Summary

Lateral diffusion on the neuronal plasma membrane of the AMPA-type glutamate receptor (AMPAR) serves an important role in synaptic plasticity. We investigated the role of the secreted glycoprotein Noelin1 (Olfactomedin-1 or Pancortin) in AMPAR lateral mobility and its dependence on the extracellular matrix (ECM). We found that Noelin1 interacts with the AMPAR with high affinity, however, without affecting rise- and decay time and desensitization properties. Noelin1 co-localizes with synaptic and extra-synaptic AMPARs and is expressed at synapses in an activity-dependent manner. Single-particle tracking shows that Noelin1 reduces lateral mobility of both synaptic and extra-synaptic GluA1-containing receptors and affects short-term plasticity. While the ECM does not constrain the synaptic pool of AMPARs and acts only extrasynaptically, Noelin1 contributes to synaptic potentiation by limiting AMPAR mobility at synaptic sites. This is the first evidence for the role of a secreted AMPAR-interacting protein on mobility of GluA1-containing receptors and synaptic plasticity.

Keywords: AMPAR-associated protein, glutamate receptor, receptor mobility, synapse function, synaptic plasticity

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Noelin1 interacts with high affinity to AMPA receptors (AMPARs)

-

•

Noelin1 is secreted upon cellular stimulation

-

•

(Extra)synaptic AMPAR mobility, but not channel properties, are affected by Noelin1

-

•

Reducing synaptic AMPAR lateral mobility by Noelin1 limits synaptic plasticity

Pandya et al. find that the secreted protein Noelin1 binds AMPA-type glutamate receptors with high affinity. They show a role in limiting receptor mobility and keeping receptors at synaptic sites in a subunit-specific way. This is the first evidence for a secreted auxiliary subunit in mobility and plasticity of glutamate receptors.

Introduction

Excitatory synaptic transmission in the brain largely depends on glutamate signaling involving AMPA-type glutamate receptors (AMPARs). Regulation of pre- or postsynaptic strength is a crucial element, in particular, in plasticity-dependent processes such as learning and memory (Huganir and Nicoll, 2013). Postsynaptic plasticity mechanisms, most importantly, include alterations in numbers of synaptic AMPARs and/or modulation of their biophysical properties. In recent years, several AMPAR-interacting proteins have been identified and functionally characterized. Some of these have been shown to fulfill the criteria of an auxiliary subunit. In particular, transmembrane AMPAR regulatory proteins (TARPs) (Chen et al., 2000, Tomita et al., 2004), cornichons (Schwenk et al., 2009), Shisa6 (Klaassen et al., 2016), Shisa7 (Schmitz et al., 2017), and Shisa9 (CKAMP44) (von Engelhardt et al., 2010) were shown to modify AMPAR biophysical properties, affect receptor trafficking, and/or trap receptors at the postsynaptic density (PSD).

Several auxiliary subunits critically affect aspects of lateral diffusion of the AMPAR. For instance, the C-terminal tail of TARP γ-2 and Shisa6 can bind to PSD95, and this interaction was shown to trap AMPARs at the postsynaptic density (Bats et al., 2007, Constals et al., 2015, Klaassen et al., 2016, Schnell et al., 2002). Elevated Ca2+ levels inside spines after synaptic potentiation alter the affinity of AMPAR-bound TARP to postsynaptic scaffolds. These processes might determine the numbers of surface synaptic receptors, can restrict the localization of receptors to synaptic nanodomains (MacGillavry et al., 2013, Nair et al., 2013), affect desensitization and alter short- and long-term synaptic plasticity.

Only recently, it was demonstrated that, apart from the stabilization of synaptic AMPARs involving auxiliary subunits via C-terminal intracellular interactions, the AMPAR N-terminal domain also plays a crucial role (Díaz-Alonso et al., 2017, Watson et al., 2017). This opens the possibility that secreted AMPAR-associated proteins have a role in AMPAR synaptic mobility. Here, we focused on assessing the function of the secreted glycoprotein Noelin1 (Olfactomedin-1 or Pancortin), a highly interspecies-conserved protein (Barembaum et al., 2000, Moreno and Bronner-Fraser, 2001). Noelin1 was initially identified as an AMPAR-interacting protein by subunit GluA1 immunoprecipitation of synaptosomal preparations, using GluA1 gene deletion as a control (von Engelhardt et al., 2010), which was recently validated (Chen et al., 2014, Schwenk et al., 2012, Schwenk et al., 2014). The Olfm1 gene gives rise to four alternatively spliced transcripts (noelin, a–d prescursor, or Noelin1-1, 1-2, 1-3, and 1-4) (Ando et al., 2005, Danielson et al., 1994). Immunoblots of Noelin1 in brain tissue and heterologous expression of the protein in HEK293T cells show that it forms covalently bound tetramers with a molecular weight >250 kDa (Ando et al., 2005, Pronker et al., 2015). Noelin1 interacts with the Nogo receptor (RTN4R) and is implicated in the modulation of axonal outgrowth (Nakaya et al., 2012). These and other studies have pointed to a role of Noelin1 as a regulatory extracellular signaling molecule. However, the role that Noelin1 plays in AMPAR regulation has remained largely unexplored. Here, using biochemical, electrophysiological, and cellular imaging approaches, we identify a role of Noelin1 in the mobility of GluA1-containing AMPARs and short-term plasticity.

Results

Noelin1 Is Part of a Stable Complex with the AMPAR and TARP γ-8

AMPAR immunoprecipitations (IPs) have repeatedly identified Noelin1 as an AMPAR-interacting protein (von Engelhardt et al., 2010, Nakaya et al., 2012, Schwenk et al., 2012). The Olfm gene is highly expressed throughout the brain, predominantly in the hippocampus and cortex (Figure S1). We find Noelin1 present in synaptosomal and synaptic hippocampus membrane fractions and particularly enriched in the Triton X-100 insoluble postsynaptic density fraction (Figure 1A). To establish the molecular composition of the Noelin1-AMPAR complex, we first determined whether the Noelin1-AMPAR complex contained other AMPAR-interacting proteins. We used a specific Noelin1 antibody and performed IP followed by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis of the hippocampal P2 + microsome fraction. Examining the list of potential interacting proteins of Noelin1 for currently known AMPAR-interacting proteins (Schwenk et al., 2012, Schwenk et al., 2014) reveals that, apart from AMPAR subunits GluA1, -2, and -3, the Noelin1 IP also contains TARP γ-8 and Neuritin (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Noelin1 Is PSD Enriched and Interacts with AMPAR Subunits

(A) Biochemical fractions—homogenate (H), microsomes (M), crude synaptic membranes (P2), synaptosomes (SS), synaptic membranes (SM), and postsynaptic density fraction (PSD; Triton X-100 insoluble)—of mature mouse hippocampus analyzed for specific markers.

(B) Immunoblot (IB) analysis of native hippocampal immunoprecipitated GluA2/3 complexes versus peptide blocking (PB) control (left) and of immunoprecipitated Noelin1 complexes in the Noelin1 IP versus the PB control (right). Since Noelin1-2 runs at the same height as the antibody light chain (25 kDa), a clear enrichment remains inconclusive; this Noelin1 form was not tested in further experiments.

(C) Heterologous expression (HEK293T cells) of individual Noelin1 isoforms (see Figures S1 and S2) with the GluA2 subunit. The molecular weight (in kilodaltons) is indicated. For full blots, see Figure S8. For full Noelin-1 native hippocampal IP, see Table S1.

See also Figures S1, S2, and S8 and Table S1.

The Noelin1 transcripts generate protein isoforms sharing the M region, with isoforms 1-1 and 1-3 specifically containing the olfactomedin domain (Figure S1). AMPAR IPs in the hippocampus revealed peptides with sequences mapping to the olfactomedin domain and the common M region. Thus, none of these were unique to a specific Noelin1 splice variant (Figure S1). To determine which specific isoform of Noelin1 interacts with the AMPAR, we performed IPs using an antibody directed to both GluA2 and GluA3 in the absence and presence of a peptide epitope block (Chen et al., 2014) followed by immunoblotting. This revealed the interaction of Noelin1-1, 1-3, and 1-4 with GluA2- and GluA3-containing receptors (Figure 1B), with the highest abundance of Noelin1-3 and Noelin1-4. Reverse IP using the Noelin1 antibody revealed the presence of the Noelin1-1, 1-3, and 1-4 isoforms in the IP, along with GluA2- and GluA3-containing receptors, compared to a peptide epitope blocking control (Figure 1B). Together, these data demonstrate that Noelin1 isoforms predominantly form a stable complex with TARP γ-8-containing AMPARs, with Noelin1-3 being the most abundant isoform associated with the AMPAR in the hippocampus.

Having established that Noelin1 and the AMPAR can be part of one protein complex, we determined whether the interaction between the AMPAR and Noelin1 is direct or enabled by other neuronal accessory proteins. GluA1 and GluA2 AMPAR subunits were co-expressed with Noelin1-1::EGFP, and untagged Noelin1-3 and Noelin1-4 in HEK293T cells, and GluA1 and GluA2 IPs were performed. Immunoblotting for Noelin1 (Figure 1C; Figure S2) shows protein bands corresponding to Noelin11, 1-3, and 1-4 in both GluA2 and GluA1 IPs that were absent in controls. This indicates that Noelin1 directly interacts with the AMPAR, without the necessity of additional neuronal expressed proteins. Furthermore, all three Noelin1 isoforms can bind with both GluA1 and GluA2 subunits of the AMPAR, and no isoform specificity in AMPAR binding was observed.

Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor Analysis Reveals a Noelin1 Oligomerization-Dependent Interaction with the AMPAR

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensor technology was used to characterize the interaction between Noelin1-3 and the AMPAR and to determine the kinetic rate constants. A C-terminal GluA2 antibody was covalently immobilized on two biosensor surfaces, referred to as the “receptor surface” and “control surface,” and an n-dodecyl β-D-maltoside-solubilized GluA2 AMPAR was subsequently captured on the receptor surface (Figure S2). Noelin1-3, obtained from transfected HEK293T cells after ultrafiltration (Figure S2), was subsequently injected over both the receptor and control surfaces in 2-fold dilution series (0.45 nM–7.2 nM), and a specific interaction with GluA2 AMPARs was recorded (Figure 2A). The apparent association and dissociation rate constants were determined by using a reversible 1-step interaction model for kon = 2 ⋅ 106 Ms−1 (pkon = −6.3 ± 0.1; n = 5) and koff = 2 ⋅ 10−3 s−1 (pkoff = 2.6 ± 0.1; n = 5), which corresponds to an affinity of KD (dissociation constant) = 1 ⋅ 10−9 M. Control experiments with samples from non-transfected HEK293T cells were performed under the same conditions as for Noelin1-3, and no interaction was detected (Figure 2A). These results confirm that Noelin1-3 interacts directly, and with high affinity, with the AMPAR.

Figure 2.

Noelin1-3 Interacts Directly with the AMPAR GluA2 Subunit

(A) Sensorgrams (SPR analysis) from interaction of medium containing Noelin1-3 (black lines) and from medium of non-transfected HEK293T (negative control; gray lines) with surface-immobilized GluA2 (see Figure S2). A reversible 1-step model was fitted to the double-referenced experimental data (green lines).

(B) Double-referenced sensorgrams from the interaction of Noelin1-3 with GluA2 under non-reducing (blue, cycles 10 and 28) and reducing (red, cycles 19 and 37) conditions.

(C) Bar chart of binding levels upon injection of 7 nM Noelin1-3 over the GluA2 AMPAR surfaces in the absence (blue) and presence of 1 mM DTT (red), extracted from sensorgrams displayed in (B) (black dots), with the respective cycles (in parentheses).

(D) 1D BN-PAGE IB for Noelin1 (hippocampus P2 + M fraction) extracted by 1% and 2% DDM, respectively. For SPR controls, see Figure S2; for full blots, see Figure S8.

(E) Mass spectrometry identified cross-linked tryptic peptides of the GluA2 AMPAR (W277-K294) and Noelin1 (L225-K240); cross-linked lysine residues (Gria2, K283; Noelin1, K229; red). The chemical crosslink (red line) between the olfactomedin domain of Noelin1 and the AMPAR N-terminal domain (NTD) is depicted in the 3D structure models of a GluA2 homomer (blue; PDB: 5KBS) (Twomey et al., 2016) and the Noelin1 olfactomedin domain homodimer (green; PDB: 5AMO) (Pronker et al., 2015). Note: the orientation of Noelin1 at the AMPAR cannot be well predicted and is an impression.

(F) Top view on the NTD GluA2 homomer (2 subunits, light blue; 2 subunits dark blue) in an occupancy analysis using the DisVis web server (van Zundert et al., 2017) showing a volume (pink) that gives a normalized indication of how frequently a grid point is occupied by Noelin1. The accessible interaction space (i.e., the space containing all possible protein complex conformations) was calculated, assuming a maximal Cα-Cα distance of 23.4 Å between K283 and K229 of Gria2 and Noelin1, respectively.

See also Figures S2 and S8.

As Noelin1 is known to form oligomers via disulfide bridges present in the common M region of Noelin1 (Ando et al., 2005) (Figure S1), we investigated whether Noelin1 oligomerization (Figure S2) has an important role in interaction with the AMPAR. Noelin1-3 was injected over the GluA2 AMPAR-coated surface in the presence and absence of 1 mM DTT. Noelin1-3 was not seen to interact with the GluA2 AMPAR under reducing conditions (Figure 2B; Figure S2), whereas the interaction was detected under non-reducing conditions (Figure 2B). To control for potential loss of GluA2 AMPAR functionality due to the injection of DTT, Noelin1-3 was injected alternatively in the presence and absence of DTT. Immobilized GluA2 AMPAR was not affected by the injection of DTT over the sensor surface, and the observed loss of binding under reducing conditions was specific for Noelin1-3 (Figures 2B and 2C). These data support the observation that Noelin1 can form disulfide-linked homo-tetramers (Pronker et al., 2015). We then established whether Noelin1 is capable of forming high-molecular-weight complexes with the AMPAR in vivo. Indeed, a particularly high-molecular-weight complex (ranging from 400 to 1,200 kDa) was observed in Noelin1 protein complexes from the hippocampus when separated by blue native (BN-)PAGE (Figure 2D). Lastly, we detected the presence of a peptide pair of Noelin1 and GluA2 in a disuccinimidyl sulfoxide (DSSO) crosslinked hippocampal synaptosome fraction (Figure 2E). The detection of this peptide pair reveals the close vicinity of Noelin1 and the AMPAR in vivo, indicating that a naturally occurring protein interaction between these two likely involves the N-terminal domain (NTD) of the AMPAR and the olfactomedin domain of Noelin1 (Figures 2E and 2F).

Noelin1 Does Not Affect AMPAR Conductance and Desensitization Properties

Since Noelin1 and AMPARs are partners of the same hippocampal protein complex and interact in vitro, we examined whether Noelin1 can affect the biophysical properties of AMPARs. We examined main AMPAR properties that were previously shown to be affected by other AMPAR-interacting proteins (Klaassen et al., 2016). AMPAR-mediated currents were measured in response to fast glutamate applications in the presence and absence of Noelin1 co-expressed in, or incubated with, HEK293T cells. Neither co-expression nor addition of Noelin1 and the GluA1 subunits altered homomeric GluA1 AMPAR currents (rise time, decay time, rectification) induced by a 1-ms glutamate application (Figure S3). We next assessed whether Noelin1 altered the biophysical properties of GluA1/2 heteromeric AMPARs. Upon addition of Noelin1, we did not observe differences in rise time (p = 0.943; Figure 3A), decay time (p = 0.948; Figure 3B), or recovery from desensitization (p = 0.944) (Figure 3C). Noelin1 did not alter the rectification properties of heteromeric AMPARs (Figure 3C). Thus, Noelin1 does not affect major channel conductance or kinetic properties of AMPARs.

Figure 3.

Noelin1 Has No Effect on AMPAR Channel Properties

(A) Peak-scaled example traces of whole-cell recording from HEK293T cells (Figure S3) expressing heteromeric GluA1/2-containing AMPAR channels in the absence (black) or presence (red) of Noelin1. Currents were evoked by direct application of 1 mM glutamate during 1 ms.

(B) Bar graphs (mean ± SEM) summarize the effect of the addition of Noelin1-3 on rise time and decay time of AMPAR currents.

(C) Recovery of desensitization (two consecutive 1-ms glutamate applications with inter-pulse intervals of 20, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 750, and 1,000 ms) from HEK293T cells expressing a heteromeric AMPAR channel in the absence (black) or presence (red) of Noelin1-3. Insets indicate rectification (left), and recovery of desensitization.

See also Figure S3.

Subcellular Localization of Noelin1, Its Dependence on ECM, and Its Regulation by Activity

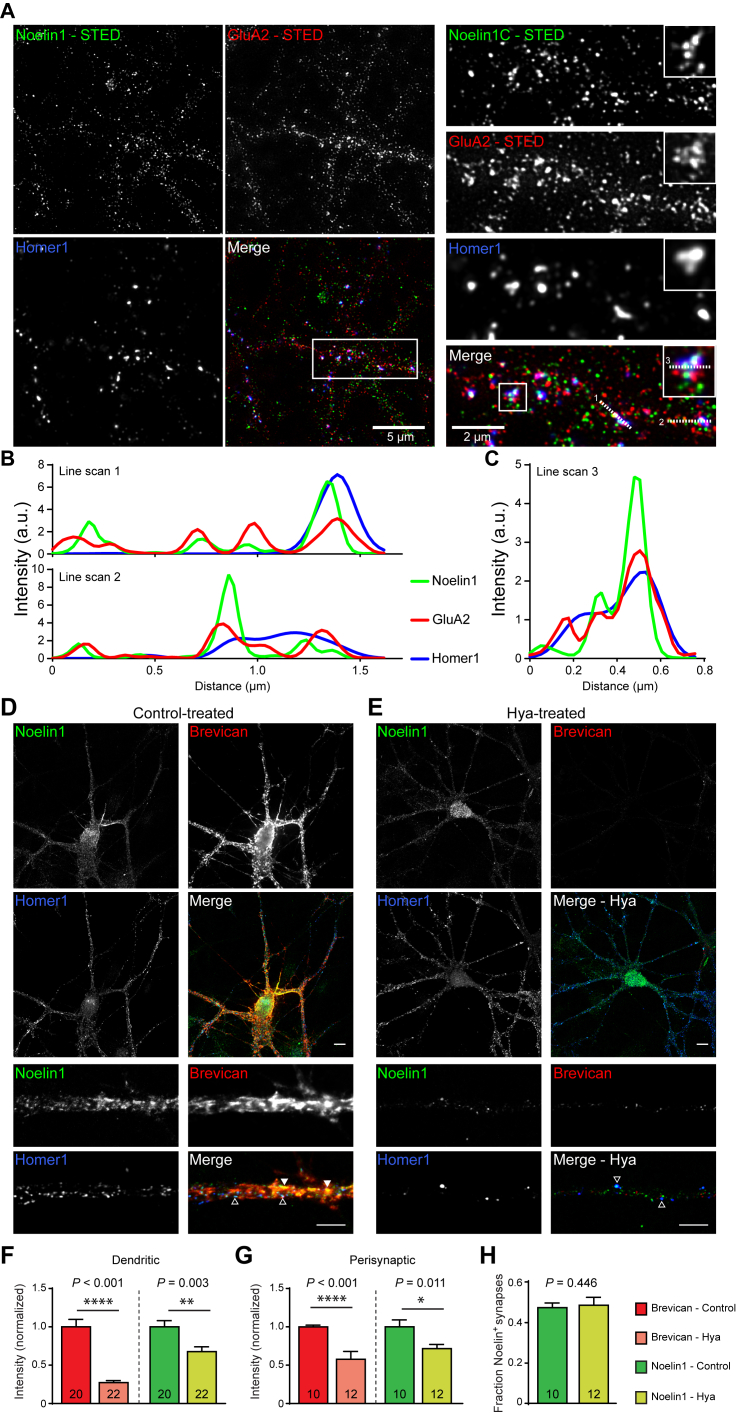

Using stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, we first determined whether Noelin1 is co-localized with AMPARs on hippocampal primary neurons (Figure 4A). Quantification of line scans across different segments on dendrites and synapses (Figures 4B and 4C) revealed that Noelin1, indeed, overlaps with AMPAR and Homer1 spots along the dendrites, inside and outside Homer1-positive puncta (Figure 4A). Line scans of dendritic spines showed colocalization of Noelin1 and GluA2 with Homer1-positive puncta (Figure 4C). Taken together, the interaction of GluA2 and Noelin1 is largely synaptic and, to some extent, extrasynaptic. This is in accordance with biochemical fractionation (cf. Figure 1A) and the distribution of TARP γ-8 over synaptic as well as extrasynaptic sites (Fukaya et al., 2006). Furthermore, we observed Noelin1 outside of GluA2 and Homer1 puncta, and this extrasynaptic Noelin1 frequently co-localizes with the extracellular matrix (ECM) marker Brevican (Figure S4).

Figure 4.

Noelin1 Is Enriched at Extrasynaptic and Postsynaptic Sites of Hippocampal Neurons, Where It Colocalizes with the AMPAR and Brevican

(A) STED imaging in DIV21 cultured hippocampal neurons show overview or zoom-ins of dendrites (right) or spines (right, inset). Permeabilized stainings of Noelin1 (green), GluA2 (red), and Homer1 (blue, synaptic marker) are shown (Figure S4). Merge shows color-overlay images. Scale bars are indicated. Inset shows a 2-fold enlargement.

(B and C) Line scans over dendrite (1 and 2) and spines (3) are displayed in (B) and (C), respectively. Numbered dashed white lines on the overlay image indicate locations of line scans across the three channels (x axis: distance, in microns; y axis: intensity in a.u.). Graphs illustrate co-enrichment of immunofluorescence intensities.

(D and E) Confocal imaging in DIV21 cultured hippocampal neurons untreated (Con; D) or treated marker Homer1 (blue), and surface staining of the ECM marker Brevican (red), are shown (for soma and dendrites in upper panels, scale bars represent 10 μm; for zoom-in of dendrites in lower panels, scale bars represent 1 μm). Colocalization of Noelin1 and Brevican (closed arrowheads), and Noelin1 and Homer1+ puncta (open arrowheads).

(F) Quantification of the total dendritic intensity of Brevican and Noelin1.

(G) Quantification of perisynaptic Brevican and Noelin1 intensity.

(H) Quantification of the fraction of Homer1 particles positive for Noelin1.

See also Figure S4.

Apart from transmembrane auxiliary subunits of the AMPAR, the extracellular matrix (ECM) alters membrane receptor lateral diffusion and thereby affects short-term synaptic plasticity (Frischknecht et al., 2009), as it might act as a local diffusion barrier for AMPARs on dendrites. To determine whether the localization of secreted Noelin1 is dependent on the ECM, we treated dissociated hippocampal neurons at 21 days in vitro (DIV21), a time point when the ECM is mature, with the enzyme hyaluronidase (Frischknecht et al., 2009).

As treatment with hyaluronidase drastically reduced the dendritic Brevican signal (Frischknecht et al., 2009), we hypothesized that if Noelin1 is associated with components of the ECM, Noelin1 immunoreactivity after hyaluronidase treatment should be similarly reduced. Also at the confocal level, Noelin1 immunoreactivity overlapped strongly with surface Brevican (Figure 4D) and with the postsynaptic density marker Homer1 (Figure 4D). Hyaluronidase treatment strongly reduced both Noelin1 (32.26%; p = 0.003; Figure 4E) and dendritic surface Brevican (72.75%; p < 0.001; Figure 4F) immunoreactivity. It also showed that the remaining immunoreactivity of Noelin1 was primarily perisynaptic (Figure 4G). Furthermore, the fraction of Noelin1-positive Homer1 puncta remained unchanged after hyaluronidase treatment, with Noelin1 staining remaining largely localized at Homer1-positive spots (Figures 4E and 4H).

To assess whether Noelin1 expression is modulated by synaptic activity, we induced chemical long-term potentiation (LTP) in primary cultured neurons using a 15-min treatment with 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) and bicuculline (4-AP/BIC) in DIV21 primary neurons. We measured surface GluA2 levels as a marker of LTP. Surface GluA2 level was significantly increased at synapses 1 hr after LTP induction (GluA2: 32.5% increase, p = 0.010), but not at dendrites (23.7% increase, p = 0.144). Noelin1 staining was increased at synaptic sites (Noelin1: 24.5% increase, p = 0.031; Figures 5A and 5C), as well as in dendrites (32.6% increase, p = 0.048; Figures 5A–5C), within 1 hr after LTP induction. Thus, Noelin1 expression is regulated in an activity-dependent manner and, therefore, might have a role in the accumulation and stabilization of synaptic AMPA receptors at the PSD.

Figure 5.

Chemical LTP Recruits AMPAR and Noelin1 to the Synapse

(A) Representative images of permeabilized immunostaining for Noelin1 and Homer1 and surface staining for GluA2 under basal conditions and 1 hr after stimulation with 4-AP and bicuculline (4-AP/BIC) in mature DIV21 neurons (scale bar, 20 μm).

(B and C) Bar graphs (mean ± SEM) show normalized total dendritic and synaptic Noelin1 (B) and GluA2 (C) under control conditions and 1 hr after a 15-min 4-AP/BIC stimulation.

Noelin1 Affects AMPAR Mobility

Association of Noelin1 and AMPARs yields high-molecular-weight complexes as observed after heterologous expression (Figure 2D; Figure S2). Therefore, Noelin1-AMPAR association might have a role in the mobility of AMPARs (Heine, 2012). To test this, first, AMPAR mobility depending on Noelin1 in HEK293T cells was measured using GluA2::pHluorin (Figure 6A; Figure S5) and GluA1::pHluorin (Figure S5) expression and single-particle tracking. The effect of intracellular expressed Noelin1, or Noelin1 applied extracellularly as conditioned medium, on AMPAR mobility was measured. Upon co-expression with Noelin1, the instantaneous diffusion coefficient, a measure for surface mobility of AMPARs, was decreased: log10 Dinst (Dinst) GluA2, −2.358 (4.385 × 10−3) μm2/s (interquartile range [IQR], 0.477; 6.135 × 10−3); log10 Dinst (Dinst) GluA2_Noelin1, −3.228 (5.916 × 10−4) μm2/s (IQR, 0.975; 2.00 × 10−3) (p < 0.001; Figure 6B). Similarly, the addition of Noelin1-conditioned medium significantly reduced the diffusion coefficient: log10 Dinst (Dinst) GluA2 + control, −2.128 (7.447 × 10−3) μm2/s (IQR, 0.463; 7.527 × 10−3); log10 Dinst (Dinst) GluA2 + Noelin1, −2.660 (2.187 × 10−3) μm2/s (IQR, 0.921; 4.116 × 10−3) (p = 0.002; Figure 6B). Quantification of the immobile fraction showed a significant reduction of GluA2 AMPAR mobility upon both co-expression (GluA2: 20.5 ± 1.8%; GluA2_Noelin1: 41.0 ± 4.1%; p < 0.001) and addition (GluA2 + control: 15.7 ± 1.7%; GluA2 + Noelin1: 32.5 ± 3.2%; p < 0.001) of Noelin1-conditioned medium (Figure 6C). The same effect was observed on GluA1-containing AMPARs in which a significant reduction on GluA1 mobility upon co-expression with Noelin1 (p = 0.034) was observed and a significant increase in the percentage of immobile receptors after addition of Noelin1 (p = 0.024) was found (Figure S5). Thus, Noelin1, independent of its route of delivery (i.e., co-expression or external application), has the ability to reduce AMPAR mobility in HEK293T cells.

Figure 6.

Noelin1 Regulates AMPAR Mobility in HEK293T Cells and Young Neurons

(A) Representative traces of SEP::GluA2 receptors expressed in HEK293T cells (upper panels; Figure S5) or in young neurons (DIV11–13; Figure S6) at extrasynaptic and synaptic sites (lower panels) without (control) (left) and with (right) (addition of) Noelin1-3. In the lower panels, the Homer1::dsRED signal is indicated. Scale bars, 2 μm.

(B) Boxplots of the diffusion coefficient (Dinst) for HEK293T cell expression of single particles of GluA2 (black), GluA2 co-expressed with Noelin1-3 (GluA2_Noelin1, red), GluA2 plus control medium (GluA2 + control, gray), and GluA2 plus medium containing Noelin1-3 (GluA2 + Noelin1, orange).

(C) Bar graphs indicate the proportion of immobile SEP::GluA2 particles for GluA2 versus GluA2_Noelin1.

(D) Temporal dynamics of mobility (area covered) of GluA2::pHluorin receptors in cultured hippocampal neurons (DIV11–13).

(E) Dinst for extrasynaptic mobile GluA2:: pHluorin AMPARs without and with Noelin1 incubation.

(F) Boxplots for Dinst for extrasynaptic SEP::GluA2 AMPARs without versus with Noelin1 incubation.

(G) Quantification of the immobile fraction obtained from (F). Number of cells are indicated ≥ two independent biological replicates.

See also Figures S5 and S6.

We subsequently tested the effect of the addition of Noelin1 on AMPAR mobility in primary neuronal cells. First, young primary cultured neurons (DIV11–13), which still lack a well-defined ECM, were tested (Frischknecht et al., 2009). GluA1::pHluorin and GluA2::pHluorin were expressed in primary neurons, along with Homer1::dsRed to identify synapses (Figure 6A). We observed a reduction in the mean square displacement (MSD) of extra-synaptic GluA2-containing AMPA receptors (Figures 6D and 6E). The distribution of the diffusion coefficient for extra-synaptic GluA2-containing AMPARs (Dinst) was shifted to smaller values upon treatment of primary neurons with Noelin1-conditioned medium (GluA2 + Noelin1) versus control (GluA2 + control) cells (Figure 6E). Quantification of the diffusion coefficient of mobile AMPARs showed a significant reduction upon treatment with Noelin1: log10 Dinst (Dinst) GluA2 + control, −1.878 (1.324 × 10−2) μm2/s (IQR, 0.094; 2.643 × 10−3); log10 Dinst (Dinst) GluA2 + Noelin1, −2.036 (9.204 × 10−3) μm2/s (IQR, 0.136; 3.086 × 10−3) (p = 0.001; Figure 6F). The percentage of low-mobility extra-synaptic GluA2-containing AMPARs also increased significantly after Noelin1 treatment (control: 16.9 ± 0.9%; Noelin1: 22.9 ± 1.1%; p < 0.001, unpaired t test) (Figure 6G). A similar effect in reducing the diffusion coefficient of extrasynaptic GluA1-containing AMPA receptors was observed (trend, p = 0.059; Figure S6), and a significant increase in percentage of immobile extrasynaptic GluA1-containing AMPARs was observed upon addition of Noelin1 (p = 0.020; Figure S6).

Analysis of the synaptic fraction of GluA2-containing AMPARs after Noelin1 addition showed no significant difference in the diffusion coefficients (p = 0.304) or in the percentage of the immobile fraction (p = 0.111) (Figure S6). In contrast, synaptic GluA1-containing AMPAR diffusion was significantly reduced upon Noelin1 treatment (p = 0.016), and the percentage of immobile synaptic GluA1-containing receptors showed a non-significant increase upon Noelin1 addition (p = 0.055; Figure S6). Thus, as in the ECM-free HEK293T cell environment, in a non-mature neuronal culture without a well-developed ECM, Noelin1 reduces AMPAR mobility. Notably, in neurons, we now observe AMPAR subunit specificity of the Noelin1 effect.

ECM-Dependent Noelin1 Rescues the Effect of Hyaluronidase Treatment on AMPAR Mobility

It has been shown that, for mature primary neurons (DIV21–23), the ECM exerts an inhibitory constraint on AMPAR mobility (Frischknecht et al., 2009). Because Noelin1 affects AMPAR mobility at extrasynaptic sites (GluA1 and GuA2) and synaptic sites (GluA1), we tested whether the addition of Noelin1-conditioned medium altered specifically GluA1-containing AMPAR mobility in primary neurons in which the ECM is mature. To do so, we treated primary neurons at DIV21–23 after transfection with GluA1::pHluorin and Homer1::dsRed, with Noelin1 or control medium. Single-particle tracking analysis revealed no change for extrasynaptic (p = 0.627) and synaptic (p = 0.895) GluA1-containing AMPAR mobility after Noelin1 application (Figure 7). Thus, Noelin1 is not able to change AMPAR mobility in the presence of a maturated ECM.

Figure 7.

Noelin1 Rescues the Effect of Hyaluronidase Treatment on GluA1-Containing AMPAR Mobility and PPR in Older Neurons

(A) Representative traces of GluA1::pHluorin receptors expressed in DIV21 primary neurons at extrasynaptic and synaptic locations after control (upper) or hyaluronidase (lower) treatment and subsequent incubation without (control; left) or with Noelin1-3 conditioned medium (right) (Figure S7). Scale bars represent 4 μm (or 2 μm for the zoom-ins).

(B–D) The distribution (B) and boxplot (C) of Dinst and bar graphs of the immobile fraction (D) for extrasynaptic SEP::GluA1 receptors.

(E–G) The distribution (E) and boxplot (F) of Dinst and bar graphs of the immobile fraction (G) for synaptic SEP::GluA1 receptors.

(H) Representative traces of electrically evoked AMPAR currents without and with hyaluronidase treatment and without and with addition of Noelin1 in DIV18 primary neurons.

(I) Bar graphs of paired-pulse ratio (PPR) I1/I2. Number of cells are indicated ≥ two independent biological replicates.

See also Figure S7.

To test whether the existing ECM overrules the effect of the addition of Noelin1, we used hyaluronidase treatment to remove the ECM and measured GluA1-containing AMPAR lateral diffusion. Hyaluronidase treatment (Hya) versus control treatment (Con) caused a significant increase in the extra-synaptic diffusion coefficient in neurons: log10 Dinst (Dinst) Hya + control, −1.879 (1.321 × 10−2) μm2/s (IQR, 0.285; 9.667 × 10−3); log10 Dinst (Dinst) Con + control, −2.050 (8.913 × 10−3) μm2/s (IQR, 0.360; 7.743 × 10−3) (Hya + control versus Con + control, p = 0.009; Figures 7B and 7C). The addition of Noelin1 after hyaluronidase treatment strongly reduced the extra-synaptic diffusion coefficient of GluA1-containing AMPARs: log10 Dinst (Dinst) Hya+Noelin1, −2.142 (7.211 × 10−3) μm2/s (IQR, 0.536; 9.153 × 10−3; Figures 7B and 7C). Furthermore, the observed decrease on the percentage of the immobile fraction after hyaluronidase treatment was brought to control level upon application of Noelin1 (Con + control: 29.3 ± 1.1%; Hya + control: 22.5 ± 1.6%; Hya + Noelin1: 31.7 ± 2.4%) (Con + control versus Hya + control: p = 0.002; Hya + control versus Hya + Noelin1: p = 0.005; Figure 7D). Thus, Noelin1 and the ECM are non-additive in their effects. The ECM seems to cause a maximum effect on limiting GluA1-containing AMPAR mobility that cannot be further enhanced by the addition of Noelin1.

Previously, it was shown that the diffusion coefficient of synaptic AMPARs was not significantly altered by hyaluronidase treatment (Frischknecht et al., 2009) (Figures 7D and 7E). Interestingly, neurons treated with Noelin1 after hyaluronidase treatment caused a significant decrease in the diffusion of synaptic GluA1-containing AMPARs in neurons (Figures 7D and 7E): log10 Dinst (Dinst) Hya + control, −1.92 (1.210 × 10−2) μm2/s (IQR, 0.496; 1.422 × 10−2); log10 Dinst (Dinst) Hya + Noelin1, −2.28 (5.224 × 10−3) μm2/s (IQR, 0.509; 5.971 × 10−3) (p = 0.003). Correspondingly, Noelin1 application introduced more synaptic immobile particles upon hyaluronidase treatment (Hya + control: 24.6 ± 1.8%; Hya + Noelin1: 31.50 ± 1.84%; p = 0.038) (Figure 7F). Thus, synaptic GluA1-containing AMPARs do not have saturated amounts of Noelin1 bound, and Noelin1 has the potential to alter the lateral diffusion of AMPARs. This opens the possibility that Noelin1 secretion might act on synaptic receptors to regulate these.

Since Noelin1 affects lateral diffusion of AMPARs in neurons when the ECM level is reduced, we next tested whether, under similar conditions, Noelin1 altered short-term plasticity by measuring paired-pulse ratios (PPRs) in mature neurons. In previous work, it has been shown that the PPR depends, in part, on the lateral mobility of AMPARs (Frischknecht et al., 2009, Heine et al., 2008). In agreement, we found a slight paired-pulse depression under control conditions (PPR (I1/I2): 0.84 ± 0.015), and hyaluronidase treatment significantly increased the PPR (PPR (I1/I2): 0.90 ± 0.008; p < 0.001; Figures 7H and 7I). Addition of Noelin1-conditioned medium after hyaluronidase treatment (Hya + Noelin1) reverted the effect of hyaluronidase treatment to control levels (PPR (I1/I2): 0.84 ± 0.008; p = 0.542 versus Con + control).

This effect was not carried by the presynapse, as miniature excitatory postsynaptic current frequency and amplitude in the presence and absence of Noelin1 were not different among groups (Figure S7). Similarly, a synaptotagmin uptake experiment (Kraszewski et al., 1995) did not show a difference among groups (Figure S7). Thus, Noelin1 acts at the post-synapse where Noelin1 is able to revert the effect of hyaluronidase treatment on short-term synaptic plasticity by reducing lateral mobility and, thus, reducing the exchange of desensitized synaptic AMPARs (Frischknecht et al., 2009). Therefore, we postulate that Noelin1 represents an extracellular regulator of AMPAR lateral diffusion acting in an activity-dependent manner, specifically relevant in the synaptic membrane domain devoid of ECM.

Discussion

We identified Noelin1 as a true high-affinity AMPAR-interacting protein using several independent methods, collectively indicating that Noelin1 acts as an intrinsic auxiliary subunit of AMPAR complexes in the brain (Yan and Tomita, 2012). Noelin1 is expressed in cortex, cerebellum, and hippocampus, consistent with existing in situ hybridization data (Lein et al., 2007). IP experiments on dodecyl maltoside (DDM)-extracted AMPAR complexes combined with LC-MS/MS demonstrated that Noelin1 is part of the AMPAR complex in all three brain regions (Chen et al., 2014). Hence, it might have a widely conserved role with respect to its interaction with the AMPAR across the brain, in contrast with several other AMPAR interactors, e.g., TARP γ-2 and γ8, which show brain region-specific interactions due to their differential expression (Chen et al., 2014, Schwenk et al., 2014). We find that AMPARs containing Noelin1 also comprise TARP γ-8 in the hippocampus. In addition, neuritin is abundantly present in Noelin1 IPs in hippocampus, whereas this protein is normally observed with low abundance values in GluA2/3 IPs (Schwenk et al., 2014).

An interesting observation in comparing the GluA2 and GluA2/3 and Noelin1 IPs is that neuritin is more abundant in the Noelin1 IP, suggesting that neuritin interacts via Noelin1 with the AMPAR. Further experiments are necessary to validate this observation. Noelin1 binds to the Nogo receptor (RTN4R) (Nakaya et al., 2012), and RTN4R is a receptor for CSPGs (Dickendesher et al., 2012). Thus, RTN4R might link Noelin1 to the ECM. However, we do not detect any RTN4R in our IP experiments, possibly due to the antibody interfering with the interaction site of RTN4R. Noelin1 IPs also revealed Noelin2 and Noelin3, the paralogs of Noelin1. These paralogs have a similar olfactomedin domain as Noelin1 and are also present in AMPAR IPs, suggesting that all Noelin forms form a higher-order complex with AMPARs (Sultana et al., 2014, Tomarev and Nakaya, 2009). Whether Noelin2 and Noelin3 might have roles similar to those established here for Noelin1 remains to be investigated.

We previously showed that Noelin1 is in a complex with the AMPAR (von Engelhardt et al., 2010), leaving unanswered whether this interaction is direct or mediated by other neuronal AMPAR accessory proteins. Using co-expression in HEK293T cells, we demonstrated that all Noelin1 isoforms interact directly with the AMPAR subunits GluA1 and GluA2. Thus, Noelin1 does not show subunit specificity for AMPARs in its interaction and is able to bind both GluA1- and GluA2-containing AMPARs, which comprise a large majority of the AMPAR subunits in most brain regions (Schwenk et al., 2014). The hippocampus GluA2/3 IPs demonstrated enrichment for the isoform Noelin1-3, and this isoform was also most abundantly present in the postsynaptic density fraction.

So far, AMPAR auxiliary subunits were shown to affect AMPAR kinetics and/or mobility. We tested both possibilities for Noelin1. Using a fast glutamate application system, we performed measurements on GluA1 homomers and GluA1-2 heteromers in the presence of Noelin1. In contrast to other reported AMPAR-associated proteins, e.g., TARPs, cornichon-2, and all Shisa members, we did not observe an effect on AMPAR channel properties in the presence of Noelin1. However, the interpretation of these data should be considered with caution, given that the constitution of the AMPAR with its auxiliary proteins in vivo may be quite complex in contrast to that in vitro.

Using SPR biosensor technology for real-time interaction analysis of the AMPAR showed the direct in vitro interaction between Noelin1-3 and GluA2 AMPA receptors. We have previously used a similar approach for characterizing small ligand interactions with the homo-oligomeric GABAA β3 receptor (Seeger et al., 2012), demonstrating the suitability of SPR methodology for real-time interaction studies of ligand-gated ion channels. With SPR, we determined the kinetic rate constants of the interaction by using a 1-step interaction model, showing a fast association of Noelin1 with immobilized GluA2 AMPARs on the SPR biosensor surface and forming a stable complex with low nanomolar affinity. Quantification of the kinetic rate constants for the Noelin1-GluA2 AMPAR interaction is challenging, as determining the protein concentration in the final analysis may suffer from protein lost during the sample preparation, potentially leading to an underestimation of the Noelin1 concentration. Thus, the kinetic rate constants were determined within the accuracy of the concentration determination relevant for the calculation of the kinetic analysis. In a previous study (Madeira et al., 2011), SPR was successfully combined with mass spectrometry to identify protein-protein interaction partners from brain lysates. This shows that one can obtain valuable kinetic information from non-purified protein samples. Due to the tetrameric structure of the GluA2 AMPAR and tetrameric Noelin1 (Pronker et al., 2015), their interactions are potentially more complex than is described by a 1-step interaction model. Therefore, the kinetic rate constants need to be regarded as approximations.

Noelin1 forms oligomers via disulfide bridges (Ando et al., 2005). Our data show that Noelin1 does not interact with the GluA2 AMPAR under reducing conditions (1 mM DTT), whereas the interaction is prominent under non-reducing conditions. The interaction of Noelin1 with immobilized GluA2 AMPARs was not affected by prior injections of DTT. This demonstrates that the formation of Noelin1 oligomers is a prerequisite for the interaction with GluA2 AMPARs and may argue for a role in receptor clustering. By detecting a Noelin1-AMPAR peptide pair using crosslinking mass spectrometry, it is likely that, in vivo, Noelin1 is in contact with the AMPAR NTD and may, thus, act to cluster AMPARs via the olfactomedin domain. As Noelin1 is a tetramer, it leaves the tetramerization domain (Pronker et al., 2015) of Noelin1 potentially available for other protein contacts that may aid in trapping the AMPAR-Noelin1 complex.

Noelin1 might work analogous to other extracellular (secreted) glutamate receptor binding proteins. Cerebellins (Cblns) are C1q family secreted proteins acting as transsynaptic connectors, binding simultaneously presynaptic alpha- or beta-neurexin and postsynaptic GluD2 (cerebellum) or GluD1 (forebrain) (Yuzaki, 2017), and might regulate bidirectionally the function of excitatory synapses. Cbln1 exists as a hexamer and binds the N-terminal domain of GluD2. In an analogy, one might speculate that the N-terminal tetramerization domain of Noelin1 binds proteins extending from neighboring cells or to the ECM and mediates trapping of the AMPAR. Whether Noelin1 can act as a bidirectional synaptic plasticity organizer, similar to the Neurexin/Cbln/GluD2 complex (Yuzaki, 2017), remains to be explored.

Noelin1 can form high-molecular-weight oligomers, and Noelin1 complexes were observed over a large molecular weight range using BN-PAGE. In HEK293T cells, Noelin1 had a role in receptor clustering with reduced mobility of both GluA1- and GluA2-containing AMPARs and an increase of the immobile pool of AMPARs. This reduction in mobility is not likely caused by the increase in mass, as previous experiments with antibody bound beads to the AMPAR have shown that membrane diffusion is determined predominantly by the size of the complex in the membrane and the membrane lipid fluidity (Heine, 2012), or by ECM molecules (Frischknecht et al., 2009). Most likely, the oligomeric Noelin1 clusters AMPARs into larger entities with lower membrane mobility. In agreement with the HEK293T cell data, when measuring the effect of Noelin1 on AMPAR mobility in young neurons (DIV11–13) without a well-formed ECM, Noelin1 reduced the mobility of extrasynaptic GluA1- and GluA2-containing AMPARs. For synaptic receptors, the addition of Noelin1 led to a significant reduction in mobility, in particular, in the pool of synaptic GluA1-containing AMPARs. It has been shown that Noelin1 can interact with its paralog proteins, Noelin2 and Noelin3, which are also secreted glycoproteins with a similar olfactomedin domain (Tomarev and Nakaya, 2009). Thus, in vivo, the combined effect of different (iso)forms of Noelin1 on AMPAR lateral mobility might be stronger than shown in the present study. Alternatively, Noelin1 might act differentially on synaptic receptors that are already decorated with other auxiliary proteins.

The addition of Noelin1 protein has no significant effect on GluA1-containing AMPAR lateral diffusion on dendrites in mature neurons, around which the ECM is well formed (Frischknecht et al., 2009). This is most likely due to the saturating effect of ECM in restricting AMPAR lateral mobility. Although ECM removal does not significantly increase synaptic GluA1 mobility in these mature cultures (Frischknecht et al., 2009), exogenously applied Noelin1 reduced the mobility of synaptic GluA1-containing receptors upon hyaluronidase treatment. This indicates that these receptors are, in principle, prone to Noelin1 regulation. As Noelin1 is highly expressed in the adult brain (Gonzalez-Lozano et al., 2016) and interacts with the AMPARs at the adult stage (von von Engelhardt et al., 2010, Schwenk et al., 2012), we think that the role of Noelin1 extends beyond the juvenile “low ECM” stage of development. The ECM can be locally modulated, depending on synaptic activity or disease state in the adult brain (Happel and Frischknecht, 2016, Riga et al., 2017), which would allow Noelin1-mediated modulation of plasticity under these conditions. In addition, the ECM density is well known to differ, both in components and in its density, over different brain areas. The density of the ECM in hippocampus (Lensjø et al., 2017) is low compared to other brain areas, making sense, given the lifelong neuronal network plasticity in this brain area. Furthermore, although the synapse is enwrapped in ECM, the synaptic space between pre- and postsynaptic neuron is free of ECM (Brückner et al., 2000), thereby forming a local environment in which each synapse can be differentially affected. On the other hand, the mobility of extrasynaptic GluA1-containing receptors was increased after hyaluronidase treatment, confirming previous data (Frischknecht et al., 2009), and was brought to control levels after bath application of Noelin1. Apart from affecting AMPAR lateral mobility at both synaptic and extrasynaptic sites, we showed that the addition of Noelin1 reduces the hyaluronidase-mediated increase in short-term synaptic plasticity using PPR measurements. Together, our data suggest that, in the brain, Noelin1 affects the mobility of synaptic GluA1-containing receptors but not synaptic receptors containing GluA2. Hence, we postulate that Noelin1 acts at a pool of synaptic GluA2-lacking receptors that become recruited upon repeated stimulation (Díaz-Alonso et al., 2017, Jaafari et al., 2012, Plant et al., 2006). That a synaptic GluA2, in contrast to a non-synaptic GluA2-containing receptor, cannot be influenced by Noelin1 might be due to the presence of other auxiliary proteins.

Noelin1 may contribute to the consolidation of synaptic potentiation by limiting the diffusion and exchange of AMPARs between the synaptic and extrasynaptic pools. We previously observed that Noelin1 shows a downregulation with ECM components in the dorsal hippocampus during memory consolidation (Rao-Ruiz et al., 2015), a moment when plasticity in the preparation is high. Given that Noelin1 was found colocalized with the ECM, activity-dependent remodeling of the ECM (Dityatev et al., 2010) might lead to an increase or decrease in the presentation of Noelin1 to the AMPARs on extrasynaptic sites, affecting their mobility and regulating the availability of extrasynaptic AMPARs to be exchanged with synaptic AMPARs.

It has recently been shown that the NTD of the GluA1 subunit has a crucial role in the targeting and stabilization of synaptic AMPARs (Díaz-Alonso et al., 2017). It was suggested that N-terminal potential interactions with extracellular proteins might play a role (Watson et al., 2017). Given the high affinity of Noelin1 for the AMPAR and its property to restrict lateral diffusion when added to the extracellular medium puts Noelin1 in the position of this suggested regulatory role. Structural data of Noelin1 in binding to the AMPAR should elucidate this.

Our IP data show the co-occurrence of Noelin1 and TARP γ-8. Structural data, mapping the contact sites of TARP proteins onto the AMPAR (Cais et al., 2014), showed that, extracellularly, TARP mainly contacts the AMPAR ligand-binding domain and the bottom part of the N-terminal domain. This leaves the possibility of Noelin1 binding to the upper NTD without interfering with TARP binding.

Taken together, our data show that Noelin1 is the first example of a secreted AMPAR auxiliary protein that tunes the receptor’s membrane mobility, thereby affecting short-term synaptic plasticity. Noelin1 might function in the recently described AMPAR-NTD-mediated trafficking of the receptor.

Experimental Procedures

Antibodies

Antibodies are given in Table S2.

Preparation of Subcellular Fractions and Immunoprecipitation

Hippocampus subcellular fractions (adult C57/Bl6J) were prepared as described previously (Klaassen et al., 2016), with some modifications (Supplemental Information). Affinity purification was as previously described (Chen et al., 2014).

Immunoblot Analysis

After SDS-PAGE and transfer, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes were blocked (Supplemental Information) and incubated with the primary antibody (4°C). After washing and incubation with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody, blots were prepared for chemoluminescence and scanning (Supplemental Information).

DNA Constructs

Full-length cDNA constructs for different Noelin1 isoforms and for GluA1 and GluA2 (Supplemental Information) were used.

Co-precipitation from HEK293T Cells

For extraction of proteins, HEK293T cells were washed in ice-cold PBS, scraped and resuspended in lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES; pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% DDM, protease inhibitor cocktail), and incubated for 1 hr at 4°C while gently shaking at 10 rpm. The lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatants were incubated with GluA2 antibody for 1 hr while gently shaking at 10 rpm. Post-antibody incubation, the lysates were incubated with 50 μL protein A/G beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 hr and washed three times in wash buffer (0.1% DDM), and the bound proteins were eluted off with Laemmli buffer followed by SDS-PAGE immunoblot analysis.

Primary Cultures

Primary hippocampal neurons were obtained from embryonic day (E)18 pups as described previously (Frischknecht et al., 2009). Dual-color STED data were obtained (Ivanova et al., 2015), and line scan analysis was performed (Frischknecht et al., 2009), as previously described. Chemical LTP induction was performed as previously described (Ivanova et al., 2015), with minor modifications. All experiments were performed in accordance to Dutch law and licensing agreements using protocols approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the VU University Amsterdam.

In Situ Hybridization

See http://mouse.brain-map.org/experiment/show/761, probe nrRP_040324_01_F0326 (Lein et al., 2007).

SPR Biosensor-Based Interaction Analysis

GluA2-containing AMPARs were extracted from HEK293T cell pellets using 25 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1% DDM (w/v) (Affymetrix) (pH 7.4), and one protease inhibitor tablet per 50 mL buffer (buffer S) on ice or at 4°C. Noelin1 secreted in medium after expression in HEKT293 cells (Supplemental Information) was used. Subsequent SPR-based biosensor studies were performed as described previously (Seeger et al., 2017), with minor modifications.

Single-Nanoparticle/Quantum Dot Tracking for Surface Diffusion of AMPAR

For AMPAR-quantum dot (QD) tracking, hippocampal neurons were transfected with GluA1::pHluorin or GluA2::pHluorin, along with Homer1::dsRed, as previously described (Klueva et al., 2014). For the Noelin1 effect on mobility after hyaluronidase treatment, cells were treated with hyaluronidase (250 U) for 1 hr prior to measurement. Noelin1-3 conditioned medium (720 fmol ⋅ μL−1) or control medium was added and incubated for 20 min prior to measurements.

Electrophysiology

All electrophysiological recordings (HEK293T) were made as previously described (Klaassen et al., 2016), with minor modifications. Whole-cell recordings were carried out at room temperature (22°C–24°C). Dissociated hippocampal neurons at DIV18 were visualized by a 63× water immersion objective (Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (bar graphs) or as median and IQR (25%/75%; boxplots). Statistical significances were tested using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software v6.0, USA). The D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test was performed to test for data normality, followed by an F test to compare variances (p value cutoff > 0.05); subsequently, unpaired t tests or unpaired t tests with Welch’s correction were applied. If data were not normally distributed, a Mann-Whitney U test was used. p values and ns are indicated in the figures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following: EU Marie Curie ITN BrainTrain (MEST-ITN-2008-238055 to N.J.P. and C.S. and MEST-ITN-2013-607616 to M.A.G.-L.), HEALTH-2009-2.1.2-1 EU-FP7 “SynSys” (#242167 to A.B.S., H.D.M., and S.S.), and the Dutch Neuro-Bsik Mouse Pharma Phenomics consortium (grant BSIK 03053SenterNovem to A.B.S. and H.D.M.); by an NWO VICI grant (ALW-Vici 016.150.673/865.14.002 to S.S. and ALW-VICI 865.13.002 to H.D.), ERC grant BrainSignals (281443 to H.D.), the DFG (SFB779 B14 to R.F.), and the Swedish Research Council (VR no. D0571301 to U.H.D.). We thank O. Kobler and the special lab for electron and light microscopy a the Leipniz Institute for Neurobiology for help with STED imaging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.J.P., C.S., U.H.D., H.D.M., M.H., K.W.L., S.S., R.F., and A.B.S.; Methodology, N.J.P., C.S., N.B., M.A.G.-L., V.M., J.C.L., and Y.G.; Formal Analysis, N.J.P., C.S., N.B., M.A.G.-L., V.M., J.C.L., U.H.D., K.W.L., M.H., S.S., and R.F.; Investigation, N.J.P., C.S., N.B., V.M., J.C.L., and Y.G.; Writing – Original Draft, N.J.P., S.S., and A.B.S.; Writing – Review & Editing, S.S., F.R., and A.B.S.; Visualization, N.J.P., C.S., and S.S.; Supervision, H.D.M., U.H.D., K.W.L., S.S., R.F., and A.B.S.

Declaration of Interests

A.B.S. participates in a holding that owns shares of Sylics BV. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Published: July 31, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, eight figures, and two tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.102.

Contributor Information

Sabine Spijker, Email: s.spijker@vu.nl.

August B. Smit, Email: guus.smit@vu.nl.

Supplemental Information

References

- Ando K., Nagano T., Nakamura A., Konno D., Yagi H., Sato M. Expression and characterization of disulfide bond use of oligomerized A2-Pancortins: extracellular matrix constituents in the developing brain. Neuroscience. 2005;133:947–957. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barembaum M., Moreno T.A., LaBonne C., Sechrist J., Bronner-Fraser M. Noelin-1 is a secreted glycoprotein involved in generation of the neural crest. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:219–225. doi: 10.1038/35008643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bats C., Groc L., Choquet D. The interaction between Stargazin and PSD-95 regulates AMPA receptor surface trafficking. Neuron. 2007;53:719–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brückner G., Grosche J., Schmidt S., Härtig W., Margolis R.U., Delpech B., Seidenbecher C.I., Czaniera R., Schachner M. Postnatal development of perineuronal nets in wild-type mice and in a mutant deficient in tenascin-R. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;428:616–629. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001225)428:4<616::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cais O., Herguedas B., Krol K., Cull-Candy S.G., Farrant M., Greger I.H. Mapping the interaction sites between AMPA receptors and TARPs reveals a role for the receptor N-terminal domain in channel gating. Cell Rep. 2014;9:728–740. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chetkovich D.M., Petralia R.S., Sweeney N.T., Kawasaki Y., Wenthold R.J., Bredt D.S., Nicoll R.A. Stargazin regulates synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors by two distinct mechanisms. Nature. 2000;408:936–943. doi: 10.1038/35050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Pandya N.J., Koopmans F., Castelo-Székelv V., van der Schors R.C., Smit A.B., Li K.W. Interaction proteomics reveals brain region-specific AMPA receptor complexes. J. Proteome Res. 2014;13:5695–5706. doi: 10.1021/pr500697b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constals A., Penn A.C., Compans B., Toulmé E., Phillipat A., Marais S., Retailleau N., Hafner A.-S., Coussen F., Hosy E., Choquet D. Glutamate-induced AMPA receptor desensitization increases their mobility and modulates short-term plasticity through unbinding from Stargazin. Neuron. 2015;85:787–803. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson P.E., Forss-Petter S., Battenberg E.L., deLecea L., Bloom F.E., Sutcliffe J.G. Four structurally distinct neuron-specific olfactomedin-related glycoproteins produced by differential promoter utilization and alternative mRNA splicing from a single gene. J. Neurosci. Res. 1994;38:468–478. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490380413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Alonso J., Sun Y.J., Granger A.J., Levy J.M., Blankenship S.M., Nicoll R.A. Subunit-specific role for the amino-terminal domain of AMPA receptors in synaptic targeting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:7136–7141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707472114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickendesher T.L., Baldwin K.T., Mironova Y.A., Koriyama Y., Raiker S.J., Askew K.L., Wood A., Geoffroy C.G., Zheng B., Liepmann C.D. NgR1 and NgR3 are receptors for chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. Nat. Neurosci. 2012;15:703–712. doi: 10.1038/nn.3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dityatev A., Schachner M., Sonderegger P. The dual role of the extracellular matrix in synaptic plasticity and homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:735–746. doi: 10.1038/nrn2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischknecht R., Heine M., Perrais D., Seidenbecher C.I., Choquet D., Gundelfinger E.D. Brain extracellular matrix affects AMPA receptor lateral mobility and short-term synaptic plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:897–904. doi: 10.1038/nn.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukaya M., Tsujita M., Yamazaki M., Kushiya E., Abe M., Akashi K., Natsume R., Kano M., Kamiya H., Watanabe M., Sakimura K. Abundant distribution of TARP gamma-8 in synaptic and extrasynaptic surface of hippocampal neurons and its major role in AMPA receptor expression on spines and dendrites. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;24:2177–2190. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Lozano M.A., Klemmer P., Gebuis T., Hassan C., van Nierop P., van Kesteren R.E., Smit A.B., Li K.W. Dynamics of the mouse brain cortical synaptic proteome during postnatal brain development. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:35456. doi: 10.1038/srep35456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happel M.F.K., Frischknecht R. Composition and Function of the Extracellular Matrix in the Human Body. InTech; 2016. Neuronal Plasticity in the Juvenile and Adult Brain Regulated by the Extracellular Matrix. [Google Scholar]

- Heine M. Surface traffic in synaptic membranes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012;970:197–219. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0932-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine M., Thoumine O., Mondin M., Tessier B., Giannone G., Choquet D. Activity-independent and subunit-specific recruitment of functional AMPA receptors at neurexin/neuroligin contacts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:20947–20952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804007106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huganir R.L., Nicoll R.A. AMPARs and synaptic plasticity: the last 25 years. Neuron. 2013;80:704–717. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova D., Dirks A., Montenegro-Venegas C., Schöne C., Altrock W.D., Marini C., Frischknecht R., Schanze D., Zenker M., Gundelfinger E.D., Fejtova A. Synaptic activity controls localization and function of CtBP1 via binding to Bassoon and Piccolo. EMBO J. 2015;34:1056–1077. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaafari N., Henley J.M., Hanley J.G. PICK1 mediates transient synaptic expression of GluA2-lacking AMPA receptors during glycine-induced AMPA receptor trafficking. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:11618–11630. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5068-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen R.V., Stroeder J., Coussen F., Hafner A.-S., Petersen J.D., Renancio C., Schmitz L.J.M., Normand E., Lodder J.C., Rotaru D.C. Shisa6 traps AMPA receptors at postsynaptic sites and prevents their desensitization during synaptic activity. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10682. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klueva J., Gundelfinger E.D., Frischknecht R.R., Heine M. Intracellular Ca2+ and not the extracellular matrix determines surface dynamics of AMPA-type glutamate receptors on aspiny neurons. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014;369:20130605. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraszewski K., Mundigl O., Daniell L., Verderio C., Matteoli M., De Camilli P. Synaptic vesicle dynamics in living cultured hippocampal neurons visualized with CY3-conjugated antibodies directed against the lumenal domain of synaptotagmin. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:4328–4342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04328.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lein E.S., Hawrylycz M.J., Ao N., Ayres M., Bensinger A., Bernard A., Boe A.F., Boguski M.S., Brockway K.S., Byrnes E.J. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445:168–176. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lensjø K.K., Christensen A.C., Tennøe S., Fyhn M., Hafting T. Differential expression and cell-type specificity of perineuronal nets in hippocampus, medial entorhinal cortex, and visual cortex examined in the rat and mouse. eNeuro. 2017;4 doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0379-16.2017. ENEURO.0379-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGillavry H.D., Song Y., Raghavachari S., Blanpied T.A. Nanoscale scaffolding domains within the postsynaptic density concentrate synaptic AMPA receptors. Neuron. 2013;78:615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira A., Vikeved E., Nilsson A., Sjögren B., Andrén P.E., Svenningsson P. Identification of protein-protein interactions by surface plasmon resonance followed by mass spectrometry. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 2011;65 doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps1921s65. 19.21.1–19.21.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno T.A., Bronner-Fraser M. The secreted glycoprotein Noelin-1 promotes neurogenesis in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 2001;240:340–360. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair D., Hosy E., Petersen J.D., Constals A., Giannone G., Choquet D., Sibarita J.-B. Super-resolution imaging reveals that AMPA receptors inside synapses are dynamically organized in nanodomains regulated by PSD95. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:13204–13224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2381-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya N., Sultana A., Lee H.-S., Tomarev S.I. Olfactomedin 1 interacts with the Nogo A receptor complex to regulate axon growth. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:37171–37184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.389916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant K., Pelkey K.A., Bortolotto Z.A., Morita D., Terashima A., McBain C.J., Collingridge G.L., Isaac J.T.R. Transient incorporation of native GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors during hippocampal long-term potentiation. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:602–604. doi: 10.1038/nn1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronker M.F., Bos T.G.A.A., Sharp T.H., Thies-Weesie D.M.E., Janssen B.J.C. Olfactomedin-1 has a V-shaped disulfide-linked tetrameric structure. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:15092–15101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.653485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao-Ruiz P., Carney K.E., Pandya N., van der Loo R.J., Verheijen M.H.G., van Nierop P., Smit A.B., Spijker S. Time-dependent changes in the mouse hippocampal synaptic membrane proteome after contextual fear conditioning. Hippocampus. 2015;25:1250–1261. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riga D., Kramvis I., Koskinen M.K., Van Bokhoven P., van der Harst J.E., Heistek T.S., Jaap Timmerman A., van Nierop P., van der Schors R.C., Pieneman A.W. Hippocampal extracellular matrix alterations contribute to cognitive impairment associated with a chronic depressive-like state in rats. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai8753. eaai8753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz L.J.M., Klaassen R.V., Ruiperez-Alonso M., Zamri A.E., Stroeder J., Rao-Ruiz P., Lodder J.C., van der Loo R.J., Mansvelder H.D., Smit A.B., Spijker S. The AMPA receptor-associated protein Shisa7 regulates hippocampal synaptic function and contextual memory. eLife. 2017;6:e24192. doi: 10.7554/eLife.24192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell E., Sizemore M., Karimzadegan S., Chen L., Bredt D.S., Nicoll R.A. Direct interactions between PSD-95 and stargazin control synaptic AMPA receptor number. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:13902–13907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172511199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk J., Harmel N., Zolles G., Bildl W., Kulik A., Heimrich B., Chisaka O., Jonas P., Schulte U., Fakler B., Klöcker N. Functional proteomics identify cornichon proteins as auxiliary subunits of AMPA receptors. Science. 2009;323:1313–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1167852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk J., Harmel N., Brechet A., Zolles G., Berkefeld H., Müller C.S., Bildl W., Baehrens D., Hüber B., Kulik A. High-resolution proteomics unravel architecture and molecular diversity of native AMPA receptor complexes. Neuron. 2012;74:621–633. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk J., Baehrens D., Haupt A., Bildl W., Boudkkazi S., Roeper J., Fakler B., Schulte U. Regional diversity and developmental dynamics of the AMPA-receptor proteome in the mammalian brain. Neuron. 2014;84:41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger C., Christopeit T., Fuchs K., Grote K., Sieghart W., Danielson U.H. Histaminergic pharmacology of homo-oligomeric β3 γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors characterized by surface plasmon resonance biosensor technology. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012;84:341–351. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeger C., Talibov V.O., Danielson U.H. Biophysical analysis of the dynamics of calmodulin interactions with neurogranin and Ca2+ /calmodulin-dependent kinase II. J. Mol. Recognit. 2017;30:e2621. doi: 10.1002/jmr.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana A., Nakaya N., Dong L., Abu-Asab M., Qian H., Tomarev S.I. Deletion of olfactomedin 2 induces changes in the AMPA receptor complex and impairs visual, olfactory, and motor functions in mice. Exp. Neurol. 2014;261:802–811. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomarev S.I., Nakaya N. Olfactomedin domain-containing proteins: possible mechanisms of action and functions in normal development and pathology. Mol. Neurobiol. 2009;40:122–138. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita S., Fukata M., Nicoll R.A., Bredt D.S. Dynamic interaction of stargazin-like TARPs with cycling AMPA receptors at synapses. Science. 2004;303:1508–1511. doi: 10.1126/science.1090262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twomey E.C., Yelshanskaya M.V., Grassucci R.A., Frank J., Sobolevsky A.I. Elucidation of AMPA receptor-stargazin complexes by cryo-electron microscopy. Science. 2016;353:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zundert G.C.P., Trellet M., Schaarschmidt J., Kurkcuoglu Z., David M., Verlato M., Rosato A., Bonvin A.M.J.J. The DisVis and PowerFit web servers: explorative and integrative modeling of biomolecular complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 2017;429:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Engelhardt J., Mack V., Sprengel R., Kavenstock N., Li K.W., Stern-Bach Y., Smit A.B., Seeburg P.H., Monyer H. CKAMP44: a brain-specific protein attenuating short-term synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus. Science. 2010;327:1518–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.1184178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J.F., Ho H., Greger I.H. Synaptic transmission and plasticity require AMPA receptor anchoring via its N-terminal domain. eLife. 2017;6:e23024. doi: 10.7554/eLife.23024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D., Tomita S. Defined criteria for auxiliary subunits of glutamate receptors. J. Physiol. 2012;590:21–31. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.213868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuzaki M. The C1q complement family of synaptic organizers: not just complementary. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2017;45:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.