Abstract

Objective:

Research on biases in attention related to children’s aggression has yielded mixed results. Some research suggests that inattention to social cues and reliance on maladaptive social schemas underlie aggression. Other research suggests that maladaptive social schemas lead aggressive individuals to attend to non-hostile cues. The primary objective of this study was to test the proposition that aggression is related todelayed attention to cuesfollowed by selective attention to non-hostile cues after the provocation has occurred. A second objective was to test whether these biases are associated with aggression only when children hold negative social schemas.

Method:

The eye fixations of seventy children (34 boys; 36 girls; Mage =11.71 years) were monitored with an eye tracker as they watched video clips of child actors portraying scenes of ambiguous provocation. Aggression was measured using peer-, teacher-, and parent-reports, and children completed a measure of antisocial and prosocial peer beliefs.

Results:

Aggressive behavior was associated withgreater time until fixation on the provocateur among youth who held antisocial peer beliefs. Aggression was also associated with greater time until fixation onan actor displaying empathy for the victim among children reporting low levels of prosocial peer beliefs. After the provocation, aggression was associated with suppressed attention to an amused peer among children who held negative peer beliefs.

Conclusions:

Increasing attention to cues in a scene of ambiguous provocation, in conjunction with fostering more positive beliefs about peers, may be effective in reducing hostile responding among aggressive youth.

Keywords: aggression, externalizing disorders, peer relationships

Aggression in childhood not only causes distress for the victims, but alsocan lead to long-term difficulties for its perpetrators, includingacademic failure, substance abuse, employment difficulties, and criminal behavior (Broidy et al., 2003; Cairns, Cairns, &Neckerman, 1989; Kokko&Pulkkinen, 2000). To better understand the ontogeny of aggression, researchers have amassed a large literature on the physiological, emotional, and contextual factors underlying aggressive behavior (Loeber& Hay, 1997; McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, Mennin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 201; Raine, 2005). As social information-processing (SIP) theories gained prominence in the 1980s and 1990s (e.g., Crick & Dodge, 1994; Rubin &Krasnor, 1986), the study of cognitive factors came to the forefront of research on aggression. These models posit that differences in interpersonal behavior arise from differences in the information to which individuals attend and the subsequent, step-wise processing of that information (e.g., causal attributions, goal construction). Thus, aggression is believed to arise, in part, frombiases in attention to social cues, as well as from the succeeding processing of those cues(Crick & Dodge, 1994).

Although biasesin the allocation of attention are believed to instigateaggressogenic processing of information, it is this first step of SIP models that has received the least amount of empirical study (Horsley, Orobio de Castro, & Van der Schoot, 2010; Pettit, Polaha, & Mize, 2001). Moreover, the research that has been conducted has yielded varying findings, in part due to the differing methodologies employed. Thus, unlike other stages of social information processing in which distinct deficits underlying aggression have been identified (e.g., hostile attribution biases, response evaluation; Crick & Dodge, 1994), there remain competingideas as to the nature of attentional biases contributing to aggression. The objective of thisstudy was to use eye tracking to test a unified account of how biases in attention relate to aggressive behavior.

Inattention versus Selective Attention to Social Cues

In their seminal paper on SIP, Crick and Dodge (1994) proposed two potential means by which deficits in attention to social cues may result in aggressive behaviors: a) aggression may result fromheightened attention to hostile cues, or b) aggression may result from relyingon well-developed social schemas to interpret events rather than attending to and utilizing available social cues to base interpretations. Although early research supported the former proposition (Dodge & Newman, 1981; Dodge & Price, 1994; Gouze 1987), researchers began to identify a lack of attention to relevant cues as a significant correlate of aggression. Notably, in a series of studies using video recordings of negative interactions, Dodge and colleagues (e.g., Dodge, Lochman, Harnish, Bates, & Pettit, 1997; Weiss, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1992) found that aggression is associated with poor recall for relevant social information. In addition, aggressive children have been shown to base interpretations for events on their personal schemas, rather than on available information, and misremember information in ways consistent with those schemas (Dodge & Frame, 1982; Dodge & Tomlin, 1987). Researchers, therefore, concluded that aggressive children rely on their social schemas, rather than attending to available social cues, to interpret events.

There is also evidence that aggressive children’s inattention to relevant stimuli is greatest for those events occurring prior to, rather than concurrent with, a provocation. Dodge and Tomlin (1987) tested early adolescents’ utilization and recall of cues presented through audiorecordings of hypothetical negative events. They found that aggressive participants recalled and utilized cues temporally proximal to the event (i.e., recency cues) at rates equal to their non-aggressive peers. However, the aggressive adolescents evidenced recall deficits for, and underutilized, primacy cues (i.e., cues presented early in the vignettes). Milich and Dodge (1984) similarly found that aggressive/hyperactive boys remember proportionally more cues recent to a provocation than those presented earlier.

Although potentially reflecting biases in memory for cues, problematic recall of early cues may stem from biases in attentionduring initial scene perception.The first few seconds of scene perception are characterized by an “ambient mode” in which individualsmake numerous, short fixations across a widespan of the visual field (Pannasch, Helmert, Roth, Herbold, & Walter, 2008). It is during the ambient mode that the gist of the scene is believed to beacquired. This is followed by a “focal mode” in which a few, longer fixations are concentrated in a smaller region of the visual field (Pannasch et al., 2008). One possibility is that aggressive children begin their viewing of social scenes in a focal mode, leading to delayed attention to available social cues. As more focused attentionalso reduces the likelihood that relevant cues will capture attention (Belopolsky, Zwaan, Theeuwes, & Kramer, 2007), aggressive children may be slower than non-aggressive children to attend to cues of greatest importance for interpreting the social scene, including earlypresented cues that may indicate non-hostile intentions.Thus, this pattern of attention would explain why aggressive children have poor recall for cues presented early in a provocation compared to their peers (Dodge & Tomlin, 1987; Milich& Dodge, 1984).

To address limitations in relying on memory recall paradigms, researchers have begun utilizing more direct assessments of attention. The findings from these studies suggest a third possible pattern of attention biases among aggressive children – inattention to hostile cues and heightened attention to non-hostile cues. Using a probe detection task, Schippell et al. (2003) found that among early-to-mid-adolescents, reactive aggression and a bias to interpret ambiguous situations as hostile are associated with suppressed attention to socially threatening words. Wilkowski, Robinson, Gordon, and Troop-Gordon (2007) used eye tracking to assess the attention of 45 undergraduate males as they viewed line drawings depicting scenes of ambiguously aggressive acts. Each drawing included a hostile and non-hostile cue. The researchers found that participants high in trait anger spent more time attending to non-hostile than hostile cues. Horsley et al. (2010) conducted a similar eye tracking study with elementary school children. Using cartoon displays of ambiguous provocation, they found that children high in aggression attended longer to non-hostile cues than to hostile ones.

These findings are in accordance with scene perception research showing that an object whose identity is incongruous with the scene in which it is embedded (e.g., a lawnmower in a classroom) draws attention during scene exploration (Gordon, 2006; Underwood, Humphreys, & Cross, 2007). Cognitive psychologists have suggested that incongruous cues within a scene draw attention as the individual tries to identify or interpret the meaning of the inconsistent object in light of conflicting scene information (Gordon, 2006). Drawing on this research,Wilkowski et al. (2007) and Horsley et al. (2010) concluded that aggressive children make quick, hostile interpretations of ambiguously aggressive scenes. Once this interpretation is made, their attention is then drawn to non-hostile cues that are inconsistent with that interpretation.

Thus, there is compelling evidence suggesting that aggression is associated with both delayed attention to social cues and heightened attention to non-hostile cues. However, rather than reflecting competing explanations for the role of attention in aggressive behavior, these findings may reflect related, but distinct, attentional biases that work in tandem to elicitaggressive behavior. We propose that the nature of attentional biases supporting aggression shift over the course of a provocation. Specifically, consistent with Dodge and Tomlin (1987) and Milich and Dodge (1984), prior to a provocation, aggression may be related to greater time until attentionto available social cues. However, once a provocation has occurred and an interpretation of the event has been construed, attention is drawn to cuesinconsistent with that interpretation (Horsley et al., 2010; Wilkowski et al., 2007).

The first goal of this study, therefore, was to test the proposition that: (a)delayed attention to social cues, and (b) selective attention to non-hostile cues following a provocation are associated with higher levels of aggression. To test this proposition,dynamic displays of provocation were needed to identify attention processes occurring early in a provocation (i.e., distally displayed cues) and those occurring after the provocation. To this end, the current study used video clips of child actors acting out scenes of ambiguous provocation and eye tracking to provide a nearly-continuous recording of attention in real time. Prior to the provocation, actors in the video clips maintained neutral expressions. Thus, although the intent of the provocation was unclear, early cues allowed for a possiblebenign interpretation of the event.

To test the second part of the proposition, hostile and non-hostile cues needed to be displayed after the provocation. In previous studies, researchers accomplished this by depicting hostile and non-hostile cuessimultaneously as features of the provocateur (e.g., a provocateur kicking a ball at a window while simultaneously looking away; Horsley et al., 2010; Wilkowski et al., 2006). However, having a provocateur display conflicting cues simultaneously in real time is difficult and lacks face validity. Thus, in each scene, the provocateur maintained a neutral expression (i.e., non-hostile cue). Two additional cues were also included that would indicate that a hostile action had taken place, an actor who displayed amusement at the victim’s distress and an actor who displayed empathy toward the victim. We hypothesized that aggression would be associated with greater time until fixation onallactors. We also hypothesized that aggression would be positively correlated with attention after the provocation on the provocateur, whose neutral display was inconsistent with an interpretation of hostile intent, and negatively with attention after the provocation on the amused and empathetic peers. In order to account for the possibility that associations between aggression and attention biasesare due to underlying attention problems, we further examined these associations controlling for parent- and teacher-rated attention problems.

Attention and Aggression: The Moderating Role of Social Schemas

Social schemas are central to understanding why both inattention to social cues and selective attention to non-hostile cues would be associated with aggression. Poor attention to social cues is believed to lead to aggression because aggressive children “fill in the gaps” by engaging social schemas in top-down processing of the social environment (Crick & Dodge, 1984). Aggression is believed to be associated with inattention to hostile cues and heightened attention to non-hostile cues after the provocation occurs because attention is being directed toward stimuli inconsistent with negative social schemas. Therefore, greater time until fixation onsocial cues and selective attention after the provocation should be associated with aggression only if children also have negativebeliefs about their peers. However, researchers have yet to directly assess social schemas and their role in the link between attention and aggression.

Thus, a second major objective of this study was to test whether aggression is associated with attentionto social cues when children hold negative social schemas. To test this proposition, we drew upon Rabiner and colleagues’ (MacKinnon-Lewis, Rabiner, & Starnes, 1999; Rabiner, Keane, & MacKinnon-Lewis, 1993) conceptualization of children’s peer schemas as encompassing beliefs regarding peers’ antisocial behavior (i.e., the belief that peers frequently act meanly, start fights, and boss others around) and prosocial behavior (i.e., belief that peers are kind, cooperative, and caring). As expected, holding greater antisocial peer beliefs and lower prosocial peer beliefsis associated with aggressive behavior and externalizing problems (Salmivalli, Ojanen, Haanpää, &Peets, 2005; Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2005).

Although in previous research measures of antisocial and prosocial peer beliefs have been combined to create an assessment of global peer beliefs (e.g., Rabiner et al., 1993; Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2005), it was expected that antisocial and prosocial peer beliefs may be differentially applied to the interpretation of the ambiguous provocations. Antisocial peer beliefs are likely highly integral for interpreting the intention of the provocateur (i.e., the likelihood that the provocateur intentionally acted out of malice). In contrast, interpretation of the behavior of onlookers may be more strongly influenced by prosocial peer beliefs (i.e., to what extent do others show compassion to a peer). Thus, it was hypothesized that time until fixation on the provocateur would be associated with greater aggression for those children high in antisocial peer beliefs. Time until fixation on the empathic and amused peers was expected to be associated with greater aggression among children low in prosocial peer beliefs. In addition, attention to the provocateur after the provocation was expected to be associated with aggression at high levels of antisocial peer beliefs, and inattention to the amused and empathetic peers was expected to be associated with aggression at low levels of prosocial peer beliefs.

Whereas the provocateur’s behavior and the empathy and amusement displayed by the bystanders have the potential to provide social cues that would aid in interpreting and responding to the ambiguous provocation, the victim’s response of distress provides little information as to whether the provocation was intentional. Therefore, social schemas of peers’ interpersonal dispositions have little bearing on understanding the victim’s behavior. Accordingly, social schemas were not expected to moderate associations between attention to the victim and aggression. However, attention to the victim was included in all analyses to test the specificity of the findings.

Methods

Participants

Data for this study came from 70 children residing in the upper-Midwest of the USA (34 boys; 36 girls;Mage = 11.71 years, SDage= 7.65 months; 94.3% Caucasian). Children came from primarily middle-class families with 5 (7.1%) reporting annual household incomes between $0 and $40,000, 19 (27.1%)between $41,000-$60,000, 21 (30.0%) between $61,000 and $80,000, and 22 (31.4%) reporting incomes greater than $80,000.

Children were recruited from a larger longitudinal study examining links between peer relationships and children’s emotional, behavioral, and school adjustment. The initial participation rate was 73.9%. Although a total of 464 children participated in the larger study, recruitment for this investigation focused on the 187 children who lived within a 20-minute drive to the university.Of these children, 69 (36.9%) had parents who agreed to bring their child to the lab. The majority of parents declining to participate stated a lack of time as their reason for not participating. A number of parents were not home or did not answer their phone when called. Parents from a school 45 minutes from campus were also contacted although fewer attempts were made to reach these parents due to the unlikelihood that they would be willing to travel such a far distance. Three parents agreed to participate, with the majority of parents contacted citing the long distance as their reason for not participating.Data from two participating children were not included in the final analyses due to missing peer belief data. No differences were found between the children participating in the eye tracking study and those who declined to participate on peer-rated aggression, teacher-rated aggression, antisocial or prosocial beliefs, or teacher-rated attention problems.

Apparatus and Stimuli

Video clips.

Stimuli for the eye tracking task included short video clips depicting 6 scenes of ambiguous provocation, 18 scenes of peer victimization, and 6 scenes of prosocial behavior (i.e., 30 scenes total). Each scene was acted out twice, once by four boy actors and once by four girl actors. Thus, a total of 60 video clips were created. Approximately 80 scenes were initially written. The final scripts used for this study were chosen based on piloting with four older elementary school-aged children (2 boys and 2 girls) who indicated which scenes were the most realistic and plausible. Each scene lasted approximately 12 seconds (M = 12.30; duration ranged from = 9.47 to 15.94 seconds for the ambiguous provocation video clips).

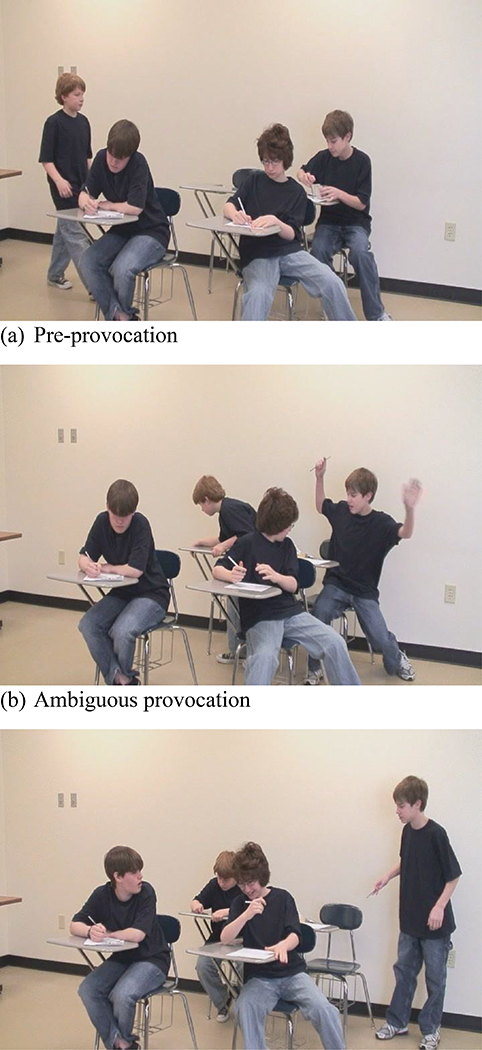

Each scene showed four children engaged in an interaction. Of the six ambiguous provocation scenes, three included a physical act of provocation – tripping someone, hitting with a ball during a game of catch, and knocking paint on a drawing -- and three included a verbal, more relational, act of provocation – not choosing someone for a team, telling someone that there isn’t room to sit at a lunch table, and pointing out mud on someone’s back. These scenes were based on hypothetical vignettes widely used in the SIP literature (e.g., Crick, 1995; Fitzgerald & Asher, 1987; Kirsch &Oczak, 2002). A detailed description of each one can be found in Appendix A, including the total time of each video clip and the amount of time until the provocation.Screen shots from one video clip is presented in Figure 1. In each scene, actors maintained neutral expressions prior to the provocation. Subsequent to the provocation, the victim showed distress, but the provocateur continued to display no emotions. Two additional peers were present in each scene. One showed empathy and concern for the target of the provocation. The second showed amusement and laughed at the provocation. On average, video clips lasted 5,979.92 ms after the initiation of the provocation.

Figure 1.

Still shots taken from video clip depicting Spilled Pain including the a) pre-event action, b) ambiguous provocation, and c) post-event display by the empathic and amused peers.

The eight child actors were recruited from local theater groups and were between 10 and 13 years old. All actors looked similar in age and had extensive training and experience in local theater productions. For each scene, actors were randomly assigned to a role; therefore, no actor could be associated with a particular role in the scenes (i.e., as a target of provocation). The actors wore jeans and identically colored, plaint-shirts provided by the researchers.

To examine whether actors displayed the relevant emotions and that a clear intent was not displayed by the provocateur, the 48 video clips showing peer victimization or ambiguous provocation were independently coded by two undergraduate assistants blind to the study’s hypotheses including the intended nature of the video clips. The coders rated each actor on three dimensions: a) intentionality of behavioron a scale from 1(definitely on purpose) to 5 (not at all on purpose), b) feelings about what happened on a scale from 1 (very badly) to 5 (very good), and c) amusement at the provocation on a scale from 1 (very amused) to 5 (not at all amused). The coders’ scores often ranged only two or three points, resulting inconstrained variance and low inter-rater reliability estimates even when the coders’ ratings were highly similar. Thus, we examined the coders’ ratings independently.

For both coders, ratings on intentionality were lower for the ambiguous provocation scenes than for the peer victimization scenes (for coder one and two, respectively: ambiguous provocations scenes,Ms = 3.17 and 3.08, SDs = .94 and 1.51; peer victimization scenes,Ms = 1.22 and M = 1.06, SDs = .54 and .33; t(46) = 8.87 and 7.69, ps< .001). The coders’ ratings of intentionality for the ambiguous scenes were very close to the 2.5 midpoint, suggesting no clear positive or negative intent.Repeated-measures ANOVAs showed that the actors varied significantly as to how badly they felt after the provocation, F(3,33) = 30.56, p < .001 and F(3,33) = 35.09, p < .001, for coder 1 and 2, respectively. The empathetic peer was viewed as feeling worse about the provocation (Ms= 2.25 and 2.42; SDs = .45 and .79) than the provocateur (Ms= 2.92 and 3.25; SDs = .67 and .62) and the amused peer (Ms= 3.83 and 3.92; SDs = .58 and .51), all ps< .05. However, the empathicpeer was perceived as showing less negative feelings than the victim (Ms= 1.75 and 1.33; SDs = .62 and .65). Repeated-measures ANOVA also showed that the amused peer displayed greater amusement in response to the provocation than the other actors, F(3,33) = 44.21, p < .001 and F(3,33) = 44.65, ps< .001, for coder 1 and 2, respectively. Coders rated the amused peer as more amused (Ms= 2.00 and 1.58; SDs = .43 and .51) than the provocateur (Ms= 2.83 and 3.25; SDs = .39 and .87), the target (Ms= 4.17 and 4.33; SDs = .72 and .65), and the empathetic peer (Ms= 3.42 and 4.08; SDs = .51 and .51), all ps< .001. In sum, the coders’ ratings confirmed that actors were displaying the desired emotions and behaviors.

Eye tracking.

The video clips were displayed to children on a NEC MultiSync FP2141SB monitor at a resolution of 1024 × 768 pixels and a refresh rate of 75 Hz. Children watched the video clips from a distance of 57 cm. A tower-mountedEyelink 1000 Eye Tracker (SR Research Ltd., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) was used to record participants’ eye movements, sampling gaze location at a rate of 1000 Hz. Video clips were presented to children in one of two randomly assigned orders. Children were informed that their eye location was going to be monitored as they watched the video clips. No other instructions were given, and participants were asked no questions regarding the individual video clips.

Measures

Visual attention to social cues.

For each participant, and for each of the 12 ambiguous provocation video clips, the location and duration of each fixation were recorded by trained research assistants. Fixations shorter than 100 ms were eliminated (3.28%). Two variables were calculated for each of the four target roles (i.e., provocateur, victim, empathicpeer, and amused peer). First, to assess delayed attention to each cue, the time until first fixation on each role was calculated. To ease interpretation, these scores were centered around the initiation of the provocation such that negative scores reflected first fixations that occurred prior to the provocation and positive scores reflected first fixations occurring after the initiation of the provocation. Thus, these centered scores provide a more concrete description of the extent to which first fixations on an actor were delayed relativeto the provocation. Post-provocation total dwell time was calculated as the average amount of time participants spent watching each actor after: a) the initiation of the injurious act for the provocateur and victim, and b) after first displaying empathy and amusement for the empathic and amused peers, respectively, to take into account small delays between the provocation and the display of the relevant emotion.

Aggression.

Aggression was measured using a combination of peer-report, teacher-report, and parent-report measures. Peer-reports of aggression were obtained from ratings children received from their classmates as part of the larger study. Four peer-rating items derived from Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd’s (2002) multi-informant peer victimization scales were administered to assess physical (“hits or pushes other kids”), verbal (“calls other bad names”), relational (“tells other kids they can’t play with them or be friends with them”), and general aggression (“picks on others”). These items are similar to those used in previous research (e.g., Bowker, Rubin, Buskirk-Cohen, Rose-Krasnor, & Booth-LaForce, 2010; Rose & Swenson, 2009), and have been shown to have good predictive validity in previous research with the larger sample from which the current participants were recruited [masked for blind review].For each item, children rated their participating classmates on a scale from 1 (never) to 4 (a lot). Mean scores for each item were calculated by averaging all ratings received from classmates. A composite aggression score was created by averaging across the four item scores (α = .94).

Teacher-reports of aggressive behavior were obtained using six items. Teachers rated each participating child on a scale from 1 (Never) to 4 (A lot of the time). Items included “threatens or bullies,” “spreads rumors or lies about other kids,” “acts aggressively toward peers,” “gets kids to gang up on a peer he/she doesn’t like,” “likes to boss other kids around,” and “tries to get other kids in trouble.” These items are consistent with other teacher-reports of aggressive behavior (e.g., Achenbach, 1991; Dodge &Coie, 1987), have shown good predictive validity in previous research [masked for blind review], and demonstrated good concurrent validity with the peer-report and parent-report measures of aggressive behavior used in this study. Ratings were averaged to create a composite aggression score (α = .93).

Parent-reports of aggression were obtained using 6 items from the aggression subscale from the Child Behavior Checklist, a well-validated measure of children’s aggressive behavior and externalizing problems (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991), and two additional items, “acts aggressively towards other kids” and “threatens or bullies others.” Items from the CBCL were chosen that focus on interpersonal aggression (e.g., gets into many fights, physically attacks people), rather than more general externalizing behaviors (e.g., disobedient at home). For each item, the accompanying parent provided a rating of 1 (Not true), 2 (Somewhat or sometimes true), or 3 (Very true or often true). Ratings on these 8 items were averaged to create a composite aggression score (α = .85).

Scores on the peer-report, teacher-report, and parent report measures were moderately correlated (r = .49, p< .001, between the peer-report and teacher-report measures; r = .37, p = .003, between the peer-report and parent-report measures; r = .37, p = .002, between the teacher-report and parent report measures). Scores on these three measures of aggressive behavior were averaged to create a composite aggression score (α = .55).

Peer beliefs.

Children’s peer beliefs were measured using the Peer Belief Inventorywhich has shown to have adequate internal reliability and predictive validity (MacKinnon-Lewis et al., 1999;Rabiner et al., 1993). This measure includes two 5-item subscales assessing children’s antisocial peer beliefs (e.g., “How much do the kids in your class like to act mean and hurt other kids’ feelings?”)and prosocial peer beliefs (e.g., “How much do the kids in your class share and don’t try to keep everything for themselves?”).Children responded to each item on a scale from 1 (Never) to 4 (A lot). A principal-axis factor analysis yielded a two-factor solution (eigenvalues = 3.52 and 1.19) in which the antisocial and prosocial items loaded on separate factors (all loadings ≥ .51). Ratings for the antisocial and prosocial peer belief items were averaged to create separate composite scores (αs = .88 and .82, respectively).

Attention problems.

Children’s attention problems were assessed using teacher- and parent-reports. Teachers rated children on three items, “is inattentive,” “has poor concentration or short attention span,” and “is restless and runs about or jumps up and down,” on a scale from 1 (Never) to 4 (A lot of the time). These items were taken from the four-item Hyperactive-Distractible subscale of the Child Behavior Scale, a well-validated measure of children’s social and behavioral risk (Ladd &Profilet, 1996; α = .83, for the current sample). Parents reported on their child’s attention problems using nine items from the Attention Problems subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991). Ratings were made on a scale from 1 (Not true) to 3 (Very true or often true). The items showed good internal reliability (α = .74). Teacher- and parent-reports of attention problems were significantly correlated (r = .56p< .001), and, therefore, averaged to create a composite attention problem score.

Procedures

Children and one accompanying parent came individually to the lab. Upon arrival, the study was explained to the parent and child and parental consent and child assent forms were signed. The study consisted of two parts – an eye tracking task and the completion of parent- and child-report questionnaires. Participants were randomly assigned to either complete the eye tracking or the questionnaires first. The parent and child completed the questionnaires in the same room with a research assistant present to insure that they did not discuss or share their answers. The questionnaires took approximately 10 minutes to complete.

For the eye tracking task, children were escorted to a sound-proofed room. Children were seated at a laboratory table and placed their head in the eye-tracker headrest, which was adjusted to make the child comfortable. The eye tracker was then calibrated and validated to ensure gaze position accuracy of 0.50 degrees or better.Children then performed a demonstration task in which they moved a picture across the computer screen with their eyes. This task allowed children to become more comfortable with the eye tracking procedure. Children watched all 60 video clips(i.e., all children watched the boy and girl video clips). Between video clips, children fixated a cross located at the center of the computer screen. No other tasks were performed other than the viewing of the video clips. After completing the eye tracking task and the questionnaires, parents and children were thanked for their participation, and parents were given a $25 honorarium.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. On average, children fixated quickly on the provocateur and victim, making a fixation on these actors prior to the initiation of the provocation. In contrast, on average,children first fixated on the empathic and amused peers after the initiation of the provocation. After the provocation, children spent considerable time attending to the provocateur and victim and relatively less time attending to the empathic or amused peers. Scores on all variables were examined for outliers and skewness. One outlier for post-provocation dwell time on the provocateurwas replaced with a value falling within 3 standard deviations of the mean. Scores for aggressive behavior, attention problems, time until first fixation on the victim, and post-provocation dwell time on the provocateur were corrected for skewness using a square root or log transformation as needed. Correlations and regressions were conducted using these transformed scores.No significant differences in any study variables emerged as a function of the order of the presentation of the video clips.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| M | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggressive behavior | 1.37 | .33 | 1.00 | 2.51 |

| Antisocial peer beliefs | 2.07 | .79 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Prosocial peer beliefs | 2.79 | .70 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Attention problems | 1.40 | .46 | 1.00 | 3.05 |

| Time until first fixation on provocateur | −799.88 | 538.96 | −1697.90 | 940.33 |

| Time until first fixation on victim | −499.98 | 546.22 | −1551.33 | 2103.70 |

| Time until first fixation on empathic peer | 222.17 | 1159.67 | −3128.00 | 3676.00 |

| Time until first fixation on amused peer | 552.60 | 1113.89 | −2239.75 | 4101.20 |

| Post-provocation dwell time on provocateur | 1977.49 | 513.32 | 196.58 | 2956.25 |

| Post-provocation dwell time on victim | 2232.24 | 401.93 | 1292.50 | 3245.42 |

| Post-provocation dwell time on empathic peer | 575.49 | 210.18 | 55.00 | 1000.08 |

| Post-provocation dwell time on amused peer | 549.95 | 155.57 | 134.17 | 840.92 |

Note. All time until first fixation scores were centeredaround the time at which the ambiguous provocation began in each video clip. Negative scores, therefore, indicate first fixations that began prior to the initiation of the ambiguous provocation. Positive scores indicate first fixations that began after the initiation of the ambiguous provocation. All eye tracking data are reported in milliseconds.

Bivariate correlations are presented in Table 2. Aggressive behavior was correlated positively with antisocial peer beliefs and attention problems, and negatively with prosocial peer beliefs. Moreover, aggressive behavior was significantly correlated with time until first fixation on the provocateur and, although more modestly, with time until first fixation on the empathic and amused peers. Aggressive behavior was not correlated with time until first fixation on the victim. Aggressive behavior was negatively correlated with dwell time on the amused peer after the provocation had occurred. Consistent with the notion that antisocial and prosocial peer beliefs represent distinct constructs, the correlation between the two was moderate. Furthermore, antisocial peer beliefs were positively correlated with time until first fixation on the amused peer, and prosocial peer beliefs were negatively correlated with dwell time on the provocateur after the provocation. Attention problems were correlated positively with time until first fixation on the provocateur and negatively with dwell time on the victim after the provocation.As a follow-up, bivariate correlations were computed between aggressive behavior and the eye tracking variables controlling for attention problems. Correlations between aggression and time until first fixation on the provocateur (r = .29, p = .02) and dwell time on the amused peer after the provocation (r = −.30, p = .01) remained significant. The correlations between aggression and time until first fixation on the empathic peer (r = .19, ns) and the amused peer (r = .18, ns) did not change notably in magnitude although they were no longer statistically significant.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Aggressive behavior | --- | ||||||||||

| 2. Antisocial peer beliefs | .39*** | --- | |||||||||

| 3. Prosocial peer beliefs | −.34** | −.49*** | --- | ||||||||

| 4. Attention problems | .41*** | .20† | −.10 | --- | |||||||

| 5. Time until first fixation on provocateur | .35** | .12 | −.12 | .23† | --- | ||||||

| 6. Time until first fixation on victim | .02 | .16 | −.13 | .06 | .22† | --- | |||||

| 7. Time until first fixation on empathic peer | .21† | .00 | −.04 | .08 | .09 | .26* | --- | ||||

| 8. Time until first fixation on amused peer | .20† | .27* | −.11 | .09 | −.01 | .13 | .22† | --- | |||

| 9. Post-provocation dwell time on the provocateur | .05 | .11 | −.24* | −.08 | .27* | .15 | .05 | −.05 | --- | ||

| 10. Post-provocation dwell time on the victim | −.02 | −.12 | −.01 | −.23† | −.17 | −.55*** | −.27* | −.03 | −.33** | --- | |

| 11. Post-provocation dwell time on the empathic peer | −.09 | −.13 | −.01 | −.14 | −.03 | −.29* | −.39*** | −.05 | −.03 | .25* | --- |

| 12. Post-provocation dwell time on the amused peer | −.24* | .03 | .14 | .08 | −.15 | −.05 | −.18 | .23† | −.07 | −.04 | −.01 |

p< .10.

p< .05.

p< .01.

p< .001.

Time until First Fixation on Actors, Aggressive Behavior, and a Focal Mode of Attention

The bivariate correlations indicated that aggression was associated with time until fixation on the provocateur, empathic peer, and amused peer. Analyses were conducted to determine whether this pattern of findings could be attributed to a focal mode of attention. Aggression was negatively associated with the number of fixations children made on the actors prior to the provocation (r = −.25, p = .04). Number of fixations on the actors was also negatively correlated with time until first fixation on the provocateur, victim, empathic peer, and amused peer, rs = −.46, −.29, −.26, and −.21, ps≤ .08. This pattern indicates that aggression was associated with making fewer, but longer, fixations prior to the provocation (i.e., a more focal mode), resulting in greater time until first fixation on the actors. In contrast, lower levels of aggression was associated with a more ambient mode as indicated by many short fixations quickly distributed across all four actors.

Interactive Contribution of Time until First Fixation on the Actors and Peer Beliefs in the Prediction of Aggression

Two series of regression analyses were conducted to examine whether the relation between time until first fixation on the four actors and aggression was moderated by children’s peer beliefs. In the first series, antisocial peer beliefs served as the moderating variable, and in the second series, prosocial peer beliefs served as the moderating variable. All predictors were mean centered, and interactions were decomposed by examining simple slopes at −1, 0, and 1 standard deviations of the moderating variable (Aiken & West, 1991). Results of these regressions can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results from Regression Analyses Predicting Aggression from Time until First Fixation and Peer Beliefs

| Target role |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provocateur |

Victim |

Empathic peer |

Amused peer |

|||||||||

| Predictors | β | CI | R2 | β | CI | R2 | β | CI | R2 | β | CI | R2 |

| Time until first fixation | .26* | [.06, .46] | .30*** | −.04 | [−.27, .17] | .16* | .20† | [.00, .41] | .23** | .11 | [−.12, .34] | .17* |

| Antisocial peer beliefs | .35*** | [.16, .54] | .45*** | [.06, .86] | .39*** | [.20, .58] | .36*** | [.15, .58] | ||||

| Time until first fixation × peer beliefs | .23* | [.03, .43] | .06 | [−.34, .46] | .17 | [−.04, .37] | .01 | [−.21, .24] | ||||

| Time until first fixation | .23* | [.00, .45] | .25** | −.03 | [−.26, .19] | .12† | .18† | [−.02, .35] | .27** | .17 | [−.05, .38] | .15† |

| Prosocial peer beliefs | −.22† | [−.44, .01] | −.45* | [−.86, −.04] | −.29** | [−.49, −.10] | −.33** | [−.54, −.05] | ||||

| Time until first fixation × peer beliefs | −.23† | [−.47, .02] | −.12 | [−.54, .30] | −.34*** | [−.54, −.15] | .02 | [−.20, .24] | ||||

p< .10.

p< .05.

p< .01.

p< .001.

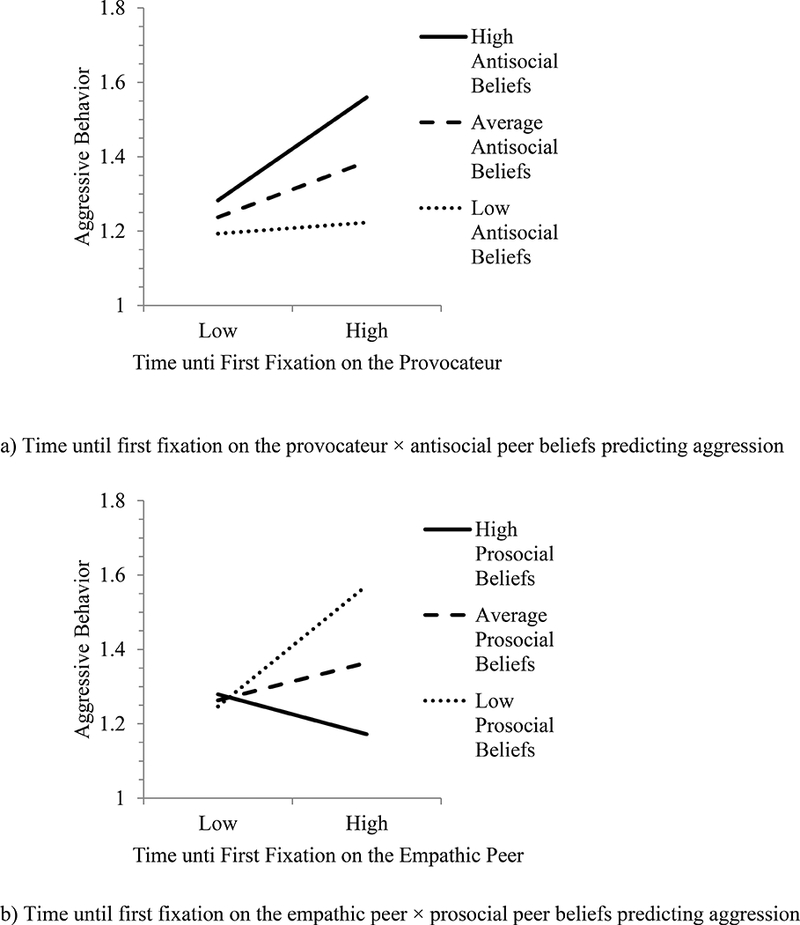

Antisocial peer beliefs positively predicted, and prosocial peer beliefs negatively predicted, aggressive behavior. A main effect for time until first fixation on the provocateur and a time until first fixation on the provocateur ×antisocial peer beliefs interaction emerged (see Figure 2a). Tests of simple slopes revealed that time until first fixation on the provocateur was associated with greater levels of aggression at moderate, b = .006, t(66) = 2.37, p = .02, and high levels of antisocial peer beliefs, b = .011, t(66) = 3.61, p< .001. However, the relation between time until first fixation on the provocateur and aggressive behavior was not significant at low levels of antisocial peer beliefs, b = .00, t(66) =.34, ns. Aggressive behavior was highest at high levels of time until first fixation on the provocateur in combination with high levels of antisocial peer beliefs. At low levels of time until first fixation on the provocateur, children showed little aggression regardless of theirantisocial peer beliefs.The interaction between time until first fixation on the provocateur and prosocial peer beliefs only approached statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Interactive contribution of time until first fixation on the (a) provocateur and antisocial peer beliefs, and (b) empathic peer and prosocial peer beliefs to the prediction of aggression.Estimated values are based on raw aggression scores.

Consistent with the bivariate correlations, time until first fixation on the victim was not predictive of aggression. Furthermore,the time until first fixation on the victim × antisocial peer beliefsand the time until first fixation on the victim × prosocial peer beliefs interactions were nonsignificant.

As anticipated, the interaction between time until first fixation on the empathic peer and antisocial peer beliefs was not significant, but the time until first fixation on the empathic peer × prosocial peer beliefs interaction was (see Figure 2b). Time until first fixation on the empathetic peer was associated with aggressive behavior at low levels of prosocial beliefs, b = .006, t(66) = 3.42, p = .001, but was not significant at moderate, b = .002, t(66) = 1.63, ns, or high levels of prosocial beliefs, b = .00, t(66) = −1.26, ns. Aggressive behavior was highest athigh levels of time until first fixation on the empathic peer in combination with low levels of prosocial peer beliefs.At low levels of time until first fixation on the empathic peer, children showed low levels of aggressive behavior regardless of their prosocial peer beliefs.

Although moderately associated at a bivariate level, time until first fixation on the amused peer was not predictive of aggression, and no interactions with peer beliefs emerged.

Interactive Contribution of Total Dwell Time Post-Provocation and Peer Beliefs in the Prediction of Aggression

Two series of regression analyses were conducted to examine whether the relations between total dwell time post-provocation on the four actors and aggression were moderated by children’s peer beliefs. Results from these regressions can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results from Regression Analyses Predicting Aggression from Post-event Dwell Time and Peer Beliefs

| Target role |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provocateur |

Victim |

Empathic peer |

Amused peer |

|||||||||

| Predictors | β | CI | R2 | β | CI | R2 | β | CI | R2 | β | CI | R2 |

| Post-provocation dwell time | −.02 | [−.24, .20] | .16* | .03 | [−.19, .24] | .16* | −.03 | [−.25, .19] | .16* | −.25* | [−.44, −.05] | .28** |

| Antisocial peer beliefs | .39** | [.19, .59] | .43*** | [.22, .64] | .39*** | [.19, .59] | .40*** | [.21, .58] | ||||

| Post-provocation dwell time × peer beliefs | .07 | [−.15, .29] | .09 | [−.14, .32] | −.04 | [−.25, .18] | −.25** | [−.45, −.06] | ||||

| Post-provocation dwell time | .01 | [−.22, .24] | .13† | −.04 | [−.26, .19] | .12† | −.10 | [−.32, .11] | .15† | −.14 | [−.36, .07] | .20* |

| Prosocial peer beliefs | −.34** | [−.55, −.12] | −.32** | [−.55, −.10] | −.35*** | [−.55, −.15] | −.35*** | [−.55, −.14] | ||||

| Post-provocation dwell time × peer beliefs | −.12 | [−.34, .11] | .06 | [−.19, .30] | .15 | [−.06, .37] | .22* | [.00, .43] | ||||

p< .10.

p< .05.

p< .01.

p< .001

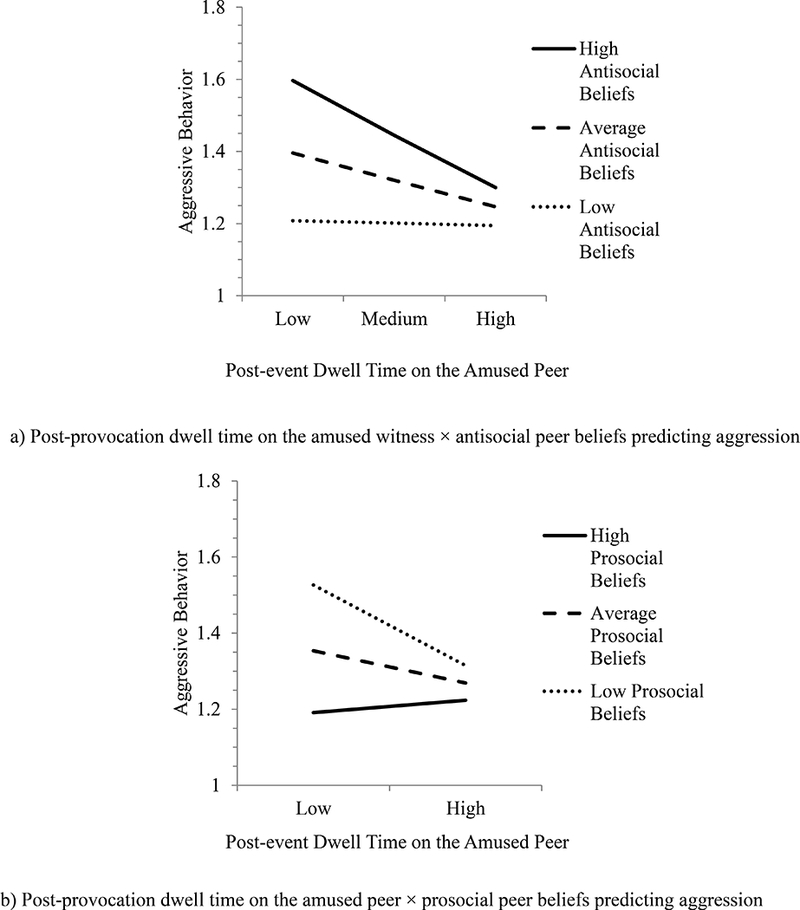

No main or interactive effects of post-provocationdwell time on the provocateur, victim, or empathic peeremerged. There was a main, negative effect of post-provocation dwell time on the amused peer and aggression when antisocial peer beliefs was included in the regression equation. Furthermore, the interactions between post-provocation dwell time on the amused peer and antisocial peer beliefs and between post-provocation dwell time on the amused peer and prosocial peer beliefs were significant. Post-provocation dwell time on the amused peer was negatively associated with aggression at moderate, b = −.02, t(66) = −2.41, p= .02,and high, b = −.04, t(66) = −3.51, p< .001, levels of antisocial peer beliefs, but not at low levels of antisocial peer beliefs, b = .00, t(66) = −.18, ns. Greater attention to the amused peer post-provocation was also associated withless aggressive behavior at low levels of prosocial beliefs, b = −.03,t(66) =−2.55, p =.01. Post-provocation dwell time on the amused peer was not predictive of aggressionat moderate, b = −.01, t(66) = −1.26, ns, or high levels of prosocial beliefs, b = .00t(66) = .34, ns. Graphs of these interactions can be found in Figure 3. At high levels of attention to the amused peer, children evidenced low levels of aggression regardless of their peer beliefs. However, at low levels of attention to the amused peer, children evidencedhigh levels of aggression if they had greater antisocial peer beliefs or lower prosocial peer beliefs and low levels of aggression if they had low antisocial or high prosocial peer beliefs

Figure3.

Interactive contribution of post-provocation dwell time on the amused witness and (a) antisocial peer beliefs and (b) prosocial peer beliefs to the prediction of aggression. Estimated values are based on raw aggression scores.

Discussion

Social interactions are chronological events that often follow a systematic sequence. The findings from the current study underscore the need to take into account these temporal dynamics when investigating the role of attention in aggressive behavior. This was accomplished by having children watch video clips of ambiguous provocation and by examining separately time until fixation on early-occurring cues and attention to cues that occurred later, following the provocation. The resultsprovide evidence that aggression is correlated with time until fixation on social cues (i.e., time until first fixation on the provocateur, empathetic peer, and amused peer),and with suppressed attention (i.e., low levels of attention on the amused peer) after the provocation. This study was also the first to more directly test whether the role of attention in aggressionis contingent upon holding negative social schemas.As predicted, deployment of attention was related to aggression only when children held peer beliefs consistent with a negative interpretation of other’s behavior.Together, these findings provide greater clarity regarding how individual differences in the earliest stages of social information-processing may contribute to aggressive behavior.

Aggressive Behavior and Time until Fixation on Social Cues

The bivariate correlations showed that aggressive behavior was associated positively with the time it took to fixate on the provocateur and, to a lesser extent, the time it took to look at the empathic and amused peers. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown that aggression is related to an inability to remember relevant social information (Dodge et al., 1997; Weiss et al., 1992), particularly information occurring early in a social interaction. However, whether these memory deficits have their roots in insufficient attention being allocated to social cues or problems with the recall ofthis information has been unclear (Horsley et al., 2010; Pettit et al., 2001). By using eye tracking to assess attention, we were able to provide evidence that greater time until fixating on social cues, at least in part, may explain why aggression has been associated with poor recall of those cues.

Moreover, the findings were consistent with the proposition that aggression is associated with a focal mode of attention(i.e., making a relatively small number of long fixations), rather than an ambient mode (i.e., making a relatively large number of short fixations). The more focal mode displayed by aggressive children was associated with increased time until first fixation on the provocateur, amused peer, and empathetic peer. The consequence was missed opportunity to attend to information communicating behavior as non-hostile (e.g., neutral expressions). Horsley et al. (2010) found that making few fixations on relevant stimuli prior to a provocation was associated with poor recall for those cues. Together, these studies suggest that aggressive children may not thoroughly attend to their social environment, at least during early stages of a social interaction, leading to poor recall of relevant information.

Time until first fixationon the provocateur emerged as the strongest correlate of aggression. Children typically attended quickly to the provocateur, with average first fixation times occurring almost 800 ms before the provocation. This may have been due to subtle cuesindicating that the provocateur would be initiating an action (e.g., walking into the scene for the “paint spill” vignette, turning around to face the victim in the “mud” vignette, and standing apart from the other three actors in the “teams” vignette). As more focused attention reduces the likelihood that salient cues will capture attention (Belopolsky et al., 2007), aggressive children’s attention may not have been captured by these subtle cues.As the behavior of the provocateur is likely most essential to devising the intentionality of the provocation, greater time until first fixation on the provocateur may be particularly problematic. Interestingly, the association between delayed attention to the provocateur and aggression remained significant even after controlling for attention problems, suggesting that risk posed by not attending quickly to the provocateur is not limited to children with general attention deficits.

Researchers have long proposed that that the reason inattention to social cues poses a risk for aggression is that it leads to overreliance onpre-existing social schemas, rather than on available information, when responding to ambiguous provocations(Dodge & Tomlin, 1987; Pettit et al., 2001). This study was the first to directly examine social schemas in relation to biases inattention and aggression. As expected, longer time until first fixation on the provocateur was associated with aggression only when children held antisocial views of peers. This finding is consistent with the proposition that in the absence of disconfirming information aggressive children rely on hostile social schemas to interpret an ambiguous provocation. Similarly, longer time until first fixation on the empathic peer was associated with aggression only among those who viewed their peers as low on prosocial traits. If they fail to notice the empathic peer’s earlier, neutral behavior, children low in prosocial peer beliefs may assume that the empathic peer was initiallycomplicit with the provocation. This pattern suggests an interesting specificity in children’s use of social schemas. Whereas antisocial peer beliefs may inform the interpretation of other’s potentially hostile actions, beliefs regarding peers’ prosocial behaviors may be most relevant in interpreting the behavior of witnesses who were not directly involved in the provocation.

Contrary to our hypotheses, peer beliefs did not moderate the relation between time until first fixation on the amused peer and aggression. Children were slowest to look at the amused peer, often not fixating on the amused peer until after the provocation. Thus,top-down processing and social schemas may not have been necessary for understanding the amused peers’ behavior. However,time until first fixation on the amused peer was positively correlated with holding antisocial peer beliefs and moderately correlated with aggression. In accordance with scene perception research (Gordon, 2006; Underwood et al., 2007), the attention of children who view peers as antisocial may have been drawn to cues inconsistent with a hostile interpretation of the ambiguous provocation. The consequence may have beengreater time until first fixationon cues clearly consistent with that interpretation (i.e., the amused peer). In accordance with previous research (Troop-Gordon & Ladd, 2005), antisocial peer beliefs were alsocorrelated with aggression. Thus, rather than moderating the link between delayed attention to the amused peer and aggression, holding antisocial peer beliefs may be the reason why aggression was positively associated with time until first fixation on the amused peer.

Unexpectedly, aggression was not associated with time until first fixation on the victim. If a focal mode is correlated with longer time until first fixation on the victim and with aggression, why would time until first fixation on the victim not also be correlated with aggression? One possibility is that, as was the case for time until first fixation on the provocateur and empathetic peer, whether delayed attention on the victim is associated with aggression depends on having schemas about the victim that would lead to a hostile attribution for the provocation. For example, having a schema that some peers are easy to pick on and engage in behaviors that make them vulnerable to other’s aggression may have moderated the link between time until first fixation on the victim and aggression, such that a delay in attention to the victim may be predictive of aggression when it is combined with a schema that some children act in a manner that elicitspeers’ hostility.

Aggressive Behavior and Selective Attention after the Provocation

It was further anticipated that selective attention after the provocation would be associated with aggression. Specifically, it was expected that aggression would be positively associated with attention to information communicating that the intent was not hostile (i.e., the neutral expression of the provocateur) and would be negatively associated with attention to information consistent with viewing the provocation as hostile (i.e., the amused and empathetic peers). Furthermore, it was anticipated that these biases in attention would be associated with aggression only when children held negative peer beliefs.

Support for these hypotheses was mixed. Spending little time on the amused peer was associated with greater aggression when children held antisocial peer beliefs and when they held low prosocial beliefs. The amused peers’ behavior (i.e., smiling and laughing at the victim) reflected both meanness and a lack of concern for the victim’s distress. Aggressive children’s attention may not be directed to the amused peer because such behavior is consistent with their view of peers as being antisocial and uncaring. These findings are consistent with previous research showing that aggression and anger are negatively associated with attending to information reflecting hostility (Horsley et al., 2010; Wilkowski et al., 2007; Shippell et al., 2003) and extends these earlier findings by providing evidence that inattention to hostile cues is associated with aggression only when children hold negative perceptions of peers.

However, the proposition that attention would be drawn to the schema-inconsistent cue (i.e., the provocateur; Gordon, 2006; Underwood et al., 2007) was not supported. It is possible that the neutral expression displayed by the provocateur was not salient enough, or sufficiently inconsistent with a hostile attribution of the scene, to capture attention. Unfortunately, a more benign cue from the provocateur (e.g., shock that the victim had been hurt) would have changed the nature of the provocation from one in which the provocateur’s intention was ambiguous to one in which the provocation was clearly unintentional. In addition, there was no support for the hypothesis that aggression would be associated with inattention to the empathetic peer after the provocation. It is possible that children varied in how they perceived the empathic peers. Although some may have perceived the empathetic peers as affirmation that the provocation was intentionally hostile, others may have interpreted them as communicating concern (i.e., others are not hostile to the victim). Thus, children’s attention on the amused peer may have been equally likely for those low and high in aggression. However, this explanation is speculative. Further research is needed in which children’s interpretations of the actors’ behavior is assessed.

Implications for Intervention

Numerous programs aimed at reducing aggression by ameliorating maladaptive patterns of social information processing have been conducted with positive results (Dodge, Godwin, & The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2013). The current findings speak to the potential of adding to these programs training onhow to effectively attend to the social environment. Investigators have increasingly utilized attentional retraining programs in the treatment of disorders, albeit the preponderance of this work has focused on internalizing problems (Cowart &Ollendick, 2010; Hazen, Vasey, & Schmidt, 2009; Schmidt, Richey, Buckner, &Timpano, 2009). Similar attentional retraining techniques may be effectual in increasing attention to relevant cues among aggressive youth.

The findings also suggest that aggressive behavior may be reduced by targeting the underlying beliefs that,in conjunction with patterns of attention, support aggression. Unfortunately, these peer beliefs do not develop in a vacuum, but rather can result from chronic friendlessness and peer victimization (Ladd & Troop-Gordon, 2003). Although some aggressive youth are socially skilled and popular (Hawley, 2003), for those whose aggression stems from stressful peer relationships and reacting negatively to perceived provocations, efforts to improve their relationships may lead to positive shifts in peer schemas. The result may be more positive responses to ambiguous provocations, even if changes are not made to attention to social cues.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study had a number of strengths including using eye tracking and video clips to measure attention toprovocations unfolding in real time. An additional strength was the use of multiple informants to assess aggression. However, research isneeded to address limitations in this study. Most notably, data came from a larger protocol in which children watched video clips passively without providing their thoughts or interpretations of the scenes. The advantage of this strategy was that participants’ eye movements were not unduly influenced by explicit questions regarding their understanding of, or reactions to, the video clips. The unfortunate consequence is that direct links between attention, peer beliefs, and intent attributions cannot be drawn. Furthermore, attributional biases have been linked to reactive, but not proactive, aggression (Crick & Dodge, 1996; Dodge &Coie, 1987; Hubbard, Dodge, Cillessen, Coie, & Schwartz, 2001). The patterns of attention found in this study, therefore, should also be specific toreactive aggression. Indeed, suppressed attention in the Schippell et al. (2003) study and encoding errors in the Dodge et al. (1997) study were associated with reactive, but not proactive aggression. Thus, future studies on biases in attention should take into account these subtypes of aggression.

Some methodological considerations may have also affected the results. In addition to the scenes of ambiguous provocation, children watched scenes depicting prosocial behavior and explicitly aggressive behavior. These video clips may have primed prosocial or antisocial peer schemas. Testing attention to the ambiguous scenes alone would provide a more stringent test of the extent to which pre-existing peer beliefs interact with attention deployment in the prediction of aggression. Attention to cues in the explicitly aggressive video clips will also be of interest. It should further be noted that video clips were observed from a third-person perspective. Although this is similar to the procedures used in previous research on attention to and recall of social cues (e.g., Dodge et al., 1997; Weiss, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1992; Wilkowski et al., 2007), SIP may most strongly be tied to aggression when provocation is directed at the participant (Dodge & Frame, 1982). Thus, research in this area could be improved by assessing attention to social cues when the participant is the target of the provocation.

Although this study’s sample size was comparable to those used in previous research (e.g., Horsley et al., 2010) and was adequate for detecting moderate effects (89% power for identifying significant predictors in a multiple regression), it was not sufficient for detecting small effects, and there was not sufficient power for testing additional moderators. Investigators have begun examining differences in the social contexts that elicit aggressogenic thought patterns among boys and girls (e.g., Crick, Grotpeter, &Bigbee, 2002; Mathieson et al., 2011). It is possible that associations between attentionto ambiguous provocations and aggression differ as a function of the gender of the participant, gender of the actors in the scene, and the nature of the depicted provocation (i.e., physical versus verbal). Testing for such differences will be an important avenue for future research. Furthermore, the children participating in this study were rather homogenous with regard to ethnicity and socio-economic status. It will be important to see whether these findings generalize to more diverse populations.

Conclusion

How attention is deployed when observing others’ behavior may set the stage for subsequent maladaptive processing of information and aggressive behavior. Some children may engage in a focal mode of attention during the early processing of an ambiguous provocation leading to greater time until fixation on relevant cues. This lack of attention to relevant cues presented early in a social scene, when combined with negative social schemas, may be particularly culpable in eliciting aggressive responses to provocation. Furthermore, in contrast to claims that aggressive children are hypervigilant to hostile cues, the current findings support the notion that aggression is associated with a suppressed attention to hostile cues. Thus, children who respond aggressively to perceived provocations may benefit from learning to attend to, not away from, potential sources of threat and to use available social cues, not assumptions of others’ behavior, when reacting to their social environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the school administrators, teachers, parents, and children who participated in this project.

Funding

This research was supported by NIH P20 GM103505. The National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) is a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The contents of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official views of the NIH or NIGMS.

Appendix A

Descriptions of video clips depicting ambiguous provocation. Each clip was acted out by four boy actors and four girl actors. The faces of all actors were visible in the scene. Times when the ambiguous provocation occurred and total duration of the video clip are noted for the boy and girl videos, respectively.

Ball hit.

Actorsbegin the scene standing in a semi-circle (from left to right: victim, empathic peer, amused peer, provocateur). The children toss a basketball for a total of six throws. All children maintain a neutral face during these throws. The victim turns to look off screen. The provocateur throws the ball which hits the victim in the arm (provocation occurs at 5960 ms and 7000 ms). The victim winces in pain. The empathic peer looks at the victim with a concerned expression. The amused peer looks at the victim and laughs inaudibly. The provocateur maintains a neutral expression (total clip duration: 9000 ms and 10320 ms).

Trip.

Actors begin the scene sitting in four desks situated in two rows (From left to right, front row: provocateur, empathic peer; back row: victim, amused peer). All four actors are staring at their desks with neutral expressions. The victim stands and begins to walk forward at the same time that the provocateur stretches a leg. The victim then trips on the provocateur’s leg and falls to the floor (provocation occurs at 2880 ms and 3480 ms). The victim’s physical expression shows pain. The provocateur maintains a neutral expression. The empathic peer looks at the victim with concern, and the amused peer looks at the victim and laughs inaudibly (total clip duration: 8160 ms and 8199).

Spilled paint.

The provocateur begins the scene standing to the left of the screen. Four desks are situated in two rows. In the front row sits the empathic peer on the left and the amused peer on the right. In the second row, there is an empty desk on the left and the victim is on the right. The empathic and amused peer are writing on paper. The victim is working with a paint brush and a cup, presumably filled with paint. The provocateur walks to the empty desk with a neutral expression and while sitting down knocks the cup over with an arm (provocation occurs at 4200ms and 3720 ms). The victim stands up quickly and in a whiny voice says, “My project.” The provocateur sits down and looks at the paper on the desk. The empathic peer turns and looks at the victim with concern. The amused peer turns around and laughs inaudibly (total clip duration: 9240 ms and 6880 ms).

Lunch table.

Three actors begin the scene sitting at a small table with lunch bags and food containers (from left to right: the amused peer, the provocateur, and the empathic peer). The victim is standing to the right of the table. The table is cluttered, and there are no more chairs. However, there is enough room on the table for one more lunch bag. The provocateur looks at the victim and in a neutral tonesays, “There’s no more room at this table” (provocation occurs at 2040 ms and 4000 ms). The amused peer smirks and laughs inaudibly. The empathic peer looks apologetically at the victim. The victim says, “Can you move over?” The provocateur says in a neutral tone, “There isn’t enough room.” The victim responds, “I need to sit somewhere.” The amused peer continues to smirk and laugh inaudibly. The empathic peer continues to look apologetic. The victim looks sad. (total clip duration: 9840 ms and 11520 ms).

Teams.

The four actors begin the scene standing in a row (from left to right: the provocateur, the amused peer, the empathic peer, and the victim). The provocateur is holding a basketball facing the other three actors. The provocateur says in a neutral tone, “Logan and Jordan, you can be on my team” (provocation occurs at 2880 ms and 2800 ms). The amused and empathic peers move to the other side of the provocateur and look at the victim. The victim says, “Wait. I’m not on a team.” The amused peer points at the victim and laughs inaudibly. The empathic peer looks apologetically at the victim. The provocateur says, “Sorry, Chris. The teams are even now. You’ll have to sit this one out.” The amused peer continues to smile, and the empathic peer continues look sorry as the victim says, “Can I play next time?” The provocateur shrugs as the amused peer smirks and the empathic peer looks at the victim with an apologetic expression. (total clip duration: 11360 ms and 13400 ms).

Mud.

The four actors begin the scene standing in a row (from left to right: the amused peer, the provocateur, the victim, and the empathic peer). The victim has his back to the provocateur and is talking to the empathic peer. The provocateur turns and taps the victim on the back and with a neutral tone and facial expression says, “Hey, Jessie. Did you get mud on your shirt?” (provocation occurs at 3080 ms and 4000 ms). The amused peer smiles and laughs inaudibly. The empathic peer looks concerned for the victim. Theyamused and empathic peers maintain these expressions throughout the remainder of the clip. The victim sounding concerned says, “What do you mean?” The provocateur says, “I was just asking,” and the victim says, “I don’t know. I can’t see it” in a confused, somewhat embarrassed voice. (total clip duration: 9120 ms and 10760 ms).

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L & West S (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Belopolsky AV, Zwaan L, Theeuwes J, & Kramer AF (2007). The size of attentional widow modulates attentional capture by color singletons. Pychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14, 934–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowker JC, Rubin KH, Buskirk-Cohen A, Rose-Krasnor L, & Booth-LaForce C (2010). Behavioral changes predicting temporal changes in perceived popular status. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31, 126–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broidy LM, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE, Bates JE, Brame B, et al. (2003). Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six-site, cross-national study. Developmental Psychology, 39, 222–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Cairns BD, &Neckerman HJ (1989). Early school dropout: Configurations and determinants. Child Development, 60, 1437–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowart MJW, &Ollendick TH (2010). Attentional biases in children: Implications for treatment In Hadwin JA& Field AP (Eds.), Information processing biases and anxiety: A developmental perspective (pp. 297–319). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR (1995). Relational aggression: The role of intent attributions, feelings of distress, and provocation type. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Dodge KA (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Dodge KA (1996). Social information-processing mechanisms on reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development, 67, 993–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR,Grotpeter JK, &Bigbee MA (2002). Relationally and physically aggressive children’s intent attributions and feelings of distress for relational and instrumental peer provocations. Child Development, 73, 1134–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, &Coie JD (1987). Social-information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1146–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, & Frame CL (1982). Social cognitive biases and deficits in aggressive boys. Child Development, 53, 620–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Godwin J, & The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (2013). Social-information-processing patterns mediate the impact of preventative intervention on adolescent antisocial behavior. Psychological Science, 24, 456–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Lochman JE, Harnish JD, Bates JE, & Pettit GS (1997). Reactive and proactive aggression in school children and psychiatrically impaired chronically assaultive youth. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, & Newman JP (1981). Biased decision-making processes in aggressiveboys.Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90, 375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, & Price JM (1994). On relation between social information processing and socially competent behavior in early school-aged children. Child Development, 65, 1385–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, & Tomlin AM (1987). Utilization of self-schemas as a mechanism of interpretational bias in aggressive children. Social Cognition, 5, 280–300. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald PD, & Asher SR (1987, August). Aggressive-rejected children’s attributional biases about liked and disliked peers. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RD (2006). Selective attention during scene perception: Evidence from negative priming. Memory & Cognition, 34, 1484–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouze KR (1987). Attention and social problem solving as correlated of aggression in preschool males. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 15, 181–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley PH (2003). Prosocial and coercive configurations of resource control in early adolescence: A case for the well-adapted Machiavellian. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 279–309. [Google Scholar]

- Hazen RA, Vasey MW, & Schmidt NB (2009). Attentional retraining: A randomized clinical trial for pathological worry. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43, 627–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley TA, de Castro BO, & Van der Schoot M (2010). In the eye of the beholder: Eye-trackingassessment of social information processing in aggressive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 587–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JA, Dodge KA, Cillessen AHN, Coie JD, & Schwartz D (2001). The dyadic nature of social information processing in boys’ reactive and proactive aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 268–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokko K, &Pulkkinen L (2000). Aggression in childhood and long-term unemployment in adulthood: A cycle of maladaptation and some protective factors. Developmental Psychology, 36, 463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, &Kochenderfer-Ladd B (2002). Identifying victims of peer aggression from early to middle childhood: Analysis of cross-informant data for concordance, estimation of relational adjustment, prevalence of victimization, and characteristics of identified victims. Psychological Assessment, 14, 74–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, &Profilet SM (1996). The Child Behavior Scale: A teacher-report measure of young children’s aggressive, withdrawn, and prosocial behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 32, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, & Troop-Gordon W (2003). The role of chronic peer difficulties in the development of children’s psychological adjustment problems. Child Development ,74, 1344–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, & Hay D (1997). Key issues in the development of aggression and violence from childhood to early adulthood. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 371–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon-Lewis C, Rabiner D, & Starnes R (1999). Predicting boys’ social acceptance and aggression: The role of mother-child interactions and boys’ beliefs and peers. Developmental Psychology, 35, 632–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson LC, Murray-Close D, Crick NR, Woods KE, Zimmer-Gembeck M, Geiger TC, Morales JR (2011). Hostile intent attributions and relational aggression: The moderating roles of emotional sensitivity, gender, and victimization. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 977–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Mennin DS, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2011). Emotional dysregulation and adolescent psychopathology. A prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 544–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milich R, & Dodge KA (1984). Social information processing in child psychiatric populations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 12, 471–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannasch S, Helmert JR, Roth KAK, Herbold A, & Walter H (2008). Visual fixation durations and saccade amplitudes: Shifting relationship in a variety of conditions. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Polaha JA, & Mize J (2001). Perceptual and attributional processes in aggression and conduct problems In Hill J & Maughan B (Eds.), Conduct disorders in childhood and adolescence (pp. 292–319). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner DL, Keane SP, & MacKinnon-Lewis C (1993). Children’s beliefs about familiar and unfamiliar peers in relation to their sociometric status. Developmental Psychology, 29, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Raine A (2005). The interaction of biological and social measures in the explanation of antisocial and violent behavior In Stoff DM& Susman EJ(Eds.), Developmental psychobiology and aggression (pp. 13–42). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, & Swenson LP (2009). Do perceived popular adolescents who aggress against others experience adjustment problems themselves? Developmental Psychology, 45, 868–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, &Krasnor LR (1986). Social-cognitive and social behavioral perspectives on problem solving In Perlmutter M (Ed.), The Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology (Vol. 18, pp. 1–68). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli C, Ojanen T, Haanpää J, &Peets K (2005). ‘I’m OK but you’re not’ and other peer-relational schemas: Explaining individual differences in children’s social goals. Developmental Psychology, 41, 363–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]