Abstract

Studies in skeletal muscle cell cultures suggest that the cortical actin cytoskeleton is a major requirement for insulin-stimulated glucose transport, implicating the β-actin isoform, which in many cell types is the main actin isoform. However, it is not clear that β-actin plays such a role in mature skeletal muscle. Neither dependency of glucose transport on β-actin nor actin reorganization upon glucose transport have been tested in mature muscle. To investigate the role of β-actin in fully differentiated muscle, we performed a detailed characterization of wild type and muscle-specific β-actin knockout (KO) mice. The effects of the β-actin KO were subtle; however, we confirmed the previously reported decline in running performance of β-actin KO mice compared with wild type during repeated maximal running tests. We also found insulin-stimulated glucose transport into incubated muscles reduced in soleus but not in extensor digitorum longus muscle of young adult mice. Contraction-stimulated glucose transport trended toward the same pattern, but the glucose transport phenotype disappeared in soleus muscles from mature adult mice. No genotype-related differences were found in body composition or glucose tolerance or by indirect calorimetry measurements. To evaluate β-actin mobility in mature muscle, we electroporated green fluorescent protein (GFP)-β-actin into flexor digitorum brevis muscle fibers and measured fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. GFP-β-actin showed limited unstimulated mobility and no changes after insulin stimulation. In conclusion, β-actin is not required for glucose transport regulation in mature mouse muscle under the majority of the tested conditions. Thus, our work reveals fundamental differences in the role of the cortical β-actin cytoskeleton in mature muscle compared with cell culture.

Keywords: actin cytoskeleton, β-actin, glucose transport, insulin, skeletal muscle

INTRODUCTION

In muscle and fat cells, the dynamic insulin-stimulated reorganization of the cortical actin cytoskeleton is a well-described crucial step in the insulin-stimulated translocation of vesicles containing glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) to facilitate glucose transport (6, 9). The mechanistic involvement of actin remodeling in GLUT4 translocation has been proposed at multiple steps, including vesicle tethering, movement, and fusion, in addition to localization of signaling proteins (6, 9). A disturbed regulation of the actin cytoskeleton may furthermore be a unifying theme underlying the reduced insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation in muscle cells made insulin resistant by various methods (27, 77). Accordingly, muscle insulin resistance correlates with changes in actin regulating signaling by proteins such as Rac1, PAK1, and ROCK1 and/or with altered actin morphology in a number of transgenic mouse models, in cell studies (18, 68, 69, 78, 79, 81, 84), and in type 2 diabetic humans (12, 68). The inhibition of the PtsIns3 phosphate-5-kinase PIKFyve, suggested to regulate actin morphology and GLUT4 translocation in cell culture (63), also reduces insulin- and contraction-stimulated glucose transport when inhibited in mature rodent muscle (25, 36). Furthermore, pharmacological depolymerization of the actin cytoskeleton by latrunculin B reduces insulin- and contraction-stimulated glucose transport into mouse muscles (7, 69, 70). Finally, a study in isolated mature feline cardiomyocytes overexpressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged β-actin used fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) imaging to conclude that the mobility of β-actin is increased following insulin stimulation (1). Taken together, these studies suggest that the requirement and function for actin is conserved between muscle cell culture and fully differentiated skeletal muscle. However, global disruption of the actin cytoskeleton using latrunculin B is a very crude tool to investigate the involvement of actin in glucose transport regulation and cannot establish the exact actin isoform involved. No studies, to our knowledge, have investigated isoform-specific actin dynamics in fully differentiated skeletal muscle.

The mammalian actin family of proteins encompasses four muscle-specific isoforms (αsmooth, γsmooth, αcardiac and αskeletal) and the two ubiquitously expressed cytoplasmic β- and γ-actin isoforms (8, 31). The skeletal muscle actin pool is dominated by the highly expressed αskeletal isoform that forms the thin filaments of the contractile apparatus compared with much lower expression of the cytoplasmic β- and γ-actins. The latter two actin isoforms are 99% homologous, differing by only 4 amino acids in their NH2 termini. However, although isolated β- and γ-actin can produce hybrid actin filaments in vitro (5, 41), suggesting that they may substitute for one another, the in vivo functions of β- and γ-actin are likely nonredundant, since 1) evidence suggests that β- and γ-actin localize to distinct compartments and form distinct actin structures within various cell types (8, 31), and 2) the muscle-specific knockout (KO) of either isoform produces a clear phenotype (57, 65). From the literature, most evidence in different cell types, including the muscle cell lines C2 myoblasts and L6 myoblasts and myotubes, points toward β-actin being the main constituent of the cortical actin cytoskeleton previously linked to GLUT4 translocation (22, 23, 30, 35, 64, 77). To directly investigate whether skeletal muscle β-actin regulates whole body metabolism and specifically muscle glucose transport in mice, we obtained and compared in vivo and ex vivo metabolic parameters in wild-type and muscle-specific β-actin KO mice.

METHODS

Animals.

The β-actin floxed mice were a kind gift from James M. Ervasti (Dept. of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, and Biophysics, Univ., of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) (54). The skeletal muscle-specific KO mice were littermates from breeding of hemizygous human α-skeletal actin (HSA)-Cre and β-actinflox/flox mice (57). To control for the progressive myopathy that develops in the β-actin KO mice (57), a young adult (8–13 wk old) and mature adult (18–23 wk old) cohort of mice was investigated for each sex. The liver kinase B1 (LKB1) muscle-specific KO mice were generated as previously described (75). Results from male and female mice were pooled unless noted, since they showed comparable phenotypes. All mice used at the University of Copenhagen were housed according to the Danish experimental animal legislation, while the wild-type C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories) used for GFP-actin transfection and confocal microscopy in National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) were housed according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Likewise, all animal experiments were approved by the Danish National Animal Experimental Inspectorate or by the NIAMS Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Genotyping.

(Muscle 5–10 mg) was lysed overnight at 55°C in 100 µl of DirectPCR Lysis Reagent (Tail) (250-101-T, Nordic BioSite) with freshly added 0.2 mg/ml proteinase K (Roche Diagnostics). The lysate was centrifuged at 1,250 g for 5 min at room temperature, and supernatant was kept for DNA extraction. The released DNA was diluted fivefold in dilution buffer (10 mM TRIS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and incubated for 15 min at 95°C. Five microliters of this dilution was then amplified in a 25-μl SYBR Green polymerase chain reaction (PCR) containing 1× Quantitect SYBR Green Master Mix (Qiagen) and 200 nM of each primer (gDNA: TCCAGCACGTGGGTCTTAGAGG and CTGGCAGGTAGGCTCAGCAGGT, β-actin flox: TCTCAGCCACGCCCTTTCTCATA and TGGGAGAACGGCAGAAGAAAGA, liver kinase B1 (LKB1) flox: GGCATGGCCTCACAGGGACTT and CGGCAGTACCGGCATAACCAAG). The amplification was monitored in real time using the MX3005P real-time PCR machine (Stratagene). All reactions were performed in triplicates, and the mean CT was used for calculations. Flox abundance was calculated as 2^(CT Flox − CT gDNA) and normalized to the geometric average of the Cre-negative mice.

Immunoblotting.

Lysate protein concentrations were determined by using BSA standards (Pierce) and bicinchoninic acid assay reagents (Pierce). Total protein and phosphorylation levels of relevant proteins were determined by standard immunoblotting techniques, loading equal amounts of protein. The primary antibodies used were phospho- (p)-Akt Ser473 (9271S), p-Akt Thr308 (9275S), p-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) Thr172 (2535S), p-acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2 (ACC2) Ser212 (3661S), p-eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) Thr56 (2331S), p-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Thr180/Tyr182 (9211S), p- Unc-51-like autophagy-activating kinase 1 (ULK1) Ser555 (5859S), hexokinase II (2867S) (all from Cell Signaling Technology), Rac1 (05-389, Millipore), GLUT4 (Pierce), β-actin (AC-15, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), dystrophin (ab15277, Abcam), LKB1 (Ley37D/G6, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 1 (SERCA1; A-6, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and SERCA2 (F-1, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in TBS-Tween 20 (YBST) containing either 2% skimmed milk or 3% BSA and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody. The membranes were incubated in the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 45 min at room temperature and washed in TBST before visualization of the proteins (ChemiDoc MP Imaging System, Bio-Rad).

GFP-β-actin transfection and fiber isolation.

The p-EGFP-actin plasmid, encoding a fusion protein consisting of the red-shifted, human codon-optimized variant of EGFP and the gene encoding human cytoplasmic β-actin, was a kind gift from A. Klip (no. 6116-1, Clontech Laboratories). For transfections, mouse flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles were electroporated in vivo according to a previously described protocol (15), with a few modifications. Briefly, mice were given a subcutaneous injection of buprenorphine-HCl (0.05 mg/kg) as analgesic and anesthetized using 4% isoflurane. Ten microliters of 0.36 mg/ml hyaluronidase (H3884, Sigma) was injected through the skin at the heel into the footpad. After 1 h, 20 µl of 0.25 mg/ml p-EGFP-actin plasmid was injected in the same place. Six pulses of 20 ms were delivered at 1 Hz with the voltage amplitude adjusted to yield an electric field of ~75 V/cm using acupuncture needles (0.20 × 25 mm, Tai Chi, Lhasa OMS) connected to an ECM 830 BTX electroporator (BTX Harvard Apparatus). After 5–7 days, the animals were euthanized with CO2, and individual FDB fibers were isolated and cultured as described previously (44). After overnight culturing, fibers were kept in either the basal state or stimulated with 60 nM insulin for 30 min before imaging, unless otherwise stated.

GFP-β-actin transfection and antibody staining of cultured C2 myoblasts.

C2 myoblasts were kept in DMEM containing 25 mM glucose and 1 mM sodium pyruvate supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum. The cells were transfected with the pEGFP-actin plasmid by using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Promega) according to manufacturer’s protocol. For fixation, cells were incubated for 30 min in PBS containing 4% formaldehyde (FA) and 0.1% Triton X-100 followed by 5-min incubation in methanol. Cells where blocked in 1% goat serum and 2% BSA for 2 h, followed by 2-h incubation in anti-β-actin (AC-15, Ambion, Life Technologies). After three washes in PBS, the cells were incubated with anti-mouse Alexa 568 (Life Technologies) for 2 h; 0.04% saponin was used throughout blocking and antibody incubation.

Imaging and image analysis.

All imaging experiments were carried out in the Light Imaging Section of NIAMS (Bethesda, MD). Confocal images were collected using a ×63 1.4 NA oil immersion objective lens or a ×10 0.45 NA objective lens on a LSM 780 confocal microscope (Zeiss) driven by Zen 2011. For live-imaging, fibers were imaged in DMEM with 5% horse serum while kept at 5% CO2 in air and 37°C by a Pecon Laboratory-Tek S1 heat stage and an objective heater. For measurements of intensity accumulation, regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn around striations before insulin stimulation, and the signals in the ROIs were quantified relative to the total signal before and 10 min after insulin stimulation. For FRAP sequences, a ROI surrounding the cortical cytoskeleton in close proximity to the nucleus was manually drawn. Fibers were bleached for 10 iterations with 100% laser power and a ×63 objective, which yielded bleaching of 50–80% of the fluorescent molecules in the ROI. Some samples were fixed before imaging as a negative control by incubation with 2% FA in PBS for 20 min at room temperature.

Raw intensity values from FRAP sequences were exported and processed in the MATLAB plug-in easyFRAP (60). Images were exported in 8-bit TIF format, cropped, and linearly adjusted using Photoshop CC 2015 (Adobe).

MRI scan and weight.

Mice were weighed and MRI scanned (Echo MRi, Echo Medical Systems) to determine the body composition.

Glucose tolerance tests.

Prior to an intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT, 2 g/kg body wt d-glucose) mice were fasted for 5 h from 8:00 AM. Blood glucose concentration was measured in duplicate from the tail vein at time points 0, 20, 40, 60, and 90 min. A 50-µl blood sample was collected after 20 min for determination of the plasma insulin levels. Plasma insulin levels were determined using the Mouse Ultrasensitive Insulin ELISA kit (ALPCO Diagnostics).

Maximal running tests.

Mice were acclimated to the treadmill three times (11 min at 0.12 m/s, 60s at 0.38 m/s) (Treadmill TSE Systems) before the maximal running tests. The test started at 0.17 m/s for 300 s with 0% incline, followed by a continuing increase (0.15 m/s) in running speed every 60 s. The individual maximal running capacity was determined as the point where the mouse failed to run and stayed on the shocker for at least 5 s. All running tests were carried out as blinded experiments.

Indirect calorimetry.

Mice were singly housed and acclimated for 9 days and then singly housed in a 16-chamber indirect calorimetry system (PhenoMaster, TSE Systems) for 9 days. Baseline (72 h), fasting (24 h), refeed (72 h), and high-fat diet (48 h) conditions were included. Oxygen consumption rate (V̇o2, ml·h−1·kg−1), carbon dioxide production rate (V̇co2, ml·h−1·kg−1), respiratory exchange ratio (RER), total activity (beam breaks), food, and water intake were measured simultaneously for each mouse.

Muscle incubations.

Soleus and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles were excised from anesthetized mice (6 mg pentobarbital + Lidocaine/100 g body wt ip) and suspended in the incubation chambers (Multi Myograph System, Danish Myo-Technology) containing 30°C Krebs-Ringer-Henseleit (KRH) buffer with 8 mM mannitol and 2 mM pyruvate, as previously described (28). For insulin stimulation, muscles were preincubated for 30 min followed by 20 min of insulin stimulation. For submaximal insulin stimulation, soleus and EDL muscles were incubated with 1.8 and 3 nM insulin (Actrapid, Novo Nordisk), respectively, whereas maximal stimulation was 60 nM insulin for both muscles (40). For 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) experiments, the muscles were preincubated for 30 min and subsequently stimulated with 4 mM AICAR for 40 min. Contractions were induced by electrical stimulation every 15 s with 2-s trains of 0.2-ms pulses delivered at 100 Hz (~30 V) for 15 min. Passive stretch was induced by manually stretching the muscles to a tension of 100 mN for 5 min followed by adjustment to 130 mN for 10 min. Prior to contraction and passive stretch the muscles were pre-incubated for 45 min.

2-Deoxyglucose transport.

2-Deoxyglucose (2-DG) transport was measured for the last 10 min during all incubation protocols using 3H and 14C radioactive tracers, as described previously (28).

Muscle analyses.

Immediately after ex vivo incubation, the muscles were washed in ice-cold KRH medium and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue was homogenized for 1 min at 30 Hz using steel beads and a Tissue Lyser II bead-mill (Qiagen) in ice cold lysis B buffer (0.05 M Tris Base, pH 7.4, 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and EGTA, 0.05 M NaF, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and benzamidine (BZM), 0.5% protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340, Sigma-Aldrich), and 1% NP-40. Supernatants were collected after end-over-end rotation for 30 min at 4°C and centrifugation (18,327 g) for 20 min at 4°C.

Statistical analyses.

Results are presented as means ± SE. Statistical testing was performed using unpaired two-tailed t-test and one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Repeated-measures ANOVA was used for data with repeated sampling in the same animal, including the glucose tolerance tests as well as the indirect calorimetry data. Tukey’s post hoc test was used to identify differences if significant (P < 0.05) ANOVA effects were found. The statistical analyses were carried out in SigmaPlot v. 11.0.

RESULTS

Validation of the muscle-specific β-actin KO mouse model.

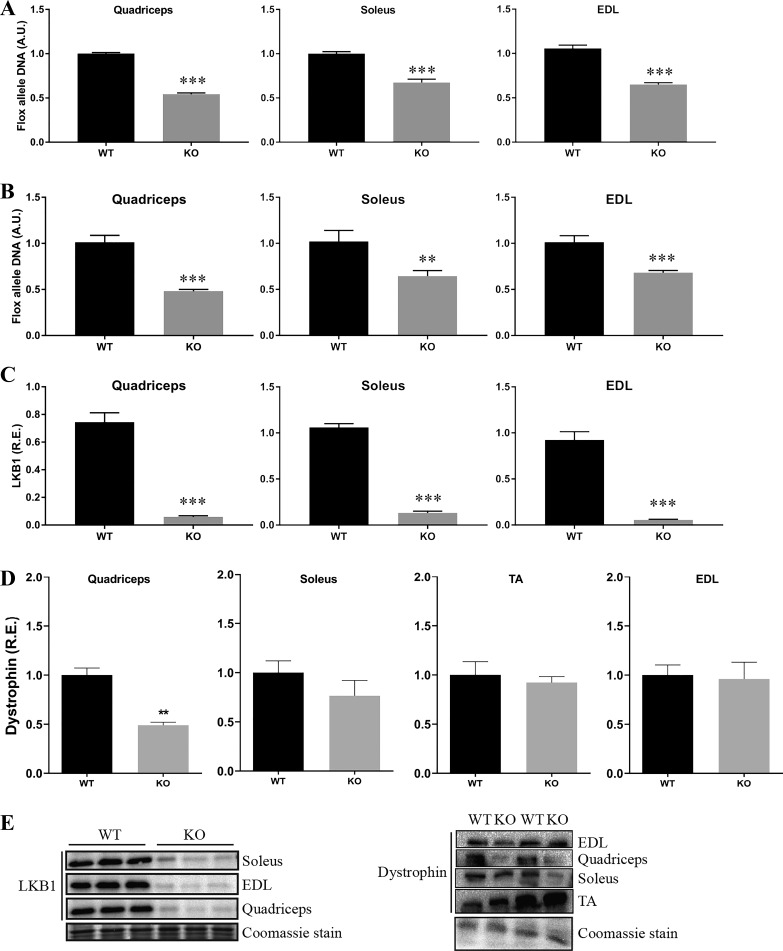

To study the role of β-actin in skeletal muscle glucose metabolism, we obtained and bred a previously characterized muscle-specific β-actin KO mouse model (57). This mouse model was originally reported to show an ~50% reduction in β-actin, with no compensatory changes in other actin isoforms (57). Myonuclei constitute approximately one-half of the total nuclei in adult mouse muscle (80); hence, the ~50% reduction of the floxed allele DNA in the quadriceps, soleus, and EDL muscles of the β-actin KO compared with wild-type mice verified the muscle-specific excision of the β-actin gene (Fig. 1A). Possibly due to the low expression of β-actin in myofibers vs. nonmuscle cells in skeletal muscle tissue (76), it was not possible to show decreased β-actin protein expression in the muscle-specific KO mice (data not shown). To verify that an ~50% reduction in the floxed allele would be expected from a complete muscle-specific KO, floxed allele excision was also measured in the muscle-specific LKB1 KO mice, together with protein expression of LKB1 in quadriceps, soleus, and EDL muscles. A similar ~50% reduction of the floxed allele was observed in the muscles of the LKB1 KO compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 1B), supporting that myonuclei constitute about one-half of the total nuclei in mouse skeletal muscle. LKB1 protein expression was almost completely abolished in the muscles of the LKB1 KO mice, showing that an ~50% reduction in floxed allele is consistent with a complete KO in myofibers (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, the previously reported reduction in dystrophin protein expression in the quadriceps muscles of the β-actin KO mice (57) was confirmed (Fig. 1D). The KO validation was limited to excision of the floxed allele and could not be confirmed by reduced β-actin protein expression. However, these data strongly support that efficient muscle-specific excision of β-actin in the KO mice had occurred as intended, but genotyping at protein level is not possible due to the low expression of β-actin in muscle fibers compared with nonmuscle cells.

Fig. 1.

Verification of the β-actin knockout (KO) genotype. A: quantification of the flox allele in quadriceps, soleus, and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles of wild-type (WT) and β-actin KO mice; n = 7–9 mice. All values are shown as means ± SE; ***P < 0.001. B: quantification of the flox allele in quadriceps, soleus, and EDL muscles of WT and liver kinase B1 (LKB1) KO mice; n = 4–6 mice. All values are shown as means ± SE; **P = 0.019, ***P ≤ 0.001. C: quantification of LKB1 protein expression in quadriceps, soleus, and EDL muscle lysates of WT and LKB1 KO mice; n = 5–7. All values are shown as means ± SE; ***P < 0.001. D: quantification of dystrophin protein expression in soleus, tibialis anterior (TA), quadriceps, and EDL muscle lysates of young adult WT and β-actin KO mice; n = 3–4. All values are shown as means ± SE; **P = 0.003. E: representative blots of quantified proteins in C and D. Coomassie staining is used as loading control. R.E., relative expression to WT; A.U., arbitrary units.

Young adult β-actin KO mice exhibit no overt in vivo phenotype except during repeated maximal running.

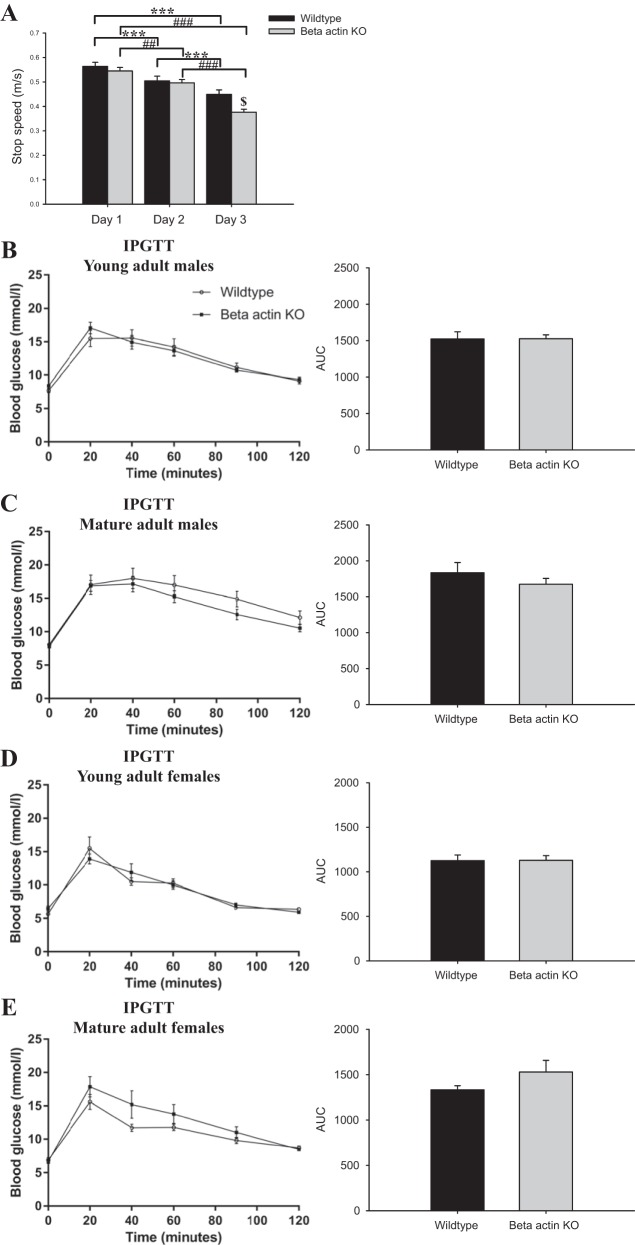

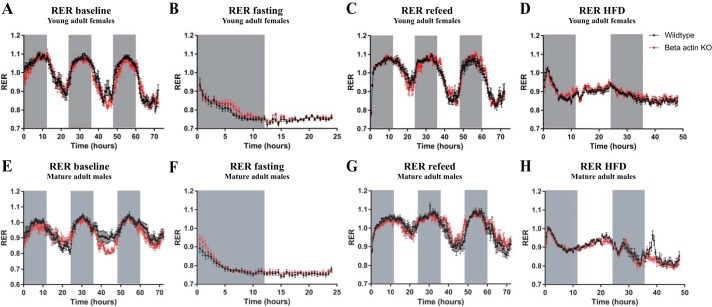

An extensive in vivo characterization of wild-type and muscle-specific β-actin KO mice was undertaken. As previously reported (57), a greater decline in maximal running performance was found in the β-actin KO mice compared with wild-type mice when repeatedly challenged with maximal running tests on consecutive days (Fig. 3A). No genotype-related differences were found for other in vivo parameters, including body composition, blood glucose, insulin levels (Table 1), substrate utilization (RER; Fig. 2), and glucose tolerance (Fig. 3, B–E). Neither did total activity, food, or water intake differ between the genotypes (data not shown). This shows that the muscle-specific β-actin KO mice are largely indistinguishable from their wild-type littermates at whole body level but do exhibit an impaired ability to recover from repeated exercise bouts.

Fig. 3.

No differences in glucose tolerance, but β-actin KO mice display decreased running performance. A: young adult female mice were subjected to a maximal running test each day for 3 days. Maximal running speed is denoted as stop speed (m/s; n = 8–10). Values\shown are means ± SE; ***P ≤ 0.001 within WT; ###P ≤ 0.001, ##P = 0.016 within KO; $P = 0.005, genotype difference. Young adult (B) and mature adult (C) male mice were fasted for 5 h and injected with 2 g/kg body wt d-glucose; n = 10. Blood glucose was measured after 0, 20, 40, 60, 90, and 120 min. Young adult (D) and mature adult (E) female mice were subjected to a similar protocol, n = 9–10. Area under the curve (AUC) of blood glucose is calculated from 1 to 120 min and shown as means ± SE. Young adult mice, 8–13 wk old; mature adult mice, 18–23 wk old.

Table 1.

No differences in selected in vivo characteristics

| Wild Type |

β-Actin KO |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young Adult (8–13 wk old) | Mature Adult (18–23 wk old) | Young Adult (8–13 wk old) | Mature Adult (18–23 wk old) | |

| Male | ||||

| Body weight, g | 27.3 ± 0.61 | 33.0 ± 0.98 | 27.0 ± 0.46 | 33.1 ± 0.49 |

| MRI - fat mass, g | 2.42 ± 0.16 | 4.13 ± 0.56 | 2.16 ± 0.15 | 3.75 ± 0.36 |

| MRI - lean mass, g | 23.8 ± 0.52 | 28.1 ± 0.52 | 23.7 ± 0.51 | 28.4 ± 0.46 |

| Blood glucose, mmol/l | 15.5 ± 1.24 | 17.0 ± 1.47 | 17.1 ± 0.86 | 16.9 ± 0.82 |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 1.31 ± 0.29 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 1.25 ± 0.17 |

| Max running test, stop speed, m/s | 0.59 ± 0.02 | 0.56 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 0.57 ± 0.02 |

| Female | ||||

| Body weight, g | 20.1 ± 0.30 | 28.3 ± 0.97 | 20.3 ± 0.24 | 27.6 ± 0.58 |

| MRI - fat mass, g | 2.06 ± 0.12 | 5.33 ± 0.59 | 1.97 ± 0.11 | 5.01 ± 0.62 |

| MRI - lean mass, g | 17.1 ± 0.27 | 22.3 ± 0.43 | 16.9 ± 0.28 | 22.0 ± 0.27 |

| Blood glucose, mmol/l | 15.5 ± 1.72 | 15.6 ± 1.11 | 13.9 ± 0.76 | 17.8 ± 1.52 |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.08 | 0.55 ± 0.04 | 0.73 ± 0.05 |

| Max running test, stop speed, m/s | 0.55 ± 0.01 | 0.56 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.02 | 0.56 ± 0.02 |

All values are shown as means ± SE. Mice were injected with 2 g/kg body wt d-glucose for the intraperitoneal glucose tolerancew test. Blood glucose values are measured 20 min post-glucose injection together with a 50-µl blood sample to measure insulin levels. Young adult mice: 8–13 wk old, mature adult mice: 18–23 wk old; n = 9–10 mice.

Fig. 2.

β-Actin KO mice display no whole body metabolic phenotype. Respiratory exchange ratio (RER) during baseline (72 h), fasting (24 h), refeed (72 h), and high-fat diet (HFD; 48 h) conditions were measured in young adult (8–13 wk old; A–D) female and mature adult (18–23 wk old; E–H) male mice; n = 8. Measurements were obtained in both young and mature adult male and female mice, showing the same pattern in both sexes with no genotype-related differences. Gray bars indicate dark hours. Values shown are means ± SE.

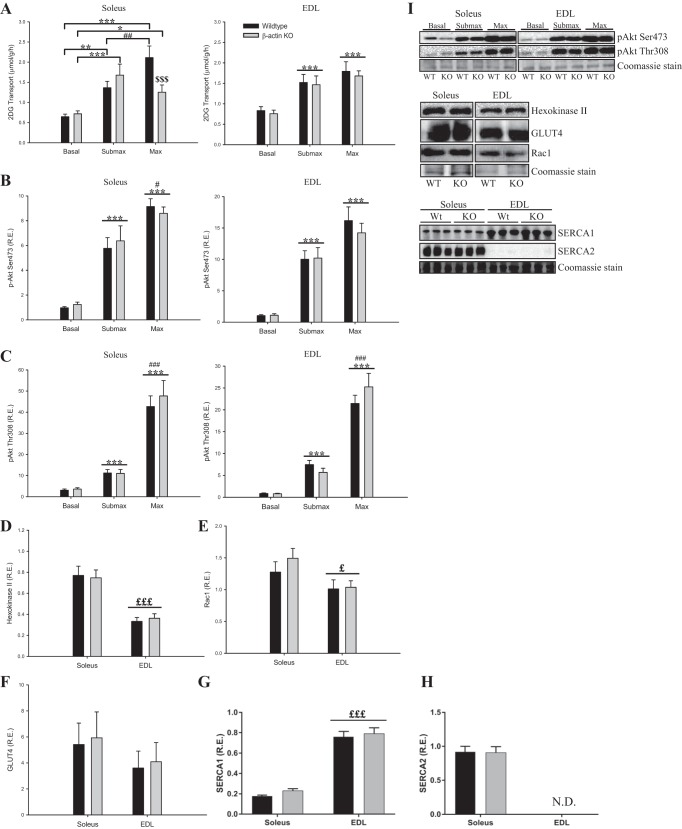

Young adult β-actin KO mice display decreased maximal insulin-stimulated glucose transport into soleus but not EDL muscle.

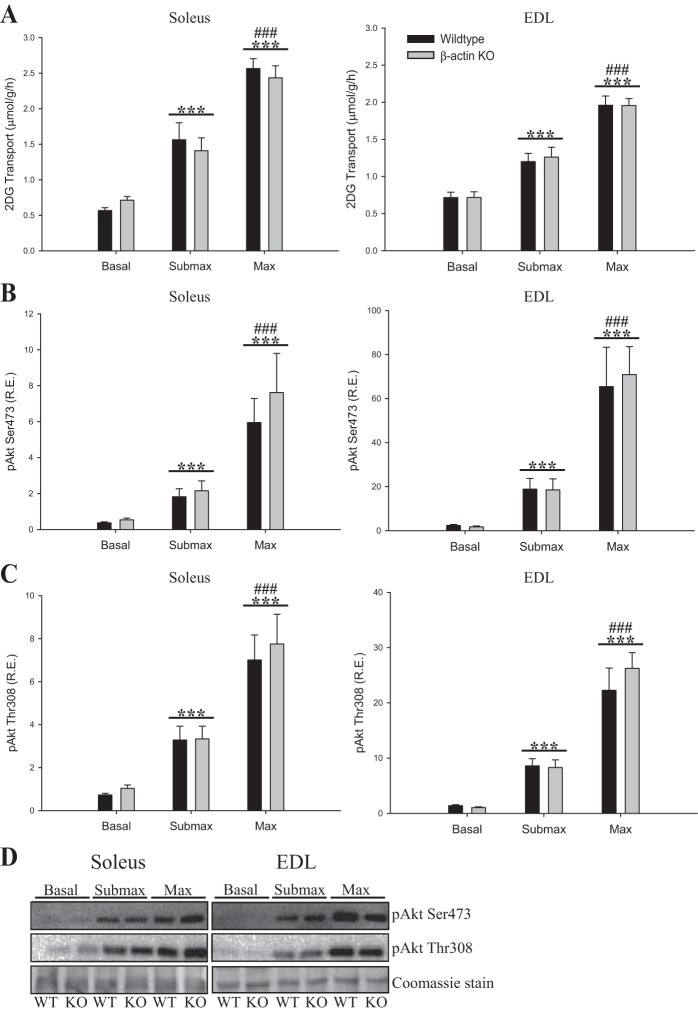

The slow-twitch oxidative soleus and the fast-twitch glycolytic EDL muscles were investigated ex vivo. In our current experiments, young adult β-actin KO mice showed a sex-independent 40% reduction in maximal insulin-stimulated glucose transport in soleus (Fig. 4A). Surprisingly, submaximal insulin-stimulated glucose transport was not reduced in the absence of β-actin (Fig. 4A), nor were there differences in insulin-stimulated glucose transport into EDL (Fig. 4A). In terms of signaling, we found no differences in insulin-related Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 4, B–C). Likewise, we found no differences in the expression of hexokinase II, GLUT4, the actin cytoskeleton-regulating GTPase Rac1, or the Ca2+ handling proteins SERCA1 and SERCA2 (Fig. 4, D–I). We conclude that β-actin is necessary to attain maximal rates of insulin-stimulated glucose transport in slow-twitch muscle of young adult mice, and this is likely not related to defects in Ca2+ handling.

Fig. 4.

2-Deoxyglucoes (2-DG) transport and insulin signaling during submaximal and maximal insulin stimulation in young adult mice. A: insulin-stimulated 2-DG transport during submaximal (soleus 1.8 nM, EDL 3 nM) and maximal (60 nM) insulin concentrations in soleus and EDL muscles from young adult (8–13 wk old) WT and β-actin KO mice. Akt Ser473 (B) and Akt Thr308 (C) phosphorylation in soleus and EDL muscles from young adult WT and β-actin KO mice, as well as total protein expression of hexokinase II (D), Rac1 (E), GLUT4 (F), sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA1; G) and SERCA2 (H) in soleus and EDL muscles from WT and β-actin KO mice; n = 10–15. I: representative blots of quantified proteins. Coomassie staining was used as loading control. All values shown are means ± SE; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. basal; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 max vs. submax insulin; $$$P < 0.001 genotype difference; £P < 0.05, £££P < 0.001 soleus vs. EDL.

Maximal insulin-stimulated glucose transport is not reduced in mature adult β-actin KO mice.

According to the original report, adult mice, 12–24 wk old, begin to show signs of myopathy with 5–10% centronucleated fibers in weight-bearing muscles such as quadriceps and triceps, whereas non-weight-bearing muscles including tibialis anterior, EDL, and diaphragm are much less affected (57). Since soleus is a weight-bearing postural muscle, we hypothesized that allowing the mice to age would further aggravate the reduction in insulin-stimulated glucose transport observed in young adult mice. Surprisingly, the difference in maximal insulin-stimulated glucose transport in soleus from young adult mice was absent in the mature adult cohort (Fig. 5A) and we found neither β-actin KO effect on insulin-stimulated glucose transport in EDL muscles (Fig. 5A), nor β-actin KO effect on cell signaling (Fig. 5, B–D). Loss of β-actin might be more critical in young adult muscles because of the ongoing growth and maturation, higher β-actin abundance (data not shown), and/or the higher habitual activity level (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

2-DG transport and insulin signaling during submaximal and maximal insulin stimulation in mature adult mice. A: insulin-stimulated 2-DG transport during submaximal (soleus 1.8 nM, EDL 3 nM) and maximal (60 nM) insulin concentrations in soleus and EDL muscles from mature adult (18–23 wk old) WT and β-actin KO mice. Akt Ser473 (B) and Akt Thr308 (C) phosphorylation in soleus and EDL muscles from mature adult WT and β-actin KO mice; n = 12 for submaximal insulin and n = 19–21 for maximal insulin stimulation. D: representative blots of Akt Ser473 and Akt Thr308 protein phosphorylation in soleus and EDL muscles of mature adult WT and β-actin KO mice. Coomassie staining is used as loading control. All values shown are means ± SE; ***P < 0.001 vs. basal; ###P < 0.001 max vs. submax insulin.

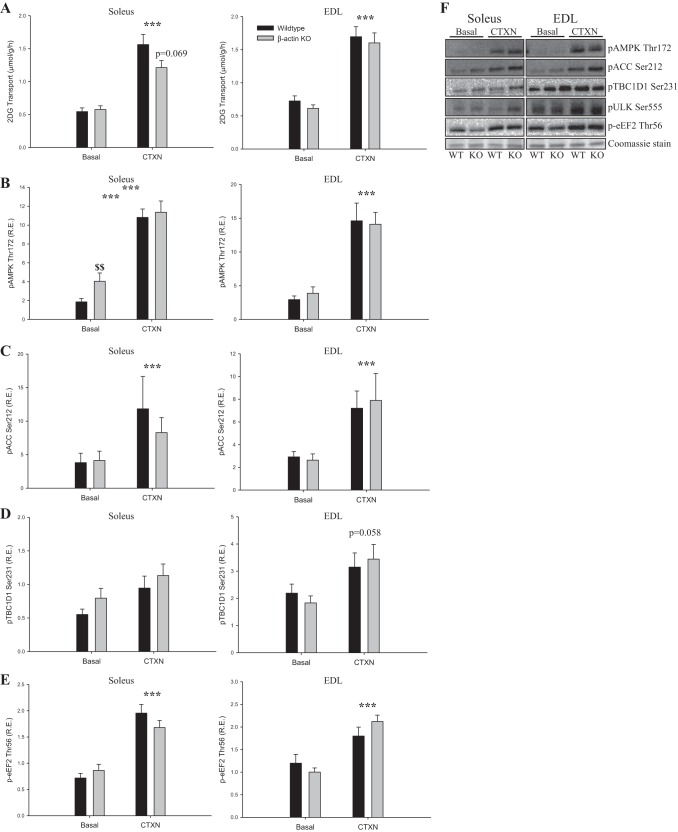

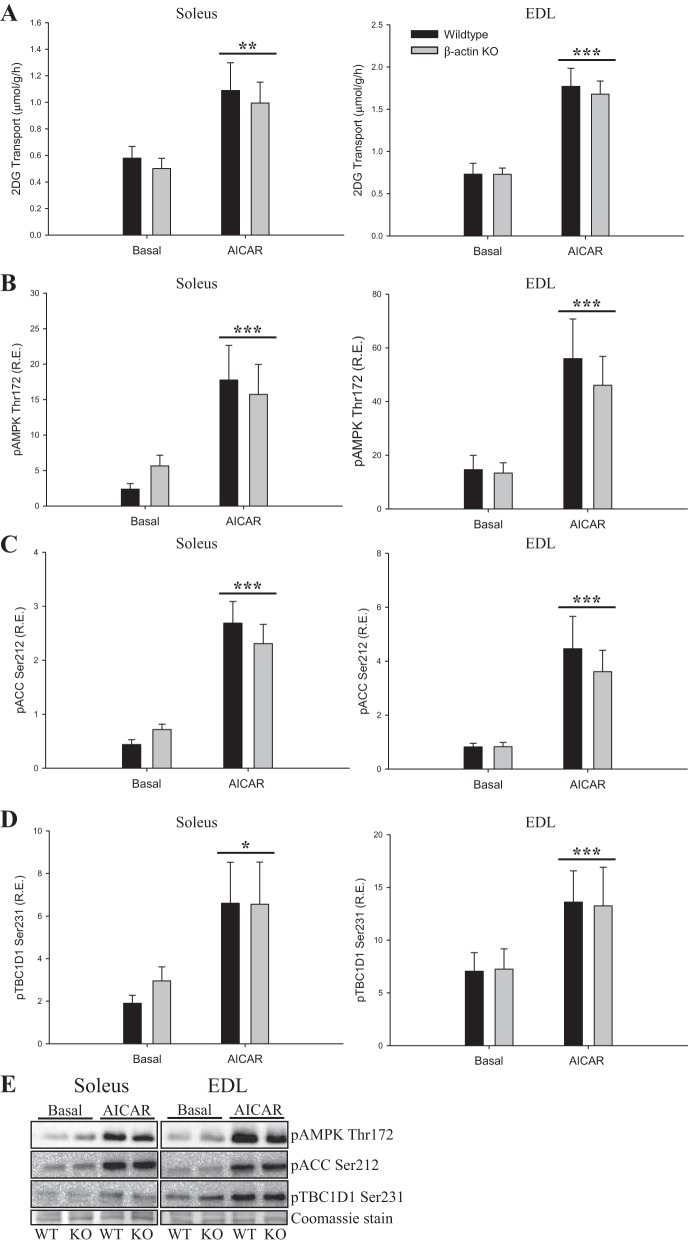

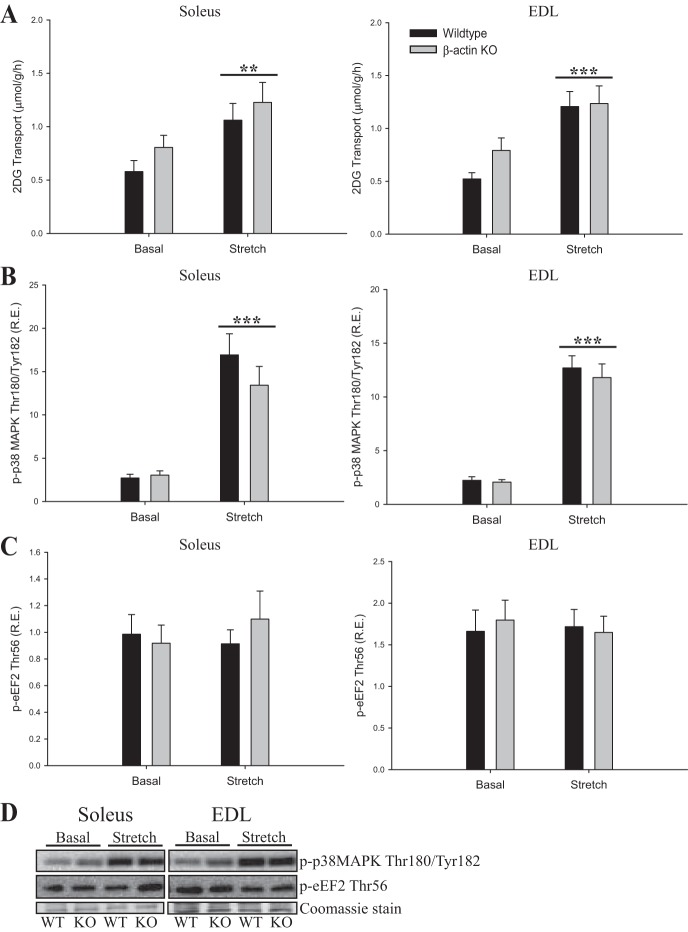

Ex vivo 2-DG glucose transport in young adult β-actin KO mice trends downward following electrically stimulated contractions but not with passive stretch or AICAR stimulation.

Exercise signaling to glucose transport is distinct from the proximal insulin signaling cascade and is known to recruit a different subset of GLUT4 vesicles (55). To evaluate whether contraction-stimulated glucose transport was impaired in young adult β-actin KO mice, we measured electrically induced contraction-stimulated glucose transport ex vivo. Similar to the insulin data, we observed reduced contraction-stimulated glucose transport in soleus but not in EDL muscles. However, the reduction was more variable than for insulin stimulation and did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 6A). The increases in glucose transport by the AMPK activator AICAR or by passive stretching of the muscles showed no changes related to β-actin (Figs. 7A and 8A). Finally, no genotype-related differences were observed in signaling pathways known to be involved in contraction-, AICAR-, or stretch-stimulated glucose transport (p-AMPK Thr172, p-ACC Ser212, p-TBC1D1 Ser231, p-eEF2 Thr56, p-p38MAPK Thr180/Tyr182; Figs. 6, B–F; 7, B–E; 8, B–D). Taken together, the ex vivo analyses indicate that the majority of the glucose transport regulation in adult skeletal muscle occurs independently of β-actin, which is in great contrast to studies in cultured muscle cells.

Fig. 6.

2-DG transport during electrically stimulated contraction (CTXN) and contraction-mediated signaling in young adult mice. A: contraction-stimulated 2-DG transport during electrical stimulation in soleus and EDL muscles from young adult (8–13 wk old) WT and β-actin KO mice. AMP-activated protein kinase(AMPK) Thr172 (B), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) Ser212 (C), TBC1 domain family member 1 (TBC1D1) Ser231 (D), and eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) Thr56 (E) phosphorylation in soleus and EDL muscles from young adult WT and β-actin KO mice. F: representative blots of AMPK Thr172, ACC Ser212, TBC1D1 Ser231, and eEF2 Thr56 protein phosphorylation in soleus and EDL muscles of young adult WT and β-actin KO mice; n = 28–29. Coomassie staining is used as loading control. All values shown are means ± SE; ***P < 0.001 vs. basal; $$P < 0.01 genotype difference.

Fig. 7.

2-DG transport during 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR) stimulation and AICAR-mediated signaling in young adult mice. A: AICAR-stimulated (4 mM) 2-DG transport in soleus and EDL muscles from young adult (8–13 wk old) WT and β-actin KO mice. AMPK Thr172 (B), ACC Ser212 (C), and TBC1D1 Ser231 (D) phosphorylation in soleus and EDL muscles from young adult WT and β-actin KO mice; n = 12. E: representative blots of AMPK Thr172, ACC Ser212, and TBC1D1 Ser231 protein phosphorylation in soleus and EDL muscles of young adult WT and β-actin KO mice. Coomassie staining is used as loading control. All values shown are means ± SE; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. basal.

Fig. 8.

2-DG transport during passive stretch stimulation and stretch-mediated signaling in young adult mice. A: stretch-stimulated (130 mN) 2-DG transport in soleus and EDL muscles from young adult (8–13 wk old) WT and β-actin KO mice. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) Thr180/Tyr182 (B), and eEF2 Thr56 (C) phosphorylation in soleus and EDL muscles from young adult WT and β-actin KO mice. No increase in eEF2 phosphorylation indicates that the muscles were not stretched excessively, which otherwise might lead to Ca2+ influx through the plasma membrane; n = 16. D: representative blots of p-p38 MAPK Thr180/Tyr180 and p-eEF2 Thr56 protein phosphorylation in soleus and EDL muscles of young adult WT and β-actin KO mice. Coomassie staining is used as loading control. All values shown are mean ± SE; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. basal.

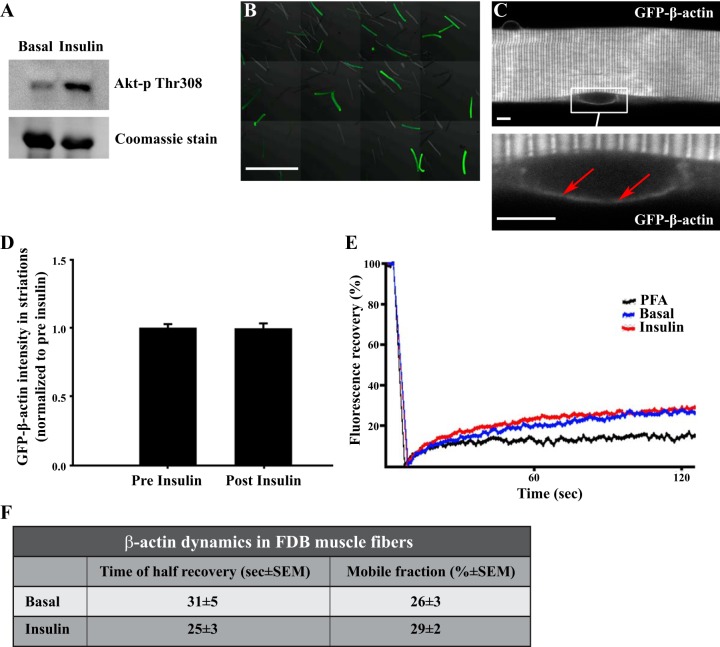

β-Actin mobility does not increase upon insulin stimulation.

The insulin-stimulated actin remodeling necessary for GLUT4 translocation is thought to be associated with increased dynamics and continuous movement of the actin cytoskeleton in muscle cells in culture (10). To test whether insulin stimulation increased actin motility in mature mouse skeletal muscle, we performed a FRAP analysis of nonstimulated and insulin-stimulated motility of electroporated GFP-β-actin in single, live FDB muscle fibers. The only published similar experiment was done in isolated feline cardiac fibers and found increased β-actin half-time of recovery with insulin stimulation (1). The increase in dynamics of GFP-β-actin in insulin-stimulated cardiomyocytes was observed in regions including the z-disks (1). However, the mobile fraction of the GFP-β-actin was not stated, making it difficult to interpret these observations. We validated our construct by transfecting C2 myoblasts and verifying that GFP showed an actin stress fiber-like morphology and colocalized with β-actin antibody staining (data not shown). We also verified that the electroporated FDB fibers responded as expected in regard to Akt phosphorylation by insulin (Fig. 9A) and that a portion of the fibers from a FDB muscle expressed detectable GFP-β-actin (Fig. 9B). In general, GFP-β-actin was expressed in a striated pattern (Fig. 9C) that colocalized with the z-disk protein α-actinin (data not shown). This expression pattern is similar to what has been reported for β-actin in cardiomyocytes (1) and for GFP-γ-actin in FDB muscle fibers (52). We also found GFP-β-actin in an additional band between the z-disks, corresponding to the A-band region, and around nuclei (Fig. 9C). No changes were observed in the intensity of the β-actin signal in striations upon insulin stimulation (Fig. 9D). When FRAP analyses were applied to this region in the muscle fibers, we could not detect any mobility of GFP-β-actin or changes with insulin (data not shown). Since it is the cortical fraction of β-actin that is considered involved in glucose transport (9), FRAP analyses were performed on GFP-β-actin localized in the superficial part of the muscle fibers in a well-defined region surrounding the nuclei (data not shown). It is likely that the achieved level of GFP-β-actin expression is insufficient to cause its incorporation into the muscle contractile filaments, as was the case for highly overexpressed γ-actin (26), but, just in case, the cortical region surrounding the nuclei was chosen for analysis to avoid potentially immobile β-actin in the contractile filaments. In these regions, the GFP-β-actin in live muscle fibers displayed greater mobility than that in control muscle fibers fixed with formaldehyde (Fig. 9E). However, insulin stimulation changed neither the mobile fraction nor the half-time of recovery of GFP-β-actin (Fig. 9, E and F). Although the FRAP analysis cannot exclude actin reorganization within the bleached region, or assess whether β-actin mobility equates to actin reorganization, the limited to null FRAP recovery of GFP-β-actin in insulin-stimulated as well as unstimulated muscle fibers, indicates that insulin stimulation does not elicit a major change in β-actin mobility in adult skeletal muscle.

Fig. 9.

A fraction of GFP-β-actin is mobile but not affected by insulin stimulation. A: Akt Thr308 phosphorylation in overnight-cultered flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) single fibers with and without 30 min of prior insulin stimulation (60 nM). B: overview of live single fibers isolated from a p-EGFP-actin-transfected FDB muscle. Bar = 1 mm. C: GFP-β-actin structure in successfully transfected live single fiber. Top: characteristic striated pattern, which was observed throughout the core of the fibers. Bottom: GFP-β-actin in the region surrounding a nucleus (arrows). Bar = 5 µm. D: GFP-β-actin intensity accumulation in striations relative to total GFP-β-actin intensity in live single fibers before and 10 min after insulin stimulation (60 nM); n = 3. E: average fluorescence recovery curve after photobleaching (FRAP) of FDB fibers with and without 30 min of prior insulin stimulation (60 nM); n = 41–43 from 3 independent experiments. As a negative control, fibers (n = 17) were fixed before the FRAP experiment. F: mean time of half recovery and mobile fraction from recovery curves fitted using a single-term exponential equation, as described in Ref. 60; n = 41–43 from 3 independent experiments. All values shown are means ± SE.

DISCUSSION

β-Actin has been proposed as the major actin isoform required for GLUT4 translocation in muscle and fat cells (6, 77). However, here, we demonstrate that β-actin is unlikely to play a major role in the GLUT4 translocation mechanism in mature mouse muscle, since glucose transport stimulation in β-actin KO muscle was indistinguishable from that in wild type under all conditions except maximal insulin stimulation in young adult soleus muscles. Increasing the age of the mice from 8–13 wk to 18–23 wk caused the glucose transport phenotype in the soleus muscle of the β-actin KO mice to disappear, suggesting that it might relate to muscle growth/maturation or be observable only at very high glucose transport rates in young mice. Furthermore, our FRAP analysis of overexpressed GFP-β-actin suggests that the β-actin cytoskeleton is largely static and unresponsive to insulin in adult mouse muscle. The imaging analyses were performed in FDB muscle fibers, whereas the ex vivo characterization was done in soleus and EDL muscles. Although the EDL and FDB muscles are both characterized by high proportions of type II fibers (3), and we consider a genotype-related difference in FDB unlikely, based on our EDL incubation data, we cannot exclude potential muscle type-specific differences.

Studies using the actin depolymerizing agent latrunculin B suggest the requirement of the actin cytoskeleton in insulin-, contraction-, and stretch-stimulated glucose transport (7, 68, 69, 71). In addition, a number of studies have suggested that the function and regulation of the cortical actin cytoskeleton are conserved between muscle cell culture and mature muscle. Our group (68–70) and others (24, 79) demonstrated that the small Rho family GTPase Rac1 is activated by insulin, passive stretch, and contraction/exercise in rodents and humans and is necessary for insulin-, stretch-, contraction-, and exercise-stimulated GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake in mouse muscle (68, 69, 71–73). This effect was nonadditive to that of latrunculin B, suggesting that the effects of Rac1 require an intact actin cytoskeleton (68, 70). A role for Rac1 is also supported by reduced insulin-stimulated glucose transport and GLUT4 translocation in mice lacking the Rac1-activated kinase PAK1 (78). This is consistent with the proposed involvement of Rac1 signaling in insulin-stimulated cortical actin remodeling and GLUT4 translocation in muscle cell culture (34). These data indicate that Rac1 signaling regulates actin dynamics and consequently glucose transport in mature muscle. There are several possible explanations for the discrepancy between muscle-specific β-actin KO mice and Rac1 KO mice. First, although it seems unlikely, based on the literature (8, 16, 31, 57, 65), we cannot rule out that γ-actin partly compensated for the absence of β-actin, as also suggested recently by others (43, 53). One study found γ-actin to be the main constituent of the cortical actin mesh in various rat and pig fibroblast cell cultures (16), and another study showed γ-actin, but not β-actin, staining in mechanically peeled sarcolemma from mouse muscle fibers (61). Furthermore, genetic manipulations to remove or increase expression of tropomyosin 3.1 (Tpm3.1) in skeletal muscle correlate with glucose uptake during glucose and insulin tolerance tests, and Tpm3.1 interestingly defines a subset of γ-actin filaments located at the sarcolemma and T-tubules (32). Since latrunculin B disrupts all actin isoforms, it might be speculated that the previously reported Rac1-dependent reduction in glucose transport by this compound occurs via either γ-actin or both β- and γ-actin. Second, Rac1 and PAK1 might control GLUT4 translocation and glucose transport through non-actin-dependent mechanisms. Rac1 is a subunit of the NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) complex, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) can influence GLUT4 translocation and glucose transport both positively and negatively (2, 13, 21, 29, 39, 62, 67). NOX2 is known to interact with the actin cytoskeleton, and latrunculin B and other actin depolymerizing agents were found to increase basal or stimulated NOX2 activity in different nonmuscle cell types (4, 11). Since NOX2 is the major source of ROS during in vitro contraction and stretch (33, 82) and may signal to insulin-stimulated muscle GLUT4 translocation (13) and contribute to insulin resistance (14, 66), the exact roles of actin and NOX2 and their potential cross-talk downstream of Rac1 in regulating glucose transport deserves further study. If the absence of actin isoforms in skeletal muscle increases basal or stimulated NOX2 activation, it might have contributed to the present insulin-resistant phenotype in soleus muscles from young mice. Furthermore, if the absence of actin isoforms in skeletal muscle increases basal or stimulated NOX2 activation, it might also contribute to the progressive myopathy in mice lacking β- and/or γ-actin (57, 58, 65).

To evaluate whether the previously reported progressive myopathy in β-actin KO mice would affect glucose transport, we performed our measurements in two cohorts of mice, young adult and mature adult. The mature adult cohort was chosen because all muscles measured in the original report at 6 mo (52) showed a significant, albeit highly variable, genotype difference in centronucleated fibers, indicative of muscle regeneration. In contrast to our hypothesis that muscle damage-associated inflammation in the aged β-actin KO mice would impair insulin-stimulated glucose transport, we observed a partial reduction in maximal insulin-stimulated glucose transport in the soleus muscles of the young adult β-actin KO mice, which was absent in the mature adult mice. Even in young mice, this phenotype was observed only with maximal insulin stimulation and only in soleus muscle. We speculate that this phenotype relates to the interaction of the load-bearing postural soleus muscle with the rapid postnatal muscle growth phase. For instance, an ~14-fold increase in mouse EDL fiber volume occurs between weeks 1 and 8 post partum (83). Another recent study compared the effect of satellite cell depletion on synergist ablation-induced hypertrophy of the plantaris muscle in 8- and 16-wk-old mice and observed a strong inhibitory effect in young but not mature adult mice (42). Whether these two phenotypes are related and whether the involvement of β-actin is direct or indirect are presently unknown. Another possibility is that a genotype difference in glucose transport is evident only at very high glucose transport rates in very insulin-sensitive young mice. However, the fold increase in glucose transport did not differ between the two age groups, making this an unlikely explanation.

Despite the known downregulation of β- and γ-actin during muscle cell differentiation (20, 37, 51, 61, 76), and despite previous reports of exclusive β-actin localization to the neuromuscular junction (19, 38), what might the function of β-actin then be if present throughout mature skeletal muscle? Apart from a role in vesicle movement beyond those containing GLUT4, it may play a role in glycogen resynthesis. After in situ contraction-mediated glycogen depletion in rabbit tibialis anterior muscle, β-actin was reported to colocalize with glycogen synthase and phosphorylase in the spherical glycogen synthesis-initiating structures termed glycosomes (56). Furthermore, β-actin expression in membrane-enriched fractions correlated with so-called transversal stiffness (i.e., nonlongitudinal force transmission perpendicular to the length of the fibers) measured using atomic force microscopy in rodent soleus muscles subjected to unloading by hindlimb suspension or space flight (45–49). Interestingly, actinin-4 showed a similar decrease in membranes with unloading as β-actin (45, 47) and was proposed to link GLUT4 translocation to the cytoskeleton in L6 muscle cells (17, 74). Finally, the actin cytoskeleton positions many organelles, and β-actin might participate in this process, too. To give a few examples from nonmuscle cell types, the actin cytoskeleton positions mitochondria, perhaps through mitochondrial myosin 19 isoform (59) and nuclei, or through A-type lamins and the nuclear envelope proteins Nesprin and Sun (50). The above-mentioned clearly highlights the significance of using the muscle-specific β-actin KO mice in future studies to unravel the role of β-actin in mature skeletal muscle.

In summary, the present study examined the contribution of β-actin to glucose transport regulation in adult mouse muscles. The β-actin KO mice showed a surprisingly mild phenotype, implying that the β-actin cytoskeleton might behave differently and is not as crucial for GLUT4 translocation in adult muscle as indicated by previous cell culture studies. Instead, the closely related γ-actin isoform might be the main actin isoform involved. Further studies are required to scrutinize which actin isoform is involved in the actin cytoskeleton rearrangements facilitating GLUT4 translocation and glucose transport in adult muscle.

GRANTS

The study was supported by funding from a Novo Nordisk Foundation Excellence Grant (no. 15182) to T. E. Jensen, Danish Diabetes Academy PhD stipends supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation to A. B. Madsen and J. R. Knudsen, and Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases to E. Ralston.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.E.J. conceived and designed research; A.B.M., J.R.K., C.H.-O., Y.A., K.J.Z., L.S., P.S., and T.E.J. performed experiments; A.B.M., J.R.K., C.H.-O., Y.A., K.J.Z., L.S., and P.S. analyzed data; A.B.M., J.R.K., K.J.Z., P.S., E.R., and T.E.J. interpreted results of experiments; A.B.M., J.R.K., and C.H.-O. prepared figures; A.B.M., E.R., and T.E.J. drafted manuscript; A.B.M., J.R.K., C.H.-O., Y.A., K.J.Z., L.S., P.S., E.R., and T.E.J. edited and revised manuscript; A.B.M., J.R.K., C.H.-O., Y.A., K.J.Z., L.S., P.S., E.R., and T.E.J. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Betina Blomgren and Irene Bech Nielsen analyzed the plasma insulin. The pEGFP-actin plasmid was a kind gift from A. Klip (no. 6116-1, Clontech Laboratories). The muscle-specific β-actin KO mice were a kind gift from James M. Ervasti (Dept. of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, and Biophysics, Univ. of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN).

REFERENCES

- 1.Balasubramanian S, Mani SK, Kasiganesan H, Baicu CC, Kuppuswamy D. Hypertrophic stimulation increases beta-actin dynamics in adult feline cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 5: e11470, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balteau M, Tajeddine N, de Meester C, Ginion A, Des Rosiers C, Brady NR, Sommereyns C, Horman S, Vanoverschelde JL, Gailly P, Hue L, Bertrand L, Beauloye C. NADPH oxidase activation by hyperglycaemia in cardiomyocytes is independent of glucose metabolism but requires SGLT1. Cardiovasc Res 92: 237–246, 2011. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banas K, Clow C, Jasmin BJ, Renaud JM. The KATP channel Kir6.2 subunit content is higher in glycolytic than oxidative skeletal muscle fibers. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R916–R925, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00663.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bengtsson T, Orselius K, Wetterö J. Role of the actin cytoskeleton during respiratory burst in chemoattractant-stimulated neutrophils. Cell Biol Int 30: 154–163, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergeron SE, Zhu M, Thiem SM, Friderici KH, Rubenstein PA. Ion-dependent polymerization differences between mammalian beta- and gamma-nonmuscle actin isoforms. J Biol Chem 285: 16087–16095, 2010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brozinick JT Jr, Berkemeier BA, Elmendorf JS. “Actin”g on GLUT4: membrane & cytoskeletal components of insulin action. Curr Diabetes Rev 3: 111–122, 2007. doi: 10.2174/157339907780598199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brozinick JT Jr, Hawkins ED, Strawbridge AB, Elmendorf JS. Disruption of cortical actin in skeletal muscle demonstrates an essential role of the cytoskeleton in glucose transporter 4 translocation in insulin-sensitive tissues. J Biol Chem 279: 40699–40706, 2004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402697200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunnell TM, Burbach BJ, Shimizu Y, Ervasti JM. β-Actin specifically controls cell growth, migration, and the G-actin pool. Mol Biol Cell 22: 4047–4058, 2011. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e11-06-0582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiu TT, Jensen TE, Sylow L, Richter EA, Klip A. Rac1 signalling towards GLUT4/glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Cell Signal 23: 1546–1554, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiu TT, Patel N, Shaw AE, Bamburg JR, Klip A. Arp2/3- and cofilin-coordinated actin dynamics is required for insulin-mediated GLUT4 translocation to the surface of muscle cells. Mol Biol Cell 21: 3529–3539, 2010. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e10-04-0316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choy JS, Lu X, Yang J, Zhang ZD, Kassab GS. Endothelial actin depolymerization mediates NADPH oxidase-superoxide production during flow reversal. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H69–H77, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00402.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun KH, Choi KD, Lee DH, Jung Y, Henry RR, Ciaraldi TP, Kim YB. In vivo activation of ROCK1 by insulin is impaired in skeletal muscle of humans with type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300: E536–E542, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00538.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contreras-Ferrat A, Llanos P, Vásquez C, Espinosa A, Osorio-Fuentealba C, Arias-Calderon M, Lavandero S, Klip A, Hidalgo C, Jaimovich E. Insulin elicits a ROS-activated and an IP3-dependent Ca2+ release, which both impinge on GLUT4 translocation. J Cell Sci 127: 1911–1923, 2014. doi: 10.1242/jcs.138982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costford SR, Castro-Alves J, Chan KL, Bailey LJ, Woo M, Belsham DD, Brumell JH, Klip A. Mice lacking NOX2 are hyperphagic and store fat preferentially in the liver. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 306: E1341–E1353, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00089.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DiFranco M, Quinonez M, Capote J, Vergara J. DNA transfection of mammalian skeletal muscles using in vivo electroporation. J Vis Exp (32): 1520, 2009. doi: 10.3791/1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dugina V, Zwaenepoel I, Gabbiani G, Clément S, Chaponnier C. Beta and gamma-cytoplasmic actins display distinct distribution and functional diversity. J Cell Sci 122: 2980–2988, 2009. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster LJ, Rudich A, Talior I, Patel N, Huang X, Furtado LM, Bilan PJ, Mann M, Klip A. Insulin-dependent interactions of proteins with GLUT4 revealed through stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC). J Proteome Res 5: 64–75, 2006. doi: 10.1021/pr0502626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Habegger KM, Penque BA, Sealls W, Tackett L, Bell LN, Blue EK, Gallagher PJ, Sturek M, Alloosh MA, Steinberg HO, Considine RV, Elmendorf JS. Fat-induced membrane cholesterol accrual provokes cortical filamentous actin destabilisation and glucose transport dysfunction in skeletal muscle. Diabetologia 55: 457–467, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2334-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall ZW, Lubit BW, Schwartz JH. Cytoplasmic actin in postsynaptic structures at the neuromuscular junction. J Cell Biol 90: 789–792, 1981. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.3.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanft LM, Rybakova IN, Patel JR, Rafael-Fortney JA, Ervasti JM. Cytoplasmic gamma-actin contributes to a compensatory remodeling response in dystrophin-deficient muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 5385–5390, 2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600980103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higaki Y, Mikami T, Fujii N, Hirshman MF, Koyama K, Seino T, Tanaka K, Goodyear LJ. Oxidative stress stimulates skeletal muscle glucose uptake through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathway. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 294: E889–E897, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00150.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill MA, Gunning P. Beta and gamma actin mRNAs are differentially located within myoblasts. J Cell Biol 122: 825–832, 1993. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoock TC, Newcomb PM, Herman IM. Beta actin and its mRNA are localized at the plasma membrane and the regions of moving cytoplasm during the cellular response to injury. J Cell Biol 112: 653–664, 1991. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.4.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu F, Li N, Li Z, Zhang C, Yue Y, Liu Q, Chen L, Bilan PJ, Niu W. Electrical pulse stimulation induces GLUT4 translocation in a Rac-Akt-dependent manner in C2C12 myotubes. FEBS Lett 592: 644–654, 2018. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Delvecchio K, Feng HZ, Cartee GD, Jin JP, Shisheva A. Muscle-specific Pikfyve gene disruption causes glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, adiposity, and hyperinsulinemia but not muscle fiber-type switching. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305: E119–E131, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00030.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaeger MA, Sonnemann KJ, Fitzsimons DP, Prins KW, Ervasti JM. Context-dependent functional substitution of alpha-skeletal actin by gamma-cytoplasmic actin. FASEB J 23: 2205–2214, 2009. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.JeBailey L, Wanono O, Niu W, Roessler J, Rudich A, Klip A. Ceramide- and oxidant-induced insulin resistance involve loss of insulin-dependent Rac-activation and actin remodeling in muscle cells. Diabetes 56: 394–403, 2007. doi: 10.2337/db06-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen TE, Rose AJ, Jørgensen SB, Brandt N, Schjerling P, Wojtaszewski JF, Richter EA. Possible CaMKK-dependent regulation of AMPK phosphorylation and glucose uptake at the onset of mild tetanic skeletal muscle contraction. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E1308–E1317, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00456.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen TE, Schjerling P, Viollet B, Wojtaszewski JF, Richter EA. AMPK alpha1 activation is required for stimulation of glucose uptake by twitch contraction, but not by H2O2, in mouse skeletal muscle. PLoS One 3: e2102, 2008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karakozova M, Kozak M, Wong CC, Bailey AO, Yates JR III, Mogilner A, Zebroski H, Kashina A. Arginylation of beta-actin regulates actin cytoskeleton and cell motility. Science 313: 192–196, 2006. doi: 10.1126/science.1129344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kee AJ, Gunning PW, Hardeman EC. Diverse roles of the actin cytoskeleton in striated muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 30: 187–197, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s10974-009-9193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kee AJ, Yang L, Lucas CA, Greenberg MJ, Martel N, Leong GM, Hughes WE, Cooney GJ, James DE, Ostap EM, Han W, Gunning PW, Hardeman EC. An actin filament population defined by the tropomyosin Tpm3.1 regulates glucose uptake. Traffic 16: 691–711, 2015. doi: 10.1111/tra.12282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerr JP, Robison P, Shi G, Bogush AI, Kempema AM, Hexum JK, Becerra N, Harki DA, Martin SS, Raiteri R, Prosser BL, Ward CW. Detyrosinated microtubules modulate mechanotransduction in heart and skeletal muscle. Nat Commun 6: 8526, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khayat ZA, Tong P, Yaworsky K, Bloch RJ, Klip A. Insulin-induced actin filament remodeling colocalizes actin with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and GLUT4 in L6 myotubes. J Cell Sci 113: 279–290, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kislauskis EH, Zhu X, Singer RH. beta-Actin messenger RNA localization and protein synthesis augment cell motility. J Cell Biol 136: 1263–1270, 1997. [Erratum. J Cell Biol 137: 1683, 1997.] doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Y, Lai YC, Hill EV, Tyteca D, Carpentier S, Ingvaldsen A, Vertommen D, Lantier L, Foretz M, Dequiedt F, Courtoy PJ, Erneux C, Viollet B, Shepherd PR, Tavaré JM, Jensen J, Rider MH. Phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate 5-kinase (PIKfyve) is an AMPK target participating in contraction-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Biochem J 455: 195–206, 2013. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lloyd CM, Berendse M, Lloyd DG, Schevzov G, Grounds MD. A novel role for non-muscle gamma-actin in skeletal muscle sarcomere assembly. Exp Cell Res 297: 82–96, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lubit BW. Association of beta-cytoplasmic actin with high concentrations of acetylcholine receptor (AChR) in normal and anti-AChR-treated primary rat muscle cultures. J Histochem Cytochem 32: 973–981, 1984. doi: 10.1177/32.9.6379042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merry TL, Wadley GD, Stathis CG, Garnham AP, Rattigan S, Hargreaves M, McConell GK. N-acetylcysteine infusion does not affect glucose disposal during prolonged moderate-intensity exercise in humans. J Physiol 588: 1623–1634, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.184333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molero JC, Jensen TE, Withers PC, Couzens M, Herzog H, Thien CB, Langdon WY, Walder K, Murphy MA, Bowtell DD, James DE, Cooney GJ. c-Cbl-deficient mice have reduced adiposity, higher energy expenditure, and improved peripheral insulin action. J Clin Invest 114: 1326–1333, 2004. doi: 10.1172/JCI21480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Müller M, Diensthuber RP, Chizhov I, Claus P, Heissler SM, Preller M, Taft MH, Manstein DJ. Distinct functional interactions between actin isoforms and nonsarcomeric myosins. PLoS One 8: e70636, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murach KA, White SH, Wen Y, Ho A, Dupont-Versteegden EE, McCarthy JJ, Peterson CA. Differential requirement for satellite cells during overload-induced muscle hypertrophy in growing versus mature mice. Skelet Muscle 7: 14, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s13395-017-0132-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Rourke AR, Lindsay A, Tarpey MD, Yuen S, McCourt P, Nelson DM, Perrin BJ, Thomas DD, Spangenburg EE, Lowe DA, Ervasti JM. Impaired muscle relaxation and mitochondrial fission associated with genetic ablation of cytoplasmic actin isoforms. FEBS J 285: 481–500, 2018. doi: 10.1111/febs.14367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oddoux S, Zaal KJ, Tate V, Kenea A, Nandkeolyar SA, Reid E, Liu W, Ralston E. Microtubules that form the stationary lattice of muscle fibers are dynamic and nucleated at Golgi elements. J Cell Biol 203: 205–213, 2013. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201304063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogneva IV. Transversal stiffness and beta-actin and alpha-actinin-4 content of the M. soleus fibers in the conditions of a 3-day reloading after 14-day gravitational unloading. J Biomed Biotechnol 2011: 393405, 2011. doi: 10.1155/2011/393405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogneva IV, Biryukov NS, Leinsoo TA, Larina IM. Possible role of non-muscle alpha-actinins in muscle cell mechanosensitivity. PLoS One 9: e96395, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogneva IV, Gnyubkin V, Laroche N, Maximova MV, Larina IM, Vico L. Structure of the cortical cytoskeleton in fibers of postural muscles and cardiomyocytes of mice after 30-day 2-g centrifugation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 118: 613–623, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00812.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogneva IV, Maximova MV, Larina IM. Structure of cortical cytoskeleton in fibers of mouse muscle cells after being exposed to a 30-day space flight on board the BION-M1 biosatellite. J Appl Physiol (1985) 116: 1315–1323, 2014. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00134.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogneva IV, Mirzoev TM, Biryukov NS, Veselova OM, Larina IM. Structure and functional characteristics of rat’s left ventricle cardiomyocytes under antiorthostatic suspension of various duration and subsequent reloading. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012: 659869, 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/659869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ostlund C, Folker ES, Choi JC, Gomes ER, Gundersen GG, Worman HJ. Dynamics and molecular interactions of linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton (LINC) complex proteins. J Cell Sci 122: 4099–4108, 2009. doi: 10.1242/jcs.057075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Owens GK, Thompson MM. Developmental changes in isoactin expression in rat aortic smooth muscle cells in vivo. Relationship between growth and cytodifferentiation. J Biol Chem 261: 13373–13380, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Papponen H, Kaisto T, Leinonen S, Kaakinen M, Metsikkö K. Evidence for gamma-actin as a Z disc component in skeletal myofibers. Exp Cell Res 315: 218–225, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patrinostro X, O’Rourke AR, Chamberlain CM, Moriarity BS, Perrin BJ, Ervasti JM. Relative importance of βcyto- and γcyto-actin in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell 28: 771–782, 2017. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e16-07-0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perrin BJ, Sonnemann KJ, Ervasti JM. β-actin and γ-actin are each dispensable for auditory hair cell development but required for Stereocilia maintenance. PLoS Genet 6: e1001158, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ploug T, van Deurs B, Ai H, Cushman SW, Ralston E. Analysis of GLUT4 distribution in whole skeletal muscle fibers: identification of distinct storage compartments that are recruited by insulin and muscle contractions. J Cell Biol 142: 1429–1446, 1998. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prats C, Cadefau JA, Cussó R, Qvortrup K, Nielsen JN, Wojtaszewski JF, Hardie DG, Stewart G, Hansen BF, Ploug T. Phosphorylation-dependent translocation of glycogen synthase to a novel structure during glycogen resynthesis. J Biol Chem 280: 23165–23172, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prins KW, Call JA, Lowe DA, Ervasti JM. Quadriceps myopathy caused by skeletal muscle-specific ablation of β(cyto)-actin. J Cell Sci 124: 951–957, 2011. doi: 10.1242/jcs.079848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prins KW, Lowe DA, Ervasti JM. Skeletal muscle-specific ablation of gamma(cyto)-actin does not exacerbate the mdx phenotype. PLoS One 3: e2419, 2008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Quintero OA, DiVito MM, Adikes RC, Kortan MB, Case LB, Lier AJ, Panaretos NS, Slater SQ, Rengarajan M, Feliu M, Cheney RE. Human Myo19 is a novel myosin that associates with mitochondria. Curr Biol 19: 2008–2013, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rapsomaniki MA, Kotsantis P, Symeonidou IE, Giakoumakis NN, Taraviras S, Lygerou Z. easyFRAP: an interactive, easy-to-use tool for qualitative and quantitative analysis of FRAP data. Bioinformatics 28: 1800–1801, 2012. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rybakova IN, Patel JR, Ervasti JM. The dystrophin complex forms a mechanically strong link between the sarcolemma and costameric actin. J Cell Biol 150: 1209–1214, 2000. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sandström ME, Zhang SJ, Bruton J, Silva JP, Reid MB, Westerblad H, Katz A. Role of reactive oxygen species in contraction-mediated glucose transport in mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol 575: 251–262, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.110601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Strakova J, Shisheva A. Role for a novel signaling intermediate, phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate, in insulin-regulated F-actin stress fiber breakdown and GLUT4 translocation. Endocrinology 145: 4853–4865, 2004. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shestakova EA, Singer RH, Condeelis J. The physiological significance of beta -actin mRNA localization in determining cell polarity and directional motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 7045–7050, 2001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121146098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sonnemann KJ, Fitzsimons DP, Patel JR, Liu Y, Schneider MF, Moss RL, Ervasti JM. Cytoplasmic gamma-actin is not required for skeletal muscle development but its absence leads to a progressive myopathy. Dev Cell 11: 387–397, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Souto Padron de Figueiredo A, Salmon AB, Bruno F, Jimenez F, Martinez HG, Halade GV, Ahuja SS, Clark RA, DeFronzo RA, Abboud HE, El Jamali A. Nox2 mediates skeletal muscle insulin resistance induced by a high fat diet. J Biol Chem 290: 13427–13439, 2015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.626077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sundaresan M, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Sulciner DJ, Gutkind JS, Irani K, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Finkel T. Regulation of reactive-oxygen-species generation in fibroblasts by Rac1. Biochem J 318: 379–382, 1996. doi: 10.1042/bj3180379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sylow L, Jensen TE, Kleinert M, Højlund K, Kiens B, Wojtaszewski J, Prats C, Schjerling P, Richter EA. Rac1 signaling is required for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and is dysregulated in insulin-resistant murine and human skeletal muscle. Diabetes 62: 1865–1875, 2013. doi: 10.2337/db12-1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sylow L, Jensen TE, Kleinert M, Mouatt JR, Maarbjerg SJ, Jeppesen J, Prats C, Chiu TT, Boguslavsky S, Klip A, Schjerling P, Richter EA. Rac1 is a novel regulator of contraction-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. Diabetes 62: 1139–1151, 2013. doi: 10.2337/db12-0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sylow L, Kleinert M, Pehmøller C, Prats C, Chiu TT, Klip A, Richter EA, Jensen TE. Akt and Rac1 signaling are jointly required for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and downregulated in insulin resistance. Cell Signal 26: 323–331, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sylow L, Møller LL, Kleinert M, Richter EA, Jensen TE. Stretch-stimulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle is regulated by Rac1. J Physiol 593: 645–656, 2015. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.284281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sylow L, Møller LLV, Kleinert M, D’Hulst G, De Groote E, Schjerling P, Steinberg GR, Jensen TE, Richter EA. Rac1 and AMPK Account for the Majority of Muscle Glucose Uptake Stimulated by Ex Vivo Contraction but Not In Vivo Exercise. Diabetes 66: 1548–1559, 2017. doi: 10.2337/db16-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sylow L, Nielsen IL, Kleinert M, Møller LL, Ploug T, Schjerling P, Bilan PJ, Klip A, Jensen TE, Richter EA. Rac1 governs exercise-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle through regulation of GLUT4 translocation in mice. J Physiol 594: 4997–5008, 2016. doi: 10.1113/JP272039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Talior-Volodarsky I, Randhawa VK, Zaid H, Klip A. Alpha-actinin-4 is selectively required for insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation. J Biol Chem 283: 25115–25123, 2008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomson DM, Porter BB, Tall JH, Kim HJ, Barrow JR, Winder WW. Skeletal muscle and heart LKB1 deficiency causes decreased voluntary running and reduced muscle mitochondrial marker enzyme expression in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E196–E202, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00366.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tondeleir D, Vandamme D, Vandekerckhove J, Ampe C, Lambrechts A. Actin isoform expression patterns during mammalian development and in pathology: insights from mouse models. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 66: 798–815, 2009. doi: 10.1002/cm.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tong P, Khayat ZA, Huang C, Patel N, Ueyama A, Klip A. Insulin-induced cortical actin remodeling promotes GLUT4 insertion at muscle cell membrane ruffles. J Clin Invest 108: 371–381, 2001. doi: 10.1172/JCI200112348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tunduguru R, Chiu TT, Ramalingam L, Elmendorf JS, Klip A, Thurmond DC. Signaling of the p21-activated kinase (PAK1) coordinates insulin-stimulated actin remodeling and glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells. Biochem Pharmacol 92: 380–388, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ueda S, Kitazawa S, Ishida K, Nishikawa Y, Matsui M, Matsumoto H, Aoki T, Nozaki S, Takeda T, Tamori Y, Aiba A, Kahn CR, Kataoka T, Satoh T. Crucial role of the small GTPase Rac1 in insulin-stimulated translocation of glucose transporter 4 to the mouse skeletal muscle sarcolemma. FASEB J 24: 2254–2261, 2010. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-137380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang H, Listrat A, Meunier B, Gueugneau M, Coudy-Gandilhon C, Combaret L, Taillandier D, Polge C, Attaix D, Lethias C, Lee K, Goh KL, Béchet D. Apoptosis in capillary endothelial cells in ageing skeletal muscle. Aging Cell 13: 254–262, 2014. doi: 10.1111/acel.12169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang Z, Oh E, Clapp DW, Chernoff J, Thurmond DC. Inhibition or ablation of p21-activated kinase (PAK1) disrupts glucose homeostatic mechanisms in vivo. J Biol Chem 286: 41359–41367, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.291500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ward CW, Prosser BL, Lederer WJ. Mechanical stretch-induced activation of ROS/RNS signaling in striated muscle. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 929–936, 2014. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.White RB, Biérinx AS, Gnocchi VF, Zammit PS. Dynamics of muscle fibre growth during postnatal mouse development. BMC Dev Biol 10: 21, 2010. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zong H, Bastie CC, Xu J, Fassler R, Campbell KP, Kurland IJ, Pessin JE. Insulin resistance in striated muscle-specific integrin receptor beta1-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 284: 4679–4688, 2009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807408200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]