Abstract

Background:

Congestive heart failure is an increasingly prevalent terminal illness in a globally aging population. Prognosis for this disease remains poor despite optimal therapy. Evidence suggests that a palliative care approach may be beneficial – and is currently recommended – in advanced congestive heart failure but these services remain underutilized.

Objectives:

To identify the main challenges to the access and delivery of palliative care in patients with advanced congestive heart failure, and to summarize recommendations for clinical practice based on the available literature.

Methods:

MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched for articles published from 1995-2017 pertaining to end of life care in individuals suffering from CHF. Only four randomized controlled trials were found.

Results:

We identified ten key challenges to access and delivery of palliative care services in this patient population: (1) Prognostic uncertainty, (2) Provider education/training, (3) Ambiguity surrounding coordination of care, (4) Timing of palliative care referral, (5) Inadequate community supports, (6) Difficulty communicating uncertainty, (7) Fear of taking away hope, (8) Insufficient advance care planning, (9) Inadequate understanding of illness, and (10) Discrepant patient/family care goals. Provider and patient education, early discussion about prognosis, and a multidisciplinary team-based approach are recommended as we move towards a model where symptom palliation exists concurrently with active disease-modifying therapies.

Conclusion:

Despite evidence that palliative care may improve symptom control and quality of life in patients with advanced congestive heart failure, a multitude of current challenges hinder access to these services. Education, early discussion of prognosis and advance care planning, and multidisciplinary team-based care may be a helpful initial approach as further targeted work addresses these challenges.

Keywords: Heart failure, aging, end-of-life, palliative care, terminal care, quality of life

1. INTRODUCTION

In our globally aging population, an increasing number of people are diagnosed with (and die from) Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) each year. 5.7 million Americans over the age of 20 suffer from CHF, and between 2012 and 2030 this number is projected to increase by 46% [1]. Approximately 50% of patients with CHF will die within 5 years of diagnosis [2, 3], and median survival after the first CHF-related hospitalization is only 2.4 years [4].

CHF is often not acknowledged as a terminal illness until disease is very advanced [5]. Despite optimal medical management of CHF, the reality of a generally poor prognosis is seldom communicated to patients and their families [6].

Symptom management during end-of-life in advanced CHF tends to focus on dyspnea, pain, peripheral edema and fatigue – the cumulative burden of which is equivalent – and in some cases worse – than in patients with cancer [7, 8]. Furthermore, these patients experience inescapable feelings of disability, of being a burden to their friends and family, and have limited community supports [9].

The National Cancer Institute describes palliative care as striving “to improve the quality of life of patients who have a serious or life-threatening disease…with the goal to prevent or treat, as early as possible, the symptoms and side effects of the disease and its treatment, in addition to the related psychological, social, and spiritual problems” [10]. Palliative care is well-recognized in the setting of malignancy but to date has had considerably less presence in non-malignant chronic diseases such as CHF despite research suggesting numerous potential benefits [11].

Despite a growing body of work in recent years describing the various difficulties and challenges in providing palliative care to this unique subpopulation, a dedicated attempt to encapsulate all of these challenges does not exist. Our work seeks to fill this void by way of a narrative review of the heart failure literature with the expressed intent of providing clarity to this topic. It is our hope that this will provide an educational framework for healthcare practitioners and the lay public about the benefits (and limits) of palliative care in CHF.

2. METHODS

We performed a narrative review to broadly survey the general state of evidence regarding end-of-life care for patients with CHF, with the intent of describing current challenges in delivering effective palliative care to these patients. The phrases “palliative care” and “end-of-life care” were used interchangeably in our review for reasons of simplification and article inclusivity. Similarly, both Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF) and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) were collectively referred to as “CHF”. To set boundaries on our search, we excluded articles pertaining to advanced heart failure therapies including home or hospice inotrope/subcutaneous furosemide infusion programs, mechanical circulatory support, implanted cardiac electrical devices for primary prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD), and cardiac transplantation. Given that there is no clear definition of “end-of-life” [12], we defined “end-of-life care” as medical care or psychosocial support received during the time frame in which patients’ disease was felt to be advanced, progressive, and incurable.

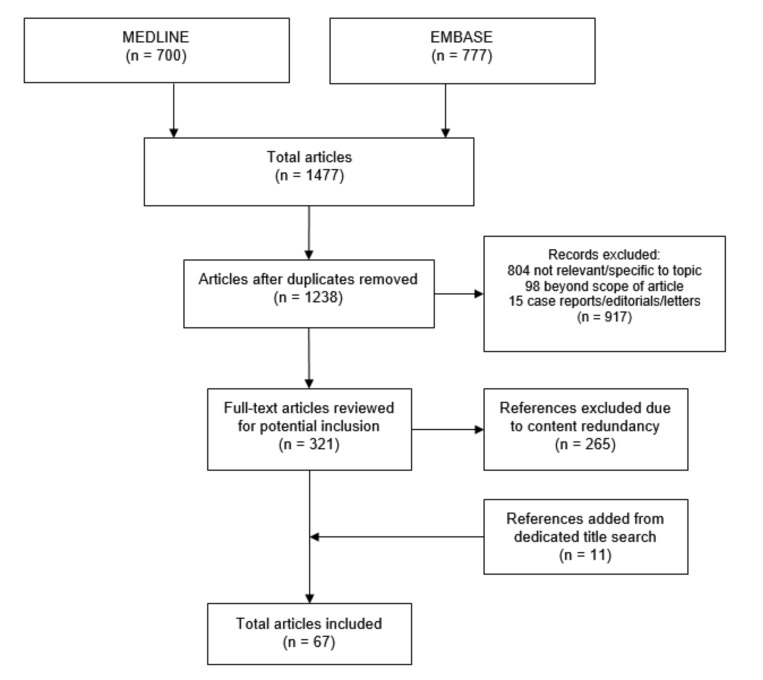

We employed a MEDLINE search strategy using the medical subject heading (MeSH) search terms (“Palliative care” OR “Palliative Medicine” OR “terminal care”) AND “heart failure” and limited our search to articles published from 1995 onwards in humans for which a full text was available. This yielded 700 scholarly articles of various types. A similar EMBASE search with the search terms (“Palliative therapy” OR “Terminal care”) AND “heart failure” yielded 777 articles. Through an article selection process shown in Fig. (1), 67 articles were included in our final review. Only four of these articles were randomized controlled trials.

Fig. (1).

Narrative literature review search strategy.

Recurring themes in the selected articles were identified and summarized in relation to our research question: What are current challenges in delivering palliative/end-of-life care to patients with advanced CHF? Within the limitations of our project’s scope, we corroborated recommendations to address these challenges based on a) the available body of evidence and b) consensus opinions of the authors within our literature review. Due to the paucity of high-quality studies concerning this clinically important topic, we deemed that rigorous critical appraisal and stratification methods to communicate the strength of our findings and recommendations were not applicable to this work.

3. CASE VIGNETTE

Mrs. Y was an 87-year old female who presented to acute care with decompensated biventricular CHF secondary to medication non-compliance and dietary indiscretion in the context of longstanding hypertension and ischemic heart disease. An echocardiogram demonstrated a left ventricular systolic ejection fraction of 15%. Her past medical history was remarkable for dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus and a remote non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Her medications included aspirin, carvedilol, ramipril, nitroglycerin patch, spironolactone, atorvastatin, furosemide, metformin and insulin. For unclear reasons, Mrs. Y was unable to identify who her cardiologist was, nor who was following her from a cardiac perspective. She was promptly admitted to the cardiology ward for medical stabilization with IV diuretics and supportive care.

On admission, Mrs. Y clearly expressed a desire to avoid invasive or heroic measures should her condition deteriorate; she was therefore given a “do not resuscitate” goals of care designation. Five days later, Mrs. Y became acutely hypotensive (systolic blood pressure in the 60’s), hypothermic (temperature 35.3 degrees), delirious, and developed an oliguric acute kidney injury. She was started on systemic antibiotics for suspected sepsis but further workup revealed that she was in cardiogenic shock. The patient’s goals of care were revisited at the bedside with her husband present, who begged her in tears to hold on to life because he “wanted her to live”. Mrs. Y reluctantly agreed, and at her request, her designation was changed to “full code”. She was transferred to the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU) for intubation and advanced vasopressor/inotropic support. Even with these therapies, unfortunately, her clinical condition continued to decline. Repeated emotional discussions between Mrs. Y’s husband and the CICU physicians were held to review the patient’s options for further care, and ultimately a mutual decision was reached to pursue palliation and transition to comfort care. Mrs. Y eventually passed away the next day.

4. THE EMERGING ROLE OF PALLIATIVE CARE IN ADVANCED HEART FAILURE

At this time, the evidence base for palliative care in advanced CHF is sparse; the limited guidelines/consensus statements available are largely guided by expert opinion or extrapolated from studies in patients with cancer. Nonetheless, the need for symptom palliation in advanced CHF is gaining recognition, and current American Heart Association (AHA) heart failure guidelines (2013) recommend early involvement of palliative care teams for symptom management and improving quality of life [13]. The AHA also recently released a policy statement on palliative care in cardiovascular disease and stroke which advocated for early involvement of a palliative care approach to improve quality of life in symptomatic heart failure [14].

There are currently four randomized trials describing the role of palliative care in heart failure. Brännström and Boman (2014) compared usual care to a model of palliative home care (referred to as the “PREFER” model) in a sample of 62 patients with New York Heart Association (NHYA) class III/IV symptoms with follow-up at one, three and six months. Patients in the PREFER model experienced improved health-related quality of life, nausea, total symptom burden and self-efficacy. Most strikingly, they also experienced improved NYHA class symptoms and had fewer re-hospitalizations relative to the control group [15]. In the inpatient setting, Sidebottom et al. (2015) randomized a sample of 232 patients hospitalized with decompensated CHF to receiving a palliative care referral vs. usual inpatient care (which may or may not have included a palliative care referral). Those in the former group had a modest short-term improvement in total symptom burden, quality of life, and depressive symptoms at one and three-month follow-up compared to usual care [16]. Wong et al. (2016) published a phase-three randomized clinical trial of 84 patients with NYHA class III/IV symptoms admitted to hospital with decompensated CHF. In addition to an improvement in CHF symptoms, those who were referred to a multidisciplinary palliative care service at discharge had a 55% reduction in re-admission rate at 12 weeks compared to those who were discharged to usual care [17]. Most recently, Rogers et al. (2017) conducted a single-centre randomized clinical trial (PAL-HF) of 150 patients hospitalized with advanced HF. The authors demonstrated that, compared to usual care, patients who received a palliative care intervention during their hospitalization followed by ongoing management in the outpatient environment reported improvements in quality-of-life at six months after discharge based on validated questionnaires [18].

The developing evidence base suggests that Mrs. Y, the elderly woman from our case vignette, may have derived benefit from a palliative care approach in the final months of her life. Unfortunately, this conversation was not broached until she was in extremis in the CICU. In addition to traditional evidence-based medical therapies for heart failure, medications central to palliative care such as antidepressants and opioids can provide symptom relief [19]. Even digoxin, an old medication that has largely fallen out of favour in the realm of heart failure management, may be useful in managing heart failure symptoms and preventing hospital readmissions, especially in the setting of hypotension when using a palliative care approach [20].

5. CHALLENGES FOR PALLIATIVE CARE IN THE SETTING OF END-STAGE HEART FAILURE

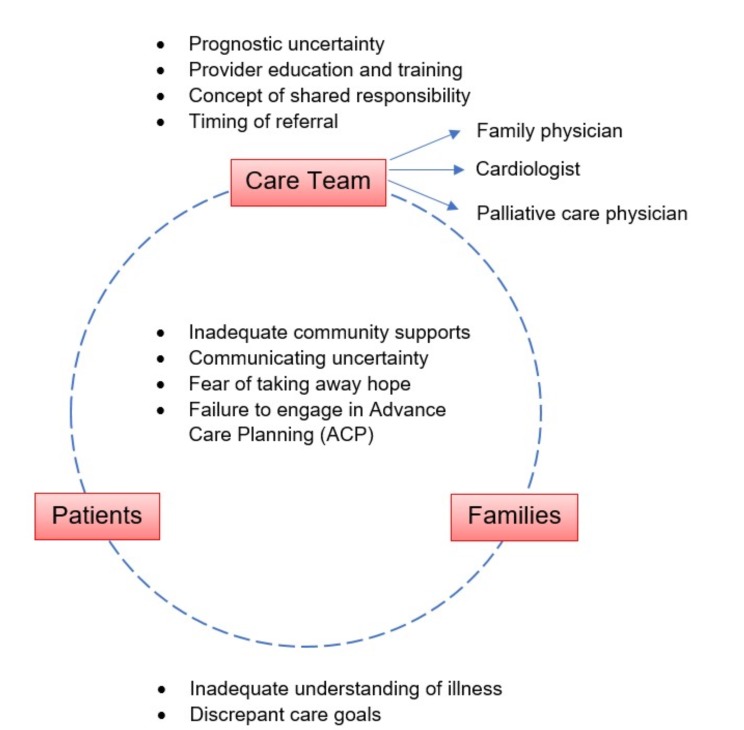

Our review identified ten distinct challenges to delivering effective palliative/end-of-life care in the setting of advanced CHF. These are framed in relation to key stakeholders (care providers, patients, and families) as shown in Fig. (2).

Fig. (2).

Challenges in end-of-life care for patients with advanced congestive heart failure.

5.1. Prognostic Uncertainty

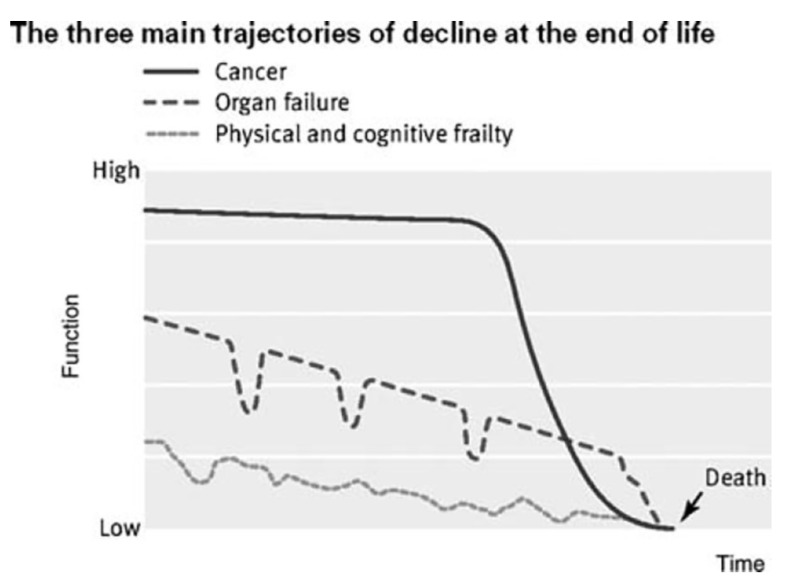

Compared to the well-established mortality curve for cancer, mortality is far more variable in chronic non-malignant conditions like CHF [21], a distinction illustrated in Fig. (3). This is a consequence of the exacerbating-remitting course of the disease. In one study, only 15.7% of surveyed physicians reported that they could confidently predict patients’ clinical trajectories within a 6-month time frame [22], thus making it exceedingly challenging for clinicians to recognize the transition to end-of-life; this phenomenon that has been referred to in the literature as “prognostic paralysis” [23].

Fig. (3).

Typical illness trajectories for people with progressive chronic illness. Reprinted with permission from Jaarsma et al., Eur J Heart Failure 2009. Adapted from Murray et al., BMJ 2005.

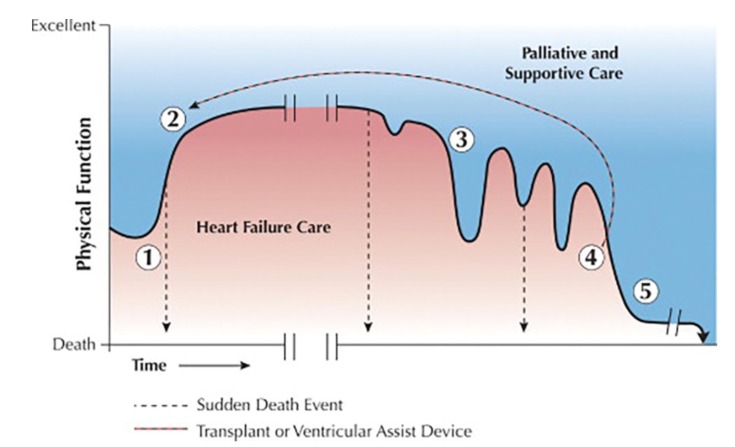

Further properties of advanced CHF make prognostication evermore challenging. SCD from dangerous ventricular arrhythmias or myocardial infarction can occur at any time. Implantable left/bi-ventricular assist devices and Internal Cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) have the potential to substantially alter disease course. The same can be said for cardiac transplantation. These nuances specific to CHF are illustrated in Fig. (4) [24].

Fig. (4).

Schematic depiction of comprehensive heart failure care. Phase 1: development of initial CHF symptoms. Phase 2: Variable plateau duration achieved with initial medical management, or return to medical baseline following advanced mechanical circulatory support (e.g. left/biventricular assist device) or cardiac transplantation. Phase 3: Declining functional status characterized by recurrent CHF exacerbations and/or hospital readmissions. Phase 4: CHF symptoms become refractory to medical management; poor functional status. Phase 5: Predominantly comfort-focused end-of-life care. Reprinted with permission from Goodlin, JACC 2009.

In the setting of advanced CHF, the use of ICDs for primary prevention of SCD raises important ethical considerations. ICD shocks can cause patients significant discomfort, calling into question the benefits of life prolonging measures vs. preserving quality of life [25]. The decision of whether existing ICDs should be deactivated or left on (thereby prolonging the dying process) at the end-of-life presents a unique ethical dilemma beyond the scope of this article, but is a consideration that should be addressed prior to device implantation. This subject is thoughtfully reviewed in detail by Kramer et al. (2012) [26].

NYHA class [27], number of hospitalizations [4] and functional capacity (as determined by VO2 max testing) [28] have been used as clinical indicators to evaluate prognosis in CHF. Biochemical markers such as N-Terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-BNP) have also been shown to correlate with disease severity [29]. However, prognostication of CHF with these methods has been met with limited success [11].

Two validated clinical scoring systems that have been used to prognosticate heart failure are the Seattle Heart Failure Model (SHFM) [30] and the Heart Failure Survival Score (HFSS) [31]. The SHFM is a web-based tool that has been shown to help predict the relative risk of SCD (from arrhythmia) vs. pump failure death among ambulatory CHF patients [32]. It is the most extensively validated prognostic model for end-stage CHF, and thus is considered the current “gold-standard” for prognostication [33]. That being said, the model is cumbersome in that it requires the input of fourteen continuous and ten categorical variables into a complex formula [34]. The HFSS was originally developed as a risk-stratification model for patients with severe CHF (NYHA class III/IV symptoms) to aid in selecting candidates for cardiac transplant. Its main criticism is that its parameters were validated before the use of modern disease-modifying therapies (e.g. widespread beta-blockade, ACE-inhibitor/ angiotensin II (AT1) receptor blocker use, aldosterone antagonists, etc.) so its predictive value may not be as applicable to modern clinical practice [35].

Importantly, none of our current methods for prognostication of CHF are yet satisfactory. Much of this appears to be due to the natural unpredictable course of the disease. While the clinical scoring systems show promise, they are not without their shortcomings. Neither of these models account for co-morbidity, which further reduces their clinical utility [36].

5.2. Provider Education and Training

Healthcare providers often do not recognize that CHF is an incurable, progressive, and terminal disease until it is too late [37]. This recognition is made more difficult from the standpoint of cardiologists because modern treatments and therapies have dramatically altered the clinical course of end-stage CHF over the last twenty years [38].

As described by Kavalieteratos et al. (2014), there is a striking discrepancy among providers between perceived and actual knowledge of what palliative care is and where it fits in the spectrum of managing advanced CHF [5]. When surveyed, most nonpalliative care physicians reported that they could define palliative care but incorrectly identified palliative care as mandating the cessation of life-prolonging therapies [5]. Physicians recognized the importance of initiating conversations about Advanced Care Planning (ACP) and involvement of a palliative care physician but frequently acknowledged not knowing what services were provided or how to access them [5]. It is conceivable that these provider attitudes are a factor in the low referrals to hospice in the last six months of life [39], despite recent data associating hospice enrollment to decreased hospital re-admission rates, use of acute medical care resources and improved symptom control [40].

5.3. Shared Responsibility for Patients with Advanced CHF

Delivery of palliative care as it relates to end-stage heart failure still suffers from disconnectedness – and with it, poor quality and continuity of care [41]. In fact, the term “heart failure care teams” is a misnomer as the phrase falsely implies coherence and stability [42]. Systematic barriers to palliative care discussion and limited ACP discussion make patients with heart failure more likely to die in acute care settings than patients with cancer [43]. Our discussion of Mrs. Y’s case echoes this sentiment. Compared to the relatively smooth and unified relationship that exists between palliative care physicians and oncologists, there is a developmental gap in the relationship between palliative care physicians and cardiologists with clear room for improvement [23].

Part of the disconnect likely arises from the difficulty in assigning responsibility for patient care to a single provider. Because standard medical therapies for CHF play a role in controlling symptoms, they should not be stopped unless they are causing adverse side effects (hypotension, presyncope, acute kidney injury, etc.). Palliative care physicians may feel uncomfortable modifying cardiovascular medications, especially when daily volume assessment and fine tuning of patients’ diuretic regimens is required to maintain euvolemia [44]. Similarly, cardiologists may be uncomfortable adjusting doses of the medications (e.g. opioids, neuroleptics) that are routinely used in palliative care. This brings to attention the need for a shared approach with division of responsibility when caring for patients with advanced/end-stage CHF.

Particularly alarming in Mrs. Y’s case was the fact that it was unclear to both the acute care physicians and patient just who the primary clinician responsible for her care was. In the context of her advanced age, it remains plausible that Mrs. Y had underlying cognitive impairment, although she had no such prior diagnosis and cognition was never formally evaluated prior to her death. Even in the context of a shared model of care, one of the fundamental questions is who is best suited to co-ordinate care for patients with heart failure at the end of life, whether it is a specialist, CHF nurse as part of a multidisciplinary CHF care team – or the patient’s general practitioner. There remains considerable debate about this topic [45, 46].

5.4. When is it Time to Refer to a Palliative Care Physician?

There is a pervasive misconception in clinical medicine that palliative care becomes appropriate only when attempts at cure of a terminal illness or disease state have been unsuccessful. Even in the realm of CHF, palliative care is associated almost exclusively with pre-death care [47]. When interviewed, cardiologists often stated that they saw palliative care involvement as the point at which they could do no more [5], while some providers even suggested that palliative care be withheld until the patient is clearly dying [42]. In retrospect, it is plausible that this mindset was a factor in Mrs. Y’s clinical outcome.

In the heart failure literature, several attempts at standardizing the palliative care referral process have been made to reduce the ambiguity concerning this matter. O’Leary et al. (2009) identified a “palliative transition point” at which the focus of care in the patient with CHF should shift towards addressing symptom control and comfort rather than disease-modifying or curative efforts [48]. Similarly, Jaarsma et al. (2009) put forward a list of “triggers” for initiating a palliative discussion with patients and their families [36]. Both models are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Models for timing of palliative care consultation.

| Triggers-based Modela | Using a Palliative “Transition Point”b |

|---|---|

| Deterioration despite maximum optimal multidisciplinary support Increasing fatigue and/or functional dependence Low left ventricular ejection fraction Recurrent hospitalizations Emotional distress Caregiver fatigue At the patient’s request |

Recurrent decompensations within 6 months despite optimal therapy Malignant arrhythmias (ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation) Need for frequent courses of continuous IV therapy Chronic poor quality of life Intractable NYHA class IV symptoms Cardiac cachexia |

aAdapted from O’Leary N, Murphy NF, O’Loughlin C, Tiernan E, McDonald K. Eur J Heart Failure 2009; 11: 406-12.

bAdapted from Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder et al. Eur J Heart Failure 2009; 11: 433-43.

Considering the daunting task of assessing a patient’s “suitability” for palliative care referral, some experts argue that this complex decision-making process should be avoided altogether, further suggesting a palliative-focused discussion right from the initial heart failure diagnosis [6, 11, 34]. Hupcey et al. (2009) further develop this idea, advocating for a gradual shift in the clinical presence of palliative care as the CHF trajectory progresses and symptoms become more and more refractory to traditional medical management. Importantly, the authors stress that some level of active medical treatment continues throughout the entire trajectory of care due to the cross-over effect that disease-modifying therapies have in controlling symptoms [49].

5.5. Shared Challenges in Delivering Effective Palliative/End-of-life Care in Advanced CHF

We found the literature rife with examples of challenges involving all stakeholders in this discussion. Most frequently cited were inadequate community supports, deficits in communication (with respect to communicating prognostic uncertainty vs. the fear of taking away hope) and failure to discuss ACP.

It is not surprising that, given the relatively underdeveloped role of end-of-life/palliative care in non-malignant chronic diseases as opposed to cancer, the end-of-life needs for patients with advanced CHF are woefully under-recognized and under-addressed in the community. In one study out of Ontario, Canada, patients with advanced CHF were less likely to be identified as end-stage requiring palliative care despite greater levels of functional impairment and caregiver burnout [8]. Further to this sentiment is the observation that patients with CHF are often ineligible for certain community services (e.g. subsidized equipment, support groups, and transportation programs) which are normally afforded to those receiving palliative care support for cancer [50]. From a community standpoint, this leaves a significant population subgroup underserved.

The AHA recommends revisiting prognosis on an annual basis at a yearly “heart failure review” [14], although in practice this is seldom done. One study reported as few as 12% of physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician’s assistants discussed prognosis annually with their heart failure patients, with 4% never discussing prognosis at all [46]. Consequently, palliative care referrals for patients with advanced CHF remain the exception rather than the norm [48]. Reasons for this are multifactorial but likely stem from misconceptions about the role of palliative care in chronic non-malignant terminal disease.

The intricacies surrounding communication regarding prognosis, preferences and ACP in heart failure are complex, but at this stage still possess many gaps. As previously described, a significant component underlying providers’ reluctance to have “the conversation” is prognostic uncertainty [37, 38]. Further to this, for clinicians who are traditionally focused on curative and disease-modifying interventions to improve quantity of life, there exists to some degree the notion that “palliative care” implies treatment failure – and extending this line of thinking – failure of the clinician [6, 45]. Especially in the realm of heart failure management with its rapid advances in medical care, there seems to always be “one more thing to try”, which makes shifting the focus of care from life extension to symptom relief difficult to accept [38, 51]. As was previously discussed, providers generally have limited knowledge with regards to what palliative care is, how to access it, and how it can complement traditional heart failure management – leaving a strong role for provider education in the end-of-life care of these patients [5].

For patients and their families, initiating a palliative care discussion has been likened to the “beginning of the end” and is thought by some to take away patients’ hope [52, 53]. In our earlier case vignette, Mrs. Y’s husband begged her to not “give up” because he wanted her to live. Interestingly, however, at least one study has found that engaging patients in end-of-life discussions led to less aggressive intervention (a decision made by the patient), improved quality of life, and improved post-mortem adjustment for families [54]. It is plausible that if the graveness and severity of Mrs. Y’s illness had been recognized and communicated with the family earlier in her admission, Mr. and Mrs. Y may have been more prepared for comfort-focused care and less aggressive intervention including admission to the CICU.

In light of the overall poor prognosis of advanced CHF, it is of particular concern that advance directives/ACP are seldom discussed. Less than half of patients with advanced CHF have documented advanced directives/goals of care, whether in the community [55] or in hospital [56]. Like in our case, conversations about these issues frequently occur in emergent circumstances [57] and barriers including time [58], not knowing what to discuss, and general discomfort with initiating this discussion [59] are often cited as reasons for putting off this conversation.

5.6. Where do Patients and their Families Fit in?

A final barrier to delivering and receiving effective palliative care services revolves around the sharing of knowledge. Too often, patients and their families are not on the same page as their physicians – and moreover – not on the same page with each other. Many patients have little understanding of CHF as a terminal, progressive and irreversible condition and – not uncommonly – attribute their declining functional status to old age [60, 61]. As Caldwell et al. (2007) describe in detail, the sharing of knowledge regarding the clinical course of CHF is complex, for which the communication of truths and uncertainties must be balanced with hope [53]. Research also indicates that between patients and family caregivers, there exists a certain level of disagreement about symptom severity and satisfaction with medical care, with caregivers tending towards the perception that their loved ones’ condition is more severe and that their medical care is more unsatisfactory [62]. Recent qualitative data shows that while most caregivers do not understand the severity of patients’ CHF symptoms, or that they are dying – in caregivers who did, patients had a higher likelihood of receiving palliative care services [63]. With special attention to shared discussion around topics that are traditionally avoided it is conceivable that this barrier – as it pertains to patients and their families – to the provision of palliative care services can be removed.

6. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PALLIATIVE CARE IN ADVANCED HEART FAILURE

Within the current literature, the authors make several recommendations to expedite and improve access to palliative care services for patients with CHF. Bearing in mind that the vast majority of these recommendations are based on the viewpoints of expert consensus statements rather than clinical trial data, we have summarized the recommendations as a practical check-list in Table 2:

Table 2.

Practical palliative-care model in Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) checklist.

|

At time of diagnosis |

☑ Educate patient and primary caregiver that CHF is a terminal disease. ☑ Discuss advanced care planning with patient and primary caregiver. ☑ Offer referral to a palliative physician. ☑ Offer other allied health referrals for psychosocial support. |

| Throughout continuum of CHF care | ☑ Evidence-based therapies (pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic) for CHF. ☑ Referral to a specialized multidisciplinary heart failure clinic/team for outpatient CHF care. ☑ Address stigma and misconceptions associated with terminal chronic disease and end-of-life through education. ☑ Ongoing re-assessment of a) transitioning goals of care to focus on comfort and b) referral to a palliative care physician if this has not already been done. |

| Transition to comfort and end-of-life care | ☑ Care is predominantly taken over by palliative care physician. ☑ Continued use of evidence-based therapies for CHF. ☑ Addition of other pharmacologic treatments as needed for symptom control: opioids, furosemide, digoxin, antidepressants. ☑ Ongoing multidisciplinary psychosocial support for patient and caregiver. |

6.1. Education for Patients, Families and Healthcare Providers

In one study, caregivers were more receptive to talking about and engaging with palliative care teams once education was offered [47]. There is an urgent need to abolish current misunderstandings of what palliative care is and is not. Comprehensive palliative care services have the potential to help patients and caregivers at any stage of their illness, and thus are appropriate at any time. The case of palliative care in heart failure is no different in this regard and is an issue that is amenable to improvement through thoughtful discussion and education.

6.2. Early Advance Care Planning

Mr. and Mrs. Y’s limited insight into the nature, severity, and prognostic course of her illness may appear surprising, but unfortunately this is a collective experience that is shared by many individuals who suffer from heart failure [36]. Conversations around these topics are rarely initiated by clinicians, and one can only surmise that this was no different for Mrs. Y [64, 65]. Rather than relying on triggers or waiting for abrupt changes in clinical status, we recommend an up-front goals of care discussion, where possible, with the patient and their family at the time of heart failure diagnosis. It is important to be frank about prognostic uncertainty. Hauptman and Havranek (2005) propose an algorithm to integrate palliative care into systolic heart failure management where this discussion occurs very early in the disease course [51]. Lemond (2011) specifically recommends having this discussion and addressing prognostic uncertainty prior to initiating the goals-of-care discussion [34]. Regardless of the strategy employed, early discussion around these issues will help to avoid miscommunication later in the patient’s disease course.

6.3. Using a Patient-centred, Multidisciplinary Team-based Approach

The literature suggests using a team-based approach for palliative care in patients with CHF. One collaborative team-based model for palliative care in heart failure patients enabled 50% of patients to be able to die at home, with only 8.3% of all patients requiring a formal consultation by a palliative physician [66]. As for characterizing the involvement of palliative care in the final years of a terminal illness, various models have been posited depicting the balance between curative and palliative modalities at the end of life. In recent years, we have moved away from a strictly dichotomous model of “curative” vs. “palliative” care towards one of graded palliative care involvement, with a gradual shift in focus from curative to palliative efforts as a disease progresses [67]. This is the model currently employed in the setting of cancer. In CHF, expert consensus recommends a variation of this palliative care model where both disease-modifying/curative and palliative modalities occur simultaneously, like the model described by Lanken et al. (2008) in the setting of incurable respiratory disease [67]. Given the unpredictable disease course of CHF, palliative care services should have a similarly variable trajectory that waxes and wanes with a patient’s functional status, with disease-modifying therapies continuing throughout the spectrum of the patient’s illness – for reasons of both prognostic uncertainty as well as symptom relief [49, 67].

CONCLUSION

Heart failure is a terminal illness that affects a significant proportion of the population in developed countries, and this number continues to increase. In this review article, we have broadly surveyed the literature with regards to end-of-life care in patients with advanced congestive heart failure; we have identified the most pressing issues at present for patient care and have proposed measures to facilitate improved delivery of and access to care in this underserved population. Indeed, our findings may not be considered novel and may significantly overlap with existing published literature. With that said, to the best of our knowledge this is the first large-scale review of the main challenges associated with the effective delivery and co-ordination of palliative/end-of-life care in those dying from advanced CHF. In turn, this serves as a starting point for detailed analysis and development of interventions that affect positive change.

Our work is not without limitations. Due to the paucity of high-quality evidence available (in stark contrast to the large amount of expert opinion found in the literature), we opted to perform a narrative review. Although we have adopted some elements of the systematic method, we have intentionally not placed focus on critical appraisal and recognize that this subjects our work to bias. Using the phrases “end-of-life care” and “palliative care” as well as addressing HFrEF and HFpEF in the same context may be an oversimplification that does not easily lend itself to examining key differences, if they exist, between these conditions with respect to palliative/end-of-life care. Lastly, the recommendations made at the end of our article are predominantly based on expert opinion (some of which may have competing opinions) rather than data, and thus must be interpreted within this context.

Palliative care has a role in managing heart failure symptoms, addressing spiritual and emotional needs, as well as assisting with caregiver burnout. It is not just about care of the dying or care that is provided when curative efforts have been exhausted, and based on current recommendations and an ever-evolving evidence base, should be involved early in the course of heart failure. In our earlier case vignette, the confusion that led to an unnecessary CICU admission in Mrs. Y’s final days could have been avoided if more attention had been invested earlier to eliminate any ambiguity about the severity of her disease, and rather, to acknowledge the reality that Mrs. Y was approaching the end of life. This would have enabled Mrs. Y’s passing to be peaceful, more dignified, and much easier for all affected parties.

Addressing barriers to accessing palliative care services for patients with heart failure is a complex discussion. Education is certainly part of this discussion; there is a definite need to inform families and address pre-existing notions about what palliative care is and is not. Deciding when to involve palliative care services is also a challenge as the disease course and prognosis of heart failure is highly variable. Nonetheless, there is resounding agreement that providers should make it clear to patients and families that heart failure is a terminal diagnosis. Dying comfortably can be one of the most fulfilling contributions one can make to enrich the lives of patients and their families. When discussing goals of care and ACP in CHF, we must abandon the false dichotomy of curative vs. palliative care as the two approaches necessarily exist simultaneously.

FUTURE RESEARCH AND NEXT STEPS

Although clinical trial data in end-of-life care in CHF is just beginning to materialize, translating this work to clinical practice will take time. Further research should look at how to co-ordinate multidisciplinary care teams for patients with advanced heart failure. More broadly, future large-scale studies may involve multi-center trials and longer periods of follow-up, with assessments for impact on mortality, quality of life, caregiver burden, and overall satisfaction with different models of integrated palliative care in inpatient and outpatient settings.

AUTHORSHIP

Justin Chow is the primary author of the manuscript. Helen Senderovich is the senior author and supervisor of this review. Both authors have consented to the submission of this manuscript for consideration of publication.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mozaffarian D., Benjamin E.J., Go A.S., et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2015 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;131:e29–e322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy D., Kenchaiah S., Larson M.G., et al. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;347:1397–1402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger V.L., Weston S.A., Redfield M.M., et al. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. JAMA. 2004;292:344–350. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Setoguchi S., Stevenson L.W., Schneeweiss S. Repeated hospitalizations predict mortality in the community population with heart failure. Am. Heart J. 2007;154:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kavalieteratos D., Mitchell E.M., Carey T.S., et al. “Not the ‘grim reaper service’”: An assessment of provider knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding palliative care referral barriers in heart failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000544. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward C. The need for palliative care in the management of heart failure. Heart. 2002;87:294–298. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.3.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekelman D.B., Rumsfeld J.S., Havranek E.P., et al. Symptom burden, depression, and spiritual well-being: A comparison of heart failure and advanced cancer patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009;24:592–598. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0931-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandes S., Guthrie D.M. A comparison between end-of-life home care clients with cancer and heart failure in Ontario. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2015;34:14–29. doi: 10.1080/01621424.2014.995257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horne G., Payne S. Removing the boundaries: Palliative care for patients with heart failure. Palliat. Med. 2004;18:291–296. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm893oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Cancer Institute Palliative care in cancer. 2010 http://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/advanced-cancer/care-choices/palliative-care-fact-sheet#q1

- 11.Shah A.B., Morrissey R.P., Baraghoush A., et al. Failing the failing heart: A review of palliative care in heart failure. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2013;14:41–48. doi: 10.3909/ricm0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lunney J.R., Lynn J., Foley D.J., et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2387–2392. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yancy C.W., Jessup M., Bozkurt B., et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;62:e147–e239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun L.T., Grady K.L., Kutner J.S., et al. Palliative care and cardiovascular disease and stroke: A policy statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e198–e225. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brännström M., Boman K. Effects of person-centred and integrated chronic heart failure and palliative home care. PREFER: A randomized controlled study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2014;16:1142–1151. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sidebottom A.C., Jorgenson A., Richards H., Kirven J., Sillah A. Inpatient palliative care for patients with acute heart failure: Outcomes from a randomized trial. J. Palliat. Med. 2015;18:134–142. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong F.K.Y., Ng A.Y.M., Lee P.H., et al. Effects of a transitional palliative care model on patients with end-stage heart failure: A randomised controlled trial. Heart. 2016;102(14):1100–1108. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers J.G., Patel C.B., Mentz R.J., et al. Palliative care in heart failure: The PAL-HF randomized, controlled clinical trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017;70(3):332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whellan D.J., Goodlin S.J., Dickinson M.G., et al. End-of-life care in patients with heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 2014;20:121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ambrosy A.P., Butler J., Ahmed A., et al. The use of digoxin in patients with worsening chronic heart failure: Reconsidering an old drug to reduce hospital admissions. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:1823–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray S.A., Kendall M., Boyd K., Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ. 2005;330:1007–1011. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hauptman P.J., Swindle J., Hussain Z., Biener L., Burroughs T.E. Physician attitudes toward end-stage heart failure: A national survey. Am. J. Med. 2008;121(2):127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson M.J., Gadoud A. Palliative care for people with chronic heart failure: When is it time? J. Palliat. Care. 2011;27:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodlin S.J. Palliative care in congestive heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54:386–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss A.J., Zareba W., Hall W.J., et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kramer D.B., Mitchell S.L., Brock D.W. Deactivation of pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012;55:290–299. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed A., Aronow W.S., Fleg J.L. Higher New York heart association classes and increased mortality and hospitalization in heart failure patients with preserved left ventricular function. Am. Heart J. 2006;151:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myers J., Gullestad L., Vagelos R., et al. Clinical, hemodynamic, and cardiopulmonary exercise test determinants of survival in patients referred for evaluation of heart failure. Ann. Intern. Med. 1998;129:286–293. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-4-199808150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Januzzi J.L., Jr Natriuretic peptides, ejection fraction, and prognosis: Parsing the phenotypes of heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013;61:1507–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levy W.C., Mozaffarian D., Linker D.T., et al. The Seattle Heart Failure Model: prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;13:1424–1433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aaronson K.D., Schwartz J.S., Chen T.M., Wong K.L., Goin J.E., Mancini D.M. Development and prospective validation of a clinical index to predict survival in ambulatory patients referred for cardiac transplant evaluation. Circulation. 1997;95:2660–2667. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.12.2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mozaffarian D., Anker S.D., Anand I., et al. Prediction of mode of death in heart failure: The Seattle heart failure model. Circulation. 2007;116:392–398. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.687103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buggey J., Mentz R.J., Galanos A.N. End-of-life heart failure care in the United States. Heart Fail. Clin. 2015;11:615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2015.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lemond L., Allen L.A. Palliative care and hospice in advanced heart failure. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011;54:168–178. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner R.S., McDonagh T.A., MacDonald M., Dargie H.J., Murday A.J., Petrie M.C. Who needs a heart transplant? Eur. Heart J. 2006;27:770–772. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaarsma T., Beattie J.M., Ryder M., et al. Palliative care in heart failure: A position statement from the palliative care workshop of the heart failure association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2009;11:433–443. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glogowska M., Simmonds R., McLachlan S., et al. “Sometimes we can’t fix things”: A qualitative study of health care professionals’ perceptions of end of life care for patients with heart failure. BMC Palliat. Care. 2016;15(3):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0074-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ziehm J., Farin E., Seibel K., Becker G., Köberich S. Health care professionals’ attitudes regarding palliative care for patients with chronic heart failure: An interview study. BMC Palliat. Care. 2016;15(76):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kheirbek R.E., Fletcher R.D., Bakitas M.A., et al. Discharge hospice referral and lower 30-day all-cause readmission in medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:733–740. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yim C.K., Barrón Y., Moore S., et al. Hospice enrollment in patients with advanced heart failure decreases acute medical service utilization. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10:1–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart S., McMurray J.J.V. Palliative care for heart failure: Time to move beyond treating and curing to improving the end of life. BMJ. 2002;325:915–916. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lingard L.A., McDougall A., Schulz V., et al. Understanding palliative care on the heart failure care team: an innovative research methodology. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:901–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Setoguchi S., Glynn R.J., Stedman M., Flavell C.M., Levin R., Stevenson L.W. Hospice, opiates, and acute care service use among the elderly before death from heart failure or cancer. Am. Heart J. 2010;160:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sobanski P., Krajnik M., Beattie J.M. Integrating the complementary skills of palliative care and cardiology to develop care models supporting the needs of those with advanced heart failure. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care. 2016;10:8–10. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanratty B., Hibbert D., Mair F., et al. Doctors’ perceptions of palliative care for heart failure: Focus group study. BMJ. 2002;325:581–585. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7364.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dunlay S.M., Foxen J.L., Cole T., et al. A survey of clinician attitudes and self-reported practices regarding end-of-life care in heart failure. Palliat. Med. 2015;29(3):260–267. doi: 10.1177/0269216314556565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hupcey J.E., Penrod J., Fogg J. Heart failure and palliative care: implications in practice. J. Palliat. Med. 2009;12:531–536. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Leary N., Murphy N.F., O’Loughlin C., Tiernan E., McDonald K. A comparative study of the palliative care needs of heart failure and cancer patients. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2009;11:406–412. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hupcey J.E., Penrod J., Fenstermacher K. A model of palliative care for heart failure. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 2009;26:399–404. doi: 10.1177/1049909109333935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaasalainen S., Strachan P.H., Brazil K., et al. Managing palliative care for adults with advanced heart failure. CJNR. 2011;43(3):38–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hauptman P.J., Havranek E.P. Integrating palliative care into heart failure care. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005;165:374–378. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strand J.J., Kamdar M.M., Carey E.C. Top 10 things palliative care clinicians wished everyone knew about palliative care. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013;88:859–865. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Caldwell P.H., Arthur H.M., Demers C. Preferences of patients with heart failure for prognosis communication. Can. J. Cardiol. 2007;23(10):791–796. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70829-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wright A.A., Zhang B., Ray A., et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dunlay S.M., Swetz K.M., Mueller P.S., Roger V.L. Advance directives in community patients with heart failure. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2012;5:283–289. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Butler J., Binney Z., Kalogeropoulous A., et al. Advance directives among hospitalized patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2015;3(2):112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boyd K.J., Murray S.A., Kendall M., Worth A., Benton T.F., Clausen H. Living with advanced heart failure: A prospective, community based study of patients and their carers. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2001;6(5):585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tung E.E., North F. Advance care planning in the primary care setting: a comparison of attending staff and resident barriers. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 2009;26:456–463. doi: 10.1177/1049909109341871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harding R., Selman L., Beynon T., et al. Meeting the communication and information needs of chronic heart failure patients. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(2):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barclay S., Momen N., Case-Upton S., Kuhn I., Smith E. End-of-life care conversations with heart failure patients: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2011;61(582):e49–e62. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X549018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klindtworth K., Oster P., Hager K., Krause O., Bleidorn J., Schneider N. Living with and dying from advanced heart failure: Understanding the needs of older patients at the end of life. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0124-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Janssen D.J.A., Spruit M.A., Wouters E.F.M., Schols J.M.G.A. Symptom distress in advanced chronic organ failure: Disagreement among patients and family caregivers. J. Palliat. Med. 2012;15(4):447–456. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alonso W., Hupcey J.E., Kitko L. Caregivers’ perceptions of illness severity and end of life service utilization in advanced heart failure. Heart Lung. 2017;46:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rogers A.E., Addington-Hall J.M., Abery A.J., et al. Knowledge and communication difficulties for patients with chronic heart failure: Qualitative study. BMJ. 2000;321:605–607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7261.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fried T.R., Bradley E.H., O’Leary J. Prognosis communication in serious illness: Perceptions of older patients, caregivers, and clinicians. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003;51:1398–1403. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davidson P.M., Paull G., Introna K., et al. Integrated, collaborative palliative care in heart failure: The St. George heart failure service experience 1999-2002. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2004;19:68–75. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200401000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lanken P.N., Terry P.B., Delisser H.M., et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: Palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008;177:912–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]