Abstract

Craniofacial muscle pain, such as spontaneous pain and bite-evoked pain, are major symptoms in patients with temporomandibular disorders and infection. However, the underlying mechanisms of muscle pain, especially mechanisms of highly prevalent spontaneous pain, are poorly understood. Recently, we reported that transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) contributes to spontaneous pain but only marginally contributes to bite-evoked pain during masseter inflammation. Here, we investigated the role of transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) in spontaneous and bite-evoked pain during masseter inflammation, and dissected the relative contributions of TRPA1 and TRPV1. Masseter inflammation increased mouse grimace scale (MGS) scores and face wiping behaviors. Pharmacological or genetic inhibition of TRPA1 significantly attenuated MGS but not face wiping behaviors. MGS scores were also attenuated by scavenging putative endogenous ligands for TRPV1 or TRPA1. Simultaneous inhibition of TRPA1 by AP18 and TRPV1 by AMG9810 in masseter muscle resulted in robust inhibition of both MGS and face wiping behaviors. Administration of AP18 or AMG9810 to masseter muscle induced conditioned place preference (CPP). The extent of CPP following simultaneous administration of AP18 and AMG9810 was greater than that induced by the individual antagonists. In contrast, inflammation-induced reduction of bite force was not affected by the inhibition of TRPA1 alone or in combination with TRPV1. These results suggest that simultaneous inhibition of TRPV1 and TRPA1 produces additive relief of spontaneous pain, but does not ameliorate bite-evoked pain during masseter inflammation. Our results provide further evidence that distinct mechanisms underlie spontaneous and bite-evoked pain from inflamed masseter muscle.

Keywords: muscle pain, inflammation, TRP channels, trigeminal pain

INTRODUCTION

Pain arising from masticatory muscle is complex, involving a range of pain symptoms including tenderness, soreness, and bite-evoked pain. Infection, bruxism, or a chronic pain syndrome as might be caused by a temporomandibular joint disorder cause different pain symptoms involving the masticatory muscles (Mandel, 1997; Castrillon et al., 2008; Dawson, 2013). However, management strategies for these conditions are often ineffective, and development of novel mechanism-based methods to treat craniofacial muscle pain is needed.

Among different pain symptoms, spontaneous pain is a major clinical problem. Spontaneous pain occurs without external stimuli (either mechanical or thermal), and the pain characteristically persists unless the etiologic pathology is resolved. In the clinic, self-reported levels of global pain, including spontaneous ongoing pain, are a primary means for assessing the extent of pain and evaluating effectiveness of treatment (Litcher-Kelly et al., 2007). Spontaneous pain and evoked pain are thought to be mediated by distinct peripheral and central neural mechanisms (Parks et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2017). Since preclinical models of pain mostly measure behaviors associated with evoked-pain, less is known regarding mechanisms underlying spontaneous pain. Thus, to improve clinical management of overall pain symptoms, it is critical to understand the mechanisms of non-evoked pain. Recently, several methods for assessing non-evoked pain in rodent models have been reported (Shimada and LaMotte, 2008; Langford et al., 2010; Navratilova and Porreca, 2014). With these advancements in hand, we are now making significant progress toward the evaluation of pain and analgesia in the presence of craniofacial pathology.

TRPV1, a capsaicin receptor, is endogenously activated by oxidized lipids (Chung et al., 2011; Ruparel et al., 2012); TRPA1 is activated by natural compounds such as mustard oil, and by multiple endogenous electrophiles such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (Chung et al., 2011; Trevisan et al., 2014; Sugiyama et al., 2017). TRPV1 contributes to cutaneous thermal hyperalgesia, and TRPA1 contributes to cutaneous cold and mechanical hyperalgesia (Chung et al., 2011). However, the data regarding the roles of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in spontaneous pain produced by inflammation or injury of skin or joint are equivocal (Wu et al., 2008; Okun et al., 2011; Okun et al., 2012; Wei et al., 2012; Fernandes et al., 2016). TRPV1 and TRPA1 are expressed in muscle nociceptors, and contribute to mechanical hyperalgesia in response to external pressure following inflammation and eccentric contraction (Fujii et al., 2008; Ota et al., 2013; Asgar et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2016), which likely underpin pressure-evoked pain in humans. Recently, we showed that TRPV1 substantially contributes to spontaneous pain, but only marginally mediates bite-evoked pain in mice (Wang et al., 2017). These findings raised questions as to whether TRPA1 also contributes to spontaneous pain or bite-evoked pain in mice, and whether TRPV1 and TRPA1 act additively or redundantly.

In this study, we have used a mouse model of masseter inflammation to determine the effects of inhibition of TRPA1 alone or in combination with TRPV1 on spontaneous pain and bite-evoked pain. We used three different methods to evaluate non-evoked pain behaviors, and compared their applicability to craniofacial pain models. Our results provide insight into molecular mechanisms of craniofacial muscle pain, especially non-evoked spontaneous pain, which may lead to improved strategies to manage acute or chronic muscle pain conditions. Our findings also suggest methodological considerations that may improve evaluation of pain and analgesia in preclinical craniofacial pain models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals

A total of 330 mice were used in this study. All procedures were conducted under a University of Maryland approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Adult male C57BL/6 mice, TRPV1 knockout (KO) mice (C57BL/6 background), TRPA1 KO mice (mixed B6;129 background), and their littermate wildtype mice were used as indicated in Results. TRPV1 KO and TRPA1 KO mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. For experiments in which facial grimace and wiping behaviors were assessed, 8 to 12 week-old mice were used. For all experiments involving bite force measurements, 12 to 16 week-old mice were used. All animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room under a 12:12 light–dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum.

Drugs

Complete Freund adjuvant (CFA; Sigma) was emulsified in an equal volume of isotonic saline. AP18 (40 nmol/μl; Sigma), a TRPA1 antagonist, was dissolved in PBS containing 1% DMSO and 10% Tween-80. AMG 9810 (10 nmol/μl; Sigma), a TRPV1 antagonist, was dissolved in PBS containing 5% DMSO and 10% Tween-80. Antibodies against 13(S)-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (HODE) and 9(S)-HODE (Oxford Biomedical Research; 1 mg/ml) or goat IgG (a negative control; Sigma; 1 mg/ml) were suspended in PBS. The specificity of these antibodies was previously validated (Spindler et al., 1996). Catalase (Sigma; bovine liver; 300 units in 20 μl) was dissolved in PBS. Heat-inactivated catalase (denatured by boiling for 10 min) was used as a control. The concentration and dose of catalase was determined previously (Trevisan et al., 2014). For intramuscular injection, mice were briefly anesthetized using 3% isoflurane.

Measurement of mouse grimace scale (MGS)

We measured MGS according to methods described previously (Wang et al., 2017). Each mouse was placed in a cubicle with four transparent Plexiglas walls, and was videotaped for 30 min for each experimental time point. To capture facial images of mice in an unbiased manner, image extraction was performed by blinded experimenters. Images containing a clear view of the entire face were manually captured every 3 min during the video recording (10 images per 30 min session). For consistency in assessing MGS, one experimenter scored all the images in a blinded manner. Five facial action units (AUs) were scored: orbital tightening, nose bulge, cheek bulge, ear position, and whisker change. Each AU was scored 0, 1, or 2 based on criteria described previously (Langford et al., 2010). A score of “0” represented absence of the AU, a score of “2” indicated obvious detection of the AU. A score of “1” was assigned when the scorer was not highly confident that the AU was present or absent, or when the AU exhibited a moderate appearance.

Measurement of face wiping behaviors

After the facial grimace scale video recording, the same groups of mice were used for measuring wiping behaviors as described previously (Wang et al., 2017). Each mouse was placed in a plastic container and video recorded for 30 min. Wiping behaviors were analyzed as described previously (Shimada and LaMotte, 2008). We defined the wiping behavior as a motion of the ipsilateral forelimb that begins at the back of the masseter muscle in front of the ear and moves forward in one direction from caudal to rostral. The experimenter was blinded to the experimental groups.

Conditioned place preference (CPP) assay

The CPP apparatus consists of a rectangular chamber with one side compartment measuring 23 cm × 26 cm with white walls showing vertical black stripes and grids on the floor, a central compartment measuring 23 cm × 11 cm with clear plexiglass walls and a plexiglass floor, and another side compartment measuring 23 cm × 26 cm with white walls showing horizontal black stripes and a mesh metal floor. All conditioning compartments were maintained at the same overall level of brightness. On the day before CFA injection (Day 1), each mouse had access to all chambers for 15 minutes. The behaviors of mice were videotaped, and the time spent in each chamber was determined. Mice that showed a preconditioning place preference bias, assessed as time spent in any one side chamber more than 12 minutes or less than 3 minutes during this test period, were excluded from further experiments. On Day 2, CFA was injected to the left masseter muscle, and after 6 hours mice were placed in the CPP apparatus with access to all compartments. On the conditioning day (Day 3), mice underwent conditioning with alternate treatment-chamber pairings. Mice received administration of saline to the ipsilateral masseter muscle, and were placed immediately in a randomly chosen side chamber for 30 minutes with no access to the other chamber. Vehicle or one of the antagonists (AMG9810, AP18, or combination of AMG9810 and AP18) was injected into the masseter muscle (ipsilateral or contralateral) 4 hours after saline injection, and the mice were placed in the other side chamber for 30 minutes. Chamber pairings were counterbalanced. On the test day (Day 4), mice were placed in the middle chamber with free access to all chambers, and their movements were recorded over a 15 min period with a video camera. Time spent in each of the chambers was determined and analyzed offline. Increased time spent in a chamber was scored as indicating preference for that chamber.

Bite force assay in mice

To assess bite-evoked pain associated with craniofacial muscle inflammation in mice, we measured changes in bite force as described previously (Wang et al., 2017). Bite force was measured using a bite force transducer consisting of two parallel aluminum plates connected to a force-displacement transducer (FT03; Grass instruments). Bite force was recorded for 120 seconds per session and the top five force measurements were averaged. The experimenter was blinded to the experimental groups.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Normality of distribution of data was assessed by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The data exhibited normal distribution with equal variance, and parametric analyses were carried out. Comparisons between more than two groups with different time points were performed using two-way repeated measure ANOVA with Bonferroni post tests unless otherwise indicated. The criterion for statistical significance was P<0.05. Data analysis was performed using Graphpad 5 (La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

TRPA1 contributes to spontaneous pain during masseter muscle inflammation in mice

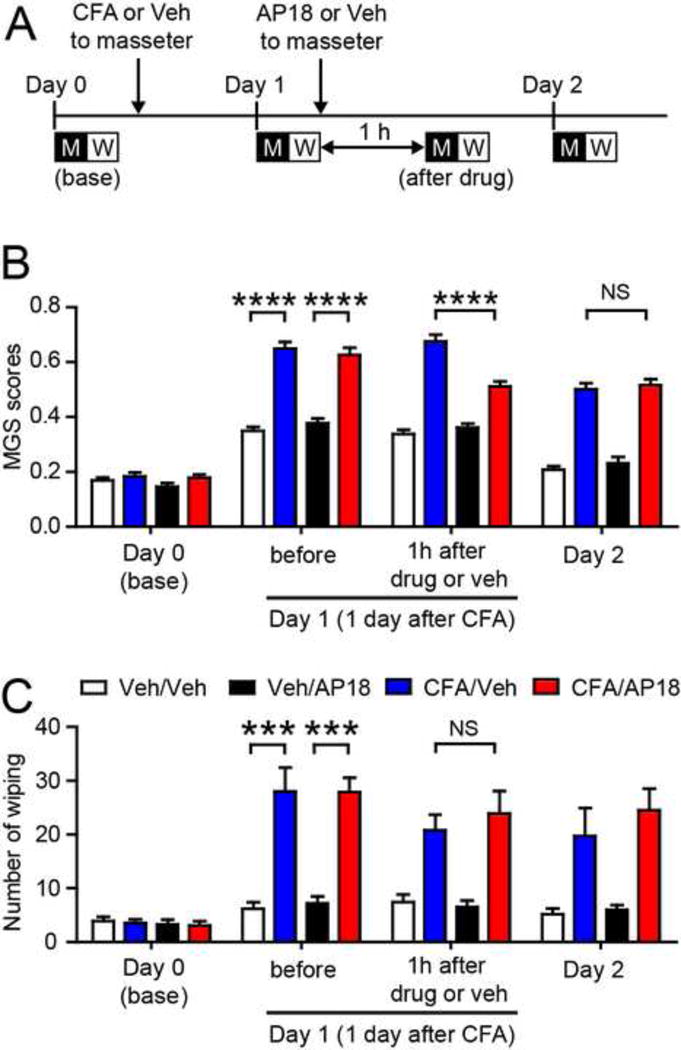

To produce masseter inflammation, CFA was injected into masseter muscle. Pain-associated behaviors were evaluated before CFA injection and after 1 day and 2 days following CFA injection. In another group of mice, saline (vehicle) was injected into masseter muscle as a control (Fig. 1A). Masseter injection of CFA significantly increased mouse grimace scale (MGS) scores and face wiping behaviors compared to the saline-injected group on day 1 (Fig. 1B, 1C; MGS, F3,36=44.00, p<0.0001; wiping, F3,36=25.41, p<0.0001). This result is consistent with our previous finding (Wang et al., 2017). To determine the involvement of TRPA1, we administered AP18, a specific antagonist of TRPA1, or vehicle into the ipsilateral masseter muscle 1 day after CFA injection. MGS scores were evaluated before and 1 hour after injection of AP18 or vehicle. Because MGS scores and wiping behavior were measured in the same animals, the exact time point of recording wiping behavior was actually 1.5 hours after AP18 administration. For simplicity, we refer to this time point as 1 hour for both MGS scores and wiping behavior in Results (Fig. 1A). Administration of AP18 but not vehicle significantly suppressed the increase in MGS following CFA injection (Fig. 1B; F3,36=12.74, p<0.0001). This effect of AP18 was reversible, and the inhibitory effect was not observed when MGS was assessed 24 h after CFA injection. AP18, however, did not significantly affect face wiping (Fig. 1C; F3,36=2.00, p=0.13). We also tested the dose- and temporal-dependency of AP18 inhibition of MGS (Fig. 2A). Administration of AP18 on either day 1 or day 2 following masseter injection of CFA inhibited MGS (Fig. 2B; F4,32=18.47, p<0.0001). The inhibitory effect of AP18 was dose-dependent. Masseter injection of low dose of AP18 (100 nmol) did not significantly inhibit MGS 1 or 2 days after CFA; administration of 300 nmol AP18 produced an intermediate, albeit significant, level of inhibition of MGS 1 day after CFA, but did not produce significant inhibition 2 days after CFA. In contrast, administration of 800 nmol of AP18 produced significant inhibition of MGS both 1 and 2 days after CFA (Fig. 2B). To further determine the role of TRPA1, we tested the effect of genetic knockout (KO) of TRPA1 on masseter pain. We found that the increase in MGS following CFA injection was significantly less in TRPA1 KO mice than littermate wildtype (WT) control mice (Fig. 3A; F1,22=35.69, p<0.0001). Face wiping behavior in TRPA1 KO was also less than in WT but did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3B; F1,22=1.48, p=0.23). These data suggest that TRPA1 is a mediator of spontaneous pain from masseter inflammation, and indicate that evaluation by MGS provides a more sensitive measure of spontaneous pain from masseter inflammation than face wiping.

Figure 1. Effects of pharmacological inhibition of TRPA1 on MGS and face wiping behaviors during masseter inflammation in mice.

A. Time line of mouse grimace scale (MGS) and wiping experiment. Day 0 is the time when baseline behaviors were measured and CFA (20 μl) or vehicle (saline) was injected to one side of masseter muscle. M, 30 min video recording session of MGS; W, 30 min video recording session of face wiping.

B-C. Averaged mouse grimace scale (MGS) scores (B) and number of face wiping behaviors (C) following time course indicated in panel A. AP18 (TRPA1 antagonist; 800 nmol in 20 μl) or vehicle was injected into the ipsilateral masseter muscle 1 day after CFA injection. MGS and wiping behaviors were measured before and 1 h after drug or vehicle injection. ****p<0.0001; NS, not significant; Bonferroni post-hoc test following two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. Mean±SEM. N=10 in each group.

Figure 2. Dose-dependent inhibition MGS scores by TRPA1 inhibitor on different days during masseter inflammation in mice.

A. Time line of MGS assay. M, 30 min video recording session of MGS.

B. Effects AP18 on MGS. Masseter muscle was injected with AP18 (three different doses) 1 day after CFA (day 1) and 2 days after CFA (day 2). MGS was assayed 1 h after drug or vehicle injection. **p<0.01; ****p<0.0001; Bonferroni post-hoc test following two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. Mean±SEM. N=5 in each group.

Fig. 3. Effects of genetic knockout of TRPA1 on MGS and face wiping behaviors during masseter inflammation in mice.

MGS scores (A) and face wiping behaviors (B) following unilateral masseter injection of CFA in TRPA1 knockout (KO) or littermate wildtype (WT) mice. ****p<0.0001; NS, not significant; Bonferroni post-hoc test following two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. Mean±SEM. N=12 in each group.

We postulated that endogenous ligands that cause constitutive activation of TRPA1 leading to spontaneous pain might be generated within the muscle tissue during inflammation. TRPA1 is activated by multiple products from oxidative stress including H2O2 (Andersson et al., 2008). Scavenging H2O2 by peripheral injection of catalase, an H2O2-detoxifying enzyme, attenuates inflammatory hyperalgesia (Trevisan et al., 2014), and direct injection of H2O2 produces muscle pain by activation of TRPA1 (Sugiyama et al., 2017). To test the effects of scavenging H2O2 at the site of masseter inflammation, catalase was injected into masseter muscle 1 day after CFA injection. Heat-inactivated catalase was injected in control animals. MGS was evaluated before and 1 hour after the injection of catalase. Injection of active catalase significantly reduced MGS scores during masseter inflammation compared to injection of the inactivated catalase control (Fig. 4A; F9,80=11.49; p<0.0001). Neither active nor inactive catalase affected MGS scores in mice that had received saline control rather than CFA in masseter muscle. Based on these analgesic effects of scavenging TRPA1 ligands, in conjunction with our previous finding that inhibition of TRPV1 also suppressed MGS during masseter inflammation (Wang et al., 2017), we postulated that scavenging putative ligands of TRPV1 might produce a similar analgesic effect. To test this, we evaluated the effects of depleting putative endogenous ligands of TRPV1. Oxidized linoleic acid metabolites (OLAMs) such as 9(S)-HODE or 13(S)-HODE have been suggested to be endogenous ligands (agonists) or positive modulators of TRPV1 (Ruparel et al., 2012). Depletion of OLAMs by specific antibodies attenuated inflammatory hyperalgesia (Ruparel et al., 2012; Alsalem et al., 2013). We depleted OLAMs by injecting antibodies against 9(S)-HODE and 13(S)-HODE into masseter muscle 1 day after the injection of CFA or vehicle. In vehicle-injected uninflamed control mice, depletion of OLAMS did not alter MGS scores. However, in CFA-injected mice, depletion of OLAMs significantly attenuated MGS scores after 1 hour (Fig. 4B; F9,80=10.94; p<0.0001). Injection of control IgG did not affect MGS scores in either inflamed or uninflamed mice. These data suggest that spontaneous pain is mediated by TRPV1 and TRPA1 following their activation by putative endogenous ligands generated in inflamed muscle.

Fig. 4. Effects of depletion of hydrogen peroxide or oxidized linoleic acid metabolites in masseter muscle on MGS during masseter inflammation.

A. Catalase (300 units in 20 μl PBS; H2O2 detoxifying enzyme) or control (heat-inactivated catalase) was injected into ipsilateral masseter muscle 1 day after unilateral masseter injection of CFA or vehicle. Effects on MGS scores were measured 1 h after drug injection. *p<0.05; Bonferroni post-hoc test following two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. N=6 in each group.

B. A mixture of antibodies against 9(S)-HODE and 13(S)-HODE (10 μg each in 20 μl PBS) or goat IgG (20 μg in 20 μl PBS) were injected into ipsilateral masseter muscle 1 day after unilateral masseter injection of saline or CFA. Effects on MGS scores were evaluated 1 h after drug injection. **p<0.01; Bonferroni post-hoc test following two-Way ANOVA with repeated measures. N=6 in each group.

Simultaneous inhibition of TRPV1 and TRPA1 showed different extent of additive effects in different assays

Pharmacological or genetic inhibition of TRPA1 partially inhibited MGS scores but did not affect face wiping during masseter inflammation (Fig. 1 and 3). In comparison, inhibition of TRPV1 partially attenuated both MGS and face wiping under the same conditions (Wang et al., 2017). Therefore, we examined the possibility that the combination of TRPV1 and TRPA1 antagonists would produce additive or synergistic analgesic effects. Indeed, an additive inhibitory effect of simultaneous pharmacological inhibition of TRPV1 and TRPA1 has been reported in an experimental colitis model (Vermeulen et al., 2013). In our study, simultaneous administration of AMG and AP18 into masseter muscle 1 day after masseter injection of CFA significantly attenuated MGS (Fig. 5A; F6,56=7.16; p<0.0001), but the extent of inhibition was comparable to that achieved by AP18 (Fig. 1A) or AMG alone (Wang et al., 2017). The combination of AMG and AP18 also significantly attenuated face wiping (Fig. 5B; Time effect, F2,56=76.45, p<0.0001; Group effect F3,28=1.59, p=0.21; CFA/Veh/ipsi vs CFA/AMG+AP18/ipsi, p<0.05 in Bonferroni post-hoc test). Since face wiping was not inhibited by AP18 alone (Fig. 1C) but was attenuated by AMG9810 (Wang et al., 2017), inhibition of face wiping by the combination treatment in Fig. 5B is likely a consequence of TRPV1 inhibition. When the combination of AMG9810 and AP18 was applied to the contralateral masseter muscle, neither MGS nor face wiping was suppressed (Fig. 5A, B), suggesting that these drugs work locally.

Fig. 5. Effects of simultaneous pharmacological inhibition of TRPV1 and TRPA1 on MGS and wiping behaviors during masseter inflammation in mice.

CFA was injected into the masseter muscle on day 0. Drugs or vehicle were injected into the ipsilateral (ipsi) or contralateral (contra) masseter muscle on day 1 (1 day after CFA). MGS scores (A) and numbers of face wiping (B) were evaluated 1 h (MGS) or 1.5 h (face wiping) after drug injection. AP18 (TRPA1 antagonist; 800 nmol in 20 μl) and AMG9810 (AMG, TRPV1 antagonist; 200 nmol in 20 μl) were injected simultaneously. *p<0.05; ****p<0.0001; Bonferroni post-hoc test following two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. N=10 in CFA/Veh/ipsi and CFA/AMG+AP18/ipsi; n=6 in CFA/Veh/contra and CFA/AMG+AP18/contra.

The lack of additive effects of the combination of TRPV1 and TRPA1 antagonists might result from potential functional dependencies between the two molecules such that inhibition of any one of the molecules produces the same effects as inhibiting both. Since genetic inhibition of TRPV1 affects both MGS and face wiping (Wang et al., 2017), we tested whether pharmacological inhibition of TRPA1 produced additional attenuation of spontaneous pain when TRPV1 was not expressed. Masseter injection of AP18 in TRPV1 KO mice after 1 day following masseter injection of CFA significantly attenuated MGS scores compared to vehicle injection (Fig. 6A; F2,36=24.68, p<0.0001). As well, masseter injection of AP18 in TRPV1 KO mice also significantly inhibited face wiping behaviors (Fig. 6B; F2,36=5.53, p<0.01). We also determined the effects of pharmacological inhibition of TRPV1 in the absence of TRPA1 expression by injecting AMG in TRPA1 KO mice. Masseter injection of AMG in TRPA1 KO mice 1 day after masseter injection of CFA significantly attenuated MGS compared to vehicle injection (Fig. 6C; F2,34=12.24, p<0.0001). In contrast, masseter injection of AMG in TRPA1 KO mice did not significantly affect face wiping behaviors (Fig. 6D). These data suggest that genetic knockout of TRPV1 influences the effects of pharmacological inhibition of TRPA1 and that genetic knockout of TRPA1 influences the effects of pharmacological inhibition of TRPV1 in vivo. This suggests that variation in pain and pain-associated behaviors may be influenced by intricate interactions between TRPV1 and TRPA1 as previously suggested (Weng et al., 2015).

Fig. 6. Effects of combined pharmacological and genetic inhibition of TRPA1 and TRPV1 on MGS and wiping behaviors.

CFA was injected unilaterally into masseter muscle on day 0. Drugs or vehicle were injected into the ipsilateral masseter muscle on day 1 (one day after CFA). AP18 was injected to ipsilateral masseter muscle in TRPV1 KO mice (A, B). AMG was injected to ipsilateral masseter muscle in TRPA1 KO mice (C, D). MGS scores (A, C) and numbers of face wiping (B, D) were evaluated 1 h (MGS) or 1.5 h (face wiping) after drug injection. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001; Bonferroni post-hoc test following two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. N=10 in each group.

To further assess the roles of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in non-evoked ongoing pain during muscle inflammation, we performed the CPP test. To test analgesic effects of TRPV1 or TRPA1 inhibition at muscle afferent terminals after CFA, we conditioned mice to TRPV1 or TRPA1 antagonists alone or in combination injected directly into the muscles according to the time line shown in Figure 7A. In preconditioning, we confirmed that no mouse showed a preference for either of the two chambers. When mice were conditioned with vehicle, no CPP was observed (Fig. 7B). When mice were conditioned with either masseter injection of AMG9810 or AP18 alone, we observed significant CPP to the chamber paired with the antagonist (Fig. 7C and 7D; AMG9810, F2,40=15.68, p<0.0001; AP18, F2,36=19.78, p<0.0001). When mice were conditioned with a combination of TRPV1 and TRPA1 antagonists, CPP to the drugs was much more robust (Fig. 7E; F2,40=53.31, p<0.0001). The injection of AMG9810 plus AP18 to contralateral masseter muscle did not induce CPP (Fig. 7F). Comparison of difference scores (increased time spent in the drug-paired chamber) showed a significant increase in CPP when mice were conditioned with a combination of the antagonists (Fig. 7G; One-way ANOVA, F4,47=12.68, p<0.0001). These additive effects of AMG9810 and AP18 observed in the CPP assay contrasts with the lack of additive effects observed in MGS or face wiping assay (Fig. 5).

Fig. 7. Effects of pharmacological inhibition of TRPV1 and TRPA1 on conditioned place preference (CPP) during masseter inflammation.

A. Time line of CPP experiment.

B-F. Time spent in saline- or drug-paired chambers were compared at baseline (Day 1), before conditioning (Day 2; 6 hours after unilateral injection of CFA), and after conditioning (Day 4). Mice were conditioned with vehicle (B; n=10 in each group), AMG9810 (C; n=11 in each group), AP18 (D; n=10 in each group), or AMG9810+AP18 (E; n=11 in each group) by injection of the drug into the ipsilateral masseter muscle. One group (F) was conditioned with AMG+AP18 by injection of the drugs into the contralateral masseter muscle. N=10 in each group. ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; Bonferroni post hoc test following two-way ANOVA with repeated measures.

G. Difference scores calculated as increased time spent in the drug-paired chamber on test day compared to the day before conditioning. Increased time indicates increased preference for the drug treatment. *p<0.05; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; Bonferroni post hoc test following one-way ANOVA.

TRPV1 and TRPA1 are not major contributors to bite-evoked muscle pain

In addition to spontaneous ongoing pain, pain-evoked by muscle function is a major symptom of muscle inflammation. We previously suggested that TRPV1 plays only a marginal effect on bite-evoked pain during masseter inflammation (Wang et al., 2017). Here, we performed the bite force assay to determine if TRPA1 contributed to bite-evoked pain. Consistent with our previous findings (Wang et al., 2017), CFA injections to bilateral masseter muscles resulted in significantly reduced bite force. The maximum bite force reduction occurred 1 day after CFA injection, and bite force gradually recovered toward baseline over 3 days. Bilateral injections of AP18 (800 nmol/side, a dose that significantly inhibited MGS scores; Fig 1) 1 day after CFA injection did not affect the bite force (Fig. 8A). TRPA1 KO mice exhibited a reduction in bite force following CFA injection to an extent comparable to that of WT mice (Fig. 8B). We also found that a simultaneous injection of AMG and AP18 to masseter muscle did not affect the bite force (n=3, not shown). We then tested whether pre-emptive administration of AP18 or AMG9810 affected development of bite-evoked pain following CFA injection. To reduce the rate of development of bite-evoked pain, which might better reveal a weak contribution of TRPV1 or TRPA1, we injected only 10 μl CFA in this experiment. The effects of antagonists on bite-evoked pain were then assessed 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h after CFA injection. We found no effect of AP18 or AMG9810 alone or in combination on CFA-induced changes in bite force compared to the vehicle injection (Fig. 8C). These data suggest that simultaneous pharmacological inhibition of TRPV1 and TRPA1 do not affect bite-evoked pain during masseter inflammation.

Fig. 8. TRPA1 does not contribute to bite-evoked pain during masseter inflammation.

A. Effects of AP18 (800 nmol/side) or vehicle injected bilaterally into the masseter muscles 1 day after bilateral CFA injections. NS, not significant. N=11 in AP18 and 7 in Veh.

B. Bite force of TRPV1 KO or WT mice measured before and 1 day after bilateral injections of CFA (20 μl) into the masseter muscles. N=9 in WT and 10 in TRPA1 KO.

C. Bilateral injection of drugs or vehicle into the masseter muscles 30 min prior to bilateral injections of CFA (10 μl per side). Bite force was measured 1, 2, and 4 hours after CFA injections, and was normalized to the baseline bite force of each animal. N=8 in Veh, 9 in AMG, 6 in AP18 and 7 in AMG+AP18.

DISCUSSION

In a previous study, we established assays of MGS and face wiping to measure non-evoked pain in mice with masseter inflammation (Wang et al., 2017). We showed that increases in MGS scores were attenuated following chemical ablation or chemogenetic silencing of TRPV1-expressing afferents, suggesting that these behavioral outcomes were mediated by nociception. In the current study, we have established that CPP can be used as an additional measure of ongoing pain in mice with masseter inflammation. Our data showed that inhibition of TRPA1 attenuated MGS scores and increased CPP during masseter inflammation. These results, along with results in our previous study (Wang et al., 2017), suggest that TRPV1 and TRPA1 contribute to non-evoked spontaneous pain during masseter inflammation in mice. Since administration of TRPA1/TRPV1 antagonists to the contralateral masseter did not affect MGS or CPP, we conclude that the attenuation of spontaneous pain by the antagonist must result from local inhibition of TRPA1/TRPV1 rather than from systemic effects. Consistently, scavenging OLAMs or H2O2 in inflamed masseter muscle attenuated MGS scores, suggesting that generation of putative endogenous ligands of TRPV1 or TRPA1 at the site of inflammation might cause constitutive activation of these channels leading to spontaneous pain. Prolonged low level chemical activation of TRPV1 is known to induce non-desensitizing firing of nociceptors similar to spontaneous firing (Wu et al., 2013). Likewise, generation of reactive oxygen species, which are endogenous agonists of TRPA1, at the site of nerve injury contributes to face wiping behavior following infraorbital nerve injury (Trevisan et al., 2016). Since masseter inflammation is known to result in upregulation of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in trigeminal ganglia (Asgar et al., 2015; Chung et al., 2016), it is likely that the increased spontaneous pain observed here is partly mediated by increased expression of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in nociceptors.

Simultaneous inhibition of TRPV1 and TRPA1 produced clear additive inhibitory effects on CPP. Such additive effects suggest a potential therapeutic benefit of co-administration of TRPV1 and TRPA1 antagonists in treating muscle pain. Our findings are reminiscent of the additive inhibitory effects of TRPV1 and TRPA1 antagonists on visceral hypersensitivity (Vermeulen et al., 2013). TRPV1 or TRPA1 antagonists alone partially inhibit visceral hypersensitivity, and combined peripheral administration of TRPV1 and TRPA1 antagonists shows additive inhibitory effects on visceral hypersensitivity. Interestingly, intrathecal administration did not show additive effects in this model (Vermeulen et al., 2013). In the current study, whereas the effects of AP18 plus AMG on CPP were greater than the effects achieved by single antagonist, AP18 plus AMG did not produce clear additive effects on MGS. The source of this discrepancy between the two assays is not clear. We speculate that the dynamic range of the MGS assay as an outcome measure may be rather small, in part due to the fact that even vehicle injection produces significantly elevated MGS scores. While the MGS assay evaluates relatively immediate nocifensive responses during pain experience, CPP involves more complicated neurobiological processes. The CPP assay is a broad measure of processes pertaining to analgesic experience. CPP is associated with learning and memory driving reward–seeking behaviors by selecting chambers (Navratilova and Porreca, 2014). As the final readout is based on a binary process (chamber choice), the assay could potentially amplify small differences in the experienced pain level. These observations suggest that MGS may be more useful when determining direct effects of treatment on non-evoked pain, whereas CPP may be more sensitive (or useful) in assessing qualitative analgesic responses.

Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of TRPV1 commonly affected outcomes in the three methods we employed to assess non-evoked pain or analgesic effects in the presence of masseter inflammation. In contrast, the inhibition of TRPA1 affected MGS and CPP but did not clearly attenuate face wiping behaviors. Although the reason for this differential contribution is not clear, it is possible that face wiping behavior is evoked by greater nociceptive inputs than MGS or CPP, or that TRPA1-mediated nociception is not great enough to trigger face wiping behaviors. Formally, we cannot exclude the possibility that the difference is simply due to subject variability in the face wiping assay. However, a differential contribution of TRPA1 in a different spontaneous pain model has been reported previously. In knee joint arthritis, TRPA1 contributes to guarding behavior (Fernandes et al., 2016) but not to CPP (Okun et al., 2012), suggesting that the contribution of TRPA1 to spontaneous pain is context-dependent.

Although TRPA1 antagonist AP18 did not inhibit face wiping behavior in WT mice, AP18 produced small but significant inhibition of face wiping behaviors in TRPV1 KO mice. In contrast, TRPV1 antagonist did not inhibit face wiping behaviors in TRPA1 KO mice. Differential effects of TRPV1 and TRPA1 antagonists in WT versus TRPA1 or TRPV1 knockout mice suggest complex interactions between TRPV1 and TRPA1 may be involved in spontaneous pain from masseter inflammation. Activation of TRPV1 leads to desensitization of TRPA1 (Akopian et al., 2007). Activation of TRPA1 leads to desensitization (Jeske et al., 2006) or sensitization (Gees et al., 2013; Spahn et al., 2014) of TRPV1. TRPV1 constitutively suppresses the function of TRPA1 (Weng et al., 2015), but functional TRPA1 is reduced in TRPV1 KO sensory neurons (Salas et al., 2009). TRPV1 and TRPA1 are synergistically activated when both are activated at the same time in vagal afferents (Lee et al., 2015). The intricate interactions between TRPV1 and TRPA1 are mediated both by multiple signaling cascades and by heteromultimerization of TRPV1 and TRPA1 (Ruparel et al., 2008; Fischer et al., 2014; Spahn et al., 2014). A recent study suggested that TRPV1/TRPA1 interaction involves a regulatory protein TMEM100 (Weng et al., 2015), which is differentially regulated in trigeminal ganglia following masseter inflammation (Chung et al., 2016). It is possible that behavioral consequences of TRPV1/TRPA1 manipulation result from the complicated interactions of these two molecules. It will be important in future studies to delineate details of the molecular interactions of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in masseter afferents and their pathophysiological modulation during inflammation.

In contrast to the substantial contribution to spontaneous pain, the inhibition of TRPA1 alone or in combination with TRPV1 did not significantly alter bite-evoked pain. Since our previous study suggested that inputs from TRPV1-expressing afferents contribute to bite-evoked pain (Wang et al., 2017), we presume that as yet undetermined molecules in addition to TRPV1 and TRPA1 expressed in TRPV1-positive neurons contribute to bite-evoked pain. Transcriptomic analysis of trigeminal ganglia suggests that multiple genes are differentially regulated in TRPV1-lineage afferents during masseter inflammation (Chung et al., 2016). Alternatively, it is possible that inflammation-mediated regulation of trigeminal motor neurons overrides nociceptor-mediated regulation to such an extent that TRPV1/TRPA1 inhibition does not produce detectable reversal of inflammation-mediated reduction of bite force. Thus, it will be important in future studies to dissect the molecular and neural mechanisms of bite-evoked pain.

We conclude that TRPA1 contributes to spontaneous pain, but not to bite-evoked pain from masseter inflammation. We conclude that simultaneous suppression of TRPV1 and TRPA1 produces additional suppression of CPP but not MGS, face wiping, or bite-evoked pain. Results of this study suggest that combined targeting of TRPV1 and TRPA1 might be used to treat spontaneous muscle pain.

Inhibition of TRPA1 attenuated mouse grimace scale during muscle inflammation but not face wiping.

Scavenging putative ligands for TRPV1 or TRPA1 attenuated mouse grimace scale scores.

Simultaneous inhibition of TRPV1 and TRPA1 additively produced conditioned place preference.

Simultaneous inhibition of TRPV1 and TRPA1 did not affect bite-evoked pain.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Feng Wei for helping with the conditioned place preference assay, and Dr. Jin Y. Ro and John Joseph for helpful comments. We also thank Indi Jetton, Anthony Attala, Jessica Conway, and Cassie McIltrot for helping with video analysis. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 DE023846 (M.K.C). The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akopian AN, Ruparel NB, Jeske NA, Hargreaves KM. Transient receptor potential TRPA1 channel desensitization in sensory neurons is agonist dependent and regulated by TRPV1-directed internalization. J Physiol. 2007;583:175–193. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.133231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsalem M, Wong A, Millns P, Arya PH, Chan MS, Bennett A, Barrett DA, Chapman V, et al. The contribution of the endogenous TRPV1 ligands 9-HODE and 13-HODE to nociceptive processing and their role in peripheral inflammatory pain mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:1961–1974. doi: 10.1111/bph.12092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson DA, Gentry C, Moss S, Bevan S. Transient receptor potential A1 is a sensory receptor for multiple products of oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2485–2494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5369-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgar J, Zhang Y, Saloman JL, Wang S, Chung MK, Ro JY. The role of TRPA1 in muscle pain and mechanical hypersensitivity under inflammatory conditions in rats. Neuroscience. 2015;310:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrillon EE, Cairns BE, Ernberg M, Wang K, Sessle BJ, Arendt-Nielsen L, Svensson P. Effect of peripheral NMDA receptor blockade with ketamine on chronic myofascial pain in temporomandibular disorder patients: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Orofac Pain. 2008;22:122–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MK, Jung SJ, Oh SB. Role of TRP Channels in Pain Sensation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;704:615–636. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MK, Park J, Asgar J, Ro JY. Transcriptome analysis of trigeminal ganglia following masseter muscle inflammation in rats. Mol Pain. 2016;12 doi: 10.1177/1744806916668526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson A. Experimental tooth clenching. A model for studying mechanisms of muscle pain. Swed Dent J Suppl. 2013:9–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes ES, Russell FA, Alawi KM, Sand C, Liang L, Salamon R, Bodkin JV, Aubdool AA, et al. Environmental cold exposure increases blood flow and affects pain sensitivity in the knee joints of CFA-induced arthritic mice in a TRPA1-dependent manner. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:7. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0905-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer MJ, Balasuriya D, Jeggle P, Goetze TA, McNaughton PA, Reeh PW, Edwardson JM. Direct evidence for functional TRPV1/TRPA1 heteromers. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:2229–2241. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1497-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii Y, Ozaki N, Taguchi T, Mizumura K, Furukawa K, Sugiura Y. TRP channels and ASICs mediate mechanical hyperalgesia in models of inflammatory muscle pain and delayed onset muscle soreness. Pain. 2008;140:292–304. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gees M, Alpizar YA, Boonen B, Sanchez A, Everaerts W, Segal A, Xue F, Janssens A, et al. Mechanisms of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 activation and sensitization by allyl isothiocyanate. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;84:325–334. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.085548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeske NA, Patwardhan AM, Gamper N, Price TJ, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. Cannabinoid WIN 55,212-2 egulates TRPV1 phosphorylation in sensory neurons. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32879–32890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603220200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford DJ, Bailey AL, Chanda ML, Clarke SE, Drummond TE, Echols S, Glick S, Ingrao J, et al. Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nat Methods. 2010;7:447–449. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee LY, Hsu CC, Lin YJ, Lin RL, Khosravi M. Interaction between TRPA1 and TRPV1: Synergy on pulmonary sensory nerves. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2015;35:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litcher-Kelly L, Martino SA, Broderick JE, Stone AA. A systematic review of measures used to assess chronic musculoskeletal pain in clinical and randomized controlled clinical trials. J Pain. 2007;8:906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel L. Submasseteric abscess caused by a dentigerous cyst mimicking a parotitis: report of two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:996–999. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navratilova E, Porreca F. Reward and motivation in pain and pain relief. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1304–1312. doi: 10.1038/nn.3811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun A, DeFelice M, Eyde N, Ren J, Mercado R, King T, Porreca F. Transient inflammation-induced ongoing pain is driven by TRPV1 sensitive afferents. Mol Pain. 2011;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun A, Liu P, Davis P, Ren J, Remeniuk B, Brion T, Ossipov MH, Xie J, et al. Afferent drive elicits ongoing pain in a model of advanced osteoarthritis. Pain. 2012;153:924–933. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota H, Katanosaka K, Murase S, Kashio M, Tominaga M, Mizumura K. TRPV1 and TRPV4 play pivotal roles in delayed onset muscle soreness. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks EL, Geha PY, Baliki MN, Katz J, Schnitzer TJ, Apkarian AV. Brain activity for chronic knee osteoarthritis: dissociating evoked pain from spontaneous pain. Eur J Pain. 2011;15:843 e841–814. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruparel NB, Patwardhan AM, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. Homologous and heterologous desensitization of capsaicin and mustard oil responses utilize different cellular pathways in nociceptors. Pain. 2008;135:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruparel S, Green D, Chen P, Hargreaves KM. The cytochrome P450 inhibitor, ketoconazole, inhibits oxidized linoleic acid metabolite-mediated peripheral inflammatory pain. Mol Pain. 2012;8:73. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas MM, Hargreaves KM, Akopian AN. TRPA1-mediated responses in trigeminal sensory neurons: interaction between TRPA1 and TRPV1. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:1568–1578. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada SG, LaMotte RH. Behavioral differentiation between itch and pain in mouse. Pain. 2008;139:681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spahn V, Stein C, Zollner C. Modulation of transient receptor vanilloid 1 activity by transient receptor potential ankyrin 1. Mol Pharmacol. 2014;85:335–344. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.088997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spindler SA, Clark KS, Callewaert DM, Reddy RG. Significance and immunoassay of 9- and 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:187–191. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama D, Kang S, Arpey N, Arunakul P, Usachev YM, Brennan TJ. Hydrogen Peroxide Induces Muscle Nociception via Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 Receptors. Anesthesiology. 2017;127:695–708. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevisan G, Benemei S, Materazzi S, De Logu F, De Siena G, Fusi C, Fortes Rossato M, Coppi E, et al. TRPA1 mediates trigeminal neuropathic pain in mice downstream of monocytes/macrophages and oxidative stress. Brain. 2016;139:1361–1377. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevisan G, Hoffmeister C, Rossato MF, Oliveira SM, Silva MA, Silva CR, Fusi C, Tonello R, et al. TRPA1 receptor stimulation by hydrogen peroxide is critical to trigger hyperalgesia and inflammation in a model of acute gout. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;72:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen W, De Man JG, De Schepper HU, Bult H, Moreels TG, Pelckmans PA, De Winter BY. Role of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in visceral hypersensitivity to colorectal distension during experimental colitis in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;698:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Lim J, Joseph J, Wei F, Ro JY, Chung MK. Spontaneous and Bite-Evoked Muscle Pain Are Mediated by a Common Nociceptive Pathway With Differential Contribution by TRPV1. J Pain. 2017;18:1333–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Karimaa M, Korjamo T, Koivisto A, Pertovaara A. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 ion channel contributes to guarding pain and mechanical hypersensitivity in a rat model of postoperative pain. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:137–148. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31825adb0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HJ, Patel KN, Jeske NA, Bierbower SM, Zou W, Tiwari V, Zheng Q, Tang Z, et al. Tmem100 Is a Regulator of TRPA1-TRPV1 Complex and Contributes to Persistent Pain. Neuron. 2015;85:833–846. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Gavva NR, Brennan TJ. Effect of AMG0347, a transient receptor potential type V1 receptor antagonist, and morphine on pain behavior after plantar incision. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:1100–1108. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31817302b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Yang Q, Crook RJ, O’Neil RG, Walters ET. TRPV1 channels make major contributions to behavioral hypersensitivity and spontaneous activity in nociceptors after spinal cord injury. Pain. 2013;154:2130–2141. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]