Abstract

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) and spindle cell melanoma (SCM) are 2 rare subtypes of melanoma. This study aims to investigate these 2 melanomas comprehensively by comparison.

Cases were identified in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database (1973–2017).

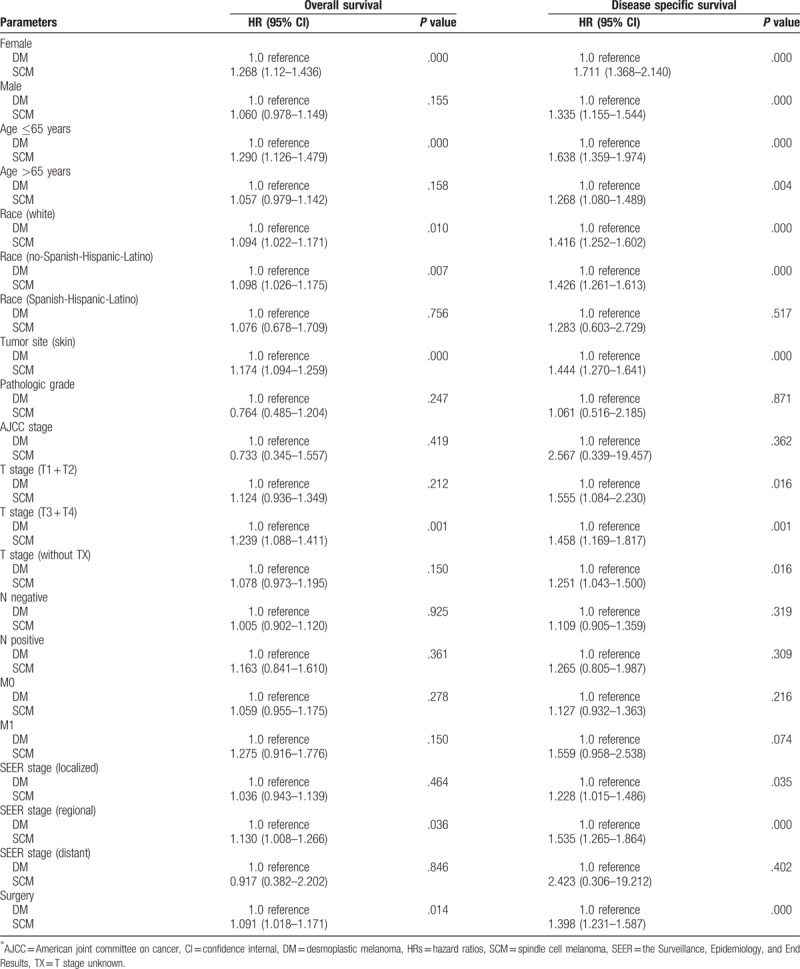

A total of 3657 DM and 4761 SCM cases were identified. DM's female-to-male ratio was 1:2 and SCM's was 0.62:1. The age distribution was similar. Both tumor mostly originated from skin and the eye and orbit was SCM-specific tumor site. Comparing both tumors with DM as reference, significant overall survival (OS) were found depending on sex (women, P < .001), age (age ≤65 years, P < .001), race (white, P = .01), tumor orientation (skin, P < .001), T stage (T3 + T4, P = .001), SEER historic stage (regional tumor, P = .04), and surgery (P = .01). Meanwhile, significant disease specific survival (DSS) differences were found depending on sex (men, P < .001), age (age ≤65 years, P < .001), race (white, P < .001), tumor orientation (skin, P < .001), T early stage (T1 + T2, P = .02), T advanced stage (T3 + T4 stage, P = .001), SEER historic stage (regional tumor, P < .001), and surgery (P < .001). The chance of DSS and OS of SCM were significantly higher comparing to DM for female patients (HR = 1.268, for OS; HR = 1.711, for DSS), patients age ≤65 years (HR = 1.290, for OS; HR = 1.638, for DSS), No-Spanish-Hispanic-Latino patients (HR = 1.098, for OS; HR = 1.426, for DSS), patients with skin tumor (HR = 1.174; for OS; HR = 1.444; for DSS) and patients who received surgery (HR = 1.091; for OS; HR = 1.398, for DSS).

DM and SCM mostly occurred in white people’ skin at 60 to 80 years old and eye and orbit was another most affected site for SCM. SCM had slightly higher occurrence in women and the risk of DSS and OS were significantly higher comparing to DM depending on the women, patients age ≤65 years, patients with skin tumor, No-Spanish-Hispanic-Latino patients and patients who received surgery.

Keywords: desmoplastic melanoma; the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis; spindle cell melanoma

1. Introduction

Desmoplastic melanoma (DM) and spindle cell melanoma (SCM) are rare morphologic variants of melanoma.[1] DM was first described as a variant of SCM in 1971 defining as a melanoma composed of spindle cells and abundant collagen.[2] According to the previous reported statistics, DM's incidence was 2 per million and it accounts for approximately 4% of total melanomas.[3] DM demonstrated a distinctive clinical and histopathologic characteristic. It mostly found in older people over age 60 with sun-damaged skin and affects men more than women.[4] Occurrence of DM is positively associated with excessive sun exposure.[5] DM clinically presented locally aggressive with high recurrence and distant metastasis being less common comparing with nondesmoplastic cutaneous melanoma.[6,7]

Although SCM is one of the variant of melanoma, it may mimic other spindle cell tumors for the lack of conventional melanoma characteristic features and its variable degrees of cytological atypia.[8–10] It was first reported in 1967 and histologically behaved as a pure or mixed spindle neoplastic cells population.[11] SCM (including DM) have an incidence varying form 3% to 14% of total melanomas, and can be found in older people over age 60 and occur anywhere on the body with predominance in men.[9,12–15] Diagnosis of SCM can be challenging and early diagnosis is often delayed.[16] Because it has an aggressive biological behavior and presents typically with widespread metastatic disease, despite the availability of surgical therapy, immunotherapy, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, majority of cases were found at advanced stage and ended up adverse treatment outcome.[8,10,13,17]

DM and SCM are 2 subtypes of malignant melanoma that have similarities and differences in clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic features.[1] Due to the extremely low incidence of DM and SCM, previous studies had substantial limitation of study population and failed to compare the morbidities, clinicopathologic characteristics, treatments, and outcomes between them systematically. To address these questions, we carried out this retrospective study by using the date from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) public-access database collected from various geographic areas in the United States (US) from 1973 to 2017. We hypothesized that incidence and survival outcomes of DM and SCM would be different according to clinico-pathological characteristics.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

To address the research purpose, the investigators designed and implemented a retrospective clinical case series by using data from SEER. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, it was granted an exemption in writing by the University of Fudan institutional review board (IRB). The study population was composed of all patients presenting to for evaluation and management between 1973 and 2017. Briefly, for descriptive analysis of the demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics, inclusion criteria for all available cases were microscopically confirmed, actively followed in patients of known age. For survival analysis, cases were excluded if treatment or outcome data were unavailable. Survival time in months was determined from date of diagnosis to date of death, date last known to be alive, or up to January 2017.

2.2. Variables

Data abstracted from the database for analysis included patient demographic information, such as age at diagnosis, sex, race, and tumor characteristics, such as primary tumor site, histology type, TNM stage, American joint committee on cancer (AJCC) stage, pathological grade (the AJCC grade system), SEER historic stage, treatment modalities, vital status, and follow-up time. SEER historic stage is a simplified version of stage including localized, regional, distant, and unknown stage at diagnosis. Not all of the cases that we identified contained all these data. Cases were excluded if treatment or outcome data were unavailable for survival analysis.

2.3. Data source

The SEER program is comprised of 18 population-based cancer registries around the United States. Records from SEER registries are publicly available and are managed by the National Cancer Institute and it currently represents approximately 30% of the US population.[18] The study populations were identified with International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3), histology codes: 8745/3 for DM and 8772/3 for SCM. Study data were extracted with the official software SEER∗Stat, version 8.3.4 [https://seer.cancer.gov/data/] from the SEER official website.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out by using software of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 23.0, for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Overall statistical analyses were carried out as described previously.[19,20] Briefly, the chi square test or Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables comparison. The survival curves were generated by using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the log-rank test was performed to evaluate the survival difference. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. When the P-value was P < .05, the difference was regarded as statistically significant. All statistical tests were 2 tailed.

3. Results

3.1. Demographical and clinicopathologic characteristics of SCM and DM

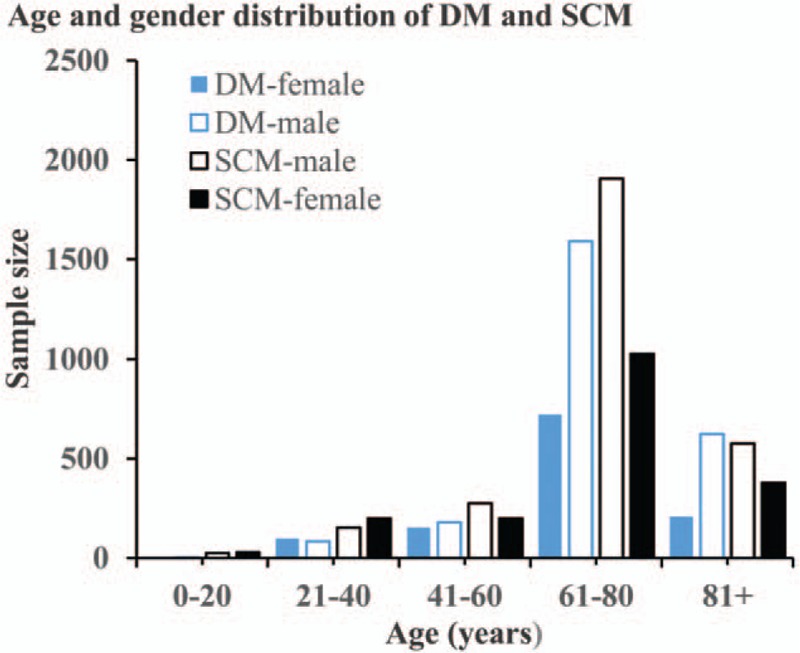

There were 3657 DM and 4761 SCM consecutive registered cases with active follow-up and survival months in the SEER data base from 1973 to 2017. The 3657 DM cases included 1181 women and 2476 men, with a female-to-male ratio of nearly 1:2. Ages of DM cases ranged from 6 years to 101 years and the median age is 68 years. SCM cases consist of 1829 women and 2932 men. The female-to-male ratio is 0.62:1 and the median age is 66 years ranged from 3 years to 101 years. The age and sex distribution were presented in Fig. 1. The median follow-up time was 52 months (range, 0–324 months) for DM and 53 months (range, 0–500 months) for SCM.

Figure 1.

The age and sex distributions of DM and SCM cases. DM = desmoplastic melanoma, SCM = spindle cell melanoma

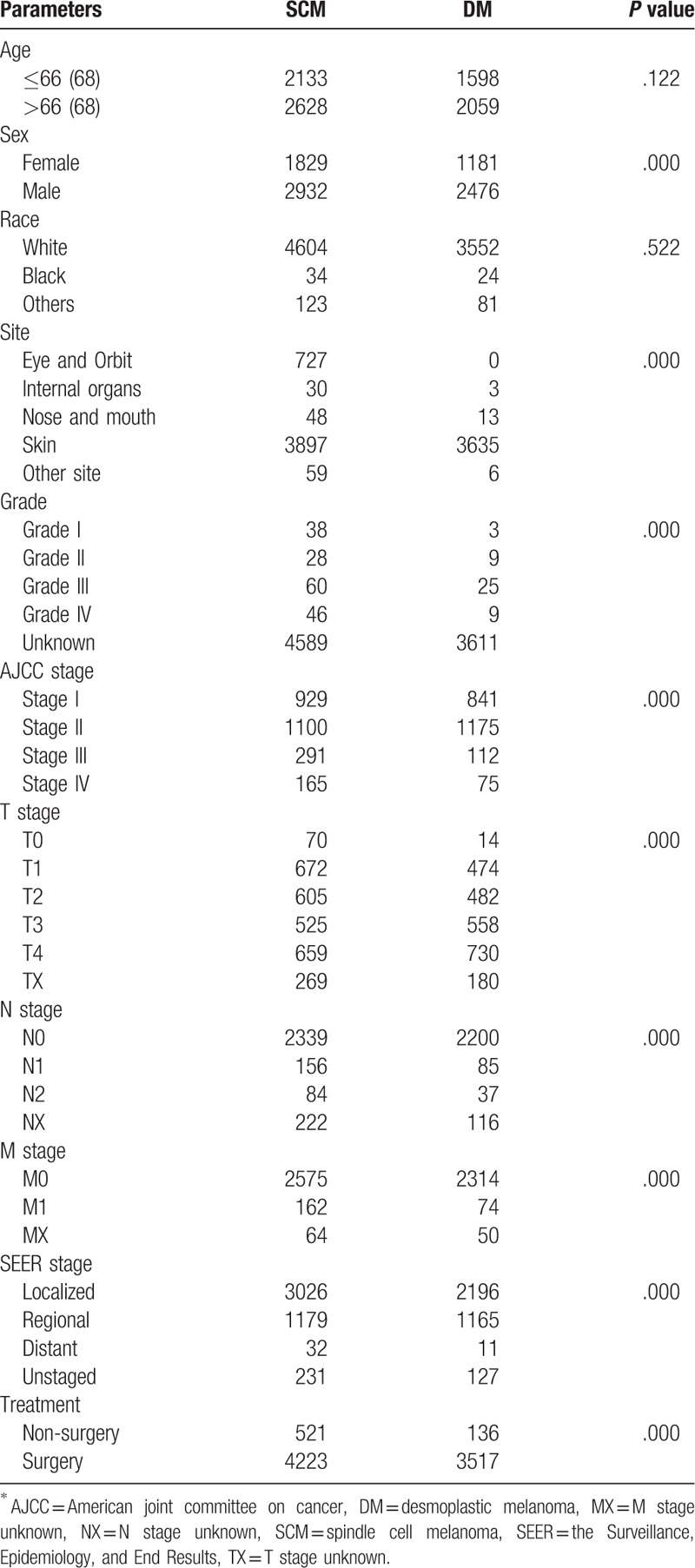

Majority DM and SCM cases occurred in white people and they account for 97.2% (3552/3657) of DM cases and 96.7% (4605/4761) SCM cases. Regarding the tumor origination, skin is most affected site for both tumor and the eye and orbit is the second most affected site for SCM. According to SEER historic stage classification, 63.6% for SCM, 60% for DM, 24.8% for SCM, 31.9% for DM, 0.8% for SCM, 0.3% for DM were classified as localized, regional, and distant metastasized tumor, respectively. For treatment, 96.2% DM cases and 88.7% SCM cases were received surgical treatment. The demographic and clinicopathologic characteristic of DM and SCM cases were summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Epidemiological and clinicopathologic characteristics of SCM and DM∗ cases.

3.2. Survival analysis

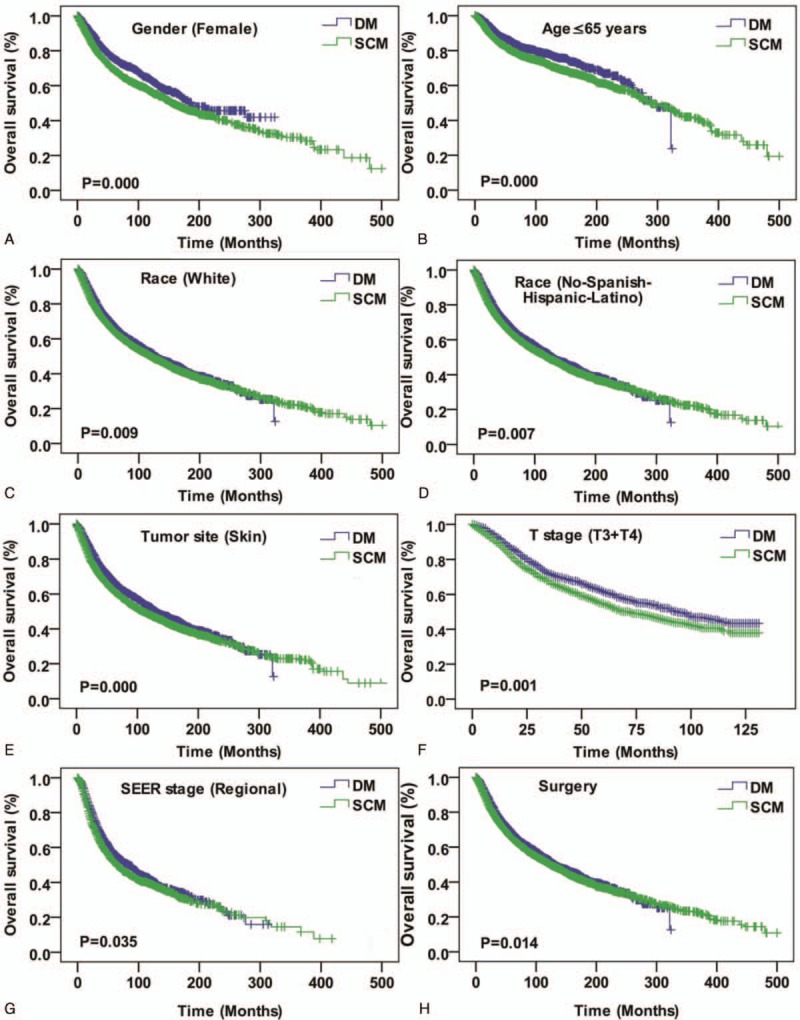

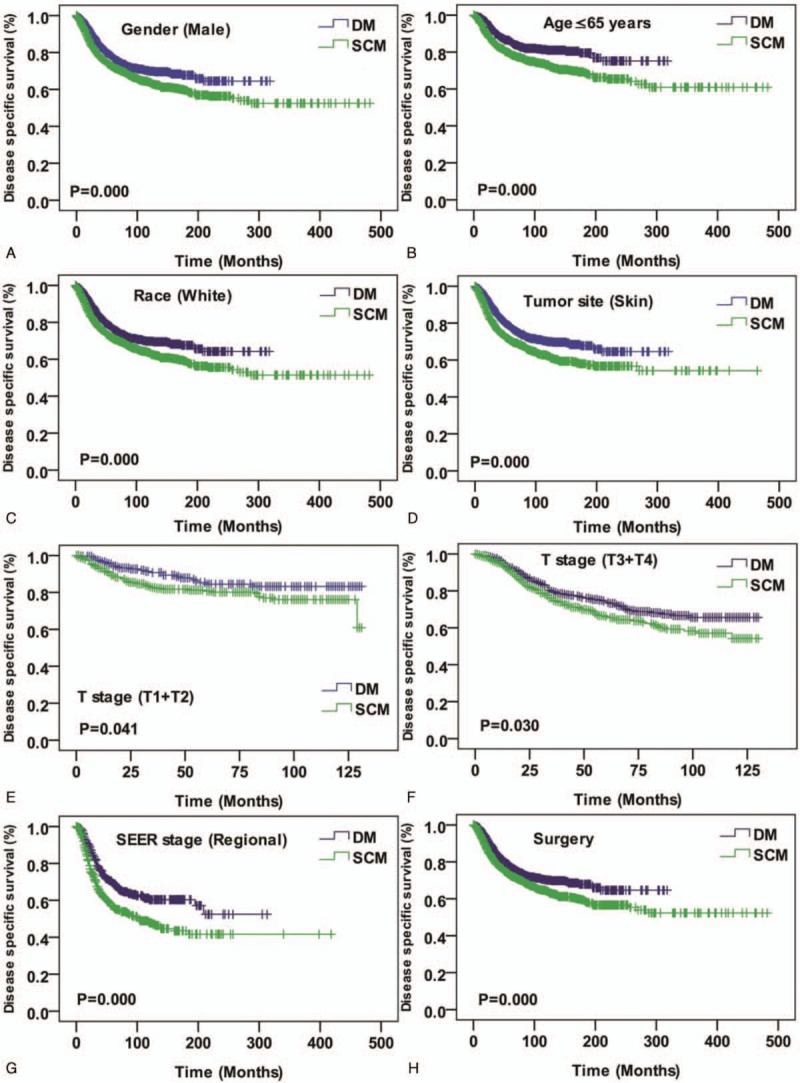

Among 3657 DM and 4761 SCM consecutive registered cases, Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed for time-to-event analysis for overall survival (OS) and disease specific survival (DSS). Comparing overall survival, there were significant survival difference depending on sex (women, P < .001), age (age ≤65 years, P < .001), race (white, P = .01), tumor orientation (skin, P < .001), T stage (T3 + T4, P = .001), SEER historic stage (regional tumor, P = .04) and surgery (P = .01) (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, significant DSS differences were also found depending on sex (men, P < .001), age (age ≤65 years, P < .001), race (white, P = .01), tumor orientation (skin, P < .001), T early stage (T1 + T2, P = .04), T advanced stage (T3 + T4, P = .03), SEER historic stage (regional tumor, P < .001), and surgery (P < .001) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival compared by sex (female) (A), age (age ≤65 years) (B), race (white) (C), race (No-Spanish-Hispanic-Latino) (D), rumor site (skin) (E), T stage (T3 + T4), SEER historic stage (regional tumor) (G), and surgery (H). SEER = the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for disease specific survival compared by sex (male) (A), age (Age ≤65 years) (B), race (white) (C), tumor site (skin) (D), T stage (T1 + T2) (E), T stage (T3 + T4) (F), SEER historic stage (regional tumor) (G), and surgery (H). SEER = the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

We evaluate hazard ratios (HRs) between DM and SCM according to demographical and clinicopathologic characteristics using Cox proportional hazards regression for DSS and OS mortality. The risk of SCM disease specific and overall death were significantly higher comparing to DM for the female patients (HR, 1.268; 95% confidence internal, CI, 1.12–1.436; P < .001, for OS; HR, 1.711; 95% CI, 1.368–2.140; P < .001, for DSS), patients age ≤65 years (HR, 1.290; 95% CI, 1.126–1.479; P < .001, for OS; HR, 1.638; 95% CI, 1.359–1.974; P < .001, for DSS), No-Spanish-Hispanic-Latino patients (HR, 1.098; 95% CI, 1.026–1.175; P = .01, for OS; HR, 1.426; 95% CI, 1.261–1.613; P < .001, for DSS), patients with skin tumor (HR, 1.174; 95% CI, 1.094–1.259; P < .001, for OS; HR, 1.444; 95% CI, 1.270–1.641; P < .001, for DSS) and patients who received surgery (HR, 1.091; 95% CI, 1.018–1.171; P = .01, for OS; HR, 1.398; 95% CI, 1.231–1.587; P < .001, for DSS). Details of these analyses were presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazard models.

4. Discussion

DM and SCM are 2 different rare subtypes of malignant melanoma and have similarities and differences in histologic and clinical features, and reflectance confocal microscopy features and immunohistochemistry are helpful tools for distinguishing them and others.[1,9,21,22] However, few literatures compare them in previous. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first one to attempt to compare morbidity, clinicopathologic characteristic, treatment and outcome systematically in a large sample size.

Regarding sex distribution, men had higher rates of morbidity than women both in DM and SCM and the male-to-female ratio was slightly higher in DM. Both DM and SCM may occur in any age group. However, they mostly concentrated in 60 to 80 years of age group and the median age is 68 years for DM and 66 years SCM, respectively. These results are in accordance with previous study.[4,6,9] Besides, both DM and SCM mostly occurred in white people and there was no significant difference in race distribution.

The eye and orbit was SCM specific tumor site and these cases accounted for 15% of total SCM study cohort. There was no DM cases affected eye and orbit. However, the skin is the most common tumor site for both tumors. According to SEER historic stage classification, localized lesions account for about 60% total cohort for both. Meanwhile, the ratio of DM regional tumor is higher than SCM. This result may be explained by the fact that DM has a characteristic of vertical infiltration characteristic.[23] Previous reports indicated that DM had distant metastasis of >10%.[6,24] In current study, distant metastasis were quite few for both (0.3% for DM, 0.8% for SCM). This inconsistent results are largely may be due to the substantial limitation of the study population.

In survival analysis, DM’ female patients had better OS while the male had better DSS. Regarding other parameters such as age ≤65 years, white people, T advanced stage, skin tumor, SEER historic stage of regional tumor, and patients who received surgery, DM patients demonstrate better prognosis both in OS and DSS. Furthermore, SCM patients may have more survival risks than DM regarding factors such as women, age ≤65 years, No-Spanish-Hispanic-Latino patients, patients with skin tumor, and patients who received surgery. Similarly, previous studies found that survival of DM patients was similar or even better than survival of non-DM patients, and a possible explanation might be that DM has lower incidence of lymphovascular invasion.[25–27] In addition, the vertical infiltration characteristic nature of DM and surgical resection with wide margins can reduce DM recurrence and subsequently improve DM patient's survival.[28]

As a retrospective analysis, a few limitations of this SEER study should be noticed. We could not access the accuracy of diagnosis prior to surgery as the SEER registry is coded based on the final report of pathological examination. Not all cases had complete information and these missing data undoubtedly weaken the strength of current investigation. A number of important prognostic data such as surgical types, margin status, and adjuvant therapies were incomplete in the current available SEER data, and therefore the influence on prognosis could not be assessed. In addition, data on comorbidities that may affect treatment protocols and outcomes is lacking. A notable strength of our study was its robust long-term follow-up assessment of survival provided by SEER comparing to previous reports.

5. Conclusions

Despite these limitations, this study is the first study to compare the 2 uncommon morphologic subtypes of melanoma systematically with largest study population. Investigation results demonstrated that DM and SCM mostly occurred in white people’ skin at 60 to 80 years old. The eye and orbit was a SCM specific tumor site. SCM had a slightly higher occurrence in women and the risk of DSS and OS were significantly higher comparing to DM depending on the females, patients age ≤65 years, patients with skin tumor, No-Spanish-Hispanic-Latino patients, and patients who received surgery.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Kamila Abulimiti (MD) from Strayer University (USA) for checking the English of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Zhe Xu.

Data curation: Feiluore Yibulayin, Ping Shi, Lei Feng.

Investigation: Feiluore Yibulayin, Ping Shi.

Project administration: Lei Feng.

Resources: Lei Feng.

Software: Feiluore Yibulayin, Ping Shi.

Supervision: Lei Feng.

Writing – original draft: Zhe Xu.

Writing – review and editing: Lei Feng, Zhe Xu.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AJCC = American joint committee on cancer, CI = confidence internal, DM = desmoplastic melanoma, DSS = disease specific survival, HRs = hazard ratios, OS = overall survival, SCM = spindle cell melanoma, SEER = the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

ZX and FY have contributed equally to this study.

Ethical approval: For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Funding: Not appliable.

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Weissinger S, Keil P, Silvers D, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol 2014;27:524–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Conley J, Lattes R, Orr W. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma (a rare variant of spindle cell melanoma). Cancer 1971;28:914–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Feng Z, Wu X, Chen V, et al. Incidence and survival of desmoplastic melanoma in the United States, 1992–2007. J Cutan Pathol 2011;38:616–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Manfredini M, Pellacani G, Losi L, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a challenge for the oncologist. Future Oncol 2017;13:337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jain S, Allen PW. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma and its variants. A study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1989;13:358–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pace CS, Kapil JP, Wolfe LG, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: clinical behavior and management implications. Eplasty 2016;16:e3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Maurichi A, Miceli R, Camerini T, et al. Pure desmoplastic melanoma: a melanoma with distinctive clinical behavior. Ann Surg 2010;252:1052–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Piao Y, Guo M, Gong Y. Diagnostic challenges of metastatic spindle cell melanoma on fine-needle aspiration specimens. Cancer 2008;114:94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Walia R, Jain D, Mathur SR, et al. Spindle cell melanoma: a comparison of the cytomorphological features with the epithelioid variant. Acta Cytol 2013;57:557–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dainichi T, Kobayashi C, Fujita S, et al. Interdigital amelanotic spindle-cell melanoma mimicking an inflammatory process due to dermatophytosis. J Dermatol 2007;34:716–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wachtel JG, Caplan CW, Makley TA., Jr Juvenile melanoma (mixed spindle cell and epithelioid cell nevus) of the conjunctiva. Surv Ophthalmol 1967;12:12–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sundersingh S, Majhi U, Narayanaswamy K, et al. Primary spindle cell melanoma of the urinary bladder. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2011;54:422–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Arora SK, Gupta N, Kang M, et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytology in a case of metastatic spindle cell melanoma in liver. Diagn Cytopathol 2010;38:425–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Murali R, Doubrovsky A, Watson GF, et al. Diagnosis of metastatic melanoma by fine-needle biopsy: analysis of 2,204 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 2007;127:385–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gupta SK, Rajwanshi AK, Das DK. Fine needle aspiration cytology smear patterns of malignant melanoma. Acta Cytol 1985;29:983–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Diaz A, Valera A, Carrera C, et al. Pigmented spindle cell nevus: clues for differentiating it from spindle cell malignant melanoma. A comprehensive survey including clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and FISH studies. Am J Surg Pathol 2011;35:1733–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mayayo Artal E, Gomez-Aracil V, Mayayo Alvira R, et al. Spindle cell malignant melanoma metastatic to the breast from a pigmented lesion on the back. A case report. Acta Cytol 2004;48:387–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cronin KA, Ries LA, Edwards BK. The surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (seer) program of the National Cancer Institute. Cancer 2014;120:3755–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wushou A, Jiang YZ, Liu YR, et al. The demographic features, clinicopathologic characteristics, treatment outcome and disease-specific prognostic factors of solitary fibrous tumor: a population-based analysis. Oncotarget 2015;6:41875–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Feng L, Cai D, Muhetaer A, et al. Spindle cell carcinoma: the general demographics, basic clinico-pathologic characteristics, treatment, outcome and prognostic factors. Oncotarget 2017;8:43228–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schochlin M, Weissinger SE, Brandes AR, et al. A nuclear circularity-based classifier for diagnostic distinction of desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma in digitized histological images. J Pathol Inform 2014;5:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Maher NG, Solinas A, Scolyer RA, et al. Detection of desmoplastic melanoma with dermoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31:2016–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Winnepenninckx V, De Vos R, Stas M, et al. New phenotypical and ultrastructural findings in spindle cell (desmoplastic/neurotropic) melanoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2003;11:319–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sims JR, Wieland CN, Kasperbauer JL, et al. Head and neck desmoplastic melanoma: Utility of sentinel node biopsy. Am J Otolaryngol 2017;38:537–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shaw HM, Quinn MJ, Scolyer RA, et al. Survival in patients with desmoplastic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:e12author reply e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mohebati A, Ganly I, Busam KJ, et al. The role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in the management of head and neck desmoplastic melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:4307–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Murali R, Shaw HM, Lai K, et al. Prognostic factors in cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma: a study of 252 patients. Cancer 2010;116:4130–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wasif N, Gray RJ, Pockaj BA. Desmoplastic melanoma - the step-child in the melanoma family? J Surg Oncol 2011;103:158–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]