Abstract

The FeMo-cofactor of nitrogenase, a metal–sulfur cluster that contains eight transition metals, promotes the conversion of dinitrogen into ammonia when stored in the protein. Although various metal–sulfur clusters have been synthesized over the past decades, their use in the activation of N2 has remained challenging, and even the FeMo-cofactor extracted from nitrogenase is not able to reduce N2. Herein, we report the activation of N2 by a metal–sulfur cluster that contains molybdenum and titanium. An N2 moiety bridging two [Mo3S4Ti] cubes is converted into NH3 and N2H4 upon treatment with Brønsted acids in the presence of a reducing agent.

Nitrogenase—whose cofactor consists of a metal–sulfur cluster—catalyzes the production of NH3 from N2, but designing metal–sulfur complexes capable of promoting this conversion remains challenging. Here, the authors report on the activation of N2 by a metal–sulfur cluster containing [Mo3S4Ti] cubes, demonstrating NH3 and N2H4 production.

Introduction

Metal–sulfur clusters are a ubiquitous class of inorganic compounds, and span a wide range of structural and electronic features1,2. One unique function of protein-supported clusters is the conversion of N2 into NH3, which is mediated by the FeMo-cofactor of nitrogenase (Fig. 1a)3–5. The FeMo-cofactor can be extracted from the protein into organic solvents without significant degradation of its metal–sulfur core6,7. The extracted form catalyzes the reduction of non-native C1 substrates, such as CO and CO2 in the presence of reducing agents and protons to furnish CH4 and short-chain hydrocarbons8,9, and similar catalytic reductions can also be accomplished with the synthetic analog [Cp*MoFe5S9(SH)]3– (Cp* = η5-C5Me5)10. However, N2 cannot be reduced with the extracted FeMo-cofactor7 or its synthetic analogs, highlighting the difference in N2-reducing activity between the protein-supported FeMo-cofactor and discrete metal–sulfur clusters in solution. Thus, a molecular basis for the reduction of N2 on metal–sulfur clusters remains elusive, while some aqueous suspensions or emulsions of Fe–S or Mo–Fe–S compounds have been found to generate NH311–14 and some thiolate-supported Fe complexes have been found to activate N215–17. The cuboidal cluster Cp*3Ir3S4Ru(tmeda)(N2) (tmeda = tetramethylethylenediamine) is the only structurally characterized example for the binding of N2 to a metal–sulfur cluster, although the conversion of the Ru-bound N2 has not yet been achieved18.

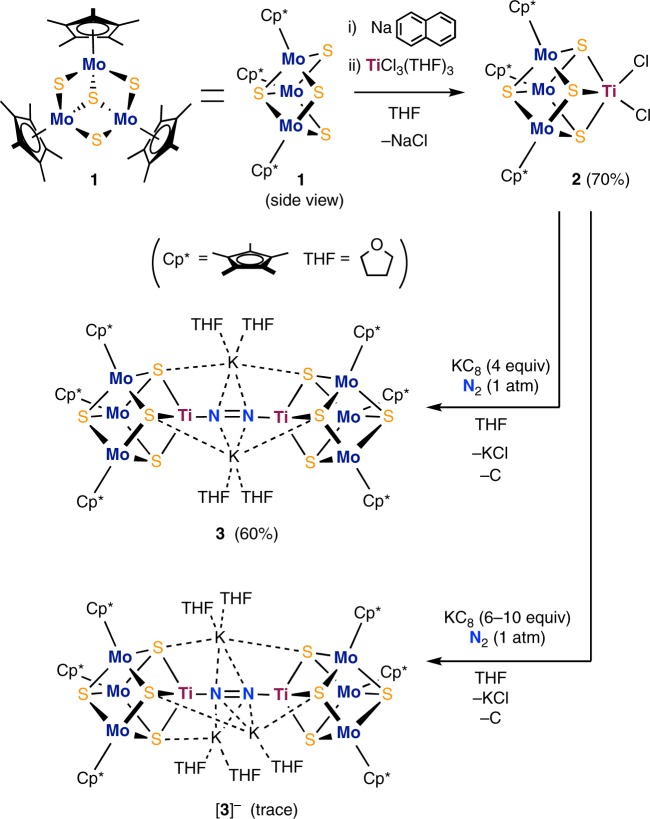

Fig. 1.

Structure of the nitrogenase FeMo-cofactor. a The resting-state structure. The peptide chains of cysteine (Cys) and histidine (His), as well as a part of (R)-homocitrate are omitted for clarity. Color legend: C, gray; Fe, black; Mo, dark blue; S, yellow; O, red; N, light blue. b Wire-frame drawing of the inorganic part of the FeMo-cofactor, which highlights the fused form of the two cubes

It should be noted that the structure of the FeMo-cofactor can be seen as a fused form of two cubes (Fig. 1b), implying the utility of cubes in the activation of N2. However, synthetic examples are limited for the fused form of such metal–sulfur cubes19–23, and a carbon-centered derivative still remains unprecedented. In order to develop a strategy for the activation of N2 on synthetic metal–sulfur clusters, we examined independent cubes in this study. Our design (Fig. 2) is based on the trinuclear Mo–sulfur cluster platform Cp*3Mo3(μ-S)3(μ3-S) (1)24 for the accommodation of a metal atom via three doubly bridging sulfur atoms to furnish a cubic structure. Ti was chosen as the additional metal to demonstrate the proof-of-concept, on the basis of successful examples of Ti complexes in N2 chemistry25, e.g. some recent studies on the activation of N2 mediated by Ti–hydride complexes26,27. The resulting [Mo3S4Ti] cluster (Fig. 2, top right) is reduced in the presence of N2, to generate a Ti-based reaction site for the activation of N2. Herein, we report the activation of N2, as well as its conversion into NH3 and N2H4, on a Mo–Ti–S cluster.

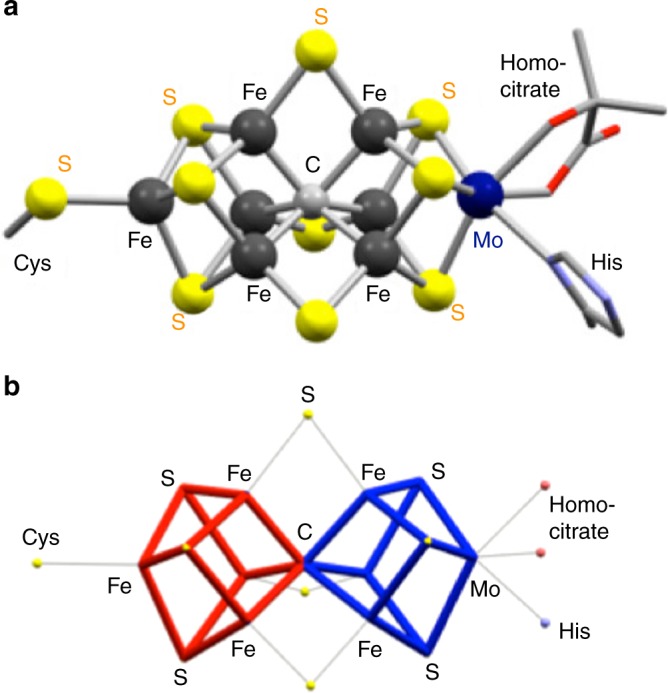

Fig. 2.

Reactions in this study. Synthesis of the cubic [Mo3S4Ti] cluster 2, the N2-binding cluster 3, and its 1e reduced form [3]–; Cp* = η5-pentamethylcyclopentadienyl; THF tetrahydrofuran

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of a cubic [Mo3S4Ti] cluster and an N2-cluster

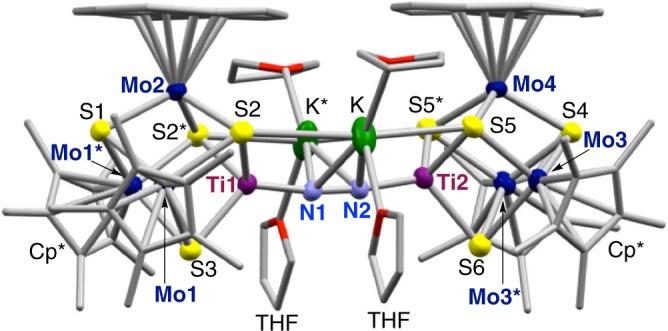

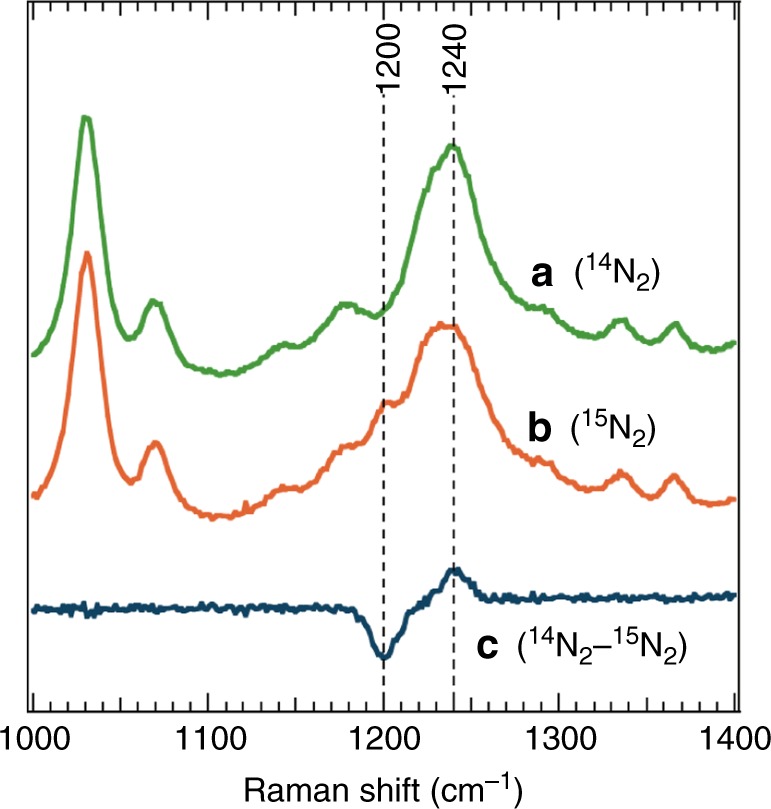

The cubic [Mo3S4Ti] precursor cluster Cp*3Mo3S4TiCl2 (2) was synthesized in 70% yield in tetrahydrofuran (THF) from the reaction of in situ generated [1]– with TiCl3(THF)3 (Fig. 2), in a manner similar to the synthesis of cubic clusters from trinuclear Mo–sulfur clusters28,29. The molecular structure of 2 (Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 3) reveals a nearly square-pyramidal geometry of titanium with an apical sulfur atom, where the Ti–Sapical distance (2.2799(7) Å) is shorter than the Ti–Sbasal distances (2.3888(6) and 2.4272(6) Å). The Ti–Cl distances (2.3429(7) and 2.3812(7) Å) are close to those in a Ti(III) complex (average 2.353(4) Å) supported by three chlorides and a tridentate phosphine ligand30. The reduction of 2 with potassium graphite (KC8) in THF under an atmosphere of N2 resulted in the coordination and reduction of N2 to form the brown cluster [K(THF)2]2[Cp*3Mo3S4Ti]2(μ-N2) (3) in 60% yield, in which an N2 moiety bridges two [Mo3S4Ti] cubes via binding to the Ti atoms. Product(s) of analogous reactions under atmospheres of H2 or Ar have not been characterized so far. Cluster 3 is diamagnetic, and the 15N NMR spectrum of 15N-labeled 3 exhibited a signal at –75.4 ppm relative to CH3NO2 in THF-d8 (Supplementary Figure 5). A single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of 3 established that N2 is linearly aligned with the two Ti atoms to form a Ti–N=N–Ti moiety (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figure 4). Its N–N distance (1.294(7) Å) is comparable to the longest bonds reported for Ti–N=N–Ti complexes31–33, suggesting a high degree of N2 reduction. The N–N distance in 3 is slightly longer than that in H3CN=NCH3 (1.25 Å)34, but shorter than that in H2N–NH2 (1.46 Å)25, indicating a character between N=N double and N–N single bonds for the bridging N2 in 3. This notion was supported by resonance-Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figure 8), which showed a νNN band of 3 at 1240 cm−1 based on the difference spectrum of 3 and 15N-labeled 3. This νNN frequency falls between those of H3CN=NCH3 (1575 cm−1)35 and H2N–NH2 (1111 cm−1)36. The observed shift (40 cm−1) between 3 (1240 cm−1) and 15N-labeled 3 (1200 cm−1) is consistent with the calculated shift (42 cm−1) for the replacement of 14N2 by 15N2 assuming a diatomic harmonic oscillator.

Fig. 3.

Molecular structure of the N2 cluster 3. For clarity, carbon and oxygen atoms are drawn as capped sticks, while other atoms are drawn with thermal ellipsoids set at 50% probability. Color legend: C, gray; Mo, dark blue; Ti, purple; S, yellow; O, red; N, light blue; K, green. Selected bond distances (Å): N1–N2 1.294(7), Mo1–Mo1* 2.6766(8), Mo1–Mo2 2.8853(6), Mo3–Mo3* 2.7392(8), Mo3–Mo4 2.8518(6), Mo1–Ti1 3.0315(10), Mo2–Ti1 3.0908(12), Mo3–Ti2 3.0301(10), Mo4–Ti2 3.0778(12), Ti1–N1 1.802(5), Ti2–N2 1.798(5), K–N1 2.797(3), K–N2 2.782(3)

Fig. 4.

Spectroscopic characterization of the Ti-N=N-Ti moiety. Resonance-Raman spectra for 3 (a, green line) and 15N-labeled 3 (b, orange line), as well as their difference spectrum (c, dark blue line) in THF at –30 °C

Owing to the robust Cp*–Mo and Mo–S bonds in the present system, we speculate that the three Mo atoms remain intact during the activation of N2, leaving Ti as the reaction site in each cube. These robust bonds would also help to avoid the degradation of the cubic structure by aggregation or fragmentation.

Conversion of the N2 moiety into NH3 and N2H4

The high degree of reduction in 3 prompted us to attempt a stoichiometric conversion of the coordinated N2 into NH3 and N2H4. Upon treatment of 3 with protons from either H2O or HCl, the color changed from brown to green, and NH3, N2H4, and [1]+ were detected. The resulting products NH3 and N2H4 were quantified by indophenol and azo-dye titration methods, respectively (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2)37,38. As summarized in Table 1 (entries 1 and 4), small to moderate amounts of NH3 (0.12(3)–0.29(5) equiv) and N2H4 (0.12(10)–0.60(3) equiv) were detected by protonation of 3 with an excess H2O or HCl. While the length of the N–N bond in 3 indicates that a reduction has occurred, additional electrons are required for the cleavage of the N–N bond to form NH3. Therefore 3 was treated with KC8 and H2O or HCl. In the presence of 6 equiv of KC8, the average amount of NH3 generated by protonation with H2O increased from 0.12(3) to 0.47(27) equiv (entry 5), while the fluctuations observed allow only a cautious comparison. The NH3 yields in entries 4 and 5 (HCl) are comparable and within error. The yields of N2H4 in entries 2 (0.56(10) equiv from H2O) and 5 (0.19(6) equiv from HCl) remained comparable to those of reactions in the absence of KC8. The formation of N2H4 from the Ti–N=N–Ti moiety is reasonable, as this N–N bond exhibits an N=N double and N–N single bond character. In the presence of 0–6 equiv of KC8, subsequent protonation by H2O provided approximately three times the amount of N2H4 than the reactions with HCl. Such acid-dependent selectivity may arise from the affinities of the conjugate bases (OH– or Cl–) toward metals, where the high oxophilicity of the Ti and K atoms can facilitate the coordination of H2O onto these atoms, which could lead to an efficient protonation of the neighboring Ti–N=N–Ti moiety.

Table 1.

Protonation of 3 in the presence/absence of KC8a

| Entry | Proton source | KC8 (equiv) | NH3 (equiv) | N2H4 (equiv) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H2O | 0 | 0.12(3) | 0.60(3) |

| 2 | H2O | 6 | 0.47(27) | 0.56(10) |

| 3 | H2O | 100 | 1.20(19) | n.d.b |

| 4 | HCl | 0 | 0.29(5) | 0.12(10) |

| 5 | HCl | 6 | 0.43(15) | 0.19(6) |

| 6 | HCl | 100 | 0.20(8) | n.d.b |

a Yields represent the average of three runs. Standard deviations are given in parentheses

b n.d. = not detected

Even in the presence of a slight excess (6 equiv) of KC8, conversion of the N2 moiety of 3 into NH3 was not complete and notable amounts of N2H4 were detected (entries 2 and 5). These results indicate that some of the added KC8 remains unreacted with the N2 cluster and is subsequently quenched directly by H2O or HCl. However, the formation of N2H4 was suppressed when a large excess of KC8 was added prior to protonation (entries 3 and 6). While the protonation with HCl did not increase the amount of NH3 (entry 6), the maximum yield of NH3 (1.20(19) equiv) was achieved when 100 equiv KC8 were added prior to the protonation with H2O (entry 3). When conditions identical to those of entry 3 were applied for the 15N-enriched 3 under an atmosphere of 14N2, the 1H NMR spectrum of the resulting ammonium salt indicated the exclusive formation of 15NH3, which originates from the Ti–15N=15N–Ti moiety (Supplementary Figure 15). After addition of an excess of protons to 3, the Ti atom probably dissociates from the [Mo3S4Ti] cube, which is supported by the appearance of an intense signal of [1]+ in the electro-spray ionization mass (ESI-MS) spectrum of the resulting mixture (Supplementary Figure 16) and the color change of the mixture from dark brown to green. Thus, at this stage, the possibility of N2 functionalization after dissociation of the Ti atom cannot be ruled out unequivocally.

It has been reported that metal–sulfur clusters exhibit stability across various oxidation states, which allows the storage and transportation of electrons39,40. It is therefore worthy of notice that the 1e-reduced cluster [3]– was obtained in trace amounts from the reaction of 2 with 6–10 equiv of KC8 under an atmosphere of N2 (Fig. 2, bottom). The characterization of [3]– was carried out only by 1H NMR and crystallographic analysis due to the trace amounts available. Cluster [3]– is paramagnetic and its 1H NMR spectrum in THF-d8 exhibited a broad Cp* signal at 5.84 ppm (Supplementary Figure 10). The molecular structure of [3]– (Supplementary Figure 9) revealed an interaction of three potassium ions with the bridging N2 moiety, where the N–N distance (1.293(5) Å) is comparable to that in 3 (1.294(7) Å). A structural comparison between the [Mo3S4Ti] cubes of 3 and [3]– reveals the elongation of distances in [3]–. In detail, a relatively large contribution of the metal atoms for the storage of the additional electron is indicated by the larger differences in the average distances of Mo–Ti (3.0487(12) Å for 3 and 3.0242(8) Å for [3]–) and Mo–Mo (2.8150(8) Å for 3 and 2.8668(6) Å for [3]–), rather than the average metal–sulfur distances, i.e. Mo–S (2.3952(16) Å for 3 and 2.3966(11) Å for [3]–), and Ti–S (2.328(2) Å for 3 and 2.3297(13) Å for [3]–). The detailed reaction pathways for the formation of NH3 and N2H4 from 3 or [3]– remain unclear at this point, as the dissociation of the Ti atom from the [Mo3S4Ti] cube renders the identification of possible cluster intermediates difficult.

In summary, we successfully achieved the activation of N2 and its conversion into sub-stoichiometric mixtures of NH3 and N2H4 on synthetic Mo–Ti–S cubes by selectively generating the Ti-based reaction sites. This work thus represents a step towards the assembly of structural and functional models for the FeMo-cofactor.

Methods

General procedure

All reactions and manipulations were carried out under an atmosphere of nitrogen using standard Schlenk line or glove box techniques. Solvents for reactions were purified by passing over columns of activated alumina and a supported copper catalyst. TiCl3(THF)341, [Cp*3Mo3S4][PF6] ([1]+)42, and KC843 were prepared according to literature procedures. All other reagents were purchased from common commercial sources and used without further purification. General considerations on the measurements and experiments as well as some experimental details are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Modified synthesis of Cp*3Mo3S4 (1)

Compound 1 was originally synthesized from the reaction of Cp*Mo(StBu)3 (tBu = tert-butyl) with Na/Hg24, but this reaction is not ideally suitable for a gram-scale synthesis. Instead, cluster 1 was synthesized on a multi-gram scale through the reduction of [1]+. For that purpose, KC8 (1.36 g, 10.06 mmol) was added in portions to a THF (150 mL) suspension of [1]+ (9.78 g, 10.12 mmol) at room temperature. After stirring this mixture overnight, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The residue was extracted four times with toluene (350 mL). The extract was stored at –30 °C to precipitate green blocks of 1. The mother liquor was concentrated to ca. 1/5 of the original volume and stored at –30 °C to obtain a second crop. The total amount of green crystals of 1 was 6.17 g (7.51 mmol, 83%). This product was characterized by comparison with 1H NMR data in the literature24. 1H NMR (C6D6): δ 8.56 (w1/2 = 14 Hz, Cp*).

Synthesis of Cp*3Mo3S4TiCl2 (2)

A THF (20 mL) solution of 1 (1.00 g, 1.22 mmol) was cooled to –100 °C, and a THF solution of sodium naphthalenide (19.5 mM, 62 mL, 1.21 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was gradually warmed to room temperature to give a dark green solution. The mixture was again cooled to –100 °C, and TiCl3(THF)3 (451 mg, 1.22 mmol) was added. The reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 5 days, affording a dark brown suspension. After concentration to ca. 5 mL under reduced pressure, the mixture was cooled to –30 °C, which caused the precipitation of a dark brown powder. The supernatant was removed and the dark brown powder was washed with hexane (20 mL × 2). The brown powder was dissolved into CH2Cl2 (15 + 3 mL), and hexane (100 mL) was layered on top of this solution. The subsequent slow diffusion led to the formation of brown plates of Cp*3Mo3S4TiCl2·CH2Cl2 (2·CH2Cl2). These brown crystals were washed with hexane (15 mL × 2), and then dissolved in THF (15 mL). After stirring overnight, THF and CH2Cl2 were removed under reduced pressure to give a brown powder of 2 (801 mg, 0.854 mmol, 70%). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 9.23 (w1/2 = 8 Hz, Cp*); solution magnetic moment (CD2Cl2, 297 K): μeff = 1.3 μB; Cyclic voltammogram (2 mM in CH2Cl2, potential vs. (C5H5)2Fe/[(C5H5)2Fe]+): E1/2 = –0.28, –1.34 V; UV/Vis (CH2Cl2): λmax 415 nm (sh, 1200 cm−1 M−1), 753 nm (660 cm−1 M−1); analysis (calcd., found for C30H45Cl2Mo3S4Ti): C (38.31, 38.77), H (4.82, 4.70), S (13.64, 13.24).

Synthesis of [K(THF)2]2[Cp*3Mo3S4Ti]2(μ-N2) (3)

Cluster 2 (200 mg, 0.213 mmol) and KC8 (116 mg, 0.858 mmol) were charged into one side of an H-shaped glass vessel (Supplementary Fig. 3). The other arm of the vessel was charged with THF (10 mL), which was vacuum-transferred to the solid mixture at 78 K. The vessel was filled with N2 (1 atm) and then sealed. The mixture was slowly warmed using a methanol/liquid N2 slurry. Stirring of the mixture with a magnetic stirring bar was initiated, once part of frozen THF had melted. The mixture was gradually warmed to room temperature, giving a dark red-brown suspension. Stirring was continued overnight, before the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was extracted with THF (50 mL). The solution was filtered, concentrated to ca. 3 mL, and stored at –30 °C. Cluster 3 (136 mg, 0.064 mmol, 60%) was obtained as dark-brown crystalline blocks, which were washed with pentane. 1H NMR (THF-d8): δ 1.70 (Cp*); 13C{1H} NMR (THF-d8): δ 13.6 (C5Me5), 96.3 (C5Me5); UV/Vis (THF): λmax 356 nm (35800 cm−1 M−1), 500 nm (15,800 cm−1 M−1); Resonance-Raman spectrum (0.07 mM in THF, λex 355 nm, –30 °C): 1240 cm-1 (νNN); analysis (calcd., found for C76H122K2Mo6N2O4S8Ti2): C (42.78, 42.36), H (5.76, 5.80), N (1.31, 1.37), S (12.02, 12.27).

Synthesis of 15N2-labeled 3

This cluster was synthesized in a manner similar to that of 3, using cluster 2 (173 mg, 0.184 mmol), KC8 (100 mg, 0.740 mmol), and 15N2 (1 atm). Crystals of 15N2-labeled 3 were obtained in 60% yield (117 mg, 0.055 mmol). 15N{1H} NMR (THF-d8, referenced to external CH3NO2): δ –75.4; Resonance-Raman spectrum (THF, –30 °C): 1200 cm−1 (νNN).

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1577330–1577332. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data are available from the authors upon request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the PRESTO program of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JPMJPR1342), a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (16H04116) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), the Hori Sciences and Arts Foundation, and the Takeda Science Foundation. The authors are grateful to Prof. K. Tatsumi for providing access to instruments, to Prof. H. Seino for generous advice on the quantification of NH3 and N2H4, to Prof. S. Muratsugu for generous advice on electrochemical measurements, to Profs. K. Awaga and M. M. Matsushita for aiding us in recording the ESR measurements, and to R. Hara for technical assistance.

Author contributions

Y. O. conceived and designed the experiments; K. U. performed the experiments; T. O. and T. O. carried out the resonance Raman spectroscopic analysis; R. E. C. performed crystallographic analysis; M. T. participated in the discussion; Y. O. prepared the manuscript with input from all authors.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Deceased: Takashi Ogura.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-05630-6.

References

- 1.Krebs B, Henkel G. Transition-metal thiolates: from molecular fragments of sulfide solids to models for active centers in biomolecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1991;30:769–788. doi: 10.1002/anie.199107691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holm RH, Lo W. Structural conversions of synthetic and protein-bound iron-sulfur clusters. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:13685–13713. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman BM, Lukoyanov D, Yang ZndashY, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Mechanism of nitrogen fixation by nitrogenase: the next stage. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:4041–4062. doi: 10.1021/cr400641x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spatzal T, et al. Evidence for interstitial carbon in nitrogenase FeMo cofactor. Science. 2011;334:940. doi: 10.1126/science.1214025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lancaster KM, et al. X-ray emission spectroscopy evidences a central carbon in the nitrogenase iron–molybdenum cofactor. Science. 2011;334:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1206445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah VK, Brill WJ. Isolation of an iron-molybdenum cofactor from nitrogenase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:3249–3253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith BE, et al. Exploring the reactivity of the isolated iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999;185–186:669–687. doi: 10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00017-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee CC, Hu Y, Ribbe MW. ATP-independent formation of hydrocarbons catalyzed by isolated nitrogenase cofactors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:1947–1949. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu Y, Ribbe MW. Nitrogenases—a tale of carbon atom(s) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:8216–8226. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanifuji K, et al. Structure and. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:15633–15636. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dörr M, et al. A possible prebiotic formation of ammonia from dinitrogen on iron sulfide surfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:1540–1543. doi: 10.1002/anie.200250371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka K, Hozumi Y, Tanaka T. Dinitrogen fixation catalyzed by the reduced species of [Fe4S4(SPh)4]2– and [Mo2Fe6S8(SPh)9]3–. Chem. Lett. 1982;11:1203–1206. doi: 10.1246/cl.1982.1203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banerjee A, et al. Photochemical nitrogen conversion to ammonia in ambient conditions with FeMoS-chalcogels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:2030–2034. doi: 10.1021/ja512491v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, et al. Nitrogenase-mimic iron-containing chalcogels for photochemical reduction of dinitrogen to ammonia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:5530–5535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605512113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Čorić I, et al. Binding of dinitrogen to an iron-sulfur carbon site. Nature. 2015;526:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature15246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takaoka A, Mankad NP, Peters JC. Dinitrogen complexes of sulfur-ligated iron. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8440–8443. doi: 10.1021/ja2020907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creutz SE, Peters JC. Diiron bridged-thiolate complexes that bind N2 at the FeIIFeII, FeIIFeI, and FeIFeI redox states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:7310–7313. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mori H, Seino H, Hidai M, Mizobe Y. Isolation of a cubane-type metal sulfido cluster with a molecular nitrogen ligand. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:5431–5434. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SC, Holm RH. The clusters of nitrogenase: synthetic methodology in the construction of weak-field clusters. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:1135–1157. doi: 10.1021/cr0206216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohki Y, Tatsumi K. New synthetic routes to metal-sulfur clusters relevant to the nitrogenase metallo-clusters. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2013;639:1340–1349. doi: 10.1002/zaac.201300081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Zuo JL, Zhou HC, Holm RH. Rearrangement of symmetrical dicubane clusters into topological analogues of the P cluster of nitrogenase: nature’s choice? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:14292–14293. doi: 10.1021/ja0279702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohki Y, Ikagawa Y, Tatsumi K. Synthesis of new [8Fe-7S] clusters: a topological link between the core structures of P-cluster, FeMo-co, and FeFe-co of nitrogenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10457–10465. doi: 10.1021/ja072256b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohki Y, et al. Synthesis, structures, and electronic properties of [8Fe-7S] cluster complexes modeling the nitrogenase P-cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13168–13178. doi: 10.1021/ja9055036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cramer RE, Yamada K, Kawaguchi H, Tatsumi K. Synthesis and structure of a Mo3S4 cluster complex with seven cluster electrons. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:1743–1746. doi: 10.1021/ic951103z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fryzuk MD, Johnson SA. The continuing story of dinitrogen activation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000;200-202:379–409. doi: 10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00264-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shima T, et al. Dinitrogen cleavage and hydrogenation by a trinuclear titanium polyhydride complex. Science. 2013;340:1549–1552. doi: 10.1126/science.1238663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B, et al. Dinitrogen activation by dihydrogen and a PNP-ligated titanium complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:1818–1821. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b13323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shibahara T. Syntheses of sulphur-bridged molybdenum and tungsten coordination compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1993;123:73–147. doi: 10.1016/0010-8545(93)85053-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hidai M, Kuwata S, Mizobe Y. Synthesis and reactivities of cubane-type sulfido clusters containing noble metals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:46–52. doi: 10.1021/ar990016y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker, R. J. et al. Early transition metal complexes of triphosphorus macrocycles. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1975–1984 (2002).

- 31.Duchateau R, Gambarotta S, Beydoun N, Bensimon C. Side-on versus end-on coordination of dinitrogen to titanium(II) and mixed-valence titanium(I)/titanium(II) amido complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:8986–8988. doi: 10.1021/ja00023a080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chomitz WA, Sutton AD, Krinsky JL, Arnold J. Synthesis and reactivity of titanium and zirconium complexes supported by a multidentate monoanionic [N2P2] ligand. Organometallics. 2009;28:3338–3349. doi: 10.1021/om8011932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakanishi Y, Ishida Y, Kawaguchi H. Nitrogen-carbon bond formation by reactions of a titanium-potassium dinitrogen complex with carbon dioxide, tert-butyl isocyanate, and phenylallene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:9193–9197. doi: 10.1002/anie.201704286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Almenningen A, Anfinsen IM, Haaland A. An electron diffraction study of azomethane, CH3NNCH3. Acta Chem. Scand. 1970;24:1230–1234. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.24-1230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pearce RAR, Levin IW, Harris WC. Raman spectra and vibrational potential function of polycrystalline azomethane and azomethane-d6. J. Chem. Phys. 1973;59:1209–1216. doi: 10.1063/1.1680170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gulaczyk I, Kreglewski M, Valentin A. The N-N stretching band of hydrazine. J. Mol. Spectr. 2003;220:132–136. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2852(03)00106-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaney AL, Marbach EP. Modified reagents for determination of urea and ammonia. Clin. Chem. 1962;8:130–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watt GW, Chrisp JD. A spectrophotometric method for the determination of hydrazine. Anal. Chem. 1952;24:2006–2008. doi: 10.1021/ac60072a044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu J, et al. Metalloproteins containing cytochrome, iron−sulfur, or copper redox centers. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:4366–4469. doi: 10.1021/cr400479b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohta S, Ohki Y. Impact of ligands and media on the structure and properties of biological and biomimetic iron-sulfur clusters. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017;338:207–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.02.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones NA, Liddle ST, Wilson C, Arnold PL. Titanium(III) alkoxy-N-heterocyclic carbenes and a safe, low-cost route to TiCl3(THF)3. Organometallics. 2007;26:755–757. doi: 10.1021/om060486d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takei I, et al. Synthesis of a new family of heterobimetallic tetranuclear sulfido clusters with Mo2Ni2Sx (x = 4 or 5) or Mo3M’S4 (M’ = Ru, Ni, Pd) cores. Organometallics. 2003;22:1790–1792. doi: 10.1021/om021033l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bergbreiter DE, Killough JM. Reactions of potassium-graphite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:2126–2134. doi: 10.1021/ja00475a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1577330–1577332. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data are available from the authors upon request.