Abstract

Increased vascular stiffness correlates with a higher risk of cardiovascular complications in aging adults. Elastin (ELN) insufficiency, as observed in patients with Williams-Beuren syndrome or with familial supravalvular aortic stenosis, also increases vascular stiffness and leads to arterial narrowing. We used Eln+/− mice to test the hypothesis that pathologically increased vascular stiffness with concomitant arterial narrowing leads to decreased blood flow to end organs such as the brain. We also hypothesized that drugs that remodel arteries and increase lumen diameter would improve flow. To test these hypotheses, we compared carotid blood flow using ultrasound and cerebral blood flow using MRI-based arterial spin labeling in wild-type (WT) and Eln+/− mice. We then studied how minoxidil, an ATP-sensitive K+ channel opener and vasodilator, affects vessel mechanics, blood flow, and gene expression. Both carotid and cerebral blood flows were lower in Eln+/− mice than in WT mice. Treatment of Eln+/− mice with minoxidil lowered blood pressure and reduced functional arterial stiffness to WT levels. Minoxidil also improved arterial diameter and restored carotid and cerebral blood flows in Eln+/− mice. The beneficial effects persisted for weeks after drug removal. RNA-Seq analysis revealed differential expression of 127 extracellular matrix-related genes among the treatment groups. These results indicate that ELN insufficiency impairs end-organ perfusion, which may contribute to the increased cardiovascular risk. Minoxidil, despite lowering blood pressure, improves end-organ perfusion. Changes in matrix gene expression and persistence of treatment effects after drug withdrawal suggest arterial remodeling. Such remodeling may benefit patients with genetic or age-dependent ELN insufficiency.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Our work with a model of chronic vascular stiffness, the elastin (Eln)+/− mouse, shows reduced brain perfusion as measured by carotid ultrasound and MRI arterial spin labeling. Vessel caliber, functional stiffness, and blood flow improved with minoxidil. The ATP-sensitive K+ channel opener increased Eln gene expression and altered 126 other matrix-associated genes.

Keywords: arterial stiffness, ATP-sensitive K+ channel, cerebral blood flow, elastin, extracellular matrix, vascular remodeling

INTRODUCTION

Mammalian conducting arteries are composed of alternating layers of smooth muscle and elastin (ELN)-containing fibers. ELN provides recoil to stretching arteries. With aging, ELN fibers gradually succumb to damage and loss (52), resulting in pathologically increased arterial stiffness. Increased arterial stiffness is independently associated with increased risk of sudden death, stroke, and myocardial infarction (10, 43, 57). Furthermore, increased vascular stiffness is associated with perfusion abnormalities and microvascular damage in the brain as well as a faster rate of cognitive decline in the elderly (17, 33, 51). ELN has a long half-life, ~70 yr (46), making age-associated turnover difficult to model in mice. Consequently, study of rare genetic conditions of ELN insufficiency may offer mechanistic insights into the impact of chronic vascular stiffness on end organs.

Patients with congenital ELN insufficiency [e.g., those with supravalvar aortic stenosis (SVAS, MIM no. 18550) or Williams-Beuren syndrome (WBS, MIM no. 194050)] develop age-associated cardiovascular complications, including hypertension, stroke, and increased risk of sudden death at an earlier age (21, 39, 55). In addition, they have high rates of attention problems, anxiety, and chronic abdominal pain (2, 4, 34, 40), all features potentially attributable to their vascular disease. Individuals with WBS/SVAS display focal arterial stenosis in the setting of globally narrowed conducting arteries, hypertension, and increased arterial stiffness (21, 39). Present pharmacological therapies focus solely on reducing blood pressure (44, 50). On the basis of Poiseuille’s law, however,

| (1) |

where Q is the volumetric flow rate, R is the vessel radius, ΔP is the pressure drop along the vessel, η is dynamic fluid viscosity, and L is the vessel length; it is the radius of the vessel that exponentially drives the flow rate due to the dependence on R4. Consequently, pharmacotherapy aimed at improving arterial diameter may better preserve end-organ perfusion.

Eln+/− mice, like humans with SVAS and WBS, deposit less ELN and exhibit narrow arteries and increased arterial stiffness (1, 28). As a result, hypertension observed in Eln+/− mice may be a physiological adaptation that stents open the narrow, stiff vessels (9). Chronic treatment of Eln+/− mice with Ca2+ channel and angiotensin receptor blockers lowers systolic blood pressure (SBP) but does not alter large vessel biomechanics (13). Recently, however, it has been suggested that treatment with ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel openers, including minoxidil, increases ELN deposition in arteries (3, 47, 53). KATP channel openers, such as minoxidil, may therefore offer a novel intervention that both reduces hypertension and improves end-organ blood flow. In this study, we examine the impact of ELN insufficiency on cerebral blood flow (CBF) and the potential benefit of minoxidil for the treatment of ELN insufficiency-mediated vascular disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study approval.

All animals were maintained under identical conditions, in accordance with institutional guidelines, and all procedures were approved by either the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Washington University School of Medicine or the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Animals.

Eln+/− mice were first described by Li et al. (27). The original animal was backcrossed more than five times into C57Bl/6 mice. Four additional generations of backcrossing into C57Bl/6J mice were performed by these investigators, and single-nucleotide polymorphism genotyping was performed to assure the majority C57Bl/6J background (22). Animals used were the progeny of Eln+/+ [wild-type (WT)] × Eln+/− crosses and were housed together in sex-separated cages.

Drug administration.

Animals were segregated by cage to treatment and control groups. The treatment group received goal dosing of minoxidil at 20 mg·kg−1·day−1 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) diluted in drinking water from weaning to 3 mo of age. Water was changed 2 times/wk during the treatment period. Average dosing from six representative cages was noted to be 19.9 ± 3.6 mg·kg−1·day−1, but actual dosing per mouse could not be calculated. A subpopulation was treated with minoxidil, as described above, from weaning to 3 mo of age and then taken off treatment for 1 mo before analysis at 4 mo. For gene expression experiments, mice received minoxidil for 2 wk. Untreated control mice were given water ad libitum per routine and were aged to 3 or 4 mo as appropriate.

Systemic blood pressure and heart rate measurements.

The narrow diameter and tortuous course of Eln+/− vessels preclude the placement and continued function of indwelling radiotelemeters. Consequently, a method using sedated mice and a smaller, acutely placed catheter were used for this study. Mice were restrained on a heated holder to maintain body temperature, and anesthesia was induced with 2.5% inhaled isoflurane (Florane, Baxter, San Juan, Puerto Rico) and then reduced to 1.5%. Once a level plane of anesthesia was achieved, a pressure catheter (1.4-Fr, model SPR671, Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was inserted into the right carotid and advanced to the ascending aorta. Pressures were recorded using Chart 5 software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO). Each animal was allowed to acclimate for 5 min, at which time the anesthesia was reduced to 1% for an additional 5 min. Pressures were analyzed from the 6- to 9-min mark. Animals were monitored for discomfort or oversedation.

Pressure-diameter testing.

Ascending aortas (from the root to just distal to the innominate branch point) and left carotid arteries (from the transverse aorta to 6 mm up the common carotid) were dissected from WT and Eln+/− mice posteuthanasia. Vessels were mounted on a pressure arteriograph (Danish Myotechnology, Copenhagen, Denmark) in balanced physiological saline (130 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.6 mM CaCl2, 1.18 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 1.17 mM KH2PO4, 14.8 mM NaHCO3, 5.5 mM dextrose, and 0.026 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) at 37°C (all saline components from Sigma-Aldrich). All positions at which vessels were tied to the cannulae were internal to any branch sites and tested for leaks. Vessels were pressurized and longitudinally stretched three times to in vivo length (54) before data capture. Vessels were transilluminated under a microscope connected to a charge-coupled device camera and computerized measurement system (Myoview, Danish Myotechnology) to allow continuous recording of vessel diameters. Intravascular pressure was increased from 0 to 175 mmHg in 25-mmHg steps. At each step, the outer diameter (OD) of the vessel was measured and manually recorded. OD was used because of the previous finding by Faury et al. (8) that wall cross-sectional area remains constant in Eln+/− and WT vessels over the range of pressures tested, making OD a useful proxy for vessel size across conditions and genotypes. Distensibility can be calculated from the pressure diameter curves. Segmental distensibility (SD25) over a 25-mmHg interval = [ODHigher Pressure (H) − ODLower Pressure(L)]/OD(L)/25. Functional distensibility (FD) was calculated as the distensibility at average working pressure of the vessel as follows: FD = [(ODSBP − ODDBP)/ODDBP]/(SBP − DBP), where DBP is diastolic blood pressure.

Assessment of aortic stiffness and in vivo aortic diameter.

Aortic-arch pulse-wave velocity (PWV) was determined as previously described (45) using a modification of the transit-time method, implementing a Vevo 770 ultrasound system with an MS-400 transducer (VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada). Under isofluorane anesthesia (1.5%), the ascending aorta, aortic arch, and proximal portion of the descending aorta were imaged in one two-dimensional imaging plane from the right-side superior parasternal view. In some Eln+/− mice,, the entire arch could not be visualized in a single image plane because of the extreme tortuosity of the aorta. In these cases, the arch was imaged in two sections, the first from the aortic valve to the innominate artery and the second from the innominate artery to the proximal portion of the descending aorta, and the innominate artery was used to coregister these two images for accurate aortic arch length measurement. The pulse-wave Doppler sample volume was placed first near the aortic valve to record blood flow velocity in the proximal aorta and then promptly moved to the visualized portion of the descending aorta without changing the imaging plane to record blood flow velocity in the descending aorta. The curvilinear distance between the proximal and distal points of the aortic velocity interrogation (D2 − D1; in mm) was measured using the exact coordinates of the Doppler sample volumes. The time delay between the onset of flow velocity in the distal and proximal portions of the aorta (T2 − T1; in ms) was measured relative to the simultaneously recorded electrocardiogram signal. PWV was calculated as the ratio of (D2 − D1) to (T2 − T1) and expressed as meters per second.

For aortic dimensions, M-mode images were used to measure the inner diameter at the aortic arch. The M-mode line was placed perpendicular to the aortic walls, and systolic and diastolic diameters were measured for three cardiac cycles.

Desmosine and hydroxyproline content measurements.

A ninhydrin-based assay (48) was used to determine total protein. Briefly, 5 μl of the hydrolyzed sample were reacted at 85°C for 10 min with 100.0 μl ninhydrin (100 mM) dissolved in 75% ethylene glycol containing 2.5 mg/ml SnCl2 and 1.0 M sodium acetate (pH 5). Absorbance at 575 nm was determined using a Synergy H4 Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). Protein concentration in each sample was calculated by comparison with a standard curve generated using a calibration standard for protein hydrolysis (Pickering Laboratories, Mountain View, CA).

Hydroxyproline content was determined from a chloramine-T colorimetric assay (42). Briefly, duplicate samples were oxidized with 1.5 mg chloramine-T for 20 min at room temperature and then reacted for 20 min at 65°C with 20 mg p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde dissolved in propanol containing 20% perchoric acid. Absorbance was determined at 550 nm using a Synergy H4 Multi-Mode plate reader, and the amount of hydroxyproline was determined by comparison with a hydroxyproline standard curve. All reagents used in this assay were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Desmosine levels in tissue hydrolysates were quantified using a nonequilibrium, competitive ELISA (12). An aliquot of the sample was added to a desmosine-ovalbumin-coated well in a 96-well plate, and a 1:4,000 dilution of rabbit anti-desmosine antiserum (49) (gift from Dr. Barry Starcher, University of Texas Health Center) was added. After 1 h of incubation, nonbound antibody was removed by washing. Secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (NA934V, GE Health Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) was added for 1 h to detect primary antibody bound to the plate. Unbound secondary antibody-peroxidase was removed by washing. Peroxidase activity was quantified using SureBlue TMB peroxidase substrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). Absorbance at 650 nm was determined using a Synergy H4 Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek), and desmosine content was determined by extrapolation from a desmosine standard curve run on the same plate. The desmosine standards and desmosine-ovalbumin conjugate were obtained from Elastin Products (Owensville, MO). Blocking buffer, dilution buffer, wash solution, and the SureBlue TMB peroxidase substrate came from KPL. All procedures were performed at room temperature unless otherwise noted.

Heart and ventricular weight.

The heart was removed from the chest cavity, and the atria were trimmed. The heart was gently rolled on an absorbent surface to remove any intraventricular blood. Special care was taken to not crush the tissue and thereby disturb the interstitial fluid. Heart weight-to-body weight ratios were calculated to assess generalized hypertrophy.

Histology.

Segments of unloaded descending aorta, extending 2 mm past the left subclavian to 2 mm down, were dissected out and fixed in 1 ml of 10% buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 24 h and then progressively dehydrated in ethanol. Vessels were then embedded in paraffin, and cross-sectional rings were cut. Every 10th section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin to define landmarks. Measurements were made on sections obtained just distal to the branch of the left subclavian. To visualize ELN, sections were stained using Verhoeff van Gieson stain (k059, Poly Scientific R&D, Bay Shore, NY) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were scanned using the Hamamatsu NanoZoomer 2.0-RS digital slide scanner. Images were captured at ×10 with embedded scale using the Hamamatsu NDP.view2 viewing software (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). To quantify wall thickness, the preinstalled ruler in the NDP.view2 software was used. Both lamellar number and wall thickness were measured in each quadrant of 3 sections/vessel. For area measurements, three ×10 images were exported as .jpg files into ImageJ. In ImageJ, the global scale was set to micrometers using the NanoZoom-embedded scale, and images were converted to eight bit. Cross-sectional wall area was calculated by thresholding the area of interest until the tissue was saturated black (threshold = 92–95%) while the lumen remained white (unmeasured). To calculate the ELN-filled area, the threshold was set to 13–15% to turn the ELN area black and the lighter cellular area white for measurement. To identify the lumen, threshold settings were set to “dark background” so that the cross-sectional wall would be white (unmeasured) and the lumen would be black (measured). The magic wand tool was used to define boundaries. Cross-sectional wall-to-lumen area, ELN-to-cross-sectional wall area, and ELN area-to-lamellar number ratios were generated by dividing the two primary measurements. Median values for each vessel were used for statistical analysis.

Flow measurements.

Blood flow through the right common carotid artery was measured using TS420 perivascular flowmeter and a 0.5-mm PS-series probe (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY). Mice were anesthetized with 1–2% isoflurane in a 50:50 O2-N2 mixture and placed supine on a homeothermic heating plate (Physitemp TCAT-2LV, WPI, Sarasota, FL) with body temperature set to 37°C. The carotid artery was isolated from the carotid sheath through an anterior approach, taking care to preserve the right vagus nerve. The flow probe was placed around the artery without disturbing the natural course of the blood vessel, with saline used as the ultrasound-conductive medium. Isoflurane was then decreased to 1%, and, after a 5-min stabilization period, 5 min of data were recorded at 10 kHz using LabChart 7.9 data acquisition system (AD Instruments) connected to a personal computer. Average flow was calculated over the entire 5-min period. At the end of the data collection period, the mouse was deeply anesthetized and euthanized for tissue collection.

Arterial spin-labeling MRI.

All arterial spin-labeling (ASL)-MRI data were collected on a 4.7-T small animal MRI system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) using a home-built volume transmit/surface receive coil configuration. A Flow-Sensitive Alternating Inversion Recovery (FAIR) (18, 23) sequence was used to measure cortical perfusion in the brains of Eln+/− and Eln WT mice. Briefly, the FAIR-type ASL experiment consists of two data readout conditions in which either 1) a slice-selective adiabatic inversion radiofrequency (RF) pulse precedes the fast spin-echo data readout sequence, a scheme that is sensitive to flowing spins, or 2) a nonslice-selective adiabatic inversion RF pulse precedes the fast spin-echo readout sequence, a scheme that is insensitive to flowing spins (control). The difference between the slice-selective and nonslice-selective conditions (ΔM) reports on tissue perfusion in arbitrary units. The time between the inversion pulses and the readout (TI) was 1,500 ms. The number of transients (averages; NT) = 32; repetition time (TR) = 7,500 ms, and total scan time (for both slice-selective and nonslice-selective conditions) = 64.5 min. Imaging parameters specific to the fast spin-echo readout were as follows: echo time (TE) = 6.4 ms, echo train length (ETL) = 8, k-zero = 1, effective echo time (TE × k-zero) = 6.4 ms, matrix = 64 × 64, and field of view (FOV) = 16 × 16 mm2.

A voxel-wise estimate of the apparent tissue longitudinal relaxation constant (R1) and equilibrium magnetization (M0) is required to convert the ΔM map to a quantitative map of perfusion in absolute units. To this end, longitudinal relaxation data were collected via a fast spin-echo, inversion recovery experiment (16 TI values between 20 and 4,500 ms), and voxel-wise maps of R1 and M0 were calculated by fitting the data to a “monoexponential plus a constant” model of magnetization recovery.

From the acquired slice-selective and nonslice-selective imaging data and calculated R1 maps, tissue perfusion (CBF) was calculated on a voxel-wise basis according to Refs. 19 and 38 as follows:

| (2) |

in which α0 is the fraction of equilibrium-polarized magnetization that gets inverted, λ is the blood-tissue water partitioning coefficient (0.9 ml/g) (15), R1,a is the longitudinal relaxation rate constant of arterial blood at 4.7 T (herein assumed to be 1.7 s−1) (20), and τ is the difference between TR and TI (6,000 ms). X(TR) is the effective degree of inversion, given as follows:

| (3) |

where N is the number of nonslice-selective inversion repetitions.

For anatomic reference, T2-weighted, fast spin-echo images were acquired as follows: TE = 6.4 ms, ETL = 8, k-zero = 4, TE × k-zero = 12.5 ms, matrix = 64 × 64, FOV = 16 × 16 mm2, TR = 2,000 ms, and NT = 16.

RNA preparation and sequencing.

Aortic tissue from the left subclavian to the diaphragm was collected from three groups of 3-mo-old Eln+/− mice (n = 4 each). One group received regular drinking water. A second group received minoxidil in drinking water for 2 wk before euthanization. The final group received minoxidil in drinking water for 2 wk and then received drug-free drinking water for 1 wk before tissue harvest. After collection, tissues were frozen in RNA Later until all tissues were available and could be processed for RNA as a group. RNA extraction was done by the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quality control testing showed all samples to be good, and all samples underwent library preparation using an Illumina TruSeq Standard Total RNA sample preparation kit. cDNA libraries were validated by Illumina Miseq, and DNA sequencing was performed in the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. Quality of the paired-end Hi-Seq reads of all samples were assessed with fastqc package from the website (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). The RNA-Seq will be publicly available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ with GEO Accession ID GSE110296.

RNA sequence analysis.

Reads were aligned to mouse genome M13 using STAR(5) on computational resources of the National Institutes of Health HPC Biowulf cluster (https://hpc.nih.gov/). An average of 71 million paired end reads mapped to mouse Gencode genes (release M13) were summarized by featureCounts (29). The total counts of reads across samples were normalized by the DESeq2 package (30). In total, 19,980 genes with 10 or more reads in all samples were selected, and log2-transformed reads were used for downstream analysis. Treatment effects of the samples were qualitatively assessed by the first few principal components of the expression data. A one-way ANOVA model was then used and followed with post hoc t-tests between any two groups for each gene in three separate analyses. Genes with 1.5-fold change in expression between two groups and with a false discovery rate of <10% were considered differentially expressed and selected for further investigation. Differentially expressed genes were grouped into clusters based on their expression pattern across treatment conditions (clusters 1–4). Enrichment of the selected genes in canonical pathways in MSigDB was assessed at the http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/login.jsp;jsessionid=7EA22FCBA32BBEF6212F40B04DE2139A website. JMP 13 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R software (https://cran.r-project.org) were used in data analysis. G:profiler (http://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/) was also used for identifying relevant Gene Ontology (GO) terms associated with genes within the Naba_matrisome pathway for each cluster.

Statistics.

All statistics were performed using Prism 7.0 statistical software. Blood pressures, desmosine/hydroxyproline analysis, FD, histological quantification, PWV, carotid flow testing, echo-based aortic diameter measures, and cortical ASL measures in untreated WT and untreated and treated 3-mo-old Eln+/− mice were compared using one-way ANOVA. Tukey’s multiple-comparisons testing was used. For pressure-diameter and distensibility testing, two-way ANOVA with repeated measures for increasing pressure was used. Tukey’s multiple-comparisons testing was used. In the experiments comparing 3- and 4-mo treated and untreated Eln+/− animals, ANOVA testing was performed as above. However, in this case, Dunnett’s multiple-comparison testing was done specifically to compare 4-mo treated mice to the remaining groups. Likewise, in experiments evaluating differences among untreated, 2-mo treated, and 2-wk treated Eln+/− mice, Dunnett’s multiple-comparison testing was done specifically to compare the 2-wk treated mice to the remaining groups. For the MRI-ASL studies, t-tests were used for each independent brain region and in testing for drug treatment effects in the cortex.

RESULTS

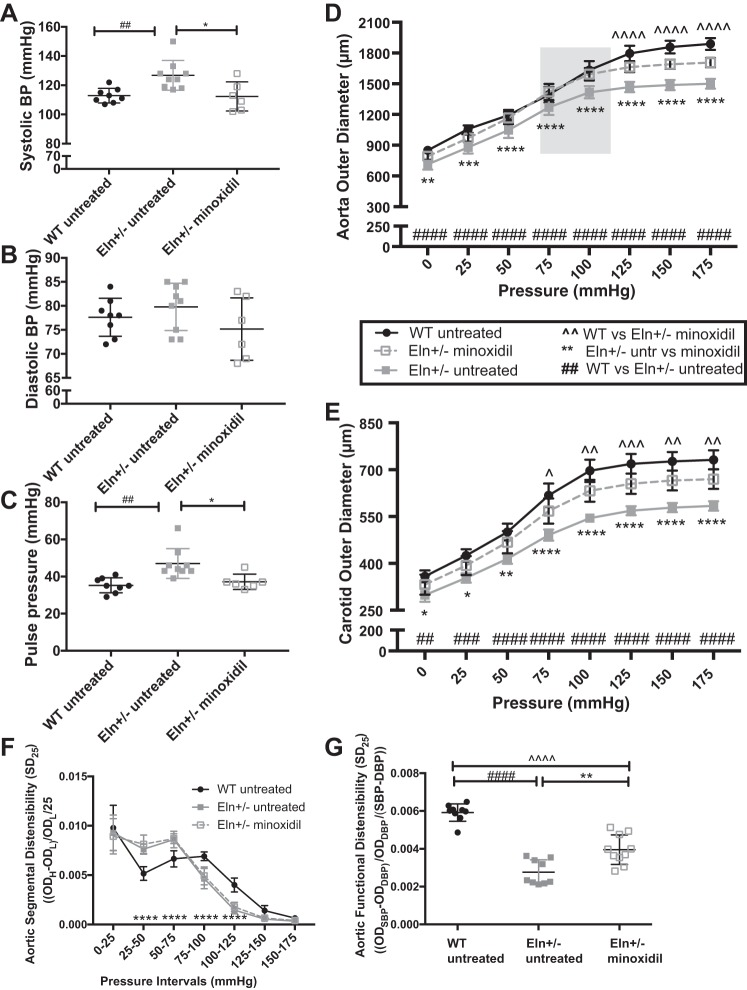

Treatment from weaning with minoxidil normalizes SBP and pulse pressure.

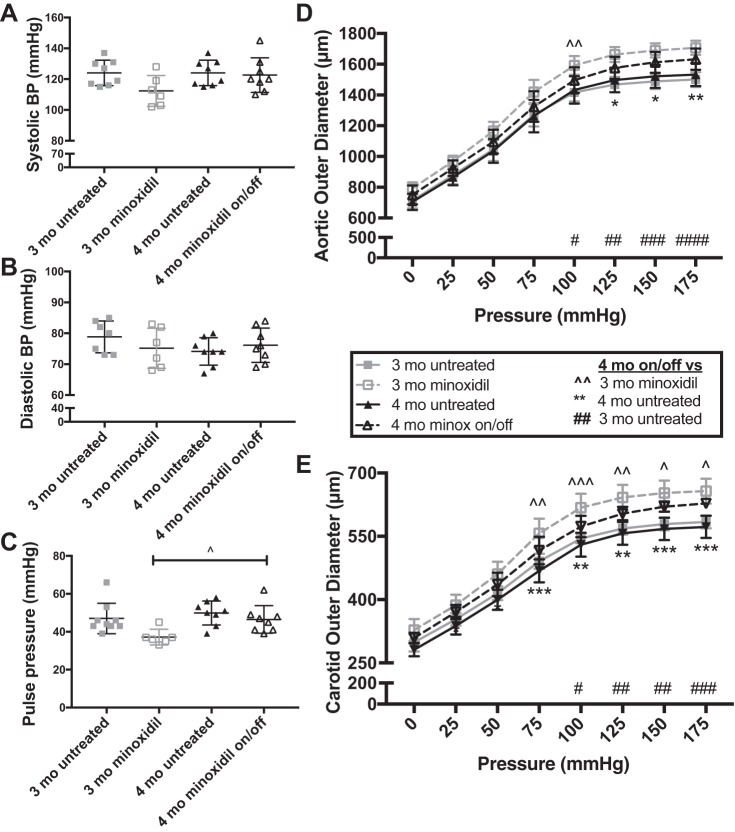

Mice were treated with minoxidil in drinking water from weaning until 3 mo of age, when blood pressure was assessed (Fig. 1, A–C). Data from male mice are shown. Treatment of female mice showed similar effects (data not shown). One-way ANOVA showed a difference among groups for SBP (P < 0.01; Fig. 1A) and pulse pressure (PP; P < 0.01; Fig. 1C). No statistically significant differences were seen for DBP (Fig. 1B). Multiple-comparisons testing showed lower SBP in minoxidil-treated Eln+/− mice compared with untreated Eln+/− mice (P < 0.05). For PP, treated Eln+/− mice had lower pressures than untreated Eln+/− mice (P < 0.05). As expected, SBP and PP were higher in untreated Eln+/− mice than in WT mice (P < 0.01). The remaining comparisons were not significant. Heart rate and the heart weight-to-body weight ratio were not different as a result of minoxidil treatment (data not shown). Pericardial effusion was not noted in treated mice.

Fig. 1.

Minoxidil decreases blood pressure (BP) and increases vessel diameter in elastin (Eln)+/− mice. Mice received minoxidil in drinking water from weaning to 3 mo of age. A–C: systolic BP (SBP; A), diastolic BP (DBP; B), and pulse pressure (C; by one-way ANOVA). D and E: pressure-diameter curves in the aorta (D) and carotid (E) arteries (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA). F and G: aortic segmental distensibility (SD25; F) and functional distensibility (FD; G) at average BP (by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA). In A−G, wild-type (WT) mice are shown as black circles and Eln+/− mice are shown as gray squares. Minoxidil-treated Eln+/− mice are shown as open squares. Means and standard deviations are shown as whiskers underlying the data points. On the pressure-diameter curves, untreated animals [WT (black) and Eln+/− (gray)] are shown as solid lines and minoxidil-treated Eln+/− animals are shown as dashed lines. Comparisons (Tukey’s) among individual groups are shown. ^^Minoxidil-treated Eln+/− vs. untreated WT comparisons; **minoxidil-treated Eln+/− vs. untreated Eln+/− comparisons; ##untreated WT vs. untreated Eln+/− tests; *,^P < 0.05, **,^^,##P < 0.01, ***,^^^,###P < 0.001, and ****,^^^^,####P < 0.0001. Treatment with minoxidil reduced SBP and pulse pressure and increased aortic and carotid diameters at multiple pressures. SD25 in the aorta of minoxidil-treated Eln+/− mice was similar to untreated Eln+/− mice, but FD was intermediate. The remaining comparisons were not significant. The gray box represents the average aortic BP range of minoxidil-treated Eln+/− mice (112/74 mmHg). OD, outer diameter.

Treatment from weaning with minoxidil normalizes conducting artery diameter at physiological pressures.

Vessels [the aorta (Fig. 1D) and left common carotid (Fig. 1E)] were removed and evaluated on a pressure myograph. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA showed significant differences with increasing pressure (P < 0.0001) and among groups (P < 0.0001) in both vessels. There was also a highly significant interactive effect (P < 0.0001). Multiple-comparisons testing showed that the aortic diameter of the treated Eln+/− cohort was larger than that of the untreated Eln+/− cohort and overlapped with the tracing of the untreated WT cohort over the working pressures of the vessel (highlighted). Findings were similar in the carotid artery (Fig. 1E). SD25 in the aorta did not differ between treated and untreated Eln+/− mice (Fig. 1F). However, aortic FD, calculated as the fractional change in aortic diameter over the average working pressure for each group, was lower in untreated Eln+/− mice than in WT mice (Fig. 1G). Minoxidil treatment improved, but did not completely restore, aortic FD in Eln+/− mice (Fig. 1G). A similar trend was seen in the carotid but did not reach statistical significance (data not shown).

Minoxidil increases ELN content and induces arterial remodeling.

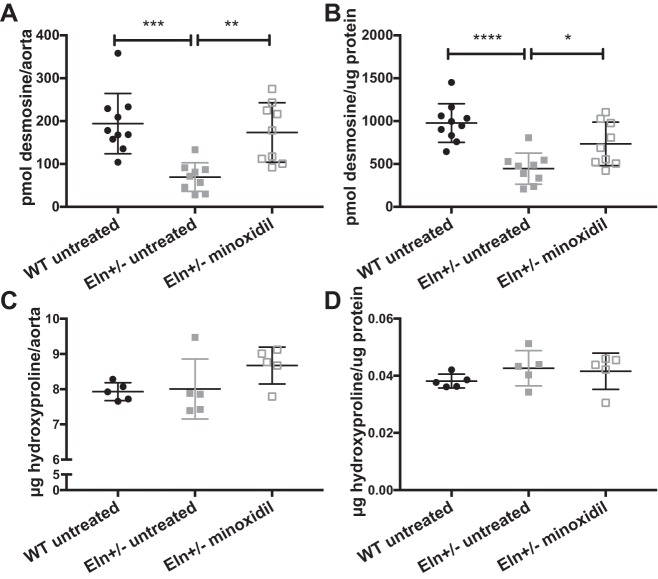

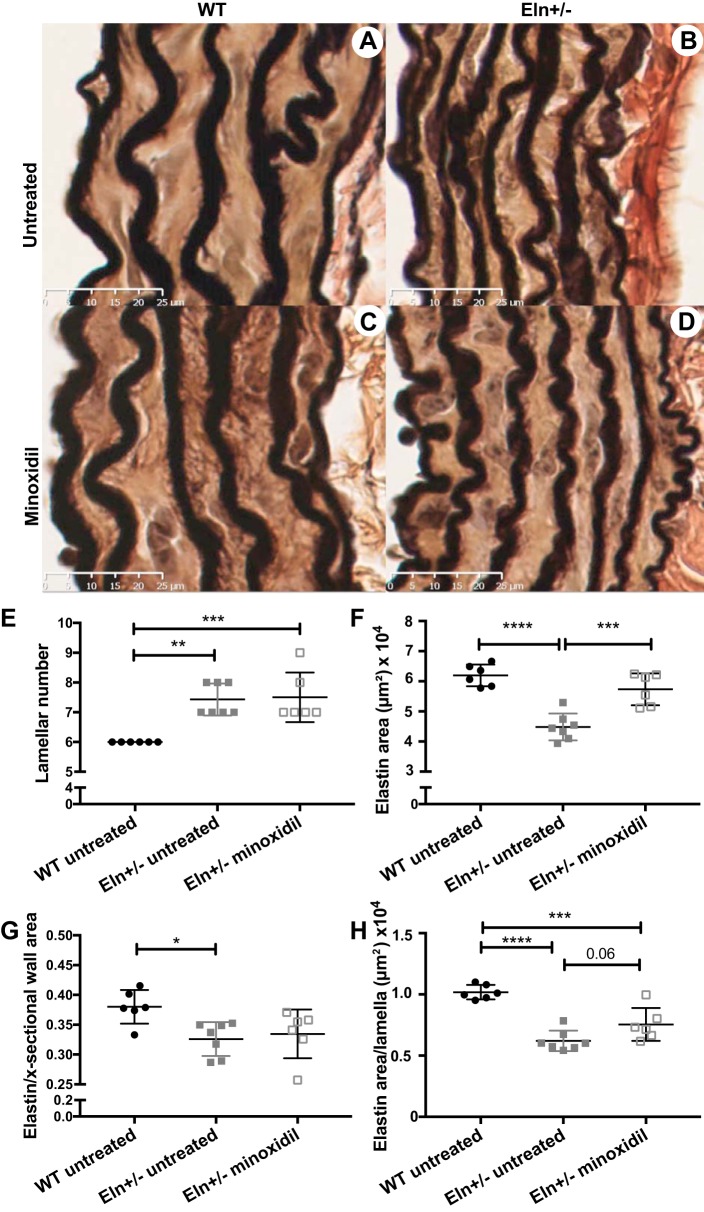

Previous studies in rats have suggested that minoxidil leads to increased deposition of ELN into the extracellular matrix (ECM) of conducting arteries (47). To quantify the amount of ELN and collagen, we hydrolyzed ascending aortas from each group and quantified the amount of desmosine, an ELN-specific cross link, and hydroxyproline, an amino acid commonly seen in collagen. When normalized to aortic segment (root to just proximal to the innominate branch point), highly significant differences were seen for desmosine among groups (P < 0.001). Multiple-comparisons testing shows a statistically significant increase in desmosine in the treated Eln+/− group relative to the untreated Eln+/− group (P < 0.01; Fig. 2A). Hydroxyproline in aortic segments was not statistically different among groups (Fig. 2C). To account for the increase in vessel caliber seen on pressure-diameter testing in the treated cohorts, desmosine and hydroxyproline were also normalized to total protein in the vessel. Total protein was higher in the treated groups, but, with this normalization, desmosine-to-protein ratios continue to show differences between groups (P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA). Multiple-comparisons testing of the protein-normalized values show increased (albeit to a lesser extent) desmosine in the treated Eln+/− group compared with the untreated Eln+/− group (P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). As expected, in both normalization schemes, untreated Eln+/− aortas had less desmosine compared with WT aortas (P < 0.001 when normalized to the aortic segment and P < 0.0001 when normalized to total protein). Hydroxyproline concentrations were also insignificant when normalized to total protein (Fig. 2D). Examples of histological sections of unloaded descending aortas are shown in Fig. 3, A–D. Aortas from untreated Eln+/− mice had an increased number of elastic lamellae relative to WT mice (P < 0.01; Fig. 3E) but the lamellar number was unchanged by treatment with minoxidil. At the same time, the total area stained with ELN stain (Fig. 3F) was lower in the untreated Eln+/− group relative to the WT group (P < 0.0001) but increased in the treated Eln+/− group (P < 0.001). When normalized to the wall cross-sectional area of the vessel (Fig. 3G), a difference remained between WT and untreated Eln+/− groups (P < 0.05) but treatment did not improve the ratio. When the total area of ELN was divided by lamellar number, the quantity of ELN per lamella trended higher with treatment (P = 0.06).

Fig. 2.

Minoxidil increases elastin (ELN) but not collagen in Eln+/− aortas. Mice received minoxidil in drinking water from weaning to 3 mo of age. Desmosine (ELN; A and B) and hydroxyproline (collagen; C and D) content are shown relative to the ascending aortic segment (A and C) and total protein (B and D). Genotype and treatment status are shown below each graph (one-way ANOVA). Multiple comparisons (Tukey’s) are shown. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Desmosine was higher in wild-type (WT) untreated and minoxidil-treated Eln+/− mice than in untreated Eln+/− mice regardless of normalization, although the differences were reduced when normalized to total protein. Collagen content, as assessed by hydroxyproline level, showed no differences among the groups tested. Means and standard deviations are shown by error bars.

Fig. 3.

Elastin (ELN) changes in minoxidil-treated vessels. A−D: histological sections of unloaded descending aortas from untreated wild-type (WT; A), untreated Eln+/− (B), minoxidil-treated WT (C), and minoxidil-treated Eln+/−(D) mice are shown stained with elastin van Gieson stain. ELN is dark. E: lamellar number for the descending aorta. F: total area that stained with the ELN stain. G: ELN-stained area as a fraction of the total wall area. H: per lamella ELN area. Genotype and treatment status are shown below each graph (one-way ANOVA). Multiple comparisons (Tukey’s) are shown. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. All other comparisons were not significant. Means and standard deviations are shown by error bars.

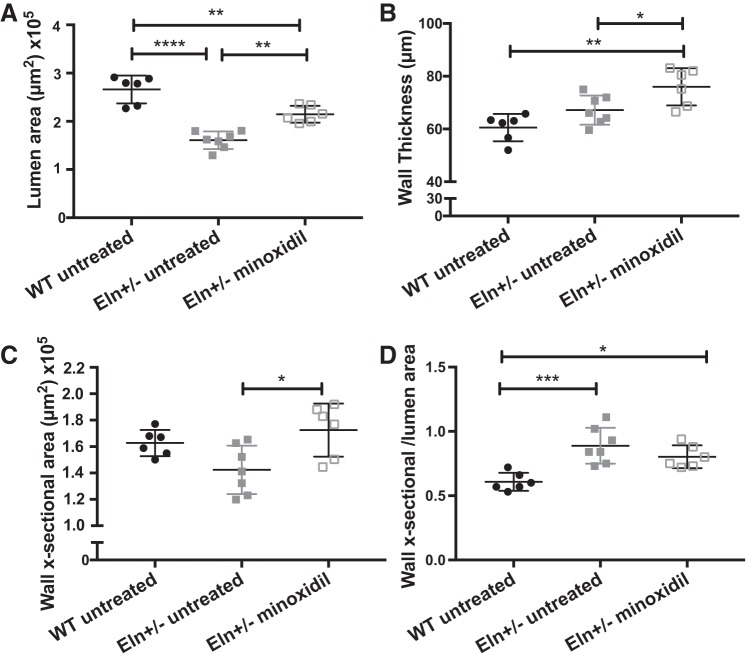

In addition to increasing elastic content, minoxidil also changes vessel structure. Similar to the data obtained from pressure myography, histological assessment of unloaded vessels showed that the lumen area was smaller in untreated Eln+/− mice than in WT mice (P < 0.0001; Fig. 4A). Minoxidil treatment increased the Eln+/− lumen size (P < 0.01) but it did not reach WT levels at unloaded pressures. At the same time, minoxidil-treated vessels had increased wall thickness relative to either WT (P < 0.01) or untreated Eln+/− aortas (P < 0.05). Because Eln+/− mice have a smaller circumference, the wall cross-sectional areas of WT vessels and untreated Eln+/− vessels were not statistically different (Fig. 4C), but, by increasing both lumen size and wall thickness, minoxidil increased the total wall area of the treated Eln+/− group relative to the untreated Eln+/− group (P < 0.05). The wall cross-sectional area-to-lumen area ratio (Fig. 4D) was higher in Eln+/− mice than in WT mice (P < 0.001) and was not rescued by minoxidil treatment. Taken together, these findings suggest that minoxidil leads to outward remodeling and growth of Eln+/− conducting arteries, impacting both lumen size and wall thickness. ELN content increased but was largely a function of vessel growth, with only a small excess amount of desmosine seen in the higher-powered cross-link analysis and no statistically significant increase in the histological analysis.

Fig. 4.

Minoxidil induces vessel remodeling and growth. A: lumen area from wild-type (WT), untreated elastin (Eln)+/−, and minoxidil-treated Eln+/− mice. B: wall thickness. C: wall cross-sectional area. D: wall cross-sectional-to-lumen area ratio. Genotype and treatment status are shown below each graph (one-way ANOVA). Multiple comparisons (Tukey’s) are shown. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. All other comparisons were not significant. Means and standard deviations are shown by error bars.

The improvement in vascular diameter persists when treated mice are removed from minoxidil.

If deposited in a physiologically relevant way, ELN is remarkably stable, with a presumed half-life of ~70 yr (46). To determine whether the changes induced by minoxidil treatment would persist, we treated Eln+/− mice with minoxidil from weaning to 3 mo of age and then removed the drug until 4 mo of age and compared these results with the previously described 3-mo-old Eln+/− mice and new 4-mo-old untreated Eln+/− mice to assess for normal growth with aging (Fig. 5). No significant differences were found for SBP or DBP, although SBP trended higher in 4-mo-old mice treated and removed from drug than in 3-mo-old mice presently on minoxidil. PP differences were significant by one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05; Fig. 3C). Multiple-comparisons testing comparing the treated 4-mo-old group (treated between weaning and 3 mo of age and then removed from drug until 4 mo) with the other groups showed that PP was higher in the 4-mo-old group removed from drug than in the 3-mo-old group maintained on minoxidil (P < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Vessels from elastin (Eln)+/− mice removed from minoxidil remain larger than those from untreated animals. Eln+/− mice received minoxidil in drinking water from weaning to 3 mo, as shown in Fig. 1. Additional mice received the drug until 3 mo and water only (no drug) from ages of 3 to 4 mo (Eln+/− minoxidil on/off). Mice were euthanized at 4 mo along with untreated 4-mo control mice. A−C: systolic blood pressure (BP; A), diastolic BP (B), and pulse pressure (C; by two-way ANOVA). D and E: pressure-diameter curves in the aorta (D) and carotid (E) arteries (by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA). 3-mo-old Eln+/−mice are shown by gray symbols, 4-mo-old Eln+/− mice are shown as black symbols; untreated animals are shown as solid lines, and minoxidil-treated animals are shown by dashed lines and open symbols. Multiple testing results (Dunnett’s) comparing the 4-mo Eln+/− minoxidil on/off group to the remaining three groups are shown. D and E: P values comparing 4-mo Eln+/− minoxidil on/off mice with 3-mo minoxidil-treated mice are denoted as ^^; P values with 3-mo untreated mice are denoted as ##. P values comparing 4-mo minoxidil on/off Eln+/− and 4-mo untreated Eln+/− mice are denoted as **. * (or ^ or #) P < 0.05, ** (or ^^ or ##) P < 0.01, and *** (or ^^^ or ###) P < 0.001. The remaining comparisons were not significant. While BP reverted to untreated levels off drug, 4-mo-old treated then off Eln+/− mice trended between treated 3-mo-old Eln+/− and untreated mice, with varying degrees of significance. Means and standard deviations are shown by error bars.

For pressure-diameter experiments, repeated-measures two-way ANOVA showed highly significant differences in diameter with increasing pressure (P < 0.0001) and among treatment groups (P < 0.0001) in both the aorta (Fig. 3D) and carotid artery (Fig. 3E). There was also a highly significant interactive effect (P < 0.0001). Multiple-comparisons testing between Eln+/− mice treated from weaning to 3 mo and off for 1 mo (4-mo minoxidil-treated/off) and the other subgroups of mice showed that the aortic diameter of 4-mo-treated/off Eln+/− mice was larger than 3-mo untreated Eln+/− mice at all pressures except 0 mmHg. It was not significantly different from 3-mo treated mice at nearly all pressures. Compared with 4-mo untreated mice, however, it trended larger throughout but only reached significance at the higher pressures. In the carotid, however, 4-mo treated/off mice were statistically larger than 4-mo untreated mice over the full range of pressures (except 0 mmHg), whereas they had reduced size compared with 3-mo treated Eln+/− mice at pressures over 75 mmHg. They remained statistically larger than untreated 3-mo-old Eln+/− mice over the majority of this window.

Minoxidil normalizes in vivo aortic diameter, arterial stiffness, and carotid blood flow in Eln+/− mice.

Like the ex vivo pressure-diameter evaluation and histological assessment of unpressurized vessels, in vivo assessment of ascending aortic lumen diameter by M-mode ultrasound revealed differences in aortic caliber among the groups tested (P < 0.01 at systolic pressure and P < 0.001 at diastolic pressure by one-way ANOVA; Fig. 6A). Multiple-comparisons testing revealed a smaller luminal diameter in untreated Eln+/− mice compared with WT mice (P < 0.05). No differences between untreated Eln+/− and WT mice were seen at diastolic pressure. Treatment with minoxidil increased both diameters (P < 0.01 at systolic pressure and P < 0.001 at diastolic pressure; Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Minoxidil normalizes in vivo diameter, pulse wave velocity, and carotid blood flow in chronically treated elastin (Eln)+/− mice. Mice received minoxidil in drinking water from weaning to 3 mo of age. A−C: in vivo lumen diameter (systolic and diastolic; A), pulse wave velocity (B), and carotid artery Doppler flow (C) for wild-type (WT) mice (black circles) and Eln+/− mice (gray squares) treated with water (closed symbols) or minoxidil (open symbols). One-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons are shown. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. In each case, minoxidil treatment returned abnormal Eln+/− values to near WT levels. D: carotid flow for all vessels tested as a function of carotid radius to the fourth power (R4) at 100 mmHg. Means and standard deviations are shown by error bars in A–C.

PWV is a noninvasive means of measuring in vivo arterial stiffness, with higher PWV being a surrogate for functionally increased stiffness. As in humans with WBS, 3-mo-old mice with ELN insufficiency had higher PWV than WT control mice (P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA; Fig. 6B) with multiple-comparisons testing showing WT versus untreated Eln+/− mice (P < 0.0001). Minoxidil treatment of Eln+/− mice, however, led to a statistically significant reduction of PWV relative to untreated Eln+/− mice (P < 0.001). There was no difference between treated Eln+/− and WT groups.

To evaluate the impact of ELN insufficiency and treatment on blood flow, we examined flow in the right carotid artery using an ultrasonic flow probe. At baseline, 3-mo-old Eln+/− carotids demonstrated 29% reduced blood flow relative to WT carotids (P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA, with post hoc analysis comparing WT with untreated Eln+/− mice, P < 0.01; Fig. 6C). Treatment with minoxidil, however, increased flow in Eln+/− vessels relative to untreated Eln+/− vessels (P < 0.05) and returned it to WT values, reflecting the combined effect of lowered pressure (decreases flow) and the much more substantial impact of larger arterial diameter on increasing flow. Correlation analysis showed reasonable correlation (r = 0.48) of carotid R4 with blood flow through that vessel regardless of genotype/treatment status (Fig. 6D).

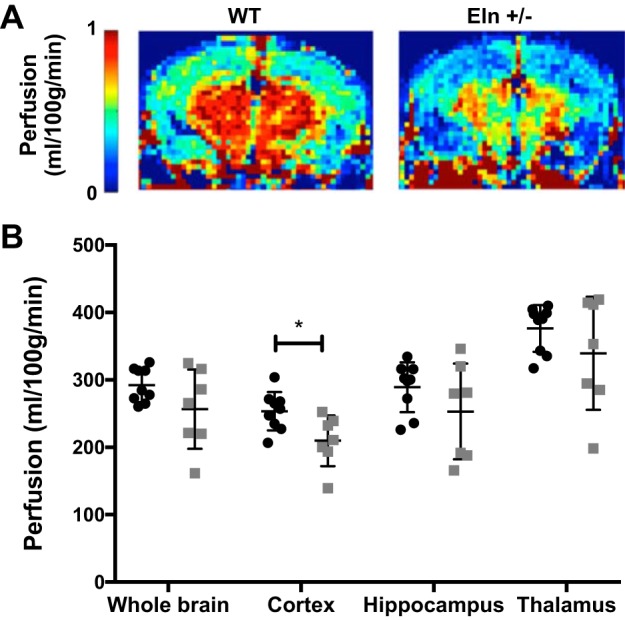

Minoxidil restores CBF in Eln+/− mice.

Given the finding of reduced blood flow through the carotids in Eln+/− mice, we sought to evaluate perfusion of the brain. ASL-MRI is a noninvasive method of measuring the perfusion of 1H protons (water in blood) into tissue. Here, we used ASL-MRI to map brain perfusion in Eln+/− and WT mice. ASL-MRI perfusion maps revealed suppressed CBF in Eln+/− mice compared with their WT counterparts (Fig. 7A), particularly in the cortex, in which perfusion was reduced from 251 ml·100 g−1·min−1 in WT mice to 209 ml·100 g−1·min−1 in Eln+/− mice, a −17% difference (P < 0.05; Fig. 7B). Whole brain, hippocampal, and thalamic perfusion measures in the Eln+/− cohort were not statistically different from the WT cohort, although they each trended lower than those of their WT counterparts.

Fig. 7.

Elastin (ELN) insufficiency decreases brain perfusion in mice. A and B: representative perfusion maps for wild-type (WT) and Eln+/− cohorts (A) along with plots of arterial spin-labeling MRI-measured perfusion in the whole brain, cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus regions of interest (ROIs; B). Perfusion maps suggested reduced global perfusion in the Eln+/− cohort (light gray) compared with the WT cohort (black), particularly in the cortex, where perfusion was reduced from 251 ml·100 g−1·min−1 in WT mice to 209 ml·100 g−1·min−1 in Eln+/− mice (P < 0.05 by t-test). No group differences were seen in the whole brain, hippocampal, and thalamic ROI analyses, although the perfusion in the Eln+/− cohort trended lower in these regions compared with the WT cohort. For each t-test, *P < 0.05. Means and standard deviations are also shown.

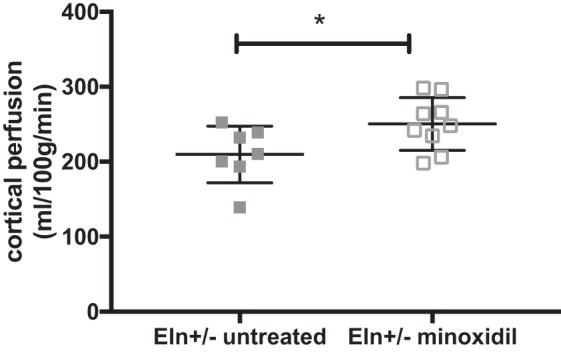

Treatment with minoxidil, however, increases cortical perfusion in Eln+/− mice (Fig. 8). Cortical perfusion increased from 209 ml·100 g−1·min−1 in untreated Eln+/− mice to 250 ml·100 g−1·min−1 in minoxidil-treated Eln+/− mice (Fig. 8). Similar values were seen for untreated WT mice (Fig. 7). Only cortical perfusion was evaluated because it was significantly different from WT mice in the untreated cohort.

Fig. 8.

Minoxidil increases cortical perfusion in elastin (Eln)+/− mice. Mice were treated from weaning to 3 mo of age with minoxidil in drinking water. Minoxidil treatment increased cortical perfusion in Eln+/− mice. Cortical perfusion increased from 209 ml·100 g−1·min−1 in untreated Eln+/− mice (gray filled squaress) to 250 ml·100 g−1·min−1 in minoxidil-treated Eln+/− mice (gray open squares). *P < 0.05 by t-test. Means and standard deviations are also shown.

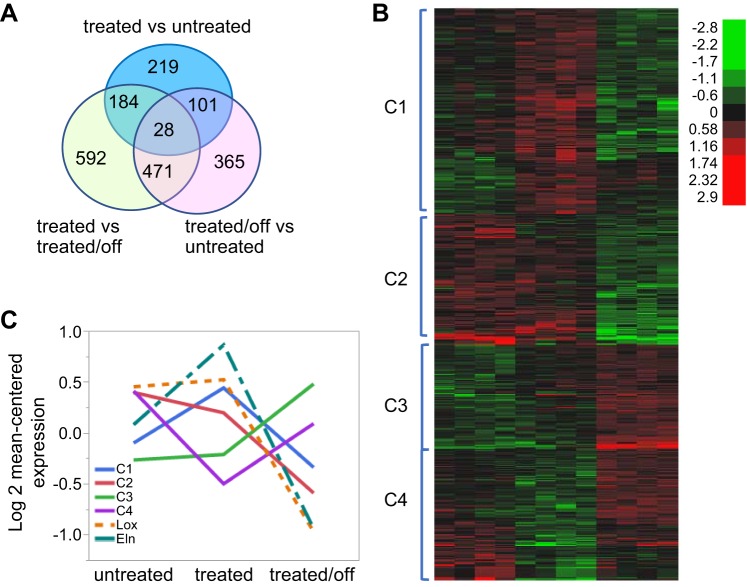

Minoxidil alters vascular mechanics through changes in ECM gene expression.

Minoxidil is a KATP channel opener and acts primarily to induce vascular smooth muscle relaxation and dilation (16). How treatment with this drug leads to long-term remodeling of the vasculature is unknown. To assess this, we sought to look at changes in gene expression induced by chronic minoxidil treatment. Samples were collected from three groups: untreated mice, mice on minoxidil for 2 wk, and mice on the drug for 2 wk and off the drug for 1 wk. The 2-wk treatment period was chosen to assess a midexposure window, avoiding the acute vasodilation phase and the late exposure time point when most of the vessel remodeling has already been accomplished (Fig. 9). Groups (n = 4 mice/group, untreated, treated, and treated/off) were well clustered in first two principal components (data not shown). In total, 1,960 genes were identified from 3 separate comparisons of untreated versus treated, untreated versus treated/off, and treated versus treated/off groups with 1.5-fold change and a 0.1 false discovery rate from post hoc t-test. Details about the number of selected genes in each comparison are shown in the Venn diagram in Fig. 10A (some genes were differentially expressed between members of more than 1 treatment pair). Expression values for the 1,960 differentially regulated genes in the 12 samples are shown in Supplemental Table S1 (Supplemental Material for this article is available at the American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology website). Hierarchical clustering of the genes in the samples in Fig. 10B visually suggested 4 clustering patterns with 703, 445, 597, and 215 genes from clusters 1 to 4, respectively.

Fig. 9.

Minoxidil treatment of elastin (Eln)+/− mice for 2 wk shows vessel size intermediate between untreated and 2-mo-treated mice. Eln+/− mice received minoxidil in drinking water for 2 wk or 2 mo. Untreated mice are also shown. A: systolic blood pressure (BP). B and C: pressure-diameter curves in the aorta (B) and carotid (C). Untreated Eln+/− mice and Eln+/− mice treated with minoxidil for 2 mo are shown using black or gray solid lines, respectively, and filled boxes. These are the same data used in Fig. 1. Four mice treated with minoxidil for 2 wk are shown using gray dashed lines and open gray boxes. Means and standard deviations are shown as whiskers underlying the data points. For A–C, one-way ANOVA demonstrated P < 0.05 or better. Dunnett’s multiple comparisons were performed comparing the 2-wk treated Eln+/− group with the other treatment groups. P values comparing 2-wk Eln+/− minoxidil-treated with 2-mo-minoxidil-treated mice are denoted with ^, and P values with untreated mice are denoted with *. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***,^^^P < 0.001, and ****,^^^^P < 0.0001. The remaining comparisons were not significant.

Fig. 10.

Differentially expressed genes with minoxidil treatment and discontinuation. A: Venn diagram with the numbers of differentially expressed genes for each comparison. All differentially expressed genes with expression differences of at least 1.5-fold with a false discovery rate of 0.1 between any two of the treatment groups were plotted by heat map. The four main subgroups [clusters 1−4 (C1–4)] are shown in B. C: log2 mean-centered expression of genes within a given cluster in untreated elastin (Eln)+/− mice, mice treated with minoxidil for 2 wk, and mice treated for 2 wk and then removed from the drug for 1 wk. The expression profiles for Eln and lysyl oxidase (Lox) are shown superimposed on the cluster data (dashed lines).

Enrichment of the genes in clusters 1−4 in canonical pathways in MSigDB are shown in Table 1 (top 5 enriched pathways per cluster; a complete list of enriched pathways can be found in Supplemental Tables S2–S5). Enrichment for matrix-related proteins is noted for each cluster. In particular, the Naba_matrisome (35) pathway was detected as one of the two most highly enriched pathways in all four clusters.

Table 1.

Pathway enrichment by cluster of differentially expressed genes

| Cluster | Pathway | Description | Number of Genes in Overlap | P Value | False Discovery Rate q Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 (703 genes) | Naba_matrisome (1028)† | Ensemble of genes encoding the ECM and ECM-associated proteins | 58 | 5.62 × 10−28 | 7.46 × 10−25 |

| Naba_core_matrisome (275)* | Ensemble of genes encoding the core ECM, including ECM glycoproteins, collagens, and proteoglycans | 34 | 1.17 × 10−27 | 7.79 × 10−25 | |

| Kegg_ECM_receptor_interaction (84)* | ECM receptor interaction | 21 | 2.76 × 10−24 | 1.22 × 10−21 | |

| NABA_ECM_glycoproteins (196)* | Genes involving structural ECM glycoproteins | 26 | 3.18 × 10−22 | 1.06 × 10−19 | |

| Kegg_focal_adhesion (201)* | Focal adhesion | 24 | 1.62 × 10−19 | 4.31 × 10−17 | |

| Cluster 2 (445 genes) | Reactome_ immune_system (933) | Genes involved in the immune system | 28 | 5.41 × 10−13 | 7.18 × 10−10 |

| Naba_matrisome (1028)† | Ensemble of genes encoding the ECM and ECM-associated proteins | 26 | 1.59 × 10−10 | 1.06 × 10−7 | |

| Reactome_interferon_alpha beta signaling (64) | Genes involved in interferon-α/β signaling | 8 | 2.64 × 10−9 | 1.17 × 10−6 | |

| KEGG_MAPK_signaling (267) | MAPK signaling pathway | 13 | 3.99 × 10−9 | 1.22 × 10−6 | |

| PID_AP1_pathway (70) | Activator protein-1 transcription factor network | 8 | 5.48 × 10−9 | 1.22 × 10−6 | |

| Cluster 3 (597 genes) | Naba_matrisome (1028)† | Ensemble of genes encoding the ECM and ECM-associated proteins | 33 | 1.26 × 10−10 | 1.67 × 10−7 |

| Reactome_biological oxidations (139) | Genes involved in biological oxidations | 12 | 3.35 × 10−9 | 2.22 × 10−6 | |

| Reactome_phase 1 functionalization of compounds (70) | Genes involved with phase 1 functionalization of compounds | 9 | 9.37 × 10−9 | 4.15 × 10−6 | |

| Naba_core_matrisome (275)* | Ensemble of genes encoding the core ECM, including ECM glycoproteins, collagens, and proteoglycans | 15 | 2.04 × 10−8 | 6.79 × 10−6 | |

| Reactome_potassium channels (98) | Genes involved with K+ channels | 9 | 1.84 × 10−7 | 4.47 × 10−5 | |

| Cluster 4 (215 genes) | Naba_matrisome associated (753)* | Ensemble of genes encoding ECM-associated proteins, including ECM-affiliated, ECM regulators, and secreted factors | 9 | 2.29 × 10−5 | 2.01 × 10−2 |

| Kegg_antigen processing and presentation (89) | Antigen processing and presentation | 4 | 3.36 × 10−5 | 2.01 × 10−2 | |

| Naba_matrisome (1028)† | Ensemble of genes encoding the ECM and ECM-associated proteins | 10 | 4.54 × 10−5 | 2.01 × 10−2 | |

| Naba_secreted factors (344)* | Genes encoding secreted soluble factors | 6 | 7.30 × 10−5 | 3.47 × 10−2 |

The number of genes in each group is shown in parentheses after each cluster or pathway.

The Naba_matrisome and

extracellular matrix (ECM) subset pathways highlight the prevalence of matrix-related differentially expressed gene sets.

Cluster 1 genes are expressed at a baseline level in untreated animals, rise with treatment, and then drop to around baseline when the drug is removed (log2 mean-centered expression values are shown for each cluster in Fig. 10C). Matrix and matrix-associated genes make up the top 5 enriched pathways in this cluster. To understand the role played by matrix genes following this expression pattern, we performed GO mapping for biological processes using g:profiler. The top GO term for Naba_matrisome genes in this cluster was ECM organization, with 25 of 58 genes falling under this term (P = 6.05 × 10−26). Other enriched GO terms for these matrix genes included those involving anatomic structure morphogenesis (P = 4.31 × 10−13), cell adhesion (4.49 × 10−13), collagen fibril organization (P = 5.73 × 10−10), and those impacting vasculature development (P = 8.10 × 10−9; see Supplemental Tables S6–S8 for the full list of GO terms and P values for Naba_matrisome genes in clusters 1–3, respectively). Genes on this list encode elastic fiber proteins such as Fbn-1 and Mfap-5 but also other fiber types, including collagens and fibronectin. Matrix proteases such as Cela1, Adamts-2, and Adamts-12 are also present in this group as well as molecules that impact angiogenesis, including Thbs-1 and Thbs-3.

Cluster 2 and 3 genes most dramatically impact aortic gene expression (positively or negatively) during the off-treatment period. Minoxidil causes variable changes in gene expression in cluster 2 genes (genes in the group may be stable, rise, or fall slightly with 2 wk of minoxidil treatment). However, unlike cluster 1 genes that rise and return to baseline with removal of the drug, those in cluster 2 fall to well below baseline values when the drug is stopped. Eln and its cross-linking enzyme, lysyl oxidase (Lox), are both in cluster 2. Their expression tracings are shown as dashed lines in Fig. 10C. Both rose with treatment (as predicted by our desmosine and histological experiments) and then fell to much lower levels after treatment was discontinued. In addition to Naba_matrisome genes, this cluster also includes immune (the most highly enriched pathway in this cluster), interferon-α/β, MAPK, and activator protein-1 transcription factor-related genes.

Although cluster 2 genes show a reduction in transcription with minoxidil cessation, cluster 3 genes become substantially elevated when minoxidil is stopped. Bone morphogenic protein-responsive genes were noted on GO mapping of Naba_matrisome genes for this cluster (P = 6.84 × 10−4). Oxidative pathway genes are also increasingly expressed after minoxidil discontinuation.

Cluster 4 contains a relatively small gene set that shows decreased expression with minoxidil treatment and rises to baseline levels with its removal (U-shaped pattern). Matrix pathways remain the top hits for enrichment in this cluster of 215 genes, but enrichment analysis revealed no strong associations.

GO analysis of the complete list of 127 minoxidil-regulated Naba_matrisome genes for all four clusters together (Supplemental Tables S9 and S10) was similar to the cluster-specific analysis and highlights the importance of matrix organization genes (P = 5.36 × 10−40) and pathways involving structural morphogenesis (P = 1.01 × 10−26), cell adhesion (P = 1.21 × 10−18), and locomotion (P = 1.55 × 10−12).

DISCUSSION

Genetically mediated ELN insufficiency produces focal stenosis in the aorta and branch pulmonary arteries in the setting of a more generalized arteriopathy that includes high blood pressure and vascular stiffness. Each of these findings is independently associated with negative cardiovascular outcomes, such as stroke, heart attack, and sudden death (10, 43). In addition, pathological increases in vascular stiffness are associated with early-onset cognitive impairment and dementia (11, 17). It is plausible that narrow, stiff arteries such as these provide less flow “reserve” than arteries in healthy individuals. Consequently, we evaluated end-organ effects in our ELN-insufficient mice and found that, in addition to increased blood pressure and reduced arterial compliance, Eln+/− tissues such as the brain were perfused at a lower level, even in the absence of frank stenosis. The data presented here reveal a role for conducting vessel caliber in modulating blood delivery to tissues such as the brain. However, it is also possible that changes in smaller intracranial vessels also contribute to this outcome. Using magnetic resonance angiography, Wint et al. (56) found no differences in patency of the proximal intracranial vessels and their early branches between patients with WBS and control subjects. However, the angiography methods cannot take into account differences in reactivity. Osei-Owusu et al. (36) showed that Eln+/− mice exhibit increased small vessel tone attributable to increased sensitivity to circulating angiotensin II and impaired vasodilation secondary to endothelial dysfunction. Consequently, additional studies are needed to assess the role of resistance vessels in ELN insufficiency-mediated decreased CBF and the impact of minoxidil on those vessels.

A finding of decreased vascular reserve may be especially salient in patients with WBS/SVAS who suffer high rates of cardiac arrest when undergoing anesthetic induction (26), suggesting that acute changes to systemic vascular resistance in the setting of baseline-reduced end-organ flow contribute to negative outcomes. In addition, it is possible that decreased perfusion to the brain during sensitive times during development or as an individual ages may negatively impact neurodevelopmental outcomes. Individuals with WBS have a cognitive profile that includes a reduced IQ, anxiety, and attention concerns (32). Future studies are needed to assess for a correlation between CBF and neurodevelopmental outcomes in WBS/SVAS populations.

To date, no medication has been shown to increase ELN deposition in mature human tissues. As such, most therapies in WBS/SVAS have aimed at treating the clinical signs of the disease. Antihypertensive medications, for example, decrease blood pressure and lower functional arterial stiffness in patients with WBS (21). Work in the Eln+/− mouse model, however, shows that these findings likely reflect a simple shift in blood pressure to the more compliant portion of the arterial pressure-diameter curve rather than vessel remodeling (13). The question remains whether the elevated blood pressure in ELN insufficiency represents a crucial adaptation that stents open the inelastic vessels in an effort to preserve end-organ perfusion (9). Consequently, blood pressure-lowering drugs may have unintended side effects on end-organ perfusion by reducing functional vessel diameter.

Previous work showed that minoxidil, a KATP channel opener, increased ELN expression and deposition in nonjuvenile and aged animals (3, 47, 53), potentially acting through Ca2+-induced differences in ERK1/2 signaling (25). An earlier study by Tsoporis et al. (53) showed a similar result, with minoxidil inducing ELN deposition, an effect they proposed may be due to a decrease in elastase activity. In vitro work by Hayashi et al. (14, 37) in chick smooth muscle cells showed that minoxidil increased ELN expression but also slowed smooth muscle cell proliferation in actively dividing cells, a phenotype that may be driven by minoxidil-driven changes in transcription in MAPK-associated genes in cluster 2. These described effects, combined with the known vasodilator and blood pressure-lowering effects of the drug (6), made it an optimal candidate to induce large vessel remodeling in Eln+/− mice.

Like the previously published studies, our expression, protein, and histological experiments reveal evidence of increased ELN expression and deposition. However, the relative ELN increase is moderated by the simultaneous increase in vessel size. Myograph, ultrasound, and histological experiments all confirmed larger vessels in minoxidil-treated Eln+/− mice, with both a larger OD and lumen area noted. The histological experiments also pointed to a minoxidil-induced thickening of the Eln+/− vessel wall, a finding likely linked to both the uptick in ELN/matrix production and to relaxation of the smooth muscle cells themselves. When the drug was removed, arterial diameter changes persisted for several weeks, suggesting that minoxidil plays a role beyond acute vasodilation.

Distensibility experiments, on the other hand, showed that, although the vessel was larger, the mechanics of the Eln+/− aorta changed little (subtle differences were noted in the Eln+/− carotid), suggesting that the primary effect of the drug is to produce a larger version of the same vessel. Gene expression experiments supported this hypothesis. As discussed, ELN and elastic fiber genes, such as Fbn-1 and Lox, are induced by minoxidil and are downregulated when the drug is removed. At the same time, our experiments indicate that elastic fibers are not the only ECM fiber type impacted by minoxidil administration. In fact, 127 matrix or matrix-associated genes were found to be expressed differentially depending on minoxidil treatment status. The change in expression of multiple ECM fiber types and proteases and the overrepresentation of genes aligning with GO terms like structural morphogenesis, adhesion, and locomotion suggest a large-scale remodeling of the vessel ECM rather than an ELN-specific response. In short, our findings suggest that ELN deposition is increasing because the vessel is enlarging.

The mechanism by which minoxidil induces the changes described above is incompletely understood. Acutely, KATP channel activation produces arterial dilation through smooth muscle relaxation. With longer exposure, Quast et al. (41) reported a role for KATP openers in “clamping the vessel in a relaxed condition,” an effect that would be consistent with the data shown here. Over time, as vessels are chronically inhibited from contraction, the change in wall forces promotes matrix remodeling, as evidenced by the increased transcription of matrix. Of note, similar aortic remodeling changes were not seen with nicardipine (a Ca2+ channel blocker that should also cause vasorelaxation) (13). Although nicardipine is selective for L-type Ca2+ channels in vascular smooth muscle cells over cardiomyocytes, it is known to have more profound vasodilatory effects in certain vascular beds, like the coronaries (24). It is possible, therefore, that the earlier evaluation of the nicardipine-treated aorta and carotid may have missed any vessel remodeling effects the drug may have had on vessels other than those studied. To better understand the mechanism, additional investigation of physiological and transcriptional changes should be undertaken at a wider range of time points and tissue beds using the two medications to determine whether the remodeling effect occurs simply as a response to chronic vasodilation or whether minoxidil may exert a more direct role in gene transcription through the induction of microRNAs or transcription factors.

Although not ELN specific, the combined effect of matrix and vessel remodeling produced by minoxidil therapy generates larger-caliber vessels, and vessel size drives blood flow. In our experiments, carotid blood flow was higher in treated Eln+/− mice and correlated with R4. On ASL, blood flow to the brain in minoxidil-treated Eln+/− mice improved toward untreated WT levels. Together, these findings show the strong potential for minoxidil as a rational therapeutic for the treatment of ELN insufficiency-mediated arteriopathy. In addition, the finding of Hayashi et al. (14) that minoxidil slowed proliferation in actively dividing cells also suggests that, if given at the right developmental time, the drug may inhibit stenosis. Once hyperproliferation has occurred (i.e., after the appearance of stenosis), however, minoxidil may not be able to reduce cell number, as the same study showed no change in cell number when applied to quiescent cells. In general, Eln+/− mice have long-segment, rather than focal, hourglass-type supravalvar aortic stenosis, so we were unable to test this hypothesis.

Of note, minoxidil is already on the market as a third-line blood pressure management agent. It has a side effect profile that includes hirsuitism, coarsening of facial features, cardiomegaly, edema, and pericardial effusion (6, 7, 31). Hirsuitism and facial feature coarseness are difficult to assess in mice, but edema, pericardial effusion, and cardiac hypertrophy, assessed by heart weight-to-body weight ratios, were not noted in our treated Eln+/− mice. Additionally, because vessel diameter differences remained to some degree between treated versus untreated animals even after the drug was removed, continuous treatment with minoxidil may not be needed to maintain the desired therapeutic effect. It is clear that growth is still occurring between 3 and 4 mo of age in mice, as evidenced by increased aortic size in untreated animals in this window. As such, if treatment were continued throughout the entire growing period and then discontinued, it is possible that the remodeling effects would be even more persistent.

In summary, ELN insufficiency-mediated arteriopathy is a systemic disease that produces smaller-caliber vessels with increased arterial stiffness. The loss of ELN has an impact on end-organ perfusion, even in the absence of focal stenosis, a fact that is generally underestimated clinically. Patients with WBS/SVAS have a high rate of chronic morbidities potentially attributable to vascular stiffness and tissue hypoperfusion, such as abdominal pain, attention problems, anxiety, and anesthesia-associated sudden death. Additional work will be needed in clinical studies to confirm changes in end-organ blood flow of affected individuals and correlation with disease features. Although studied here in a rare disease model, the implications of these findings for the treatment of vessels impacted by age-induced vascular stiffness and secondary ELN insufficiency are also important (3). In particular, ELN-mediated vascular disease in aging adults contributes to cardiovascular and neurocognitive morbidity (11). As in patients with genetically mediated ELN insufficiency, treatment of aged individuals with minoxidil may simultaneously improve blood pressure, arterial stiffness, and blood flow, all risk factors for cardiovascular mortality and also for long-term cognitive function. Additional work is needed to evaluate blood flow differences in other key vascular beds, such as the coronaries, lungs, and gut, where ELN-insufficient patients exhibit significant morbidity, potentially attributable to the vasculopathy.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Children’s Discovery Institute Grants CH-FR-2011-169, CH-FR-2011-145, and CH-II-2015-482 (to B. Kozel and M. Shoykhet) at the Washington University School of Medicine/St. Louis Children’s Hospital and was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH Grant HL-006210-01). The efforts of T. Broekelmann were supported by NIH Grants HL-53325 (to R. Mecham) and HL-105314 (to R. Mecham/J. Wagenseil). The efforts of M. Shoykhet were supported by NIH Grant NS-082362.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.H.K., S.C.B., T.J.B., K.M.T., A.K., L.Y., J.D., A. Watson, A. Wardlaw, J.W., and M.S. performed experiments; R.H.K., S.C.B., T.J.B., D.L., K.M.T., A. Watson, A. Wardlaw, J.W., M.S., and B.A.K. analyzed data; R.H.K., S.C.B., T.J.B., K.M.T., L.Y., A. Wardlaw, J.R.G., M.S., and B.A.K. interpreted results of experiments; R.H.K., S.C.B., D.L., M.S., and B.A.K. prepared figures; R.H.K. and S.C.B. drafted manuscript; R.H.K., S.C.B., T.J.B., D.L., K.M.T., A.K., J.D., J.W., J.R.G., M.S., and B.A.K. edited and revised manuscript; R.H.K., S.C.B., T.J.B., D.L., K.M.T., A.K., L.Y., J.D., A. Watson, A. Wardlaw, J.W., J.R.G., M.S., and B.A.K. approved final version of manuscript; S.C.B., J.R.G., M.S., and B.A.K. conceived and designed research.

Supplemental Data

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Dr. Barry Starcher and Dr. Robert P. Mecham for the gift of reagents and/or equipment used in the study. The authors also acknowledge the efforts of the Pathology and Sequencing Cores at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health and the Mouse Cardiovascular Phenotyping Cores at Washington University School of Medicine and NHLBI, in particular, Danielle Springer at NHLBI.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carta L, Wagenseil JE, Knutsen RH, Mariko B, Faury G, Davis EC, Starcher B, Mecham RP, Ramirez F. Discrete contributions of elastic fiber components to arterial development and mechanical compliance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29: 2083–2089, 2009. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.193227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherniske EM, Carpenter TO, Klaiman C, Young E, Bregman J, Insogna K, Schultz RT, Pober BR. Multisystem study of 20 older adults with Williams syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 131: 255–264, 2004. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coquand-Gandit M, Jacob MP, Fhayli W, Romero B, Georgieva M, Bouillot S, Estève E, Andrieu JP, Brasseur S, Bouyon S, Garcia-Honduvilla N, Huber P, Buján J, Atanasova M, Faury G. Chronic treatment with minoxidil induces elastic fiber neosynthesis and functional improvement in the aorta of aged mice. Rejuvenation Res 20: 218–230, 2017. doi: 10.1089/rej.2016.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies M, Udwin O, Howlin P. Adults with Williams syndrome. Preliminary study of social, emotional and behavioural difficulties. Br J Psychiatry 172: 273–276, 1998. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29: 15–21, 2013. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DuCharme DW, Freyburger WA, Graham BE, Carlson RG. Pharmacologic properties of minoxidil: a new hypotensive agent. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 184: 662–670, 1973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earhart RN, Ball J, Nuss DD, Aeling JL. Minoxidil-induced hypertrichosis: treatment with calcium thioglycolate depilatory. South Med J 70: 442–443, 1977. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197704000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faury G, Maher GM, Li DY, Keating MT, Mecham RP, Boyle WA. Relation between outer and luminal diameter in cannulated arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H1745–H1753, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faury G, Pezet M, Knutsen RH, Boyle WA, Heximer SP, McLean SE, Minkes RK, Blumer KJ, Kovacs A, Kelly DP, Li DY, Starcher B, Mecham RP. Developmental adaptation of the mouse cardiovascular system to elastin haploinsufficiency. J Clin Invest 112: 1419–1428, 2003. doi: 10.1172/JCI19028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franklin SS. Beyond blood pressure: Arterial stiffness as a new biomarker of cardiovascular disease. J Am Soc Hypertens 2: 140–151, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, Launer LJ, Laurent S, Lopez OL, Nyenhuis D, Petersen RC, Schneider JA, Tzourio C, Arnett DK, Bennett DA, Chui HC, Higashida RT, Lindquist R, Nilsson PM, Roman GC, Sellke FW, Seshadri S; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia . Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 42: 2672–2713, 2011. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunja-Smith Z. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to quantitate the elastin crosslink desmosine in tissue and urine samples. Anal Biochem 147: 258–264, 1985. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halabi CM, Broekelmann TJ, Knutsen RH, Ye L, Mecham RP, Kozel BA. Chronic antihypertensive treatment improves pulse pressure but not large artery mechanics in a mouse model of congenital vascular stiffness. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H1008–H1016, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00288.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayashi A, Suzuki T, Wachi H, Tajima S, Nishikawa T, Murad S, Pinnell SR. Minoxidil stimulates elastin expression in aortic smooth muscle cells. Arch Biochem Biophys 315: 137–141, 1994. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herscovitch P, Raichle ME. What is the correct value for the brain-blood partition coefficient for water? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 5: 65–69, 1985. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1985.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jahangir A, Terzic A. KATP channel therapeutics at the bedside. J Mol Cell Cardiol 39: 99–112, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kearney-Schwartz A, Rossignol P, Bracard S, Felblinger J, Fay R, Boivin JM, Lecompte T, Lacolley P, Benetos A, Zannad F. Vascular structure and function is correlated to cognitive performance and white matter hyperintensities in older hypertensive patients with subjective memory complaints. Stroke 40: 1229–1236, 2009. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.532853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SG. Quantification of relative cerebral blood flow change by flow-sensitive alternating inversion recovery (FAIR) technique: application to functional mapping. Magn Reson Med 34: 293–301, 1995. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kober F, Duhamel G, Cozzone PJ. Experimental comparison of four FAIR arterial spin labeling techniques for quantification of mouse cerebral blood flow at 4.7 T. NMR Biomed 21: 781–792, 2008. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kober F, Iltis I, Cozzone PJ, Bernard M. Myocardial blood flow mapping in mice using high-resolution spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging: influence of ketamine/xylazine and isoflurane anesthesia. Magn Reson Med 53: 601–606, 2005. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozel BA, Danback JR, Waxler JL, Knutsen RH, de Las Fuentes L, Reusz GS, Kis E, Bhatt AB, Pober BR. Williams syndrome predisposes to vascular stiffness modified by antihypertensive use and copy number changes in NCF1. Hypertension 63: 74–79, 2014. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozel BA, Knutsen RH, Ye L, Ciliberto CH, Broekelmann TJ, Mecham RP. Genetic modifiers of cardiovascular phenotype caused by elastin haploinsufficiency act by extrinsic noncomplementation. J Biol Chem 286: 44926–44936, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.274779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwong KK, Chesler DA, Weisskoff RM, Donahue KM, Davis TL, Ostergaard L, Campbell TA, Rosen BR. MR perfusion studies with T1-weighted echo planar imaging. Magn Reson Med 34: 878–887, 1995. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambert CR, Hill JA, Nichols WW, Feldman RL, Pepine CJ. Coronary and systemic hemodynamic effects of nicardipine. Am J Cardiol 55: 652–656, 1985. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lannoy M, Slove S, Louedec L, Choqueux C, Journé C, Michel JB, Jacob MP. Inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation: a new strategy to stimulate elastogenesis in the aorta. Hypertension 64: 423–430, 2014. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Latham GJ, Ross FJ, Eisses MJ, Richards MJ, Geiduschek JM, Joffe DC. Perioperative morbidity in children with elastin arteriopathy. Paediatr Anaesth 26: 926–935, 2016. doi: 10.1111/pan.12967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li DY, Brooke B, Davis EC, Mecham RP, Sorensen LK, Boak BB, Eichwald E, Keating MT. Elastin is an essential determinant of arterial morphogenesis. Nature 393: 276–280, 1998. doi: 10.1038/30522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li DY, Faury G, Taylor DG, Davis EC, Boyle WA, Mecham RP, Stenzel P, Boak B, Keating MT. Novel arterial pathology in mice and humans hemizygous for elastin. J Clin Invest 102: 1783–1787, 1998. doi: 10.1172/JCI4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30: 923–930, 2014. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15: 550, 2014. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marquez-Julio A, From GL, Uldall PR. Minoxidil in refractory hypertension: benefits, risks. Proc Eur Dial Transplant Assoc 14: 501–508, 1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mervis CB, John AE. Cognitive and behavioral characteristics of children with Williams syndrome: implications for intervention approaches. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 154C: 229–248, 2010. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell GF, van Buchem MA, Sigurdsson S, Gotal JD, Jonsdottir MK, Kjartansson Ó, Garcia M, Aspelund T, Harris TB, Gudnason V, Launer LJ. Arterial stiffness, pressure and flow pulsatility and brain structure and function: the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility–Reykjavik study. Brain 134: 3398–3407, 2011. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris CA, Leonard CO, Dilts C, Demsey SA. Adults with Williams syndrome. Am J Med Genet Suppl 6: 102–107, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naba A, Clauser KR, Ding H, Whittaker CA, Carr SA, Hynes RO. The extracellular matrix: Tools and insights for the “omics” era. Matrix Biol 49: 10–24, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osei-Owusu P, Knutsen RH, Kozel BA, Dietrich HH, Blumer KJ, Mecham RP. Altered reactivity of resistance vasculature contributes to hypertension in elastin insufficiency. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H654–H666, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00601.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pearson G, Robinson F, Beers Gibson T, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr Rev 22: 153–183, 2001. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pell GS, Thomas DL, Lythgoe MF, Calamante F, Howseman AM, Gadian DG, Ordidge RJ. Implementation of quantitative FAIR perfusion imaging with a short repetition time in time-course studies. Magn Reson Med 41: 829–840, 1999. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pober BR, Johnson M, Urban Z. Mechanisms and treatment of cardiovascular disease in Williams-Beuren syndrome. J Clin Invest 118: 1606–1615, 2008. doi: 10.1172/JCI35309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pober BR, Morris CA. Diagnosis and management of medical problems in adults with Williams-Beuren syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 145C: 280–290, 2007. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quast U, Guillon JM, Cavero I. Cellular pharmacology of potassium channel openers in vascular smooth muscle. Cardiovasc Res 28: 805–810, 1994. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reddy GK, Enwemeka CS. A simplified method for the analysis of hydroxyproline in biological tissues. Clin Biochem 29: 225–229, 1996. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(96)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Safar ME. Pulse pressure, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk. Curr Opin Cardiol 15: 258–263, 2000. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]