening and to ask about mental health history.

Mental health services are needed for low-income women, during pregnancy. Where possible, these services should be integrated into existing antenatal services at primary care level (Honikman et al. 2012). There is little evidence from LMIC’s for treatment of non-depressive disorders during pregnancy (Howard et al. 2014) so there is a need for development and testing of such interventions; or to evaluate whether interventions for depression also impact anxiety. A treatment modality that could address either depression and/or anxiety symptoms may be the most practical and cost-effective approach. The Common Elements Treatment Approach (CETA), which has been developed to address mood and/or anxiety problems in LMICs, is one such modality that could be adapted for use within the perinatal period (Murray et al. 2014).

Lastly, in order to address some of the risk factors that are commonly experienced, these services may include targeted interventions, for example counselling for those who have experienced trauma, socio-economic support for women who are food insecure, or psychosocial support for women who have poor support structures (van Heyningen et al. 2016).

In summary, antenatal anxiety is often neglected in studies on perinatal mental health and given low-priority, especially in LMIC settings. The high prevalence of antenatal anxiety disorders presents a serious public health concern as it presents a significant risk factor for maternal morbidity and poor child health and development. These effects may be separate from, and additional to, the effects of perinatal depression, and may be exacerbated by the large comorbidity between the disorders. Furthermore, antenatal anxiety is a strong, well-known predictor for perinatal depression. Therefore, mental health screening of pregnant women should include investigation of anxiety as well as depression.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the women who agreed to participate in our study as well as Sr Loretta Abrahams and the staff of Hanover Park MOU and CHC. We would also like to acknowledge Professor Susan Fawcus who acted as the principal investigator on this project, Bronwyn Evans, Liesl Hermanus and Sheily Ndwayana for their assistance with data collection, and the Western Cape Department of Health for granting us permission to conduct the study at their facility.

This research study was partially funded by the Medical Research Council of South Africa and Cordaid. The PMHP also allocated funds to this study from several donors who had provided general support funding to the organisation, These include: The Douglas G. Murray Trust, the Mary Slack and Daughters Foundation and the Rolf-Stephan Nussbaum Foundation. The Truworths Community Foundation Trust also supported this study. The preparation of the article was funded by the National Research Foundation of South Africa and the Harry Crossley Foundation. MT is a lead investigator with the Centre of Excellence in Human Development, University Witwatersrand, South Africa, and is supported by the National Research Foundation, South Africa. None of the funding sources were involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

In South Africa, the term “coloured” refers to a grouping of people of mixed race ancestry that self-identify as a particular ethnic and cultural grouping.

This was a monthly income of R501 or less, equivalent to approximately 34 US$ per month. According to Statistics South Africa, people earning this amount or less would probably have to sacrifice some food items to be able to afford to buy essential non-food items. Approximately 37% of the South African population live in this income bracket (Statistics South Africa 2015).

The categories for unplanned pregnancy and not pleased to be pregnant were collapsed to create the variable “unplanned and unwanted pregnancy”.

References

- Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Aloba OO, Mapayi BM. Anxiety disorders among Nigerian women in late pregnancy: a controlled study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9:325–8. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson L, Sundström-Poromaa I, Wulff M, et al. Implications of antenatal depression and anxiety for obstetric outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:467–476. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000135277.04565.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A, Knapp M, Parsonage M. Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin A. Community counsellors’ experiences of trauma and resilience in a low-income community. Stellenbosch University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwanani SG, Seagraves K, Dierker LJ, Lax M. Relationship between prenatal anxiety and perinatal outcome in nulliparous women: a prospective study. J Natl Med Assoc. 1997;89:93–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindt C, Appiah-poku J, Bonle MTe, et al. Antepartum Depression and Anxiety Associated with Disability in African Women: Cross-Sectional Results from the CDS Study in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg SJ, Bialostosky K, Hamilton WL, Briefel RR. The effectiveness of a short form of the Household Food Security Scale. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1231–1234. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.8.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugha TS, Bebbington P, Tennant C, Hurry J. The List of Threatening Experiences: a subset of 12 life even categories with considerable long-term contextual threat. Psychol Med. 1985;15:189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer B, Emsley R, Kidd M, et al. Psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in youth. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Ender P, Mitchell M, Wells C. Regression with STATA. UCLA Acad. Technol. Serv; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Choi KW, Abler La, Watt MH, et al. Drinking before and after pregnancy recognition among South African women: the moderating role of traumatic experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KW, Sikkema KJ, Velloza J, et al. Maladaptive coping mediates the influence of childhood trauma on depression and PTSD among pregnant women in South Africa. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18:731–738. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho HF, Murray L, Royal-lawson M, Cooper PJ. Antenatal anxiety disorder as a predictor of postnatal depression?: A longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2011;129:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimestatssa.com. Crime statistics: Phillipi precinct. 2015 [Online]. Available: http://crimestatssa.com.

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Dawes A, de Sas Kropiwnicki Z, Kafaar Z, Richter L. Partner violence. In: Pillay U, Roberts B, Rule S, editors. South African Social Attitudes. HSRC Press; Cape Town, South Africa: 2006. pp. 225–251. [Google Scholar]

- Day C, Gray A. Health and Related Indicators. South African Heal. Rev. 2013:207–329. [Google Scholar]

- Dayan J, Creveuil C, Herlicoviez M, et al. Role of Anxiety and Depression in the Onset of Spontaneous Preterm Labor. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewing S, Tomlinson M, le Roux I, et al. Food insecurity and its association with co-occurring postnatal depression, hazardous drinking, and suicidality among women in peri-urban South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2013:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss C, Summerfield G, Tsikata D. Land, Gender, and Food Security. Fem. Econ. 2014;20:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, et al. Prevalence and patterns of gender-based violence and revictimization among women attending antenatal clinics in Soweto, South Africa. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:230–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Sikkema KJ, et al. Pregnancy, alcohol intake, and intimate partner violence among men and women attending drinking establishments in a Cape Town, South Africa township. J Community Health. 2012;37:208–16. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9438-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, et al. Food Insecurity and Alcohol Use Among Pregnant Women at Alcohol-Serving Establishments in South Africa. Prev Sci. 2014;15:309–317. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0386-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadzil A, Balakrishnan K, Razali R, et al. Risk factors for depression and anxiety among pregnant women in Hospital Tuanku Bainun, Ipoh, Malaysia. Asia-Pacific psychiatry. 2013;5(Suppl 1):7–13. doi: 10.1111/appy.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal-Cury a, Rossi Menezes P. Prevalence of anxiety and depression during pregnancy in a private setting sample. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10:25–32. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, et al. Comorbid depression and anxiety effects on pregnancy and neonatal outcome. Infant Behav Dev. 2010;33:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Mello CDe, Patel V, et al. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:139–149. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.091850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Machado M de O, Monteiro JCDS, Haas VJ, et al. Intimate partner violence and anxiety disorders in pregnancy: the importance of vocational training of the nursing staff in facing them. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2015;23:855–64. doi: 10.1590/0104-1169.0495.2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JD, Stein DJ, Williams DR, Seedat S. Gender differences in risk for intimate partner violence among South African adults. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26:2764–2789. doi: 10.1177/0886260510390960. 0886260510390960 [pii]\r10.1177/0886260510390960 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JH, Chenausky KL, Freeman MP. Anxiety disorders during pregnancy: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:e1153–e1184. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14r09035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, et al. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012–1024. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111.A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley C, Tegegn a, Tessema F, et al. Food insecurity, stressful life events and symptoms of anxiety and depression in east Africa: evidence from the Gilgel Gibe growth and development study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62:980–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.068460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon C, Medhin G, Alem A, et al. Impact of antenatal common mental disorders upon perinatal outcomes in Ethiopia: The P-MaMiE population-based cohort study. Trop Med Int Heal. 2009;14:156–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley M, Tomlinson M, Greco E, et al. Depressed mood in pregnancy: Prevalence and correlates in two Cape Town peri-urban settlements. Reprod Health. 2011;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headey DD. The impact of the global food crisis on self-assessed food security. World Bank Econ Rev. 2013;27:1–27. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhs033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herba CM, Glover V, Ramchandani PG, Rondon MB. Maternal depression and mental health in early childhood: an examination of underlying mechanisms in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:983–992. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J, O’Connor TG, Evans J, et al. The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. J Affect Disord. 2004;80:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrman H, Saxena S, Moodie R, editors. Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice. Geneva: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst KP, Moutier CY. Postpartum major depression. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:926–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honikman S, van Heyningen T, Field S, et al. Stepped care for maternal mental health: A case study of the perinatal mental health project in South Africa. PLoS Med. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis C-L, et al. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet. 2014;384:1775–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivers LC, Cullen Ka. Food insecurity?: special considerations for women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:1740–1744. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.012617.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Abrahams N. The epidemiology of rape and sexual coercion in South Africa: an overview. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Penn-Kekana L, Levin J, et al. Prevalence of emotional, physical and sexual abuse of women in three South African provinces. S Afr Med J. 2001;91:421–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer D. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa: relation to psychiatric status and forgiveness among survivors of human rights abuses. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:373–377. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastello JC, Jacobsen KH, Gaffney KF, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder among low-income women exposed to perinatal intimate partner violence. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurki T, Hiilesmaa V, Raitasalo R, et al. Depression and anxiety in early pregnancy and risk for preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:487–490. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00602-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton HL, Breitkopf CR, Berenson AB. Correlates of anxiety symptoms during pregnancy and association with perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:424–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Breen A, Flisher AJ, et al. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:517–28. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahenge B, Likindikoki S, Stöckl H, Mbwambo J. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and associated mental health symptoms among pregnant women in Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BJOG an Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013:1–8. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthey S, Barnett B, Howie P, Kavanagh DJ. Diagnosing postpartum depression in mothers and fathers: whatever happened to anxiety? J Affect Disord. 2003;74:139–147. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthey S, Ross-Hamid C. Repeat testing on the Edinburgh Depression Scale and the HADS-A in pregnancy: Differentiating between transient and enduring distress. J Affect Disord. 2012:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Bilszta JL, et al. Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: a large prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:147–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misri S, Kendrick K, Oberlander TF, et al. Antenatal depression and anxiety affect postpartum parenting stress: a longitudinal, prospective study. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:222–8. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moultrie A. Indigenous trauma volunteers: survivors with a mission. Rhodes University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder EJH, Robles De Medina PG, Huizink AC, et al. Prenatal maternal stress: Effects on pregnancy and the (unborn) child. Early Hum Dev. 2002;70:3–14. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3782(02)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Woolgar M, Murray J, Cooper P. Self-exclusion from health care in women at high risk for postaprtum depression. J Public Health Med. 2003;25:131–137. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdg028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray LK, Dorsey S, Haroz E, et al. A Common Elements Treatment Approach for Adult Mental Health Problems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Cogn Behav Pr. 2014;21:111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthayya S, Rah JH, Sugimoto JD, et al. The Global Hidden Hunger Indices and Maps? An Advocacy Tool for Action. 2013;8:1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzik M, Bocknek EL, Broderick A, et al. Mother-infant bonding impairment across the first 6 months postpartum: the primacy of psychopathology in women with childhood abuse and neglect histories. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0312-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Smit J, Roux LLe, et al. Common mental disorders among HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scales. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008a;22:147–158. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Stein DJ, Grimsrud A, et al. Social determinants of psychological distress in a nationally-representative sample of South African adults. Soc Sci Med. 2008b;66:1828–40. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreen H-E, Kabir ZN, Forsell Y, Edhborg M. Low birth weight in offspring of women with depressive and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy: Results from a population based study in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak MB, Patel V, Bond JC, Greenfield TK. Partner alcohol use , violence and women ’ s mental health?: population-based survey in India. Br J Psychiatry. 2010:192–199. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.068049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Heron J, Golding J, et al. Maternal antenatal anxiety and children’s behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years. Br J psychiatry. 2002;180:502–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onah MN, Field S, van Heyningen T, Honikman S. Predictors of alcohol and other drug use among pregnant women in a peri-urban South African setting. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10:38. doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0070-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid KM, Taylor MG. Social support, stress, and maternal postpartum depression: A comparison of supportive relationships. Soc Sci Res. 2015;54:246–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell BS, Eaton LA, Petersen-Williams P. Intersecting epidemics among pregnant women: Alcohol use, interpersonal violence, and hiv infection in South Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10:103–110. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0145-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorgie F, Blaauw D, Dooms T, et al. “I get hungry all the time”: experiences of poverty and pregnancy in an urban healthcare setting in South Africa. Global Health. 2015;11:37. doi: 10.1186/s12992-015-0122-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamu S, Abrahams N, Temmerman M, et al. A systematic review of African studies on intimate partner violence against pregnant women: prevalence and risk factors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The Development and Validation of a Structured Diagnostic Psychiatric Interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Rice K, Zungu N, Zuma K. Gender and Poverty in South Africa in the Era of HIV/AIDS: A Quantitative Study. J Women’s Heal. 2010;19:39–46. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MV, Rosenheck RA, Cavaleri MA, et al. Screening for and Detection of Depression, Panic Disorder, and PTSD in Public-Sector Obstetric Clinics. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsdahl K, Slopen N, Siefert K, et al. Household food insufficiency and mental health in South Africa. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:426–31. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.091462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies G, Stein D, Roos A, et al. Validity of the Kessler 10 (K-10) in detecting DSM-IV defined mood and anxiety disorders among pregnant women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:69–74. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. City of Cape Town -- 2011 Census - Ward 047. Cape Town, South Africa: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Methodological report on rebasing of national poverty lines and development on pilot provincial poverty lines: Technical Report. Pretoria: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Talge NM, Neal C, Glover V. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:245–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira C, Figueiredo B, Conde A, et al. Anxiety and depression during pregnancy in women and men. J Affect Disord. 2009;119:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaye M, Hanlon C, Wondimagegn D, Alem A. Detecting postnatal common mental disorders in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and Kessler Scales. J Affect Disord. 2010;122:102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troeman ZC, Spies G, Cherner M, et al. Impact of childhood trauma on functionality and quality of life in HIV-infected women. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:84. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Frongillo EA, et al. Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:2012–2019. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uguz F, Onder E, Sahingoz M, et al. Maternal generalized anxiety disorder during pregnancy and fetal brain development?: A comparative study on cord blood brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels. J Psychosom Res. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Bergh BRH, Mulder EJH, Mennes M, Glover V. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: Links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:237–258. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heyningen T, Myer L, Onah M, et al. Antenatal depression and adversity in urban South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA, Porto M, et al. The association between prenatal stress and infant birth weight and gestational age at birth: A prospective investigation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:858–865. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90016-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker RC, Phillips SM, Orzol SM. Food insecurity and the risks of depression and anxiety in mothers and behavior problems in their preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e859–e868. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]