Abstract

Huntington's disease (HD) is a dominant neurodegenerative disease caused by polyglutamine (polyQ) expansion in the protein huntingtin (htt). HD pathogenesis appears to involve the production of mutated N-terminal htt, cytoplasmic and nuclear aggregation of htt, and abnormal activity of htt interactor proteins essential to neuronal survival. Before cell death, neuronal dysfunction may be an important step of HD pathogenesis. To explore polyQ-mediated neuronal toxicity, we expressed the first 57 amino acids of human htt containing normal [19 Gln residues (Glns)] and expanded (88 or 128 Glns) polyQ fused to fluorescent marker proteins in the six touch receptor neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. Expanded polyQ produced touch insensitivity in young adults. Noticeably, only 28 ± 6% of animals with 128 Glns were touch sensitive in the tail, as mediated by the PLM neurons. Similar perinuclear deposits and faint nuclear accumulation of fusion proteins with 19, 88, and 128 Glns were observed. In contrast, significant deposits and morphological abnormalities in PLM cell axons were observed with expanded polyQ (128 Glns) and partially correlated with touch insensitivity. PLM cell death was not detected in young or old adults. These animals indicate that significant neuronal dysfunction without cell death may be induced by expanded polyQ and may correlate with axonal insults, and not cell body aggregates. These animals also provide a suitable model to perform in vivo suppression of polyQ-mediated neuronal dysfunction.

Huntington's disease (HD) is a dominant neurodegenerative disorder clinically characterized by a decline in psychological, motor, and cognitive abilities (1), and it is caused by the presence of a CAG expansion, encoding expanded polyglutamines (polyQs), in the first exon of the huntingtin (htt) gene (2). HD results in selective neuronal loss within the basal ganglia, notably within the striatum and various cortical areas (3). The polyQ size in HD patients is inversely correlated with the age of onset and severity of symptoms (1). Htt is a ubiquitously expressed and predominantly cytosolic protein of unknown function (2, 4) that may be required for neurogenesis during development (5–7) and for neuronal function and survival in the adult brain (8). The pathogenesis of HD and other inherited polyQ neurodegenerative diseases remains unclear (9). Neuronal loss in HD appears to be initiated by the production of N-terminal fragments of polyQ-expanded htt, presumably by proteolysis (10, 11), with subsequent formation of neuronal intranuclear inclusions (NIIs) (4).

One aspect of polyQ neuronal toxicity is the relationship between NIIs, cell death, and neurological symptoms. In transgenic mice that express the htt exon 1 product (12), the appearance of NIIs containing truncated polyQ-expanded htt before the onset of neurological symptoms has suggested that NIIs may be toxic to neurons (13). However, in a cellular model for HD, the translocation of soluble polyQ-expanded htt cleavage products in the nucleus is required to produce neuronal death, and NIIs appears to result from a protective cell response to sequester toxic soluble polyQ peptides (14). Examination of human HD brain tissue (15, 16) and transgenic mice expressing full-length htt (17–19) has also suggested that NIIs may not be essential to cell death.

Another aspect of polyQ neuronal toxicity is the relationship between aggregation, neuronal dysfunction before cell death, and neurological symptoms. From a phenomenological standpoint, studies of transgenic mice expressing htt exon 1 product (12, 20), and truncated (21, 22) and full-length (17, 19) htt have suggested that neuronal dysfunction (as inferred from electrophysiological abnormalities or behavioral phenotypes) might precede the neuronal death observed in these models. A similar observation was reported for transgenic mice that express polyQ alone under the control of the androgen receptor and show no neuronal death (23). In these studies, a correlation between neuronal dysfunction and formation of NIIs or neuritic aggregates was not consistently reported. However, a putative link with neuropil aggregates was suggested by mice reported to show aggregates in neurites (20–22). The examination of human HD brain from patients with of low-grade striatal pathology has also suggested that abnormal neuropil may be involved (24). Hence, it is possible that polyQ diseases pathogenesis involves alternative or additional components to cell death and NIIs. From a molecular standpoint, a primary mechanism of polyQ neuronal toxicity is likely to be the appearance of misfolded truncated htt species (25), and there is increasing evidence that mutant polyQ proteins interact inappropriately with several proteins required for neuronal survival. For instance, the sequestration of transcriptional coactivators such as CREB-binding protein (CBP) (26) or CA150 (27) may be involved in the pathogenesis of HD, and decreased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene transcription and production by cortical neurons may result in insufficient support of striatal neurons (28). Besides transcription factors, misfolded htt may also interact inappropriately with proteins involved in axonal transport and neurotransmitter uptake and release, leading to their relocalization (29) or dysfunction (30, 31). Altogether, the above-mentioned studies suggest that understanding the relationship between neuronal dysfunction, NIIs, and neuropil aggregates is likely to provide important clues into HD pathogenesis.

Simple model organisms may provide a convenient setting in which to manipulate and decipher polyQ-mediated neuronal dysfunction and neuropil abnormalities as candidate components of HD pathogenesis. We expressed the first 57 amino acids of human htt with normal and expanded polyQ fused to a fluorescent protein marker in Caenorhabditis elegans touch receptor neurons by using the mec-3 promoter (Pmec-3). Pmec-3 is active in 10 neurons including the six touch receptor neurons (AVM, ALML, ALMR, PVM, PLML, and PLMR) needed for gentle touch (32). Because C. elegans does not appear to contain a htt homolog nor long polyQ tracts (33), transgenic phenotypes in worms can be attributed to polyQ transgenes. A significant mechanosensory defective (Mec) phenotype at the tail was correlated with an increased polyQ expansion. Perinuclear protein accumulation was observed in tail mechanosensory neurons, the PLM cells, but did not correlate with polyQ length or the Mec phenotype. Animals expressing 128 Gln residues (Glns) were strongly Mec at the tail and more likely to have aggregates in PLM neuronal processes. Most notably, PLM neuronal processes in these animals also displayed morphological abnormalities, and neuronal dysfunction occurred in the absence of cell death.

These animals indicate that significant neuronal dysfunction without cell death is a phenotype that can be induced in vivo by expanded polyQ. Importantly, these animals also indicate that polyQ-mediated neuronal dysfunction is independent of cell body aggregates and partially correlates with aggregation in neuronal processes and abnormal morphology of axons. Additionally, C. elegans amenability to genetic and pharmacological analyses may uncover aspects of polyQ toxicity difficult to manipulate in vivo by other means, and the availability of highly penetrant neuronal dysfunction without cell death in C. elegans provides a unique model suitable in suppressor screens.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Constructs.

Pmec-3 from plasmid TU1 (Martin Chalfie, Columbia University, New York) was cloned into the HindIII/SalI sites of the green fluorescence protein (GFP) vector pPD95.67. The various length human htt constructs were subsequently cloned into the SalI/BamHI site of the Pmec-3 construct to create Pmec-3htt57Q(19, 88, or 128)∷GFP constructs. The htt57Q19 and htt57Q88 constructs were derived from IT-15 constructs (Christopher Ross, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore) and the htt57Q128 construct was derived from pGBT9 plasmids containing 128 Glns (Centre for Molecular Medicine and Therapeutics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver). To make cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) constructs, GFP was removed through NcoI/ApaI digestion and replaced with the CFP containing NcoI/ApaI fragment from plasmid L3560. The mec-7 promoter (Pmec-7) yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) construct was generated by replacing the GFP containing NcoI/EcoRI fragment of L3691 with the YFP containing NcoI/EcoRI fragment of L4817. All constructs were sequenced to verify integrity. The pPD95.67, L3560, L3691, and L4817 plasmids were gifts from Andy Fire (Washington University, St. Louis).

C. elegans Protocols.

Nematode strains were received from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (St. Paul, MN). Nematodes were maintained following standard methods (34). Transgenic animals were generated by standard transformation techniques (35). The various GFP, CFP, and YFP plasmids were coinjected with a wild-type lin-15 marker plasmid into the gonads of young, adult lin-15 (n765) hermaphrodites. Concentrations used were 50 ng/μl for each test plasmid and 50 ng/μl for the transformation marker plasmid. Pmec-7YFP was injected at a concentration of 15 ng/μl. Four to five independently established transgenic lines per injected DNA pool were selected on the basis of strong lin-15 rescue and comparable fluorescence signals.

Mechanosensory Assays.

To minimize adaptive touch effects, 20–30 animals were transferred to fresh plates 24 h before testing. For each transgenic strain, 200 animals were scored by touching them with a fine hair. Tests included scoring for touch sensitivity at the anterior (head), posterior (tail), or both. Ordinarily, the animals responded by backing away from the touch. Animals were separately scored as either anterior or posterior mechanosensory defective if they failed to respond to a light touch at the appropriate area. A separate test consisted of touching 50 animals of each genotype five times at the anterior and five times at the posterior (36). The responses were recorded for every animal such that, for example, 7 of 10 responses is given as 70% responsiveness.

Cell Death Assays.

Young adult hermaphrodites were examined for PLM cell death through visual inspection under Nomarski microscopy and absence of acridine orange (AO) staining (37, 38).

Morphological Examination.

Pmec-7YFP, Pmec-3htt57Q19∷CFP/ Pmec-7YFP, and Pmec-3htt57Q128∷CFP/Pmec-7YFP animals were examined for PLM neuron morphological abnormalities and the presence of aggregates in neuronal processes. A minimum of 100 animals of each type was scored for the presence of aggregates in PLM neurons and for whether the neurons appeared normal or abnormal.

Fluorescence Microscopy.

Animals were placed into a drop of 2 mM levamisole in M9 (22 mM KH2PO4/22 mM Na2HPO4/85 mM NaCl/1 mM MgSO4) buffer and mounted onto slides containing solidified pads of 3% agarose in M9 buffer. Animals were examined with a Zeiss Axioscope epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Sensys (Photometrics, Tuscon, AZ) charge-coupled device camera and IP Lab software (Fairfax, VA) by using filter sets for GFP, CFP, and YFP. Propidium iodide staining was visualized by using filter for Texas red. AO staining was visualized by using filters for FITC.

Confocal Microscopy.

Animals were incubated in 150 ng/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) in ethanol for 30 min, followed by a 30-min rehydration in M9 buffer. Worms were then briefly incubated in levamisole and mounted as described above. Confocal sections of 0.4 μm were taken of signals surrounding the nucleus, as detected by DAPI staining, by using UV and FITC filters for DAPI and GFP, respectively. The analysis was conducted on a Zeiss Axioscope and visualized on a Bio-Rad Radiance Plus system. ADOBE PHOTOSHOP 5.0 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA) was used for pseudocoloration of images and overlays.

Results

Htt57Q128∷GFP Causes Highly Penetrant Mechanosensory Defect at the Tail.

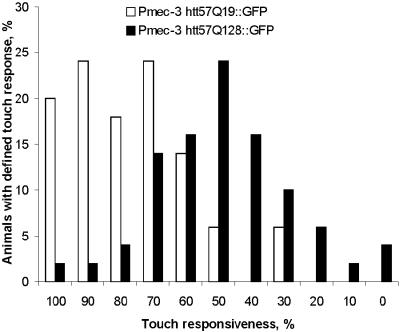

A posterior Mec phenotype is defined as touch-insensitive at the tail. An anterior Mec phenotype is defined as touch-insensitive at the head. Wild-type (N2), Pmec-3GFP, and Pmec-3htt57Q19∷GFP animals were essentially touch sensitive at the tail (Table 1). In contrast, Pmec-3htt57Q88∷GFP animals showed significant and variable posterior touch insensitivity. Posterior touch insensitivity was highly penetrant in Pmec-3htt57Q128∷GFP animals (Table 1). Anterior touch sensitivity was also assessed in transgenic animals, and a mild but significant Mec phenotype was induced by 128 Glns (Table 1). To better assess the polyQ-dependent differences in touch responsiveness, Pmec-3htt57Q19∷GFP and Pmec-3htt57Q128∷GFP animals were challenged with multiple mechanosensory stimuli (Fig. 1). The strains displayed distinct touch responsiveness, which appears suitable in screens for genetic suppression of the Mec phenotype induced by 128 Glns. The penetrance of the Mec phenotype correlated with the level of GFP signals because we have also obtained transgenic lines for 128 Glns that showed a weak GFP signal and that were not Mec. The low standard deviation of Mec animals that express 128 Glns (6%; see Table 1) suggests low animal-to-animal variability for all transgenic lines. Touch tests have been repeatedly performed with the same transgenic lines (128 Glns) maintained over a period of several months. The penetrance of the Mec phenotype at the tail has always been in the same range (data not shown), suggesting stability of the polyQ stretch in trangenic animals.

Table 1.

Expanded polyQ impairs mechanosensation

| Constructs (no. of lines) | Posterior Mec, % | Anterior Mec, % |

|---|---|---|

| N2 (1) | 4 ± 5 | 2 ± 0.3 |

| Pmec–3GFP (5) | 10 ± 1 | ND |

| Pmec–3htt57Q19∷GFP (8) | 11 ± 3 | 8 ± 5 |

| Pmec–3htt57Q88∷GFP (5) | 46 ± 15* | ND |

| Pmec–3htt57Q128∷GFP (9) | 72 ± 6*† | 18 ± 1* |

Posterior and anterior Mec phenotypes are shown as a percentage for each genotype. Results for trials are the mean ± SD. ND, not determined.

Significantly different from Q19 (P < 0.001).

Significantly different from Q88 (P < 0.001). ANOVA tests were used.

Figure 1.

Mec response of individual animals with Pmec-3htt57Q19∷GFP and Pmec-3htt57Q128∷GFP. Ten consecutive mechanosensory responses, five anterior and five posterior, were recorded from 50 individuals of each genotype. The responses were recorded for every animal such that, for example, 3 of 10 responses is given as 30% responsiveness on the x axis (see Materials and Methods).

Normal and Expanded PolyQ Leads to the Accumulation of Fusion Proteins in Touch Receptor Neurons.

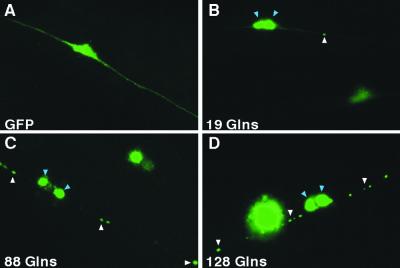

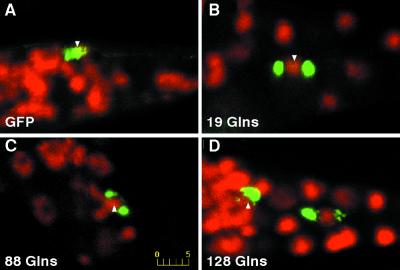

To test for a correlation between posterior Mec phenotypes in transgenic animals and accumulation of transgene products, we examined the expression patterns of GFP fusion proteins in PLM neurons at the young adult stage. Transgenic Pmec-3 GFP lines displayed diffuse signal throughout the nucleus, cell body, and processes (Figs. 2A and 3A). Transgenic lines with a normal polyQ tract (Pmec-3htt57Q19∷GFP) showed accumulation of GFP signal, typically visible as two clusters, apparently surrounding the nucleus (Figs. 2B and 3B). Diffuse expression was also observed throughout the nucleus (Fig. 2B) and along the neuronal processes, with rare accumulation of fusion protein (Fig. 2B). Also, a very weak accumulation was detected in the nucleus (Fig. 3B). The most likely explanation for the accumulation of GFP fusion proteins with a normal polyQ in PLM cells is that accumulation depends on the expression level, length of the carrier protein, and cell types. In Pmec-3htt57Q88∷GFP animals, accumulation of fusion protein around the nucleus was similar to that of Pmec-3htt57Q19∷GFP animals (Figs. 2C and 3C). A weak signal was also detected in the nucleus. Interestingly, several aggregates were often seen along neuronal processes (Fig. 2C). In contrast to Pmec-3htt57Q19∷GFP, diffuse expression was not detected with 88 Glns (Fig. 2C). Pmec-3htt57Q128∷GFP animals also showed accumulations around the nucleus (Fig. 3D). As was the case in Pmec-3htt57Q88∷GFP, a diffuse GFP signal was not detected along neuronal processes. Noticeably, there tended to be a greater number of aggregates along Pmec-3htt57Q128∷GFP processes (Fig. 2D). We conclude that, although polyQ fusion proteins accumulate in PLM cell bodies, there was no significant correlation with polyQ length. In addition, Pmec-3htt57Q19∷GFP lines were wild-type touch sensitive, suggesting no correlation of the Mec phenotypes detected with the accumulation of GFP fusion proteins in the cell body. Rather, Mec phenotypes induced by expanded polyQ appeared to correlate with the accumulation of GFP fusions along PLM cell processes. Cursory examination of L1–L2 larvae expressing 19 or 128 Glns showed limited accumulation of GFP fusion proteins (data not shown), suggesting that accumulation of GFP fusions in transgenic animals may be a progressive phenomenon.

Figure 2.

Expression of GFP fusions in PLM neurons of young adults. Observations were made under a ×100 objective. Posterior is to the right in all cases. Out-of-focus GFP signal in corner of B–D is from the other PLM cell of the animals. (A) Pmec-3GFP. GFP is expressed diffusely throughout the nucleus, cell body, and processes. (B) Pmec-3htt57Q19∷GFP. GFP accumulates as two perinuclear clusters (blue arrows), with diffuse nuclear expression. Diffuse expression is detected along processes with rare cytoplasmic aggregation (white arrow). (C) Pmec-3htt57Q88∷GFP. GFP forms perinuclear accumulations (blue arrows). Unlike PLMs in Pmec-3htt57Q19∷GFP animals, cytoplasmic aggregates along processes are commonly observed (white arrows). (D) Pmec-3htt57Q128∷GFP. GFP forms perinuclear accumulations (blue arrows). PLM neurons have a greater number of aggregates along their processes (white arrows) in comparison to C.

Figure 3.

Confocal analysis of GFP fusions in PLM neurons of young adults. DAPI staining is pseudocolored red, with GFP green. Shown here are reconstructions of z-series, where yellow indicates colocalization of DAPI and GFP signals. Posterior is to the right in all cases. (A) Pmec-3GFP. Diffuse GFP signal is apparent along axonal projections, throughout the cell body, and in the nucleus (arrow). (B) Pmec-3htt57Q19∷GFP. GFP signal shows accumulation around either side of the nucleus, with a faint signal also present within (arrow). (C) Pmec-3htt57Q88∷GFP. GFP signal shows accumulation around either side of the nucleus, with a faint signal also detected inside (arrow). (D) Pmec-3htt57Q128∷GFP. Both PLM nuclei are visible. GFP signal shows accumulation around the nucleus. On the left, a faint signal is detected in the nucleus (arrow), but not in the nucleus on the right. (Scale bar in C is 5 μm and is the same in the other panels.)

PLM Cell Expressing 128 Glns Show Morphological Abnormalities in Their Neuronal Processes.

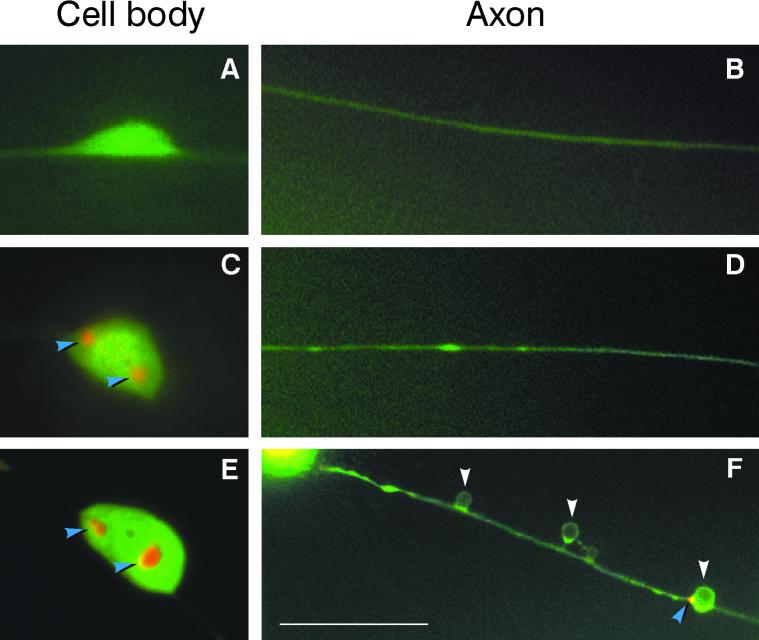

To further examine polyQ-dependent modification of PLM cell processes, transgenic animals were constructed by expressing Pmec-3htt57Q(19 or 128)∷CFP along with Pmec-7YFP. Pmec-7 is the C. elegans promoter for β-tubulin, is active in several neurons including the six touch receptor neurons, and served as a marker to assess neuronal morphological integrity (39). The expression of YFP and accumulation of CFP fusions was observed in PLM cells of animals expressing normal (19 Glns) or expanded (128 Glns) polyQ (Fig. 4). The Pmec-3htt57Q19∷CFP and Pmec-3htt57Q128∷CFP animals (Fig. 4 C–F) showed a more accurate pattern of dual signals in the cell body as compared with GFP fusions (Fig. 2 B and D). This is likely to reflect a difference in the relative intensity levels between GFP and CFP signals. The CFP signal is weaker than GFP, and with the reduction in background signal, it allowed for higher resolution of protein fusions signals.

Figure 4.

Morphology of PLM neurons in young adult transgenic animals expressing CFP and/or YFP fusions. CFP is pseudocolored red; YFP is pseudocolored green. The most frequent phenotypes oberved in each trangenic line are shown (see Table 2). Observations were made under a ×100 objective. Scale bar in F is 5 μm and is the same in the other panels. Anterior is to the right in all cases. (A) Pmec-7YFP. Cell body showing normal morphology. (B) Pmec-7YFP. Anterior cell process showing normal morphology from the same PLM cell as in A. (C) Pmec-7YFP/Pmec-3htt57Q19∷CFP. Cell body showing normal morphology and presence of perinuclear accumulation (blue arrows). (D) Pmec-7YFP/Pmec-3htt57Q19∷CFP. Anterior cell process showing normal morphology from the same PLM cell as in C. (E) Pmec-7YFP/Pmec-3htt57Q128∷CFP. Cell body showing CFP fusion accumulation adjacent to the nucleus (blue arrows) and at beginning of the process leading to the tail. (F) Pmec-7YFP/Pmec-3htt57Q128∷CFP. Anterior cell process from the same cell as in E showing morphological abnormalities (swelling: white arrows), sometimes in conjunction with the accumulation of CFP fusions.

We observed differences in aggregate formation in the PLM cell processes. Pmec-7 YFP animals displayed no aggregate formation, whereas Pmec-7YFP/Pmec-3htt57Q19∷CFP and Pmec-7YFP/Pmec-3htt57Q128∷CFP animals showed a significant difference in aggregate formation (Table 2). The aggregates had no consistent location and were of variable size and number.

Table 2.

Analysis of PLM process integrity

| Constructs (no. of lines) | Aggregates present, % | Abnormal morphology, % | Posterior Mec, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pmec–7YFP (5) | 0 | 13 ± 5 | 22 ± 9 |

| Pmec–7YFP/Pmec–3htt57Q19∷CFP (5) | 31 ± 9 | 13 ± 6 | 41 ± 14 |

| Pmec–7YFP/Pmec–3htt57Q128∷CFP (5) | 55 ± 10* | 49 ± 9†‡ | 85 ± 13† |

Aggregates, morphological abnormalities, and mechanosensory defects were each scored in separate animal populations (≥100 animals or 200 PLMs). Examples of aggregates and abnormal morphology are shown in Fig. 4. Results are means ± SD (n = 5).

Significantly different from Q19 (P < 0.001).

Significantly different from YFP alone and Q19 (P < 0.001). ANOVA tests were used.

100% of PLM cells scored with abnormal morphology showed abnormal morphology primarily occurring in axons.

The addition of the Pmec-7YFP marker allowed for inspection of the morphological integrity of PLM neuronal processes (Table 2). Various abnormalities were observed, the most prevalent was swelling of axonal processes. For example, swelling occurred on average in 49% of animals expressing CFP fusion proteins with 128 Glns (Fig. 4F). Although aggregates were observed on processes leading to and from the cell body, it is noticeable that swelling primarily occurred along the axonal processes (Fig. 4F) and did not fully correlate with the presence of a CFP fusion aggregate. Animals were also scored for a posterior Mec phenotype (Table 2). A significant difference was observed between 19 and 128 Glns for CFP fusions, as observed with GFP fusions (Table 1). Overall these data suggest that presence of aggregates in processes and morphological abnormalities in neuronal axons are two parameters that both show partial correlation with the Mec phenotype, suggesting other causes.

Cell Death Is Not Observed in Transgenic Animals.

To test for PLM apoptotic cell death, we used visual inspection under Nomarski microscopy, and visual inspection under fluorescence microscopy and absence of AO staining in the nucleus (37, 38). Although positive AO staining and GFP fluorescence both are detected under the same FITC filter, the GFP signal was weak or absent from the nucleus of PLM neurons in transgenic animals, allowing us to distinguish whether AO is reacting with nuclear DNA and whether cell death has occurred (data not shown). In contrast to previous reports on the cellular toxicity of expanded polyQ in C. elegans and Drosophila transgenic animals, we found no evidence of cell death in any young (3–4 days) or old (7–8 days) adults. PLM cells appeared normal, without apoptotic features (membrane blebbing, shrinkage) (37).

Discussion

In C. elegans, expanded polyQ produced mild nose touch abnormalities and low penetrance dye-filling defects, and produced cell death when expressed in sensitized ASH sensory neurons under control of the osm-10 promoter (40). A separate nonneuronal nematode model describes developmental delays when polyQ is expressed in the body wall muscles under control of the myo-2 promoter (41). In transgenic Drosophila, cell death produced by expanded polyQ expression in the eye has been used to identify genetic modifiers (42–45). Additionally, neurons appear to show selective susceptibility to polyQ-mediated degeneration (43).

Our C. elegans model complements other simple organism models and may reflect a different aspect of polyQ-mediated neuronal toxicity. Indeed, our results define in C. elegans significant neuronal dysfunction without cell death as a component of polyQ toxicity. Although the nature of the transgene used (length of expanded polyQ, nature of reporter sequence) may differ from one study to another, our observations suggest that polyQ-induced toxicity in C. elegans is neuronal cell-type dependent (40); our observations are consistent with a previously reported observation that mechanosensory neurons of the Drosophila eye are resistant to polyQ-induced toxicity, whereas photoreceptor neurons are highly sensitive (43). The difference in penetrance between anterior and posterior touch responsiveness may also reflect neuronal susceptibility to polyQ toxicity. PLM cell susceptibility to polyQ toxicity was detected for high expression levels. It is noticeable that cell death was, however, not induced, suggesting physiological relevance to polyQ toxicity. The availability of highly penetrant neuronal dysfunction in C. elegans provide a suitable system to study what is thought to be an early stage of polyQ neuronal toxicity in the pathogenesis of HD.

Our data define in vivo a relationship between neuronal dysfunction, aggregation, and neuropil abnormalities. GFP or CFP fusions containing 19, 88, or 128 Glns produced significant perinuclear aggregation without significant intranuclear aggregates. A similar pattern of cell body expression was reported in nematodes expressing the first 171 amino acids of htt with 150 Glns coexpressed with GFP in ASH sensory neurons, suggesting that perinuclear accumulation of polyQ-expanded htt in C. elegans neurons is not an artifact resulting from the presence of a GFP fusion or the length of N-terminal htt. GFP or CFP fusions containing 128 Glns in PLM neurons also produced significant aggregate formation and swelling of PLM cell processes in the absence of nuclear inclusions, suggesting the occurrence of a similar relationship in HD pathogenesis. Studies of mice models expressing truncated (20, 21), full-length htt (19), or polyQ alone (23) have suggested that neuropil aggregation might be associated with neuronal dysfunction. However, in these models the relative contribution of neuropil aggregates and NIIs was unclear. Our model showing aggregates along neuronal processes without NIIs indicate that NIIs are not required for neuronal dysfunction to occur. By using Pmec-7 YFP, we were able to assess the morphological integrity of PLM neurons expressing various polyQ constructs. Our findings indicate that PLM neurons expressing 128 Glns are more likely to display morphological abnormalities. Although the abnormalities showed a partial correlation to the mechanosensory defective phenotype associated with the expression of 128 Glns, they were detected mostly in PLM axons. Our hypothesis is that PLM cells expressing 128 Glns are unable to send a proper signal to the downstream interneurons (AVA, AVD, and PVC) because of a greatly impaired axon (32, 46). Another possibility is that PLM cells expressing 128 Glns are unable to receive input from touch. However, significant amounts of swelling of the posterior processes receiving touch were not noted. Aggregates and morphological abnormalities along neuronal processes partially correlated with the posterior Mec phenotype, suggesting they may not be wholly responsible for touch insensitivity.

It is thought that the touch receptor neurons of C. elegans are glutamatergic (47). Possibly then, glutamate-mediated neurotransmission is affected in animals expressing 128 Glns, thus producing the Mec phenotype. This may account for the partial correlation between aggregate formation and structural defects with touch insensitivity. Additionally, this would be consistent with the notion that N-terminal mutant htt species may interfere with glutamatergic neurotransmission through inappropriate binding to synaptic vesicles and altering glutamate uptake (22, 30, 48, 49).

Our observations (no cell death, no diffuse expression of a soluble fusion protein) are also consistent with the hypothesis that nuclear localization of soluble htt may be required for the occurrence of cell death as suggested by in vitro studies (14, 50).

In summary, the animals we introduce indicate that significant dysfunction without cell death of polyQ-expressing neurons may occur independently of nuclear aggregation and may directly involve axonal insults. These animals also indicate that neuronal dysfunction, a potentially important component of HD pathogenesis, may involve factors essential for neuronal process function. Our data also provide a suitable in vivo model system to screen for genetic and pharmacological suppressors of polyQ-mediated neuronal dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to M. Chalfie for laboratory accomodation when initiating these studies and for constructive discussions. We also thank A. Fire for C. elegans expression vectors, C. Ross for IT-15 constructs encoding 19 and 88 Glns, M. Schmid (Institut Universitaire d'Hématologie, Paris) for assistance with confocal microscopy, and the team of C. Bellané (Centre d'Etudes du Polymorphisme Humain) for DNA sequencing. This work was supported by the Hereditary Disease Foundation Cure HD Initiative (San Francisco). J.A.P. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Hereditary Disease Foundation Cure HD Initiative.

Abbreviations

- CFP

cyan fluorescent protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HD

Huntington's disease

- htt

huntingtin

- NII

neuronal intranuclear inclusions

- polyQ

polyglutamine

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

- AO

acridine orange

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

References

- 1.Harper P S. Hum Genet. 1992;89:365–376. doi: 10.1007/BF00194305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group. Cell. 1993;72:971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kowall N, Ferrante R, Beal M, Richardson E J, Sofroniew M, Cuello A, Martin J. Neuroscience. 1987;20:817–828. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase K, Schwarz C, Meloni A, Young C, Martin E, Vonsattel J P, Carraway R, Reeves S A, et al. Neuron. 1995;14:1075–1081. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Persichetti F, Ambrose C M, Ge P, McNeil S M, Srinidhi J, Anderson M A, Jenkins B, Barnes G T, Duyao M P, Kanaley L, et al. Mol Med. 1995;1:374–383. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeitlin S, Liu J P, Chapman D L, Papaioannou V E, Efstratiadis A. Nat Genet. 1995;11:155–163. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White J K, Auerbach W, Duyao M P, Vonsattel J P, Gusella J F, Joyner A L, MacDonald M E. Nat Genet. 1997;17:404–410. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dragatsis I, Levine M S, Zeitlin S. Nat Genet. 2000;26:300–306. doi: 10.1038/81593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zoghbi H Y, Orr H T. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:217–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C C, Faber P W, Persichetti F, Mittal V, Vonsattel J P, MacDonald M E, Gusella J F. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1998;24:217–233. doi: 10.1023/b:scam.0000007124.19463.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wellington C L, Singaraja R, Ellerby L, Savill J, Roy S, Leavitt B, Cattaneo E, Hackam A, Sharp A, Thornberry N, et al. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19831–19838. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turmaine M, Raza A, Mahal A, Mangiarini L, Bates G P, Davies S W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8093–8097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110078997. . (First Published June 27, 2000; 10.1073/pnas.110078997) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies S W, Turmaine M, Cozens B A, Raza A S, Mahal A, Mangiarini L, Bates G P. Philos Trans R Soc London B. 1999;354:971–979. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saudou F, Finkbeiner S, Devys D, Greenberg M E. Cell. 1998;95:55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81782-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuemmerle S, Gutekunst C A, Klein A M, Li X J, Li S H, Beal M F, Hersch S M, Ferrante R J. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:842–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutekunst C A, Li S H, Yi H, Mulroy J S, Kuemmerle S, Jones R, Rye D, Ferrante R J, Hersch S M, Li X J. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2522–2534. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02522.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy P H, Williams M, Charles V, Garrett L, Pike-Buchanan L, Whetsell W O, Jr, Miller G, Tagle D A. Nat Genet. 1998;20:198–202. doi: 10.1038/2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy P H, Charles V, Williams M, Miller G, Whetsell W O, Jr, Tagle D A. Philos Trans R Soc London B. 1999;354:1035–1045. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodgson J G, Agopyan N, Gutekunst C A, Leavitt B R, LePiane F, Singaraja R, Smith D J, Bissada N, McCutcheon K, Nasir J, et al. Neuron. 1999;23:181–192. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80764-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Li S H, Cheng A L, Mangiarini L, Bates G P, Li X J. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1227–1236. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schilling G, Becher M W, Sharp A H, Jinnah H A, Duan K, Kotzuk J A, Slunt H H, Ratovitski T, Cooper J K, Jenkins N A, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:397–407. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H, Li S H, Johnston H, Shelbourne P F, Li X J. Nat Genet. 2000;25:385–389. doi: 10.1038/78054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adachi H, Kume A, Li M, Nakagomi Y, Niwa H, Do J, Sang C, Kobayashi Y, Doyu M, Sobue G. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1039–1048. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.10.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sapp E, Penney J, Young A, Aronin N, Vonsattel J P, DiFiglia M. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:165–173. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199902000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sisodia S S. Cell. 1998;95:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81743-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nucifora F J, Sasaki M, Peters M, Huang H, Cooper J, Yamada M, Takahashi H, Tsuji S, Troncoso J, Dawson V, Dawson T, Ross C. Science. 2001;291:2423–2428. doi: 10.1126/science.1056784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holbert S, Denghien I, Kiechle T, Rosenblatt A, Wellington C, Hayden M R, Margolis R L, Ross C A, Dausset J, Ferrante R J, Neri C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1811–1816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041566798. . (First Published January 30, 2001; 10.1073/pnas.041566798) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuccato C, Ciammola A, Rigamonti D, Leavitt B R, Goffredo D, Conti L, MacDonald M E, Friedlander R M, Silani V, Hayden M R, et al. Science. 2001;293:493–498. doi: 10.1126/science.1059581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagai Y, Onodera O, Strittmatter W J, Burke J R. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;893:192–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun Y, Savanenin A, Reddy P H, Liu Y F. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24713–24718. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103501200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X J, Sharp A H, Li S H, Dawson T M, Snyder S H, Ross C A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4839–4844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Way J, Chalfie M. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1823–1833. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12a.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brenner S. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mello C, Fire A. Methods Cell Biol. 1995;48:451–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hobert O, Moerman D, Clark K, Beckerle M, Ruvkun G. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:45–57. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hengartner M. Dev Genet. 1997;21:245–248. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1997)21:4<245::AID-DVG1>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gumienny T, Lambie E, Hartwieg E, Horvitz H, Hengartner M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:1011–1022. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.5.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savage C, Xue Y, Mitani S, Hall D, Zakhary R, Chalfie M. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:2165–2175. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.8.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faber P W, Alter J R, MacDonald M E, Hart A C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:179–184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Satyal S H, Schmidt E, Kitagawa K, Sondheimer N, Lindquist S, Kramer J M, Morimoto R I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5750–5755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100107297. . (First Published May 16, 2000; 10.1073/pnas.100107297) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warrick J M, Chan H Y, Gray-Board G L, Chai Y, Paulson H L, Bonini N M. Nat Genet. 1999;23:425–428. doi: 10.1038/70532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marsh J L, Walker H, Theisen H, Zhu Y Z, Fielder T, Purcell J, Thompson L M. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:13–25. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kazemi-Esfarjani P, Benzer S. Science. 2000;287:1837–1840. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan H, Warrick J, Gray-Board G, Paulson H, Bonini N. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2811–2820. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.19.2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chalfie M, Sulston J E, White J G, Southgate E, Thomson J N, Brenner S. J Neurosci. 1985;5:956–964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-04-00956.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee R Y, Sawin E R, Chalfie M, Horvitz H R, Avery L. J Neurosci. 1999;19:159–167. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00159.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cha J H, Frey A S, Alsdorf S A, Kerner J A, Kosinski C M, Mangiarini L, Penney J B, Jr, Davies S W, Bates G P, Young A B. Philos Trans R Soc London B. 1999;354:981–989. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeron M M, Chen N, Moshaver A, Lee A T, Wellington C L, Hayden M R, Raymond L A. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;17:41–53. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters M F, Nucifora F C, Jr, Kushi J, Seaman H C, Cooper J K, Herring W J, Dawson V L, Dawson T M, Ross C A. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;14:121–128. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]