Abstract

Background and objectives

All randomized trials of direct oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation excluded patients with severe kidney disease. The safety and effectiveness of direct oral anticoagulants across the range of eGFR in real-world settings is unknown. Our objective is to quantify the risk of bleeding and benefit of ischemic stroke prevention for direct oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation with and without CKD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

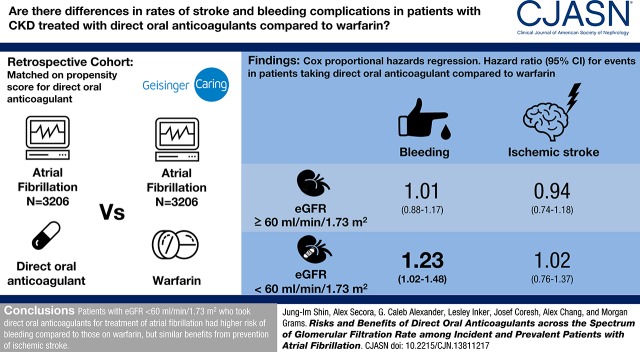

We created a propensity score–matched cohort of 3206 patients with atrial fibrillation and direct oral anticoagulant use and 3206 patients with atrial fibrillation using warfarin from October of 2010 to February of 2017 in an electronic health record (Geisinger Health System). The risks of bleeding and ischemic stroke were compared between direct oral anticoagulant and warfarin users using Cox proportional hazards regression, stratified by eGFR (≥60 and <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2).

Results

The mean (SD) age of the 6412 participants was 72 (12) years, 47% were women, and average eGFR was 69 (21) ml/min per 1.73 m2. There were 1181 bleeding events and 466 ischemic strokes over 7391 person-years of follow-up. Compared with warfarin use, the hazard ratios (HRs) (95% confidence interval [95% CI]) of bleeding associated with direct oral anticoagulant use were 1.01 (0.88 to 1.17) and 1.23 (1.02 to 1.48) for those with eGFR≥60 and eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively (P-interaction=0.10). There was no difference between direct oral anticoagulant and warfarin users in the risk of ischemic stroke: HRs (95% CI) of 0.94 (0.74 to 1.18) and 1.02 (0.76 to 1.37) for those with eGFR≥60 and eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively (P-interaction=0.70). Similar findings were observed with individual drugs.

Conclusions

In a large health care system, patients with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 who took direct oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation had slightly higher risk of bleeding compared with those on warfarin, but similar benefits from prevention of ischemic stroke.

Keywords: Anticoagulants; Atrial Fibrillation; Brain Ischemia; chronic kidney disease; Confidence Intervals; Direct Oral Anticoagulants; Electronic Health Records; Female; Follow-up Studies; glomerular filtration rate; Hemorrhage; Humans; kidney; Propensity Score; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Risk Assessment; Stroke; Warfarin

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation, the most common type of heart arrhythmia, increases a person’s risk of ischemic stroke; thus, oral anticoagulant therapy is recommended to reduce the risk (1,2). Until 2009, warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, was the most commonly used anticoagulant. Although warfarin is effective in preventing ischemic stroke (3), it also increases the risk of bleeding, ranging from minor to fatal hemorrhage (4). Moreover, warfarin use is limited by a narrow therapeutic index which requires frequent monitoring, resulting in substantial burden to patients (5,6).

Several direct oral anticoagulants, including direct thrombin inhibitors (e.g., dabigatran) and direct factor Xa inhibitors (e.g., rivaroxaban and apixaban), became available over the last decade as alternatives to warfarin. They offer potential advantages over warfarin, including rapid onset and offset of action, fewer drug and food interactions, and predictable anticoagulant effects without the need for frequent monitoring. Clinical trials reported that direct oral anticoagulants have similar or greater efficacy and safety in relation to warfarin in general atrial fibrillation populations (7–9).

All of the direct oral anticoagulants undergo kidney clearance to varying degrees. As a result, elimination of direct oral anticoagulants is slower in patients with CKD, which may predispose patients to drug accumulation and a greater risk of bleeding events (10). All randomized trials of direct oral anticoagulants for treatment of atrial fibrillation excluded patients with severe kidney disease (creatinine clearance <25–30 ml/min) (7–9). Despite the exclusion of such patients, direct oral anticoagulants have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in patients with severe kidney disease (i.e., dabigatran and rivaroxaban for creatinine clearance 15–30 ml/min and apixaban for creatinine clearance <15 ml/min). Given that 25% of patients with atrial fibrillation have CKD (11), the real-world safety and effectiveness of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation across the spectrum of GFR is of great public health importance.

Using a large, tertiary health system, we investigated the prevalence of direct oral anticoagulant use in patients with atrial fibrillation by eGFR category and used propensity score–matching techniques to evaluate the risk of bleeding and benefit of ischemic stroke prevention for direct oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin within categories of eGFR.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

We identified 20,727 patients with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, on the basis of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code 427.31, 427.32, or 427.3, who filled at least one prescription for anticoagulants and had a serum creatinine measured between October 19, 2010 (United States dabigatran approval date) and February 2, 2017 in the Geisinger Health System. Geisinger is a fully integrated rural health care system that serves a stable patient population (1% annual outmigration rate) with more than 3 million residents throughout 45 counties in central and northeastern Pennsylvania.

Exposure and Baseline Covariates

The primary exposure was direct oral anticoagulant use, ascertained from prescriptions. Warfarin use was considered an active comparator. A gap in prescriptions <60 days was not considered a medication discontinuation to allow for the possibility of stockpiling of medications.

A priori–selected covariates included in the propensity score model comprised factors potentially associated with treatment selection and/or outcomes, including demographics, eGFR, prescription year, history/duration of previous warfarin use, number of prior hospitalizations, comorbidities, and medication use (Table 1). The CHA2DS2–VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, stroke/transient ischemic attack/thromboembolism, vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, sex category) score (12) and the HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal kidney/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio, elderly [age ≥65 years], drugs/alcohol concomitantly) score (13), which predict the risk of stroke and bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation, were also included in the propensity score model.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in propensity score–matched patients with atrial fibrillation using direct oral anticoagulants or warfarin from October of 2010 to February of 2017 in the Geisinger Health System

| Variable | Direct Oral Anticoagulants (n=3206) | Warfarin (n=3206) | Standardized Mean Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), yr | 73 (11) | 72 (12) | 0.02 |

| Female, % | 47 | 46 | 0.01 |

| White, % | 98 | 98 | 0.01 |

| Mean eGFR (SD), ml/min per 1.73 m2a | 69 (21) | 68 (22) | 0.01 |

| eGFR category, % | |||

| ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 65 | 65 | 0.01 |

| 30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 31 | 31 | 0.000 |

| <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 4 | 4 | 0.01 |

| Year, % | |||

| 2010–2012 | 22 | 22 | 0.001 |

| 2013–2014 | 35 | 34 | 0.02 |

| 2015–2017 | 43 | 44 | 0.02 |

| Type of direct oral anticoagulant, % | |||

| Dabigatran | 27 | — | — |

| Rivaroxaban | 41 | — | — |

| Apixaban | 32 | — | — |

| History of prior anticoagulation, % | 37 | 37 | 0.01 |

| Median duration of prior anticoagulation (IQR), yrb | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–6) | 0.03 |

| Mean CHA2DS2–VASc score (SD) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 0.01 |

| Mean HAS-BLED score (SD) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.02 |

| Number of prior hospitalizations, % | |||

| None | 33 | 34 | 0.03 |

| 1–3 | 36 | 37 | 0.02 |

| 4–7 | 19 | 17 | 0.06 |

| ≥8 | 12 | 12 | 0.003 |

| Comorbidities, % | |||

| Hypertension | 83 | 83 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes | 34 | 34 | 0.01 |

| Congestive heart failure | 31 | 31 | 0.01 |

| Valvular heart disease | 24 | 26 | 0.03 |

| Valvular atrial fibrillationc | 4 | 5 | 0.04 |

| Myocardial infarction | 15 | 15 | 0.01 |

| Coronary artery disease | 41 | 41 | 0.01 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 16 | 16 | 0.01 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 10 | 10 | 0.004 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 5 | 5 | 0.01 |

| Bleeding | 35 | 35 | 0.004 |

| Anemia | 37 | 37 | 0.002 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 13 | 14 | 0.01 |

| Ischemic stroke | 9 | 9 | 0.01 |

| ESKD | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.02 |

| Medication use, % | |||

| NSAIDs | 24 | 24 | 0.01 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 22 | 23 | 0.03 |

| Statins | 32 | 31 | 0.001 |

| RAS blockers | 30 | 30 | 0.02 |

All P values are >0.05. —, not applicable; IQR, interquartile range; CHA2DS2–VASc, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes mellitus, stroke/transient ischemic attack/thromboembolism, vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, sex category; HAS-BLED, hypertension, abnormal kidney/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile international normalized ratio, elderly [age ≥65 years], drugs/alcohol concomitantly; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; RAS blockers, renin-angiotensin system blockers.

Median time (IQR) between eGFR measurements and initial dosing of direct oral anticoagulant was 2 d (0–45).

Only among those with a history of prior anticoagulation.

Valvular atrial fibrillation was defined as atrial fibrillation with rheumatic mitral stenosis or prosthetic heart valve.

eGFR was estimated from the serum creatinine measured (outpatient or inpatient) within 1 year before the baseline prescription date or up to 90 days after baseline, using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration Equation (14). eGFR was categorized into three groups (≥60, 30–59, and <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2) according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guideline and CKD was defined as eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (15). Baseline year was categorized into three groups (2010–2012, 2013–2014, and 2015–2017). Prior hospitalizations was categorized as none, 1–3, 4–7, and ≥8. Comorbid conditions were identified by the presence of relevant ICD-9-CM codes at any time before baseline (Supplemental Table 1). History of anemia was defined as blood hemoglobin <11 g/dl at any time before baseline. ESKD was identified by linkage to the United States Renal Data System. Baseline use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelet drugs, statins, and renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers was captured from prescription data within 90 days before inclusion in the study. Creatinine clearance by the Cockcroft–Gault Equation (16) on the basis of serum creatinine and body weight measured within 1 year before or up to 90 days after enrollment was used for FDA dose recommendation for dabigatran and rivaroxaban in secondary analyses. During follow-up among warfarin users, time in therapeutic range was determined by the Rosendaal method (17). Labile international normalized ratios (INRs) were defined as time in therapeutic range <60%.

Outcomes Definitions

The outcomes were bleeding and ischemic stroke, ascertained by ICD-9-CM codes adapted from previous validation studies (18,19). A definite bleeding code without a corresponding trauma was used to define a bleeding event, and both major (i.e., bleeding at critical site [intracranial, retroperitoneal, intraspinal, intraocular, pericardial, or intraarticular] or bleeding requiring transfusion) and minor bleeding were included (18). The codes for bleeding and ischemic stroke have a positive predictive value of 89% and 90%, respectively (18,19).

Propensity Matching Procedure

A total of 3655 patients initiated direct oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban) since October 19, 2010. Eight were ineligible due to a missing or invalid death date (n=8). We then used 1:1 nearest-neighbor propensity score–matching techniques (a caliper of 0.25 propensity score SD) to match direct oral anticoagulant users to warfarin users (20). This procedure was repeated separately for each drug. A propensity score match was obtained for 3206 direct oral anticoagulant users. The baseline date was considered the first direct oral anticoagulant prescription date for direct oral anticoagulant users and the matched warfarin prescription date for warfarin users.

Statistical Analyses

The balance of baseline characteristics between the matched cohorts was assessed using the standardized mean difference, a measure not influenced by sample size; values<0.1 indicate a negligible difference between groups (21). Incidence rates for each outcome were compared between the matched cohorts by category of eGFR. Cox proportional hazards regression models, stratified by CKD status, were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of each outcome associated with direct oral anticoagulant use. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals (Supplemental Table 2).

In primary analysis, we censored participants at the first occurrence of a study outcome, death (ascertained via linkage to the National Death Index), prescription for a different anticoagulant, medication discontinuation, or end of the study period (i.e., as-treated analyses). In sensitivity analyses, we: (1) used an intention-to-treat approach, (2) used time-varying drug exposure, (3) excluded those on dialysis and censored at dialysis initiation, (4) excluded those with an AKI diagnostic code within 3 months of the baseline serum creatinine, (5) used an average eGFR instead of a single eGFR, (6) used a 30-day gap for defining medication discontinuation, (7) excluded those with rheumatic mitral stenosis or prosthetic heart valve, and (8) stratified by prior anticoagulation history.

We also assessed the proportion of direct oral anticoagulant dose by eGFR and proportion taking the FDA recommended level of direct oral anticoagulant dose. Cumulative incidence of treatment change during the study period was estimated accounting for competing events of treatment change (i.e., discontinuation, switch to warfarin, or switch to other direct oral anticoagulants), because these three were mutually exclusive. All analyses were conducted using Stata/MP 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Geisinger Institutional Review Board as well as the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board.

Results

Prevalence of Direct Oral Anticoagulant Use over Time by eGFR Category

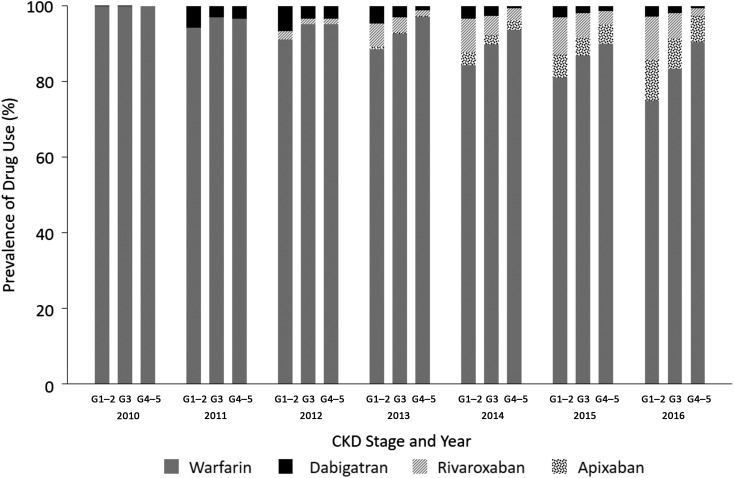

Among the 20,727 patients with atrial fibrillation, prescription of direct oral anticoagulants increased from 0.05% to 21% from 2010 to 2016, including within each category of eGFR (all P<0.001) (Figure 1). Among those with eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, the most frequently prescribed drug in 2016 was rivaroxaban (11%), followed by apixaban (10%) and dabigatran (3%). Among those with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, apixaban was the most frequently prescribed (8% versus 6% and 2% for rivaroxaban and dabigatran, respectively). Thirty-five percent of direct oral anticoagulant users had eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Figure 1.

Direct oral anticoagulant prescriptions increased over time among patients with atrial fibrillation in all stages of CKD in the Geisinger Health System (n=20,727). The total number of patients in each year from 2010 to 2016 was 6622, 6826, 7282, 7964, 8445, 8781, and 9001, respectively. CKD stage G1–2: eGFR≥60, G3: eGFR 30–59, and G4–5: eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2.

Characteristics of Direct Oral Anticoagulant Users

The mean (SD) age of new direct oral anticoagulant users was 70 (12) years, 45% were female, 97% were white, and mean (SD) eGFR was 70 (22) ml/min per 1.73 m2 (Supplemental Table 3). At baseline, 2484 (68%), 1038 (28%), and 130 (4%) had eGFR≥60, eGFR 30–59, and eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. By type of drugs, 880 (24%), 1560 (43%), and 1207 (33%) were initially prescribed dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban. On average, dabigatran and rivaroxaban users were similar; however, apixaban users were older, more often women, and had slightly lower eGFR, higher CHA2DS2–VASc score, and higher HAS-BLED score than the other direct oral anticoagulant users. Approximately 34% of direct oral anticoagulant users had a history of warfarin use (median duration [interquartile range], 3 years [1–6]). Direct oral anticoagulant users with a history of warfarin use, on average, had a higher risk profile than warfarin-naïve direct oral anticoagulant users (Supplemental Table 4).

Analyses Using the Matched Cohorts

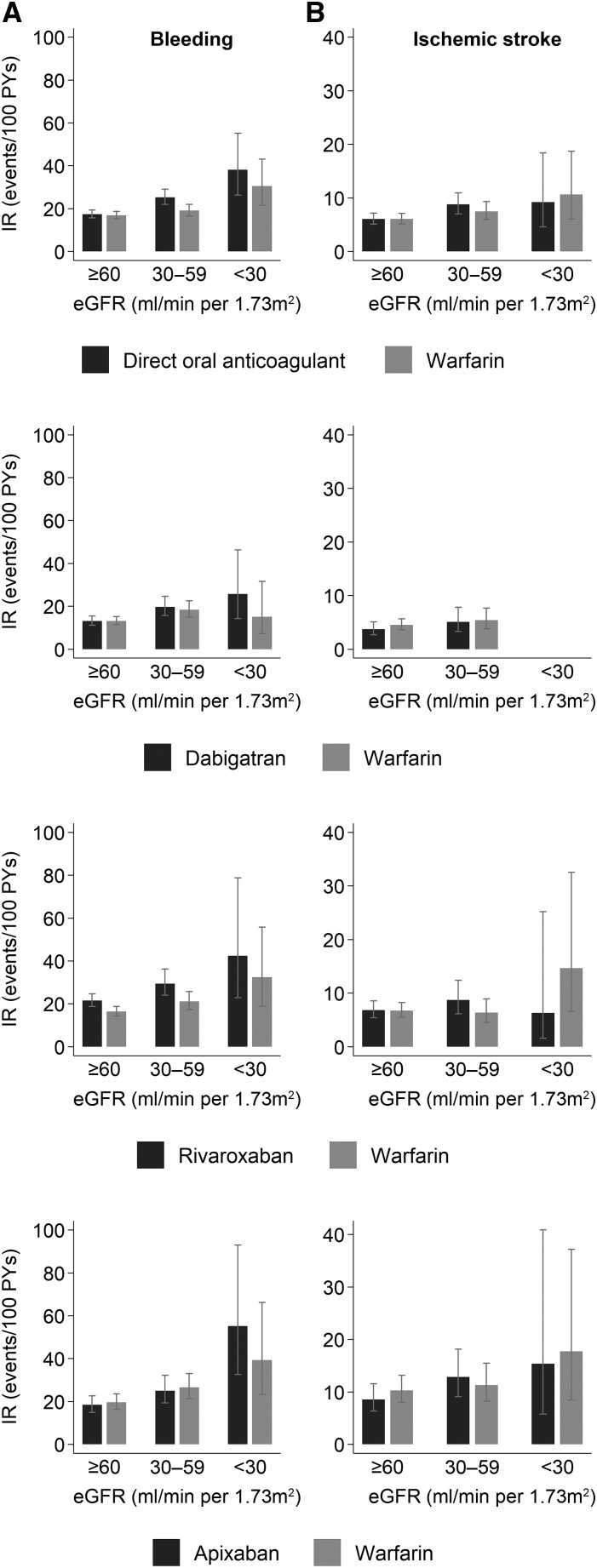

Appropriate warfarin-using matches were found for 3206 (88%) of the direct oral anticoagulant users, resulting in matched cohorts closely balanced for all baseline covariates (Supplemental Tables 5–7, Table 1, all standardized mean differences <0.1). Among 3206 warfarin users, 3016 (94%) had the laboratory data of INR control. Overall, 57% of warfarin users had labile INRs and those with lower eGFR had worse anticoagulation control (67%, 54%, and 57% had labile INRs with eGFR<30, 30–59, and ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively). There were 1181 bleeding events (incidence rate [direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin]=20.0 versus 17.9 per 100 person-years) and 466 ischemic strokes (incidence rate=6.9 versus 6.6) among 6412 patients with 7391 person-years of follow-up (average [SD] follow-up time=1.2 [1.3] years). The incidence rates (95% CI) of bleeding were 17.3 (15.7 to 19.3) versus 16.8 (15.3 to 18.6) among the 4169 people with eGFR≥60, 25.2 (21.9 to 29.0) versus 19.0 (16.4 to 21.9) among the 1990 people with eGFR 30–59, and 38.1 (26.3 to 55.2) versus 30.4 (21.5 to 43.0) for the 253 people with eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively (Figure 2A). When stratified by CKD status, the HRs (95% CI) of bleeding for direct oral anticoagulant compared with warfarin users were 1.01 (0.88 to 1.17) and 1.23 (1.02 to 1.48) in eGFR≥60 and eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively (P-for-interaction=0.10, Table 2). The incidence rates of ischemic stroke (95% CI) were 6.0 (5.1 to 7.1) versus 6.0 (5.1 to 7.1), 8.8 (7.0 to 10.9) versus 7.5 (6.0 to 9.3), and 9.2 (4.6 to 18.4) versus 10.6 (6.0 to 18.7) for those with eGFR≥60, eGFR 30–59, and eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively (Figure 2B). The HRs (95% CI) of ischemic stroke were 0.94 (0.74 to 1.18) and 1.02 (0.76 to 1.37) for those with eGFR≥60 and eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively (P-for-interaction=0.70). Similar findings were observed when each drug was analyzed individually. The results were consistent when intention-to-treat or time-varying drug exposure analyses were done (Table 2). Additional sensitivity analyses showed similar findings: analyses excluding those on dialysis at baseline and censoring at dialysis initiation (Supplemental Table 8), exploring potential effects of misclassification of baseline eGFR (Supplemental Table 9), using an alternative gap (30 days) for defining medication discontinuation (Supplemental Table 10), and excluding those with valvular atrial fibrillation (Supplemental Table 11). There was limited sample size in stratified analyses by prior anticoagulation history with no significant results (Supplemental Table 12).

Figure 2.

Patients with low eGFR on direct oral anticoagulants for treatment of atrial fibrillation experienced bleeding events more frequently than those on warfarin, but had similar rates of ischemic stroke. Incidence rates of bleeding (A) and ischemic stroke (B) by eGFR category among propensity-score matched patients with atrial fibrillation using direct oral anticoagulants or warfarin. IR, incidence rate; PYs, person-years.

Table 2.

Risk of outcomes among patients receiving direct oral anticoagulants versus warfarin, overall and stratified by eGFR

| Outcome | Number of Events | IR, per 100 PYs | HR (95% CI) | P Value | P-inter | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Oral Anticoagulants | Warfarin | Direct Oral Anticoagulants | Warfarin | ||||

| All bleeding (all/major/minor) | |||||||

| Analyses 1 | |||||||

| Overall | 574/76/498 | 607/126/481 | 20.0/2.7/17.3 | 17.9/3.7/14.2 | 1.08 (0.97 to 1.22) | 0.16 | |

| eGFR≥60 | 350/39/311 | 390/76/314 | 17.3/1.9/15.4 | 16.8/3.3/13.5 | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.17) | 0.88 | 0.10 |

| eGFR<60 | 224/37/187 | 217/50/167 | 26.3/4.4/21.9 | 20.1/4.6/15.5 | 1.23 (1.02 to 1.48) | 0.03 | |

| Analyses 2 | |||||||

| Overall | 863/111/752 | 805/155/650 | 14.9/1.9/13.0 | 13.8/2.7/11.1 | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.20) | 0.08 | |

| eGFR≥60 | 537/63/474 | 520/93/427 | 12.9/1.5/11.4 | 12.7/2.3/10.4 | 1.03 (0.91 to 1.16) | 0.65 | 0.11 |

| eGFR<60 | 326/48/278 | 285/62/223 | 20.0/2.9/17.1 | 16.3/3.6/12.7 | 1.21 (1.03 to 1.42) | 0.02 | |

| Analyses 3 | |||||||

| Overall | 574/76/498 | 740/142/740 | 16.8/2.2/14.6 | 15.1/2.9/12.2 | 1.18 (1.05 to 1.31) | 0.004 | |

| eGFR≥60 | 350/39/311 | 475/87/388 | 14.7/1.6/13.0 | 14.1/2.6/11.5 | 1.11 (0.96 to 1.27) | 0.15 | 0.10 |

| eGFR<60 | 224/37/187 | 265/55/210 | 21.8/3.6/18.2 | 17.2/3.6/13.6 | 1.33 (1.11 to 1.58) | 0.002 | |

| Ischemic stroke | |||||||

| Analyses 1 | |||||||

| Overall | 222 | 244 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 0.97 (0.81 to 1.16) | 0.72 | |

| eGFR≥60 | 136 | 152 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.18) | 0.59 | 0.70 |

| eGFR<60 | 86 | 92 | 8.8 | 7.8 | 1.02 (0.76 to 1.37) | 0.91 | |

| Analyses 2 | |||||||

| Overall | 305 | 301 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 1.00 (0.83 to 1.17) | 0.99 | |

| eGFR≥60 | 191 | 193 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 0.97 (0.79 to 1.18) | 0.73 | 0.57 |

| eGFR<60 | 114 | 108 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 1.06 (0.82 to 1.38) | 0.64 | |

| Analyses 3 | |||||||

| Overall | 222 | 282 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 0.94 (0.79 to 1.12) | 0.48 | |

| eGFR≥60 | 136 | 180 | 6.1 | 5.6 | 0.89 (0.71 to 1.11) | 0.30 | 0.49 |

| eGFR<60 | 86 | 102 | 8.8 | 6.8 | 1.03 (0.77 to 1.37) | 0.85 | |

Analyses 1: as-treated analyses; analyses 2: intention-to-treat analyses; analyses 3: time-varying analyses. IR, incidence rate; PY, person-years; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; P-inter, P-for-interaction.

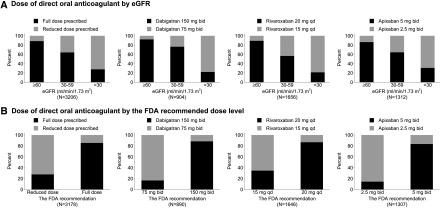

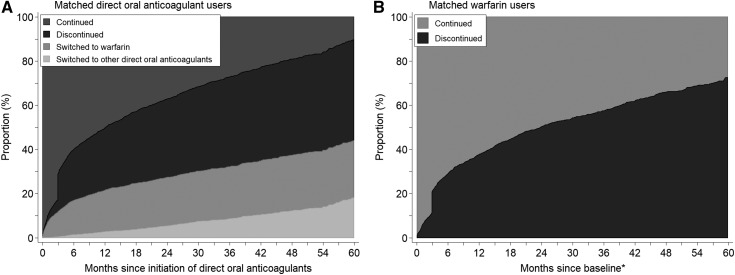

Overall, 21% of direct oral anticoagulant users were prescribed a reduced dose. Only 11% were prescribed a reduced dose among direct oral anticoagulant users with eGFR≥60, whereas 36% and 72% were prescribed a reduced dose among those with eGFR 30–59 and eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (Figure 3A). Among direct oral anticoagulant users with eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, 22% of dabigatran users, 21% of rivaroxaban users, and 31% of apixaban users received full dose. Approximately 11% of direct oral anticoagulant users needed dose reduction according to the FDA recommendations. Among those who needed dose reduction, 17% of dabigatran users, 35% of rivaroxaban users, and 15% of apixaban users received inappropriately a full dose (Figure 3B). At 1 year after initiation of direct oral anticoagulants, 3% had switched to other direct oral anticoagulants, 19% had switched to warfarin, and 28% had discontinued them (Figure 4). In comparison, at 1 year of follow up, 38% of warfarin users had discontinued use.

Figure 3.

Pattern of prescribed direct oral anticoagulant dose by eGFR and the FDA recommended dose level. Adding the sample size of cohort of each drug in (A) does not give 3206, the total number of matched direct oral anticoagulant users, because individuals changing from one type to the others were included in two or three different cohorts of each drug. The sample sizes in (B) are slightly smaller than those in (A) due to missing body weight. The current FDA dosing guidelines were applied to all past dosing of each direct oral anticoagulant: Dabigatran 150 mg twice a day and 75 mg twice a day for those with creatinine clearance >30 and creatinine clearance 15–30 ml/min, respectively. Rivaroxaban 20 mg every day and 15 mg every day for those with creatinine clearance >50 and creatinine clearance 15–50 ml/min, respectively. Apixaban 5 mg twice a day unless dose reduction is recommended. Apixaban 2.5 mg twice a day for those with at least two of the following conditions: age≥80 years, body wt ≤60 kg, or serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dl. FDA, Food and Drug Administration.

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence of treatment change during follow-up among matched direct oral anticoagulant users and warfarin users with atrial fibrillation. *Baseline time for warfarin users (A) is the warfarin prescribed date matched with duration of previous warfarin use, in comparison with direct oral anticoagulant users (B). Thirty-nine percent of discontinuation of anticoagulant occurred after bleeding events.

Discussion

Despite sparse evidence of safety and effectiveness in patients with atrial fibrillation and CKD, we demonstrate that prescription of direct oral anticoagulants has increased substantially within all categories of eGFR in a health care setting. In our real-world data, approximately 20% of all patients with atrial fibrillation treated with anticoagulation received a prescription for a direct oral anticoagulant in 2016, including 17% and 10% of those with eGFR 30–59 and <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. Compared with propensity-matched warfarin users, direct oral anticoagulant use resulted in similar benefit in terms of ischemic stroke prevention but was associated with a 23% higher risk of bleeding among those with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. These findings might suggest the need for heightened caution in prescribing and monitoring of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with CKD.

Our results add to a recent study which showed increased prescription of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and advanced CKD, despite the most recent American Heart Association (AHA), American College of Cardiology (ACC), and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommending against the use of direct oral anticoagulants when creatinine clearance <30 ml/min (1,2). The previous analysis reported the most commonly used direct oral anticoagulant in 2015 was apixaban (10%), followed by rivaroxaban (9%) and dabigatran (3%), but they did not measure bleeding rates or ischemic stroke prevention (22). Our findings of a trend toward higher bleeding risk and similar benefit in ischemic stroke prevention in CKD support the current guidelines, which recommend refraining from direct oral anticoagulant use in patients with atrial fibrillation and advanced CKD.

Although the US FDA provides dosing for direct oral anticoagulants when creatinine clearance is as low as 15 ml/min for dabigatran and rivaroxaban and <15 ml/min for apixaban, the FDA labeling was mostly on the basis of small, single-dose pharmacokinetics studies without clinical trial outcomes data (23–26). Moreover, labels by the European Medicines Agency do not support this practice. None of the three pivotal direct oral anticoagulant trials showed higher risk of bleeding in subgroups of patients with moderate CKD (creatinine clearance <50 ml/min), and all showed a trend toward lower risk of ischemic stroke (27–29). However, in one of these trials, when eGFR was assessed continuously, bleeding risk was higher among dabigatran users compared with warfarin users with eGFR<50 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (27). In our study, direct oral anticoagulant use was significantly associated with higher risk of bleeding among those with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and a trend toward higher risk of bleeding was consistently observed across three types of drugs with lower eGFR. On the other hand, we found no difference in ischemic stroke prevention between direct oral anticoagulant and warfarin users in any eGFR category. We note that our study population was quite different from that of the clinical trials, all of which excluded patients with advanced CKD and certain types of valvular heart disease, although it is clear that many of the patients who might be eligible for direct oral anticoagulant prescription have these conditions in real-world practice (11,30). We found 28% of patients recommended to receive dose reduction by the FDA recommendation were prescribed full-dose therapy. This might be because the FDA recommends drug dose on the basis of creatinine clearance, whereas GFR is widely being used in clinical practice.

Our study is the first study to evaluate risks and benefits of direct oral anticoagulants across the spectrum of GFR in patients with atrial fibrillation, using a heterogeneous but stable study population from a large health care system. Rigorous propensity score–matching techniques were used to create a cohort with comparable characteristics between treatment groups, minimizing bias. Moreover, our study’s follow-up began right from FDA approval, affording us some of the longest follow-up times possible. However, there are also certain limitations. First, our study is observational. Despite propensity score matching, direct oral anticoagulant users may differ from warfarin users in unidentified ways that relate to the risk of bleeding or ischemic stroke (e.g., treatment adherence). Second, analyzing only one health care system which included few (n=123, 2%) nonwhite patients limits the generalizability of our findings. Third, we had few patients with eGFR<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, precluding many analyses in this subgroup. Forth, our study population included direct oral anticoagulant users both with and without history of previous anticoagulation. Although pharmacoepidemiology studies often utilize a new user design to mitigate chronology bias, we included all users because we aimed to assess safety and effectiveness in real-world settings, where many direct oral anticoagulant users switch from warfarin. Further, to address this potential source of bias, we matched on duration of previous anticoagulation, which enabled comparisons at a comparable time in the natural history of their treatment. Fifth, outcomes were identified through the use of ICD-9-CM codes. However, we adapted ICD-9-CM codes for outcome ascertainment from previous validation studies (18,19). If misclassification of outcomes exists, it would be expected to be nondifferential, thus our observed associations are conservative. Finally, we did not assess risk of site-specific bleeding (e.g., gastrointestinal bleeding or intracranial hemorrhage).

In conclusion, we report a higher bleeding risk and similar ischemic stroke prevention with direct oral anticoagulants compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation with eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in a clinical practice setting. These findings lend support to the current clinical guidelines by AHA/ACC and ESC, which suggest refraining from direct oral anticoagulant use for treatment of atrial fibrillation in advanced CKD, and raise safety concerns regarding the current US FDA labels. Further large-scale studies are warranted to confirm our findings. For now, we suggest caution in prescribing direct oral anticoagulants for patients with advanced CKD.

Disclosures

G.C.A. is Chair of the US Food and Drug Administration’s Peripheral and Central Nervous System Advisory Committee; has served as a paid consultant to IQVIA and serves on the Advisory Board of MesaRx Innovations; holds equity in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation; and serves as a member of OptumRx’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers T32 HL007024, R01 DK100446, K08 DK092287).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.13811217/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Camm AJ, Lip GYH, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) : 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: An update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J 33: 2719–2747, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jr ., Conti JB, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz MD, Field ME, Murray KT, Sacco RL, Stevenson WG, Tchou PJ, Tracy CM, Yancy CW; ACC/AHA Task Force Members : 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 130: 2071–2104, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI: Meta-analysis: Antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 146: 857–867, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher AM, van Staa TP, Murray-Thomas T, Schoof N, Clemens A, Ackermann D, Bartels DB: Population-based cohort study of warfarin-treated patients with atrial fibrillation: Incidence of cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes. BMJ Open 4: e003839, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hylek EM, Go AS, Chang Y, Jensvold NG, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE: Effect of intensity of oral anticoagulation on stroke severity and mortality in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 349: 1019–1026, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hylek EM, Evans-Molina C, Shea C, Henault LE, Regan S: Major hemorrhage and tolerability of warfarin in the first year of therapy among elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation 115: 2689–2696, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J, Wang S, Alings M, Xavier D, Zhu J, Diaz R, Lewis BS, Darius H, Diener HC, Joyner CD, Wallentin L; RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators : Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 361: 1139–1151, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Berkowitz SD, Fox KA, Califf RM; ROCKET AF Investigators : Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365: 883–891, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A, Bahit MC, Diaz R, Easton JD, Ezekowitz JA, Flaker G, Garcia D, Geraldes M, Gersh BJ, Golitsyn S, Goto S, Hermosillo AG, Hohnloser SH, Horowitz J, Mohan P, Jansky P, Lewis BS, Lopez-Sendon JL, Pais P, Parkhomenko A, Verheugt FW, Zhu J, Wallentin L; ARISTOTLE Committees and Investigators : Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 365: 981–992, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart RG, Eikelboom JW, Ingram AJ, Herzog CA: Anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation patients with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 569–578, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawkins NM, Jhund PS, Pozzi A, O’Meara E, Solomon SD, Granger CB, Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Petrie MC, Virani S, McMurray JJ: Severity of renal impairment in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation: Implications for non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant dose adjustment. Eur J Heart Fail 18: 1162–1171, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJGM: Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: The euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 137: 263–272, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJGM, Lip GYH: A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: The Euro Heart Survey. Chest 138: 1093–1100, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group: KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3: 1–150, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH: Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 16: 31–41, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briët E: A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost 69: 236–239, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham A, Stein CM, Chung CP, Daugherty JR, Smalley WE, Ray WA: An automated database case definition for serious bleeding related to oral anticoagulant use. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 20: 560–566, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tirschwell DL, Longstreth WT Jr .: Validating administrative data in stroke research. Stroke 33: 2465–2470, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin DB, Thomas N: Matching using estimated propensity scores: Relating theory to practice. Biometrics 52: 249–264, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin PC: Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med 28: 3083–3107, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan KE, Giugliano RP, Patel MR, Abramson S, Jardine M, Zhao S, Perkovic V, Maddux FW, Piccini JP: Nonvitamin K anticoagulant agents in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease or on dialysis with AF. J Am Coll Cardiol 67: 2888–2899, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Tirucherai G, Marbury TC, Wang J, Chang M, Zhang D, Song Y, Pursley J, Boyd RA, Frost C: Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of apixaban in subjects with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. J Clin Pharmacol 56: 628–636, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang M, Yu Z, Shenker A, Wang J, Pursley J, Byon W, Boyd RA, LaCreta F, Frost CE: Effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of apixaban. J Clin Pharmacol 56: 637–645, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kubitza D, Becka M, Mueck W, Halabi A, Maatouk H, Klause N, Lufft V, Wand DD, Philipp T, Bruck H: Effects of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor. Br J Clin Pharmacol 70: 703–712, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hariharan S, Madabushi R: Clinical pharmacology basis of deriving dosing recommendations for dabigatran in patients with severe renal impairment. J Clin Pharmacol 52[Suppl]: 119S–125S, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hijazi Z, Hohnloser SH, Oldgren J, Andersson U, Connolly SJ, Eikelboom JW, Ezekowitz MD, Reilly PA, Siegbahn A, Yusuf S, Wallentin L: Efficacy and safety of dabigatran compared with warfarin in relation to baseline renal function in patients with atrial fibrillation: A RE-LY (Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulation Therapy) trial analysis. Circulation 129: 961–970, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hohnloser SH, Hijazi Z, Thomas L, Alexander JH, Amerena J, Hanna M, Keltai M, Lanas F, Lopes RD, Lopez-Sendon J, Granger CB, Wallentin L: Efficacy of apixaban when compared with warfarin in relation to renal function in patients with atrial fibrillation: Insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. Eur Heart J 33: 2821–2830, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fox KA, Piccini JP, Wojdyla D, Becker RC, Halperin JL, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Hankey GJ, Mahaffey KW, Patel MR, Singer DE, Califf RM: Prevention of stroke and systemic embolism with rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and moderate renal impairment. Eur Heart J 32: 2387–2394, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lip GY, Laroche C, Dan GA, Santini M, Kalarus Z, Rasmussen LH, Oliveira MM, Mairesse G, Crijns HJ, Simantirakis E, Atar D, Kirchhof P, Vardas P, Tavazzi L, Maggioni AP: A prospective survey in European Society of Cardiology member countries of atrial fibrillation management: Baseline results of EURObservational Research Programme Atrial Fibrillation (EORP-AF) Pilot General Registry. Europace 16: 308–319, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.