Abstract

Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the occurrence of multiple, symmetrical lesions in the oral cavity. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has been suggested as an etiological factor in OLP. The purpose of this review was to summarize the current literature regarding the treatment of OLP in patients with HCV infection. An electronic search of the PubMed database was conducted until January 2018, using the following keywords: OLP, HCV, corticosteroids, retinoids, immunomodulatory agents, surgical interventions, photochemotherapy, laser therapy, interferon, ribavirin, and direct-acting antivirals. We selected the articles focusing on the clinical features and treatment management of OLP in patients with/without HCV infection. Topical corticosteroids are considered the first-line treatment in OLP. Calcineurin inhibitors or retinoids can be beneficial for recalcitrant OLP lesions. Systemic therapy should be used in the case of extensive and refractory lesions that involve extraoral sites. Surgical intervention is recommended for isolated lesions. In patients with HCV, monotherapy with interferon (IFN)-α may either improve, aggravate or trigger OLP lesions, while combined IFN-α and ribavirin therapy does not significantly influence the progression of lesions. Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy appears to be a promising approach in patients with HCV-related OLP, as it can improve symptoms of both liver disease and OLP, with fewer side effects. Nevertheless, for clinical utility of DAAs in OLP patients, further studies with larger sample sizes, adequate treatment duration, and long term follow-up are required.

Keywords: Oral lichen planus, OLP, hepatitis C virus infection, HCV, management of oral pathology, direct acting antivirals, DAA

INTRODUCTION

Lichen planus (LP) is a chronic, inflammatory, mucocutaneous disease that affects 1–2% of the general population. LP can develop in one or more mucosal and nonmucosal (cutaneous) sites in the body. For instance, it may occur in the mucosa of the oral cavity alone, the skin alone, the oral cavity and skin simultaneously, or in other extraoral sites, such as the scalp, esophagus, nails and genital areas [1,2].

The prevalence of oral LP (OLP) varies between 0.2–2.3% in the literature; moreover, it represents 0.6% of all oral diseases that dentists frequently encounter. OLP mostly occurs in adults aged 30–70 years and women are more commonly affected [3]. A typical manifestation of OLP are multiple, symmetrical lesions that appear in reticular, plaque-like, papular, atrophic (erythematous), erosive or vesicullo-bullous form. Erythematous lesions are often associated with reticular lesions, while erosive lesions are accompanied by both reticular and erythematous lesions in most cases. Generally, the lesions are predominant within the lips, in the buccal and lingual mucosa, and on the dorsal tongue [2,4-6]. Reticular is the most frequent form of OLP, characterized by numerous interlacing white keratotic lines termed Wickham’s striae [6]. Papular type consist of white papules with striae. Erosive form presents as a mixture of erythematous and ulcerative areas, while in atrophic form erythematous areas are combined with white striae [3,6]. Bullous form is a rare type of OLP and consists of bubbles (bullae) that rupture almost immediately after they appear [3,6]. Erosive, atrophic, and ulcerative OLP lesions are often associated with pain and burning sensation and can cause problems with eating, speaking, and swallowing. In these cases, a differential diagnosis with burning mouth syndrome (BMS) should be made [7-9]. Characteristic symptoms of BMS include burning sensation and pain in the tongue and/or oral mucosa. These symptoms may improve after ingestion of food and liquid, but are, nevertheless, continuous over a period of 4–6 months [9]. Additional symptoms related to BMS are xerostomia, dysgeusia, metallic taste, mood changes, and alterations in chemosensory perception [9]. The main difference between OLP and BMS is that pathological changes in the oral mucosa are not observed in patients with BMS [9].

Although the exact pathogenesis of OLP remains unclear, immunological mechanisms are likely to play an important role [4,5]. OLP is considered to be a T cell-mediated autoimmune disease in which cluster of differentiation 8 (CD8)+ T cells trigger apoptosis of basal epithelial cells. Upon antigen expression by keratinocytes, CD8+ cells that have migrated into the epithelium are activated either by antigen binding to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I on keratinocyte or via activated CD4+ lymphocytes. For example, a study demonstrated that the cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T-cell clones, isolated from lesional T-cell lines, against autologous lesional keratinocytes was blocked partially by anti-MHC class I monoclonal antibodies [10,11]. The precise cause of chronic OLP is not fully elucidated, however the role of a T-cell-produced chemokine RANTES (Regulated on Activation, Normal T-cell Expressed and Secreted) was suggested. Evidently, RANTES recruits lymphocytes and mast cells in OLP. The chemokine triggers mast cell degranulation and their release of pro-inflammatory mediators such as chymase and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) which in turn upregulate the secretion of RANTES by OLP lesional T cells, setting a vicious cycle [12-14].

Since the discovery of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in 1989, infection with HCV has become a major health problem worldwide [15]. Based on the estimates of the World Health Organization (WHO) from 2015 71 million people worldwide are infected with HCV [15]. About 60–70% of infected individuals fail to clear the virus within 6 months and develop chronic disease. In most cases, chronic HCV is slowly progressive and with no obvious signs of liver disease. However, in 20–30% of chronically infected individuals, HCV leads to liver cirrhosis in the first 20 years of infection, and is associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma [16]. HCV has been suggested as an etiological factor in OLP [12].

The purpose of this review was to summarize the current literature regarding the treatment of OLP in patients with HCV infection. An electronic search of the PubMed database was conducted until January 2018, using the following keywords: OLP, HCV, corticosteroids, retinoids, immunomodulatory agents, surgical interventions, photochemotherapy, laser therapy, interferon, ribavirin, and direct-acting antivirals. We selected the articles focusing on the clinical features and treatment management of OLP in patients with/without HCV infection.

ORAL LICHEN PLANUS AND HEPATITIS C VIRUS

The prevalence of OLP in chronic HCV patients varies between different geographical areas and is reported to be 1.5% in North America and Northern Europe; 1.5–3.5% in South Asia, Central and Latin America, Australia, Western and Eastern Europe; >3.5% in the Middle East, North Africa, Central and East Asia; and 35% in Egypt, Japan and Southern Europe [4,17,18]. HCV replication was demonstrated in epithelial LP lesions from buccal mucosa by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or in situ hybridization, and the presence of HCV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes was shown in the sub-epithelial band. Both findings suggest that HCV-specific T lymphocytes may play a role in OLP pathogenesis, where the characteristic band-like lymphocytic infiltrates are directed toward HCV-infected cells. However, despite these findings, the pathogenic link between HCV and OLP is still not completely understood and requires further investigation [12,19].

Carrozzo et al. [20] demonstrated a higher frequency of human leukocyte antigen-antigen D related 6 (HLA-DR6) allele in HCV+ OLP compared to HCV- OLP patients, suggesting that MHC class II alleles could affect the development of OLP in patients with HCV infection [20]. Furthermore, HCV infection has been more frequently associated with erosive than non-erosive OLP type and treatment outcomes are often worse in patients with HCV-related OLP compared to patients suffering from the idiopathic disease. Generally, the progression/worsening of OLP lesions has been linked to the degree of liver decompensation in chronic HCV patients, with periods of exacerbation and relapse of lesions during the follow-up/treatment. On the other hand, no correlation was found between the severity of OLP and HCV viral load or liver disease parameters [21,22].

THERAPEUTIC MANAGEMENT OF ORAL LICHEN PLANUS

The main goal in the management of OLP is to establish an early treatment based on a precise diagnosis, for which accurate understanding of OLP pathogenesis is essential [12]. Several factors should be taken into account when considering a therapy and its cost-effectiveness, including patient medical and dental history, drug interactions, treatment compliance and psychological factors [23].

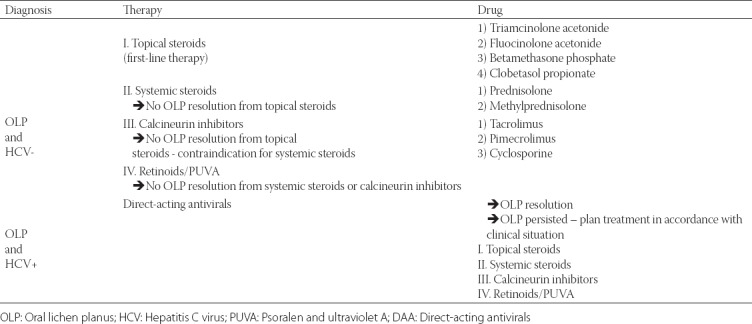

Topical corticosteroids are considered to be the first-line treatment for OLP [19]. These drugs modulate inflammation and immune response by reducing lymphocyte exudates and stabilizing lysosomal membrane [24]. Based on the severity of OLP lesions, topical corticosteroids such as mid-potent triamcinolone acetonide, high-potent fluocinonide or fluocinolone acetonide (fluorinated steroids), betamethasone phosphate, or superpotent halogenated clobetasol propionate may be used [12]. The main disadvantage of topical corticosteroids is their low adherence to the mucosa for a longer period of time. It is recommended to apply clobetasol mixed with adhesive pastes, as they contain inactive components, e.g. vehicle, for topical application. Erosive lesions located on the gingival margin and hard palate can be treated with adherent paste in a custom tray, which allows for accurate control over the contact time and ensures that the entire surface of lesion is exposed to the drug [25]. Most studies indicated that topical corticosteroids are safe when applied to the mucosa for a short period of time, up to 6 months [26-28]. However, long-term use of corticosteroids, especially as a mouthwash, may lead to adrenal suppression in OLP patients [29], and frequent follow-up controls are recommended. Systemic corticosteroids might be more beneficial in those cases in which topical agents are ineffective, for example in recalcitrant, erosive and erythematous OLP. Among systemic drugs, prednisolone is often prescribed, but the drug should be applied at the lowest dose (40–80 mg) and for the shortest duration of time (5–7 days) [30]. When both topical and systemic corticosteroids are not effective immunomodulatory agents, such as calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine, tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) or retinoids, may be helpful [12,19]

Cyclosporine has been used as a mouthwash and in adhesive bases, however, it is not always effective in clinical improvement of OLP. The drug is not generally recommended due to its very low systemic absorption and high price of the solution, and it should be used only in recalcitrant OLP. Moreover, it has been reported that gingival hyperplasia reduces after withdrawal of cyclosporine therapy [12,19,30]. Tacrolimus is a more potent calcineurin inhibitor which can be safely and effectively used in the treatment of recalcitrant and erosive OLP. It has a better absorption and greater capacity to penetrate the oral mucosa compared to cyclosporine. However, a common side effect of tacrolimus is burning sensation [31-37]. In addition, relapse of OLP after the cessation of tacrolimus therapy has been reported [30,31]. A new generation of calcineurin inhibitors is pimecrolimus, which has a lower systemic immunosuppressive potential compared to cyclosporine or tacrolimus. Pimecrolimus topical cream has been successfully used for the treatment of erosive OLP lesions and seems to have a similar effect as triamcinolone acetonide [12,38,39].

Topical retinoids such as tretinoin, isotretinoin or fenretinide, have been reported to cause temporary reversal of white striae in OLP [12]. However, topical retinoids are generally less effective compared with topical corticosteroids [19] because they are associated with side effects such as cheilitis, and high serum levels of triglycerides and liver enzymes [40,41].

Other systemic, immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory therapies have been used for treating OLP, but comprehensive evaluation of their efficacy is lacking [12,19]. Most recently, the use of biologic agents has been suggested, however, due to the low cost-to-benefit ratio their application in OLP is likely to be limited only to severe cases and patients who do not respond to traditional therapies [19].

Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept), a well-tolerated immunosuppressive drug, showed to be effective long term in severe cases of OLP [42]. A preliminary report indicated that a low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparin), when administered subcutaneously, is a simple and effective treatment for LP without causing side effects [43]. Cheng et al. in their case report showed that the treatment with efalizumab, a recombinant humanized monoclonal immunoglobulin G (Ig)G1 antibody, led to the improvement of oral erosions present on buccal mucosa and tongue [44].

Surgical excision has been recommended in OLP patients with isolated plaques and non-healing erosions [45]. Free gingival grafts have been used in localized erosive and symptomatic OLP, showing a complete eradication of disease after 3.5 years. On the other hand, periodontal surgery was shown to induce OLP [46-48]. Cryosurgery has been indicated in erosive and drug-resistant OLP, but lesions may develop during wound healing and in scars [49].

Several studies investigated desquamative gingivitis in OLP patients, which is a condition characterized by epithelial desquamation, erythema, and erosive lesions [5,8,50,51]. Gingival lesions are persistent and painful in OLP patients and, due to the limited efficiency of teeth brushing, plaque accumulation is higher leading to increased risk of long-term periodontal diseases [50]. For favorable results, periodontal therapy consisting of plaque control, oral hygiene program, scaling and root planning, and decay treatment should be applied in a combination with topical corticosteroids [5,51].

Psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy has been successfully used in severe and refractory cases of erosive OLP [52]. However, a systematic review on the efficacy of photodynamic therapy (PDT) in the management of symptomatic OLP showed inconsistent results [53]. For example, two studies reported similar efficacy of PDT and corticosteroids [54,55], while two other studies showed that PDT was inferior to corticosteroids [56,57]. A randomized clinical trial indicated a better efficacy of PDT therapy compared to corticosteroids [58]. Generally, PDT treatment was able to reduce pain and burning sensation and to decrease the size of the lesions in symptomatic OLP patients [53].

Several studies reported the effect of laser therapy on erosive OLP, including the use of 980-nm diode laser [59], carbon dioxide laser evaporation [60], biostimulation with a pulsed diode laser using 904-nm pulsed infrared rays [61] and low-dose excimer 308-nm laser with ultraviolet (UV) B rays [62]. Although promising results were reported by some studies, the effectiveness of laser therapy in OLP is yet to be proven [12].

Therapeutic management of oral lichen planus in patients with HCV

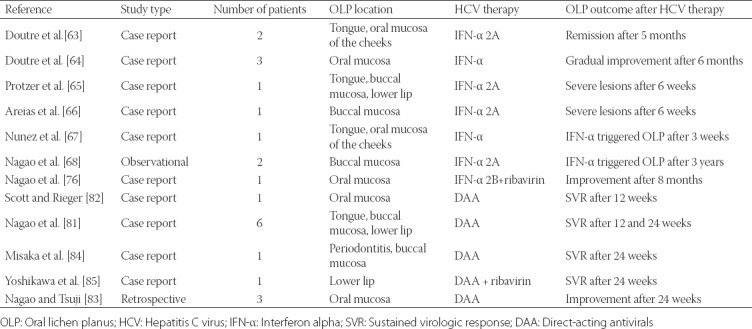

The main publications investigating the efficacy of standard HCV therapies in patients with HCV-related OLP are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

List of publications on the efficacy of standard HCV therapies in OLP patients with HCV

Therapeutic options [12] for OLP patients with and without HCV are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

A monotherapy with interferon alpha (IFN-α) or combined therapy with IFN-α and ribavirin are standard treatments for chronic HCV infection. Different studies reported variable effects of IFN-α therapies on HCV-related OLP, i.e.., IFN-α either improved [63,64], aggravated [65,66], or triggered OLP lesions [67-69]. In Taiwanese patients with HCV, IFN-α and ribavirin combination therapy was associated with an increase in a sustained virologic response (SVR) rate of up to 60%. Generally, the long-term benefits of SVR are a lower risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as improved patient quality of life [70-72]. In chronic HCV patients with SVR to IFN-α and ribavirin therapy, OLP remained persistent in some cases. Moreover, OLP lesions neither disappeared nor improved in patients with negative HCV RNA results following therapy, suggesting that HCV was likely not the main causative agent of OLP. The authors suggested that host factors could play a major role in the pathogenesis of HCV-related OLP [73].

In addition to clinical improvement, IFN-α therapies can cause significant side effects in HCV patients, including fatigue, myalgia, depression, neutropenia, hemolytic anemia, neuropsychiatric symptoms and significant oral dysfunction (dental pulpitis, gingivitis, periodontitis, tooth decay, stomatitis, cheilitis, dry mouth or OLP), indicating the need for individual treatment strategies [74-76]. Nevertheless, in the last decades, clinical support for chronic HCV has advanced due to an enhanced understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease and the improvements in therapy and prevention [77].

Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy achieves SVR rates over 90% and is currently recommended for patients with chronic HCV, based on the degree of liver fibrosis, HCV genotype, resistance variants, previous treatment failure and comorbidities [77,78]. The advantages of DAA over IFN-α and ribavirin therapy are an increased response rate and reduced length of therapy, i.e. from 12 to 6 months. However, side effects such as anemia, leukoplakia, rash, skin reactions, drug interactions, as well as complicated treatment schedules and high cost of medication, are downsides od DAA therapy [79,80].

Nagao et al. [81] investigated the effects of 24-week DAA therapy in 7 patients with HCV-related OLP, among which 3 had erosive type of OLP (including 1 patient who also had cutaneous LP), 3 had reticular, and 1 patient had combined erosive + reticular type. Also, 3/7 patients had previously been treated with topical corticosteroids. OLP symptoms alleviated in all patients after DAA therapy. Complete resolution of OLP was achieved in 4 and partial improvement in 3 patients after SVR for 24 weeks [81]. On the contrary, Scott et al. [82] reported a case of a patient with a 30-year history of OLP, in which a DAA therapy led to the worsening of OLP and development of new cutaneous and genital LP upon achieving SVR. Nagao and Tsuji [83] emphasized the important role of dentists in the discovery of HCV infection in untreated individuals with oral mucosal diseases. In their study, as a result of a dentist request for a detailed evaluation of liver disease, HCV infection could be diagnosed in some patients with OLP, and after a recommended treatment in another clinic SVR was achieved in previously untreated patients with HCV [83].

CONCLUSION

OLP is an inflammatory disease of the oral cavity, commonly encountered by dental practitioners. For proper and timely treatment, early diagnosis is essential. This, however, largely depends on the understanding of etiological and pathophysiological factors involved in OLP. For patients with HCV-related OLP DAA therapy appears to be promising as it can improve symptoms of both liver disease and OLP. Nevertheless, the current research on the effects of DAA treatment on OLP in patients with HCV is limited. Further studies including a larger sample size, adequate treatment duration, and long term follow-up should clarify the underlying mechanisms of DAA drugs in HCV-related OLP.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.De Rossi SS, Ciarrocca K. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid mucositis. Dent Clin North Am. 2014;58(2):299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2014.01.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucchese A, Dolci A, Minervini G, Salerno C, DI Stasio D, Minervini G, et al. Vulvovaginal gingival lichen planus: Report of two cases and review of literature. Oral Implantol (Rome) 2016;9(2):54–60. doi: 10.11138/orl/2016.9.2.054. https://doi.org/10.11138/orl/2016.9.2.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scully C, Carozzo M. Oral mucosa disease: Lichen planus. Br J Oral Maxilofac Surg. 2008;46(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.07.199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.07.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcovich S, Garcovich M, Capizzi R, Gasbarrini A, Zocco MA. Cutaneous manifestations of hepatitis C in the era of new antiviral agents. World J Hepatol. 2015;7(27):2740–8. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i27.2740. https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v7.i27.2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salgado DS, Jeremiah F, Cappella MV, Onofre MA, Massucato EMS, Orrico SRP. Plaque control improves the painful symptoms of oral lichen planus gingival lesions. A short-term study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2013;42(10):728–32. doi: 10.1111/jop.12093. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gheorghe C, Mihai L, Parlatescu I, Tovaru S. Association of oral lichen planus with chronic C hepatitis. Review of the data in literature. Maedica (Buchar) 2014;9(1):98–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leao JC, Ingafou M, Khan A, Scully C, Porter S. Desquamative gingivitis: Retrospective analysis of disease associations of a large cohort. Oral Diseases. 2008;14(6):556–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2007.01420.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-0825.2007.01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lo Russo L, Guiglia R, Pizzo G, Fierro G, Ciavarella D, Lo Muzio L, et al. Effect of desquamative gingivitis on periodontal status: A pilot study. Oral Dis. 2010;16(1):102–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01617.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salerno C, Di Stasio D, Petruzzi M, Lauritano D, Gentile E, Guida A, et al. An overview of burning mouth syndrome. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2016;8:213–8. doi: 10.2741/E762. https://doi.org/10.2741/e762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jungell P, Konttinen YT, Nortamo P, Malmström M. Immunoelectron microscopic study of distribution of T cell subsets in oral lichen planus. Scand J Dent Res. 1989;97(4):361–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1989.tb01624.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0722.1989.tb01624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugerman PB, Satterwhite K, Bigby M. Autocytotoxic T-cell clones in lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(3):449–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03355.x. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavanya N, Jayanthi P, Rao UK, Ranganathan K. Oral lichen planus: An update on pathogenesis and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15(2):127–32. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.84474. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-029X.84474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao ZZ, Sugerman PB, Zhou XJ, Walsh LJ, Savage NW. Mast cell degranulation and the role of T cell RANTES in oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 2001;7(4):246–51. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1601-0825.2001.70408.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roopashree MR, Gondhalekar RV, Shashikanth MC, George J, Thippeswamy SH, Shukla A. Pathogenesis of oral lichen planus - A review. J Oral Pathol Med. 39(10):729–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00946.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO. Global hepatitis report. World Health Organization. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Bisceglie AM. Hepatitis C. Lancet. 1998;351(9099):351–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07361-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petti S, Rabiei M, De Luca M, Scully C. The magnitude of the association between hepatitis C virus infection and oral lichen planus: Meta-analysis and case control study. Odontology. 2011;99(2):168–78. doi: 10.1007/s10266-011-0008-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-011-0008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: New estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1333–42. doi: 10.1002/hep.26141. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carrozo M. Thorpe. Oral lichen planus: A review. Minerva Stomatol. 2009;58(10):519–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrozzo M, Francia Di Celle P, Gandolfo S, Carbone M, Conrotto D, Fasano ME, et al. Increased frequency of HLA-DR6 allele in Italian patients with hepatitis C virus-associated oral lichen planus. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144(4):803–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04136.x. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Kabir M, Scully C, Porter S, Porter K, Macnamara E. Liver function in UK patients with oral lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18(1):12–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1993.tb00957.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.1993.tb00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanei R, Watanabe K, Nishiyama S. Clinical and histopathologic analysis of the relationship between lichen planus and chronic hepatitis C. J Dermatol. 1995;22(5):316–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1995.tb03395.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.1995.tb03395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrozzo M, Gandolfo S. The management of oral lichen planus. Oral Dis. 1999;5(3):196–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1999.tb00301.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-0825.1999.tb00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vincent SD, Fotos PG, Baker KA, Williams TP. Oral lichen planus: The clinical, historical, and therapeutic features of 100 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70(2):165–71. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90112-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(90)90112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez-Moles MA, Ruiz-Avila I, Rodriguez-Archilla A, Morales-Garcia P, Mesa-Aguado F, Bascones-Martinez A, et al. Treatment of severe erosive gingival lesions by topical application of clobetasol propionate in custom trays. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95(6):688–92. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.139. https://doi.org/0.1067/moe.2003.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehner T, Lyne C. Adrenal function during topical oral corticosteroid treatment. Br Med J. 1969;4(5676):138–41. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5676.138. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5676.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plemons JM, Rees TD, Zachariah NY. Absorption of a topical steroid and evaluation of adrenal suppression in patients with erosive lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69(6):688–93. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90349-w. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(90)90349-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carbone M, Goss E, Carrozzo M, Castellano S, Conrotto D, Broccoletti R, et al. Systemic and topical corticosteroid treatment of oral lichen planus: A comparative study with long-term follow-up. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32(6):323–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00173.x. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez-Moles MA, Scully C. Vesiculo-erosive oral mucosal disease. Management with topical corticosteroids: (2) Protocols, monitoring of effects and adverse reactions, and the future. J Dent Res. 2005;84(4):302–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400402. https://doi.org/10.1177/154405910508400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisen D, Carrozzo M, Bagan Sebastian JV, Thongprasom K. Number V oral lichen planus: Clinical features and management. Oral Dis. 2005;11(6):338–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01142.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Salazar-Sanchez N. Topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus in the treatment of oral lichen planus: An update. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39(3):201–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00830.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lener EV, Brieva J, Schachter M, West LE, West DP, el-Azhary RA. Successful treatment of erosive lichen planus with topical tacrolimus. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(4):419–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaliakatsou F, Hodgson TA, Lewsey JD, Hegarty AM, Murphy AG, Porter SR. Management of recalcitrant ulcerativeoral lichen planus with topical tacrolimus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(1):35–41. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.120535. https://doi.org/10.1067/mjd.2002.120535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrison L, Kratochvil FJ III, Gorman A. An open trial of topical tacrolimus for erosive oral lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(4):617–20. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.126275. https://doi.org/10.1067/mjd.2002.126275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rozycki TW, Rogers RS III, Pittelkow MR, McEvoy MT, el-Azhary RA, Bruce AJ, et al. Topical tacrolimus in the treatment of symptomatic oral lichen planus: A series of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(1):27–34. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.119648. https://doi.org/10.1067/mjd.2002.119648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olivier V, Lacour JP, Mousnier A, Garraffo R, Monteil RA, Ortonne JP. Treatment of chronic erosive oral lichen planus with low concentrations of topical tacrolimus: An open prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(10):1335–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.10.1335. https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.138.10.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hodgson TA, Sahni N, Kaliakatsou F, Buchanan JA, Porter SR. Long-term efficacy and safety of topical tacrolimus in the management of ulcerative/erosive oral lichen planus. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13(5):466–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swift JC, Rees TD, Plemons JM, Hallmon WW, Wright JC. The effectiveness of 1% pimecrolimus cream in the treatment of oral erosive lichen planus. J Periodontol. 2005;76(4):627–35. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.4.627. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2005.76.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorouhi F, Solhpour A, Beitollahi JM, Afshar S, Davari P, Hashemi P, et al. Randomized trial of pimecrolimus cream versus triamcinolone acetonide paste in the treatment of oral lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):806–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lodi G, Scully C, Carrozzo M, Griffiths M, Sugerman PB, Thongprasom K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: Report of an international consensus meeting. Part 1. Viral infections and etiopathogenesis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100(1):40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.06.077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sciubba JJ. Oral mucosal diseases in the office setting - Part II: Oral lichen planus, pemphigus vulgaris, and mucosal pemphigoid. Gen Dent. 2007;55(5):464–76. quiz 477-8, 488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu V, Mackool BT. Mycophenolate in dermatology. J Dermatolog Treat. 2003;14(4):203–11. doi: 10.1080/09546630310016826. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546630310016826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hodak E, Yosipovitch G, David M, Ingber A, Chorev L, Lider O, et al. Low-dose low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparin) is beneficial in lichen planus: A preliminary report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38(4):564–8. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70118-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng A, Mann C. Oral erosive lichen planus treated with efalizumab. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(6):680–2. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.6.680. https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.142.6.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emslie ES, Hardman FG. The surgical treatment of oral lichen planus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1970;56(1):43–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hovick CJ, Kalkwarf KL. Treatment of localized oral erosive lichen planus lesions with free soft tissue grafts. Periodontal Case Rep. 1987;9(2):21–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamizi M, Moayedi M. Treatment of gingival lichen planus with a free gingival graft: A case report. Quintessence Int. 1992;23(4):249–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katz J, Goultschin J, Benoliel R, Rotstein I, Pisanty S. Lichen planus evoked by periodontal surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1988;15(4):263–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1988.tb01580.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.1988.tb01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malmstrom M, Leikomaa H. Experiences with cryotherapy in the treatment of oral lesions. Proc Finn Dent Soc. 1980;76(3):117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Azizi A, Rezaee M. Comparison of periodontal status in gingival oral lichen planus patients and healthy subjects. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:561232. doi: 10.1155/2012/561232. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/561232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guiglia R, Di Liberto C, Pizzo G, Picone L, Lo Muzio L, Gallo PD, et al. A combined treatment regiment for desquamative gingivitis in patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36(2):110–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00478.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lundquist G, Forsgren H, Gajecki M, Emtestam L. Photochemotherapy of oral lichen planus. A controlled study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79(5):554–8. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80094-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1079-2104(05)80094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Maweri SA, Ashraf S, Kalakonda B, Halboub E, Petro W, AlAizari NA. Efficacy of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of symptomatic oral lichen planus: A systematic review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018;47(4):326–32. doi: 10.1111/jop.12684. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.12684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bakhtiari S, Azari-Marhabi S, Mojahedi SM, Namdari M, Rankohi ZE, Jafari S. Comparing clinical effects of photodynamic therapy as a novel method with topical corticosteroid for treatment of oral lichen planus. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2017;20:159–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.06.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maloth KN, Velpula N, Kodangal S, Sangmesh M, Vellamchetla K, Ugrappa S, et al. Photodynamic therapy - A non-invasive treatment modality for precancerous lesions. J Lasers Med Sci. 2016;7(1):30–6. doi: 10.15171/jlms.2016.07. https://doi.org/10.15171/jlms.2016.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jajarm HH, Falaki F, Sanatkhani M, Ahmadzadeh M, Ahrari F, Shafaee H. A comparative study of toluidine blue-mediated photodynamic therapy versus topical corticosteroids in the treatment of erosive-atrophic oral lichen planus: A randomized clinical controlled trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2015;30(5):1475–80. doi: 10.1007/s10103-014-1694-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-014-1694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saleh WE, Khashaba O, El nagdy S, Moustafa MD. Photodynamic therapy of oral erosive lichen planus in diabetic and hypertensive patients. Mansoura Journal of Dentistry. 2014;1(3):119–23. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mostafa D, Moussa E, Alnouaem M. Evaluation of photodynamic therapy in treatment of oral erosive lichen planus in comparison with topically applied corticosteroids. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2017;19:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.04.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soliman M, Kharbotly AE, Saafan A. Management of oral lichen planus using diode laser (980nm) A clinical study. Egypt Dermatol Online J. 2005;1(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van der Hem PS, Egges M, van der Wal JE, Roodenburg JL. CO2 laser evaporation of oral lichen planus. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37(7):630–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2008.04.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cafaro A, Albanese G, Arduino PG, Mario C, Massolini G, Mozzati M, et al. Effect of low-level laser irradiation on unresponsive oral lichen planus: Early preliminary results in 13 patients. Photomed Laser Surg. 2010;28(Suppl 2):S99–103. doi: 10.1089/pho.2009.2655. https://doi.org/10.1089/pho.2009.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trehan M, Taylor CR. Low-dose excimer 308-nm laser for the treatment of oral lichen planus. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(4):415–20. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.4.415. https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.140.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Doutre MS, Beylot C, Couzigou P, Long P, Royer P, Beylot J. Lichen planus and virus C hepatitis: Disappearance of the lichen under interferon alpha therapy. Dermatology. 1992;184(3):229. doi: 10.1159/000247552. https://doi.org/10.1159/000247552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doutre MS, Couzigou P, Beylot-Barry M, Beylot C, Quinton A. Lichen planus and hepatitis C: Heterogeneity in the course of 6 cases treated with interferon alpha. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1996;20(8-9):709–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Protzer U, Ochsendorf FR, Leopolder-Ochsendorf A, Holtermuller KH. Exacerbation of lichen planus during interferon alpha-2a therapy for chronic active hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 1993;104(3):903–5. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91029-h. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(93)91029-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Areias J, Velho GC, Cerqueira R, Barbêdo C, Amaral B, Sanches M, et al. Lichen planus and chronic hepatitis C: Exacerbation of the lichen under interferon alpha-2a therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8(8):825–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nunez M, Miralies ES, De las Heras ME, Ledo A. Appearance of oral erosive lichen planus during interferon alpha-2a therapy for chronic active hepatitis C. J Dermatol. 1995;22(6):461–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1995.tb03424.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1346-8138.1995.tb03424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nagao Y, Sata M, Ide T, Suzuki H, Tanikawa K, Itoh K, et al. Development and exacerbation of oral lichen planus during and after interferon therapy for hepatitis C. Eur J Clin Invest. 1996;26(12):1171–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1996.610607.x. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2362.1996.610607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schlesinger TE, Camisa C, Gay JD, Bergfeld WF. Oral erosive lichen planus with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis during interferon alpha-2b therapy for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6 Pt 1):1023–5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80296-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-9622(97)80296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zuckerman E, Keren D, Slobodin G, Rosner I, Rozenbaum M, Toubi E, et al. Treatment of refractory, symptomatic, hepatitis C virus related mixed cryoglobulinemia with ribavirin and interferon-alpha. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(9):2172–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnson RJ, Gretch DR, Couser WG, Alpers CE, Wilson J, Chung M, et al. Hepatitis C virus-associated glomerulonephritis: Effect of alpha-interferon therapy. Kidney Int. 1994;46(6):1700–4. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.471. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1994.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sheikh MY, Wright RA, Burruss JB. Dramatic resolution of skin lesions associated with porphyria cutanea tarda after interferon-alpha therapy in a case of chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43(3):529–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1018854906444. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018854906444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lu SY, Lin LH, Lu SN, Wang JH, Hung CH. Increased oral lichen planus in a chronic hepatitis patient associated with elevated transaminase levels before and after interferon/ribavirin therapy. J Dent Sci. 2009;4(4):191–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1991-7902(09)60026-X. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nagao Y, Sata M. Dental problems delaying the initiation of interferon therapy for HCV-infected patients. Virol J. 2010;7:192. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-192. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-7-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pawlotsky JM, Yahia MB, Andre C, Voisin MC, Intrator L, Roudot-Thoraval F, et al. Immunological disorders in C virus chronic active hepatitis: A prospective case-control study. Hepatology. 1994;19(4):841–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.1840190407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nagao Y, Kawaguchi T, Ide T, Kumashiro R, Sata M. Exacerbation of oral erosive lichen planus by combination of interferon and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Int J Mol Med. 2005;15(2):237–41. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.15.2.237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2015. J Hepatol. 2015;63(1):199–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wiznia LE, Laird ME, Franks AG., Jr Hepatitis C virus and its cutaneous manifestations: Treatment in the direct-acting antiviral era. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venererol. 2017;31(8):1260–70. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14186. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Soriano V, Labarga P, Fernandez-Montero JV, Benito JM, Poveda E, Rallon N, et al. The changing face of hepatitis C in the new era of direct-acting antivirals. Antiviral Res. 2013;97(1):36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.10.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, Galati G, Gallo P, De Vincentis A, Riva E, Picardi A. Hepatitis C treatment in the elderly: New possibilities and controversies towards interferon-free regimens. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(24):7412–26. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i24.7412. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i24.7412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nagao Y, Kimura K, Kawahigashi Y, Sata M. Successful treatment of hepatitis C virus-associated oral lichen planus by interferon-free therapy with direct-acting antivirals. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7(7):e179. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.37. https://doi.org/10.1038/ctg.2016.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scott GD, Rieger KE. New-onset cutaneous lichen planus following therapy for hepatitis C with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43(4):408–9. doi: 10.1111/cup.12656. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nagao Y, Tsuji M. The discovery through dentistry of potentially HCV-infected Japanese patients and intervention with treatment. Adv Res Gastroentero Hepatol. 2017;7(3):555711. https://doi.org/10.19080/ARGH.2017.07.555711. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Misaka K, Kishimoto T, Kawahigashi Y, Sata M, Nagao Y. Use of direct-acting antivirals for the treatment of hepatitis C virus-associated oral lichen planus: A case report. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2016;10(3):617–22. doi: 10.1159/000450679. https://doi.org/10.1159/000450679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yoshikawa A, Terashita K, Morikawa K, Matsuda S, Yamamura T, Sarashina K, et al. Interferon-free therapy with sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for successful treatment of genotype 2 hepatitis C virus with lichen planus: A case report. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017;10(3):270–3. doi: 10.1007/s12328-017-0742-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-017-0742-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]