Abstract

Plasma lipid levels are heritable quantitative risk factors and therapeutic targets for cardiovascular disease. Plasma lipids have been a model for translating genetic observations across the allele frequency spectrum to unique biological and therapeutic insights. Most large studies to date predominately comprised of individuals of European ancestry. This review focuses on contemporary evidence from 2016–2017 looking at the effect of genetic variants on plasma lipid levels across the allele frequency spectrum with incrementally larger sample sizes and the contribution of non-European ancestry studies to the genetic aetiology of plasma lipid levels. To date, over 250 loci have been associated with plasma lipid levels and several of these loci have additional evidence of association with rare coding variants providing evidence for the causal genes at each locus.

Introduction

Plasma lipid levels including low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), total cholesterol (TC), and triglycerides (TG) are quantitative risk factors for cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in the United States and now worldwide[1,2]. Plasma lipids are strongly heritable – estimated to be approximately 60%[3]. Furthermore, lipid measurements are used in routine clinical practice for risk prediction and therapeutic titration[4,5], and are regularly collected within epidemiological cohorts[6–8] making them desirable phenotypes for genetic analyses with the goals of 1) gaining biological insights and determining clinical risk for plasma lipids and cardiovascular disease, and 2) serving as a model for complex trait genetics since both polygenic and monogenic causes influence plasma lipid levels, with robust evidence of association.

Numerous studies of the effect of genetic variants on plasma lipid levels have identified monogenic (single gene of large effect) and polygenic (multiple genes with small effects) contributors. Initial studies focused on familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by elevated LDL-C and markedly increased coronary heart disease risk (CHD). In the 1970s, Brown and Goldstein described FH as due to dysfunction of the LDL receptor (LDLR) and concomitant over-activity of HMG-CoA reductase[9,10]. Such observations were critical to 1) establishing the causal link between LDL-C and atherosclerosis, and 2) establishing HMG-CoA reductase as a therapeutic target (now the target of statins).

Over the last 50 years, additional disruptive mutations with large effects on lipid levels have been identified[11,12] as well as over 250 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been shown to associate with plasma lipids in the population[13] using genome-wide association studies (GWAS), mostly in individuals of European ancestry. This review will focus on the incremental contemporary evidence from 1) increasingly larger sample sizes, 2) inclusion of non-European ancestry participants, and 3) population-based analyses of aggregates of rare, coding variation.

Genetic variation detected through single variant testing

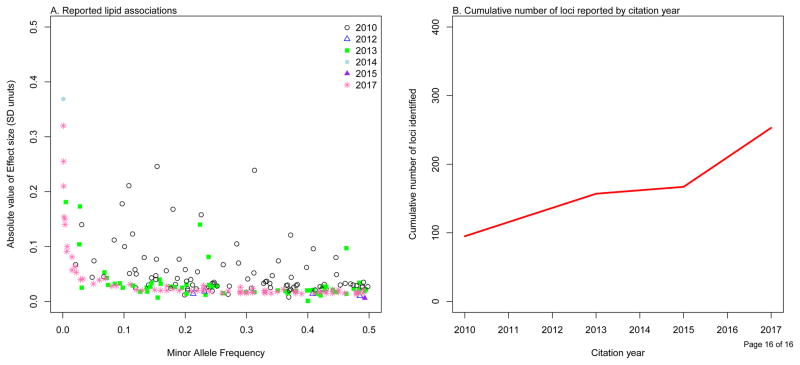

Multiple studies of common SNPs (allele frequency > ~1%) have focused on analyzing individual SNPs across the genome for association with plasma lipids[7,8,13–19]. With successively larger GWAS sample sizes, we have been able to study assayed SNPs with lower minor allele frequencies (Figure 1A). Most recently, over 300,000 individuals have contributed to a meta-analysis using the ‘exome array’ platform of over 242,000 variants, with roughly 87% of the variants being protein-altering coding variants[13]. With this latest GWAS, 250 loci associated with plasma lipids have been identified (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Reported lipid associations through genome-wide scans.

(A). Effect size by minor allele frequency of 229 reported lipid associations using results from the GLGC exome chip (http://csg.sph.umich.edu/abecasis/public/lipids2017/). The reported lead trait was used for each of the reported SNPs with effect sizes in standard deviation units. Exome chip association results were not available for 21 reported SNPs; SNP proxies were used for 16 reported SNPs. (B). Cumulative number of loci detected (both novel and known) for plasma lipid levels by citation year.

An application of this data type include using genetic variants as instruments to determine the causality of epidemiological observations (i.e., Mendelian Randomization). This entails estimating the relationship between genetic variants that are associated with the risk factor of interest as well as the relationship between the same genetic variants and the outcome. For example, while observational epidemiological studies demonstrated a strong inverse correlation between HDL-C and CHD risk, Mendelian randomization demonstrated that this was not a causal relationship[20]. Mendelian randomization also showed that, similar to LDL-C, triglyceride rich lipoproteins (TRLs) are causally associated with CHD[21]. TRLs transport both cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood. In 2016, Helgadottir et al. found that a genetic risk score created for the non-HDL-C phenotype (Total cholesterol minus HDL-C) confers risk beyond that of LDL-C, suggesting that the cholesterol content of the TRLs may increase cardiovascular risk[22]. A key challenge is that, by definition, non-HDL-C is correlated with triglycerides (5 * (total cholesterol minus HDL-C minus LDL-C)). Variants that influence serum triglycerides were shown to influence cardiometabolic disease risk but with individually variable biological consequences. Liu et al. observed that TG-lowering alleles involved in hepatic production of TG-rich lipoproteins (TM6SF2 and PNPLA3) lead to increased liver fat, increased risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D), and reduced risk for CHD, while TG-lowering alleles involved in peripheral lipolysis (LPL and ANGPTL4) have no effect on liver fat but reduced risks for both T2D and CHD. These findings suggest that therapeutics targeting peripheral lipolysis may decrease risk for both T2D and CHD without steatosis, and moreover, that certain TRL pathways may lead to increased risk of T2D. TRL cholesterol content, or remnant cholesterol, has been shown to associate with incident CHD[23] but the model did not take into account the triglyceride content of TRLs. The relative contributions of both remnant cholesterol and remnant triglycerides on CHD is unknown. Discovering genetic markers influencing only remnant cholesterol or only remnant triglycerides may help disentangle these two components.

Contribution of non-European individuals

A key limitation of GWAS, including for plasma lipids, is that most have primarily consisted of individuals of European ancestry[24]. In 2012, Musurunu et al, found in a study of 25,000 individuals of European ancestry and 9,000 individuals of African ancestry evidence of allelic heterogeneity – while the loci tended to be the same, the SNPs identified were often distinct[25]. Recently, others studying body mass index (BMI)[26] and glycemic traits[27] have drawn similar conclusions. Notably, these differences have implications for polygenic risk score accuracy across diverse individuals. In 2017, Wang et al performed a study in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) of polygenic risk scores previously shown to be associated with lipoprotein subclasses[28]. While they were able to replicate the associations between the genetic risk score and lipoprotein subclasses with the European ancestry subjects, fewer associations replicated among non-European ancestry subjects, which could be due to allelic heterogeneity as they estimated over 95% power to detect the associations in the non-European samples.

On the other hand, analysis of non-European individuals can aide in prioritizing causal genes at GWAS signals. The association of multiple ancestry-specific protein-altering coding variants within the same gene is strongly supportive of that gene being causal as the effect of disrupting that gene in multiple ancestries leads to phenotypic changes. Secondly, if the same lead variant is associated with a trait in multiple ancestries it may indicate a causal variant. Lu et al. compared the associations from an exome array study of 47,532 East Asian individuals to that of 300,000 individuals of predominately (80%) European ancestry and found that at 38 previously implicated lipid loci, 24 had the same lead variants between ancestries while 14 loci showed evidence for allelic heterogeneity between ancestries[29]. They also found 16 genes with protein-altering variants in both East Asian and European ancestry individuals, indicating that since protein-altering variants are associated in multiple ancestries these are likely to be in the functional genes at the locus. Using MetaboChip array data on 54,000 non-European individuals including multiple ancestries (African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Asians, and American Indians), Zubair et al. was able to refine association signals for 16 out of 58 loci by identifying whether the previously associated lead SNP was in high linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the lead SNP from association analysis in African Americans (with shorter LD blocks) [30] indicating that they were tagging the same causal variant. Finally, non-European individuals can be useful in identifying novel loci. Three additional loci were identified in 47,532 East Asian individuals by Lu et al that were not previously implicated for plasma lipids[29].

Genetic variation detected through aggregation testing

While common genetic variation associated with fasting plasma lipids can be found through single variant association analyses using population-based samples, statistical power for individual rare genetic variants (minor allele frequency < 1%) is limited. Thus, rare genetic variants predicted to have similar impacts on protein sequence are aggregated by a functional unit, typically a gene. Further, rare variants cannot be comprehensively catalogued using existing array technology as arrays do not typically capture private mutations and require sequencing for discovery. As the costs of whole exome and whole genome sequencing continue to decrease, scalable query and discovery of rare genetic variants associated with plasma lipids in the population is now feasible.

Genes that have multiple variants with association evidence across the allelic spectrum of variation (i.e., nearby common SNPs with small effects to rare disruptive coding variants with larger effects) have strong support for causality. In the early-2000s, families with autosomal dominant familial hypercholesterolemia without characteristic mutations, were shown to carry missense mutations (later characterized to be gain-of-function) in proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) through gene mapping[11]. Subsequently, low-frequency disruptive coding variants in PCSK9 were demonstrated to associate with lower plasma LDL-C[31] and consequently reduced risk for CHD[32,33] in the population. Additionally, a common non-coding variant near PCSK9 has also been shown to alter LDL-C[15]. Such observations have spurred the development of PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies, which have been shown to both reduce LDL-C and CHD risk in randomized controlled clinical trials[34].

Khera et al found that carriers of rare disruptive variants in the lipoprotein lipase (LPL) gene had 20 mg/dl higher levels of triglycerides and a 1.8-fold increased risk of CHD compared to non-carriers, and that carriers of common variants analogously had a 1.5-fold increased risk of CHD per 1-standard deviation increase in triglyceride levels[35]. In another study, Dewey et al. found evidence for association between rare variants in CD36 and HDL-C in individuals of European ancestry[36]. Previously a distinct low frequency (3% carrier rate) variant in CD36 was shown to associate with HDL-C in African Americans[37,38].

Rare genetic variation can provide valuable evidence for prioritizing potential drug targets. In addition to the PCSK9 example discussed above, disruptive mutations in APOC3, encoding apolipoprotein C-III (apoC-III), associate with reduced serum triglycerides[12] and subsequently with reduced CHD risk[39–41]. This has led to inhibitors of apoC-III currently under development[42,43] and have an FDA Orphan Drug Designation to manage refractory hypertriglyceridemia in the setting of familial chylomicronemia syndrome.

More recently, Dewey et al. studied over 39,000 participants, mostly of European ancestry, with lipid levels derived from electronic health records (EHR) and exome sequencing[36]. They found six out of nine genes that are therapeutic targets for lipid-lowering medications have loss-of-function variants that were at least nominally associated with changes in lipid levels, indicating use of EHR is an approach that can be used to discover new drug targets. Furthermore, they identified a new gene, glucose-6 phosphatase catalytic subunits (G6PC), associated with increased triglyceride levels.

Genetics has also been used to evaluate therapeutics already in development. Ezetimibe is a non-statin lipid-lowering medicine that lowers LDL-C, but it was previously unclear whether it also lowered CHD risk. Stitziel et al identified individuals with a loss-of-function mutation in NPC1L1 (1 carrier in 650 individuals), the target of ezetimibe[44]. These individuals had lower LDL-C concentrations and lower risk for CHD. Analogously, in a subsequently reported clinical trial, individuals receiving ezetimibe had a lower risk of CHD[45]. Given prior epidemiological inverse correlations between HDL-C and CHD, several drugs inhibiting CETP to raise HDL-C have been evaluated for their ability to lower CHD risk, largely all with no associations observed. Nomura et al studied individuals with loss-of-function mutations in CETP; these individuals had high HDL-C, lower TG, lower LDL-C, and, surprisingly, a lower risk of CHD[46]. Another study found that that CETP variants that increased HDL-C, but did not lower LDL-C, did not have significantly reduced risk of CHD in over 150,000 Chinese individuals[47]. A recent trial of anacetrapib, a CETP inhibitor, found that individuals receiving on anacetrapib had lower LDL-C, unlike prior CETP inhibitors; such individuals had a lower risk of CHD and this was proportional to the degree of LDL-C lowering[48]. This suggests that increasing HDL-C without lowering LDL-C does not reduce risk of CHD and may provide evidence for why CETP inhibitors have largely failed to show a reduction in CHD risk.

Conclusions

Over the last 10 years, population genetic analyses of plasma lipids have yielded over 250 loci identified through single SNP analyses as well as aggregates of rare variants within genes. These discoveries have permitted novel biological and therapeutic insights.

Most of large genetic studies to date have studied individuals of European ancestry. Non-European individuals have the ability to extend our findings by (1). Providing a rich set of genetic variation that has yet to be tested, and (2). Prioritizing causal genes in known regions associated with plasma lipid levels. Furthermore, as a clinical potential of genetic analysis is risk prediction, ongoing analyses in diverse ancestries will be critical for accurate application across diverse individuals[49]. Therefore, strategies to utilize genetic risk for precision medicine will need to be expanded and incorporate diverse samples.

Of note, large bulk of genomic variation has not been assessed for lipids or other complex traits – structural variation and rare, non-coding variation. Whole genome sequencing is now feasible at large-scale and ongoing studies will permit querying such variation. However, current limitations with structural variant discovery from short reads and functional interpretation of rare non-coding variation for analysis need to be addressed to realize some of the incremental value of whole genome sequence analysis.

Acknowledgments

Gina M Peloso is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health award K01HL125751. Pradeep Natarajan is supported by the American Heart Association Award 17SDG33680041.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kathiresan S, Manning AK, Demissie S, D’Agostino RB, Surti A, Guiducci C, Gianniny L, Burtt NP, Melander O, Orho-Melander M, et al. A genome-wide association study for blood lipid phenotypes in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emerging Risk Factors Consortium. Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, Perry P, Kaptoge S, Ray KK, Thompson A, Wood AM, Lewington S, Sattar N, et al. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA. 2009;302:1993–2000. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, Goldberg AC, Gordon D, Levy D, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S1–S45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peloso GM, Auer PL, Bis JC, Voorman A, Morrison AC, Stitziel NO, Brody JA, Khetarpal SA, Crosby JR, Fornage M, et al. Association of low-frequency and rare coding-sequence variants with blood lipids and coronary heart disease in 56,000 whites and blacks. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surakka I, Horikoshi M, Magi R, Sarin AP, Mahajan A, Lagou V, Marullo L, Ferreira T, Miraglio B, Timonen S, et al. The impact of low-frequency and rare variants on lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2015;47:589–597. doi: 10.1038/ng.3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global Lipids Genetics Consortium. Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, Peloso GM, Gustafsson S, Kanoni S, Ganna A, Chen J, Buchkovich ML, et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1274–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Expression of the familial hypercholesterolemia gene in heterozygotes: mechanism for a dominant disorder in man. Science. 1974;185:61–63. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4145.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Familial hypercholesterolemia: defective binding of lipoproteins to cultured fibroblasts associated with impaired regulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:788–792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.3.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabes JP, Allard D, Ouguerram K, Devillers M, Cruaud C, Benjannet S, Wickham L, Erlich D, et al. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat Genet. 2003;34:154–156. doi: 10.1038/ng1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollin TI, Damcott CM, Shen H, Ott SH, Shelton J, Horenstein RB, Post W, McLenithan JC, Bielak LF, Peyser PA, et al. A null mutation in human APOC3 confers a favorable plasma lipid profile and apparent cardioprotection. Science. 2008;322:1702–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.1161524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **13.Liu DJ, Peloso GM, Yu H, Butterworth AS, Wang X, Mahajan A, Saleheen D, Emdin C, Alam D, Alves AC, et al. Exome-wide association study of plasma lipids in >300,000 individuals. Nat Genet. 2017 doi: 10.1038/ng.3977. This is the most recent large-scale association analysis for plasma lipids and brings the number of associated loci to 250. It also performs functional follow-up and uses identified variants to make insights on clinical translation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kathiresan S, Melander O, Guiducci C, Surti A, Burtt NP, Rieder MJ, Cooper GM, Roos C, Voight BF, Havulinna AS, et al. Six new loci associated with blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides in humans. Nat Genet. 2008;40:189–197. doi: 10.1038/ng.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teslovich TM, Musunuru K, Smith AV, Edmondson AC, Stylianou IM, Koseki M, Pirruccello JP, Ripatti S, Chasman DI, Willer CJ, et al. Biological, clinical and population relevance of 95 loci for blood lipids. Nature. 2010;466:707–713. doi: 10.1038/nature09270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asselbergs FW, Guo Y, van Iperen EP, Sivapalaratnam S, Tragante V, Lanktree MB, Lange LA, Almoguera B, Appelman YE, Barnard J, et al. Large-scale gene-centric meta-analysis across 32 studies identifies multiple lipid loci. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:823–838. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albrechtsen A, Grarup N, Li Y, Sparso T, Tian G, Cao H, Jiang T, Kim SY, Korneliussen T, Li Q, et al. Exome sequencing-driven discovery of coding polymorphisms associated with common metabolic phenotypes. Diabetologia. 2013;56:298–310. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2756-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peloso GM, Auer PL, Bis JC, Voorman A, Morrison AC, Stitziel NO, Brody JA, Khetarpal SA, Crosby JR, Fornage M, et al. Association of Low-Frequency and Rare Coding-Sequence Variants with Blood Lipids and Coronary Heart Disease in 56,000 Whites and Blacks. American journal of human genetics. 2014;94:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang CS, Zhang H, Cheung CY, Xu M, Ho JC, Zhou W, Cherny SS, Zhang Y, Holmen O, Au KW, et al. Exome-wide association analysis reveals novel coding sequence variants associated with lipid traits in Chinese. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10206. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M, Frikke-Schmidt R, Barbalic M, Jensen MK, Hindy G, Holm H, Ding EL, Johnson T, et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2012;380:572–580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Do R, Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, Gao C, Peloso GM, Gustafsson S, Kanoni S, Ganna A, Chen J, et al. Common variants associated with plasma triglycerides and risk for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1345–1352. doi: 10.1038/ng.2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *22.Helgadottir A, Gretarsdottir S, Thorleifsson G, Hjartarson E, Sigurdsson A, Magnusdottir A, Jonasdottir A, Kristjansson H, Sulem P, Oddsson A, et al. Variants with large effects on blood lipids and the role of cholesterol and triglycerides in coronary disease. Nat Genet. 2016;48:634–639. doi: 10.1038/ng.3561. Large-scale study performed in Icelanders shows large effect variants associated with plasma lipids using whole-genome sequencing data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joshi PH, Khokhar AA, Massaro JM, Lirette ST, Griswold ME, Martin SS, Blaha MJ, Kulkarni KR, Correa A, D’Agostino RB, Sr, et al. Remnant Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Incident Coronary Heart Disease: The Jackson Heart and Framingham Offspring Cohort Studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016:5. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popejoy AB, Fullerton SM. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature. 2016;538:161–164. doi: 10.1038/538161a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Musunuru K, Romaine SP, Lettre G, Wilson JG, Volcik KA, Tsai MY, Taylor HA, Jr, Schreiner PJ, Rotter JI, Rich SS, et al. Multi-ethnic analysis of lipid-associated loci: the NHLBI CARe project. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandez-Rhodes L, Gong J, Haessler J, Franceschini N, Graff M, Nishimura KK, Wang Y, Highland HM, Yoneyama S, Bush WS, et al. Trans-ethnic fine-mapping of genetic loci for body mass index in the diverse ancestral populations of the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) Study reveals evidence for multiple signals at established loci. Hum Genet. 2017;136:771–800. doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1787-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bien SA, Pankow JS, Haessler J, Lu YN, Pankratz N, Rohde RR, Tamuno A, Carlson CS, Schumacher FR, Buzkova P, et al. Transethnic insight into the genetics of glycaemic traits: fine-mapping results from the Population Architecture using Genomics and Epidemiology (PAGE) consortium. Diabetologia. 2017;60:2384–2398. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4405-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Manichukal A, Goff DC, Jr, Mora S, Ordovas JM, Pajewski NM, Post WS, Rotter JI, Sale MM, Santorico SA, et al. Genetic associations with lipoprotein subfraction measures differ by ethnicity in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) Hum Genet. 2017;136:715–726. doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1782-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *29.Lu X, Peloso GM, Liu DJ, Wu Y, Zhang H, Zhou W, Li J, Tang CS, Dorajoo R, Li H, et al. Exome chip meta-analysis identifies novel loci and East Asian-specific coding variants that contribute to lipid levels and coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2017 doi: 10.1038/ng.3978. Large-scale association study in East Asian individuals that identified novel loci and compares protein-coding variants in both East Asians and Europeans using the exome-array. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *30.Zubair N, Graff M, Luis Ambite J, Bush WS, Kichaev G, Lu Y, Manichaikul A, Sheu WH, Absher D, Assimes TL, et al. Fine-mapping of lipid regions in global populations discovers ethnic-specific signals and refines previously identified lipid loci. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25:5500–5512. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw358. This study provides a framework for fine-mapping previously identified lipid loci using multiple ancestries. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J, Pertsemlidis A, Kotowski IK, Graham R, Garcia CK, Hobbs HH. Low LDL cholesterol in individuals of African descent resulting from frequent nonsense mutations in PCSK9. Nat Genet. 2005;37:161–165. doi: 10.1038/ng1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH, Jr, Hobbs HH. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1264–1272. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kathiresan S. A PCSK9 missense variant associated with a reduced risk of early-onset myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2299–2300. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0707445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, Kuder JF, Wang H, Liu T, Wasserman SM, et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khera AV, Won HH, Peloso GM, O’Dushlaine C, Liu D, Stitziel NO, Natarajan P, Nomura A, Emdin CA, Gupta N, et al. Association of Rare and Common Variation in the Lipoprotein Lipase Gene With Coronary Artery Disease. JAMA. 2017;317:937–946. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **36.Dewey FE, Murray MF, Overton JD, Habegger L, Leader JB, Fetterolf SN, O’Dushlaine C, Van Hout CV, Staples J, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, et al. Distribution and clinical impact of functional variants in 50,726 whole-exome sequences from the DiscovEHR study. Science. 2016:354. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6814. Using lipid levels from electronic health records with whole-exome sequencing to confirm genes that are drug targets and to identify new variants associated with plasma lipids. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coram MA, Duan Q, Hoffmann TJ, Thornton T, Knowles JW, Johnson NA, Ochs-Balcom HM, Donlon TA, Martin LW, Eaton CB, et al. Genome-wide characterization of shared and distinct genetic components that influence blood lipid levels in ethnically diverse human populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92:904–916. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elbers CC, Guo Y, Tragante V, van Iperen EP, Lanktree MB, Castillo BA, Chen F, Yanek LR, Wojczynski MK, Li YR, et al. Gene-centric meta-analysis of lipid traits in African, East Asian and Hispanic populations. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50198. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jorgensen AB, Frikke-Schmidt R, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3 and risk of ischemic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:32–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.TG and HDL Working Group of the Exome Sequencing Project, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Crosby J, Peloso GM, Auer PL, Crosslin DR, Stitziel NO, Lange LA, Lu Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in APOC3, triglycerides, and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:22–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Natarajan P, Kohli P, Baber U, Nguyen KD, Sartori S, Reilly DF, Mehran R, Muntendam P, Fuster V, Rader DJ, et al. Association of APOC3 Loss-of-Function Mutations With Plasma Lipids and Subclinical Atherosclerosis: The Multi-Ethnic BioImage Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2053–2055. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaudet D, Alexander VJ, Baker BF, Brisson D, Tremblay K, Singleton W, Geary RS, Hughes SG, Viney NJ, Graham MJ, et al. Antisense Inhibition of Apolipoprotein C-III in Patients with Hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:438–447. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graham MJ, Lee RG, Bell TA, 3rd, Fu W, Mullick AE, Alexander VJ, Singleton W, Viney N, Geary R, Su J, et al. Antisense Oligonucleotide Inhibition of Apolipoprotein C-III Reduces Plasma Triglycerides in Rodents, Nonhuman Primates, and Humans. Circ Res. 2013;112:1479–1490. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium Investigators. Stitziel NO, Won HH, Morrison AC, Peloso GM, Do R, Lange LA, Fontanillas P, Gupta N, Duga S, et al. Inactivating mutations in NPC1L1 and protection from coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2072–2082. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, Darius H, Lewis BS, Ophuis TO, Jukema JW, et al. Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387–2397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1410489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nomura A, Won HH, Khera AV, Takeuchi F, Ito K, McCarthy S, Emdin CA, Klarin D, Natarajan P, Zekavat SM, et al. Protein-Truncating Variants at the Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein Gene and Risk for Coronary Heart Disease. Circ Res. 2017;121:81–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Millwood IY, Bennett DA, Holmes MV, Boxall R, Guo Y, Bian Z, Yang L, Sansome S, Chen Y, Du H, et al. Association of CETP Gene Variants With Risk for Vascular and Nonvascular Diseases Among Chinese Adults. JAMA Cardiol. 2017 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.HPS3/TIMI55–REVEAL Collaborative Group. Bowman L, Hopewell JC, Chen F, Wallendszus K, Stevens W, Collins R, Wiviott SD, Cannon CP, Braunwald E, et al. Effects of Anacetrapib in Patients with Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1217–1227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin AR, Gignoux CR, Walters RK, Wojcik GL, Neale BM, Gravel S, Daly MJ, Bustamante CD, Kenny EE. Human Demographic History Impacts Genetic Risk Prediction across Diverse Populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100:635–649. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]