Abstract

Exercise has been proposed as a treatment for several psychiatric disorders. Exercise may act in part through beneficial effects on reward functioning, as it alters neurotransmitter levels in reward-related circuits. However, there has been little investigation of the effect of exercise on reward functions in humans. We hypothesized an acute bout of exercise would increase motivation for and pleasurable responses to rewards in healthy humans. In addition, we examined possible moderators of exercise’s effects, including demographics, fitness and previous exercise experience. Thirty-five participants completed exercise and sedentary control sessions in randomized, counterbalanced order on separate days. Immediately after each activity, participants completed measures of motivation for and pleasurable responses to rewards, consisting of willingness to exert effort for monetary rewards and subjective responses to emotional pictures. Exercise did not increase motivation or pleasurable responses on average. However, individuals who had been running for more years showed increases in motivation for rewards after exercise, while individuals with less years running showed decreases. Further, individuals with higher resting heart rate variability reported lower arousal in response to all emotional pictures after exercise, while individuals with low heart rate variability reported increased arousal in response to all emotional pictures after exercise. General fitness did not have similar moderating effects. In conclusion, acute exercise improved reward functioning only in individuals accustomed to that type of exercise. This suggests a possible conditioned effect of exercise on reward functioning. Previous experience with the exercise used should be examined as a possible moderator in exercise treatment trials.

Keywords: Reward functioning, exercise, motivation, pleasure, Effort Expenditure for Rewards Task, International Affective Picture System

1. Introduction

Exercise has been proposed as a treatment for several psychiatric illnesses, including depression, addiction and negative symptoms of schizophrenia [1–3]. Exercise is an appealing intervention due to a favorable side-effect profile and good acceptability to patients [3, 4]. However, although exercise shows some efficacy in psychiatric disorders [1–3], little is known about the mechanisms underlying its positive effects. An understanding of how exercise acts on psychiatric functioning will be critical to making it a more potent intervention.

One possible way that exercise may improve psychiatric symptoms is through beneficial effects on reward-related functioning. Deficits in reward-related functions such as motivation and enjoyment cut across psychiatric illnesses, including those for which exercise appears effective [5, 6]. Recent conceptualizations identify at least two major components of reward functioning: 1. Motivational reward, i.e. exertion of effort to gain rewards, controlled by striatal dopaminergic circuits [7]. Consummatory reward, i.e. pleasure when rewards are received, mediated by opioid “hotspots” in the striatum [8]; Although these functions are unlikely to be completely independent, they do appear to have at least partially separable neural bases [8]. There are plausible neurobiological reasons to expect exercise may positively affect both of these functions. First, preliminary animal studies suggest that exercise, both acute and chronic, increases dopaminergic activity in striatal circuits associated with reward [9–12]. In humans, exercise has been shown to increase the availability of striatal dopamine receptors among patients with Parkinson’s disease and methamphetamine use disorder [13, 14], although no exercise effect has also been reported in one study among healthy adults [15]. In theory, increases should increase motivation for rewards, just as pharmacological manipulations that increase dopaminergic levels improve motivation for rewards [16–18]. Second, positron emission tomography (PET) studies in humans suggest that acute bouts of exercise can result in opioid release in the brain (although extent of release may depend on the intensity of exercise and the training status of the participant) [19, 20]. This might be expected to increase liking for rewards in way similar to administration of opioid agonists [21–23].

However, there has been little investigation of the acute effect of exercise on reward-related functioning in humans. The studies that do exist have primarily investigated the effect of exercise on neural responses to palatable foods. These have produced mixed results, with both increases and decreases in activity in reward-related areas in response to foods after acute exercise [24–27]. Only one study has examined non-food reward. This study showed that acute exercise decreased brain responses in reward-related areas during anticipation of monetary reward, only in men who did not exercise regularly (no effect was seen in men who exercised often)[28]. This anticipatory phase is generally thought to reflect motivational or dopaminergic aspect of reward system functioning [29], so this result is inconsistent with the animal literature suggesting improved DAergic tone after exercise. There was also no significant effect of acute exercise on brain responses to reward feedback, which is primarily thought to reflect consummatory system functioning [29]. However, the behavioral implications of these fMRI findings are unclear, as the relationship between brain activation and actual motivation or subjective responses to rewards is often unmeasured or unknown.

Thus, the current study aimed to test the effect of an acute bout of exercise on behavioral and subjective measures of motivational and consummatory responses to rewards in healthy humans. Our measure of motivational reward functioning was the Effort Expenditure for Rewards Task (EEfRT), which measures the willingness of participants to exert physical effort (button pressing) for monetary rewards. The EEfRT was translated directly from animal tasks that are sensitive to DA manipulations, and has demonstrated sensitivity to DA alterations in healthy humans [16, 30]. Further, individual differences in striatal dopamine transmission, measured by positron emission tomography (PET), have been correlated with the willingness to expend greater effort for larger rewards in the EEfRT [30]. Our measure of consummatory reward was subjective ratings of positivity/negativity of emotional pictures from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS). This measure has face validity for consummatory reward, as participants simply respond subjectively to the presentation of positive stimuli (positive pictures), and has been sensitive to opioidergic manipulations in humans [21]. We carefully standardized the exercise dose, which has often not been well-controlled in previous studies, by having individuals complete two conditions: exercise above lactate threshold and rest. We were not able to directly measure levels of neurotransmitters in the current study, as there are no validated peripheral measures of neurotransmitter release, and PET scanning was not feasible for this initial trial. However, we selected lactate threshold as our threshold because this corresponds to the point at which plasma catecholamines, including epinephrine, norepinephrine and DA increase exponentially [31, 32]. Research conducted in laboratory animals suggests these peripheral increases coincide with increased catecholamines centrally [11]. Further, exercise at this threshold produces behavioral effects on other functions thought to be partly DA-dependent, such as speed of cognitive functioning [33]. Our hypotheses were that exercise would increase both motivational reward functioning, as indicated by greater willingness to exert effort for monetary rewards, and consummatory reward functioning, as indicated by more positive subjective responses to presentation of positive pictures. In addition, we examined on an exploratory basis possible moderators of the effect of exercise on reward functioning, including demographic variables, intensity of the individualized exercise dose, indicators of general fitness/previous exercise experience, and a physiological indicator of baseline positive emotional functioning/emotional flexibility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overall Design

The study consisted of a three session within-subject design comparing exercise and a sedentary control. All three sessions occurred in the same exercise testing room, and sessions were separated by at least two days but not more than twenty days. Experimental sessions were conducted between 6:00 and 11:00 am. Participants completed the two experimental sessions at the same time of the day, and were asked to consume the identical meal (if any) prior to each visit. Participants were asked to refrain from alcohol and strenuous exercise 24 hours prior to each visit, and to refrain from consuming caffeine for 4h prior to each visit. Participants who did not refrain (confirmed verbally) were rescheduled. Participants first completed an orientation session, at which they provided informed consent, practiced the reward functioning measures, and completed a lactate threshold test to determine their individual exercise prescription. Participants then completed two experimental sessions conducted in randomized, counterbalanced order. At the exercise session, participants ran on a treadmill at an intensity 5% above their individually determined lactate threshold for 20 minutes. At the control session, participants sat quietly for 20 minutes. Immediately after each activity, participants completed the EEfRT and IAPS measures of motivation and pleasure (see Measures). All sessions lasted approximately 1 hr. Institutional review boards at the University of Houston and at the University of Texas Health Science Center granted ethical approval for this study, and all procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Participants

Participants were 35 healthy adults (n = 18 female). The sample size was selected to detect an effect of moderate size or better (d = 0.53) with 80% power in our within-subjects design. Of note, previous research reports a large effect size (d = 0.72) of pharmacological manipulations on the EEfRT [16]. Inclusion criteria were: 1. Between ages 18 and 44; 2. Less than two cardiovascular risk factors on the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and American Heart Association (AHA) pre-exercise screening questionnaire [34]; 3. Reporting spending between 30 minutes to 3 hours in vigorous physical activity each week on a physical activity questionnaire; 4. Smoking less than 10 cigarettes per week. Participants were recruited via flyers and personal referrals. Interested participants were first sent the ACSM/AHA Pre-exercise Screening Questionnaire and a physical activity questionnaire by email, and informed about the exclusion criteria related to these measures. Participants who believed they would qualify for the study were invited to the laboratory to complete the orientation and lactate threshold test.

2.3. Orientation and Lactate Threshold Test

During this visit, participants first provided informed consent. They then completed the screening questionnaires, and measures of resting blood pressure, height and weight were taken. Anyone who did not satisfy inclusion criteria was excluded from further participation. Participants who met criteria then completed the blood lactate threshold test. During the test, participants wore a heart rate monitor (Polar V800, Polar, Kempele Finland) for the continuous measurement of heart rate. The test consisted of walking/running on a treadmill (Woodway Desmo, Woodway, Waukesha WI, USA) at a 2% incline in 3-minute stages. The treadmill speed began at 7km/hr, and was increased by 1km/hr every 3 minutes. Before exercise and between each 3-minute stage, participants briefly paused while a capillary blood sample was collected from their ear lobe. The lactate concentration in each blood sample was immediately measured using an automated pre-calibrated lactate analyzer (LactatePlus Meter, Nova Biomedical, Waltham MA, USA). The test ended when the concentration of lactate in the blood exceeded 4mmol, or when the participant chose to stop (whichever occurred first). Participants also indicated their rate of perceived exertion at the end of each stage on the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE; see Measures) [35] . The information provided by this test was used to determine the participants’ lactate threshold and calculate the speed for their experimental trial. The speed corresponding to lactate threshold was visually determined by plotting blood lactate (mmol/L) vs speed (km/h) according to the break point method [36]. Following completion of the lactate threshold test, participants were introduced to the two reward functioning measures, and completed practice trials of both.

2.4 Experimental Sessions

Once abstinence from exercise, alcohol, and caffeine had been confirmed, participants were fitted with a heart rate monitor, and completed their assigned task for that session, either running for 20 minutes or sitting quietly for 20 minutes. For the run, participants ran on the treadmill at a 2% incline at the speed corresponding to 5% above their lactate threshold, as determined during the orientation session. The speed of the treadmill was adjusted if required to elicit the expected heart rate (that is, heart rate corresponding to 5% above lactate threshold). This method has previously been shown in our lab to elicit the expected metabolic strain among non-elite athlete populations [37]. During the rest session, participants sat quietly in a chair facing the treadmill for 20 minutes. Heart rate and ratings of perceived exertion (Borg scale) were recorded during both sessions at five-minute intervals. Immediately after completing the run or rest, participants completed the EEfRT and IAPS measures of reward functioning (see Measures). At the end of the final session, participants were debriefed, and received their winnings from the EEfRT.

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. The Effort Expenditure for Rewards Task (EEfRT)

The EEfRT is a behavioral measure of reward-related decision-making [38]. In each trial, participants chose between two button-press tasks varying in difficulty and monetary reward. At the beginning of each trial, participants had 5 seconds to choose between the “easy task”, requiring 30 key presses with the dominant index finger in 7s, and the “hard task”, requiring 100 key presses with the non-dominant pinky finger in 21s. Participants were eligible to win $1.00 for successfully completing an easy task and were eligible to win between $1.24-$4.21 for completing a hard task. Participants were not guaranteed to win the monetary reward for completing a task; there were “win” trials, in which they could receive the stated reward, and “no win” trials, in which they would receive no money. Trials had a 12%, 50%, or 88% probability of being a win trial. At the beginning of each trial, the computer screen displayed the reward probability and amount to assist the participant in choosing. During the task, the computer displayed participant progress and time remaining to complete the task. After each task, the computer displayed completion and win amount feedback. Participants were informed the task would last 20 minutes, regardless of their choices. At the conclusion of each session, two of the participant’s “win” trials were randomly chosen for payout. Because participants will complete varying numbers of trials in 20 minutes, typically analysis of the EEfRT is restricted to the first 50 trials of the task. All participants completed at least 50 trials.

2.5.2. The International Affective Picture System Task (IAPS)

The IAPS task is a measure of subjective responses to emotional stimuli that uses a validated, standardized picture set to evoke emotional responses [39]. The IAPS pictures have been extensively validated with healthy college students. Normative ratings included with the IAPS manual were used to select positive, neutral and negative pictures [40]. At each session, participants viewed and rated 18 positive, 18 neutral and 18 negative pictures (categorized based on normative ratings). Pictures were presented full-screen and one at a time on a computer screen for 6s each. Each picture was immediately followed by visual analog scale ratings of valence (−4, very negative to 4, very positive 4) and arousal (0, completely unarousing to 9, completely arousing). A different set of pictures, matched on normative arousal and valence, was used at each session to avoid adaptation. Valence and arousal ratings of positive pictures were the primary outcomes. Negative and neutral pictures were included to rule out non-specific effects of exercise on all emotional stimuli.

2.5.3. Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE)

The Borg RPE is a widely used subjective measure of the level of exertion [35]. The participant is asked to rate their perception of exertion on a scale ranging from 6 (no exertion at all) to 20 (maximal exertion). This measure was used as one potential moderator indicating the intensity of the exercise session.

2.5.4. High-Frequency Heart Rate Variability (HF-HRV)

High-frequency heart-rate variability represents the extent of beat-to-beat variability in the heart period that occurs with respiration [41]. The inter-beat-interval between successive heartbeats was collected during the 20 minute rest session via the Polar V800 heart rate monitor. This data was only available from a subset of participants (n = 24, 11 female), because collection began some time after initiation of the study. After the first and last minute of data collection was discarded to exclude any possible movement artifacts from the beginning or ending of the rest session, a trained rater edited the resulting inter-beat intervals for irregular beats using CardioEdit software (Brain-Body Center, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago IL). HF-HRV was quantified from these inter-beat interval sequences using CardioBatch software (Brain-Body Center, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago IL) and the moving polynomial method (Porges, 1985; Porges & Bohrer, 1990), with standard adult HF-HRV settings: 2Hz sample rate, frequency window of 0.12-0.40Hz, and 30s epoch length. Baseline HF-HRV was collected and evaluated as a potential moderator due to suggestions that HF-HRV may capture individual differences in either hedonic capacity [42, 43], i.e. the ability to experience positive emotions, or emotional flexibility, i.e. the ability to flexibly adapt behavior and physiology to meet emotional challenges [44].

2.6. Statistical Analyses

2.6.1. The effect of exercise on motivational reward functioning

A binomial generalized linear mixed effects modeling (GLMM) with a logit link function was used examine the effect of exercise on willingness to exert physical effort. The dichotomous variable of effort choice (hard vs. easy) was modeled as a function of the fixed effects of Exercise Condition (run vs. rest), Reward Probability, Reward Amount, Trial Number and their interactions. If the participant did not make a choice within 5s the trial was marked as “no choice” and considered missing, which GLMM can accommodate straightforwardly. We established our random effects model by generating a maximal model and iteratively reducing it per Bates, Kliegl, Vasishth, and Baayen [45] using Likelihood ratio tests, changes in Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and principle component analyses.

2.6.2. The effect of exercise on consummatory reward functioning

Linear mixed effects modeling (LMM) with an identity link function was used examine the effect of exercise on subjective valence and arousal ratings of IAPS pictures. Subjective valence and arousal ratings were averaged across each Picture Type (negative, neutral, and positive). These continuous outcomes were each modeled as a function of the fixed effects of Exercise Condition (run vs. rest) and Picture Type (negative, neutral, and positive) and their interactions. To verify that the picture sets were balanced, we also included Picture Set (A vs. B) and the interaction between Picture Set and Picture Type as fixed effects. All variables were contrast coded, with the three-level variable of Picture Type represented using orthogonal polynomial contrasts capturing potential linear and quadratic trends. Consistent with the EEfRT analyses, we established our random effects model by generating a maximal model and iteratively reducing it per Bates, et al [45].

2.6.3. Moderators of the effect of exercise on reward functioning

We explored eight variables as possible moderators of the effect of exercise on reward functioning, in the following categories: demographic variables consisting of sex and age; measures of intensity of exercise consisting of average HR as a percent of age predicted maximum [46] and RPE score at the end of the exercise trial; measures of running fitness consisting of years as a runner and speed at lactate threshold; and a physiological indicator of baseline positive emotional functioning, resting heart rate variability (HRV). Categorical potential moderators were contrast coded and continuous ones mean centered prior to analysis. Each potential moderator was first screened for a likely moderating effect by introducing the main effect of the moderator and an interaction term with the Exercise into the fixed effects model for each task. For this initial screening, a simple random effects structure consisting of a random intercept for participant was used to speed evaluation. For screening models that indicated a moderator with significant interactions with Exercise, a maximal random effects model was developed and iteratively reduced per Bates et al. [45] to produce a final model.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

Descriptive statistics for key demographic variables and potential covariates are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| M(SD) or N(%) | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Sex (Female) | 18 (51%) |

| Age in Years | 24.9 (6.5) |

| Body Mass Index | 24.9 (3.1) |

| Intensity of Exercise Session | |

| Exercise Trial average HR as % of age predicted max | 88.8 (5.9) |

| Exercise Trial Borg RPE at end | 14.3 (2.3) |

| Running Fitness/Previous Experience | |

| Years as a runner | 5.9 (5.1) |

| Speed at lactate threshold in kph | 9.0 (1.47) |

| Resting Heart Rate Variability in ln(ms2) | 6.8 (0.8)^ |

HR = Heart Rate; RPE = Rating of Percieved Exertion; kph = kilometers per hour

available in 24 participants only

3.2. Motivational Reward – EEfRT Task

One participant selected all hard tasks for one session, resulting in outlier data. This participant was excluded from all analyses involving the EEfRT, yielding a final n of 34 for EEfRT analyses. The final model’s random effect structure consisted of a random intercept for Participant and random slopes for Reward Amount, Probability (linear and quadratic trends), and the interaction of Reward Amount and Probability (linear trend). Inclusion of correlations between these random effects produced a failure to converge, indicating this model was too complex to be supported by the data, thus correlations were excluded. Results of this GLMM are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Generalized Linear Mixed Model for Hard Task Choices on the EEfRT

| Fixed Effects | B | SE (B) | Sig. (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.84 | 0.27 | 0.002* |

| Exercise | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Probability (Linear Trend) | 6.15 | 0.55 | <0.001* |

| Probability (Quadratic Trend) | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| Reward Amount | 1.73 | 0.17 | <0.001* |

| Trial Number | −0.04 | 0.004 | <0.001* |

| Exercise × Probability (Linear) | −0.21 | 0.38 | 0.56 |

| Exercise × Probability (Quadratic) | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.68 |

| Exercise × Amount | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.33 |

| Exercise × Trial Number | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.95 |

| Probability (Linear) × Amount | 1.78 | 0.38 | <0.001* |

| Probability (Quadratic) × Amount | −0.41 | 0.17 | 0.02* |

| Exercise × Probability (Linear) × Amount | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.25 |

| Exercise × Probability (Quadratic) × Amount | −0.13 | 0.30 | 0.68 |

|

| |||

| Random Effects | SD | ||

|

| |||

| Subject Intercept | 1.47 | ||

| Probability (Linear) Subj | 2.67 | ||

| Probability (Quadratic) Subj | 0.80 | ||

| Reward Amount Subj | 0.78 | ||

| Probability (Linear) × Reward Amount Subj | 1.47 | ||

p < 0.05

As can be seen in Table 2, exercise did not significantly affect the number of hard tasks selected on the EEfRT. A typical effect of probability was seen, with participants selecting more hard tasks under higher probabilities of winning. A typical effect of reward was also present, with participants selecting more hard choices when the reward was worth more. There was also an expected interaction between probability and amount reflecting that these variables jointly determine the expected value of a given hard task choice. Exercise did not interact with any of these effects of probability or amount. Last, there was a typical effect of Trial Number, with decreased selection of the hard task on later trials, possibly reflecting physical fatigue across trials. Exercise also did not interact with Trial Number, suggesting that an immediately previous bout of physical effort did not significantly affect the rate of physical fatigue on the EEfRT. In summary, on average we did not see a significant effect of exercise on motivational reward, despite expected effects of probability and reward indicating our participants were appropriately sensitive to other manipulations that increase or decrease motivation on this task.

We screened our eight potential covariates for interactions with the effect of exercise on hard task choice (as described in Statistical Analyses). Years as a runner significantly interacted with the effects of exercise on hard task choices. Therefore we constructed a final model with a full random effects structure to examine the moderating effect of years as a runner on the effect of exercise on hard task choices. The final model’s random effect structure consisted of a random intercept for Participant and random slopes for Reward Amount, Probability (linear and quadratic trends), and the interaction of Reward Amount and Probability (linear trend). Inclusion of correlations between these random effects was not indicated. Results of this GLMM are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Generalized Linear Mixed Model for Hard Task Choices on the EEfRT, including Years as a Runner as a moderator

| Fixed Effects | B | SE (B) | Sig. (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.84 | 0.27 | 0.002* |

| Exercise | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.09 |

| Probability (Linear Trend) | 6.17 | 0.55 | <0.001* |

| Probability (Quadratic Trend) | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| Reward Amount | 1.74 | 0.17 | <0.001* |

| Trial Number | −0.04 | 0.004 | <0.001* |

| Years as a Runner | 0.003 | 0.05 | 0.96 |

| Exercise × Years as a Runner | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02* |

| Exercise × Probability (Linear) | −0.20 | 0.38 | 0.60 |

| Exercise × Probability (Quadratic) | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.71 |

| Exercise × Amount | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.31 |

| Exercise × Trial Number | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.92 |

| Probability (Linear) × Amount | 1.78 | 0.38 | <0.001* |

| Probability (Quadratic) × Amount | −0.41 | 0.17 | 0.02* |

| Exercise × Probability (Linear) × Amount | 0.54 | 0.43 | 0.22 |

| Exercise × Probability (Quadratic) × Amount | −0.14 | 0.30 | 0.65 |

|

| |||

| Random Effects | SD | ||

|

| |||

| Subject Intercept | 1.47 | ||

| Probability (Linear) Subj | 2.67 | ||

| Probability (Quadratic) Subj | 0.80 | ||

| Reward Amount Subj | 0.79 | ||

| Probability (Linear) × Reward Amount Subj | 1.47 | ||

p < 0.05

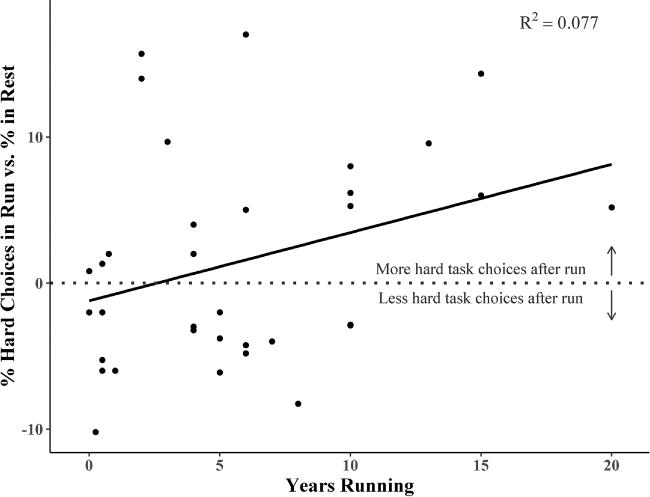

As can be seen in Table 3, there was a significant positive relationship between years as a runner and the effects of exercise on hard task choices. Further investigation of this relationship showed that exercise produced decreases in effort for individuals with fewer years as a runner, while for those with more years as a runner, exercise produced increases in effort (see Fig. 1.).

Figure 1. Years Running moderates the effect of exercise on motivation for reward.

Difference scores representing percent hard task choices on the EEfRT in the Run vs. Rest exercise conditions were computed for each participant, to represent the effect of exercise on motivation for reward for each participant. A simple linear regression was conducted with Years Running as the predictor and percent hard task choice difference scores as the outcome to illustrate the interaction detected in the linear mixed model.

3.3. Consummatory Reward – IAPS Task

The final model for valence ratings had a random effect structure consisting of a random intercept for Participant, and a random slope for the linear effect of Picture Type. Inclusion of correlations between these random effects was not indicated. Results of the Valence Ratings LMM are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Linear Mixed Model for Valence Ratings on the IAPS

| Fixed Effects | B | SE (B) | Sig. (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.05* |

| Exercise | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.53 |

| Picture Type (Linear Trend) | 3.74 | 0.18 | <0.001* |

| Picture Type (Quadratic Trend) | 0.50 | 0.05 | <0.001* |

| Picture Set | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| Exercise × Picture Type (Linear) | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.56 |

| Exercise × Picture Type (Quadratic) | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.57 |

| Picture Type (Linear) × Picture Set | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.70 |

| Picture Type (Quadratic) × Picture Set | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.56 |

|

| |||

| Random Effects | SD | ||

|

| |||

| Subject Intercept | 0.39 | ||

| Probability (Linear) Subj | 1.00 | ||

p < 0.05

As can be seen in Table 4, exercise did not significantly affect subjective ratings of valence for the IAPS pictures. A typical effect of picture type was seen, with participants rating positive pictures more positively than neutral pictures, and neutral pictures more positively than negative pictures, but exercise also did not interact with picture type. The lack of significant effects for picture set or interaction between picture set and picture type indicates we were successful in choosing sets that did not differ significantly in valence ratings. We screened our eight potential covariates for interactions with the effect of exercise on valence ratings (as described in Statistical Analyses), but no significant interactions were detected.

The final model for arousal ratings had a random effect structure consisting of a random intercept for Participant, and random slopes for the linear effect of Picture Type and the effect of Picture Set. Inclusion of correlations between these random effects was indicated. Results of the Arousal Ratings LMM are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Linear Mixed Model for Arousal Ratings on the IAPS

| Fixed Effects | B | SE (B) | Sig. (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.13 | 0.22 | <0.001* |

| Exercise | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.81 |

| Picture Type (Linear Trend) | −0.33 | 0.21 | 0.14 |

| Picture Type (Quadratic Trend) | −1.57 | 0.10 | <0.001* |

| Picture Set | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.90 |

| Exercise × Picture Type (Linear) | −0.01 | 0.24 | 0.98 |

| Exercise × Picture Type (Quadratic) | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.80 |

| Picture Type (Linear) × Picture Set | −0.17 | 0.24 | 0.46 |

| Picture Type (Quadratic) × Picture Set | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.21 |

|

| |||

| Random Effects | SD | Correlations

|

|

| Subj. | Pic. Type | ||

|

| |||

| Subject Intercept | 1.28 | ||

| Picture Type (Linear) Subj | 1.06 | <0.001 | |

| Picture Set Subj | 0.57 | −0.15 | 0.84 |

| Valence (Positive) Subj | |||

p < 0.05

As can be seen in Table 5, exercise did not significantly affect subjective ratings of arousal for the IAPS pictures. A typical effect of picture type was seen, with participants rating both positive and negative pictures as more arousing than neutral pictures, but exercise also did not interact with picture type. The lack of significant effects for picture set or interaction between picture set and picture type indicates we were successful in choosing sets that did not differ significantly in arousal ratings.

We screened our eight potential covariates for interactions with the effect of exercise on arousal ratings (as described in Statistical Analyses). HRV significantly interacted with the effect of exercise on arousal ratings in this screening model. Therefore we constructed a final model with a full random effects structure to examine the moderating effect of resting HRV on the effect of exercise on arousal ratings. This final model had a random effect structure consisting of a random intercept for Participant, and a random slope for the linear effect of Picture Type. Inclusion of correlations between these random effects was not indicated. This final model is reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Linear Mixed Model for Arousal Ratings on the IAPS, including baseline Heart Rate Variability as a moderator

| Fixed Effects | B | SE (B) | Sig. (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.94 | 0.28 | <0.001* |

| Exercise | −0.03 | 0.13 | 0.82 |

| Picture Type (Linear Trend) | −0.24 | 0.24 | 0.33 |

| Picture Type (Quadratic Trend) | −1.51 | 0.14 | <0.001* |

| Picture Set | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.19 |

| Baseline Heart Rate Variability | 0.16 | 0.34 | 0.65 |

| Exercise × Baseline Heart Rate Variability | −0.51 | 0.16 | 0.002* |

| Exercise × Picture Type (Linear) | 0.14 | 0.32 | 0.66 |

| Exercise × Picture Type (Quadratic) | 0.03 | 0.28 | 0.91 |

| Picture Type (Linear) × Picture Set | −0.21 | 0.32 | 0.53 |

| Picture Type (Quadratic) × Picture Set | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.33 |

|

| |||

| Random Effects | SD | ||

|

| |||

| Subject Intercept | 1.31 | ||

| Picture Type (Linear) Subj | 0.85 | ||

p < 0.05

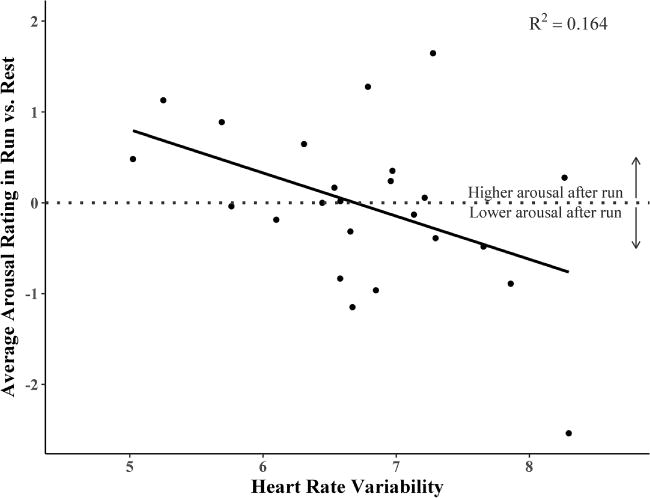

As can be seen in Table 6, there was a significant negative relationship between baseline heart rate variability and the effects of exercise on arousal. Further investigation of this relationship showed that exercise produced increases in arousal ratings across all pictures for individuals low in baseline heart rate variability, while for those high in baseline heart rate variability, exercise produced decreases (Fig. 2.).

Figure 2. Resting Heart Rate Variability moderates the effect of exercise condition on arousal responses to emotional pictures.

Difference scores representing average arousal ratings in the Run vs. Rest exercise conditions were computed for each participant, to represent the effect of exercise on arousal responses to the pictures for each participant. A simple linear regression was conducted with HRV as the predictor and arousal difference scores as the outcome to illustrate the interaction detected in the linear mixed model.

4. Discussion

Contrary to our predictions, we did not detect an effect of a bout of dynamic exercise above lactate threshold on measures of either motivational or consummatory reward. This was despite pre-clinical studies suggesting exercise above lactate threshold results in significant central catecholamine release, and demonstrated positive effects of exercise on other DA dependent behavioral measures such as cognitive functioning [33, 47]. However, our behavioral results are theoretically consistent with prior PET findings in humans suggesting both opioidergic and dopaminergic release in response to exercise is not robust on an average or group level. This includes prior studies of opiodergic release that found key moderating factors such as level of training [19, 20], and the sole PET study examining DA release after an acute bout of exercise in healthy adults, which concluded that the average DA release, if any, was too small to be detected by PET [15]. However, also broadly consistent with these previous studies, our exploratory analyses suggested that baseline characteristics may have important moderating influences on the effect of exercise on emotional functioning.

First, we found that previous experience with the selected exercise moderated the effect of exercise on motivational reward functioning. For participants with more experience running, running exercise tended to increase motivational reward functioning, consistent with our initial hypotheses that DA release due to exercise would increase the willingness to exert effort for rewards. However, for participants with less experience running, running exercise tended to decrease willingness to exert effort for reward. This did not appear to simply reflect better overall fitness, as we did not see the same effect for our other indicators of overall fitness or difficulty of the exercise session. This suggests a possible conditioned effect of exercise on reward functioning that depends on past experience with the same exercise stimulus. To an extent this is consistent with previous research indicating acute exercise decreased brain responses in reward-related areas during anticipation of monetary reward in men who did not exercise regularly, while no effect was seen in men who exercised often [28]. However, in that study the participant’s regular exercise was not necessarily of the same type performed in the study. In conclusion, our results strongly suggest that prior experience with the selected type of exercise should be examined as a possible moderating variable in clinical studies of exercise treatment.

Second, we found that individuals with lower baseline HRV, which has often been interpreted as a measure of either hedonic capacity [42, 43], i.e. the ability to experience positive emotions, or emotional flexibility, i.e. the ability to flexibly adapt behavior and physiology to meet emotional challenges [44], were more likely to perceive emotional stimuli as more arousing after exercise. In contrast, individuals with high HRV tended to perceive emotional stimuli as less arousing after exercise. Because this finding was not specific to positive emotional stimuli it is difficult to interpret this effect as having to do with consummatory reward or hedonic capacity. One alternate interpretation is that for individuals with low HRV, the challenge of a moderate exercise stressor dysregulated emotion, creating more intense reactions (arousal) to both positive and negative stimuli. In contrast, those with high HRV may be better able to flexibly emotionally adapt to a moderate exercise stressor, or may even experience a calming effect of exercise. Of note, although HRV does increase with fitness [48, 49], we did not see a relationship of HRV with our other indicators of general fitness or difficulty of the exercise task. It is likely that we did not see a relationship between HRV and fitness because our participants were of relatively similar training status (self-report a minimum of 30 minutes and a maximum of 3 hours of vigorous physical activity a week). Importantly, the lack of correlation between HRV and exercise measures suggest that the exercise bout was not easier for individuals with higher HRV.

It is important to keep in mind that our study examined a healthy adult sample engaging in a single acute bout of exercise. Thus, this may not model the effects of exercise on reward functioning when used as a chronic intervention in healthy or in clinical populations. However, it is notable that other treatments for depression (e.g. anti-depressants) do show acute actions in healthy adults that are thought to be related to their clinical effectiveness [50]. Unlike earlier studies that have examined the effect of exercise on reward pathways using more direct measures of brain functioning, such as fMRI, or neurotransmitter release, such as PET [13–15], we utilized behavioral measures thought to index underlying neural circuits. Use of behavioral tasks increases interpretability and reduces cost relative to imaging, but may have reduced our ability to detect an effect. It will be interesting for future studies to examine similar behavioral measures as those described here in combination with neuroimaging measures. For example, whether the results of Robertson et al [13], of increased striatal dopamine receptor availability among exercise-trained methamphetamine use disorder patients, translates to changes in motivational or consummatory reward behavior remains to be determined.

Another important consideration is that we did not attempt to utilize a “placebo” exercise condition (e.g. stretching), but rather had participants sit quietly. This could have introduced demand characteristics, as participants were not blind to condition and may have altered their behavior to fit pre-conceived notions about the effect of exercise, although the general expectation would be that these would increase rather than decrease the differences between our treatment conditions. Further, cognitive improvements following acute exercise have been found to be independent of expectation-driven placebo effects [51]. We also did not include positive controls, raising the possibility that the absence of exercise effects reflects a lack of sensitivity of our measures of motivational and consummatory reward. However, we and others have previously demonstrated differences in EEfRT and IAPS outcomes following dopaminergic and opioidergic manipulations among similarly healthy adult populations [16, 21, 30]. Finally, our analyses of potential moderators must be considered strictly exploratory and in need of replication, given the comparatively small sample size (particularly for HRV), and the number of potential moderators tested (eight) without correction for Type I error. Future studies ought also to consider whether exercise intensity or the timing of the behavioral measures impacts behavioral outcomes. One meta-analysis has demonstrated a positive relationship between exercise intensity and post-exercise increase in cognitive performance [47]. Whether exercise intensity would impact motivational or consummatory reward in healthy or clinical populations remains to be seen. The largest positive effects of acute exercise on cognition have been reported around 11-20 minutes post-exercise [47]. As completion of the EEfRT and IAPS instruments required approximately 40 minutes, beginning these measures immediately post-exercise meant subjects were engaged in the measures during the previously reported peak for cognitive tests. It is possible however that greater effects of exercise on our behavioral measures would be observed following a recovery period.

5. Conclusions

Contrary to our predictions, we did not see a robust, average effect of exercise on either motivational or consummatory reward functioning. Our exploratory analysis did reveal potential moderators of the effects of exercise, including experience with the specific exercise used for the intervention. This suggests either that exercise may operate strongly on reward functioning in a subset of patients only, or that exercise’s beneficial effects in psychiatric disorders are not related to effects on reward functioning. Future clinical studies should examine the effect of prior experience with the particular exercise chosen for the intervention as a possible moderator of exercise’s clinical effects.

Highlights.

Exercise is used as a psychiatric treatment, but its mechanism of action is unknown

Preclinical studies suggest exercise could positively affect reward functioning

We tested the effect of an acute exercise bout on responses to rewards in humans

Exercise only improved reward functioning in individuals accustomed to that exercise

Previous exercise experience should be examined as a moderator in exercise treatments

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number K08DA040006 to MCW].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Firth J, Cotter J, Elliott R, French P, Yung AR. A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. Psychol Med. 2015;45:1343–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714003110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linke SE, Ussher M. Exercise-based treatments for substance use disorders: evidence, theory, and practicality. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2014;41:7–15. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2014.976708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, Kampert JB, Clark CG, Chambliss HO. Exercise treatment for depression: Efficacy and dose response. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitton AE, Treadway MT, Pizzagalli DA. Reward processing dysfunction in major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2015;28:7–12. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garfield JBB, Lubman DI, Yücel M. Anhedonia in substance use disorders: A systematic review of its nature, course and clinical correlates. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;48:36–51. doi: 10.1177/0004867413508455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grace AA. The tonic/phasic model of dopamine system regulation and its implications for understanding alcohol and psychostimulant craving. Addiction. 2000;95:119–28. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berridge KC, Robinson TE, Aldridge JW. Dissecting components of reward: ‘liking’, ‘wanting’, and learning. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2009;9:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenwood BN, Foley TE, Le TV, Strong PV, Loughridge AB, Day HEW, et al. Long-term voluntary wheel running is rewarding and produces plasticity in the mesolimbic reward pathway. Behav Brain Res. 2011;217:354–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMorris T. Re-appraisal of the acute, moderate intensity exercise-catecholamines interaction effect on speed of cognition: role of the vagal/NTS afferent pathway. J Appl Physiol. 2015 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00749.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meeusen R, Fontenelle V. The Monoaminergic System in Animal Models of Exercise. In: Boecker H, Hillman CH, Scheef L, Strüder HK, editors. Functional Neuroimaging in Exercise and Sport Sciences. Springer; New York: 2012. pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meeusen R, De Meirleir K. Exercise and Brain Neurotransmission. Sports Med. 1995;20:160–88. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199520030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson CL, Ishibashi K, Chudzynski J, Mooney LJ, Rawson RA, Dolezal BA, et al. Effect of Exercise Training on Striatal Dopamine D2/D3 Receptors in Methamphetamine Users during Behavioral Treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015 doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher BE, Li Q, Nacca A, Salem GJ, Song J, Yip J, et al. Treadmill exercise elevates striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding potential in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. Neuroreport. 2013;24:509–14. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328361dc13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Franceschi D, Logan J, Pappas NR, et al. PET studies of the effects of aerobic exercise on human striatal dopamine release. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1352–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wardle MC, Treadway MT, Mayo LM, Zald DH, de Wit H. Amping up effort: Effects of d-amphetamine on human effort-based decision-making. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:16597–602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4387-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leyton M, Aan het Rot M, Booij L, Baker GB, Young SN, Benkelfat C. Mood-elevating effects of d-amphetamine and incentive salience: The effect of acute dopamine precursor depletion. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:129–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Floresco SB, Tse MT, Ghods-Sharifi S. Dopaminergic and glutamatergic regulation of effort- and delay-based decision making. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1966–79. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boecker H, Sprenger T, Spilker ME, Henriksen G, Koppenhoefer M, Wagner KJ, et al. The Runner’s High: Opioidergic Mechanisms in the Human Brain. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:2523–31. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saanijoki T, Tuominen L, Tuulari JJ, Nummenmaa L, Arponen E, Kalliokoski K, et al. Opioid Release after High-Intensity Interval Training in Healthy Human Subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017 doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gospic K, Gunnarsson T, Fransson P, Ingvar M, Lindefors N, Petrovic P. Emotional perception modulated by an opioid and a cholecystokinin agonist. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:295–307. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chelnokova O, Laeng B, Eikemo M, Riegels J, Loseth G, Maurud H, et al. Rewards of beauty: the opioid system mediates social motivation in humans. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:746–7. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castro DC, Berridge KC. Opioid hedonic hotspot in nucleus accumbens shell: mu, delta, and kappa maps for enhancement of sweetness “liking” and “wanting”. J Neurosci. 2014;34:4239–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4458-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crabtree DR, Chambers ES, Hardwick RM, Blannin AK. The effects of high-intensity exercise on neural responses to images of food. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014;99:258–67. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.071381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masterson TD, Kirwan CB, Davidson LE, Larson MJ, Keller KL, Fearnbach SN, et al. Brain reactivity to visual food stimuli after moderate-intensity exercise in children. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s11682-017-9766-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cornier MA, Melanson EL, Salzberg AK, Bechtell JL, Tregellas JR. The effects of exercise on the neuronal response to food cues. Physiol Behav. 2012;105:1028–34. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanlon B, Larson MJ, Bailey BW, LeCheminant JD. Neural response to pictures of food after exercise in normal-weight and obese women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:1864–70. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31825cade5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bothe N, Zschucke E, Dimeo F, Heinz A, Wustenberg T, Strohle A. Acute exercise influences reward processing in highly trained and untrained men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:583–91. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318275306f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knutson B, Fong GW, Adams CM, Varner JL, Hommer D. Dissociation of reward anticipation and outcome with event-related fMRI. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3683–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Treadway MT, Buckholtz JW, Cowan RL, Woodward ND, Li R, Ansari MS, et al. Dopaminergic mechanisms of individual differences in human effort-based decision-making. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:6170–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6459-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Podolin DA, Munger PA, Mazzeo RS. Plasma catecholamine and lactate response during graded exercise with varied glycogen conditions. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:1427–33. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.4.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winter B, Breitenstein C, Mooren FC, Voelker K, Fobker M, Lechtermann A, et al. High impact running improves learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;87:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMorris T, Hale BJ. Is there an acute exercise-induced physiological/biochemical threshold which triggers increased speed of cognitive functioning? A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2015;4:4–13. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balady GJ, Chaitman B, Driscoll D, Foster C, Froelicher E, Gordon N, et al. Recommendations for Cardiovascular Screening, Staffing, and Emergency Policies at Health/Fitness Facilities. Circulation. 1998;97:2283–93. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.22.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borg G. Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1970;2:92–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weltman A. The blood lactate response to exercise. Human Kinetics Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37.LaVoy EC, Hussain M, Reed J, Kunz H, Pistillo M, Bigley AB, et al. T-cell redeployment and intracellular cytokine expression following exercise: effects of exercise intensity and cytomegalovirus infection. Physiological Reports. 2017;5 doi: 10.14814/phy2.13070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Treadway MT, Buckholtz JW, Schwartzman AN, Lambert WE. Worth the ‘EEfRT’? The effort expenditure for rewards task as an objective measure of motivation and anhedonia. PloS one. 2009;4:e6598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lang PJ, Greenwald MK, Bradley MM, Hamm AO. Looking at pictures: Affective, facial, visceral, and behavioral reactions. Psychophysiology. 1993;30:261–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1993.tb03352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN, International affective picture system (IAPS) Technical manual and affective ratings. Gainesville, FL: NIMH Center for the study of emotion and attention, University of Florida; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berntson GG, Bigger JT, Jr, Eckberg DL, Grossman P, Kaufmann PG, Malik M, et al. Heart rate variability: Origins, methods, and interpretive caveats. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:623–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oveis C, Cohen AB, Gruber J, Shiota MN, Haidt J, Keltner D. Resting respiratory sinus arrhythmia is associated with tonic positive emotionality. Emotion. 2009;9:265–70. doi: 10.1037/a0015383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garland. Deficits in autonomic indices of emotion regulation and reward processing associated with prescription opioid use misuse. Psychopharmacology (Berlin, Germany) 2017;234:621. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4494-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balzarotti S, Biassoni F, Colombo B, Ciceri MR. Cardiac vagal control as a marker of emotion regulation in healthy adults: A review. Biol Psychol. 2017;130:54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bates D, Kliegl R, Vasishth S, Baayen H. Parsimonious mixed models. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2015 1506.04967. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka H, Monahan KD, Seals DR. Age-predicted maximal heart rate revisited. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:153–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chang YK, Labban JD, Gapin JI, Etnier JL. The effects of acute exercise on cognitive performance: A meta-analysis. Brain Res. 2012;1453:87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaikkonen KM, Korpelainen RI, Tulppo MP, Kaikkonen HS, Vanhala ML, Kallio MA, et al. Physical activity and aerobic fitness are positively associated with heart rate variability in obese adults. Journal of physical activity & health. 2014;11:1614–21. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rennie KL, Hemingway H, Kumari M, Brunner E, Malik M, Marmot M. Effects of moderate and vigorous physical activity on heart rate variability in a British study of civil servants. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:135–43. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harmer CJ, Goodwin GM, Cowen PJ. Why do antidepressants take so long to work? A cognitive neuropsychological model of antidepressant drug action. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195:102–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.051193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oberste M, Hartig P, Bloch W, Elsner B, Predel HG, Ernst B, et al. Control Group Paradigms in Studies Investigating Acute Effects of Exercise on Cognitive Performance–An Experiment on Expectation-Driven Placebo Effects. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2017:11. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]