Abstract

Microduplication of 22q11.2 involves having an extra copy at position q11.2 on chromosome 22. Very few cases have been reported but the real incidence may be higher as the absence of obvious clinical signs makes diagnosis difficult. In the cases that are diagnosed, the phenotype is extremely variable. We describe a case of severe micrognathia, cleft palate, and Pierre-Robin sequence. A prenatal ultrasound showed severe micrognathia and subsequent microarray done on amniocentesis revealed the microduplication of 22q11.2, which was confirmed postnatally. Although micrognathia has often been detected in this microduplication, the constellation of these findings has not been previously described.

Keywords: 22q11.2 microdeletion, 22q11.2 microduplication, micrognathia, cleft palate, Pierre-Robin sequence

Introduction

Microduplication of 22q11.2 involves having an extra copy at position q11.2 on chromosome 22. 1 The duplicated region usually contains 30 to 40 genes with approximately 3 megabases (Mb) of DNA base pairs. 1 The phenotype of 22q11.2 microduplication is highly variable but usually mild. Since its first description 15 years ago, there are less than 100 cases reported but the estimated incidence is higher, especially in individuals with developmental problems. 1 2 Although micrognathia has been shown to be associated with this microduplication, we describe a case of severe micrognathia, cleft palate, and Pierre–Robin sequence, which has not been previously described.

Clinical Case Report

A male infant was born to a 38-year-old Caucasian multigravida, who had normal prenatal laboratory tests. The mother had no significant medical history and no history of recurrent infections. On history, she had no potential teratogenic exposures. Family history was negative for cleft palate, micrognathia, birth defects, or developmental disabilities and his three half siblings were healthy. The mother had normal gestational diabetes screening done at 28 weeks gestation and her physical examination did not reveal any anomalies. A prenatal ultrasound showed fetal micrognathia and subsequently, a chromosome microarray done following amniocentesis revealed interstitial microduplication of 22q11.21. Parental testing revealed that the father of the baby carried a similar duplication and he had a history of undergoing speech therapy at school age. At delivery at 36 weeks gestation, the infant had a birth weight of 2,945 g (50th centile), length of 48 cm (50th centile), and head circumference of 33 cm (50th centile). He did not require any resuscitation but physical examination revealed severe micrognathia, Pierre-Robin sequence with glossoptosis, and a posterior cleft palate. No other abnormalities were detected and the patient had a normal echocardiogram. After birth, the infant's microarray confirmed the prenatal diagnosis. As the patient required prone positioning for maintaining his airway, he underwent mandibular distraction ( Fig. 1 ). Subsequently, he had a gastrostomy tube placed due to feeding difficulty. He was discharged home with a weight of 3,905 g. He was seen at follow-up routinely and it was noted that he had palatal surgery at 11 months and his last follow-up at 18 months of age showed that his weight was at 25th centile and head circumference at the 50th centile. A Bailey III test performed at that time showed a cognitive score at the 50th centile (age equivalent 16 months), receptive at 13 months, expressive at the 42nd centile (17 months age equivalent) fine motor at 18 months age equivalent, and gross motor at the 79th centile.

Fig. 1.

Patient with severe micrognathia after correction by mandibular distraction.

Detailed Genetic Findings

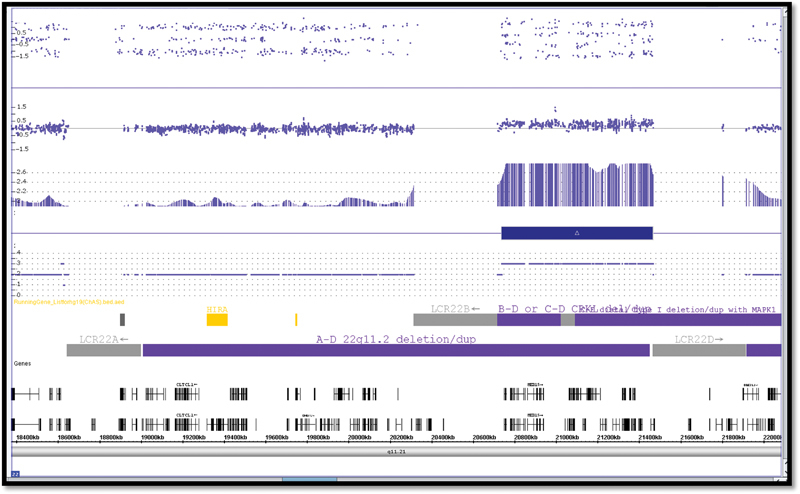

The karyotype was 46, XY ( Fig. 2 ). A 728 Kb interstitial duplication of 22 q11.21- arr (hg 19) (20,737, 912–21, 465, 659) x3 by whole genome single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray (Reveal) chromosome microarray analysis using the Affymetrix Cytoscan HD platform (Integrated Genetics, Sante Fe, New Mexico, United States). It included 11 genes (ZNF74 to SLC7A4) and spans low copy repeats (LCR) B-D and was localized to the distal end of 2.5 Mb DiGeorge/velocardiofacial (DG/VCF) region ( Fig. 3 ). Paternal targeted quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis using a two tailed approach with forward and reverse primers to amplify the localized CRKL gene, was performed revealing a similar micro-duplication of 22q11.2.

Fig. 2.

Karyotype of patient showing 46 XY.

Fig. 3.

Single nucleotide polymorphism microarray.

Discussion

Early reports describing 22q11.2 microduplication occurred in 1999 and in 2003. 3 4 Even though less than 100 cases have been reported, the real incidence may be higher due to the absence of obvious clinical or dysmorphic signs. 1 2 This microduplication is not detectable by routine G-banded karyotyping and only identified by chromosomal microarray testing such as array comparative genomic hybridization or multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification. Other genomic tests such as SNP array, interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization, or quantitative PCR may confirm the diagnosis. The sequence analysis of the coding and flanking intronic regions of the genomic DNA is used to confirm the duplication and determine the size of the duplication. 5

The 11.2 region on the long arm (q) of chromosome 22 contains a region with 8 LCR designated LCR A-H that can mediate nonallelic homologous recombination. This LCR region 22A-22H is susceptible to both microdeletions and microduplications due to misalignment, resulting in rearrangements. 2 5 6 Of these, the most commonly duplicated region extends from LCR22-A to 22-D and encompasses 40 genes including the TBX1 gene. The TBX1 gene deletion is responsible for the DiGeorge/velocardiofacial syndrome (DG/VCFS), and hence this duplication is the reciprocal of the common DG/VCFS deletion. Duplications ranging from 1.5 Mb to 6 Mb have been reported. 2 5 6

The clinical findings are often subtle and the phenotype is usually mild and range from apparently normal-to-mild intellectual or learning disability, delayed psychomotor development, growth retardation, and hypotonia. 7 8 Some have clinical similarities to 22q11.2 microdeletion syndromes including heart defects, urogenital abnormalities, velopharyngeal insufficiency with or without cleft palate and, hence, this duplication is most often detected when patients who were initially suspected to have DG/VCFS were tested. Microarray testing of an apparently normal parent of an affected child results in a 22q11.2 duplication suggesting that many individuals can harbor this duplication with no phenotypic effect and inheritance is now estimated at 70%. 6 7 8 The etiology of the phenotypic variability is not known, but proposed explanations include non-penetrance, epigenetic factors, modifier genes, and environmental factors. 8

The 22q11.2 deletions occur at a frequency of 1 in 4,000 to 6,000 live births, whereas 22q11.2 duplication is rarely diagnosed, confounding the theory that microdeletions and microduplications occur at the same frequency.

This duplication has been shown to be associated with minor ear anomalies, hypertelorism, mild micrognathia, congenital heart defects, velopharyngeal insufficiency and cleft lip or palate, hearing loss, and seizures. 1 There are some reports of esophageal atresia and VACTERL association. 9 10 11 The other anomalies are quite varied and include ocular anomalies, microcephaly, cleft lip, thyroid hemiagenesis, and subtle dysmorphic facial features. 8 12 13 14 15

In addition, an increasing number of recent studies have shown a higher incidence of autism spectrum and psychiatric disorders in those with this microduplication but, surprisingly, it has also been shown to provide some protection against schizophrenia. 16 17 18 19 20 21 There are reports of variable cognitive deficits, which are generally mild. 1 2 6 8 9 22

This case illustrates the considerable challenges in interpreting copy number variations. A review of the phenotype of microduplications involving similar LCRs did not establish any clear genotype correlation. 6 The pathogenicity cannot be predicted based on the Mb size of the duplication or by the phenotype in the same family and as many parental carriers have a normal phenotype. 6 8 14 23 24 25

If a microduplication is detected, a search for other mutations should be done, as it is likely that other genes may play a role in the phenotypic expression. The “second hit” theory suggested recently for concomitant chromosomal imbalances, such as microdeletions, additional duplications, missense mutations, and reciprocal translocation, may add to the severity of the cognitive disorders. 6 8 9

In our patient, a proximal duplication was detected but there were no other concomitant genotypic anomalies. It is possible that the phenotypic anomalies are totally unrelated to the microduplication, but this does bear some similarity to DG/VCFS spectrum.

Conclusion

Even though there are some phenotypic trends, there is great variability among cases of 22q11.2 microduplication. Thus, if this microduplication is detected in the fetus prenatally, counseling of prospective parents related to prognosis is difficult. Our case report highlights features that previously have not been reported in the 22q11.2 microduplication syndrome. In cases of congenital anomalies without a clear genetic diagnosis, there is an increasing use of whole genome sequencing, exome analysis, or microarray, as the standard screening, and many more of these duplications are likely to be detected and concomitant anomalies are also picked up. 6 8 9 26 However, this enigmatic genetic disorder with its diverse phenotypic presentations and variable expressivity still confounds many clinicians. It is, therefore, extremely important that the entire range and diverse presentations are captured and these reports will eventually delineate the full spectrum of the phenotype, so as to aid prospective parents in counseling and help in providing adequate prenatal care and support.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Conflict of Interest None.

Additional Note

Full consent was obtained from the patient's parents for the case report. Research and ethics board approval has been obtained.

References

- 1.Firth' H V.22q11.2 Duplication. 2009 Feb 17 [updated 2013 Nov 21] Seattle (WA)University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2017.. Available at:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK3823/PubMed PMID: 20301749. Accessed January 2, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Campenhout S, Devriendt K, Breckpot J et al. Microduplication 22q11.2: a description of the clinical, developmental and behavioral characteristics during childhood. Genet Couns. 2012;23(02):135–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edelmann L, Pandita R K, Spiteri E et al. A common molecular basis for rearrangement disorders on chromosome 22q11. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(07):1157–1167. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.7.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ensenauer R E, Adeyinka A, Flynn H C et al. Microduplication 22q11.2, an emerging syndrome: clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular analysis of thirteen patients. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73(05):1027–1040. doi: 10.1086/378818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stachon A C, Baskin B, Smith A C et al. Molecular diagnosis of 22q11.2 deletion and duplication by multiplex ligation dependent probe amplification. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A(24):2924–2930. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinchefsky E, Laneuville L, Srour M. Distal 22q11.2 microduplication: case report and review of the literature. Child Neurol Open. 2017;4:2.329048E6–X17737651. doi: 10.1177/2329048X17737651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ou Z, Berg J S, Yonath H et al. Microduplications of 22q11.2 are frequently inherited and are associated with variable phenotypes. Genet Med. 2008;10(04):267–277. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31816b64c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wentzel C, Fernström M, Ohrner Y, Annerén G, Thuresson A C. Clinical variability of the 22q11.2 duplication syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2008;51(06):501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nguyen L T, Fleishman R, Flynn E et al. 22q11.2 microduplication syndrome with associated esophageal atresia/tracheo-esophageal fistula and vascular ring. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(03):351–356. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puvabanditsin S, Garrow E, February M, Yen E, Mehta R. Esophageal atresia with recurrent tracheoesophageal fistulas and microduplication 22q11.23. Genet Couns. 2015;26(03):313–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schramm C, Draaken M, Bartels E et al. De novo microduplication at 22q11.21 in a patient with VACTERL association. Eur J Med Genet. 2011;54(01):9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordovez J A, Capasso J, Lingao M D et al. Ocular manifestations of 22q11.2 microduplication. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(01):392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim H J, Jo H S, Yoo E G et al. 22q11.2 microduplication with thyroid hemiagenesis. Horm Res Paediatr. 2013;79(04):243–249. doi: 10.1159/000346411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wincent J, Bruno D L, van Bon B W et al. Sixteen new cases contributing to the characterization of patients with distal 22q11.2 microduplications. Mol Syndromol. 2010;1(05):246–254. doi: 10.1159/000327982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sedghi M, Abdali H, Memarzadeh M et al. Identification of proximal and distal 22q11.2 microduplications among patients with cleft lip and/or palate: a novel inherited atypical 0.6 Mb duplication. Genet Res Int. 2015;2015(15):398063. doi: 10.1155/2015/398063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenger T L, Miller J S, DePolo L M et al. 22q11.2 duplication syndrome: elevated rate of autism spectrum disorder and need for medical screening. Mol Autism. 2016;7:27. doi: 10.1186/s13229-016-0090-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clements C C, Wenger T L, Zoltowski A R et al. Critical region within 22q11.2 linked to higher rate of autism spectrum disorder. Mol Autism. 2017;8:58. doi: 10.1186/s13229-017-0171-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoeffding L K, Trabjerg B B, Olsen L et al. Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals with the 22q11.2 deletion or duplication: a Danish nationwide, register-based study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(03):282–290. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Amelsvoort T, Denayer A, Boermans J, Swillen A. Psychotic disorder associated with 22q11.2 duplication syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 2016;236:206–207. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rees E, Kirov G, Sanders A et al. Evidence that duplications of 22q11.2 protect against schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(01):37–40. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brunet A, Armengol L, Pelaez T et al. Failure to detect the 22q11.2 duplication syndrome rearrangement among patients with schizophrenia. Behav Brain Funct. 2008;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribeiro-Bicudo L A, de Campos Legnaro C, Gamba B F, Candido Sandri R M, Richieri-Costa A. Cognitive deficit, learning difficulties, severe behavioral abnormalities and healed cleft lip in a patient with a 1.2-mb distal microduplication at 22q11.2. Mol Syndromol. 2013;4(06):292–296. doi: 10.1159/000354095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weisfeld-Adams J D, Edelmann L, Gadi I K, Mehta L. Phenotypic heterogeneity in a family with a small atypical microduplication of chromosome 22q11.2 involving TBX1. Eur J Med Genet. 2012;55(12):732–736. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de La Rochebrochard C, Joly-Hélas G, Goldenberg A et al. The intrafamilial variability of the 22q11.2 microduplication encompasses a spectrum from minor cognitive deficits to severe congenital anomalies. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140(14):1608–1613. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yobb T M, Somerville M J, Willatt L et al. Microduplication and triplication of 22q11.2: a highly variable syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76(05):865–876. doi: 10.1086/429841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wapner R J, Martin C L, Levy B et al. Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(23):2175–2184. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]