Abstract

Patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have elevated sympathetic nervous system reactivity and impaired sympathetic and cardiovagal baroreflex sensitivity (BRS). Device-guided slow breathing (DGB) has been shown to lower blood pressure (BP) and sympathetic activity in other patient populations. We hypothesized that DGB acutely lowers BP, heart rate (HR), and improves BRS in PTSD. In 23 prehypertensive veterans with PTSD, we measured continuous BP, ECG, and muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) at rest and during 15 min of DGB at 5 breaths/min (n = 13) or identical sham device breathing at normal rates of 14 breaths/min (sham; n = 10). Sympathetic and cardiovagal BRS was quantified using pharmacological manipulation of BP via the modified Oxford technique at baseline and during the last 5 min of DGB or sham. There was a significant reduction in systolic BP (by −9 ± 2 mmHg, P < 0.001), diastolic BP (by −3 ± 1 mmHg, P = 0.019), mean arterial pressure (by −4 ± 1 mmHg, P = 0.002), and MSNA burst frequency (by −7.8 ± 2.1 bursts/min, P = 0.004) with DGB but no significant change in HR (P > 0.05). Within the sham group, there was no significant change in diastolic BP, mean arterial pressure, HR, or MSNA burst frequency, but there was a small but significant decrease in systolic BP (P = 0.034) and MSNA burst incidence (P = 0.033). Sympathetic BRS increased significantly in the DGB group (−1.08 ± 0.25 to −2.29 ± 0.24 bursts·100 heart beats−1·mmHg−1, P = 0.014) but decreased in the sham group (−1.58 ± 0.34 to –0.82 ± 0.28 bursts·100 heart beats−1·mmHg−1, P = 0.025) (time × device, P = 0.001). There was no significant difference in the change in cardiovagal BRS between the groups (time × device, P = 0.496). DGB acutely lowers BP and MSNA and improves sympathetic but not cardiovagal BRS in prehypertensive veterans with PTSD.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Posttraumatic stress disorder is characterized by augmented sympathetic reactivity, impaired baroreflex sensitivity, and an increased risk for developing hypertension and cardiovascular disease. This is the first study to examine the potential beneficial effects of device-guided slow breathing on hemodynamics, sympathetic activity, and arterial baroreflex sensitivity in prehypertensive veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder.

Keywords: baroreflex, device-guided slow breathing, prehypertension, posttraumatic stress disorder, sympathetic nervous system

INTRODUCTION

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is highly prevalent in both the military and general population. Up to 20% of post-9/11 veterans are estimated to suffer from PTSD (28), and 7% of the general United States population will meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD in their lifetime (5). Multiple large epidemiological studies have demonstrated that PTSD is independently associated with a significantly greater risk for developing hypertension, other cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease, and mortality (8, 32). Although the mechanisms leading to increased cardiovascular disease risk are not fully understood, recent evidence suggests chronically heightened sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity and reactivity (24, 44) in patients with PTSD that is mediated by altered arterial baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) (44). SNS overactivity has a major role in causing and sustaining hypertension (21) and contributes to the development of heart failure (31), arrhythmias (22), and atherogenesis (17). Moreover, exaggerated SNS responses during mental stress are associated with an increased risk of hypertension (40) and cardiovascular disease (46). Peripheral sympatholytics such as β-blockers and α-blockers are often prescribed for PTSD symptoms; however, treatment is often complicated by adverse side effects including hypotension, orthostasis, fatigue, and erectile dysfunction. In addition, these agents cause a reflex increase in central SNS activity (9, 23), and long-term β-blocker use is associated with development of hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance (9) and so is a particularly less desirable treatment option in young veterans already at higher cardiovascular disease risk. Therefore, safe and effective alternative treatments targeting increased SNS activation are needed in this high-risk population.

Therapeutic interventions targeting SNS overactivity and blunted arterial BRS have the potential to mitigate future risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease in PTSD. Device-guided slow breathing (DGB), in which breathing is slowed to 5–6 breaths/min via an interactive biofeedback device, is a currently Federal Drug Administration-approved for relaxation and the adjunctive treatment of hypertension. Although the evidence is conflicting (1, 11, 34, 35), DGB has been shown in some studies to lower blood pressure (BP) and sympathetic nerve activity in humans with hypertension (25–27, 30, 43). However, the effect of DGB on BRS is unknown, and the potential benefits of DGB in patients with PTSD have never previously been explored and could represent a novel nonpharmacological approach to improving autonomic balance in this patient population. We hypothesized that DGB acutely lowers BP and muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) and increases sympathetic and cardiovagal BRS in prehypertensive veterans with PTSD.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty-three post-9/11 veterans with prehypertension (resting BP between 120 and 139/80–89 mmHg) and combat-related PTSD were enrolled over a period of 2 yr. All participants had a diagnosis of PTSD in their medical record. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, hypertension, diabetes, current smokers, heart disease, illicit drug use, excessive alcohol use (>2 drinks/day), hyperlipidemia, autonomic dysfunction, medications known to affect SNS activity (clonidine, β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers), treatment with monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and any serious systemic disease. This study was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board and the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center Research and Development Committee. All participants signed an approved informed consent document before study procedures.

Measurements

Blood pressure.

Seated BP was measured three times, separated by 5 min, using an automated sphygmomanometer (Omron HEM-907XL, Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan). During the experimental protocol, beat-to-beat arterial BP was measured continuously and noninvasively using digital pulse photoplethysmography (CNAP, CNSystems, Graz, Austria) (19). Absolute values of BP were calibrated with upper arm BP readings at the start and every 15 min throughout the study.

Muscle sympathetic nerve activity.

Multiunit postganglionic sympathetic nerve activity directed to muscle (MSNA) was recorded from the peroneal nerve using microneurography, as previously described (58, 61). A tungsten microelectrode (tip diameter: 5–15 μm, Bioengineering, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) was inserted into the nerve, and a reference microelectrode was inserted in close proximity. Signals were amplified (total gain: 50,000–100,000), filtered (700–2000 Hz), rectified, and integrated (time constant: 0.1 s) to obtain a mean voltage display of sympathetic nerve activity (Nerve Traffic Analyzer, model 662C-4, Bioengineering, University of Iowa). The neurogram was recorded using LabChart 7 (PowerLab 16sp, AD Instruments, Sydney, NSW, Australia) along with continuous ECG recordings using a bioamp. All MSNA recordings met previously established criteria (12, 13, 39) and were analyzed by a single investigator who was blinded to the device used by the participant. MSNA was expressed as burst frequency (bursts/min) and burst incidence (bursts/100 heart beats).

Arterial BRS testing using the modified Oxford technique.

The gold standard method for evaluation of arterial BRS is performed by measuring changes in MSNA and R-R interval during arterial BP changes induced by nitroprusside and phenylephrine (50). Sodium nitroprusside (100 μg in 10 ml of normal saline) was bolused through an antecubital intravenous catheter followed 60 s later by an intravenous bolus of phenylephrine (150 μg in 10 ml of normal saline) during continuous MSNA, ECG, and hemodynamic monitoring. Medications were room temperature at the time of administration. These medications induce a decrease of ∼15 mmHg followed by an increase of ∼15 mmHg in arterial BP. Sympathetic BRS was defined as the slope of the linear regression between MSNA burst incidence and diastolic BP (DBP) binned in 3-mmHg pressure ranges (14). A steeper slope represents a greater increase in MSNA in response to low BP and a greater suppression of MSNA in response to high BP, i.e., increased sympathetic BRS, whereas a flatter slope represents decreased sympathetic BRS. Cardiovagal BRS was assessed as the slope of the linear regression between ECG R-R intervals and systolic BP (SBP; binned over 2-mmHg pressure ranges) (45). Similarly, a steeper slope represents increased cardiovagal BRS, whereas a flatter slope indicates blunted cardiovagal BRS. At least 5 min of total data were analyzed for each BRS assessment.

Device-guided breathing.

DGB was performed using the RESPeRATE (InterCure) device (DGB group) or an identical sham device (sham group) for 15 min during the testing procedure in the laboratory. The device is composed of an elastic belt with a respiration sensor placed around the upper abdomen for biofeedback and earbuds used for auditory guidance (56). The device monitors respiratory rate, calculates inspiration and expiration times, and generates a personalized melody of two distinct ascending and descending tones for inhalation and exhalation. Participants effortlessly entrain their breathing pattern with the tones, and the device gradually guides the user to a prolonged expiration time and slower respiratory rate of around 5 breaths/min. The device automatically stores usage data, allowing for quantification of adherence and performance. The sham device was identical to the DGB device, using the same display, musical tones, and respiratory sensor belt. However, the sham device guided respiratory rates at a normal physiological rate of 14 breaths/min.

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale.

The diagnosis of PTSD was confirmed in all participants using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) IV (CAPS-IV). CAPS-IV was administered and interpreted by a single trained investigator for all participants. A severity score of ≥45 was required to confirm the presence of PTSD (62).

Experimental Protocol

All participants presented for one or two screening visits before experimental procedures. During the screening visit(s), seated BPs were taken a total of three times, separated by 5 min, and averaged to ensure the absence of hypertension and obtain baseline values. CAPS-IV was performed during the screening visit to confirm the diagnosis of PTSD. Participants were trained on the use of the breathing device during the screening visit. Female participants underwent a urine pregnancy test to rule out pregnancy. Participants were randomized to the DGB device (n = 13) during which respiratory rate was slowed to subphysiological levels of ~5 breaths/min or an identical sham device (n = 10) during which respiratory rate was guided to 14 breaths/min using the same biofeedback mechanism.

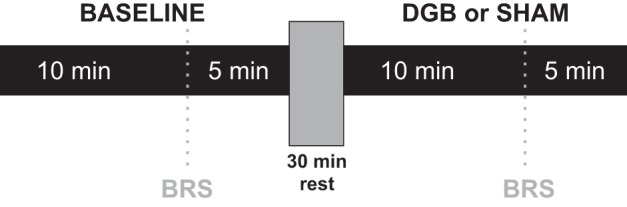

On the day of the study, participants reported to the laboratory in the morning after abstaining from food, medications, caffeine, and alcohol for at least 12 h and exercise for at least 24 h. The study room was quiet, semidark, and at a temperate of ∼21°C. Participants were placed in a supine position on a comfortable stretcher. A 20-gauge intravenous catheter was placed into the antecubital vein of the arm for the administration of medications during BRS assessments. Finger cuffs were fitted and placed on the fingers of the dominant arm for continuous beat-to-beat arterial BP measurements, and an upper arm cuff was placed for intermittent automatic calibrations with the finger cuffs. ECG patch electrodes were placed for continuous ECG recordings, and two belts with respiratory rate sensors were placed around the upper abdomen for monitoring of continuous respiratory rates and for biofeedback as part of the breathing intervention. The leg was positioned for microneurography, and the tungsten microelectrode was inserted and manipulated to obtain a satisfactory nerve recording. After 10 min of rest, baseline BP, heart rate (HR), and MSNA were recorded continuously for 15 min. After baseline measurements, BRS testing was performed by infusing intravenous boluses of 100 μg nitroprusside followed 60 s later by 150 μg phenylephrine, as described above. After 30 min of rest to ensure sufficient washout of drugs and return to baseline conditions, participants underwent 15 min of breathing intervention with either the DGB or sham device. Intravenous nitroprusside and phenylephrine were infused again for BRS testing during the last 5 min of DGB or sham procedures (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Summary of the experimental protocol. Baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) was assessed during the last 5 min of baseline and device-guided slow breathing (DGB) or sham breathing (sham).

Data Analysis

MSNA and BRS assessment.

MSNA and ECG data were exported from Labchart to WinCPRS (Absolute Aliens, Turku, Finland) for analysis. R waves were detected and marked from the continuous ECG recording. MSNA bursts were automatically detected by the program using the following criteria: 3:1 burst-to-noise ratio within a 0.5-s search window, with an average latency in burst occurrence of 1.2–1.4 s from the previous R wave. After automatic detection, the ECG and MSNA neurograms were visually inspected for accuracy of detection by a single investigator (J. Park) without knowledge of the experimental status as DGB or sham. MSNA was expressed as burst frequency (bursts/min) and burst incidence (bursts/100 heart beats).

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed statistically using commercial software (SPSS 22.0, IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY) and the R Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (47). An independent t-test was used to compare baseline characteristics, and significantly different variables were accounted for in the analysis. The response to the breathing intervention (DGB vs. sham) was calculated as a mean reactivity for each 2-min block of the test period (mean value for each consecutive 2 min of the intervention minus the corresponding mean baseline value). A linear mixed model (LMM) analysis (see model description below) was used with participants as random factor and the variables device and time as fixed factors to assess within-group and between-group differences over time during the breathing intervention. Repeated-measures ANOVA with device (DGB vs. sham) as a between factor and time (baseline and intervention) as a within factor was used to analyze the change in sympathetic and cardiovagal BRS during the breathing intervention. All P values are two-tailed, with the significance level set at α < 0.05.

LMM analysis.

Estimation and inference of LMM was performed with the lme4 (4) and lmerTest (33) packages in the R statistical programming environment (47). LMM was used to compare differences in “slopes” of DGB and sham groups, which indicate rates of change during intervention. The formula of the LMM can be specified as follows:

| (1) |

When between-group differences were tested, the formula of the LMM can be specified as follows:

| (2) |

In both formulas, ti is the time of the ith observation during the intervention (time = breathing time elapsed) and Yij is the measurement at the ith level of time on the jth subject. The binary variable device represents the study group: device = 1 for any subject in the sham group and device = 2 in the DGB group. In addition, we added two sets of subject-specific zero-mean Gaussian random variables, and to serve as random intercepts and and to serve as random slopes, respectively. These terms effectively control for individual variability during intervention. The last terms of the formulas, and , represent random error and also follow a zero-mean Gaussian distribution. We assumed that all random effects and random errors were jointly independent. In Eq. 1, coefficient a1 can be interpreted as the rate of change over time in one study group. If a1 is significantly positive (or negative), we can conclude there is a significant increasing (or decreasing) trend in the mean value of Y over time. In Eq. 2, coefficient b3 can be interpreted as the difference in rates of change over time between groups. Statistical significance in the LMM analysis was evaluated by t-test statistics with a Satterthwaite approximation to degrees of freedom.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Twenty-three post-9/11 veterans with prehypertension and PTSD were enrolled and randomized to the DGB (n = 13) and sham (n = 10) groups. Age, body mass index, race, sex, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use were not significantly different between groups (Table 1). The majority of participants in both groups were African-American men. The diagnosis of PTSD was confirmed in all participants using CAPS-IV. Both groups had comparable CAPS-IV scores. Resting SBP, DBP, mean arterial pressure (MAP), and HR were not significantly different between DGB and sham groups (P > 0.05). MSNA was significantly higher at baseline in the DGB group when expressed as burst frequency (27 ± 3 vs. 14 ± 1 busts/min, P = 0.004) and burst incidence (40 ± 4 vs. 22 ± 2 busts/min, P = 0.001). Resting cardiovagal BRS (13.1 ± 1.6 vs. 11.9 ± 2.4, P = 0.659) and sympathetic BRS (−1.1 ± 0.2 vs. −1.5 ± 0.3, P = 0.379) were not different between groups at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | Device-Guided Slow Breathing Group | Sham Group | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 13 | 10 | |

| Age, yr | 35 ± 2 | 32 ± 1 | 0.182 |

| Sex, men/women | 12/1 | 9/1 | 0.846 |

| Race, non-Hispanic black/non-Hispanic white | 9/4 | 9/1 | 0.231 |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use, n (%) | 3 (23) | 3 (30) | 0.537 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 32 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 0.354 |

| Clinician-administered posttraumatic stress disorder scale score | 72 ± 5 | 68 ± 6 | 0.594 |

| Sysolic blood pressure, mmHg | 120 ± 3 | 124 ± 4 | 0.431 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 78 ± 2 | 80 ± 3 | 0.676 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 92 ± 3 | 95 ± 3 | 0.555 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 72 ± 4 | 74 ± 4 | 0.795 |

| Respiratory rate breaths/min | 19 ± 1 | 18 ± 1 | 0.346 |

| MSNA, bursts | 27 ± 3 | 14 ± 1 | 0.004* |

| MSNA, bursts/100 heart beats | 40 ± 4 | 22 ± 2 | 0.001* |

| Sympathetic BRS, bursts·100 heart beats−1·mmHg−1 | −1.1 ± 0.2 | −1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.379 |

| Cardiovagal BRS, ms/mmHg | 13.1 ± 1.6 | 11.9 ± 2.4 | 0.659 |

Data are means ± SE; n, number of subjects/group [for muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) and sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity (BRS), n = 12 in the device-guided slow breathing group and 10 in the sham group]. Seated blood pressure values were measured.

Two-tailed P < 0.05.

Hemodynamic Responses During the Breathing Intervention

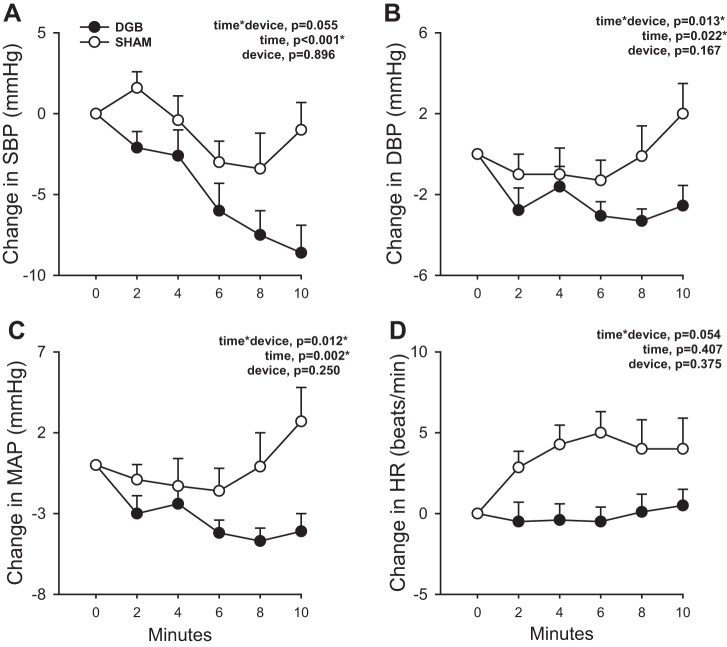

Figure 2 shows the change in arterial BP and HR during the breathing intervention. Goal respiratory rates of 5 breaths/min in the DGB group and 14 breaths/min in the sham group were achieved (data not shown). During the 10 min of breathing intervention, there was a trend toward a difference in the SBP response (time × group, P = 0.055; Fig. 2A) and a significant difference in the change in DBP (time × group, P = 0.013; Fig. 2B) and MAP (time × group, P = 0.012) responses between DGB and sham groups. There was also a trend toward a significant difference in the HR response between groups (time × group, P = 0.054; Fig. 2D). These differences remained significant after adjustment for sex and race. Within the DGB group, SBP (P < 0.001), DBP (P = 0.019), and MAP (P = 0.002) significantly decreased in response to slow breathing. HR, however, remained unchanged (P = 0.285). Within the sham group, there was also a significant decrease in SBP (P = 0.034) during the breathing intervention, although the degree of reduction was less than with the DGB intervention. DBP (P = 0.177) and MAP (P = 0.416) did not significantly change, whereas HR (P = 0.057) tended to increase with sham intervention.

Fig. 2.

A−D: change in systolic blood pressure (SBP; A), diastolic blood pressure (DBP; B), mean arterial pressure (MAP; C) and heart rate (HR; D) during 10 min of breathing intervention using a device-guided slow breathing (DGB) device or sham device (sham). There was a significantly greater decrease in SBP, DBP, and MAP over time with the DGB compared with sham intervention. HR tended to increase over time with the sham intervention compared with the DGB intervention. Data are reported as means ± SE; n = 13 for the DGB group and 10 for the sham group. *P < 0.05.

Sympathoneural Responses During the Breathing Intervention

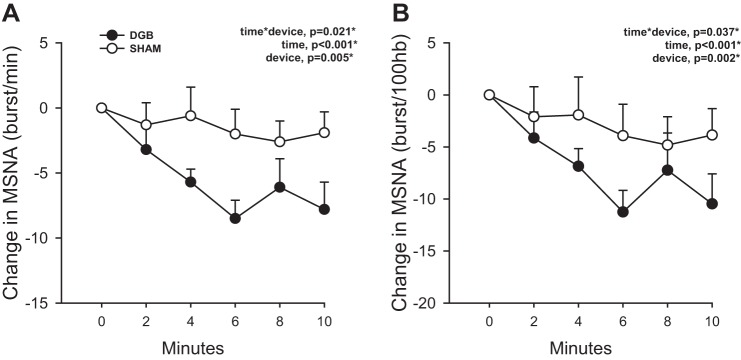

Figure 3 shows the changes in MSNA burst frequency and burst incidence during the 10-min breathing intervention. The change in MSNA burst frequency (in bursts/min, time × group, P = 0.021) and burst incidence (time × group, P = 0.037) was significantly different between groups. Similar to BP responses, MSNA significantly decreased over time in response to the breathing intervention (time, P < 0.001), and this overall decrease was solely driven by a significantly greater reduction in MSNA in the DGB group (P < 0.05). Again, these differences remained significant after adjustment for sex and race. Within the DGB group, MSNA burst frequency (P = 0.004) and MSNA burst incidence (P = 0.003) significantly decreased during the intervention. Within the sham group, MSNA burst incidence (P = 0.033) also significantly decreased and MSNA burst frequency tended to decrease (P = 0.060), although the magnitude of reduction was less than that in the DGB group. The group randomly assigned to DGB had higher resting MSNA compared with the sham group. This difference, however, was accounted for in the statistical model (see LMM analysis); given the baseline MSNA difference and its possible confounding effect on the neural response to the breathing intervention, baseline MSNA was included as a covariate in the LMM analysis and adjusted for in the time × device P value shown in Fig. 3. The interaction effect remained significant despite adjusting for the baseline MSNA difference.

Fig. 3.

A and B: change in muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) quantified as burst frequency (A) and burst incidence (B) during 10 min of breathing intervention using a device-guided slow breathing (DGB) device versus sham device (sham). There was a significantly greater decrease in MSNA burst frequency (bursts/min) and burst incidence [bursts/100 heart beats (hb)] during during the DGB intervention compared with the sham intervention. n = 10 for the DGB group and 10 for the sham group. *P < 0.05.

BRS During the Breathing Intervention

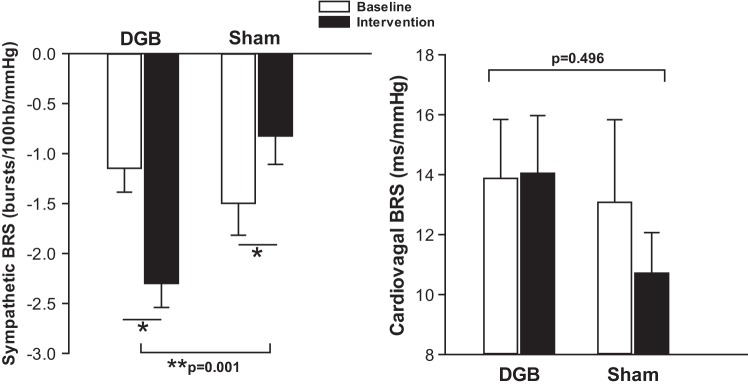

Figure 4 shows sympathetic and cardiovagal BRS at baseline and during the breathing intervention in DGB versus sham groups. There was a significant increase (i.e., more negative slope) in sympathetic BRS from baseline during the DGB intervention (−1.08 ± 0.25 to −2.29 ± 0.24 bursts·100 heart beats−1·mmHg−1, P = 0.014), whereas there was a significant decrease in sympathetic BRS (i.e., less negative slope) during the sham intervention (−1.58 ± 0.34 to –0.82 ± 0.28 bursts·100 heart beats−1·mmHg−1, P = 0.025) (time × device, P = 0.001). The change in cardiovagal BRS was not significantly different between groups (13.87 ± 1.96 to 14.04 ± 1.92 ms/mmHg for the DGB group vs. 13.07 ± 2.75 to 10.71 ± 1.35 ms/mmHg for the sham group, P = 0.496).

Fig. 4.

Change in sympathetic and cardiovagal baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) during device-guided slow breathing (DGB) and sham device (sham) interventions. Sympathetic BRS was significantly altered from baseline with the DGB intervention compared with the sham intervention. Sympathetic BRS significantly increased with the DGB intervention and decreased with the sham intervention. There was no significant change from baseline in cardiovagal BRS during both DGB and sham interventions. n = 10 for the DGB group and 9 for the sham group. *P < 0.05 for within-group comparison. P < 0.05 for between-group comparison.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the effects of DGB against an identical sham device on BP and MSNA in a population of patients with PTSD. It is also the first study to examine the effects of DGB on arterial BRS. The major new findings of this study are as follows: 1) the DGB intervention acutely lowered BP to a greater degree than the sham intervention; 2) although both DGB and sham interventions acutely lowered MSNA in PTSD, the magnitude in the reduction of MSNA was significantly greater with the DGB intervention; 3) sympathetic BRS was significantly improved during the DGB intervention but was significantly worsened during the sham intervention; and 4) there was no change in cardiovagal BRS during DGB or sham interventions. Together, these changes suggest that DGB may have beneficial neurohemodynamic effects in patients with PTSD.

In the present study, we investigated the potential beneficial effects of DGB, a nonpharmacological and noninvasive intervention, on hemodynamics and autonomic function in PTSD. DGB, during which breathing is slowed to a measurable target of 5–6 breaths/min via an interactive biofeedback device, has been shown in some, but not all (11, 27, 34–36), studies to acutely lower BP and sympathetic nerve activity in humans with hypertension (2, 26, 27, 30, 43) as well as lead to baseline improvements after 8 wk of daily use (16, 52, 53). We observed that 10 min of DGB significantly lowered SBP (−9 mmHg) and DBP (−3 mmHg) in young prehypertensive patients with PTSD. Some prior studies have demonstrated a similar acute reduction in SBP of ~6–8 mmHg in patients with hypertension (30, 43) and chronic heart failure (7) as well as a sustained effect after 8 wk of use in patients with hypertension (25) and diabetes (29). In contrast, others (1, 34, 35, 59) have reported no change in BP with DGB after 8−9 wk of daily at-home slow breathing. One distinguishing feature of the present study is the study population composed of young, prehypertensive veterans under chronic stress due to symptomatic PTSD. The positive effect of DGB on hemodynamics may be augmented in this population due to a “relaxation” component of the DGB intervention in this patient population with high SNS activity and blunted BRS at baseline (38).

An additional strength of the present study is the use of an identical sham device that uses the same biofeedback and auditory tones for comparison, which allows for masking and a better control intervention compared with calm music or spontaneous breathing, as used in prior studies. Of note, BP and MSNA also decreased in the sham group, although to a lesser extent than in the DGB group, whereas HR tended to increase in sham group. The mechanisms underlying the hemodynamic effect of sham breathing are unclear but may be due to a relaxation component even with the sham device as well as physiological effects of paced breathing compared with spontaneous breathing. Although the respiratory rate was guided at a normal respiratory rate of 14 breaths/min during the sham intervention, participants may have breathed more deeply at the same rate, leading to higher tidal volumes and minute ventilation that may have had differential physiological effects. Prior studies have shown that hyperventilation may lead to an increased SNS influence on the heart (51), which could potentially explain the observed increase in HR and decrease in sympathetic BRS during sham breathing in the present study. Hyperventilation has also been reported to influence arterial baroreflex control of the heart (6, 7, 30).

Breathing exercises are often used as an adjunctive behavioral therapy in PTSD and anxiety disorders. Several studies have suggested that breathing-based meditation decreases PTSD symptoms in United States military veterans (55, 60). In a small study, breathing biofeedback in addition to cognitive behavioral therapy resulted in faster clinical improvement in PTSD symptoms (49). In panic disorder, studies have suggested that a biofeedback-assisted respiratory rate reduction with increased end-tidal Pco2 leads to a reduction in panic symptoms (41, 42). Given the increasing use of breathing interventions for stress management in a variety of conditions, identifying the ideal modality, rates, and minute ventilation on autonomic indexes is clinically relevant.

In our sample, MSNA at rest was higher in the DGB group compared with the sham group. This baseline difference occurred despite a random assignment to DGB versus sham intervention. Although MSNA is known to be consistent within individuals (18), it is highly variable between individuals (57). This between-subject variability could therefore explain the significant difference observed between the DGB and sham groups at baseline. The mechanisms underlying the acute BP-lowering effect of slow breathing remains unclear, but our observation that DGB significantly lowers MSNA in PTSD even after controlling for baseline MSNA, sex, and race suggests that DGB may modulate neural sympathetic output. These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting that DGB compared with calm music (43) or spontaneous breathing (26, 27) significantly reduced MSNA in patients with hypertension and chronic heart failure. Breathing at subphysiological rates has been shown to acutely lower MSNA (43), increase low-frequency HR variability (2), and improve BRS (6, 7, 30) in healthy humans as well as in patients with hypertension and heart failure. One potential mechanism by which DGB lowers MSNA might be via a reduction in end-tidal CO2. Anderson et al. (2) reported that a group of otherwise healthy patients with hypertension had a progressive and significant reduction in end-tidal CO2 as well as an increase in tidal volume in response to a 15-min DGB session compared with spontaneously breathing control subjects. Goso et al. (20) also advanced the hypothesis that a greater tidal volume via higher lung inflation might be required to activate lung stretch receptors and suppress MSNA activation. Thus, DGB may reduce the SNS overactivity present in patients with PTSD via the modulation of chemoreceptors by end-tidal CO2 (2) or via activation of pulmonary mechanoreceptors in response to increased tidal volume (54). Interestingly, although MSNA correlates more strongly with DBP changes, we observed a relatively greater reduction in SBP with DGB. Other mechanisms besides a reduction in sympathetic activity such as reductions in other vasoconstrictors like angiotensin II, increases in vasodilators such as nitric oxide, or parasympathetic withdrawal may also modulate the BP response to DGB.

We (44) have previously reported that patients with PTSD have blunted sympathetic and cardiovagal BRS that could contribute to SNS overactivation and increased BP by impairing the ability to modulate autonomic function in response to changes in arterial BP (63). The present study revealed that the DGB intervention significantly increased sympathetic BRS compared with the sham intervention, suggesting that DGB may decrease MSNA in PTSD by increasing the sensitization of the sympathetic arm of the arterial baroreflex. These findings may also suggest that during DGB, a reduction in sympathetic activity by the chemoreceptor is not opposed by the arterial baroreflex. In healthy humans, slow breathing has been reported to induce a shift toward parasympathetic predominance (10, 64) and augment vagal power (64). Previous studies have also reported an increase in cardiovagal BRS measured via spectral analysis (37) in response to slow breathing in patients with hypertension (30) and chronic heart failure (7). In the present study, cardiovagal BRS did not increase with DGB, although there was a trend towards improvement in this group, consistent with the shift toward parasympathetic predominance previously described with slow breathing to 6 breaths/min (15, 48). In summary, DGB acutely lowered BP and MSNA and improved sympathetic BRS in PTSD. Further studies to assess potential long-term benefits of DGB on autonomic function, hemodynamics, and clinical outcomes in PTSD are warranted.

Limitations

We recognize several limitations to our study. First, the study population was mainly composed of men and African-American veterans with PTSD; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to women, other racial groups, or the nonveteran population. Furthermore, oral contraceptives and the phase of the menstrual cycle may influence MSNA and BP responses, and these variables were not tracked in our two female participants. Second, the sham device guided breathing to a rate of 14 breaths/min. This rate was slightly lower than the participant’s spontaneous normal breathing rate (which ranged between 16 and 19 breaths/min), and the auditory guidance may have modified resting tidal volumes that may have led to modulations in autonomic control within the sham group. Third, we did not measure tidal volume or end-tidal CO2 in this study, which could have added insights into the possible mechanisms involved in the acute MSNA reduction during DGB. Fourth, only SNS activity directed to the muscle (MSNA) was measured during each intervention. The effects of DGB on sympathetic innervation to other organs such as the heart and kidneys as well as parasympathetic activity remain unknown. Finally, the long-term effects of slow breathing on autonomic function have shown mixed results (11, 27). We investigated the acute changes in hemodynamics and neurocirculatory control during a single 10-min session of DGB and the mechanisms underlying the sympathoinhibitory effect of DGB remain unexplored. Whether long-term DGB intervention leads to sustained improvements in hemodynamics and SNS activity in patients with PTSD should be evaluated in future studies.

GRANTS

This work was supported by United States Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences Research and Development Program Merit Review Award I01CX001065 (to J. Park); American Heart Association National Affiliate Collaborative Sciences Award 15CSA24340001; resources and the use of facilities at the Clinical Studies Center of the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center; the Atlanta Research and Education Foundation; National Institutes of Health (NIH) Training Grant T32-DK-00756; Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development and the Clinical Studies Center (Decatur, GA); the Atlanta Research and Education Foundation; a University Research Council grant from Emory University; and the Atlanta Clinical and Translational Science Institute supported by NIH Grant UL1-RR-025008.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

I.F., S.D.N., M.L.K., D.D., and J.P. performed experiments; I.F. and Y.L. analyzed data; I.F. and J.P. interpreted results of experiments; I.F. prepared figures; I.F. drafted manuscript; I.F., P.J.M., S.D.N., Y.L., B.O.R., and J.P. edited and revised manuscript; I.F., P.J.M., S.D.N., M.L.K., Y.L., D.D., B.O.R., and J.P. approved final version of manuscript; J.P. conceived and designed research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank JooHee Kang for assistance with some aspects of this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altena MR, Kleefstra N, Logtenberg SJ, Groenier KH, Houweling ST, Bilo HJ. Effect of device-guided breathing exercises on blood pressure in patients with hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Blood Press 18: 273–279, 2009. doi: 10.3109/08037050903272925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson DE, McNeely JD, Windham BG. Device-guided slow-breathing effects on end-tidal CO(2) and heart-rate variability. Psychol Health Med 14: 667–679, 2009. doi: 10.1080/13548500903322791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bates DM, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67: 1–48, 2015. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bedi US, Arora R. Cardiovascular manifestations of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Natl Med Assoc 99: 642–649, 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernardi L, Gabutti A, Porta C, Spicuzza L. Slow breathing reduces chemoreflex response to hypoxia and hypercapnia, and increases baroreflex sensitivity. J Hypertens 19: 2221–2229, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200112000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernardi L, Porta C, Spicuzza L, Bellwon J, Spadacini G, Frey AW, Yeung LY, Sanderson JE, Pedretti R, Tramarin R. Slow breathing increases arterial baroreflex sensitivity in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 105: 143–145, 2002. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.103311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brudey C, Park J, Wiaderkiewicz J, Kobayashi I, Mellman TA, Marvar PJ. Autonomic and inflammatory consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and the link to cardiovascular disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309: R315–R321, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00343.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carella AM, Antonucci G, Conte M, Di Pumpo M, Giancola A, Antonucci E. Antihypertensive treatment with beta-blockers in the metabolic syndrome: a review. Curr Diabetes Rev 6: 215–221, 2010. doi: 10.2174/157339910791658844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang Q, Liu R, Shen Z. Effects of slow breathing rate on blood pressure and heart rate variabilities. Int J Cardiol 169: e6–e8, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Barros S, da Silva GV, de Gusmão JL, de Araújo TG, de Souza DR, Cardoso CG Jr, Oneda B, Mion D Jr. Effects of long term device-guided slow breathing on sympathetic nervous activity in hypertensive patients: a randomized open-label clinical trial. Blood Press 26: 359–365, 2017. doi: 10.1080/08037051.2017.1357109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delius W, Hagbarth KE, Hongell A, Wallin BG. General characteristics of sympathetic activity in human muscle nerves. Acta Physiol Scand 84: 65–81, 1972. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delius W, Hagbarth KE, Hongell A, Wallin BG. Manoeuvres affecting sympathetic outflow in human muscle nerves. Acta Physiol Scand 84: 82–94, 1972. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dutoit AP, Hart EC, Charkoudian N, Wallin BG, Curry TB, Joyner MJ. Cardiac baroreflex sensitivity is not correlated to sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity within healthy, young humans. Hypertension 56: 1118–1123, 2010. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.158329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckberg DL, Kifle YT, Roberts VL. Phase relationship between normal human respiration and baroreflex responsiveness. J Physiol 304: 489–502, 1980. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott WJ, Childers WK. Should β blockers no longer be considered first-line therapy for the treatment of essential hypertension without comorbidities? Curr Cardiol Rep 13: 507–516, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s11886-011-0216-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erami C, Zhang H, Ho JG, French DM, Faber JE. α1-Adrenoceptor stimulation directly induces growth of vascular wall in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H1577–H1587, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00218.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fonkoue IT, Carter JR. Sympathetic neural reactivity to mental stress in humans: test-retest reproducibility. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309: R1380–R1386, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00344.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortin J, Marte W, Grüllenberger R, Hacker A, Habenbacher W, Heller A, Wagner C, Wach P, Skrabal F. Continuous non-invasive blood pressure monitoring using concentrically interlocking control loops. Comput Biol Med 36: 941–957, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goso Y, Asanoi H, Ishise H, Kameyama T, Hirai T, Nozawa T, Takashima S, Umeno K, Inoue H. Respiratory modulation of muscle sympathetic nerve activity in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation 104: 418–423, 2001. doi: 10.1161/hc2901.093111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grassi G. Assessment of sympathetic cardiovascular drive in human hypertension: achievements and perspectives. Hypertension 54: 690–697, 2009. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.119883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grassi G, Seravalle G, Dell’Oro R, Facchini A, Ilardo V, Mancia G. Sympathetic and baroreflex function in hypertensive or heart failure patients with ventricular arrhythmias. J Hypertens 22: 1747–1753, 2004. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200409000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grassi G, Seravalle G, Stella ML, Turri C, Zanchetti A, Mancia G. Sympathoexcitatory responses to the acute blood pressure fall induced by central or peripheral antihypertensive drugs. Am J Hypertens 13: 29–34, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(99)00150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grenon SM, Owens CD, Alley H, Perez S, Whooley MA, Neylan TC, Aschbacher K, Gasper WJ, Hilton JF, Cohen BE. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Is Associated With Worse Endothelial Function Among Veterans. J Am Heart Assoc 5: e003010, 2016. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.003010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grossman E, Grossman A, Schein MH, Zimlichman R, Gavish B. Breathing-control lowers blood pressure. J Hum Hypertens 15: 263–269, 2001. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harada D, Asanoi H, Takagawa J, Ishise H, Ueno H, Oda Y, Goso Y, Joho S, Inoue H. Slow and deep respiration suppresses steady-state sympathetic nerve activity in patients with chronic heart failure: from modeling to clinical application. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1159–H1168, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00109.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hering D, Kucharska W, Kara T, Somers VK, Parati G, Narkiewicz K. Effects of acute and long-term slow breathing exercise on muscle sympathetic nerve activity in untreated male patients with hypertension. J Hypertens 31: 739–746, 2013. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835eb2cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med 351: 13–22, 2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howorka K, Pumprla J, Tamm J, Schabmann A, Klomfar S, Kostineak E, Howorka N, Sovova E. Effects of guided breathing on blood pressure and heart rate variability in hypertensive diabetic patients. Auton Neurosci 179: 131–137, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2013.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joseph CN, Porta C, Casucci G, Casiraghi N, Maffeis M, Rossi M, Bernardi L. Slow breathing improves arterial baroreflex sensitivity and decreases blood pressure in essential hypertension. Hypertension 46: 714–718, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000179581.68566.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Julius S. Corcoran lecture. Sympathetic hyperactivity and coronary risk in hypertension. Hypertension 21: 886–893, 1993. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.21.6.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kibler JL, Joshi K, Ma M. Hypertension in relation to posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Behav Med 34: 125–132, 2009. doi: 10.3200/BMED.34.4.125-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuznetsova AB, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. ImerTest: tests in linear mixed effects models. R package version 2.0–33. 2016. https://www.jstatsoft.org/article/view/v082i13. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landman GW, Drion I, van Hateren KJ, van Dijk PR, Logtenberg SJ, Lambert J, Groenier KH, Bilo HJ, Kleefstra N. Device-guided breathing as treatment for hypertension in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1346–1350, 2013. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Logtenberg SJ, Kleefstra N, Houweling ST, Groenier KH, Bilo HJ. Effect of device-guided breathing exercises on blood pressure in hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. J Hypertens 25: 241–246, 2007. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32801040d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahtani KR, Nunan D, Heneghan CJ. Device-guided breathing exercises in the control of human blood pressure: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens 30: 852–860, 2012. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283520077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malliani A, Pagani M, Lombardi F, Cerutti S. Cardiovascular neural regulation explored in the frequency domain. Circulation 84: 482–492, 1991. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.84.2.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandle CL, Jacobs SC, Arcari PM, Domar AD. The efficacy of relaxation response interventions with adult patients: a review of the literature. J Cardiovasc Nurs 10: 4–26, 1996. doi: 10.1097/00005082-199604000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mano T, Iwase S, Toma S. Microneurography as a tool in clinical neurophysiology to investigate peripheral neural traffic in humans. Clin Neurophysiol 117: 2357–2384, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matthews KA, Woodall KL, Allen MT. Cardiovascular reactivity to stress predicts future blood pressure status. Hypertension 22: 479–485, 1993. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.22.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meuret AE, Wilhelm FH, Ritz T, Roth WT. Feedback of end-tidal Pco2 as a therapeutic approach for panic disorder. J Psychiatr Res 42: 560–568, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meuret AE, Wilhelm FH, Roth WT. Respiratory biofeedback-assisted therapy in panic disorder. Behav Modif 25: 584–605, 2001. doi: 10.1177/0145445501254006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oneda B, Ortega KC, Gusmão JL, Araújo TG, Mion D Jr. Sympathetic nerve activity is decreased during device-guided slow breathing. Hypertens Res 33: 708–712, 2010. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park J, Marvar PJ, Liao P, Kankam ML, Norrholm SD, Downey RM, McCullough SA, Le NA, Rothbaum BO. Baroreflex dysfunction and augmented sympathetic nerve responses during mental stress in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. J Physiol 595: 4893–4908, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP274269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parker P, Celler BG, Potter EK, McCloskey DI. Vagal stimulation and cardiac slowing. J Auton Nerv Syst 11: 226–231, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(84)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Proietti R, Mapelli D, Volpe B, Bartoletti S, Sagone A, Dal Bianco L, Daliento L. Mental stress and ischemic heart disease: evolving awareness of a complex association. Future Cardiol 7: 425–437, 2011. doi: 10.2217/fca.11.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.R Development Core Team R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016. https://www.r-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Radaelli A, Raco R, Perfetti P, Viola A, Azzellino A, Signorini MG, Ferrari AU. Effects of slow, controlled breathing on baroreceptor control of heart rate and blood pressure in healthy men. J Hypertens 22: 1361–1370, 2004. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000125446.28861.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosaura Polak A, Witteveen AB, Denys D, Olff M. Breathing biofeedback as an adjunct to exposure in cognitive behavioral therapy hastens the reduction of PTSD symptoms: a pilot study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 40: 25–31, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s10484-015-9268-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rudas L, Crossman AA, Morillo CA, Halliwill JR, Tahvanainen KU, Kuusela TA, Eckberg DL. Human sympathetic and vagal baroreflex responses to sequential nitroprusside and phenylephrine. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H1691–H1698, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Samuelsson RG, Nagy G. Effects of respiratory alkalosis and acidosis on myocardial excitation. Acta Physiol Scand 97: 158–165, 1976. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1976.tb10248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schein MH, Gavish B, Baevsky T, Kaufman M, Levine S, Nessing A, Alter A. Treating hypertension in type II diabetic patients with device-guided breathing: a randomized controlled trial. J Hum Hypertens 23: 325–331, 2009. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schein MH, Gavish B, Herz M, Rosner-Kahana D, Naveh P, Knishkowy B, Zlotnikov E, Ben-Zvi N, Melmed RN. Treating hypertension with a device that slows and regularises breathing: a randomised, double-blind controlled study. J Hum Hypertens 15: 271–278, 2001. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seals DR, Suwarno NO, Dempsey JA. Influence of lung volume on sympathetic nerve discharge in normal humans. Circ Res 67: 130–141, 1990. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.67.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seppälä EM, Nitschke JB, Tudorascu DL, Hayes A, Goldstein MR, Nguyen DT, Perlman D, Davidson RJ. Breathing-based meditation decreases posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in U.S. military veterans: a randomized controlled longitudinal study. J Trauma Stress 27: 397–405, 2014. doi: 10.1002/jts.21936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharma M, Frishman WH, Gandhi K. RESPeRATE: nonpharmacological treatment of hypertension. Cardiol Rev 19: 47–51, 2011. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181fc1ae6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sundlöf G, Wallin BG. The variability of muscle nerve sympathetic activity in resting recumbent man. J Physiol 272: 383–397, 1977. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp012050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vallbo AB, Hagbarth KE, Torebjörk HE, Wallin BG. Somatosensory, proprioceptive, and sympathetic activity in human peripheral nerves. Physiol Rev 59: 919–957, 1979. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.4.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Hateren KJ, Landman GW, Logtenberg SJ, Bilo HJ, Kleefstra N. Device-guided breathing exercises for the treatment of hypertension: an overview. World J Cardiol 6: 277–282, 2014. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i5.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wahbeh H, Goodrich E, Goy E, Oken BS. mechanistic pathways of mindfulness meditation in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychol 72: 365–383, 2016. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wallin BG, Fagius J. Peripheral sympathetic neural activity in conscious humans. Annu Rev Physiol 50: 565–576, 1988. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weathers FW, Marx BP, Friedman MJ, Schnurr PP. Posttraumatic stress disorder in DSM-5: new criteria, new measures, and implications for assessment. Psychol Inj Law 7: 93–107, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s12207-014-9191-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wehrwein EA, Orer HS, Barman SM. Overview of the anatomy, physiology, and pharmacology of the autonomic nervous system. Compr Physiol 6: 1239–1278, 2016. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang PZ, Tapp WN, Reisman SS, Natelson BH. Respiration response curve analysis of heart rate variability. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 44: 321–325, 1997. doi: 10.1109/10.563302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]