Abstract

In many parts of the world, vulnerable patient populations may be cared for by a clinical nurse specialist (CNS). Nurses desiring to develop themselves professionally in the clinical arena, within the specialty of their choice, have the opportunity to obtain the knowledge, skills, experience and qualifications necessary to attain advanced practice positions such as CNS or nurse consultant (NC). Although studies have demonstrated the benefits of such roles and while the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends it, advanced nursing practice is not yet integrated into the health care culture in Saudi Arabia. The reasons for this are multiple, but the most important is the poor image of clinical nursing throughout the country. This article aims to share a perspective on CNS practice, while casting light on some of the obstacles encountered within Saudi Arabia. A model is proposed representing specialist nurse–physician collaborative practice for implementation nationally. The model has been implemented in the care of the colorectal and stoma patient populations while taking into consideration patient population needs and local health care culture. This model is based on the concepts of holistic “patient-centered care”, specialist nurse–physician collaborative practice, and the four practice domains for NCs (expert practice, leadership, research and education) as indicated by the Department of Health in the United Kingdom. We suggest this model will enable the introduction of advanced specialist nursing and collaborative partnerships in Saudi Arabia with benefits for patients, physicians, health care organizations and the nursing profession as a whole.

Despite studies demonstrating the benefits of involving clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) in the care of complex and vulnerable patient populations,1,2 these positions are sadly lacking in Saudi Arabia. In 2008, there were 393 hospitals representing 53 888 beds, and a nursing workforce of 101 298; of them, 29.1% were Saudi nurses.3 Yet, there were only two qualified colorectal/stoma CNSs, known to be working in clinical practice within the country. This discrepancy may be attributed to the low numbers of Saudi nurses, the lack of recognized post basic or postgraduate specialist nursing education programs within the Kingdom, and the poor financial and career incentives available to CNSs. These factors are possibly a result of the poor image of clinical nursing in Saudi Arabia.

This article gives a perspective of CNS practice while highlighting the obstacles within the country; it describes a CNS–physician collaborative practice model applied to the field of colorectal and stoma patient care in Saudi Arabia. It sheds light on the concepts of “patient-centered care”, specialist collaborative practice, and the four practice domains for nurse consultants (NCs) in the United Kingdom (UK).

Specialist Nursing Practice

Internationally, there is confusion surrounding the titles, roles and educational requirements for expert nurses.4,5 For the sake of clarity, expert nurses will include advanced practice nurses (APNs), nurse practitioners (NPs), CNSs and NCs. In the UK and the United States (US), these titles may all represent nurses in advanced practice roles, but APNs and NPs tend to be utilized to “substitute” physician roles in both acute and primary care settings, while CNSs and NCs are said to be “supplementary” to the physicians while being responsible for very specific patient populations.2,6 According to the American Nurses Association, CNSs provide autonomous specialized nursing care that is evidence based with integration of knowledge into assessment, diagnosis and treatment. Moreover, CNSs construct and execute both patient-specific and population-based programs of care.7 As such, CNSs are suitable for the roles of patient advocate, consultant, and researcher. Their expertise is a function of their ability to demonstrate advanced knowledge and technical skills due to their specialty qualifications and experience.8

The role of the CNS is well established in developed countries; it was implemented in the US in the 1950s and in the UK in the 1970s.9 The role of the NC was introduced in the UK in 1999 as the highest grade of the clinical career ladder, with the aim to promote excellence in quality patient care, while encouraging research within specialized fields by facilitating experienced specialist nurses to advance their career while staying in clinical practice.10 NCs are more likely to be involved in initiatives at a national level. There are four essential domains of the NCs’ role as described by the Department of Health in the UK: expert practice, education, research and leadership.10

Expertise is central to the role of the CNS, yet authors have found it difficult to explain how it is utilized. Manley and colleagues have developed an explanatory framework based around the central theme of “professional artistry” defined as the use of “cognitive, intuitive and sense modes of perception”. The authors state that professional artistry is aided by “holistic practice knowledge”, “knowing the patient/client”, “moral agency”, “saliency” and “skilled know-how.”11 It is likely that experienced CNSs utilize emotional intelligence to reach patients on an intimate human level in order to guide the development of necessary coping mechanisms or characteristics that help them deal with trauma, illness and disability.11

Impact of Specialist Nursing Practice on Patient Care

Many researchers have found that the inclusion of CNSs in the care of patients improves patient satisfaction12–18 related to improved standards and quality of care and better multidisciplinary team communication.13–15,19 CNSs influence all aspects of the patient care environment including facilitating functionality of the multidisciplinary team.20 An audit of patient satisfaction with CNS-led services after ileoanal pouch surgery found that 90% of patients were very satisfied with this service.16 The same was also found in patients attending nurse-led genitourinary clinics.15 In a study of diabetes nurse-led clinics, it was found that CNSs reduced the 10-year disease risk scores by managing uncontrolled hypertension compared to usual care.21 Hill et al compared care provided by CNSs and a junior doctor; patients with rheumatoid arthritis had higher scores for patient satisfaction and improved quality of care in the CNS group.14 Nurses specializing in inflammatory bowel disease in the UK have managed to reduce outpatient visits and hospital admissions by being the first point of contact for patients worried about deterioration in their condition.22 In a study on the impact of rheumatology nurse specialists, the group of patients seen by a CNS were shown to be better able to cope with their disease with improved levels of well-being.13 In a randomized controlled trial comparing usual physician care to physician and nurse specialist care of patients with heart failure, there were fewer deaths, readmissions, and hospital stay days in the group cared for by the physician–nurse specialist group.23 Hill et al. found that arthritic patients followed by a CNS had lower pain levels, less morning stiffness, better physical function and improved self-efficacy.17 Some studies have also found decreased morbidity and/or mortality. Brooten et al. studied women at risk of low birth weight infants and discovered that women cared for by CNSs had fewer infant deaths, fewer complications and hospitalizations. 24 Wheeler compared units with and without CNSs caring for patients undergoing knee replacements. Patients cared for on units covered by CNSs had fewer complications and a reduced length of stay.25

Impact of Specialist Nursing Practice on Health Care Organizations

According to a report published by the Royal College of Nursing, CNSs in the National Health Service (NHS) of the UK decrease financial expenditure by implementing innovative practices.19 Some of these savings involve the prevention or the early recognition of adverse events or complications related to treatments, with estimated savings of approximately £175 168 per nurse annually.19 The implementation of telephone advice lines by CNSs for rheumatology patients is estimated to have saved primary care services in the UK £72 588 per nurse per year.19 The implementation of a childhood epilepsy CNS service in the UK has reduced admissions by half.26 In the study mentioned earlier by Brooten et al, looking at women at risk of delivering low birth weight babies, CNSs reportedly saved $2 500 000 in hospital costs.24 In a qualitative study from a health care providers’ perspective, findings included a positive impact on patient care, including increased patient satisfaction, improved quality of care and decreased outpatient waiting times, emergency room visits and admissions. They also found widespread support for these roles by nurse executives.27

Obstacles to Specialist Nursing Practice

The literature documents the many obstacles encountered by CNSs and NCs during the implementation of their role and in the provision of services.9,28 Authors have written about the lack of support and recognition, their struggle to obtain the necessary resources needed to do their job well, and how they constantly have to justify their positions, which is difficult when much is “hidden work”.4,9,28,29 CNSs are rarely provided clerical or administrative assistance which keeps the CNS away from the bedside.19 This is directly related to the lack of authority given to CNSs, as opposed to nurse administrators.28 While it is important that CNSs are not considered members of the administrative team, they must be supported in order to make and enforce change within their specialty.28 CNSs are reported to feel isolated, often being the only nurse for that specialty within a facility or health care area, with few role models or mentors.9,30 The complex, diverse, individualized and adaptive nature of these specialist roles makes it difficult for nurse administrators to understand or evaluate CNSs and the services they provide.29,31 All in all, this leads to a lack of recognition for the significance of the role of the CNS within organizations and of their benefit to the patient population.19

The Saudi Arabian Perspective

Saudi health care is primarily provided via a national governmental health service, with a minor share provided by the private sector. Care is disjointed across the continuum with limited community services, few family practitioners, community midwives or health visitors. Rehabilitation centers, hospices and facilities for care of the elderly and the mentally ill are also lacking. Home health care services are provided by a few larger hospitals limited geographically to small catchment areas. Patients often have to travel long distances by air or road to receive specialized care at tertiary care centers. Although progress is ongoing, patients nationally have little access to health promotion and disease prevention information or screening. Many patients live in rural areas, are illiterate or have a low level of education, limiting their access to information available on the internet or via written media. Saudi Arabia has a diverse population with a rich culture and a strong traditional health belief system. Many of the older generation, particularly those living in rural areas, have a basic mistrust of modern medicine with a preference to use traditional medicine including herbal remedies and cautery. Others lack self-efficacy and prefer to hand over decision making and care to family members or health care professionals. There is a need in Saudi Arabia for vulnerable patients with chronic and complex conditions to receive continuity of care, including holistic physical, psychological, and emotional support, education, advice, and counseling. There is also a need for national collaboration to develop standards and guidelines and to facilitate patient support and advocacy groups. Experienced nurse specialists could be an invaluable resource in achieving these goals within the Kingdom.

Obstacles Facing Nursing in Saudi Arabia

There are many obstacles preventing the growth of specialist nursing within Saudi Arabia; although medicine and medical technology is advanced, nursing is still in its infancy. The majority of nurses employed in the country are expatriates. Nurses in this multinational, multicultural workforce have differing experiences of patient care, collaborative practice, levels of autonomy, and accountability.32 This is the end product of various levels and standards of nursing education and the cultural differences inherent within multicultural nursing communities. The first college of nursing in Saudi Arabia was opened in the 1970s; while universities now offer bachelors and masters degrees in nursing, they do not offer advanced practice courses or specialist postgraduate education programs for Saudi nurses to develop themselves in specialist clinical practice. Salaries and grades are not competitive enough to recruit experienced qualified international CNSs. It is important that CNSs be recognized as experts by their clients: patients and physicians. Attaining this form of respect is difficult in a society where there is a poor image of clinical nursing, no clinical career ladder to match administrative and educational ladders, few avenues to obtain the specialist academic qualifications required and where health care management is primarily dominated by male physicians utilizing the medical model of care.32–36 This is reinforced by the reluctance of physicians, patients, and health care organizations to support advanced nursing practice.

A Model for Clinical Nurse Specialist–Physician Collaborative Care in Saudi Arabia

A shared vision to provide a high standard of specialist care via a center of excellence for the colorectal and stoma patient population in Saudi Arabia, and passion for the stoma/colorectal specialty, are the foundations for the conceptualization of this CNS–physician collaborative model. Internationally, the stoma/colorectal patient population may be cared for by various CNSs in addition to stoma therapists depending on their complaint. In view of the lack of CNSs nationally, this would prove difficult to achieve using traditional CNS models.

The Colorectal Surgery/Stoma Patient Population

Individuals of all ages with fecal or urinary stomas or enterocutaneous fistula.

Adults with colorectal cancer.

Adults with inflammatory bowel disease requiring surgery.

Individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis and their families requiring screening and follow-up.

Individuals with defecatory disorders including fecal incontinence and chronic constipation.

Individuals with other benign colorectal and anal conditions.

Patient Population Needs

Timely, culturally appropriate, and safe assessment, investigation, diagnosis, treatment, and evaluation of treatments and therapies including follow-up care and screening.

Expert, specialized, evidence-based, and holistic care.

Care coordination and collaborative treatment planning.

Compassionate, empathetic, supportive advice and counseling in a therapeutic relationship.

Advocacy.

Empowerment: Input into decision making, provision and access to education and information, encouragement of self-care and self-reliance.

Contact with, and remote access to, appropriate team members.

Access to appropriate and reliable resources, supplies and equipment.

Access to care and assistance with navigation around their plan of care and the health care system.

Patient-centered Care

“Patient-centered care”, as described by Frampton and colleagues,37 is central to our vision, and is based on the concepts of patient empowerment and partnership. Hospitals in general cater for the masses and it is up to health care professionals to understand and advocate for the needs of their specific patient population, ensuring that wherever possible individual values, needs, wishes, and plans are catered for. The colorectal patient population is provided with written information regarding their condition; in addition, all treatment and care plans are discussed with them. They are given every opportunity to be involved in the decision-making process. Family conferences are common. Patients’ views are considered when making decisions regarding the purchase of stoma supplies and equipment. They are also included in the annual colorectal forum where patient issues are discussed. A newsletter for individuals with a stoma is facilitated by the team. A group of stoma patient volunteers also act as a resource and advocacy group. A telephone and email advice line has been established, allowing patients or their families to have easy access to advice, education, and information. It has been noted by others that these services help improve patient satisfaction, and reduce emergency room visits and readmissions.19,38

Clinical Nurse Specialist–Physician Collaboration

The surgeons and CNSs work together in a collaborative collegial relationship, with equality in decision-making power and problem solving, where honest open communication and; respect rules. A better understanding of the others’ role has led to better team cohesion, collaboration, respect and partnership. Partnership between CNSs and physicians is necessary for the provision of safe and effective patient care.30,39,40 Storch and Kenny state that their inability to collaborate may lead to a failure in medical care; they also suggest that we consider collaboration “shared moral work on behalf of the patient”.41 This partnership is only possible when nurses demonstrate their unique specialized nursing knowledge and skill, while physicians welcome and support the growth of an advanced level of nursing, recognizing the nursing hierarchy and knowledge base, which is different, but not inferior to the medical hierarchical system. Individuals who practice under the belief that the nurse is only a vehicle through which orders are executed should consider the cost and wasted years of university education and clinical training.42 Arguments over roles and functions are deleterious to the patients’ experience and obstructive to the provision of care. Early in the relationship, roles and functions should be clearly defined and agreed upon, while ensuring that the knowledge and skills of both the physician and the CNS are utilized to their fullest extent.43 When this partnership is optimized, it is a powerful force for initiating change and driving patient-centered care within an organization.44

The CNSs and surgeons collaborate on provision of care. At monthly meetings, team members voice their views and make recommendations for service development, education and research. Although the CNSs answer to nursing executives, the head of section for colorectal surgery also provides clinical supervision for the development of advanced practice skills. Collaborative inpatient rounds are carried out twice each week, and surgeons and CNSs consult each other in relation to their specialist skills and knowledge on a daily basis. There are commonalities in the expertise, knowledge, and skills utilized by both CNSs and surgeons, but their roles are complimentary, productive and efficient. The CNSs do not “substitute” the role of the colorectal surgeon but “complement” it by providing specialist holistic nursing expertise. Executive support is crucial to clarify roles, develop career pathways, obtain resources, support improvement, approve policies and guidelines for change and approve privileges for advanced practice (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Colorectal model for specialist nurse–physician collaborative care.

Domains of Practice

These are adapted from the four domains of practice for NCs in the UK.10 Expert practice, which is evidence based, reflects the philosophy of holistic care, and is of a specialist nature. The colorectal CNSs are certified, experienced, and demonstrate advanced practice and critical thinking skills in clinical practice. They are recognized as experts and are widely consulted both within the hospital and at a national level.

Leadership includes consultancy, service development according to population needs, guideline development, facilitation of change, and being a role model for other health care professionals. Continuous improvement and change implementation has led to the development of nurse-led clinics in stoma therapy and defecatory disorders; hospital-wide guideline development in stoma therapy and wound care; the provision of a nurse-led colorectal patient advice line, a stoma newsletter and a patient advocacy group. CNSs are also involved in developing hospital policy and models of care.

Research initiation and facilitation includes the evaluation of clinical inquiry and evidence-based practice. Colorectal CNSs and surgeons initiate and support both specialist nursing and medical research.

Education is provided both formally and informally for nurses, physicians, and other health care providers. The CNSs direct and supervise an internationally recognized diploma program in enterostomal therapy, while the colorectal surgeons provide fellowship programs for colorectal surgeons. Workshops and forums are presented both locally and nationally. Collaboration is necessary for the success of these programs.

The Colorectal Program – Structure and Function

A colorectal therapy nursing program includes CNSs and additional staff who support the function and scope of the program. Members of the colorectal therapy team are recruited based on their suitability and motivation to provide empathetic, compassionate patient-centered care. The colorectal therapy team is guided, motivated and led by the Clinical Specialist Director whose role is similar to that of a NC in the UK, with additional leadership responsibilities. The Clinical Specialist Director answers to nursing executives, but works closely with the head of section for colorectal surgery in a matrix structure to ensure that all functions for specialized “patient-centered care” are catered for and that interdisciplinary collaboration is at the center of patient care and service delivery. This matrix structure allows the Clinical Specialist Director to remain in clinical practice while providing the vision, guidance and focus for common goals and patient-centered care in a coordinated manner. Team members are expected to be work-driven and self-motivated with a high degree of independence.

Career Pathway – Clinical Grading Ladder

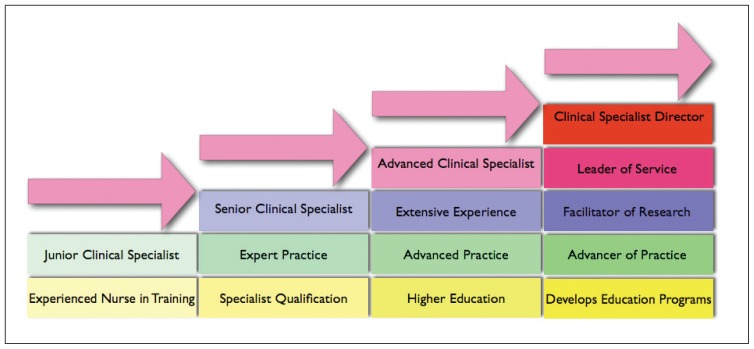

The CNS–Physician Collaborative Colorectal Care Model utilizes a clinical grading ladder that allows for financial rewards for expertise, experience, specialization, higher qualifications, and increased responsibility (Figure 2). It is based on Benners’ novice to expert theory:45

Figure 2.

Career pathway – CNS clinical grading ladder.

Junior Clinical Specialist: An experienced general nurse starting in the specialist field.

Senior Clinical Specialist: An experienced nurse with specialist qualifications, experience, and skills.

Advanced Clinical Specialist: An experienced clinical specialist with a higher level of education, performing independently at an advanced practice level.

Clinical Specialist Director: An experienced advanced clinical specialist with additional responsibility for leadership of the colorectal team, for the development of patient services and educational programs, for the initiation and facilitation of research, and for the advancement of the specialty both in search of excellence in care and evidence-based practice at a local and national level.

In the provision of patient-centered care for the colorectal patient population, additional roles are demanded that are not provided by the colorectal CNSs. These roles are the following:

Clinical Unit Assistant: Translates during patient care delivery via the telephone and email advice line, is responsible for translation of educational material, and assists with supply acquisition.

Patient Advisor: Provides education, advice and counseling including a postoperative telephone follow-up service for all operated patients.

Colorectal Registrar: Will develop and manage the colorectal hereditary disease registry, which does not as yet exist in Saudi Arabia.

Tumor Board Coordinator: Coordinates care for the colorectal cancer patients and facilitates the tumor board meetings.

Discussion

The Saudi health care system is facing immense challenges, amongst which is the lack of Saudi nurses who currently comprise only 29.1% of the workforce.3 The major obstacle is a society struggle over its norms and values with regard to allowing women to work in a mixed-gender environment. This reduces the attractiveness of nursing as a career for Saudi women. However, the new millennium carries far more complex issues than the issue of recruitment.

As health care in Saudi Arabia improves, and modern medicine is availed by a wider society, the aging population is increasing as is the demand for tertiary, chronic and complex care facilities. The prevalence of diabetes has increased from 4.3% in 198746 to 23.7% in 2004.47 The National Cancer Registry recorded an age–sex adjusted rate of around 83 per 100 000 in 200648 compared with 7.4 in 1980.49 This rise in complex tertiary and chronic conditions has created an urgent need for highly specialized and expert nursing care. The health care infrastructure is not yet geared for this daunting challenge. Neither there are postgraduate training programs for CNSs nor is there a career ladder that provides financial or professional rewards for expertise and increased responsibility and accountability.

This article sheds light on a successful model that should be adopted at a national level in order to advance nursing in Saudi Arabia–a model based on the partnership between two certified CNSs and the colorectal surgeons at a tertiary care center, who work toward a shared goal, patient-centered care. The roles are complementary and are clearly defined and outlined with strong executive support. The relationship is not vertical but horizontal, allowing both parties to provide an integral part in the decision-making process, each within his/her domain of practice. The model is supported by a clinical grading ladder with professional and financial rewards for an increased level of expertise, responsibility and accountability.

In our experience, demonstration by the colorectal CNSs of their knowledge, expertise and skill has gained the respect and trust of patients, nurses, nursing executives and physicians alike. This mutual respect and trust has had a positive impact on interdisciplinary communication and collaborative practice, enabling the provision of patient-centered care. The success of this nurse–physician partnership can be attributed to the willingness of the CNSs and physicians to accept the importance of the others’ role and the contribution each makes to patient care. Partnering on all aspects of the four domains of the NC’s role is integral to our team approach to the provision of specialist care and in developing specialist services and educational programs within the country.

The development of CNS and NC roles in Saudi Arabia will be important to nursing as a profession. Specialist nurses are heavily involved in clinical research and in the utilization of evidence-based practice at the bedside, in setting standards locally and nationally, and in developing and providing local and national education initiatives for patients, nurses, and physicians.7 This role cuts across both nursing and medical domains; in a country where health care is still dominated by the medical model, CNSs will need the support of both nursing executives and physicians.

Conclusion

Saudi Arabia lacks nurse specialists, their role is not well accepted in the medical community, and nurses wishing to develop themselves as CNSs are routinely considered coordinators following physicians’ orders. Nurse specialists are a necessity for vulnerable patient populations with specialized care requirements. It is important to develop such nursing roles, and to equip these nurses with the knowledge, skill and experience to match the needs of their patient population. Moreover, it is vital to their function to empower them with autonomy coupled with accountability in a collegial relationship with the physician. The success of the colorectal clinical nurse specialist–physician model is a testament to the validity of this conclusion.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Judy Moseley, Executive Chief of Nursing Affairs, and Donna Hilliard, Program Director, Nursing Development and Saudization, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh, for their encouragement, advice, and support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fulton JS, Baldwin K. An annotated bibliography reflecting CNS practice and outcomes. Clin Nurse Spec. 2004;18:21–39. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laurant M, Harmsen M, Wollersheim H, Grol R, Faber M, Sibbald B. The impact of nonphysician clinicians: Do they improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of health care services? Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66:36S–89. doi: 10.1177/1077558709346277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health Saudi Arabia. Statistics Year Book 2008, chap. 2. Health Resources. 2008:125. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodward VA, Webb C, Prowse M. Nurse consultants: Their characteristics and achievements. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:845–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Currie L, Watterson L. Investigating the role and impact of expert nurses. Br J Nurs. 2009;18:816, 818–24. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2009.18.13.43218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daly WM, Carnwell R. Nursing roles and levels of practice: A framework for differentiating between elementary, specialist and advancing nursing practice. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:158–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Association of Colleges of Nursing A. AACN Statement of Support for Clinical Nurse Specialists. 2006. [Last accessed on 2010 Aug 20]. Available from: http://www.aacn.nche.edu/publication/pdf/CNS.pdf.

- 8.Durgahee T. Higher level practice: Degree of specialist practice? Nurse Educ Today. 2003;23:191–201. doi: 10.1016/s0260-6917(02)00186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bousfield C. A phenomenological investigation into the role of the clinical nurse specialist. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:245–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health; Health D, editor. London: Crown; 1999. [Last accessed on 2010 Aug 8]. Nurse, midwife and health visitor consultants: Establishing posts and making appointments. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4012227.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manley K, Hardy S, Titchen A, Garbett R, McCormack B. Changing patients’ worlds through nursing practice expertise: Exploring nursing practice expertise through emancipatory action research and fourth generation evaluation. London: Royal College of Nursing; 2005. [Last accessed on 2010 Aug 18]. Report No.: 1998–2004. Available from: http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/78647/002512.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savage LS, Grap MJ. Telephone monitoring after early discharge for cardiac surgery patients. Am J Crit Care. 1999;8:154–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryan S, Hassell AB, Lewis M, Farrell A. Impact of a rheumatology expert nurse on the wellbeing of patients attending a drug monitoring clinic. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53:277–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill J, Thorpe R, Bird H. Outcomes for patients with RA: A rheumatology nurse practitioner clinic compared to standard outpatient care. Musculoskeletal Care. 2003;1:5–20. doi: 10.1002/msc.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keefe A. Development of nurse-led clinics in genitourinary medicine. Nurse Prescr. 2008;6:246–50. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry-Woodford Z. A clinical audit of the ileoanal pouch service at St Mark’s Hospital. Gastrointest Nurs. 2008;6:36–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill J, Lewis M, Bird H. Do OA patients gain additional benefit from care from a clinical nurse specialist?--A randomized clinical trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:658–64. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardie H, Leary A. Value to patients of a breast cancer clinical nurse specialist. Nurs Stand. 2010;24:42–7. doi: 10.7748/ns2010.04.24.34.42.c7720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leary A, Oliver S. Clinical nurse specialists: Adding value to care: An executive summary. London: Royal College of Nursing; 2010. [Last accessed on 2010 Aug 18]. Available from: http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/317780/003598.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Disch J, Walton M, Barnsteiner J. The role of the clinical nurse specialist in creating a healthy work environment. AACN Clin Issues. 2001;12:345–55. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200108000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denver EA, Barnard M, Woolfson RG, Earle KA. Management of uncontrolled hypertension in a nurse-led clinic compared with conventional care for patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2256–60. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.8.2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edge V. A lifelong journey. Nurs Stand. 2006;20:20–1. doi: 10.7748/ns.20.35.20.s28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blue L, Lang E, McMurray JJ, Davie AP, McDonagh TA, Murdoch DR, et al. Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. BMJ. 2001;323:715–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooten D, Youngblut JM, Brown L, Finkler SA, Neff DF, Madigan E. A randomized trial of nurse specialist home care for women with high-risk pregnancies: Outcomes and costs. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7:793–803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wheeler EC. The CNS’s impact on process and outcome of patients with total knee replacement. Clin Nurse Spec. 2000;14:159–69. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200007000-00008. quiz 170–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royal College of Nursing. Specialist nurses: Changing lives saving money. London: RCN; 2010. [Last accessed on 2010 Aug 8]. Report No.: 003 581 Available from: http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/302489/003581.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKenna H, Keeney S, Hasson F. Health care managers’ perspectives on new nursing and midwifery roles: Perceived impact on patient care and cost effectiveness. J Nurs Manag. 2009;17:627–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prevost SS. Clinical nurse specialist outcomes: Vision, voice, and value. Clin Nurse Spec. 2002;16:119–24. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewandowski W, Adamle K. Substantive areas of clinical nurse specialist practice: A comprehensive review of the literature. Clin Nurse Spec. 2009;23:73–90. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e31819971d0. quiz 91–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham IW. Consultant nurse-consultant physician: A new partnership for patient-centred care? J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1809–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leary A, Crouch H, Lezard A, Rawcliffe C, Boden L, Richardson A. Dimensions of clinical nurse specialist work in the UK. Nurs Stand. 2008;23:40–4. doi: 10.7748/ns2008.12.23.15.40.c6737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tumulty G. Professional development of nursing in Saudi Arabia. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33:285–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Littlewood J, Yousuf S. Primary health care in Saudi Arabia: Applying global aspects of health for all, locally. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:675–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Omar BA. Knowledge, attitudes and intention of high school students towards the nursing profession in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:150–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mebrouk J. Perception of nursing care: Views of Saudi Arabian female nurses. Contemp Nurse. 2008;28:149–61. doi: 10.5172/conu.673.28.1-2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller-Rosser K, Chapman Y, Francis K. Historical, cultural, and contemporary influences on the status of women in nursing in Saudi Arabia. Online J Issues Nurs. 2006;11:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frampton SB, Wahl C, Cappiello G. Putting patients first: Partnering with patients’ families. Am J Nurs. 2010;110:53–6. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000383936.68462.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collett A, Kent W, Swain S. The role of a telephone helpline in provision of patient information. Nurs Stand. 2006;20:41–4. doi: 10.7748/ns2006.04.20.32.41.c4125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baggs JG. Collaboration between nurses and physicians. J Nurs Scholarsh. 1988;20:145–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1988.tb00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salvage J, Smith R. Doctors and nurses: Doing it differently. BMJ. 2000;320:1019–20. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7241.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Storch JL, Kenny N. Shared moral work of nurses and physicians. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14:478–91. doi: 10.1177/0969733007077882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fagin L, Garelick A. The doctor-nurse relationship. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2004;10:277–86. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Norton C, Kamm MA. Specialist nurses in gastroenterology. J R Soc Med. 2002;95:331–5. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.95.7.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baggs JG. Nurse-physician collaboration in intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:641–2. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254039.89589.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benner P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Menlo Park, California: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fatani HH, Mira SA, El-Zubier AG. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in rural Saudi Arabia. Diabetes Care. 1987;10:180–3. doi: 10.2337/diacare.10.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Nozha MM, Al-Maatouq MA, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Harthi SS, Arafah MR, Khalil MZ, et al. Diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1603–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saudi Cancer Registry. Cancer Incidence Report 2006. Riyadh: Ministry of Health, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center; 2006. [Last accessed on 2010 Sep 19]. Available from: http://www.scr.org.sa/ [Google Scholar]

- 49.KFS Hand RC Tumor Registry. Annual report 1980. Riyadh: King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center; 1980. [Google Scholar]