Abstract

Infection with seasonal influenza A virus (IAV) leads to lung inflammation and respiratory failure, a main cause of death in influenza-infected patients. Previous experiments in our laboratory indicate that Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) plays a substantial role in regulating inflammation in the respiratory region during acute lung injury in mice; therefore, we sought to determine if blocking Btk activity has a protective effect in the lung during influenza-induced inflammation. The Btk inhibitor ibrutinib (also known as PCI-32765) was administered intranasally to mice starting 72 h after lethal infection with IAV. Our data indicate that treatment with the Btk inhibitor not only reduced weight loss and led to survival, but also had a dramatic effect on morphological changes to the lungs, in IAV-infected mice. Attenuation of lung inflammation indicative of acute lung injury, such as alveolar hemorrhage, interstitial thickening, and the presence of alveolar exudate, together with reduced levels of the inflammatory mediators TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, KC, and MCP-1, strongly suggests amelioration of the pathological immune response in the lungs to promote resolution of the infection. Finally, we observed that blocking Btk specifically in the alveolar compartment led to significant attenuation of neutrophil extracellular traps released into the lung in vivo and neutrophil extracellular trap formation in vitro. Our innovative findings suggest that Btk may be a new drug target for influenza-induced lung injury, and, in general, that immunomodulatory treatment may be key in treating lung dysfunction driven by excessive inflammation.

Keywords: acute lung injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, influenza, neutrophil

INTRODUCTION

In the developed world, infection with seasonal influenza A virus (IAV) accounts for the majority of deaths associated with pneumonia. Pandemic strains can cause even higher mortality, e.g., the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, where influenza infection was ranked ninth among leading causes of deaths in the United States. Impaired gas exchange, bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, and hypoxemia frequently accompany severe infections with IAV and are characteristic of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (reviewed in Ref. 11). In fact, respiratory failure related to ARDS is the main cause of death in influenza-infected patients (25, 30). The incidence of influenza-initiated ARDS reaches ~2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals each year. Seasonal flu can contribute to as much as 4% of hospitalizations due to respiratory failure (22). There are limited drugs available to treat influenza infection, and emerging data suggest increasing IAV resistance to those currently approved (31). More recently, immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory therapies have shown protective effects in animal models, and some have been considered for clinical use (1, reviewed in Ref. 23). Reports indicate that IAV infection promotes rapid recruitment of neutrophils or polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) to the lower respiratory tract and alveolar compartment. In fact, numbers of neutrophils are significantly increased in nasal secretions and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in influenza-infected patients. Neutrophils are critical for effective immune response to influenza infection (28). However, these cells may also directly elicit severe complications, as observed in many patients with influenza (4, 5), and recent studies indicate that aberrant and/or excessive activation of neutrophils decreases survival and substantially enhances susceptibility to subsequent bacterial infections (2, 5, 24).

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk), a member of the Tec family of nonreceptor intracellular kinases, is most commonly known as a critical regulator of B cell development and a target for intervention in various B cell malignancies. Btk is also expressed in other cells, most notably multiple myeloid cell types, and has been increasingly associated with autoimmune disorders and innate immunity. The inactive form of Btk resides in the cytosol; upon activation, however, it is recruited to the cell membrane, where it participates in downstream signal cascades (reviewed in Ref. 16). In human neutrophils, Btk mediates signaling via Toll-like receptor-4, and previous experiments in our laboratory indicate that Btk plays a substantial role in regulating innate inflammation in the respiratory region during acute lung injury (ALI) and that this damaging inflammation is largely neutrophil-driven (13–15). We therefore hypothesized that blocking Btk might mitigate influenza-induced inflammation.

Ibrutinib (also known as PCI-32765), is a small-molecule inhibitor of Btk that functions by covalently bonding with a cysteine residue within the Btk active site, causing irreversible inhibition. This inhibitor is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of multiple B cell lymphomas, as well as chronic graft vs. host disease (16, 17). In this study we employed this Btk inhibitor in a mouse model of IAV-induced ALI to determine whether blocking Btk could convey protection via modulation of pathogenic inflammation.

METHODS

Animal experiments.

All studies involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler and conform to National Institutes of Health guidelines. Briefly, age- and sex-matched C57BL/6J mice were purchased from a single supplier (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and housed under identical conditions. All mice were 7–8 wk old and weighed 16.8–19.9 g [18.1 ± 0.9 (SD) g] when infected. Mice were infected intranasally with a lethal dose (2.7 × 102 50% chicken embryo infectious dose) of mouse-adapted H1N1 A/PR/8/34 influenza virus (10) (VR-95, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) and then randomly assigned to two groups. At 3 days after infection, mice began receiving daily treatment with PBS or Btk inhibitor/ibrutinib (PCI-32765, Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX) at 2.6 mg/kg administered intranasally, the median effective dose previously determined for mice (3). Mice were monitored daily for signs of severe distress, such as labored breathing and immobility. For the survival study, animals were weighed daily until death; alternatively, mice that lost >30% of their initial body weight were euthanized and counted as dead. In a second experiment, mice were infected and treated as described above and euthanized on day 7 of infection, lung tissue was analyzed by CT, and lung volume was measured using an eXplore Locus μ-CT Scanner (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) equipped with MicroView v2.2 software (Parallax Innovations, Ilderton, ON, Canada). Briefly, the “region grow” tool was used to select an area to represent functional lung space within the region of interest; based on this selection, a threshold was applied to the remaining region. Areas falling within the threshold that met criteria for connectivity were combined digitally to generate a functional lung volume. CT scans and volume measurements were performed by institutional core staff. Additionally, BAL fluid was collected for analysis of protein concentration, total white blood cell (WBC) count, and proportion of PMNs. Total WBCs were counted and stained with Wright-Giemsa differential stain, and PMNs were counted. PMNs were identified by characteristic morphology, such as relative cell size and nucleus shape. The largest lobe was fixed for histology, and the remaining lobes were homogenized for ELISA of concentrations of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and KC and MCP-1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Histological evaluation of lung tissue.

Lung tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and histopathological changes were evaluated for signs of lung injury, including alveolar hemorrhage, interstitial thickening, and presence of alveolar exudate, along with increased recruitment of WBCs. For each mouse, sections from two to three lobes were used to generate ~30–50 images for evaluation.

Neutrophil extracellular traps and Btk evaluation.

Scanning laser confocal microscopy was employed to investigate neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation in lungs of IAV-infected mice treated with Btk-specific siRNA or control siRNA, both conjugated with F(ab′)2 fragments of anti-neutrophil antibodies, as described previously (14). Additionally, purified mouse bone marrow or human peripheral blood neutrophils stimulated with influenza or influenza + Btk inhibitor were evaluated for NET markers. Mouse neutrophils were purified according to a previously published method (14, 32), and human neutrophils were purified as previously reported (13, 14). Lung tissue sections or purified cells were stained for the presence of matrix metalloproteinase 9 [MMP-9; catalog no. sc6840, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX; validated previously (13, 26)], citrullinated H-3 histones [CitH-3; catalog no. ab5103, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; validated previously (20)], Btk [N-20; catalog no. sc1108, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; validated previously (13–15)], or the PMN marker Ly6G (Gr-1 1A8; catalog no. 550291, BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA; validated previously (13, 18)]. Briefly, sections were incubated overnight with primary antibodies (1:100 dilution) and then for 1 h with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa 488, Alexa 568, or Alexa 647 (1:500 dilution; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Nuclei were counterstained using Hoechst 33342 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). Slides were imaged using the PerkinElmer UltraVIEW confocal live cell imaging system with a Nikon TE2000-S fluorescence microscope and plan apochromatic objective (numerical aperture 1.4). UltraVIEW Imaging Suite software (version 5.5.0.4) was used for image processing.

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SD (or means ± SE for weight loss data). Data were analyzed using SigmaPlot 11 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Cell count, BAL protein, and ELISA comparisons were first analyzed for normality (Shapiro-Wilk test) and equal variance (F-test). When data passed both tests, Student’s t-test was used; if data failed either test, the Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used. For weight loss analysis, two-way repeated-measures ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni’s t-test was used. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

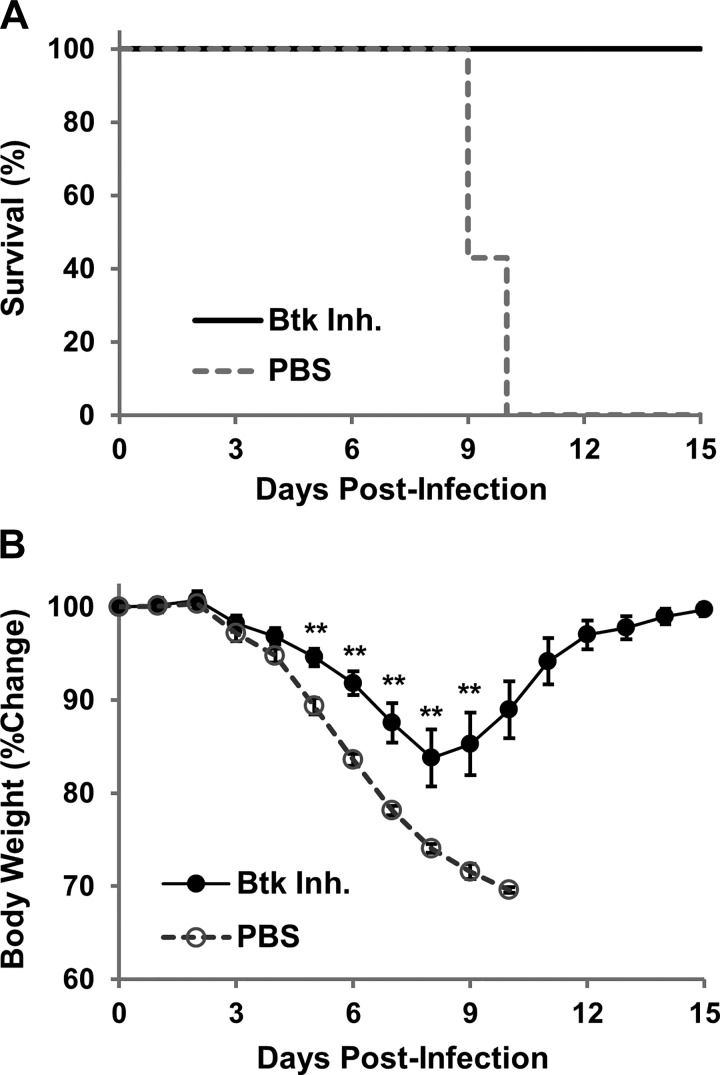

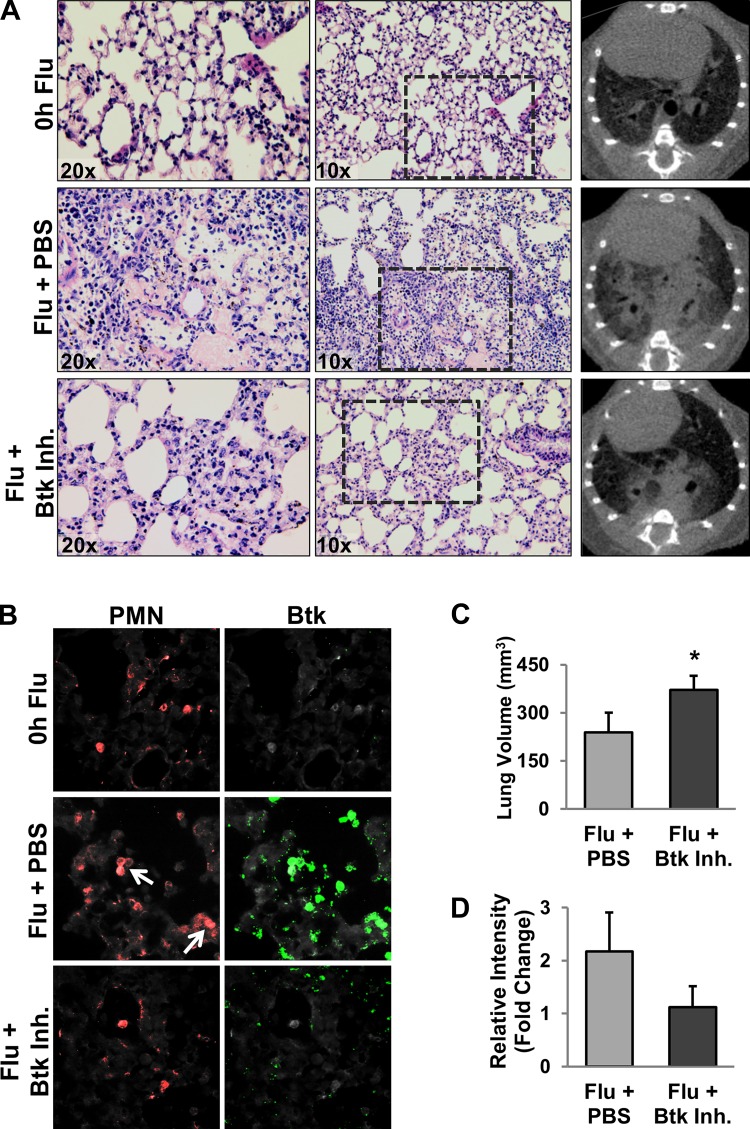

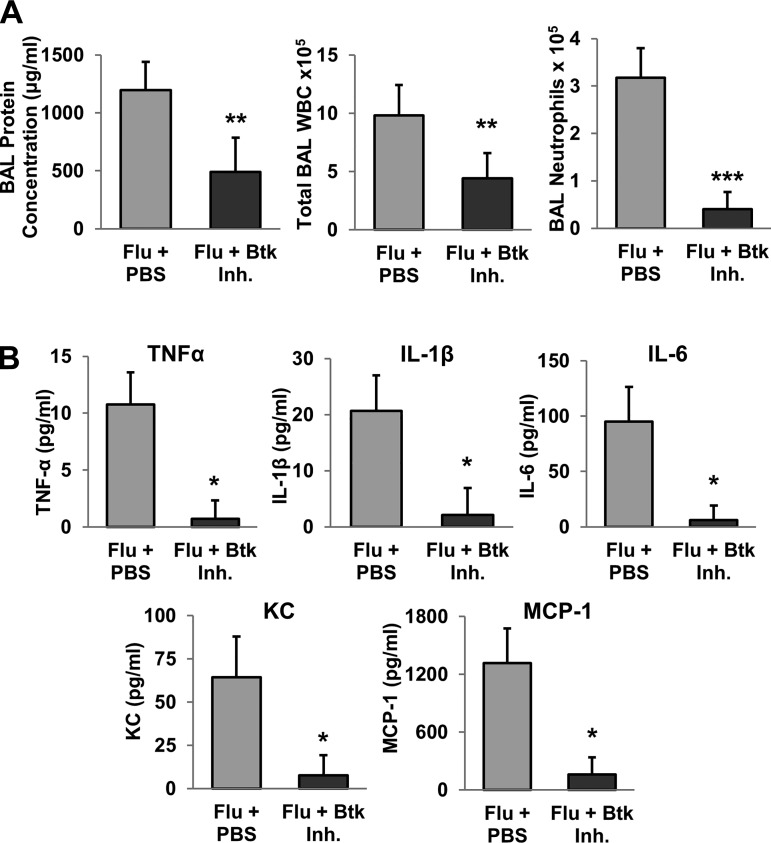

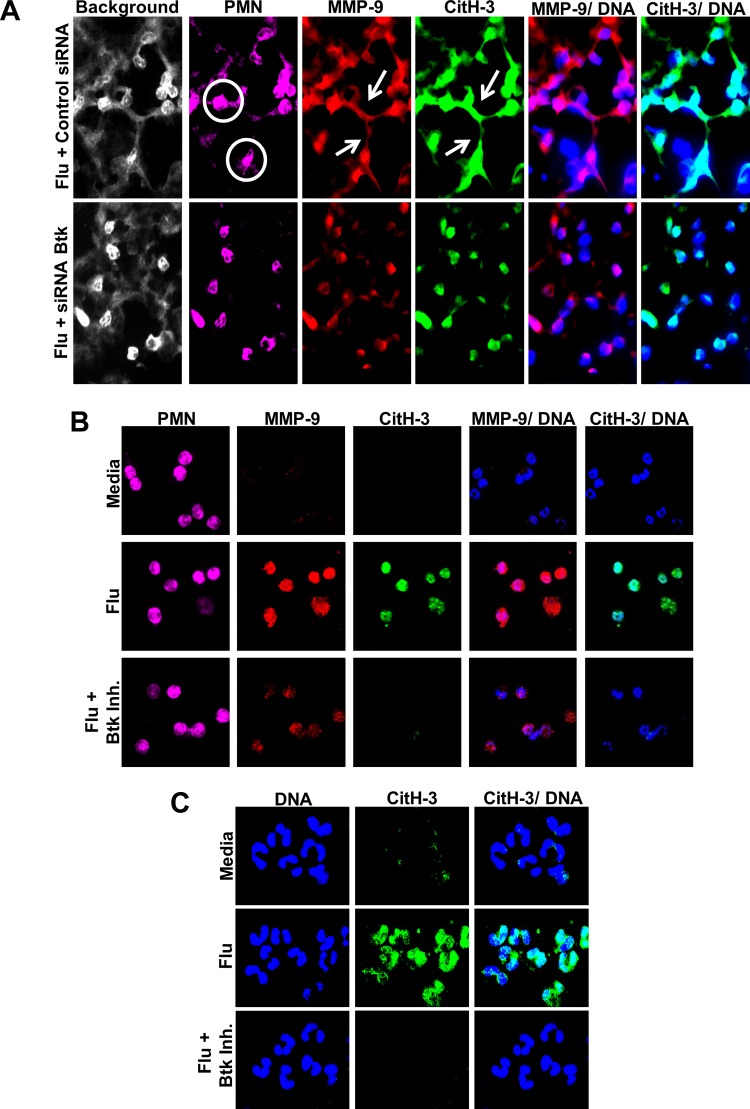

Btk inhibitor was administered intranasally to study the effectiveness of Btk targeted therapy in a mouse model of IAV-associated lung injury. Within 10 days, all mice treated with PBS died or lost >30% body weight and were euthanized (Fig. 1A): four mice died and three were euthanized. Substantial weight loss was observed in both groups starting on day 4 but was significantly less severe in Btk inhibitor-treated mice than controls (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, weight change reversed at around day 8–9 in Btk inhibitor-treated animals, and, by day 15, body weight returned its starting level. In subsequent experiments, mice were infected and treated as described above, and on day 7 postinfection, they were euthanized and lung injury was evaluated. Severe histopathological changes, such as alveolar hemorrhage, interstitial thickening, and the presence of alveolar exudate, along with evidence of increased recruitment of inflammatory cells, were observed in the lungs of PBS-treated mice relative to Btk inhibitor-treated animals (Fig. 2A, left and middle). CT analysis confirmed the protective effect in animals treated with Btk inhibitor compared with animals receiving PBS (Fig. 2A, right), i.e., reduced appearance of ground-glass opacity, a radiological observation associated with alveolar wall/septal interstitium thickening and/or alveolar accumulation of fluid, macrophages, neutrophils, or amorphous material (6). Lung abnormalities detected in CT scans were reflected in significantly higher computed lung volumes of mice receiving Btk inhibitor (Fig. 2C). Immunostaining of lung tissue from PBS-treated mice revealed increased levels of Btk, which was mitigated in the Btk inhibitor group (Fig. 2, B and D). BAL fluids were analyzed for protein concentration, total WBC count, and proportion of neutrophils, which were significantly improved in Btk inhibitor-treated mice (Fig. 3A). Inflammatory cytokines/chemokines were also measured in lung homogenates, and levels were significantly reduced following treatment with the Btk inhibitor compared with PBS-treated controls (Fig. 3B). Additionally, in separate experiments, we observed a substantial increase in MMP-9 and CitH-3 colocalized with DNA (markers of NETs) released from neutrophils in alveolar spaces of IAV-infected mice; importantly, blocking Btk in the alveolar compartment led to significant attenuation of NETs released into the lung (Fig. 4A). Histone citrullination (or deamination) is itself considered a reliable marker of NET formation (20, 33). Similar results were observed in vitro, as shown in Fig. 4, B and C. We noted an increase in NET-associated proteins in mouse bone marrow neutrophils stimulated with IAV, and colocalization between DNA and MMP-9 or between DNA and histones is clearly visible in untreated cells, indicating active NETosis. This effect was substantially downregulated in cells treated with Btk inhibitor. Images from neutrophils cultured in medium only are also presented as a corresponding control in Fig. 4B. In the same experiment performed using purified human peripheral blood neutrophils incubated with IAV, we observed an increase in CitH3 colocalized with DNA, where this effect was blunted in cells incubated with Btk inhibitor and IAV (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 1.

Survival (A) and weight loss (B) of C57BL/6 mice infected intranasally with influenza A virus (A/PR/8/34). Starting 3 days after infection, mice were treated daily with PBS (n = 7) or Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) inhibitor (Inh, n = 10) administered intranasally. Animals were monitored until death (4 mice) or weight loss of >30%, at which point they were euthanized and counted as dead (3 mice). Values for weight loss are means ± SE. Statistical significance of weight loss for days 4–9 of PBS-treated mice (n = 7) and Btk inhibitor-treated mice (n = 10) was determined by 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni’s t-test: **P < 0.01.

Fig. 2.

A: representative hematoxylin-eosin-stained lung sections (left and middle) and CT images (right) from mice 7 days after influenza A virus (Flu) infection [n = 10 and 5 mice for PBS- and Btk inhibitor (Inh)-treated groups, respectively]. B: representative images of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) in lungs of influenza A virus-infected mice. Tissue sections were analyzed by immunofluorescent staining for Btk and a PMN marker (Ly6G 1A8). White arrows indicate Ly6G/Btk double-positive cells; note differences in Btk staining between PBS- and Btk inhibitor-treated groups. C: lung volume derived from CT data (n = 10 and 5 mice for PBS- and Btk inhibitor-treated groups, respectively). Values are means ± SD; n = 3 mice in each group. *P < 0.05 (by Mann-Whitney rank sum test). D: average intensity of Btk staining expressed as fold change over control. Values are means ± SD; n = 3 mice in each group.

Fig. 3.

A: bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) protein concentration, total white blood cell (WBC) count, and number of neutrophils in BAL fluids at 7 days after influenza A virus (Flu) infection. Values are means ± SD; n = 10 and 4 mice for PBS- and Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk) inhibitor (Inh)-treated groups, respectively, for BAL protein concentration and 10 and 5 mice for PBS- and Btk inhibitor-treated groups, respectively, for cell counts. **P < 0.01 (by Mann-Whitney rank sum test); ***P < 0.001 (by Student’s t-test). B: inflammatory cytokine/chemokine concentrations in lung homogenates from mice at 7 days after influenza A virus infection. Values are means ± SD; n = 10 and 5 mice for PBS- and Btk inhibitor-treated groups, respectively. *P < 0.001 (by Student’s t-test).

Fig. 4.

A: representative images of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in influenza virus (Flu)-infected mice. Lung tissue sections were analyzed by immunofluorescent staining for markers of NETs. White circles indicate Ly6G+ cells of interest; white arrows indicate extracellular proteins of interest. Background is included to demonstrate the presence of tissue that is otherwise absent in colored images configured for specific staining to differentiate between specific and nonspecific tissue staining. Note differences in prevalence of NETs between siRNA-Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk)- and siRNA-control-treated groups. For each group, n = 3. CitH-3, citrullinated histone-3; MMP-9, matrix metalloproteinase 9. B: NET formation in purified mouse bone marrow neutrophils stimulated with influenza. Cells were stimulated with influenza or influenza + Btk inhibitor (Inh) for 2 h at 37°C. Media served as a negative control/baseline. NET release was minimal within 2 h; expression of MMP-9 and CitH-3 increased in cells exposed to influenza A virus, and this effect was abrogated in cells pretreated with Btk inhibitor. Purified neutrophils from 6 C57BL/6 mice were pooled for analysis, and images of 130–240 cells per group were captured and evaluated. For A and B, markers of NETs were MMP-9 (red), CitH-3 (green), and DNA (blue); Ly6G (Gr-1, 1A8; magenta) served as a neutrophil-specific marker. C: histone citrullination in purified human blood neutrophils stimulated with influenza or influenza + Btk inhibitor for 2 h. An increase in CitH-3 was detected in cells exposed to influenza A virus, and this effect was abrogated in cells pretreated with the Btk inhibitor. Images represent results from 1 of 3 experiments with 3 separate blood donors.

DISCUSSION

Treatment with the Btk inhibitor ibrutinib had a dramatic effect on morphological changes in the lungs of infected mice relative to controls. These changes, such as alveolar hemorrhage, interstitial thickening, and the presence of alveolar exudate, along with evidence of increased recruitment of inflammatory cells, are indicative of ALI (10). Other signs of improved response to viral infection following Btk inhibition included decreased BAL protein levels and ground-glass opacity, suggesting that the integrity of the alveolar-capillary barrier was better maintained (10). Preservation of available lung volume and reduced levels of the inflammatory mediators TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, KC, and MCP-1 strongly suggest amelioration of the pathological immune response in the lungs, promoting resolution of the infection. Because depletion has been reported to lead to worse outcomes (19, 27, 28), there is strong evidence to support a protective role for neutrophils in early stages of lung injury (21), as well as IAV infection; however, excessive neutrophil infiltration and activation in later stages of IAV infection can have severe pathological impacts (9, 19). Our laboratory was the first to establish a connection between Btk and lung injury, and in previous publications we showed that, in neutrophils, Btk regulates MMP-9 activation, as well as apoptosis and efferocytosis (13). Furthermore, we demonstrated that MMP-9 contributes to endothelial dysfunction (7, 8). All these factors provide insight into possible mechanisms by which Btk inhibition has a protective effect in IAV-induced inflammation.

Emerging studies have shown that Btk may also regulate NLRP3 inflammasome formation and that these inflammasomes appear to be beneficial early in the host response to IAV infection but detrimental later in the course of infection (12, 29). These observations suggest another possible mechanism by which treatment of mice with a Btk inhibitor offers protection, as they display a similar dynamic, whereby the innate immune response is initially beneficial but may later increase the pathological impact and impede the resolution of severe IAV infection.

Additionally, neutrophil mechanisms that may contribute to the immunopathology of influenza infections include the release of NETs, as they contain not only antimicrobial nuclear proteins, such as citrullinated histones, but also proteolytic enzymes, including elastase, myeloperoxidase, and MMP-9 (19, 20, 33). Preliminary findings reported by our laboratory suggest that Btk may be a critical regulator of neutrophil function during the course of infection with influenza virus (15). Increased Btk was detected in lung neutrophils of IAV-infected mice. These preliminary findings indicate that treatment specifically targeting neutrophils with Btk-specific siRNA conjugated with F(ab′)2 fragments of anti-neutrophil antibodies attenuates Btk expression in lung neutrophils and protects animals from influenza-induced ALI, whereas control siRNA had a negligible effect (15).

In summary, these innovative findings suggest that Btk may be a new drug target for IAV-induced ALI/ARDS and, in general, that immunomodulatory treatment may be key in treating lung dysfunction driven by excessive inflammation. Our previous studies showed that both nonspecific and neutrophil-targeted disruption of Btk activity were beneficial in lung injury models. Moreover, our future studies aim to better understand the value of both cell-specific and broad-spectrum Btk inhibition in inflammatory disease.

GRANTS

A. K. Kurdowska received funding from Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute Grant 13016_CIA, and M. A. Matthay received funding from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-51856.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M.F., A.K., M.A.M., and A.K.K. conceived and designed research; J.M.F., A.K., L.M.B., and S.A.D. performed experiments; J.M.F., A.K., L.M.B., S.A.D., and A.K.K. analyzed data; J.M.F., A.K., L.M.B., and A.K.K. interpreted results of experiments; J.M.F. prepared figures; J.M.F., A.K., and A.K.K. drafted manuscript; J.M.F., M.A.M., and A.K.K. edited and revised manuscript; M.A.M. and A.K.K. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blanc F, Furio L, Moisy D, Yen HL, Chignard M, Letavernier E, Naffakh N, Mok CK, Si-Tahar M. Targeting host calpain proteases decreases influenza A virus infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 310: L689–L699, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00314.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandes M, Klauschen F, Kuchen S, Germain RN. A systems analysis identifies a feedforward inflammatory circuit leading to lethal influenza infection. Cell 154: 197–212, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang BY, Huang MM, Francesco M, Chen J, Sokolove J, Magadala P, Robinson WH, Buggy JJ. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 ameliorates autoimmune arthritis by inhibition of multiple effector cells. Arthritis Res Ther 13: R115, 2011. doi: 10.1186/ar3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damjanovic D, Small CL, Jeyanathan M, McCormick S, Xing Z. Immunopathology in influenza virus infection: uncoupling the friend from foe. Clin Immunol 144: 57–69, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duemmler A, Montes-Vizuet AR, Cruz JS, Terán LM. CXCL5 into the upper airways of children with influenza A virus infection. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc 48: 393–398, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engeler CE, Tashjian JH, Trenkner SW, Walsh JW. Ground-glass opacity of the lung parenchyma: a guide to analysis with high-resolution CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 160: 249–251, 1993. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.2.8424326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Florence JM, Krupa A, Booshehri LM, Allen TC, Kurdowska AK. Metalloproteinase-9 contributes to endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis via protease activated receptor-1. PLoS One 12: e0171427, 2017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Florence JM, Krupa A, Booshehri LM, Gajewski AL, Kurdowska AK. Disrupting the Btk pathway suppresses COPD-like lung alterations in atherosclerosis prone ApoE−/− mice following regular exposure to cigarette smoke. Int J Mol Sci 19: E343, 2018. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia CC, Russo RC, Guabiraba R, Fagundes CT, Polidoro RB, Tavares LP, Salgado AP, Cassali GD, Sousa LP, Machado AV, Teixeira MM. Platelet-activating factor receptor plays a role in lung injury and death caused by influenza A in mice. PLoS Pathogens 6: e1001171, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gotts JE, Abbott J, Matthay MA. Influenza causes prolonged disruption of the alveolar-capillary barrier in mice unresponsive to mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 307: L395–L406, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00110.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herold S, Becker C, Ridge KM, Budinger GR. Influenza virus-induced lung injury: pathogenesis and implications for treatment. Eur Respir J 45: 1463–1478, 2015. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00186214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito M, Shichita T, Okada M, Komine R, Noguchi Y, Yoshimura A, Morita R. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is essential for NLRP3 inflammasome activation and contributes to ischaemic brain injury. Nat Commun 6: 7360, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krupa A, Fol M, Rahman M, Stokes KY, Florence JM, Leskov IL, Khoretonenko MV, Matthay MA, Liu KD, Calfee CS, Tvinnereim A, Rosenfield GR, Kurdowska AK. Silencing Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in alveolar neutrophils protects mice from LPS/immune complex-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 307: L435–L448, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00234.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krupa A, Fudala R, Florence J, Tucker T, Allen TC, Standiford TJ, Luchowski R, Fol M, Rahman M, Gryczynski Z, Gryczynski I, Kurdowska AK. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase mediates cross-talk between FcγRIIa and TLR4 signaling cascades in human neutrophils. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 48: 240–249, 2013. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krupa A, Matthay MA, Florence JM, Kurdowska AK. Targeting Bruton’s tyrosine kinase has a protective effect in influenza A virus induced acute lung injury (Abstract). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 191: A6103, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.López-Herrera G, Vargas-Hernández A, González-Serrano ME, Berrón-Ruiz L, Rodríguez-Alba JC, Espinosa-Rosales F, Santos-Argumedo L. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase—an integral protein of B cell development that also has an essential role in the innate immune system. J Leukoc Biol 95: 243–250, 2014. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0513307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miklos D, Cutler CS, Arora M, Waller EK, Jagasia M, Pusic I, Flowers ME, Logan AC, Nakamura R, Blazar BR, Li Y, Chang S, Lal I, Dubovsky J, James DF, Styles L, Jaglowski S. Ibrutinib for chronic graft-versus-host disease after failure of prior therapy. Blood 130: 2243–2250, 2017. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-793786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohning MP, Thomas SM, Barthel L, Mould KJ, McCubbrey AL, Frasch SC, Bratton DL, Henson PM, Janssen WJ. Phagocytosis of microparticles by alveolar macrophages during acute lung injury requires MerTK. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 314: L69–L82, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00058.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narasaraju T, Yang E, Samy RP, Ng HH, Poh WP, Liew AA, Phoon MC, van Rooijen N, Chow VT. Excessive neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to acute lung injury of influenza pneumonitis. Am J Pathol 179: 199–210, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neeli I, Khan SN, Radic M. Histone deimination as a response to inflammatory stimuli in neutrophils. J Immunol 180: 1895–1902, 2008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paris AJ, Liu Y, Mei J, Dai N, Guo L, Spruce LA, Hudock KM, Brenner JS, Zacharias WJ, Mei HD, Slamowitz AR, Bhamidipati K, Beers MF, Seeholzer SH, Morrisey EE, Worthen GS. Neutrophils promote alveolar epithelial regeneration by enhancing type II pneumocyte proliferation in a model of acid-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 311: L1062–L1075, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00327.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortiz JR, Neuzil KM, Rue TC, Zhou H, Shay DK, Cheng PY, Cooke CR, Goss CH. Population-based incidence estimates of influenza-associated respiratory failure hospitalizations, 2003 to 2009. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188: 710–715, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2341OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos I, Fernandez-Sesma A. Modulating the innate immune response to influenza A virus: potential therapeutic use of anti-inflammatory drugs. Front Immunol 6: 361, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rynda-Apple A, Robinson KM, Alcorn JF. Influenza and bacterial superinfection: illuminating the immunologic mechanisms of disease. Infect Immun 83: 3764–3770, 2015. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00298-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Short KR, Kroeze EJBV, Fouchier RAM, Kuiken T. Pathogenesis of influenza-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 14: 57–69, 2014. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70286-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song G, Zong C, Zhang Z, Yu Y, Yao S, Jiao P, Tian H, Zhai L, Zhao H, Tian S, Zhang X, Wu Y, Sun X, Qin S. Molecular hydrogen stabilizes atherosclerotic plaque in low-density lipoprotein receptor-knockout mice. Free Radic Biol Med 87: 58–68, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tate MD, Brooks AG, Reading PC. The role of neutrophils in the upper and lower respiratory tract during influenza virus infection of mice. Respir Res 9: 57, 2008. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tate MD, Ioannidis LJ, Croker B, Brown LE, Brooks AG, Reading PC. Role of neutrophils during mild and severe influenza virus infections of mice. PLoS One 6: e17618, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tate MD, Ong JD, Dowling JK, McAuley JL, Robertson AB, Latz E, Drummond GR, Cooper MA, Hertzog PJ, Mansell A. Reassessing the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome during pathogenic influenza A virus infection via temporal inhibition. Sci Rep 6: 27912, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep27912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.To KK, Hung IF, Li IW, Lee KL, Koo CK, Yan WW, Liu R, Ho KY, Chu KH, Watt CL, Luk WK, Lai KY, Chow FL, Mok T, Buckley T, Chan JF, Wong SS, Zheng B, Chen H, Lau CC, Tse H, Cheng VC, Chan KH, Yuen KY. Delayed clearance of viral load and marked cytokine activation in severe cases of pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 50: 850–859, 2010. doi: 10.1086/650581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Vries E, Ison MG. Antiviral resistance in influenza viruses: clinical and epidemiological aspects. In: Antimicrobial Drug Resistance, edited by Mayers D, Sobel J, Ouellette M, Kaye K, Marchaim D. New York: Springer, 2017, p. 1165–1183, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-47266-9_23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Welch EJ, Naikawadi RP, Li Z, Lin P, Ishii S, Shimizu T, Tiruppathi C, Du X, Subbaiah PV, Ye RD. Opposing effects of platelet-activating factor and lyso-platelet-activating factor on neutrophil and platelet activation. Mol Pharmacol 75: 227–234, 2009. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.051003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu L, Liu L, Zhang Y, Pu L, Liu J, Li X, Chen Z, Hao Y, Wang B, Han J, Li G, Liang S, Xiong H, Zheng H, Li A, Xu J, Zeng H. High level of neutrophil extracellular traps correlates with poor prognosis of severe influenza A infection. J Infect Dis 217: 428–437, 2018. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]