Abstract

We aimed to assess the quality of life (QOL) of the patients with cervical cancer after initial treatment, the factors affecting QOL and their clinical relevance. A total of 256 patients with cervical cancer who visited Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University from January 2017 to December 2017 were enrolled in this study. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core-30 item (EORTC QLQ-C30) and cervical cancer module (EORTC QLQ-CX24) was used to assess the QOL of patients. More than half of the patients with cervical cancer reported an excellent QOL. Symptoms mostly experienced were insomnia, constipation, financial difficulties, and menopausal symptoms. Global QOL and social functioning were statistically associated with education level, occupation, the area of living, family income and treatment modality. Similarly, role functioning showed significant association with the stage of cancer, treatment modality and time since diagnosis. The rural area of living and poor economic status of the patients with cervical cancer has a negative impact on overall quality of life. Younger and educated patients are more worried about sexuality. Patients treated with multiple therapies had more problems with their QOL scales than patients treated with surgery only.

Introduction

Cervical Cancer (CC) is the fourth most common female cancer with estimated incidence and mortality of 528,000 and 266,000 respectively in the world1. China alone has around 18.7% (98,900 cases) of the total CC and 11.5% (30,500 deaths) of the total mortality in the world2. Although the overall incidence of CC in China is lower than African or South Asian countries, there are specific regions such as Hubei province, the central part of China, with one of the highest prevalence of CC3. Moreover, Wufeng county in Hubei province has the second highest incidence of CC and the highest mortality rate in China4.

Effective therapy for CC including surgery and concurrent chemoradiation can have a cure rate of 80% of women with early-stage disease [International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stages I–II] and 60% of women with stage III disease5. The survival rate of CC in China is also increasing probably due to the free screening program that began in 2009. However, the quality of life after treatment has been primarily neglected6. The majority of patients with CC are diagnosed at a relatively younger age, and most of them have a long additional life expectancy with sequelae of the disease and its treatment. Therefore, the quality of life in CC survivors has become a more significant issue with the increased numbers of survivors7.

The Quality of Life (QOL) of patients with CC is an essential assessment for personalizing treatment and providing better care. CC survivors had clinically significant problems with social functioning, constipation, diarrhea, severe lymphedema, menopausal symptoms, reduced body image, sexual or vaginal functioning, as well as difficulties with their finances compared with the general female population. Studies have identified that health-related QOL can also help to predict survival in patients with cancer8–10.

There is a dearth of studies focused on the holistic care of the patients with CC primarily on post-treatment long-term QOL in China. It is essential to conduct such studies to identify and address the problem to improve their QOL. The objective of this study was to assess the QOL of the patients with CC after the initial treatment and identify factors that affect the QOL to provide a basis for improved comprehensive clinical care.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted after approval by the institutional review board of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Department of Gynecological Oncology, Wuhan, Hubei, China. We obtained written informed consent from all the participants. All methods in this study were performed by the relevant guidelines and regulations. A total of 256 patients with CC who visited Zhongnan Hospital from January 2017 to December 2017 and who met the eligibility criteria enrolled in this study. Women with any stage of CC including recurrence (FIGO stage I, II, III and IV), able to understand Chinese and willing to participate in this study were included. Women who declined or who refused to cooperate and patients with psychiatric co-morbidity, communication disorders and or severe other medical condition were excluded from this study.

Treatment guideline for cervical cancer in Zhongnan Hospital is as follows: i) early stage cervical cancer (IA- IIA2) is treated by either surgery and or radiotherapy; ii) advanced stage cervical cancer (IIB – IVA) is treated by primary chemoradiation. However, selected patients with stage IIB are treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Metastatic disease (IVB) primarily treated with chemotherapy. Indications for surgery combined with adjuvant treatment are the presence of one or more pathologic risk factors. Those risk factors are >1/3 stromal invasion, LVSI, and tumor size (i.e., Sedlis criteria) as well as tumor histology of adenocarcinoma and close or positive surgical margins as per National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline11.

Measurements

The survey instrument consisted of four parts. The first section included demographic information of women, which was collected by interviewing the participant with a structured questionnaire. The second section consisted of clinical characteristics, and it was obtained by reviewing the medical records. The third section was the validated Chinese version of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core-30 item (EORTC QLQ-C30) and EORTC QLQ-CX24 (Cervical cancer module)12–14. The EORTC questionnaire has been widely employed and tested in different studies among the various cultural group and demonstrated acceptable validity13,15–21. The EORTC QLQ-CX24 was selected to assess the QOL of CC patients as it is the most appropriate and valid health-related quality of life cervical cancer specific tool for self-reported evaluation of health status among them22. The Chinese version of the EORTC QLQ-CX24 was validated among Chinese cervical cancer patients and reported as a reliable and efficient instrument in clinical research to study QOL13,21.

The EORTC QLQ-C30 incorporates five functioning domains (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain, and nausea and vomiting), global health and overall QOL scales and six single items that assess additional symptoms commonly reported by cancer patients (dyspnea, appetite loss, sleep disturbance, constipation, and diarrhea) along with perceived financial difficulties12. The EORTC QLQ-CX24 includes 24 items consisting of three multi-item scales (symptom experience, body image, and sexual/vaginal functioning scale) and six single-item scales15. In the present study, the reliability coefficient for EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-CX24 was 0.830 and 0.801 respectively.

All scores on the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CX24 were transformed into 0 to 100 scale according to the EORTC QLQ scoring manual23. Higher scores in GHS and functioning scale represent better levels of functioning and worse levels of symptoms in symptom scales. For EORTC QLQ-CX24, higher scores indicate more symptoms/problems. For the scales sexual activity and sexual enjoyment, a higher score means fewer problems or proper functioning24.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, SPSS (version 16.0) was used. Each scale of EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CX24 based on QOL scores were dichotomized into problematic and non-problematic. The problematic group was defined as one with a global QOL or a functioning score of 33 or less or with a symptom score of more than 6623,25.

Normality tests were carried out for the Global Health Status (GHS), the Functioning Scale, and the Symptom Scale. Data were analyzed with non-parametric tests namely Mann Whitney U test and Kruskal Wallis tests. The patients were divided into groups according to age (<45 years, >46 years), education (illiterate, literate), residence (rural, urban), stage (I, II, III, IV), and treatment modality (surgery only, surgery + radiotherapy + chemotherapy, radiotherapy and or chemotherapy). Multivariable linear regression was performed to explore associations between overall QOL (GHS) and patient and treatment-related variables. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Clinical relevance was tested to determine statistically significant results regarding (difference of >10 Points)26.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 256 patients with CC were enrolled in the study. The mean age of the patients was 53.4 ± 10.5 years. Almost 44% of the patients reported annual family income less than 1450 (USD). The proportion of patients in FIGO stage I, II, III, and IV were 40.2%, 46.5%, 7.8% and 5.5% respectively. Around 54% of patients had surgery combined with chemo-radiotherapy (Table S1).

QOL Score

More than half (58.6%) had good global health status, and the majority of the patients had proper functioning in QLQ-C30 functioning scale (range: 71.1% to 89.1%). Financial difficulty was perceived by 53.9% of the patients; insomnia (25.0%) and constipation (21.9%) were the most experienced symptoms. Among the sexually active patients (N = 72, 28.1%), 25% had a problem with sexual enjoyment functioning. Regarding symptoms experienced in QLQ-CX24 scale, 12.5% had menopausal symptoms (Table 1).

Table 1.

QLQ – C30 & CX24 unadjusted scale scores, the percentage of subjects with problems & in good conditiona. N = 256.

| Variables | Number of items | Mean (SD) | 95% C.I. | Scoring <33.3 (%) | Scoring >66.7 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QLQ -C30 Functional scales b | |||||

| Global health status/ QOL | 2 | 65.3 (23.0) | 62.2–68.0 | 4.7 | 58.6 |

| Physical functioning | 5 | 84.3 (16.8) | 82.0–86.4 | 0 | 86.7 |

| Role functioning | 2 | 84.4 (22.4) | 81.5–87.2 | 3.1 | 89.1 |

| Emotional functioning | 4 | 80.3 (18.2) | 77.8–82.4 | 0 | 84.4 |

| Cognitive functioning | 2 | 80.1 (19.3) | 77.7–83.4 | 0 | 84.0 |

| Social functioning | 2 | 70.8 (26.9) | 67.4–74.0 | 3.9 | 71.1 |

| QLQ-C30 Symptom scales c | |||||

| Fatigue | 3 | 24.8 (19.5) | 22.4–27.3 | 58.6 | 5.5 |

| Nausea & vomiting | 2 | 15.4 (22.5) | 12.7–18.4 | 72.7 | 4.7 |

| Pain | 2 | 17.7 (20.6) | 15.3–20.4 | 68.8 | 5.5 |

| Dyspnoea | 1 | 13.3 (19.3) | 11.1–15.6 | 64.8 | 4.7 |

| Insomnia | 1 | 31.5 (29.3) | 28.3–35.0 | 35.9 | 25.0 |

| Appetite loss | 1 | 16.9 (24.7) | 14.1–19.9 | 62.5 | 11.7 |

| Constipation | 1 | 26.3 (30.3) | 22.8–30.2 | 48.4 | 21.9 |

| Diarrhoea | 1 | 10.2 (18.5) | 7.8–12.5 | 73.4 | 3.1 |

| Financial difficulties | 1 | 51.6 (37.0) | 47.1–56.1 | 24.2 | 53.9 |

| QLQ-CX24 Functional scales d | |||||

| Body image | 3 | 25.1 (22.9) | 22.3–27.9 | 86.7 | 13.3 |

| Sexual activity | 1 | 8.3 (15.6) | 6.4–10.3 | 96.7 | 3.3 |

| Sexual enjoyment | 1 | 77.8 (25.0) | 71.7–82.9 | 72.7 | 25.0 |

| Sexual/vaginal functioning | 4 | 75.5 (22.9) | 69.6–80.3 | 73.4 | 23.4 |

| QLQ-CX24 Symptom scales c | |||||

| Symptom experience | 11 | 14.2 (12.4) | 12.8–15.7 | 92.2 | 0.8 |

| Lymphoedema | 1 | 8.8 (18.9) | 6.8–11.3 | 78.9 | 4.7 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1 | 22.4 (24.0) | 19.7–25.5 | 46.1 | 11.7 |

| Menopausal symptoms | 1 | 21.6 (24.5) | 18.7–24.7 | 49.2 | 12.5 |

| Sexual worry | 1 | 10.4 (19.9) | 8.2–13.0 | 73.4 | 2.3 |

aFor functional scales, subjects scoring <33.3% have problems; those scoring ≥66.7% have good functioning. For symptom scales/symptoms, subjects scoring <33.3% have good functioning; those scoring = 66.7% have problems. bFor functional scales, higher scores indicate better functioning. cFor symptom scales, higher scores indicate worse functioning. dHigher scores indicate worse functioning, except for Sexual activity and Sexual enjoyment.

QOL characteristics of patients according to socio-demographic variables

Age

Statistically significant and clinically relevant difference was found in two scales of QLQ-CX24; vaginal sexual functioning and peripheral neuropathy were more problematic among the age group of over 46 years. Dyspnea (p = 0.000), and sexual worry (p = 0.002) were significant among the patients under 45 years (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality of life score by age, education, and residence of the patients.

| QLQ Items | Age | P | Clrel* | Education | P | Clrel* | Residence | P | Clrel* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤45 | ≥46 | Illiterate | Literate | Rural | Urban | |||||||

| N = 66 | N = 190 | N = 56 | N = 200 | N = 126 | N = 130 | |||||||

| C30 Functional scales | ||||||||||||

| Global health status/ QOL | 68.7 ± 25.0 | 64.1 ± 22.2 | 0.073 | No | 53.5 ± 23.4 | 68.5 ± 21.8 | 0.000 | Yes | 55.1 ± 24.9 | 73.3 ± 18.6 | 0.000 | Yes |

| Physical functioning | 86.9 ± 22.2 | 83.4 ± 17.6 | 0.291 | No | 79.5 ± 19.0 | 85.6 ± 15.8 | 0.042 | No | 80.6 ± 21.3 | 86.5 ± 14.8 | 0.178 | No |

| Role functioning | 86.4 ± 16.8 | 83.7 ± 24.0 | 0.942 | No | 82.1 ± 24.2 | 85.0 ± 21.8 | 0.367 | No | 81.1 ± 23.6 | 84.4 ± 23.0 | 0.231 | No |

| Emotional functioning | 81.3 ± 15.3 | 79.9 ± 19.1 | 0.984 | No | 79.4 ± 20.7 | 80.5 ± 17.4 | 0.907 | No | 78.2 ± 20.8 | 81.4 ± 15.9 | 0.595 | No |

| Cognitive functioning | 83.8 ± 15.7 | 78.8 ± 20.3 | 0.139 | No | 78.6 ± 20.0 | 70.5 ± 18.8 | 0.651 | No | 79.2 ± 19.2 | 80.4 ± 20.4 | 0.553 | No |

| Social functioning | 75.2 ± 24.5 | 69.3 ± 27.7 | 0.158 | No | 58.3 ± 33.6 | 74.3 ± 24.2 | 0.001 | Yes | 59.1 ± 0.8 | 74.8 ± 22.5 | 0.001 | Yes |

| Symptom scales | ||||||||||||

| Fatigue | 22.6 ± 16.2 | 25.6 ± 20.6 | 0.470 | No | 25.8 ± 18.9 | 24.5 ± 19.7 | 0.352 | No | 25.5 ± 22.0 | 25.4 ± 18.0 | 0.696 | No |

| Nausea & vomiting | 11.1 ± 14.7 | 16.8 ± 24.5 | 0.365 | No | 20.8 ± 25.7 | 13.8 ± 21.4 | 0.040 | No | 20.8 ± 26.5 | 13.3 ± 22.5 | 0.023 | No |

| Pain | 17.2 ± 15.2 | 17.9 ± 22.2 | 0.411 | No | 22.0 ± 24.2 | 16.5 ± 19.4 | 0.233 | No | 21.6 ± 25.9 | 15.2 ± 19.3 | 0.179 | No |

| Dyspnoea | 20.2 ± 20.1 | 10.9 ± 18.4 | 0.000 | No | 9.5 ± 15.1 | 14.3 ± 20.1 | 0.165 | No | 10.6 ± 17.1 | 15.5 ± 21.9 | 0.164 | No |

| Insomnia | 26.2 ± 28.5 | 33.3 ± 29.5 | 0.069 | No | 29.8 ± 28.9 | 32.0 ± 29.5 | 0.643 | No | 26.5 ± 27.3 | 31.8 ± 27.3 | 0.174 | No |

| Appetite loss | 11.1 ± 19.7 | 18.9 ± 25.9 | 0.033 | No | 28.5 ± 28.0 | 13.7 ± 22.7 | 0.000 | Yes | 20.4 ± 26.9 | 14.8 ± 26.0 | 0.116 | No |

| Constipation | 20.2 ± 24.7 | 28.4 ± 31.7 | 0.750 | No | 32.1 ± 34.2 | 24.7 ± 28.9 | 0.174 | No | 28.8 ± 32.4 | 23.7 ± 30.5 | 0.291 | No |

| Diarrhoea | 12.1 ± 23.1 | 9.5 ± 16.5 | 0.748 | No | 8.3 ± 14.5 | 10.7 ± 19.4 | 0.655 | No | 8.3 ± 14.5 | 14.8 ± 22.9 | 0.079 | No |

| Financial difficulties | 46.5 ± 35.0 | 53.3 ± 37.7 | 0.179 | No | 67.8 ± 38.6 | 47.0 ± 35.4 | 0.000 | Yes | 72.7 ± 32.2 | 42.2 ± 36.3 | 0.000 | Yes |

| CX24 Functional scales | ||||||||||||

| Body image | 21.5 ± 21.7 | 26.3 ± 23.1 | 0.118 | No | 29.4 ± 25.5 | 23.9 ± 21.9 | 0.192 | No | 24.7 ± 23.3 | 24.4 ± 21.6 | 0.888 | No |

| Sexual activity | 8.5 ± 15.8 | 8.2 ± 15.6 | 0.863 | No | 4.2 ± 11.1 | 9.5 ± 16.4 | 0.027 | No | 7.6 ± 14.9 | 8.5 ± 16.2 | 0.756 | No |

| Sexual enjoyment (n = 80) | 70.4 ± 19.4 | 80.2 ± 26.3 | 0.199 | No | 55.6 ± 40.8 | 68.1 ± 41.2 | 0.191 | No | 55.5 ± 36.1 | 70.2 ± 45.0 | 0.018 | Yes |

| Sexual/vaginal functioning (n = 72) | 86.1 ± 13.4 | 71.9 ± 24.3 | 0.025 | Yes | 87.5 ± 14.8 | 73.9 ± 23.4 | 0.099 | No | 76.0 ± 14.5 | 71.1 ± 28.6 | 0.865 | No |

| Symptom scales | ||||||||||||

| Symptom experience | 10.5 ± 7.5 | 15.9 ± 13.6 | 0.013 | No | 15.9 ± 12.5 | 13.7 ± 12.4 | 0.209 | No | 17.1 ± 12.0 | 15.4 ± 15.2 | 0.083 | No |

| Lymphoedema | 10.1 ± 19.4 | 8.4 ± 18.7 | 0.457 | No | 11.9 ± 22.4 | 8.0 ± 17.7 | 0.147 | No | 15.9 ± 24.2 | 3.7 ± 12.7 | 0.000 | Yes |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 14.1 ± 18.5 | 25.3 ± 25.0 | 0.002 | Yes | 26.2 ± 27.5 | 21.3 ± 22.9 | 0.310 | No | 26.5 ± 27.3 | 19.2 ± 22.9 | 0.081 | No |

| Menopausal symptoms | 24.2 ± 27.7 | 20.7 ± 23.3 | 0.510 | No | 20.2 ± 24.4 | 22.0 ± 24.6 | 0.614 | No | 25.0 ± 25.9 | 20.0 ± 24.9 | 0.158 | No |

| Sexual worry | 14.1 ± 16.6 | 9.1 ± 20.8 | 0.002 | No | 3.6 ± 10.4 | 12.3 ± 21.5 | 0.002 | No | 8.3 ± 19.0 | 13.3 ± 23.8 | 0.101 | No |

*Clinical relevance ≥10 points differences.

Education

Literate patients had good global/QOL (p = 0.000, clinically relevant) and social functioning (p = 0.001, clinically relevant), physical functioning (p = 0.042). Illiterate patient’s data showed more appetite loss, more financial difficulties (p = 0.000, clinically relevant) and more nausea/vomiting (p = 0.040) (Table 2).

Residence

Patients living in an urban area showed better global/QOL (p = 0.000, clinically relevant), good social functioning (p = 0.001, clinically relevant). Patients living in a rural area reported financial difficulties (p = 0.000, clinically relevant), problems in sexual enjoyment (p = 0.018, clinically relevant), and lymphoedema (p = 0.000, clinically relevant) (Table 2).

Occupation

Service holder showed good global QOL. However, retired/unemployed/housewife group of patients had good social functioning (p = 0.000, clinically relevant) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Quality of life score according to occupation and family annual income.

| QLQ Items | Occupation | P | Clrel* | Family income | P | Clrel* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Employed | Othersa | ≤1450 USD | >1451 USD | |||||

| N = 88 | N = 90 | N = 78 | N = 112 | N = 144 | |||||

| C30 Functional scales | |||||||||

| Global health status/ QOL | 55.1 ± 24.9 | 73.3 ± 18.7 | 67.5 ± 21.1 | 0.000 | Yes | 57.7 ± 25.0 | 71.2 ± 19.4 | 0.000 | Yes |

| Physical functioning | 80.6 ± 21.3 | 86.5 ± 14.8 | 85.8 ± 11.9 | 0.398 | No | 82.4 ± 19.2 | 85.7 ± 14.5 | 0.496 | No |

| Role functioning | 81.9 ± 22.0 | 84.4 ± 23.0 | 88.0 ± 19.7 | 0.107 | No | 80.6 ± 24.2 | 87.3 ± 20.4 | 0.017 | No |

| Emotional functioning | 78.2 ± 20.8 | 81.4 ± 15.9 | 81.2 ± 19.7 | 0.775 | No | 78.1 ± 9.2 | 81.9 ± 17.3 | 0.136 | No |

| Cognitive functioning | 79.2 ± 19.3 | 80.4 ± 20.4 | 80.8 ± 18.2 | 0.817 | No | 78.6 ± 19.6 | 81.2 ± 18.9 | 0.266 | No |

| Social functioning | 59.1 ± 30.8 | 74.8 ± 22.5 | 79.5 ± 22.3 | 0.000 | Yes | 60.4 ± 28.9 | 78.9 ± 22.3 | 0.000 | Yes |

| C30 Symptom scales | |||||||||

| Fatigue | 25.5 ± 22.0 | 25.4 ± 18.0 | 23.4 ± 18.4 | 0.683 | No | 27.6 ± 21.4 | 22.7 ± 17.7 | 0.094 | No |

| Nausea & vomiting | 20.8 ± 26.5 | 13.3 ± 22.5 | 11.5 ± 15.7 | 0.037 | No | 16.7 ± 24.5 | 14.3 ± 20.9 | 0.591 | No |

| Pain | 21.6 ± 25.9 | 15.2 ± 19.3 | 16.2 ± 13.9 | 0.322 | No | 19.3 ± 24.0 | 16.4 ± 17.5 | 0.917 | No |

| Dyspnoea | 10.6 ± 17.2 | 15.5 ± 21.9 | 13.7 ± 16.2 | 0.325 | No | 13.1 ± 19.7 | 13.4 ± 19.0 | 0.785 | No |

| Insomnia | 26.5 ± 27.3 | 31.8 ± 27.3 | 36.7 ± 32.9 | 0.126 | No | 29.7 ± 28.8 | 32.9 ± 29.7 | 0.394 | No |

| Appetite loss | 20.4 ± 26.9 | 14.8 ± 26.0 | 15.4 ± 19.9 | 0.255 | No | 17.3 ± 25.3 | 16.7 ± 24.3 | 0.956 | No |

| Constipation | 28.8 ± 32.4 | 23.7 ± 30.5 | 26.5 ± 27.6 | 0.484 | No | 29.2 ± 31.0 | 24.1 ± 29.6 | 0.170 | No |

| Diarrhoea | 8.3 ± 14.5 | 14.8 ± 22.9 | 6.8 ± 15.5 | 0.025 | No | 12.5 ± 20.6 | 8.3 ± 16.5 | 0.078 | No |

| Financial difficulties | 72.7 ± 32.2 | 42.2 ± 36.3 | 38.5 ± 32.7 | 0.000 | Yes | 68.5 ± 32.5 | 38.4 ± 35.1 | 0.000 | Yes |

| CX24 Functional scales | |||||||||

| Body image | 24.7 ± 23.3 | 24.4 ± 21.6 | 26.2 ± 24.1 | 0.912 | No | 24.9 ± 24.4 | 25.2 ± 21.7 | 0.640 | No |

| Sexual activity | 7.5 ± 14.9 | 8.5 ± 16.2 | 8.9 ± 15.8 | 0.831 | No | 6.5 ± 14.7 | 9.7 ± 16.2 | 0.071 | No |

| Sexual enjoyment (n = 80) | 55.5 ± 36.1 | 70.2 ± 45.0 | 69.4 ± 37.9 | 0.052 | No | 55.6 ± 41.3 | 72.3 ± 40.1 | 0.021 | Yes |

| Sexual/vaginal functioning (n = 72) | 76.0 ± 14.5 | 71.1 ± 28.6 | 81.8 ± 16.2 | 0.465 | No | 75.7 ± 27.9 | 75.3 ± 20.3 | 0.493 | No |

| CX24 Symptom scales | |||||||||

| Symptom experience | 17.1 ± 12.1 | 15.4 ± 15.3 | 9.5 ± 6.6 | 0.000 | No | 15.6 ± 11.1 | 13.1 ± 13.2 | 0.010 | No |

| Lymphoedema | 15.9 ± 24.2 | 3.7 ± 12.7 | 6.8 ± 15.5 | 0.000 | Yes | 10.7 ± 19.0 | 7.4 ± 18.7 | 0.058 | No |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 26.5 ± 27.3 | 19.2 ± 22.9 | 21.4 ± 20.8 | 0.196 | No | 23.8 ± 25.8 | 21.3 ± 22.5 | 0.590 | No |

| Menopausal symptoms | 25 ± 25.9 | 20.0 ± 24.9 | 19.6 ± 22.4 | 0.296 | No | 23.2 ± 24.4 | 20.4 ± 24.6 | 0.278 | No |

| Sexual worry | 8.3 ± 19.0 | 13.3 ± 23.8 | 9.4 ± 15.1 | 0.250 | No | 8.9 ± 18.4 | 11.6 ± 20.9 | 0.278 | No |

*Clinical relevance ≥10 points differences. aUnemployed/retired/housewife.

Family income

Patients with an annual family income more than US $1451 showed better global/QOL (p = 0.000, clinically relevant), better social functioning (p = 0.034, clinically relevant) and role functioning (p = 0.003) than with the lower income group (Table 3).

Stage of cancer

Table 4 showed that patients diagnosed in stage I had better global/QOL, better physical (p = 0.003), role (p = 0.003), social functioning (p = 0.034); more problems like fatigue (p = 0.036), nausea and vomiting (p = 0.009), appetite loss (p = 0.000) and financial difficulties (p = 0.000) were experienced by patients diagnosed in stage IV. These all findings were clinically relevant (Table 4).

Table 4.

Quality of life score according to the stage of cervical cancer and treatment modalities.

| QLQ Items | Stage | P | Clrel* | Treatment | P | Clrel* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | Surgery | S + C + R | C/R | |||||

| N = 103 | N = 119 | N = 20 | N = 14 | N = 60 | N = 137 | N = 59 | |||||

| C30 Functional scales | |||||||||||

| Global health status/ QOL | 70.5 ± 21.8 | 66.1 ± 21.0 | 55.8 ± 24.2 | 33.3 ± 17.9 | 0.000 | Yes | 75.8 ± 18.6 | 66.8 ± 22.9 | 51.1 ± 20.6 | 0.000 | Yes |

| Physical functioning | 87.7 ± 21.8 | 83.5 ± 22.1 | 85.0 ± 20.9 | 66.7 ± 24.4 | 0.003 | Yes | 89.8 ± 16.9 | 83.0 ± 16.0 | 81.6 ± 17.4 | 0.000 | No |

| Role functioning | 87.7 ± 21.8 | 83.5 ± 22.1 | 85.0 ± 20.9 | 66.7 ± 24.4 | 0.003 | Yes | 91.7 ± 16.1 | 82.7 ± 24.0 | 80.8 ± 22.5 | 0.003 | Yes |

| Emotional functioning | 79.5 ± 18.9 | 81.4 ± 16.9 | 80.8 ± 20.2 | 75.0 ± 21.2 | 0.714 | No | 79.4 ± 19.9 | 80.6 ± 17.3 | 80.2 ± 18.6 | 0.991 | No |

| Cognitive functioning | 80.7 ± 17.2 | 79.4 ± 20.5 | 85.0 ± 19.4 | 73.8 ± 22.4 | 0.413 | No | 81.1 ± 19.9 | 78.1 ± 19.2 | 83.6 ± 18.4 | 0.124 | No |

| Social functioning | 76.4 ± 25.3 | 68.9 ± 25.8 | 61.7 ± 31.6 | 59.5 ± 34.4 | 0.034 | Yes | 81.7 ± 21.8 | 70.9 ± 25.6 | 59.6 ± 30.5 | 0.000 | Yes |

| C30 Symptom scales | |||||||||||

| Fatigue | 22.6 ± 21.7 | 24.6 ± 16.4 | 28.9 ± 21.1 | 36.5 ± 22.8 | 0.036 | Yes | 20.4 ± 22.2 | 25.7 ± 19.0 | 27.3 ± 17.3 | 0.014 | No |

| Nausea & vomiting | 9.2 ± 15.2 | 18.3 ± 24.3 | 20.0 ± 25.1 | 28.6 ± 35.5 | 0.009 | Yes | 6.7 ± 16.0 | 14.5 ± 17.8 | 26.3 ± 32.0 | 0.000 | Yes |

| Pain | 15.8 ± 22.4 | 17.9 ± 18.3 | 23.3 ± 20.5 | 21.4 ± 25.7 | 0.166 | No | 11.1 ± 20.9 | 18.4 ± 19.4 | 22.9 ± 21.6 | 0.000 | Yes |

| Dyspnoea | 11.6 ± 18.5 | 15.1 ± 19.8 | 6.7 ± 13.7 | 19.0 ± 25.1 | 0.174 | No | 6.7 ± 16.0 | 16.0 ± 20.2 | 13.6 ± 18.7 | 0.003 | No |

| Insomnia | 31.7 ± 31.1 | 30.2 ± 28.4 | 30.0 ± 23.9 | 42.8 ± 30.4 | 0.446 | No | 25.6 ± 22.4 | 31.6 ± 32.7 | 37.3 ± 26.3 | 0.077 | No |

| Appetite loss | 8.7 ± 18.6 | 19.3 ± 23.1 | 26.7 ± 29.8 | 42.8 ± 40.1 | 0.000 | Yes | 4.4 ± 11.4 | 18.5 ± 25.2 | 25.9 ± 28.4 | 0.000 | Yes |

| Constipation | 19.7 ± 28.2 | 29.4 ± 30.1 | 36.7 ± 32.3 | 33.3 ± 36.9 | 0.016 | Yes | 15.6 ± 28.4 | 27.7 ± 29.0 | 33.9 ± 32.4 | 0.001 | Yes |

| Diarrhoea | 7.8 ± 15.6 | 10.0 ± 16.5 | 16.7 ± 31.5 | 19.0 ± 25.2 | 0.221 | No | 4.4 ± 11.4 | 10.4 ± 18.4 | 15.2 ± 22.6 | 0.006 | Yes |

| Financial difficulties | 41.1 ± 35.6 | 55.2 ± 35.9 | 63.3 ± 35.7 | 80.9 ± 36.3 | 0.000 | Yes | 33.3 ± 36.8 | 54.2 ± 33.6 | 63.8 ± 38.8 | 0.000 | Yes |

| CX24 Functional scales | |||||||||||

| Body image | 22.9 ± 23.9 | 26.0 ± 22.3 | 31.1 ± 25.4 | 24.6 ± 14.6 | 0.286 | No | 22.4 ± 23.5 | 25.1 ± 21.2 | 27.9 ± 25.8 | 0.391 | No |

| Sexual activity | 7.1 ± 15.9 | 8.9 ± 15.5 | 6.7 ± 13.7 | 14.3 ± 17.1 | 0.216 | No | 7.2 ± 16.3 | 8.2 ± 15.0 | 9.6 ± 16.4 | 0.561 | No |

| Sexual enjoyment (n = 80) | 73.0 ± 35.5 | 52.4 ± 50.8 | 83.3 ± 19.2 | 77.8 ± 17.2 | 0.334 | No | 74.5 ± 33.9 | 58.1 ± 47.3 | 69.7 ± 37.9 | 0.429 | No |

| Sexual/vaginal functioning (n = 72) | 75.4 ± 26.2 | 69.7 ± 17.5 | 95.8 ± 4.8 | 83.3 ± 14.9 | 0.054 | No | 85.9 ± 13.9 | 60.0 ± 24.4 | 88.3 ± 13.1 | 0.000 | Yes |

| CX24 Symptom scales | |||||||||||

| Symptom experience | 12.7 ± 9.3 | 15.6 ± 15.1 | 14.2 ± 10.5 | 13.2 ± 9.0 | 0.901 | No | 10.9 ± 7.1 | 14.9 ± 14.0 | 15.7 ± 12.4 | 0.161 | No |

| Lymphoedema | 8.4 ± 20.7 | 8.9 ± 17.2 | 6.7 ± 13.7 | 14.3 ± 25.2 | 0.654 | No | 10.0 ± 21.5 | 8.7 ± 18.6 | 7.9 ± 16.8 | 0.974 | No |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 21.4 ± 21.3 | 24.1 ± 24.9 | 16.7 ± 17.0 | 23.8 ± 40.1 | 0.582 | No | 20.0 ± 23.9 | 23.8 ± 22.8 | 21.5 ± 26.8 | 0.345 | No |

| Menopausal symptoms | 24.6 ± 27.6 | 21.3 ± 22.4 | 13.3 ± 16.7 | 14.3 ± 25.2 | 0.221 | No | 22.2 ± 27.9 | 22.9 ± 23.8 | 18.1 ± 22.6 | 0.400 | No |

| Sexual worry | 16.2 ± 20.3 | 5.0 ± 16.0 | 16.7 ± 31.5 | 4.7 ± 12.1 | 0.000 | Yes | 14.4 ± 16.6 | 8.2 ± 17.5 | 11.3 ± 26.7 | 0.007 | No |

*Clinical relevance ≥10 points differences; S + C + R: surgery + chemotherapy + radiotherapy; C/R: chemotherapy and or radiotherapy.

Treatment modalities

Patients who underwent surgery showed better global/QOL (p = 0.000, clinically relevant), better role (p = 0.003, clinically relevant), and social functioning (p = 0.000). Regarding symptom scales patients with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy tend to have more problem with nausea and vomiting (p = 0.000), pain (p = 0.000), appetite loss (p = 0.000), constipation (p = 0.001), diarrhea (p = 0.006), and financial difficulties (p = 0.000), which were clinically relevant too (Table 4).

Time since diagnosis

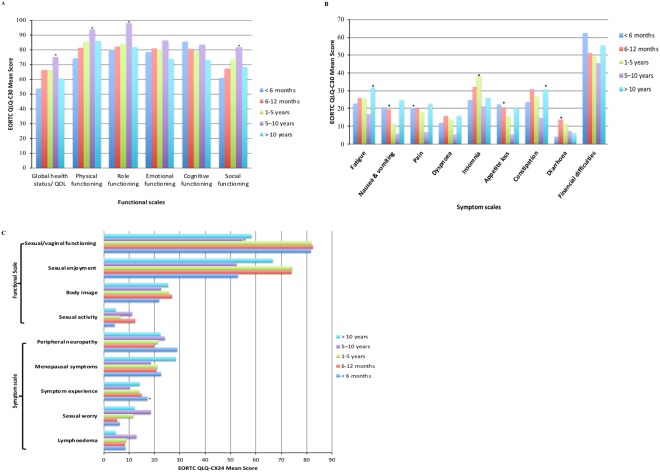

Patients with 5 to 10 years of survival reported good global QOL, physical, role, social and sexual and vagina functioning (p < 0.05, clinically relevant). However, most symptoms, pain (p = 0.006, clinically relevant), nausea/vomiting (p = 0.003, clinically relevant) and appetite loss (p = 0.015, clinically relevant), were experienced within 12 months. Patients who were diagnosed more than ten years reported more fatigue (p = 0.045, clinically relevant) and constipation (p = 0.041, clinically relevant) symptoms (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Quality of life scores of cervical cancer patients according to time since diagnosis. (A) EORTC QLQ-C30- functional scores. (B) EORTC QLQ-C30- symptoms scores (C). EORTC QLQ-CX24 scores.

Multiple linear regressions

Table 5 presents the association between overall QOL and different variables related to patient and treatment. It shows that lower family income, the rural area of living had a negative impact on the overall QOL, and the advanced stage of cancer had a statistically significant effect on overall QOL of patients (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multiple linear regression of overall QOL.

| Variables | Unstandardized coefficients (B) | Coefficients (Beta) | t-statistics | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 52.435 | 4.043 | 0.000 | |

| Age | 1.578 | 0.027 | 0.397 | 0.692 |

| Family annual income | 10.741 | 0.225 | 2.862 | 0.005 |

| Stage of cancer | −7.666 | −0.273 | −3.326 | 0.001 |

| Treatment modality | −2.846 | −0.088 | −1.072 | 0.285 |

| Time since diagnosis | −0.346 | −0.017 | −0.253 | 0.800 |

| Residence | 8.120 | 0.171 | 1.999 | 0.047 |

| Education status | 0.647 | 0.012 | 0.151 | 0.880 |

Note: Adjusted R2 = 0.29.

Discussion

The characteristics of patients with CC and QOL after treatment was the focus of this study. More than half of the patients with CC reported an excellent QOL, similar to the most published data21,27. Consistent with our finding, the study reported that global health status of CC patients was 59.5 ± 10.9 in India28. Regarding functional dimension, the patients reported proper functioning in overall scales (score range: 70.8 ± 26.9 to 91.7 ± 15.6) except for sexual enjoyment and sexual or vaginal functioning. The higher scores might be because nearly 60% of the patients enrolled in our study had early-stage cancer (stage IA-IIA). The adverse symptoms experienced mostly were insomnia, constipation, appetite loss, financial difficulty, menopausal symptoms and peripheral neuropathy. These findings are resembling other similar studies10,21.

Patient’s lower annual family income and rural area of living showed a negative impact on global QOL. Reports indicate that less education had been associated with limited knowledge about health issues and poor health10,21. Cancer survivors living in the rural area are at higher risk for a variety of poor health outcomes29 and poor socioeconomic status (e.g., lower education level and income) are less likely to have follow-up care with providers leading to poor health outcome27,30. Patients from a rural area or with lower economic status or illiterate people might be unaware of cervical cancer. So, these individuals may usually reach the hospital with the late stage of cancer, which leads to poor treatment outcome and consequently a reduced quality of life. Therefore, these problems should be given due attention by the concerned authority to improve the QOL.

Younger patients reported better functional scales than older age groups which are similar to the study result reported by the Action Study Group27. Wenzel et al. reported that younger CC patients experience a persistent detrimental effect on their QOL31. Several studies reported a negative impact of sexuality across all CC patients24,32–34. Young patients in our study had reported more sexual worry compared to an older group of patients. In line with our study, the previous research said younger patients were concerned with fertility, femininity, treatment-related menopause, and relationship issues35. Cervical cancer is known as the human papillomavirus (HPV) related cancer, and a positive high-risk HPV regarded as a sexually transmitted infection (STI). Young people are sexually active, so the chances of having STI is also higher among those who have risky sexual behavior; on the other hand, they have access to the information about STI or HPV which might be partially correct. Therefore, many young women especially the educated patients might blame their husband or partner for the disease, which leads to relationship problems and causes more sexual worry. Many studies reported a negative impact on sexuality among patients with CC and its treatment21,34,36. These findings underline the importance of counseling regarding these problems, especially with younger and educated patients about the right information of high-risk HPV infection and the existence of all other co-factors as well.

Sexuality is an essential aspect of gynecological cancer, thus being a crucial determinant of QOL. In the present study, there was a significant decrease in sexual enjoyment and the sexual and vaginal functioning score. Previous reports also stated that 40% to 100% of individuals face sexual dysfunction after treatments because CC and its treatment affect the same areas of the body that are involved in sexual response10,37. Patients with surgery along with chemotherapy and radiotherapy reported worse in sexual and vaginal functioning than those with surgery. Sexual dysfunction from surgery is mainly due to the shortened vagina, vaginal dryness, decreased libido38,39. However, after radiotherapy, sexual dysfunction is caused by vaginal stenosis which leads to dyspareunia, difficulty in orgasm, a decrease in sexual satisfaction, and changes in body image40.

Patients who had undergone radiotherapy and chemotherapy had experienced more symptoms like fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea and financial difficulty than those who underwent surgery only. Many studies have mentioned that radiotherapy to the pelvic cavity has easily caused intestinal dysfunctions41. Radiation has also created lactose and bile salt malabsorption, intestinal bacteria imbalance and altered intestinal peristalsis. Therefore, radiotherapy for CC often causes intestinal dysfunctions42,43.

The advanced stage of cancer showed a negative impact on global QOL and patients with early-stage cancer reported better QOL. Several studies reported that, for global health status or overall QOL, patients with stage I, II, and III of cancer have higher QOL compared to stage IV10,44. Regarding role functioning, patients in stage I had the better QOL followed by stage II; stage IV had the worse role functioning. Patients at the late stage of cancer would have poor role functioning as these patients usually planned for palliative management and therefore unable to perform much work.

Also, time since diagnosis affects the self-reported health status and QOL among cancer survivors9. The present study findings are consistent that time is a significant factor in QOL of survivors. Patients diagnosed for 5 to 10 years reported higher scores on global QOL, physical functioning, role functioning and sexual and vaginal functioning. However, after ten years since diagnosis, the functional scale (global QoL, physical, role, social and sexual and vaginal functioning) scores were decreasing than in the 5–10 years’ period and also nearly similar to the time of 6–12 months after diagnosis. Similarly, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain and constipation symptoms were increased with more than ten years of survivorship. These findings could be the result of the long-term effect of chemotherapy and radiotherapy that patients experience bowel, bladder, and sexual dysfunction even after many years of treatment is in line with another study45. To improve the health outcome of CC patients the treatment and management should focus on time since diagnosis as well. Patients need long-term care for better health outcome. This finding suggests that the QOL of the patient is changing over the long term. Further study is recommended to evaluate the QOL of long-term survivors.

Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. The QOL of cancer survivors changes over time. As this is a cross-sectional design, the assessment of QOL was not done over time, and the lack of the comparison of QOL score before and after treatment contribute to the limitations. The data collection was limited to a single institution based so the study results could not be generalized to the whole population of cancer survivors in China. However, the study contributes to how to improve patient care and further research for women with CC in China. Longitudinal and intervention studies with control group may better evaluate the QOL of CC survivors.

Conclusion

More than half of the patients with cervical cancer reported an excellent QOL. The rural area of living and poor economic status of the patients with cervical cancer has a negative impact on overall quality of life. Younger and educated patients are more worried about sexuality and patients treated with multiple therapies had more problems with their QOL scales than patients treated with surgery only.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Caixia Zhang, Hui Qiu, Mengfei Xu for their support to conduct this study and special thanks go to the study participants.

Author Contributions

N.T., M.M., and H.B.C. conceptualized and designed the study. N.T., T.P.N., Y.X., and D.Q.J. performed the data collection. M.A.P., M.M., N.T., and T.P.N. conducted the data analysis, interpretation, and manuscript writing. H.B.C., Y.X., D.Q.J., and M.P. critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Niresh Thapa and Muna Maharjan contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-30506-6.

References

- 1.Ferlay, J. et al. GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. GLOBOCAN 2012v1.0 at http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx (2013).

- 2.Chen W, et al. Cancer Statistics in China. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016;66:115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai HB, et al. Trends in cervical cancer in young women in Hubei, China. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2010;20:1. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181ecec79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang L, et al. Prevalence and type distribution of high-risk human papillomavirus infections among women in Wufeng County, China. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012;286:695–699. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guideline in Oncology: Cervical cancer, 10.1017/CBO9781139046947.057 (2016).

- 6.Zhou W, et al. Survey of cervical cancer survivors regarding quality of life and sexual function. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2016;12:938–944. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.157353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye S, Yang J, Cao D, Lang J, Shen K. A systematic review of quality of life and sexual function of patients with cervical cancer after treatment. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2014;24:1146–1157. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinten C, et al. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:865–871. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim M-K, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life and Sociodemographic Characteristics as Prognostic Indicators of Long-term Survival in Disease-Free Cervical Cancer Survivors. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2016;26:743–749. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park SY, et al. Quality of life and sexual problems in disease-free survivors of cervical cancer compared with the general population. Cancer. 2007;110:2716–2725. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guideline in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Cervical cancer. NCCN, 10.1017/CBO9781139046947.057 (2018).

- 12.Fayers, P. et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. (EORTC, 2001).

- 13.Hua CH, et al. Validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer cervical cancer module for Chinese patients with cervical cancer. Patient Prefer. Adherence. 2013;7:1061–1066. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S52498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wan C, et al. Validation of the simplified Chinese version of EORTC QLQ-C30 from the measurements of five types of inpatients with cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2008;19:2053–2060. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greimel ER, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality-of-Life questionnaire cervical cancer module: EORTC QLQ-CX24. Cancer. 2006;107:1812–1822. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayasekara H, Rajapaksa LC, Greimel ER. The EORTC QLQ-CX24 cervical cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire: psychometric properties in a South Asian sample of cervical cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2008;17:1053–1057. doi: 10.1002/pon.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paradowska D, et al. Validation of the Polish version of the EORTC QLQ-CX24 module for the assessment of health-related quality of life in women with cervical cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23:214–220. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin DW, et al. Cross-Cultural Application of the Korean Version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Cervical Cancer Module. Oncology. 2009;76:190–198. doi: 10.1159/000201571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer S, et al. Patients’ acceptance and psychometric properties of the EORTC QLQ-CX24 after surgery. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010;116:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.du Toit GC, Kidd M. An analysis of the psychometric properties of the translated versions of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ CX24 questionnaire in the two South African indigenous languages of Xhosa and Afrikaans. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25:832–838. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang H-Y, et al. Quality of life of breast and cervical cancer survivors. BMC Womens. Health. 2017;17:30. doi: 10.1186/s12905-017-0387-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tax C, Steenbergen ME, Zusterzeel PLM, Bekkers RLM, Rovers MM. Measuring health-related quality of life in cervical cancer patients: a systematic review of the most used questionnaires and their validity. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017;17:15. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0289-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fayers, P. M. et al. EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. at http://www.forskningsdatabasen.dk/en/catalog/2192871649 (2001).

- 24.Bjelic-Radisic V, et al. Quality of life characteristics inpatients with cervical cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2012;48:3009–3018. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahn SH, et al. Health-related quality of life in disease-free survivors of breast cancer with the general population. Ann. Oncol. 2007;18:173–82. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osoba D. A taxonomy of the uses of health related-quality of life instruments in cancer care and the clinical meaningfulness of the results. Med. Care. 2002;40:III31–III38. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200206001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Action Study Group. Health-related quality of life and psychological distress among cancer survivors in Southeast Asia: results from a longitudinal study in eight low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med. 15, 10 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Dahiya N, et al. Quality of Life of Patients with Advanced Cervical Cancer before and after Chemoradiotherapy. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016;17:3095–3099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD. Rural-urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119:1050–1057. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DiMartino LD, Birken SA, Mayer DK. The Relationship Between Cancer Survivors’ Socioeconomic Status and Reports of Follow-up Care Discussions with Providers. J. Cancer Educ. 2017;32:749–755. doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1024-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenzel L, et al. Quality of life in long-term cervical cancer survivors. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005;97:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chia-Chun L, Ting-Chang C, Yun-Fang T, Lynn C. Quality of life among survivors of early-stage cervical cancer in Taiwan: an exploration of treatment modality differences. Qual. Life Res. 2017;26:2773–2782. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muliira R, Salas A, O’Brien B. Quality of life among female cancer survivors inAfrica: An integrative literature review. Asia-Pacific J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017;4:6. doi: 10.4103/2347-5625.199078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derks M, et al. Long-Term Morbidity and Quality of Life in Cervical Cancer Survivors. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2017;27:350–356. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan YM, et al. A longitudinal study on quality of life after gynecologic cancer treatment. Gynecol. Oncol. 2001;83:10–19. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sung UL, et al. General health status of long-term cervical cancer survivors after radiotherapy. Strahlentherapie und Onkol. 2017;193:543–551. doi: 10.1007/s00066-017-1143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar, S. et al. PrediQt-Cx: Post treatment health related quality of life prediction model for cervical cancer patients. PLoS One9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Burns M, Costello J, Ryan-Woolley B, Davidson S. Assessing the impact of late treatment effects in cervical cancer: An exploratory study of women’s sexuality: Original article. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl). 2007;16:364–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen PT, et al. Early-Stage Cervical Carcinoma, Radical Hysterectomy, and Sexual Function: A Longitudinal Study. Cancer. 2004;100:97–106. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buković D, et al. Sexual life after cervical carcinoma. Coll. Antropol. 2003;27:173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pieterse QD, et al. Self-reported sexual, bowel and bladder function in cervical cancer patients following different treatment modalities: Longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2013;23:1717–1725. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182a80a65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stacey R, Green JT. Radiation-induced small bowel disease: Latest developments and clinical guidance. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2013;5:15–29. doi: 10.1177/2040622313510730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steen R, Dahl AA, Hess SL, Kiserud CE. A study of chronic fatigue in Norwegian cervical cancer survivors. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017;146:630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie Y, et al. Assessment of quality of life for the patients with cervical cancer at different clinical stages. Chin. J. Cancer. 2013;32:275–282. doi: 10.5732/cjc.012.10047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pfaendler KS, Wenzel L, Mechanic MB, Penner KR. Cervical cancer survivorship: Long-term quality of life and social support HHS Public Access. Clin Ther. January. 2015;1:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.