Abstract

Background : The Seven Countries Study in the 1960s showed very low mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD) in Japan, which was attributed to very low levels of total cholesterol. Studies of migrant Japanese to the USA in the 1970s documented increase in CHD rates, thus CHD mortality in Japan was expected to increase as their lifestyle became Westernized, yet CHD mortality has continued to decline since 1970. This study describes trends in CHD mortality and its risk factors since 1980 in Japan, contrasting those in other selected developed countries.

Methods : We selected Australia, Canada, France, Japan, Spain, Sweden, the UK and the USA. CHD mortality between 1980 and 2007 was obtained from WHO Statistical Information System. National data on traditional risk factors during the same period were obtained from literature and national surveys.

Results : Age-adjusted CHD mortality continuously declined between 1980 and 2007 in all these countries. The decline was accompanied by a constant fall in total cholesterol except Japan where total cholesterol continuously rose. In the birth cohort of individuals currently aged 50–69 years, levels of total cholesterol have been higher in Japan than in the USA, yet CHD mortality in Japan remained the lowest: >67% lower in men and > 75% lower in women compared with the USA. The direction and magnitude of changes in other risk factors were generally similar between Japan and the other countries.

Conclusions : Decline in CHD mortality despite a continuous rise in total cholesterol is unique. The observation may suggest some protective factors unique to Japanese.

Keywords: Coronary heart disease, international trend, risk factors, total cholesterol, Japan, Western countries

Key Messages

This paper described trends in mortality from coronary heart disease and total cholesterol as well as other risk factors since 1980, highlighting the trends in Japan and contrasting those in other selected developed countries: Australia, Canada, France, Spain, Sweden, the UK and the USA.

Age-adjusted mortality from coronary heart disease continuously declined between 1980 and 2007 in all these countries.

The decline in age-adjusted mortality from coronary heart disease was accompanied by a constant fall in total cholesterol except for Japan where total cholesterol continuously rose.

The direction and magnitude of changes in other risk factors were generally similar between Japan and the other countries.

The observations may suggest some protective factors unique to Japanese in Japan.

Introduction

The Seven Countries Study in the 1960s reported a 5-fold difference in mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD): the lowest in Japan and Southern Europe and the highest in Northern Europe and the USA. 1 The difference in CHD mortality was partly attributed to a marked difference in blood levels of total cholesterol: 4.25 mmol/l in Japan vs.6.20 mmol/lin the USA. The low levels of total cholesterol in Japan were due to their low dietary intake of saturated fat and cholesterol. Based on this and other numerous studies, blood levels of total and low-density-lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol were established as one major risk factor for CHD. Both individual-based diet and drug trials document that lowering levels of total or LDL cholesterol reduces the risk of CHD. 2,3

Studies of migrant Japanese to the USA in the 1970s reported a dramatic increase in CHD rates within one generation of migration. 4 It was thus expected that exposures to more a Westernized lifestyle among native Japanese after World War II (WWII), for example increase in dietary intake of saturated fat, would cause sizeable rise in blood total cholesterol, leading to a considerable increase in CHD rates in Japan. Between 1960 and 1990, dietary intake of fat and cholesterol in Japan more than doubled. 5 The current levels of blood total cholesterol in Japan, especially among individuals born after WWII, are comparable to those in other developed countries, 6 very different from the 2-mmol/l difference in total cholesterol at the time of the Seven Countries Study. Moreover, age-adjusted mortality from other diseases related to Westernized lifestyle, such as colon, breast and prostate cancers, more than doubled during this period. 7 Very surprisingly, age-adjusted CHD mortality in Japan started to decline in1970 as in Western countries, and has remained one of the lowest in developed countries: >67% lower in men and >75% lower in women compared with the USA, 8 accounting partly for the greatest longevity in the world among Japanese. 9 This study describes trends in CHD mortality and its risk factors since 1980, highlighting the trends in Japan and contrasting those in other selected developed countries.

Methods

Data on CHD mortality were obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO) Statistical Information System [ www.who.int/whosis ]. A new WHO standard 10 was used to calculate age-adjusted mortality for men and women aged 35–74 years. To define CHD, we used codes I20–25 in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) and codes 410–414 in ICD-9. To examine the trends, we used 4-year average CHD mortality between 1980 and 2007, that is 1980–83 to 2004–07. To depict the international trend in CHD mortality from 1980 to 2007, we chose Australia, Canada, France, Japan, Spain, Sweden, the UK and the USA.

Data on age-adjusted mean levels of total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, rates of current smokers and body mass index (BMI), as well as age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes, were obtained from recent Global Burden of Disease publications 6,11–14 which describe their trends between 1980 and 2008 in each of the above and other countries. These data are based on extensive search of published and unpublished national health surveys and epidemiological studies, and thus are considered to be the best available data to illustrate and compare the trends across countries in this period.

To compare age- and sex-specific trends in total cholesterol between Japan and the USA, data were obtained from national surveys in each country. 15–18

Results

In 1980–83, Japan had the lowest age-adjusted mortality from CHD; a 6- to 7-fold difference in age-adjusted CHD mortality existed among these countries: 62.4/100 000 in Japan vs 367.0/100 000 in the USA for men and 27.3/100 000 in Japan vs 134.7/100 000 in the USA for women ( Table 1 ). Between 1980–83 and 2004–07, age-adjusted CHD mortality in Japan declined by 26.7% in men and 50.7% in women. The percentage of decline in women in Japan was comparable to that in other countries whereas that in men was less than a half. There remained a 3- to 5-fold difference, that is 45.8/100 000 in Japan vs 150.7/100 000 in the USA for men and 13.5/100 000 in Japan vs 60.6/100 000 in the USA for women ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Trend in age-adjusted mortality from coronary heart disease (/100 000) between 1980–83 and 2004–08 in men (A) and women (B)

|

(A) Men

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980–83 | 1984–87 | 1988–91 | 1992–95 | 1996–99 | 2000–03 | 2004–07 | % change a | |

| UK | 460.3 | 430.5 | 364.7 | 307.4 | 245.3 | 189.7 | 143.7 | −68.8 |

| Australia | 389.3 | 326.9 | 260.1 | 202.7 | 160.3 | 119.5 | 89.5 | −77.0 |

| Sweden | 381.4 | 336.9 | 270.0 | 222.7 | 174.4 | 134.8 | 111.4 | −70.8 |

| USA | 367.0 | 303.3 | 253.1 | 220.8 | 197.5 | 183.7 | 150.7 | −58.9 |

| Canada | 358.2 | 301.7 | 242.2 | 195.9 | 164.9 | 134.8 | 114.6 | −68.0 |

| Spain | 137.4 | 134.7 | 122.6 | 116.5 | 112.2 | 96.1 | 80.9 | −41.4 |

| France | 132.5 | 125.7 | 100.0 | 87.9 | 78.8 | 68.8 | 55.5 | −58.1 |

| Japan | 62.4 | 52.0 | 44.4 | 45.0 | 51.8 | 48.8 | 45.8 | −26.7 |

|

(B) Women

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980–83 | 1984–87 | 1988–91 | 1992–95 | 1996–99 | 2000–03 | 2004–07 | % change a | |

| UK | 154.4 | 150.9 | 132.5 | 111.5 | 88.0 | 65.6 | 46.6 | −69.8 |

| Australia | 140.1 | 121.7 | 96.4 | 74.0 | 55.6 | 40.3 | 26.5 | −81.1 |

| Sweden | 110.2 | 94.6 | 80.1 | 67.9 | 55.1 | 45.9 | 35.0 | −68.3 |

| USA | 134.7 | 117.1 | 99.1 | 88.0 | 80.9 | 75.5 | 60.6 | −55.0 |

| Canada | 120.7 | 101.5 | 82.1 | 67.0 | 55.8 | 44.6 | 37.5 | −68.9 |

| Spain | 39.2 | 36.6 | 33.7 | 31.5 | 28.9 | 24.3 | 19.9 | −49.3 |

| France | 36.9 | 34.1 | 24.9 | 21.6 | 18.5 | 15.5 | 12.0 | −67.7 |

| Japan | 27.3 | 21.6 | 17.4 | 16.6 | 17.6 | 15.2 | 13.5 | −50.7 |

a % change was calculated as the difference between CHD mortality in 1980–83 and 2004–07 divided by CHD mortality in 1980–83. We first calculated age-adjusted CHD mortality in each year from 1980 through 2007. Then we averaged the mortality in 4-year periods, e.g. 1980–83, 1984–87 and so forth. The WHO Statistical Information System did not provide data in 2005 in Australia nor in 2006 and 2007 in Canada; thus we averaged the data in 2004, 2006 and 2007 for Australia and 2004 and 2005 for Canada for CHD mortality in 2004–07 in each country.

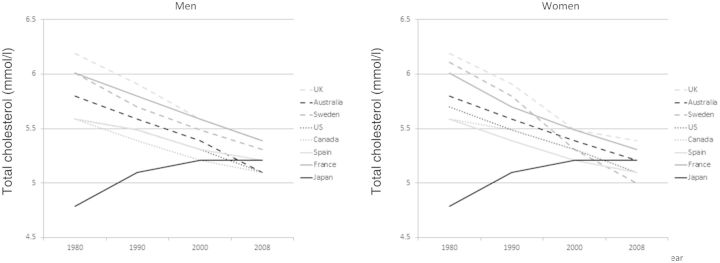

Between 1980 and 2008, age-adjusted mean levels of total cholesterol steadily rose in Japan in striking contrast to constant fall in total cholesterol in all other countries ( Figure 1 ; Supplementary Table 1 , available as Supplementary data at IJE online). The larger part of the risei cholesterol in Japan occurred between 1980 and 1990.

Figure 1.

Trends in age-adjusted levels of total cholesterol in Japan and selected developed countries between 1980 and 2008 by sex (mmol/l). Data are from reference 6. Actual numerical data are in Supplementary Table 1 .

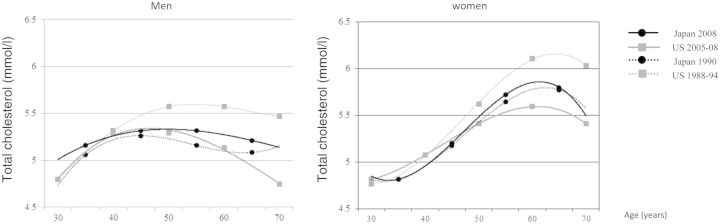

Levels of total cholesterol in individuals aged 50–69 years in 2008 were higher in Japan than in the USA for both sexes ( Figure 2 ; Supplementary Table 2 , available as Supplementary data at IJE online). In this birth cohort, levels of total cholesterol 20 years ago, that is among individuals aged 30–49 years in 1990, were similar between Japan and the USA for both sexes.

Figure 2.

Trends in total cholesterol (mmol/l) in Japan and the USA between 1990 and 2008 by sex from national surveys. The data in Japan of 1990 are from the National Cardiovascular Survey (reference 15) which was recently integrated into the National Health and Nutrition Survey, and the data of 2008 wae from this survey. These surveys in Japan are cross-sectional on a nationally representative sample of the non-institutionalized population of Japan (reference 16). Moreover, in these surveys total cholesterol was measured under the CDC-NHLBI Lipid Standardization Program of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in the USA (references 15 and 17); thus data are directly compared with those in the USA. The data in the USA of 1988–94 and 2005–08 were from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (reference 18). Numerical data were shown in Supplementary Table 2 .

Age-adjusted mean levels of systolic blood pressure continuously fell between 1980 and 2008 both in Japan and in the other countries ( Table 2 ). The magnitude of the fall in Japan during this period was comparable to that in the other countries.

Table 2.

Trend in age-adjusted systolic blood pressure (mmHg) between 1980 and 2008 in selected countries by sex

|

Men |

Women

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2008 | Diff a | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2008 | Diff a | |

| UK | 136.5 | 136.5 | 134.8 | 131.2 | −5.3 | 131.0 | 131.6 | 128.9 | 124.1 | −6.9 |

| 131.2–141.8 | 133.8–139.2 | 132.4–137.1 | 127.5–134.9 | 125.0–136.6 | 128.8–134.5 | 126.5–131.3 | 120.0–128.1 | |||

| Australia | 134.3 | 132.8 | 130.6 | 127.2 | −7.1 | 128.8 | 125.7 | 121.5 | 117.4 | −9.4 |

| 128.2–140.4 | 129.9–135.6 | 127.9–133.3 | 121.3–132.7 | 122.7–135.0 | 122.9–128.7 | 118.6–124.3 | 11.6–122.8 | |||

| Sweden | 138.8 | 134.2 | 132.9 | 131.7 | −7.1 | 132.9 | 129.3 | 125.8 | 122.9 | −10.0 |

| 133.7–144.1 | 131.3–137.1 | 129.9–136.0 | 126.9–137.0 | 126.6–139.0 | 126.1–132.3 | 122.9–128.7 | 117.7–128.5 | |||

| USA | 131.2 | 127.4 | 124.3 | 123.3 | −7.9 | 125.4 | 122.1 | 120.1 | 118.5 | −6.9 |

| 127.2–135.3 | 124.5–130.2 | 121.9–126.6 | 119.8–126.7 | 121.1–129.6 | 119.1–124.9 | 117.7–122.4 | 115.0–122.0 | |||

| Canada | 131.0 | 129.8 | 126.8 | 123.6 | −7.4 | 124.9 | 123.5 | 121.3 | 118.1 | −6.8 |

| 126.2–135.9 | 126.2–133.5 | 122.5–131.5 | 118.0–129.0 | 120.2–129.4 | 120.0–127.1 | 116.5–125.8 | 11.3–124.4 | |||

| Spain | 136.6 | 131.6 | 130.3 | 130.4 | −6.2 | 133.5 | 127.9 | 124.1 | 122.0 | −11.5 |

| 130.6–142.9 | 128.9–134.3 | 127.7–132.9 | 125.8–134.8 | 127.6–140.1 | 125.0–130.6 | 121.4–126.8 | 117.3–126.9 | |||

| France | 138.8 | 134.8 | 132.9 | 131.0 | −7.8 | 132.1 | 127.9 | 123.8 | 120.0 | −12.1 |

| 132.1–145.7 | 131.2–138.4 | 129.5–136.5 | 126.6–135.7 | 124.9–139.7 | 124.0–131.8 | 120.1–127.4 | 115.4–124.6 | |||

| Japan | 136.8 | 132.7 | 131.1 | 130.5 | −6.3 | 131.2 | 127.7 | 124.6 | 122.0 | −9.2 |

| 133.5–140.1 | 130.9–134.4 | 129.3–132.9 | 126.9–133.9 | 128.1–134.3 | 126.0–129.3 | 122.9–126.3 | 118.6–125.2 | |||

Data are expressed as mean and uncertainty interval (reference 11).

a The difference in age-adjusted systolic blood pressure between 1980 and 2008.

Similarly, age-adjusted prevalence of smoking fell between 1980 and 2012 both in Japan and in the other developed countries ( Table 3 ). In men, rates of current smokers in Japan remained highest among these countries during this period: 20–30% higher compared with the USA.

Table 3.

Trend in age-adjusted rates of current smokers (%) between 1980 and 2012 in selected countries by sex

|

Men

|

Women

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1996 | 2006 | 2012 | Diff a | 1980 | 1996 | 2006 | 2012 | Diff a | |

| UK | 38.8 | 30.4 | 25.6 | 23.0 | −15.8 | 38.0 | 29.5 | 23.6 | 20.1 | −17.9 |

| 36.741.0 | 29.5–31.4 | 24.7–26.4 | 20.9–25.2 | 35.6–40.5 | 28.3–30.7 | 22.6–24.6 | 19.0–21.2 | |||

| Australia | 34.3 | 25.6 | 20.8 | 18.3 | −16.0 | 27.3 | 22.6 | 17.2 | 15.4 | −11.9 |

| 31.8–37.2 | 24.3–26.9 | 19.3–22.2 | 16.4–20.1 | 24.3–30.6 | 21.1–24.1 | 15.6–18.9 | 13.5–17.5 | |||

| Sweden | 30.3 | 19.7 | 11.1 | 12.3 | −18.0 | 28.7 | 24.8 | 15.1 | 14.8 | −13.9 |

| 28.5–32.0 | 18.6–20.9 | 10.5–11.8 | 11.0–13.8 | 26.6–30.9 | 23.2–26.4 | 14.1–16.2 | 13.0–16.8 | |||

| USA | 33.2 | 23.1 | 19.7 | 17.2 | −16.0 | 28.3 | 20.1 | 16.4 | 14.3 | −14.0 |

| 29.9–36.7 | 22.2–24.2 | 18.9–20.5 | 16.3–18.2 | 24.2–32.5 | 19.0–21.2 | 15.6–17.3 | 13.3–15.5 | |||

| Canada | 42.3 | 27.4 | 18.1 | 16.7 | −25.6 | 34.1 | 24.6 | 14.3 | 12.8 | −21.3 |

| 39.0–45.5 | 26.0–29.0 | 17.0–19.2 | 15.4–18.3 | 30.4–37.8 | 22.9–26.2 | 13.3–15.4 | 11.5–14.1 | |||

| Spain | 44.4 | 41.0 | 31.7 | 29.5 | −14.9 | 28.3 | 27.7 | 25.7 | 23.2 | −5.1 |

| 39.4–49.6 | 38.9–43.0 | 29.9–33.3 | 26.9–32.2 | 22.8–34.1 | 25.7–29.7 | 23.7-27.6 | 20.3–26.4 | |||

| France | 41.5 | 37.9 | 33.3 | 34.4 | −7.1 | 18.8 | 30.1 | 27.0 | 27.7 | +8.9 |

| 38.6–44.7 | 35.8–39.9 | 31.2–35.6 | 30.8-38.0 | 16.4-21.5 | 28.0-32.3 | 24.6-29.4 | 24.0-31.6 | |||

| Japan | 60.8 | 51.9 | 40.9 | 35.3 | −25.5 | 13.0 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 11.2 | −1.8 |

| 57.9–64.0 | 49.6–55.1 | 38.3–43.8 | 32.4–38.5 | 115–14.7 | 11.7–14.0 | 12.0–14.3 | 9.6–13.0 | |||

Data are expressed as mean and uncertainty interval (reference 14).

a The difference in age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes between 1980 and 2012.

In most of the countries, including Japan, age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes rosefrom 1980 to 2008 ( Table 4 ). During this period, the prevalence in Japan rose by 3.4% in men and by 1.4% in women. The age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes in Japan in 2008 was similar to that in France and was lower compared with the USA and Canada.

Table 4.

Trend in age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes (%) between 1980 and 2008 in selected countries by sex

|

Men

|

Women

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2008 | Diff a | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2008 | Diff a | |

| UK | 8.1 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.8 | -0.3 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 0.0 |

| 2.0–19.2 | 4.5–11.2 | 4.7–10.6 | 3.8–13.4 | 1.3–14.4 | 3.5–8.8 | 3.7–8.3 | 2.7–10.1 | |||

| Australia | 5.9 | 6.7 | 8.3 | 9.6 | +3.7 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 6.0 | 6.7 | +2.1 |

| 2.5–11.0 | 3.6–10.7 | 5.4–12.2 | 4.4–16.9 | 2.0–8.6 | 2.6–8.1 | 3.8–8.8 | 2.9–12.2 | |||

| Sweden | 6.9 | 6.0 | 6.6 | 8.1 | +1.2 | 7.5 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 6.0 | −1.5 |

| 1.7–16.6 | 3.6–9.1 | 3.6–10.6 | 2.5–17.0 | 0.6–12.5 | 4.1–10.4 | 3.1–9.7 | 1.6–13.6 | |||

| USA | 6.1 | 8.1 | 10.3 | 12.6 | +6.5 | 5.1 | 6.4 | 7.6 | 9.1 | +2.8 |

| 2.9–10.7 | 2.7–16.8 | 7.2–14.1 | 8.1–18.1 | 2.4–8.9 | 3.9–9.8 | 5.3–10.4 | 5.7–13.3 | |||

| Canada | 7.6 | 8.1 | 9.4 | 10.9 | +3.3 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 8.3 | +2.8 |

| 1.1–21.2 | 2.7–16.8 | 3.4–19.1 | 2.5–26.3 | 0.7–16.7 | 1.8–13.7 | 2.1–15.6 | 1.6–20.9 | |||

| Spain | 5.2 | 5.5 | 7.8 | 11.0 | +5.2 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 6.2 | 8.8 | +4.4 |

| 1.0–14.0 | 3.0–8.8 | 5.3–11.0 | 5.9–18.5 | 0.6–12.5 | 2.4–7.3 | 4.1–8.8 | 4.5–15.2 | |||

| France | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.1 | 7.2 | +0.1 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.3 | −0.6 |

| 1.2–19.2 | 3.3–12.3 | 4.3–10.8 | 3.3–12.6 | 0.7–14.6 | 2.3–9.1 | 2.7–7.6 | 1.9–7.8 | |||

| Japan | 3.8 | 4.9 | 6.3 | 7.2 | +3.4 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 4.7 | +1.4 |

| 1.0–8.7 | 3.5–6.5 | 4.6–8.2 | 4.5–10.4 | 1.0–7.2 | 3.0–5.6 | 3.6–6.5 | 2.9–7.0 | |||

Data are expressed as mean and uncertainty interval (reference 13).

a The difference in age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes between 1980 and 2008.

Age-adjusted levels of BMI rose between 1980 and 2008 in all the countries for both sexes ( Table 5 ). Levels of BMI in Japan rose during this period by 1.4 kg/m 2 in men and 0.6 kg/m 2 in women; the mean BMI and prevalence of obesity remained much lower in Japan compared with those in the other countries.

Table 5.

Trend in age-adjusted levels of body mass index (kg/m 2 ) between 1980 and 2008 in selected countries by sex

|

Men

|

Women

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2008 | Diff a | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2008 | Diff a | |

| UK | 24.7 | 25.6 | 26.6 | 27.4 | +2.7 | 24.2 | 25.2 | 26.2 | 26.9 | +2.7 |

| 23.9–25.6 | 25.2–26.0 | 26.4–26.9 | 26.9–27.9 | 23.2–25.2 | 24.8–25.7 | 25.9–26.6 | 26.3–27.6 | |||

| Australia | 24.9 | 25.8 | 26.7 | 27.6 | +2.7 | 23.6 | 24.9 | 26.0 | 26.9 | +3.3 |

| 24.3–25.6 | 25.4–26.2 | 26.4–27.1 | 27.0–28.1 | 22.8–24.4 | 24.4–25.4 | 25.6–26.5 | 26.2–27.6 | |||

| Sweden | 24.7 | 25.2 | 25.8 | 26.4 | +1.7 | 24.4 | 24.6 | 24.9 | 25.1 | +0.7 |

| 23.7–25.8 | 24.8–25.6 | 25.4–26.1 | 25.6–27.2 | 23.0–25.7 | 24.0–25.2 | 24.4–25.5 | 24.1–26.2 | |||

| USA | 25.5 | 26.6 | 27.7 | 28.5 | +3.0 | 25.0 | 26.3 | 27.5 | 28.3 | +3.3 |

| 25.0–26.0 | 26.2–27.0 | 27.4–28.0 | 28.0–28.9 | 24.3–25.8 | 25.8–26.8 | 27.1–27.9 | 27.7–28.9 | |||

| Canada | 25.2 | 26.1 | 27.0 | 27.5 | +2.3 | 24.1 | 25.1 | 26.1 | 26.7 | +2.6 |

| 24.6–25.8 | 25.7–26.5 | 26.5–27.4 | 27.0–28.0 | 23.3–24.9 | 24.6–25.6 | 25.6–26.7 | 26.0–27.4 | |||

| Spain | 25.3 | 25.7 | 26.6 | 27.5 | +2.2 | 25.2 | 25.5 | 26.0 | 26.3 | +1.1 |

| 24.2–26.6 | 25.3–26.2 | 26.3–27.0 | 26.8–28.2 | 23.8–26.5 | 24.9–26.0 | 25.5–26.4 | 25.4–27.2 | |||

| France | 24.7 | 25.0 | 25.4 | 25.9 | +1.2 | 24.1 | 24.4 | 24.7 | 24.8 | +0.7 |

| 23.5-26.0 | 24.3-25.7 | 24.8-26.0 | 252-26.5 | 22.6-25.7 | 23.5-25.3 | 23.9-25.4 | 23.9-25.7 | |||

| Japan | 22.1 | 22.4 | 23.1 | 23.5 | +1.4 | 21.3 | 21.6 | 21.9 | 21.9 | +0.6 |

| 21.4-22.8 | 22.1-22.7 | 22.9-23.3 | 23.1-23.9 | 20.5-22.1 | 21.3-22.0 | 21.6-22.2 | 21.3-22.4 | |||

Data are expressed as mean and uncertainty interval (reference 12).

a The difference in age-adjusted body mass index between 1980 and 2008.

Discussion

Our study illustrated opposite directions of trends in population-levels of total cholesterol between Japan and Western countries, despite decline in age-adjusted CHD mortality between 1980 and 2008 in all these countries. Our study also showed that the magnitude of changes in other major risk factors during this period was generally similar across these countries.

The declining trend in CHD mortality in these countries that started around 1970 is attributable to two factors: a better population profile of risk factors which leads to reduced CHD incidence and improved treatment for CHD. The decline in CHD mortality between the 1980s and 2000s in Canada, 19 Italy, 20 Sweden, 21 the UK 22 and the USA 23 is attributable to reductions in major risk factors by 40–60% and to improved treatment by about 40%. The fall in population-levels of total cholesterol is a major contributor to the decline in CHD mortality. CHD mortality in Japan started to decline in 1970: the fact that population-levels of total cholesterol steadily and markedly rose in Japan during the past five decades is counterintuitive.

Substantial increase in CHD mortality occurred in the first half of the 20th century in Western countries and is now taking place in developing countries. 24 Although data are limited on specific causes for the increase, a recent study in Beijing, China, conducted between 1984 and 1999, shows that the rise in population-levels of total cholesterol accounts for 77% of the increase in CHD mortality. 25 During this period, CHD mortality in China increased by 50% in men and 27% in women; population-levels of total cholesterol rose by 1 mmol/l. The magnitude of rise in total cholesterol is similar to that the Japanese experienced between the 1960s and 1990s.

The low CHD mortality in Japan is not due to a misclassification of cause of death or a competing risk. Incidence of myocardial infarction in multiple registries in Japan, using the WHO MONICA criteria, was much lower than in registries in all industrialized countries or even China, according to the WHO MONICA study. 26 Though stroke mortality in Japan was highest in developed countries in the 1960s, the mortality dropped by almost 80% between 1965 through 1990. 26 Current stroke mortality is similar to that in other developed countries. 9 Moreover, age-adjusted total mortality in Japan is lower by 20% in men and 40% in women compared with the USA. 8

The low CHD mortality in Japan is unlikely to be due to genetics. Studies of Japanese migrants to the USA documented a dramatic increase in CHD rates. 4 Additionally, Japanese Americans had higher levels of atherosclerosis, a major underlying cause of CHD, than White Americans. We compared well-established biomarkers of atherosclerosis, coronary artery calcification and carotid intima-media thickness, in population-based samples of middle-aged native Japanese, White Americans and third-generation Japanese Americans without ethnic admixture. 27 Despite a similar profile of risk factors, Japanese Americans had higher levels of atherosclerosis compared with not only native Japanese but also White Americans.

CHD mortality in Japan increased between 1992–95 and 1996–99 in both sexes. The increase is largely due to changes in coding practice for death certification. Before the 10th revision of the ICD was introduced in 1995, the Ministry of Health in Japan issued in 1994 guidance not to put heart failure as primary cause of death in terminal stage or sudden death. As a result, mortality from heart failure decreased by 60–70% and mortality from CHD increased by 20–30% between 1993 and 1995. 28,29 Taking the change into consideration, the decline in age-adusted CHD mortality in women was rather similar before and after 1995, whereas that in men appeared to be attenuated after 1995 ( Supplementary Figure 1 , available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Therefore it is of critical importance to carefully monitor trends in CHD mortaliy in men in Japan.

Our observation: in Japan the decline in CHD mortality, despite a continuous and marked rise in total cholesterol, is in accordance with a recent report from the Hisayama study. 30 The study consists of a series of population-based cohorts of several thousand subjects in each decade since the 1960s in Hisayama, Japan. 30 The study revealed no increase in age-adjusted CHD incidence or mortality between the cohorts in the 1960s through 2000s despite a substantial rise in age-adjusted total cholesterol (1.2 mmol/l).

Is total cholesterol not a risk factor for CHD in the Japanese? Prospective cohort studies in Japan have consistently reported that total cholesterol is an independent risk factor for CHD. 31,32 The relative risk of CHD associated with total cholesterol in Japan 33,34 is similar to that reported in Western countries 35 as with blood pressure, smoking and diabetes. 33,35–38 A randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in Japan 39 of the effect of statins on CHD shows a similar relative-risk reduction as reported in Western countries. 40 These lines of evidence confirm that total cholesterol is an independent risk factor in Japan.

Is the difference in CHD rates between Japan and the USA due largely to a cohort effect? We compared population-levels of total cholesterol in individuals born after WWII, that is individuals currently aged 50–69 years, between Japan and the USA ( Figure 2 ). The current levels of total cholesterol were higher in Japan than in the USA whereas the levels were comparable 20 years ago. Thus, in this birth cohort, exposure to total cholesterol is higher in Japanese.

Some 41,42 (including one in children 43 ) but not all 44 studies reported that levels of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) are higher in Japan than in the USA. Higher levels of HDL-C in Japanese are partly due to genetics. 45 Though low HDL-C (< 1.0 mmol/l) is considered to be a risk factor for CHD, 46,47 the National Lipid Association has recently posed questions about protective roles of high levels of HDL-C. 46 Furthermore, little evidence exists in studies in Japan to show that high levels of HDL-C are protective against CHD 48 or atherosclerosis. 42 Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that genetic mechanisms that raise HDL-C do not lower the risk of CHD. 49 Thus, clinical significance of higher HDL-C in Japan remains to be elucidated.

Comparing the trends in non-HDL-C or LDL-C from 1980 through 2008 may be informative, especially because non-HDL-C is superior to total cholesterol in predicting CHD. 50 Unfortunately such data do not exist, yet it is imperative to point out that a relative risk of total cholesterol associated with CHD in Japan is similar to that in the USA at every level of total cholesterol. 51 Furthermore, we have shown that among men aged 40–49 years in Japan (born after WWII), who are more exposed to Westernized lifestyle than older age groups, levels of non-HDL-C and LDL-C were similar to those in the USA, yet levels of atherosclerosis were significantly lower in Japan. 42 Of note, prevalences of hypertension, smoking and diabetes were higher in Japan than in the USA in this study. We also compared levels of non-HDL-C and LDL-C between Japan and the USA around 2008 using the data from national surveys, and found that the levels of both non-HDL-C and LDL-C were comparable (data not shown). Therefore it is unlikely that the differences in non-HDL-C or LDL-C play a major role in explaining the low CHD mortality in Japan.

The direction and magnitude of the changes in risk factors other than total cholesterol are generally similar among these countries. One exception is smoking in men in Japan, where rates dropped by 25.5% between 1980 and 2012. One way to examine the extent the change in rates of current smokers contributes to the change in CHD mortality is to examine the difference in population-attributable risk fraction (PARF) between 1980 and 2012. 19,23,52 The difference in PARF in Japan, however, was very similar to that in most developed countries ( Supplementary Table 3 , available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Obesity is a risk factor for CHD. 53 Much lower levels of BMI in Japan compared with Western countries may contribute to the low CHD mortality in Japan. The association of BMI with CHD, however, is largely mediated through risk factors: blood pressure, lipids and diabetes. 53 Levels of blood pressure have been higher in Japan than in the USA. 11 Japanese develop diabetes and metabolic syndrome at lower levels of BMI compared with Caucasians. 54,55 There is no evidence that lower BMI in Japan is due to higher levels of physical activity. 56–58 Thus the difference in BMI alone is unlikely to account for the difference in CHD mortality between Japan and the other developed countries.

These results suggest that some protective factors unique to Japanese in Japan account for their low CHD mortality. Alternatively, these results may suggest that there are higher levels of risk factors for CHD in other countries compared with Japan, such as meat intake 59 and sugar-sweetened beverages. 60 CHD mortality, however, declined during this period so that any adverse effects of these nutrients must be balanced by factors that decreased mortality.

A possible hypothesis for the difference in CHD mortality between Japan and Western countries is common source exposure in the diet that affects most of the population in Japan but is rare in Western diets. Dietary intake of fruits and vegetables, 58,61 vitamins A, C and E and β-carotene are comparable between the USA and Japan. 56,62 The Japanese diet compared with the US diet is relatively low in saturated fat, but very high in cholesterol, sodium and carbohydrate. 56,62 The most likely common source in the Japanese diet is a markedly high intake of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCn3PUFAs) and soy isoflavones. 56,62,63 In Japan, dietary intake of LCn3PUFAs (> 1000 mg/day) is >10 times higher, and that of isoflavones (25–50 mg/day) is >20 times higher compared with in the USA. 64 LCn3PUFAs 65 and isoflavones 66 possess various biological properties related to anti-atherosclerosis. Large prospective cohort studies in Japan document that dietary intake of both LCn3PUFAs 67 and isoflavones 68 has significant inverse associations with incident CHD.

Prospective cohort studies in Western countries document that compared with little or no intake of fish, modest consumption, such as 25–30 g/day of fish, lowers CHD death rates by 20–30% 69 but not CHD incidence. 70–72 This benefit is believed to be due to the anti-arrhythmic properties of LCn3PUFAs. 69 In contrast, Japanese consume an average of >70 g/day of fish and studies in Japan document a significant effect of LCn3PUFAs on CHD incidence. 67,73 Though recent RCTs of LCn3PUFAs on CHD among high-risk individuals in Western countries have all failed to show reduction in CHD, 74–77 the doses of LCn3PUFAs administered in these RCTs, that is 300–900 mg/day, do not even reach the average dietary intake of LCn3PUFAs among the Japanese of >1000 mg/day. An RCT of LCn3PUFAs of 1800 mg/day in Japan demonstrated a significant 19% reduction in coronary events. 73 Importantly, the dose of 1800 mg/day was on top of their average dietary intake of >1000 mg/day. Previously we reported that serum levels of LCn3PUFAs had a significant inverse association with atherosclerosis among Japanese but not in North Americans 27 and that much higher levels of serum LCn3PUFAs in the Japanese significantly contributed to the cross-sectional and longitudinal difference in atherosclerosis between Japanese and Americans. 27,78 These observations may suggest that LCn3PUFAs, at the levels that Japanese consume, have anti-atherogenic properties. 79

Limitations include ecological study in design, thus cautious interpretations are appropriate. Ecological fallacy occurs when inferences are made from group data to individual level, 80–82 yet the current study did not infer causality at the individual level. Atherosclerosis has a long incubation period, and short-term changes in its risk factors do not necessarily translate into the change in CHD rates. Therefore we analysed the almost 30-year trend in CHD mortality and its risk factors. Data sources of risk factors are not necessarily from national surveys, yet most of these data of Japan and the USA are based on the national surveys.

In conclusion, we observed that between 1980 and 2008, age-adjusted CHD mortality in Japan declined as in other developed countries, despite a continuous and marked rise in total cholesterol in sharp contrast to a constant fall in total cholesterol in other developed countries. The lower CHD mortality in Japan compared with the USA is very unlikely to be due to the difference in trends in other CHD risk factors, cohort effects, misclassification of causes of death, competing risk with other diseases or genetics. The observation may suggest some protective factors unique to Japanese which merit further research.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01 HL68200].

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Verschuren WM, Jacobs DR, Bloemberg BP, et al. . Serum total cholesterol and long-term coronary heart disease mortality in different cultures. Twenty-five-year follow-up of the Seven Countries study . JAMA 1995. ; 274 : 131 – 36 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hooper L, Summerbell CD, Thompson R, et al. . Reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease . Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011. ; 5 : CD002137 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaborators . Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90 056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins . Lancet 2005. ; 366 : 1267 – 78 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Worth RM, Kato H, Rhoads GG, Kagan K, Syme SL . Epidemiologic studies of coronary heart disease and stroke in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii and California: mortality . Am J Epidemiol 1975. ; 102 : 481 – 90 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yoshiike N, Matsumura Y, Iwaya M, Sugiyama M, Yamaguchi M . National Nutrition Survey in Japan . J Epidemiol 1996. ; 6 : S189 – 200 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Farzadfar F, Finucane MM, Danaei G, et al. . National, regional, and global trends in serum total cholesterol since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 321 country-years and 3·0 million participants . Lancet 2011. ; 377 : 578 – 86 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Qiu D, Katanoda K, Marugame T, Sobue T . A joinpoint regression analysis of long-term trends in cancer mortality in Japan (1958-2004) . Int J Cancer 2009. ; 124 : 443 – 48 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. . Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2014 Update: A report from the American Heart Association . Circulation 2014. ; 129 : e28 – e292 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ikeda N, Saito E, Kondo N, et al. . What has made the population of Japan healthy? Lancet 2011. ; 378 : 1094 – 105 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Lozano R, Inoue M . Age Standardization of Rates: A New WHO Standard . Geneva: : World Health Organization; , 2001. . [Google Scholar]

- 11. Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lin JK, et al. . National, regional, and global trends in systolic blood pressure since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 786 country-years and 5·4 million participants . Lancet 2011. ; 377 : 568 – 77 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, et al. . National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9·1 million participants . Lancet 2011. ; 377 : 557 – 67 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, et al. . National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2.7 million participants . Lancet 2011. ; 378 : 31 – 40 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ng M, Freeman MK, Fleming TD, et al. . Smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption in 187 countries, 1980-2012 . JAMA 2014. ; 311 : 183 – 92 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Okamura T, Tanaka H, Miyamatsu N, et al. . The relationship between serum total cholesterol and all-cause or cause-specific mortality in a 17.3-year study of a Japanese cohort . Atherosclerosis 2007. ; 190 : 216 – 23 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wakita Asano A, Miyoshi M, Arai Y, Yoshita K, Yamamoto S, Yoshiike N . Association between vegetable intake and dietary quality in Japanese adults: a secondary analysis from the National Health and Nutrition Survey, 2003 . J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2008. ; 54 : 384 – 91 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakamura M, Sato S, Shimamoto T, Konishi M, Yoshiike N . Establishment of long-term monitoring system for blood chemistry data by the national health and nutrition survey in Japan . J Atheroscler Thromb 2008. ; 15 : 244 – 49 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States , 2011. : With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health . Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department Printing Office, 2012 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wijeysundera HC, Machado M, Farahati F, et al. . Association of temporal trends in risk factors and treatment uptake with coronary heart disease mortality, 1994-2005 . JAMA 2010. ; 303 : 1841 – 47 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Palmieri L, Bennett K, Giampaoli S, Capewell S . Explaining the decrease in coronary heart disease mortality in Italy between 1980 and 2000 . Am J Public Health 2010. ; 100 : 684 – 92 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bjorck L, Rosengren A, Bennett K, Lappas G, Capewell S . Modelling the decreasing coronary heart disease mortality in Sweden between 1986 and 2002 . Eur Heart J 2009. ; 30 : 1046 – 56 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hardoon SL, Whincup PH, Lennon LT, Wannamethee SG, Capewell S, Morris RW . How much of the recent decline in the incidence of myocardial infarction in British men can be explained by changes in cardiovascular risk factors?: Evidence from a prospective population-based study . Circulation 2008. ; 117 : 598 – 604 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. . Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980-2000 . N Engl J Med 2007. ; 356 : 2388 – 98 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Finegold JA, Asaria P, Francis DP . Mortality from ischaemic heart disease by country, region, and age: statistics from World Health Organisation and United Nations . Int J Cardiol 2013. ; 168 : 934 – 45 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Critchley J, Liu J, Zhao D, Wei W, Capewell S . Explaining the increase in coronary heart disease mortality in Beijing between 1984 and 1999 . Circulation 2004. ; 110 : 1236 – 44 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ueshima H, Sekikawa A, Miura K, et al. . Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in Asia: a selected review . Circulation 2008. ; 118 : 2702 – 09 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sekikawa A, Curb JD, Ueshima H, et al. . Marine-derived n-3 fatty acids and atherosclerosis in Japanese, Japanese-American, and white men: a cross-sectional study . J Am Coll Cardiol 2008. ; 52 : 417 – 24 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saito I, Ozawa H, Aono H, Ikebe T, Yamashita T . [Change of the number of heart disease deaths according to the revision of the death certificates in Oita city] . [Nihon koshu eisei zasshi] Japan J Public Health 1997. ; 44 : 874 – 79 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saito I, Aono H, Ikebe T, Ozawa H, Yamashita T . Change in the mortality statistics for heart disease in Japan: an influence of the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases . [In Japanese.] Japanese Journal of Cardiovascular Disease Prevention 1998. ; 33 : 257 – 65 . [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hata J, Ninomiya T, Hirakawa Y, et al. . Secular trends in cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in Japanese: half-century data from the Hisayama study (1961-2009) . Circulation 2013. ; 128 : 1198 – 205 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Iso H . Changes in coronary heart disease risk among Japanese . Circulation 2008. ; 118 : 2725 – 29 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sekikawa A, Willcox B, Usui T, et al. . Do differences in risk factors explain the lower rates of coronary heart disease in Japanese versus U.S. women? J Women's Health 2013. ; 22 : 966 – 77 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tanabe N, Iso H, Okada K, et al. . Serum total and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and the risk prediction of cardiovascular events – the JALS-ECC . Circ J 2010. ; 74 : 1346 – 56 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ishibashi S, et al. . Absolute risk of cardiovascular disease and lipid management targets . J Atheroscler Thromb 2013. ; 20 : 689 – 97 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Martin MJ, Hulley SB, Browner WS, Kuller LH, Wentworth D . Serum cholesterol, blood pressure, and mortality: implications from a cohort of 361,662 men . Lancet 1986. ; 2 : 933 – 36 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van den Hoogen PCW, Feskens EJM, Nagelkerke NJD, et al. . The relation between blood pressure and mortality due to coronary heart disease among men in different parts of the world . N Engl J Med 2000. ; 342 : 1 – 8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jacobs DR, Jr, Adachi H, Mulder I, et al. . Cigarette smoking and mortality risk: twenty-five-year follow-up of the Seven Countries Study . Arch Intern Med 1999. ; 159 : 733 – 40 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. NIPPON DATA80 Reserach Group . Risk assessment chart for death from cardiovascular disease based on a 19-year follow-up study of a Japanese representative population NIPPON DATA80 . Circ J 2006. ; 70 : 1249 – 55 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nakamura H, Arakawa K, Itakura H, et al. . Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with pravastatin in Japan (MEGA Study): a prospective randomised controlled trial . Lancet 2006. ; 368 : 1155 – 63 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists C . The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials . Lancet 2012. ; 380 : 581 – 90 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ueshima H, Iida M, Shimamoto T, et al. . High-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels in Japan . JAMA 1982. ; 247 : 1985 – 87 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sekikawa A, Ueshima H, Kadowaki T, et al. . Less subclinical atherosclerosis in Japanese men in Japan than in White men in the United States in the post-World War II birth cohort . Am J Epidemiol 2007. ; 165 : 617 – 24 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dwyer T, Iwane H, Dean K, et al. . Differences in HDL cholesterol concentrations in Japanese, American, and Australian children . Circulation 1997. ; 96 : 2830 – 36 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ohara K, Klag MJ, Sakai Y, Whelton PK, Itoh I, Comstock GW . Factors associated with high density lipoprotein cholesterol in Japanese and American telephone executives . Am J Epidemiol 1991. ; 134 : 137 – 48 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weissglas-Volkov D, Pajukanta P . Genetic causes of high and low serum HDL-cholesterol . J Lipid Res 2010. ; 51 : 2032 – 57 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Toth PP, Barter PJ, Rosenson RS, et al. . High-density lipoproteins: a consensus statement from the National Lipid Association . J Clin Lipidol 2013. ; 7 : 484 – 525 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ishibashi S, et al. . Diagnostic criteria for dyslipidemia . J Atheroscler Thromb 2013. ; 20 : 655 – 60 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kitamura A, Iso H, Naito Y, et al. . High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and premature coronary heart disease in urban Japanese men . Circulation 1994. ; 89 : 2533 – 39 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M, et al. . Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study . Lancet 2012. ; 380 : 572 – 80 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Blaha MJ, Blumenthal RS, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA . The importance of non-HDL cholesterol reporting in lipid management . J Clin Lipidol 2008. ; 2 : 267 – 73 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hata Y, Mabuchi H, Saito Y, et al. . Report of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Hyperlipidemia in Japanese adults . J Atheroscler Thromb 2002. ; 9 : 1 – 27 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Unal B, Critchley JA, Capewell S . Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in England and Wales between 1981 and 2000 . Circulation 2004. ; 109 : 1101 – 07 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wormser D, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, et al. . Separate and combined associations of body-mass index and abdominal adiposity with cardiovascular disease: collaborative analysis of 58 prospective studies . Lancet 2011. ; 377 : 1085 – 95 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. . Harmonizing the Metabolic Syndrome: A Joint Interim Statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity . Circulation 2009. ; 120 : 1640 – 45 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fujimoto W . Diabetes in Asian and Pacific Islander Americans . In: Harris M, Cowie CC, Stern M, Boyko E, Reiber G, Bennett P. (eds). Diabetes in America . 2nd edn . Bethesda, MD: : National Institutes of Health; , 1995 . [Google Scholar]

- 56. Stamler J, Elliott P, Dennis B, et al. . INTERMAP: background, aims, design, methods, and descriptive statistics (nondietary) . J Hum Hypertension 2003. ; 17 : 591 – 608 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tudor-Locke C, Johnson WD, Katzmarzyk PT . Accelerometer-determined steps per day in US adults . Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009. ; 41 : 1384 – 91 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare . Report from the National Health and Nutrition Survey, 2011. (In Japanese.) 2012 http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/eiyou/dl/h23-houkoku.pdf (10 July 2015, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sinha R, Cross AJ, Graubard BI, Leitzmann MF, Schatzkin A . Meat intake and mortality: a prospective study of over half a million people . Arch Intern Med 2009. ; 169 : 562 – 71 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Hu FB . Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk . Circulation 2010. ; 121 : 1356 – 64 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. US Enviromnetal Protection Aency (EPA). Exposure Factors Handbook: 2011. Washington, DC: National Center for Environmental Assessment, 2011.

- 62. Stamler J, Elliott P, Chan Q ; for the INTERMAP Research Group . Intermap Appendix Tables . J Hum Hypertension 2003. ; 17 : 665 – 775 . [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L . Components of a cardioprotective diet . Circulation 2011. ; 123 : 2870 – 91 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Klein MA, Nahin RL, Messina MJ, et al. . Guidance from an NIH Workshop on Designing, Implementing, and Reporting Clinical Studies of Soy Interventions . J Nutr 2010. ; 140 : S1192 – 204 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Calder PC, Yaqoob P . Marine omega-3 fatty acids and coronary heart disease . Curr Opin Cardiol 2012. ; 27 : 412 – 19 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Rimbach G, Boesch-Saadatmandi C, Frank J, et al. . Dietary isoflavones in the prevention of cardiovascular disease – a molecular perspective . Food Chem Toxicol 2008. ; 46 : 1308 – 19 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Iso H, Kobayashi M, Ishihara J, et al. . Intake of fish and n3 fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease among Japanese: The Japan Public Health Center-Based (JPHC) Study Cohort I . Circulation 2006. ; 113 : 195 – 202 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kokubo Y, Iso H, Ishihara J, et al. . Association of dietary intake of soy, beans, and isoflavones with risk of cerebral and myocardial infarctions in Japanese populations: The Japan Public Health Center Based (JPHC) Study Cohort I . Circulation 2007. ; 116 : 2553 – 62 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mozaffarian D, Rimm EB . Fish intake, contaminants, and human health: evaluating the risks and the benefits . JAMA 2006. ; 296 : 1885 – 99 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lemaitre RN, King IB, Mozaffarian D, Kuller LH, Tracy RP, Siscovick DS . n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids, fatal ischemic heart disease, and nonfatal myocardial infarction in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study . Am J Clin Nutr 2003. ; 77 : 319 – 25 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mozaffarian D, Lemaitre RN, King IB, et al. . Plasma phospholipid long-chain ω-3 fatty acids and total and cause-specific mortality in older adults: a cohort study . Ann Intern Med 2013. ; 158 : 515 – 25 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Morris MC, Manson JE, Rosner B, Buring JE, Willett WC, Hennekens CH . Fish consumption and cardiovascular disease in the Physicians' Health Study: A prospective study . Am J Epidemiol 1995. ; 142 : 166 – 75 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, et al. . Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised open-label, blinded endpoint analysis . Lancet 2007. ; 369 : 1090 – 98 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kromhout D, Giltay EJ, Geleijnse JM . n–3 Fatty acids and cardiovascular events after myocardial infarction . N Engl J Med 2010. ; 363 : 2015 – 26 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Galan P, Kesse-Guyot E, Czernichow S, Briancon S, Blacher J, Hercberg S . Effects of B vitamins and omega 3 fatty acids on cardiovascular diseases: a randomised placebo controlled trial . BMJ 2010. ; 341 : c6273 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. The ORIGIN Trial Investigators . n-3 Fatty acids and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with dysglycemia . N Engl J Med 2012. ; 367 : 309 – 19 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Roncaglioni MC, Tombesi M, Avanzini F, et al. . n-3 fatty acids in patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors . N Engl J Med 2013. ; 368 : 1800 – 08 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sekikawa A, Miura K, Lee S, et al. . Long chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and incidence rate of coronary artery calcification in Japanese men in Japan and white men in the USA: population based prospective cohort study . Heart 2014. ; 100 : 569 – 73 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sekikawa A, Doyle MF, Kuller LH . Recent findings of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCn-3 PUFAs) on atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease (CHD) contrasting studies in Western countries to Japan. TrendsCardiovasc Med 2015; 25 :717–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Susser M . The logic in ecological: II. The logic of design . Am J Public Health 1994. ; 84 : 830 – 35 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Schwartz S . The fallacy of the ecological fallacy: the potential misuse of a concept and the consequences . Am j Public Health 1994. ; 84 : 819 – 24 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Susser M . The logic in ecological: I. The logic of analysis . Am J Public Health 1994. ; 84 : 825 – 29 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.