Abstract

The abundance of organic carbon (OC) in vegetation and soils (~2,600 PgC) compared to carbon in the atmosphere (~830 PgC) highlights the importance of terrestrial OC in global carbon budgets. The residence time of OC in continental reservoirs, which sets the rates of carbon exchange between land and atmosphere, represents a key uncertainty in global carbon cycle dynamics. Retention of terrestrial OC can also distort bulk OC- and biomarker-based paleorecords, yet continental storage timescales remain poorly quantified. Using “bomb” radiocarbon (14C) from thermonuclear weapons testing as a tracer, we model leaf-wax fatty acid and bulk OC 14C signatures in a river-proximal marine sediment core from the Bay of Bengal in order to constrain OC storage timescales within the Ganges-Brahmaputra (G-B) watershed. Our model shows that 79–83% of the leaf-waxes in this core were stored in continental reservoirs for an average of 1,000–1,200 calendar years, while the remainder was stored for an average of 15 years. This age structure distorts high-resolution organic paleorecords across geologically rapid events, highlighting that compound-specific proxy approaches must consider storage timescales. Furthermore, these results show that future environmental change could destabilize large stores of old - yet reactive - OC currently stored in tropical basins.

Introduction

The age of terrestrial organic components in marine sediments reflects their residence times in continental reservoirs. Rivers supply OC with a spectrum of ages to the ocean, and distinct transport pathways impart unique ages to different higher plant-derived compound classes1–4. This study aims to quantify the storage history of a classic terrestrial biomarker compound class, leaf-wax fatty acids5, and, by extension, bulk terrestrial OC in the globally significant G-B river system. The G-B rivers drain the Himalayas and deliver 1–2 billion tons of sediment annually to the Bay of Bengal, building the world’s largest delta and submarine fan: the Bengal Fan6,7. The G-B river system is one of the largest outlets of terrestrial OC to the ocean, with 10–20% of annual terrestrial OC burial in global marine sediments occurring in the Bengal Basin8,9. The G-B rivers’ extensive catchment area (1.73 × 106 km2), steep topography, and seasonal monsoon lead to high sedimentation rates and efficient OC preservation in the Bengal Fan, where sediment effectively derives from a single source (the G-B rivers) and marine OC contributions are negligible8,10–12. Consequently, the Bengal Fan is an ideal location to generate high-resolution sedimentary records to study timescales of continental OC storage. While previous work has identified several components of the bulk OC possessing different sources and average ages within the G-B watershed3 (e.g., petrogenic C, bulk biospheric C, etc.), the age spectrum of the terrestrial OC, and more specifically leaf-wax fatty acids, delivered to the Bengal Fan has not been fully resolved and quantified.

An 18 m-long piston sediment core (SO188–336KL) was collected in 2006 at the head of the canyon that bisects the Bengal shelf13 (Supplementary Fig. S1). This core spans 1945 to 2006 CE according to age models derived from 137Cs records and correlation of storm-derived deposits with known cyclonic events (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). Consequently, this core captures the “bomb spike” derived from thermonuclear weapons testing, which was most active above ground in the 1950s and early 1960s. The core exhibits an exceptionally high average sedimentation rate of 30.5 cm/yr. Sedimentary units are composed of 2- to 15-cm thick, laminated sand and silt layers grading into finely laminated silty clay that are deposited during cyclone impacts of the inner shelf. Bulk geochemical data imply that the G-B rivers supply the fine-grained sediments deposited at the head of the canyon, and the sediment source was constant over the sampling interval (Supplemental Table S1)14,15. Large storm events could remobilize shelf-deposited sediment associated with older organic matter. Accordingly, the fine-grained (median grain size: 11–25 μm) upper units of the graded beds were selected for detailed geochemical analyses in order to avoid more heavily reworked sediment associated with coarser tempestite units.

This study focuses on saturated, even-numbered, straight-chained fatty acids, where the n-CX:0 fatty acid will be referred to as n-CX (x corresponds to the carbon chain length). The fatty acids from each sediment horizon exhibit a strong even-over-odd carbon number predominance (carbon preference index [CPI]: 3.7–4.2) with a biomodal distribution. The long-chain fatty acid (n-C24−32) concentrations dominate over the short-chain fatty acids, with the exception of n-C16 (Supplementary Fig. S6). The n-C24−32 δ13C values (−25.9 to −29.1‰) are comparable to those of n-C14, n-C16, and n-C22 fatty acids (−25.8 to −29.9‰) (Supplementary Fig. S7). In contrast, n-C18 and n-C20 fatty acids are shifted towards more 13C-enriched values (−23.4 to −27.8‰), consistent with increased marine plankton and/or freshwater algal inputs. The long-chain fatty acid distributions and δ13C values are characteristic of leaf-waxes from a mixed C3/C4 plant source5,16, which are consistent with previous findings17. The Bengal Fan long-chain fatty acid δ13C values are more comparable to fatty acids in the lower G-B river sediments than the Himalayan river sediments17,18, suggesting that floodplain fatty acids are preferentially exported over fatty acids sourced from the upland regions of the catchment area.

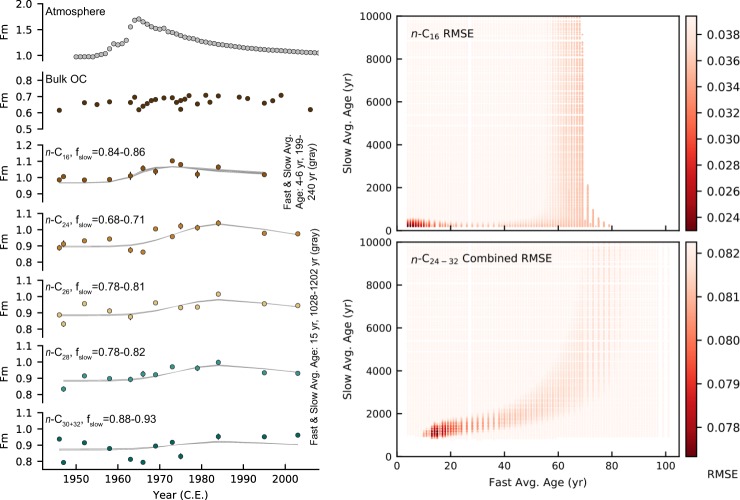

The radiocarbon time series show that the fatty acids incorporate bomb 14C (Fig. 1), where the data are expressed as the fraction of modern carbon, Fm (where 0 is radiocarbon-dead). The n-C16 fatty acid Fm peaks earlier than n-C24, n-C26, and n-C28. In contrast, n-C30+32 fatty acid does not display a clear bomb spike. The fatty acid Fm excursions are significantly smaller in magnitude and delayed in time relative to the atmospheric bomb spike. Fatty acids generally become more 14C-depleted with increasing chain length, which is consistent with previous studies2,19–21. Bulk OC is systematically more 14C-depleted than the corresponding fatty acids.

Figure 1.

Measured radiocarbon time series and fatty acid age structure modeling results. The measured 14C composition of bulk OC and fatty acids reported in Fm with 1σ error bars are plotted compared to the atmospheric radiocarbon composition in the northern hemisphere zone 326 (left). The heat maps (right) show how well each age structure fits the measured fatty acid Fm data according to RMSE. The color bars are scaled to bracket the RMSE values of the top 10% best-fitting age structures, where darker red represents better fits. Fast-cycling average ages exceeding 70–80 years are excluded for n-C16 because the optimal calculated fSlow is outside of the allowed range of 0 to 1. Note, that the modeling results shown for C24+ fatty acids are based on keeping the fast- and slow-cycling endmembers constant for all of the long-chain fatty acids. Synthetic Fm time series for the eight best-fitting age distributions are plotted in gray against the measured fatty acid Fm (left). The age distribution characteristics of the n-C16 and long-chain fatty acid synthetic Fm time series are described in the first and last rows of Table 1, respectively. See Figs. S9 and S10 for RMSE heat maps over the complete slow-cycling average age range (0–50,000 years) and additional synthetic Fm time series plots.

Bulk OC radiocarbon compositions average the ages of its many constituents, including the distinct ages carried by petrogenic carbon from bedrock erosion or by different classes of plant biomarkers, such as n-alkanes, fatty acids, and lignin derivatives1–3. In contrast, a narrow age distribution centered at the measured radiocarbon age is assumed in the traditional interpretation of compound-specific radiocarbon data owing to greater source specificity. However, recent research suggests that sedimentary compound-specific radiocarbon ages are more complex than previously thought4,22,23.

The muted bomb spikes recorded in the fatty acid radiocarbon records demonstrate that, despite source-specificity, each fatty acid homologue possesses a complex age distribution reflecting a diversity of storage and transport timescales4. The pre-bomb long-chain fatty acid radiocarbon ages range from 360 to 1,860 radiocarbon years. The atmospheric 14C signature is incorporated at the time of biosynthesis, starting the radiocarbon clock, which then decays during storage and remobilization on the path to deposition in marine sediments. If the fatty acids were hundreds to thousands of years old, as the radiocarbon ages suggest (i.e., the traditional interpretation), then the fatty acid time series would not record the 14C bomb spike because the vast majority of the fatty acid biosynthesis would have predated the initiation of nuclear weapons testing24. If the fatty acids were exported on annual timescales, the fatty acid time series would more closely mimic the atmospheric 14C record in magnitude and pacing24. The observed fatty acid Fm time series indicate that each homologue must have at least two constituents: a fast-cycling component that incorporates bomb carbon at a rate that depends on its turnover time, and a slow-cycling component that is insensitive to the atmospheric bomb spike. The slow-cycling component dilutes the isotopic excursion recorded in the fast-cycling component with the proportions of the two components varying among homologues.

According to this observation, a two-component isotope-mixing model was constructed to quantify the calendar ages and fractional contributions of the fast- and slow-cycling components for each fatty acid homologue, expressed as

| 1 |

and

| 2 |

where FmFA is the measured fatty acid Fm and FmFast, FmSlow, fFast, and fSlow are the Fm and the fractional abundances of the fast- and slow-cycling components.

To account for continental reservoirs that host OC with a smear of ages rather than a single discrete age or a combination of several discrete ages, the fast- and slow-cycling components are modeled as Gaussian age distributions that are described by the following probability distribution function:

| 3 |

where t is time, σ is the standard deviation, and μ is the center of the age distribution22,23. The atmospheric Fm sets the initial fatty acid radiocarbon composition, so the Fm of each component is expressed as a linear combination of sums of the atmospheric Fm (FmAtm) weighed by the probability distribution function both evaluated at time t. FmAtm is calculated from atmospheric Δ14C values from Intcal13 Northern Hemisphere25 and Northern Hemisphere zone 326 that are interpolated to yearly resolution and decayed for the time difference between time t and the sediment deposition year, t0. FmAtm values are set to 0 for years greater than 50,000 BP (i.e., radiocarbon-dead). The time domain is limited from t0 to 100,000 years BP (tmax), such that all of the fatty acids were biosynthesized before or during the year of sediment deposition. Accordingly, FmFast and FmSlow are calculated using the following equation:

| 4 |

where the denominator ensures that the distribution integrates to 1 after truncation of the time domain.

FmSlow and FmFast are calculated for each sample year for a range of age distributions (i.e., μ and σ). FmFast is calculated for 234 unique age distributions spanning average ages of 4 to 101 years. Likewise, FmSlow is calculated for 496 unique age distributions, spanning an average age range of 199 to > 50,000 years (i.e., radiocarbon-dead; FmSlow = 0). For each of the resulting 116,064 unique combinations of fast- and slow-cycling age distributions, the optimal fSlow for the entire FmFA time series is determined using a standard least squares regression solver implemented in the Python package Numpy (numpy.linalg.lstsq27). This calculation is performed independently for each homologue, and it assumes that the fast- and slow-cycling age structures (μ and σ) and their fractional contributions are constant over the sample interval 1946–2003. Next, the calculated fSlow, FmFast(t), and FmSlow(t) corresponding to each combination of fast- and slow-cycling distributions and for each homologue are substituted into Eqs (1) and (2) to generate synthetic fatty acid Fm time series. Finally, the root mean square error (RMSE) is calculated to determine the fit between the synthetic Fm data and the measured fatty acid data for each chain length. Fast- and slow-cycling age combinations are filtered out if the optimal fSlow was determined to be less than 0 or greater than 1.

RMSE heat maps (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S9) and Table 1 show which combinations of fast- and slow-cycling age distributions best fit the measured fatty acid radiocarbon data. n-C24, n-C26, and n-C28 share similar age distributions, while the best-fitting n-C30+32 age structure is older. Compared to the long-chain fatty acids, n-C16 has younger and narrower fast- and slow-cycling age distributions. The slow-cycling component contributes centennial carbon to n-C16 and a mixture of centennial and millennial carbon to the long-chain fatty acid inventory. The slow-cycling component represents a majority of every fatty acid homologue.

Table 1.

Summary of top eight best-fitting age distributions for individual fatty acids and combined long-chain fatty acids (Comb. n-C24−32) according to RMSE.

| FA | σFast (yrs) | σSlow (yrs) | μFast (yrs) | μSlow (yrs) | Fast Avg. Age (yrs) | Slow Avg. Age (yrs) | fSlow |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-C16 | 5–7.5 | 250 | 0–2 | 0–100 | 4–6 | 199–240 | 0.84–0.86 |

| n-C24 | 7.5 | 500–1250 | 12–15 | 0–1000 | 13–15 | 941–1059 | 0.73–0.76 |

| n-C26 | 7.5–10 | 500–1250 | 15–16 | 0–1000 | 15–17 | 941–1028 | 0.80–0.84 |

| n-C28 | 7.5–10 | 750–1500 | 8–9 | 0–1050 | 10–11 | 1167–1312 | 0.78–0.81 |

| n-C30+32 | 12.5 | 750–2250 | 25 | 0–1600 | 26 | 1541–1853 | 0.70–0.74 |

| Comb. n-C24−32 | 7.5 | 500–1500 | 15 | 0–1050 | 15 | 1028–1202 | n-C24: 0.68–0.71 |

| n-C26: 0.78–0.81 | |||||||

| n-C28: 0.78–0.82 | |||||||

| n-C30+32: 0.88–0.93 | |||||||

| Avg. long-chain: 0.79–0.83 |

While each simulated fast- or slow-cycling age distribution had only a single μ and σ value, the ranges reported in the table reflect the range of individual μ and σ values that define the top eight best-fitting age distributions. The last table entry for combined long-chain fatty acids reflects the additional modeling experiment of keeping the fast and slow-cycling endmembers (μ and σ) constant for all n-C24+ fatty acids while allowing the fractional contribution to vary independently for each homologue, hence the fslow values listed for each homologue under Comb. n-C24−32.

Because long-chain fatty acids share sources, continental reservoirs, and transport pathways, and the fast- and slow-cycling average ages calculated for the individual long-chain fatty acids were similar (Table 1), an additional analysis was performed to determine which age structure best represents all of the long-chain fatty acids: a combined long-chain fatty acid age structure. For this analysis, the fast- and slow-cycling endmembers were held constant (i.e., constant μFast, σFast, μSlow, and σSlow) for all long-chain fatty acids while allowing fractional contributions to vary for each homologue. Using this approach, a combined n-C24−32 RMSE was calculated to assess which age structures best approximate the long-chain fatty acid data on the whole. Accordingly, the eight best-fitting fast- and slow-cycling age distributions for the leaf-wax fatty acids have average ages of 15 and 1,028–1,202 calendar years, respectively, and fSlow increases with increasing chain length (Fig. 1). Weighing fSlow according to average fatty acid concentrations gives a leaf-wax fatty acid fSlow range of 0.79 to 0.83. Despite slightly less optimal fits, the top 9–100 best-fitting age distributions for the long-chain fatty acids have similar fast and slow average ages (13–18 years and 941–1,396 years, respectively) and fractional contributions (average long-chain fSlow = 0.75–0.88) (Supplementary Fig. S10, Table S9).

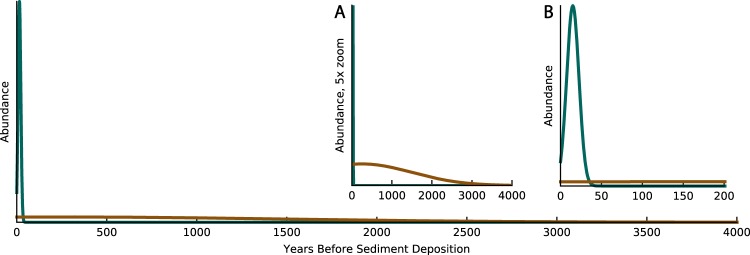

The top eight best-fitting age distributions are set by μFast = 15 years, σFast = 7.5 years, μSlow = 0–1,050 years, and σSlow = 500–1,500 years (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The best-fitting age distributions range more in their μSlow and σSlow than in their slow-cycling average ages (1,028–1,202 years) because of an inverse relationship between μSlow and σSlow for these optimal age distributions. This inverse relationship between μSlow and σSlow means that the slow-cycling age distribution has a broader distribution if it is centered near the sediment deposition age and the distribution narrows as the center of the distribution moves further away from sediment deposition age. We argue that broader distributions centered on or near the sediment deposition age more likely represent soil profiles that accumulate modern biomass while at the same time abundances of older carbon attenuate as degradation proceeds.

Figure 2.

The best-fitting fast- and slow-cycling age distribution for leaf-wax fatty acids where the fast-cycling age distribution (green) and the slow-cycling age distribution (brown) are set by the following parameters: μFast = 15 yr, σFast = 7.5 yr, μSlow = 250 yr, and σSlow = 1,250 yr. The fast- and slow-cycling components represent 17% and 83%, respectively, of the concentration weighted leaf-wax fatty acids for this age distribution. In the model, the y-axis is related to the probability density function, but it can be conceptualized as relative fatty acid abundance that was biosynthesized in a given year and has not yet been degraded. The y-axis is rescaled in subpanel A to better show the slow-cycling distribution, and the x-axis is rescaled in subpanel B to better show the fast-cycling distribution.

Similar fSlow and δ13C values for n-C16 and the long-chain fatty acids suggest that they are physically sourced from the same continental reservoirs. However, faster degradation rates may explain younger slow-cycling component ages for shorter-chain compounds28,29, particularly n-C16. Likewise, different degradation rates also explain variations in fSlow for the long-chain fatty acids when the endmembers are held constant.

Our model assumes that the endmember age distributions and their fractional contributions remain constant over the sampling interval (1946–2003), despite concurrent land-use changes within the G-B catchment. While anthropogenic activity can impact sediment and OC transport, the relatively constant fatty acid δ13C values and homologue distributions suggests that anthropogenic activity has not significantly altered the supply of terrestrial fatty acids to the shelf canyon during the sampling interval. Moreover, the relatively constant bulk properties (TOC, Al/Si, 87Sr/86Sr, and εNd values; Supplemental Table S1) indicate relative depositional stasis over this interval. In contrast, these geochemical parameters fluctuate more significantly over thousands of years in the G-B system15,30, demonstrating that the system is capable of a much larger degree of variability than observed over the time interval captured in the SO188–336KL core. Although not conclusive, the observation that fatty acid and bulk OC Fm values approach pre-bomb levels in the latter part of the record supports the assumption of a stable OC source. Finally, the extensive size of the G-B rivers and Himalayas may buffer the system from anthropogenic effects over our short sampling interval.

We combine our long-chain fatty acid age structure with the bulk OC Fm to refine the previous age structure estimates of bulk OC in the G-B basin3 (see Supplemental Information (SI)). These results suggest that ~10–15% of the bulk OC is decadal (average age 15 years), ~47–60% is labile millennial OC (average age 1,000–1,200 years), ~23–35% is refractory OC (>15,000 years), and ~5% is petrogenic (radiocarbon-dead) (Supplementary Fig. S11). These results compare well with previous estimates of old refractory OC (>15,000 years) representing 20% of the total biospheric carbon exported from the G-B rivers3. Pre-aged soil OC emanating from the G-B basin thus dominates the total OC budget — a feature that has been observed in other world rivers31. Future research is needed to identify which combinations of microbial degradation and erosional processes generate the age structure of organic matter delivered to the Bengal Fan.

According to the fatty acid and bulk OC age distributions resolved in this study, reservoirs that host centennial and millennial carbon, such as soils, floodplains, and wetlands24, dominate the riverine supply of OC to Bengal Fan sediments. Successive periods of storage and remobilization of sediments pre-ages the majority of the leaf-wax fatty acids and OC delivered to the Bengal Fan3. Physical and climatic features such as topography, temperature, precipitation, and catchment area likely determine the endmember ages and fractional contributions, suggesting that fatty acid age structures vary spatially and temporally. While additional investigation is required before extrapolating our age structures to other localities, a significant centennial and millennial fatty acid contribution may explain the old leaf-wax radiocarbon ages observed in a wide range of environments1,2,4,19,32.

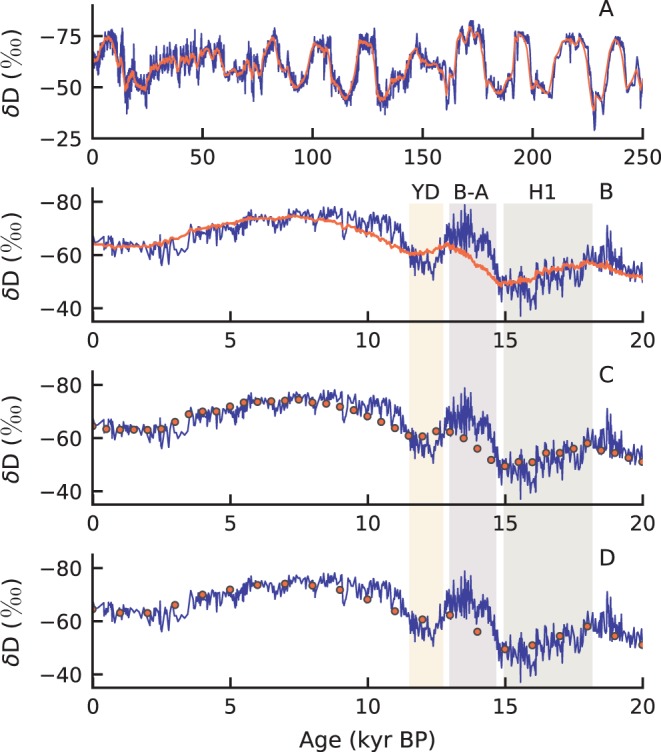

The contribution of large amounts of pre-aged continental OC to sedimentary archives may affect paleoclimate records derived from associated biomarkers. To test the significance of this effect, we simulated a 250 kyr leaf-wax fatty acid δD sedimentary record. Accordingly, the composite δ18O record from Chinese cave deposits33 was interpolated to yearly resolution and then converted to δD using a southeast Asia meteoric water line34. This primary climate record was then filtered through the best-fitting long-chain fatty acid age solution (μFast = 15 yr, σFast = 7.5 yr, μSlow = 250 yr, σSlow = 1,250 yr, and fSlow = 0.8) to generate a synthetic leaf-wax δD sedimentary record. This age structure introduces time lags across geologically rapid events, such as the Younger Dryas and Bølling-Allerød, and prevents the fatty acid record from expressing the full magnitude of the decadal to centennial high-frequency variability (Fig. 3). The time lags and high-frequency damping effects are visible if the fatty acid synthetic record is sampled on centennial or shorter timescales, but millennial or longer sampling time scales mask the incoherence.

Figure 3.

Effect of leaf-wax fatty acid age structure on paleorecords. The synthetic leaf-wax fatty acid δD record (orange) is plotted against a δD record (blue) derived from the composite δ18O data for Chinese cave speleothems33,34, spanning the last 250,000 years (panel A) and the last 20,000 years (panel B). The millennial fatty acid component damps the decadal to centennial high-frequency variability that is present in the speleothem record. The Younger Dryas (YD), Bølling-Allerød (B-A), and Heinrich 1 (H1) events are labeled. The millennial fatty acid component introduces time lags where events such as the B-A occur later in the synthetic fatty acid record than in the speleothem record. The synthetic leaf-wax fatty acid data are sampled every 500 years (panel C) and every 1,000 years (panel D).

The synthetic leaf-wax δD deviates from measured terrestrial biomarker δD records that are available from the Bay of Bengal for several reasons30,35. First, the Chinese caves may not record the same climate and monsoon variability that the G-B floodplain and Indo-Burma region export to the Bengal Fan and Eastern Bengal Slope, respectively. Second, the decadal to centennial high-frequency damping may not be evident in a measured biomarker δD record due to the analytical uncertainty that is associated with the δD measurement, which is on the same order of magnitude as the decadal to centennial high-frequency climate variability in the Chinese cave record36. Finally, the fatty acid age structure likely changes over time as climate and hydrological parameters fluctuate22,32 – a variable that is unaccounted for in our synthetic fatty acid δD. As such, a significant deviation between the synthetic and measured leaf-wax δD records could reflect climate-driven changes in terrestrial OC storage timescales.

The fatty acid age distributions suggest that the turnover timescales of OC stored in the G-B basin and exported to the Bengal Fan are longer than current turnover timescale estimates of total ecosystem OC (14 yr) and soil OC (25 yr)37. This discrepancy implies that a vast majority of the net primary production (NPP) in the G-B basin is respired on annual to decadal timescales, but the less-labile OC that escapes respiration accumulates in soils over centuries to millennia. While this OC may be less labile, functionalized lipids, including leaf-wax fatty acids, can be degraded38. As a result, our data imply that the G-B basin may store large quantities of degradable OC that accumulated over centuries to millennia under current and recent climate conditions. Since precipitation is a key driver of soil turnover at low latitude39, natural variations in the strength of the Indian monsoon likely impact the turnover timescales of this large inventory of degradable OC, suggesting that tropical terrestrial OC dynamics may represent an important global climate feedback over glacial/interglacial timescales. Rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns could destabilize this slow-cycling, yet potentially reactive, soil OC pool, reorganizing the balance among oxidation to the atmosphere, storage in soils, and burial in marine sediments. Our estimates of OC residence times within the G-B watershed may serve as a model to assess how soil, floodplain, and wetland response to climate and land-use change quantitatively affects the global carbon cycle.

Methods

Decarbonated samples were analyzed for bulk 14C at ETH Zurich using the elemental analyzer-accelerator mass spectrometer (EA-AMS) MIcroscale CArbon DAting System (MICADAS)40. Samples were additionally analyzed for TOC and Al/Si elemental ratios, while a subset of samples were analyzed for Sr and Nd isotope composition. The fatty acids were isolated from sediment extracts and methylated to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs), which were purified and quantified. The stable carbon isotopic compositions of the FAMEs were analyzed in triplicate by gas chromatography-isotope ratio mass spectrometry (GC-IRMS). For a subset of samples, six individual saturated, straight-chain FAMEs (n-C16, n-C24, n-C26, n-C28, n-C30, and n-C32) were purified and collected for radiocarbon analysis according to the previously established preparative GC method41. These purified FAMEs were combusted to CO2 gas and analyzed at ETH Zurich using the AMS MICADAS system42. The 14C FAME data were corrected for blank contribution by isotope mass balance. Finally, the 14C and 13C FAME data were corrected for methylation. See SI for additional method details and complete data tables.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Carl Johnson for lab support and fatty acid δ13C analysis, Albert Galy and Christian France-Lanord (CRPG; Nancy, France) for inorganic measurements, and Kyrstin Fornace and Deepak Cherian for discussions. We acknowledge funding support from the Agouron Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship (K.L.F), the US National Science Foundation (Awards: OCE-1333387 and OCE-13333826), the Investment in Science Fund given primarily by WHOI Trustee and Corporation Members, and the Swiss National Science Foundation (Award: 200020_163162). Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author Contributions

K.L.F., C.J.H., and V.G. designed the study. K.L.F., C.J.H., N.H., L.W., H.R.K., and T.I.E. contributed to the analysis. K.L.F. drafted the manuscript with contributions from C.J.H., H.R.K., T.I.E., and V.G.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-30091-8.

References

- 1.Feng X, et al. Differential mobilization of terrestrial carbon pools in Eurasian Arctic river basins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:14168–14173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307031110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kusch S, Rethemeyer J, Schefuß E, Mollenhauer G. Controls on the age of vascular plant biomarkers in Black Sea sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2010;74:7031–7047. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2010.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galy V, Eglinton T. Protracted storage of biospheric carbon in the Ganges–Brahmaputra basin. Nature Geoscience. 2011;4:843–847. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drenzek, N. J. The temporal dynamics of terrestrial organic matter transfer to the oceans: Initial assessment and application Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2007).

- 5.Eglinton G, Hamilton RJ. Leaf Epicuticular Waxes. Science. 1967;156:1322–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.156.3780.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galy, A. & France-Lanord, C. Higher erosion rates in the Himalaya: Geochemical constraints on riverine fluxes. Geology29, 23, doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0023:herith>2.0.co;2 (2001).

- 7.Curray JR, Emmel FJ, Moore DG. The Bengal Fan: morphology, geometry, stratigraphy, history and processes. Marine and Petroleum Geology. 2002;19:1191–1223. doi: 10.1016/S0264-8172(03)00035-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galy V, et al. Efficient organic carbon burial in the Bengal fan sustained by the Himalayan erosional system. Nature. 2007;450:407–410. doi: 10.1038/nature06273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galy, V., Peucker-Ehrenbrink, B. & Eglinton, T. Global carbon export from the terrestrial biosphere controlled by erosion. Nature521, 204–207, 10.1038/nature14400 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Galy, V., Hein, C., France-Lanord, C. & Eglinton, T. In Biogeochemical Dynamics at Major River-Coastal Interfaces: Linkages with Global Change (eds Bianchi, T., Allison, M. & Cai, W.-J.) Ch. 13, 353–372 (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

- 11.Milliman, J. D. & Farnsworth, K. L. River Discharge to the Coastal Ocean. 384 (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- 12.Michels KH, Suckow A, Breitzke M, Kudrass HR, Kottke B. Sediment transport in the shelf canyon “Swatch of No Ground” (Bay of Bengal) Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. 2003;50:1003–1022. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(02)00617-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kudrass H, Michels KH, Wiedicke M, Suckow A. Cyclones and tides as feeders of a submarine canyon off Bangladesh. Geology. 1998;26:715–718. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(1998)026<0715:CATAFO>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierson-Wickmann A-C, Reisberg L, France-Lanord C, Kudrass HR. Os-Sr-Nd results from sediments in the Bay of Bengal: Implications for sediment transport and the marine Os record. Paleoceanography. 2001;16:435–444. doi: 10.1029/2000PA000532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galy V, France-Lanord C, Peucker-Ehrenbrink B, Huyghe P. Sr–Nd–Os evidence for a stable erosion regime in the Himalaya during the past 12Myr. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2010;290:474–480. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2010.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eglinton TI, Eglinton G. Molecular proxies for paleoclimatology. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2008;275:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2008.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galy V, Eglinton T, France-Lanord C, Sylva S. The provenance of vegetation and environmental signatures encoded in vascular plant biomarkers carried by the Ganges–Brahmaputra rivers. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2011;304:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2011.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galy V, France-Lanord C, Lartiges B. Loading and fate of particulate organic carbon from the Himalaya to the Ganga–Brahmaputra delta. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2008;72:1767–1787. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.01.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drenzek NJ, Montluçon DB, Yunker MB, Macdonald RW, Eglinton TI. Constraints on the origin of sedimentary organic carbon in the Beaufort Sea from coupled molecular 13C and 14C measurements. Marine Chemistry. 2007;103:146–162. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2006.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohkouchi N, Eglinton TI, Hayes JM. Radiocarbon dating of individual fatty acids as a tool for refining Antarctic margin sediment chronologies. Radiocarbon. 2003;45:17–24. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200032355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uchida M, et al. Compound-specific radiocarbon ages of fatty acids in marine sediments from the western North Pacific. Radiocarbon. 2001;43:949–956. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200041618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fornace, K. L. Late Quaternary climate variability and terrestrial carbon cycling in tropical South America Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2016).

- 23.Douglas PMJ, et al. Pre-aged plant waxes in tropical lake sediments and their influence on the chronology of molecular paleoclimate proxy records. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 2014;141:346–364. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2014.06.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trumbore S. Radiocarbon and Soil Carbon Dynamics. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 2009;37:47–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.earth.36.031207.124300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reimer PJ, et al. INTCAL13 and MARINE13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0–50,000 years CAL BP. Radiocarbon. 2013;55:1869–1887. doi: 10.2458/azu_js_rc.55.16947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hua Q, Barbetti M, Rakowski AZ. Atmospheric Radiocarbon for the Period 1950–2010. Radiocarbon. 2013;55:2059–2072. doi: 10.2458/azu_js_rc.v55i2.16177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Walt S, Colbert SC, Varoquaux G. The NumPy Array: A Structure for Efficient Numerical Computation. Computing in Science and Engineering. 2011;13:22–30. doi: 10.1109/MCSE.2011.37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haddad R, Martens CS, Farrington JW. Quantifying early diagenesis of fatty acids in a rapidly accumulating coastal marine sediment. Org. Geochem. 1992;19:205–216. doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(92)90037-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canuel EA, Martens CS. Reactivity of recently deposited organic matter: Degradation of lipid compounds near the sediment-water interface. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1996;60:1793–1806. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(96)00045-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hein CJ, et al. Post-glacial climate forcing of surface processes in the Ganges–Brahmaputra river basin and implications for carbon sequestration. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2017;478:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2017.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tao S, Eglinton TI, Montluçon DB, McIntyre C, Zhao M. Pre-aged soil organic carbon as a major component of the Yellow River suspended load: Regional significance and global relevance. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 2015;414:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2015.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schefuß E, et al. Hydrologic control of carbon cycling and aged carbon discharge in the Congo River basin. Nature Geoscience. 2016;9:687–690. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng H, et al. The Asian monsoon over the past 640,000 years and ice age terminations. Nature. 2016;534:640–646. doi: 10.1038/nature18591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Araguás-Araguás L, Froehlich K, Rozanski K. Stable isotope composition of precipitation over southeast Asia. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 1998;103:28721–28742. doi: 10.1029/98JD02582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Contreras-Rosales LA, et al. Evolution of the Indian Summer Monsoon and terrestrial vegetation in the Bengal region during the past 18 ka. Quaternary Science Reviews. 2014;102:133–148. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sessions AL. Isotope-ratio detection for gas chromatography. Journal of Separation Science. 2006;29:1946–1961. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200600002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bloom AA, Exbrayat JF, van der Velde IR, Feng L, Williams M. The decadal state of the terrestrial carbon cycle: Global retrievals of terrestrial carbon allocation, pools, and residence times. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:1285–1290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515160113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyers PA, Eadie BJ. Sources, degradation and recycling of organic matter associated with sinking particles in Lake Michigan. Org. Geochem. 1993;20:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(93)90080-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carvalhais N, et al. Global covariation of carbon turnover times with climate in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature. 2014;514:213–217. doi: 10.1038/nature13731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruff M, et al. On-line radiocarbon measurements of small samples using elemental analyzer and MICADAS gas ion source. Radiocarbon. 2010;52:1645–1656. doi: 10.1017/S003382220005637X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eglinton TI, Aluwihare LI, Bauer JE, Druffel ERM, McNichol AP. Gas Chromatographic Isolation of Individual Compounds from Complex Matrices for Radiocarbon Dating. Anal Chem. 1996;68:904–912. doi: 10.1021/ac9508513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christl M, et al. The ETH Zurich AMS facilities: Performance parameters and reference materials. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms. 2013;294:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.nimb.2012.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.