Abstract

Worldwide, obesity is considered as an important public health problem. This study aims to explore the social and economic factors associated with overweight and obesity among women of childbearing age residing in the urban area of Morocco. This is a descriptive and analytical study conducted among women (N=240), aged between 15 and 49 years. At recruitment, socioeconomic status (SES) of each participant was assessed, anthropometric parameters were recorded, and body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) were measured to assess overweight and obesity. Data regarding skipped meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) were collected using an adapted questionnaire. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of childbearing age was 29.9% and 15.4%, respectively, while for abdominal obesity, the prevalence of overweight and obesity was, respectively, 39.9% and 60.1%. The results indicate that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among women is higher in women aged over 30. A significant association was shown between education level and both BMI and WHR (r1=−0.23, r2=−0.17, p < 0.05), respectively, and there is also a significant correlation between household size and WHR abdominal obesity (r=0.21, p=0.05). Our results reinforce the necessity to improve the access of all social classes in Morocco to reliable information on the determinants and consequences of obesity and to develop plans for adequate prevention and management of obesity.

1. Introduction

The worldwide prevalence of obesity has nearly tripled over the past 4 decades and thus has become a global epidemic that is still increasing in both developed and developing countries [1, 2]. In 2016, more than 1.9 billion adults, 18 years and older, were overweight [2]. Of these, over 650 million were obese and 39% of women aged 18 and over were overweight. Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that once developed into a disease may impair human health [3]. Together, they are considered as the fifth most common risk factor for death worldwide and account for at least 2.8 million deaths each year [3]. In addition, they substantially increase the risk of noncommunicable diseases, particularly cardiovascular diseases, endocrine and metabolic disturbances, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, several psychological problems, sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, and certain types of cancer [4, 5].

In Morocco, the prevalence of overweight and obesity is high, particularly in women from urban areas. In fact, the prevalence of overweight and obesity altogether accounted for 42% of women in urban regions and 29% in rural areas (National Survey on Population and Family Health) [6]. This prevalence exceeded 40% in the regions of Grand Casablanca, Oriental, Rabat-Salé-Zemmour-Zaër, and Fès-Boulmane (NSPF, 2003-2004). According to a national survey conducted among Moroccan women, more than 25% were overweight and 11% were obese (NSPF, 2003-2004) [6]. In 2012-2013, indicators showed that women and townspeople have seen their proportion of overweight increase from 29.9% to 34.7% and from 29.2% to 34.9% at the expense of their proportion of normal weight, which decreased from 50.6% to 36.1% and from 54.4% to 40.8%, respectively [7].

Numerous studies have shown a strong influence of socioeconomic status on obesity, particularly in women, causing variations in their behaviors which change their energy intake and energy expenditure and, as a result, affect their body fat storage [8–10]. Thus, this study aims to explore the social and economic factors associated with overweight and obesity among women of childbearing age residing in urban environments in Rabat and, as such, provides information that could help identify the groups most at risk for targeted interventions.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This descriptive and analytical study conducted among women (N=240), aged between 15 and 49 years, lasted 3 months from April to June 2017.

This study included women who were aged between 15 and 49 years and living in the Rabat prefecture and not under any permanent medical treatment. Pregnant and lactating women, women suffering from mental illnesses, or those who participated in the pilot study were excluded from the present study.

The study received the approval of the Ethics Board of the Medicine and Pharmacy Faculty, University of Rabat, Morocco (Ethics no. 69 delivered on 31 January 2017). The purpose and the protocol of the study were presented and explained to the participants. Subsequently, oral and written consent was obtained from women, before the beginning of the survey.

2.2. Site of the Study

The study took place in Rabat which is located along the Atlantic Ocean at the Bouregreg River's outlet. Rabat, the capital of Morocco, is considered the second largest city with an urban population. This region is also known by its high obesity rate (NSPF, 2003-2004) [6].

2.3. Selection of Health Centers

Women were recruited from eight urban health centers that were selected on the basis of the following criteria: accessibility to our field team and large attendance of women enough to cover the required number for the study age range.

2.4. Sample

The study concerns 240 Moroccan women of childbearing age (15 to 49 years), who visited the health centers of Rabat between April and June 2017. Women had to meet the inclusion criteria and provide their consent to participate in the survey.

To calculate the sample size, we used the formula developed by Cochran [11] and Ardilly [12]:

| (1) |

where t is the 95% confidence level, p is the estimated prevalence of the obese population, and m is the margin of error (set at 5%).

The prevalence of obesity in the Rabat-Zemmour-Zaër region is estimated at 14.4% with a margin of error of 5% [6]. Thus, 189 subjects were considered necessary for inclusion to obtain statistically significant results. The total number of women who met the inclusion criteria was 240.

2.5. Data Collection

At recruitment, socioeconomic status (SES) of each participant was assessed, anthropometric parameters were recorded, and BMI, waist circumference, and WHR were measured to assess overweight and obesity. Data regarding skipped meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) were collected using an adapted questionnaire.

2.5.1. Socioeconomic Questionnaire (SES)

The data on socioeconomic standards and living conditions of the women were collected at the beginning of the study by interviewing them. We used an adequate questionnaire that was adapted from other questionnaires used nationally to serve the purpose of our survey [6]. Information collected included the level of education of women, household size, number of children, marital status, household monthly global expenses, and alimentary expenses.

2.5.2. Anthropometric Measurements

The anthropometric parameters of each participant were measured and were taken following the standard procedures used by the WHO [5].

Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a scale (seca 750) with minimal clothing and no shoes. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer (seca). BMI was calculated as a ratio of weight in kg and square height in m2. Women were classified into four groups according to BMI [5, 13]: underweight women with BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2; women in a normal range with a BMI between 18.5 kg/m2 and 24.99 kg/m2; overweight women with a BMI between 25 kg/m2 and 29.99 kg/m2; and obese women with a BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2.

The waist circumference was measured at the approximate midpoint between the lower margin of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest [14]. Hip circumference was measured at the widest point over the buttocks. For abdominal obesity, WHR was obtained by dividing the mean waist circumference by the mean hip circumference. Women with a WHR ≥ 0.85 were classified as obese [5].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 20.0). The distribution for normality of quantitative variables was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The variables normally distributed were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The nominal variables were presented as proportion. The Spearman rank-order correlation was the test used for correlations to describe the linear relationship between two continuous variables. Two-sided p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

The socioeconomic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of women were Arabs, more than 50% do not work, and the prevalence of illiteracy was 13%. Families consist mainly of 4 to 7 persons. More than 40% of families live with more than 366 US$ per month, and 23% spend between 174.39 and 272.32 US$ monthly for food (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socioeconomic characteristics of women of childbearing age.

| Variables | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age strata | ||

| 15 to 19 yrs | 54 | 22.50 |

| 20 to 29 yrs | 66 | 27.50 |

| 30 to 39 yrs | 74 | 30.83 |

| 40 to 49 yrs | 46 | 19.17 |

|

| ||

| Culture | ||

| Arab | 178 | 74.17 |

| Amazigh | 47 | 19.58 |

| Sahrawi | 7 | 2.92 |

| Rifaine | 6 | 2.50 |

| Jebli | 2 | 0.83 |

|

| ||

| Level of education | ||

| Illiterate | 32 | 13.33 |

| Primary | 35 | 14.58 |

| Secondary | 109 | 45.42 |

| Higher education | 64 | 26.67 |

|

| ||

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 87 | 36.25 |

| Married | 145 | 60.42 |

| Divorced | 7 | 2.92 |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.41 |

|

| ||

| Occupation of women | ||

| Without job | 142 | 59.17 |

| Student | 52 | 21.67 |

| With job | 46 | 19 .16 |

|

| ||

| Occupation of the household head | ||

| Without job | 8 | 3.33 |

| With job | 230 | 95.83 |

| Retired | 2 | 0.84 |

|

| ||

| Number of children | ||

| No children | 92 | 38.33 |

| 1 to 2 children | 93 | 38.75 |

| 3 and more | 55 | 22.92 |

|

| ||

| Household size | ||

| <4 people | 57 | 23.75 |

| 4 to 7 people | 165 | 68.75 |

| >7 people | 18 | 7.50 |

|

| ||

| Housing type | ||

| Cement | 229 | 95.42 |

| Hard | 11 | 4.58 |

|

| ||

| Monthly expenses | ||

| Lower than 122 US$ | 2 | 0.83 |

| 122 to 195 US$ | 12 | 5.00 |

| 196 to 244 US$ | 30 | 12.50 |

| 244 to 366 US$ | 28 | 11.67 |

| Higher than 366 US$ | 99 | 41.25 |

| Not known | 69 | 28.75 |

|

| ||

| Monthly expenses for food | ||

| Lower than 65.36 US$ | 10 | 4.2 |

| 65.47 to 98.03 US$ | 12 | 5.0 |

| 98.14 to 130.71 US$ | 17 | 7.1 |

| 130.82 to 174.28 US$ | 51 | 21.3 |

| 174.39 to 272.32 US$ | 55 | 23.0 |

| Higher than 272.32 US$ | 25 | 10.5 |

| Not known | 69 | 28.9 |

The anthropometric parameters of participants are reported in Table 2. The mean age was 30.0 ± 9.9 years, with a mean weight of 64.0 ± 12.6 kg and an average height of 1.6 ± 0.1 cm. For body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (HC), hip circumference, and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) in women, the average was 24.7 ± 4.8 kg/m2, 83.4 ± 12.9 cm, 99.4 ± 12.0 cm, and 0.8 ± 0.1 cm, respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics of anthropometric parameters of the studied population.

| N | Mean ± SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 240 | 30.0 ± 9.9 | 15 | 49 |

| Weight (kg) | 240 | 64.0 ± 12.6 | 39 | 105 |

| Height (m) | 240 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.5 | 1.8 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 240 | 24.7 ± 4.8 | 15 | 41 |

| WC (cm) | 240 | 83.4 ± 12.9 | 57 | 118 |

| HC (cm) | 240 | 99.4 ± 12.0 | 43 | 126 |

| WHR (cm) | 240 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

Note. BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; HC: hip circumference; WHR: waist-to-hip ratio.

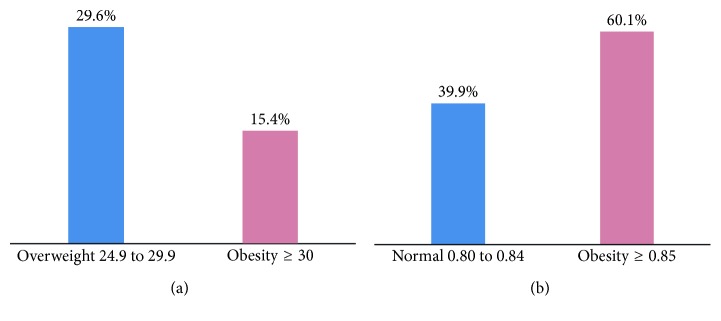

The classification of BMI and WHR is summarized in Figure 1. According to BMI, 29.6% of women were overweight and 15.4% were obese, while according to their WHR, almost 40% of women were not abdominally obese and 60.1% were abdominally obese (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overweight and obesity of women enrolled in the study. (a) BMI (kg/m2). (b) WHR (cm).

Table 3 shows the anthropometric parameters of women of childbearing age by age strata. The results indicate that the mean of body mass index increased from the age of 30 (26.6 ± 4.3 kg/m2).

Table 3.

Anthropometric parameters of participants by age strata.

| N | Age | Weight | Height | BMI | WC | HC | WHR | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–19 yrs | 54 | 17.4 ± 1.3 | 56.4 ± 10.4 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 21.8 ± 3.7 | 74.8 ± 9.5 | 93.7 ± 11.0 | 0.80 ± 0.1 | <0.0001 |

| 20–29 yrs | 66 | 24.3 ± 2.6 | 61.7 ± 13.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 23.5 ± 4.4 | 80.3 ± 12.4 | 97.1 ± 12.2 | 0.80 ± 0.1 | <0.0001 |

| 30–39 yrs | 74 | 35.4 ± 2.9 | 68.4 ± 11.3 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 26.6 ± 4.3 | 88.1 ± 12.2 | 102.9 ± 12.4 | 0.90 ± 0.1 | <0.0001 |

| 40–49 yrs | 46 | 44.0 ± 3.0 | 69.2 ± 10.8 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 27.1 ± 4.6 | 90.5 ± 11.3 | 103.9 ± 8.7 | 0.90 ± 0.1 | <0.0001 |

Note. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; HC: hip circumference; WHR: waist-to-hip ratio. p value compared the anthropometric parameters by age strata using the ANOVA one-factor test.

Table 4 shows the correlation between obesity and the socioeconomic status of participants. The analysis demonstrates the existence of a significant correlation between several variables. Indeed, the first correlation exists between age and BMI (r=0.43, p < 0.05) and WHR (r=0.25, p < 0.05). Another significant relationship was shown between education level with BMI and with WHR (r1=−0.23, r2=−0.17, p < 0.05), respectively. The same observation was found for marital status with BMI and with WHR (r=0.43, r2=0.15, p < 0.05). Finally, there is also a significant correlation between household size and WHR abdominal obesity (r=0.21, p=0.05).

Table 4.

Association between anthropometric measures and socioeconomic status in studied women.

| Variables | Weight | Height | BMI | WC | HC | WHR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=240) | (n=240) | (n=240) | (n=240) | (n=240) | (n=240) | ||

| Age strata | R | 0.39 | −0.07 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.25 |

| p value | 0.000∗ | 0.248 | 0.000∗ | 0.000∗ | 0.000∗ | 0.000∗ | |

|

| |||||||

| Culture | R | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.09 |

| p value | 0.815 | 0.946 | 0.912 | 0.478 | 0.906 | 0.162 | |

|

| |||||||

| Level of education | R | −0.17 | 0.14 | −0.23 | −0.29 | −0.19 | −0.17 |

| p value | 0.010∗ | 0.029∗ | 0.000∗ | 0.000∗ | 0.003∗ | 0.008∗ | |

|

| |||||||

| Marital status | R | 0.38 | −0.03 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.15 |

| p value | 0.000∗ | 0.623 | 0.000∗ | 0.000∗ | 0.000∗ | 0.023∗ | |

|

| |||||||

| Occupation of women | R | −0.09 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.03 |

| p value | 0.165 | 0.796 | 0.132 | 0.290 | 0.211 | 0.615 | |

|

| |||||||

| Occupation of the household head | R | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.02 |

| p value | 0.901 | 0.223 | 0.587 | 0.396 | 0.537 | 0.806 | |

|

| |||||||

| Number of children | R | 0.43 | −0.06 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.42 | 0.19 |

| p value | 0.000∗ | 0.337 | 0.000∗ | 0.000∗ | 0.000∗ | 0.003∗ | |

|

| |||||||

| Household size | R | −0.11 | −0.16 | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.14 | 0.21 |

| p value | 0.086 | 0.015∗ | 0.391 | 0.686 | 0.034∗ | 0.001∗ | |

|

| |||||||

| Housing type | R | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| p value | 0.734 | 0.437 | 0.572 | 0.764 | 0.803 | 0.723 | |

|

| |||||||

| Monthly expenses | R | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.08 |

| p value | 0.608 | 0.130 | 0.285 | 0.804 | 0.659 | 0.206 | |

|

| |||||||

| Monthly expenses for food | R | −0.09 | 0.08 | −0.12 | −0.08 | −0.03 | −0.10 |

| p value | 0.186 | 0.199 | 0.067 | 0.243 | 0.679 | 0.125 | |

BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; HC: hip circumference; WHR: waist-to-hip ratio; r: correlation coefficient. ∗The correlation is significant at the level of 0.05 (bilateral).

Table 5 shows overweight and obesity among women skipping meals. Data analysis clearly demonstrated that 16.2% of women skipping breakfast were obese. However, more than 20% of women skipping dinner were overweight (Table 5). Indeed, more than 90% of women who were not skipping breakfast were overweight and 83.3% were obese.

Table 5.

Overweight and obesity among women who are (or are not) skipping meals.

| Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |

| Women skipping meals | ||||||

| Overweight | 4 | 5.6 | 3 | 4.2 | 20 | 28.2 |

| Obesity | 6 | 16.2 | 1 | 2.7 | 5 | 13.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Women not skipping meals | ||||||

| Overweight | 67 | 94.4 | 68 | 95.8 | 51 | 71.8 |

| Obesity | 31 | 83.8 | 36 | 97.3 | 32 | 86.5 |

∗Results are presented as proportion. Overweight: 24.9 to 29.9 kg/m2; obesity: 29.9 to 34.9 kg/m2.

4. Discussion

The study was designed to investigate the relationship between socioeconomic status, overweight, and obesity in Moroccan women. Our results showed that according to the body mass index, 29.6% of women were overweight and 15.4% were obese. These prevalences are considered higher than those reported in the 2003-2004 survey [6]. These results remain similar in the national studies [15, 16] and in other studies such as the meta-analysis carried out in the eastern Mediterranean region (EMRO) [17].

In our study, the prevalence of abdominal obesity is higher than the prevalence of overall obesity. Nowadays, excess weight is identified as an important risk factor for many noncommunicable diseases [18]. Indeed, several advances have been made in our understanding of the factors that contribute to obesity, such as the potential role of metabolic factors including the variations in energy expenditure and the identification of some genetic polymorphisms [19, 20]. According to our study, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among women is higher in women aged over 30. The authors from different countries previously published similar results. Indeed, similar observations were made in a prospective study conducted among Swedish women [21], in a study conducted in a Ghanaian population [22], and in a study in Nigeria [23].

On the contrary, several studies have highlighted the inverse association between socioeconomic status (SES) and risk of overweight and obesity. SES is commonly measured by the level of education, occupational status, and income [24, 25] corresponding to different potential individual mechanisms influencing lifestyle factors, such as having a healthy diet, regular physical activity, maintaining a healthy weight, and not smoking [26]. It would seem that married women are more susceptible to be overweight or obese. Marriage is a strong predictor that can contribute to women's obesity [28, 29]. This has been demonstrated by previous studies [15, 23, 27, 28]. In fact, this can be explained by the fact that fat is accumulated during subsequent pregnancies [29].

Education level is considered to influence obesity-related health behaviors, such as specific dietary pattern, physical exercise, smoking habits, and health- and nutrition-related knowledge and beliefs. Data analysis showed a negative correlation between education level and both general and abdominal obesity. These findings are consistent with the results of a survey conducted in 2011, which showed that the prevalence of obesity among adults with low levels of education is twice as high as that among adults with higher levels of education [7]. This can be explained by the fact that illiteracy or a low level of education seems to be another factor in obesity. Illiterate women are not aware of the consequences of obesity and the risk of unhealthy eating habits on health [29, 30]. These consequences are manifested in women of reproductive age in general by the risk of chronic disease [31]. At the reproductive level, overweight and obesity have been shown to be associated with negative reproductive health outcomes, thus reducing the efficacy of infertility treatment as well [31, 32].

These results are aligned with those from the study undertaken in 2009 proving that the fact of skipping meals disrupts the hormonal and digestive secretions, leading to an increase in energy “storage” and therefore to a weight increase [4]. Similarly, a study conducted among Swedish population showed that being obese was significantly associated with omitting breakfast (OR 1.41 (1.05–1.90)), omitting lunch (OR 1.31 (1.04–1.66)), and eating at night (OR 1.62 (1.10–2.39)) [33]. On the contrary, many observational studies have found that breakfast frequency is inversely associated with obesity and chronic disease [34]. Studies have suggested that eating breakfast everyday is associated with having a healthy body weight [35].

5. Conclusion

Our results reinforce the necessity to improve the access of all social classes in Morocco to reliable information on determinants and consequences of obesity and to develop plans for adequate prevention and management of obesity, taking into account the socioeconomic and environmental factors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to acknowledge all women and investigators who participated in this study. They would also like to gratefully acknowledge the health workers and other support staff.

Abbreviations

- SSE:

Socioeconomic status

- BMI:

Body mass index

- WC:

Waist circumference

- HC:

Hip circumference

- WHR:

Waist-to-hip ratio

- HCP:

Haut Commissariat au Plan

- SPSS:

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- EMRO:

Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. Geneva, Switzerland: Organisation Mondiale de la Santé; 2003. Obésité : prévention et prise en charge de l‘épidémie mondiale. Rapport d’une Consultation de l’OMS. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2018. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. 10 Faits Sur L’obésité. Geneva, Switzerland: Organisation Mondiale de la Santé; 2017. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/obesity/fr/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chevallier L. Nutrition: Principes et Conseils. 3rd. Paris, France: Elsevier Masson; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2000. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Technical Report Series, No. 894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministère de la Santé. Enquête sur la population et la santé familiale 2003-2004. 2005. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR155/FR155.pdf.

- 7.Haut-Commissariat au Plan. Les Indicateurs Sociaux 2012-2013. Casablanca, Morocco: Haut-Commissariat au Plan; 2016. https://www.hcp.ma/region-drda/attachment/834622/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobal J., Stunkard A. J. Socioeconomic status and obesity: a review of the literature. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;105(2):260–275. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sundquist J., Johansson S. E. The influence of socioeconomic status, ethnicity and lifestyle on body mass index in a longitudinal study. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;27(1):57–66. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y. Cross-national comparison of childhood obesity: the epidemic and the relationship between obesity and socioeconomic status. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;30(5):1129–1136. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochran W. G. Sampling Techniques. 3rd. New York, NY, USA: Wiley & Sons; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ardilly P. Les Techniques de Sondage. 2nd. Paris, France: Edition Technip; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institutes of Health. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: the evidence report. Obesity Research. 1998;6(2):S51–S210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO. WHO STEP Wise Approach to Surveillance (STEPS) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jafri A., Jabari M., Dahhak M., Saile R., Derouiche A. Obesity and its related factors among women from popular neighborhoods in Casablanca, Morocco. Ethnicity and Disease. 2013;23(3):369–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belahsen R., Mziwira M., Fertat F. Anthropometry of women of childbearing age in Morocco: body composition and prevalence of overweight and obesity. Public Health Nutrition. 2003;7(4):523–530. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musaiger A. O. Overweight and obesity in eastern mediterranean region: prevalence and possible causes. Journal of Obesity. 2011;2011:17. doi: 10.1155/2011/407237.407237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fezeu L., Minkoulou E., Balkau B., et al. Association between socioeconomic status and a diposity in urban Cameroon. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35(1):105–117. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stunkard A. J., Sorensen T. I., Hanis C., et al. An adoption study of human obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;314(4):193–198. doi: 10.1056/nejm198601233140401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogler G. P., Sorensen T. I., Stunkard A. J., Srinivasan M. R., Rao D. C. Influences of genes and shared family environment on adult body mass index assessed in an adoption study by a comprehensive path model. International Journal Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 1995;19(1):40–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lahmann P. H., Issner L. L., Gullberg B., Berglund G. Sociodemographic factors associated with long-term weight gain, current body fatness and central adiposity in Swedish women. International Journal of Obesity. 2000;24(6):685–694. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amoah A. G. Obesity in adult residents of Accra, Ghana. Ethnicity and Disease. 2003;13(2):S97–S101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okoh M. Socio-demographic correlates of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2013;17(4):66–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krieger N., Williams D. R., Moss N. E. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies and guidelines. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;18:314–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wardle J., Waller J., Jarvis M. J. Sex differences in the association of socioeconomic status with obesity. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(2):1299–1304. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiuve S. E., McCullough M.-L., Sacks F. M., Rimm E. B. Healthy lifestyle factors in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease among men benefits among users and nonusers of lipid-lowering and antihypertensive medications. Circulation. 2006;114:160–167. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.106.621417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahim S., Baali A. Etude de l’obésité et quelques facteurs associés chez un groupe de femmes marocaines résidentes de la ville de Smara (sud du Maroc) Antropo. 2011;24:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rguibi M., Belahsen R. Overweight and obesity among urban Saharaoui women of south Morocco. Ethnicity and Disease. 2004;24:43–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sellam E., Bour A. Etat nutritionnel chez des femmes de l’oriental marocain (préfecture d’Oujda-Angad) Antropo. 2014;31:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mokhtar N., Elati J., Chabir R., et al. Diet culture and obesity in northern Africa. American Society for Nutritional Sciences. 2001;131(3):887–892. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.887S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cogswell M. E., Perry G. S., Schieve L. A., Dietz W. H. Obesity in women of childbearing age: risks, prevention, and treatment. Primary Care Update for Ob/Gyns. 2001;8(3):89–105. doi: 10.1016/S1068-607X(00)00087-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogbuji Q. C. Obesity and reproductive performance in women. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2010;14(3):143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg C., Lappas G., Wolk A., et al. Eating patterns and portion size associated with obesity in a Swedish population. Appetite. 2009;52(1):21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timlin M. T., Pereira M. A. Breakfast frequency and quality in the etiology of adult obesity and chronic diseases. Nutrition Reviews. 2007;65(6):268–281. doi: 10.1301/nr.2007.jun.268-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenkins D. J., Jebkins A. L., Wolever T. M., et al. Low glycemic index: lente carbohydrates and physiological effects of altered food frequency. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1994;59(3):706S–709S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.3.706S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.