Abstract

Background:

Patient empowerment, defined as ‘a process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health’ (World Health Organization) is a key theme within global health and social care strategies. The benefits of incorporating empowerment strategies in care are well documented, but little is known about their application or impact for patients with advanced, life-limiting illness(s).

Aim:

To identify and synthesise the international evidence on patient empowerment for adults with advanced, life-limiting illness(s).

Design:

Systematic review (PROSPERO no. 46113) with critical interpretive synthesis methodology.

Data sources:

Five databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CINHAL, PsycINFO and Cochrane) were searched from inception to March 2018. Grey literature and reference list/citation searches of included papers were undertaken. Inclusion criteria: empirical research involving patients with advanced life-limiting illness including descriptions of, or references to, patient empowerment within the study results.

Results:

In all, 13 papers met inclusion criteria. Two qualitative studies explored patient empowerment as a study objective. Six papers evaluated interventions, referencing patient empowerment as an incidental outcome. The following themes were identified from the interpretive synthesis: self-identity, personalised knowledge in theory and practice, negotiating personal and healthcare relationships, acknowledgement of terminal illness, and navigating continued losses.

Conclusion:

There are features of empowerment, for patients with advanced life-limiting illness distinct to those of other patient groups. Greater efforts should be made to progress the empowerment of patients nearing the end of their lives. We propose that the identified themes may provide a useful starting point to guide the assessment of existing or planned services and inform future research.

Keywords: Patient participation, terminal care, power (psychology), health behaviour, palliative care, self-care, review

What is already known about the topic?

Healthcare systems globally are faced with the challenge of how best to support growing older populations with complex medical and social needs.

Models of care incorporating patient empowerment strategies are being increasingly adopted in response to these population changes with the aim of alleviating the impact of morbidity on people’s lives and reducing the demands placed on health and social care services.

Little is known about the application or impact of empowerment strategies for patients with advanced, life-limiting illness(s).

What this paper adds?

To our knowledge, this is the first review to explore the concept of patient empowerment for adults living with advanced, life-limiting illness.

There are features of empowerment, for patients with advanced life-limiting illness, distinct to those of other patient groups. Key differences relate to the continued physical and psychosocial challenges this group encounter, producing contrasting patient empowerment foci.

Our review found no evidence of attempts to incorporate patient empowerment into the design or evaluation of services that support people with advanced life-limiting illness.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

We would propose that the identified themes and conceptual model produced in review may provide a useful starting point to guide the assessment of existing services and development of a new dialogue surrounding patient participation in the design of services and interventions.

Background

The impact of the continuing rise in global average life expectancy is already apparent in many countries with growing older populations with complex medical and social needs.1–3 The concept of ‘patient empowerment’ has gained traction in recent years, responding to these population challenges with the aim of alleviating the impact of morbidity on people’s lives and limiting the demands high levels of morbidity place on health and social care services.4

There are various definitions and applications of patient empowerment (termed ‘patient activation’, in some texts) used within healthcare, with the largest body of research in long-term conditions. Here, the empowerment paradigm involves patients reclaiming their responsibilities to improve and maintain their health, in parallel with a reformation of the patient–doctor relationship4–6 that encourages equitable partnerships over an authoritative dynamic.7 Self-management and self-efficacy are key features within the majority of patient empowerment constructs, with a growing number of measures used in practice to assess, monitor and promote these qualities.5,8,9 There is increasing evidence that patient empowerment is effective and beneficial. Helping patients to achieve improved health states reduces the impact on services and engenders continued participation and motivation from healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients.10,11 Consequently, patient empowerment has gained the attention of policy makers on a global scale, with mandates for, and investment into, initiatives and service structures to empower patients now commonplace.12–15

Existing empowerment tools and models assume a degree of reversibility to patients’ health states and/or the potential to inhibit the progression of a negative health state by means of improved self-care, lifestyle choices and relations with HCPs and services.5,8,11,16 From the perspective of advanced illness, when there is not the potential for health gains, or when disability impedes function and capacity to self-manage and forces dependency on others, these tools and models may cease to be appropriate. This results in this population being inappropriately assessed and subsequently underserved.

This review intends to appraise the international evidence surrounding definitions and/or concepts pertaining to patient empowerment for persons living with advanced, life-limiting disease, with the aim of understanding whether patients can still be ‘empowered’ in the context of advanced, terminal illness and/or whether these patients fall outside of the measures, models and services designed around the current understanding and constructs of ‘patient empowerment’.

Research questions

How has empirical research defined ‘patient empowerment’ for adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness.

What factors/themes are associated with patient empowerment for adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness.

Which interventions or exposures seek to support or promote patient empowerment for adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness.

Methods

Design

We followed systematic review best practices to formulate a search strategy underpinned by study objectives and inclusion criteria, as specified in our registered protocol.17 Which is combined with critical interpretive synthesis18 methodology to integrate data across studies.

Critical interpretive synthesis methodology, developed by Dixon-Woods et al.,18 is an iterative approach designed to appraise and synthesise complex and heterogeneous quantitative and qualitative evidence, in a bid to develop a novel definition, concept or theory. We specifically selected this method for its ability to inform the review question, identification and selection of evidence, as well as synthesis of evidence. The orientation of critical interpretive synthesis towards theory generation makes its practice distinct from that of meta-ethnography and other qualitative synthesis methods.

We adopted this methodology based on the findings of our initial scoping of the literature, which aimed to identify empirical research on empowerment for adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness This exercise identified a small body of literature of methodological heterogeneity, highlighting the challenges of attempting to collate and synthesise evidence where the phenomenon of interest is not well specified and where evidence is very heterogeneous in both type and purpose. These findings, and our aim to contrast our results with existing evidence on empowerment for other patient groups and to build conceptual understanding, informed our decision to conduct a critical interpretive synthesis, rather than use traditional aggregative review methodology. This enabled insights into the concepts underpinning empowerment to emerge through an iterative, dynamic and critical synthesis of the literature.

Search strategy

Search terms (Appendix 1) were generated from the existing research and theoretical literature surrounding patient empowerment and activation.4,6,16,19,20 We subsequently trialled various combinations of concept headings and search terms before settling on a broad search strategy, accepting that we would obtain a large volume of papers of high specificity and low sensitivity.

Screening papers for inclusion was performed by D.W., with queries pertaining to inclusion discussed with F.E.M.M.

Data sources

The following databases were searched from inception to week 2 March 2018: MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO and The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. We also searched Grey literature (Open Grey Database), reference lists of included papers and relevant systematic reviews identified during screening. Pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied during screening.

Inclusion criteria

Empirical research included descriptions of, or references to, patient empowerment within their results, irrespective of whether empowerment featured in the objectives of the study. Included studies report solely on adult patients (>18 years of age) with end-stage, advanced, terminal and/or life-limiting illness and/or who were defined as receiving non-curative management or palliative care support. We utilised the master search strategy developed by Sladek et al.20 to support the capture of literature relevant to palliative care in general medical journals.

We included studies incorporating a mix of participants, including informal carers and HCPs, only in circumstances where patient reported data could be separated and extracted. In recognition of variations in service provision and healthcare constructs internationally,21,22 we selected to focus on features of empowerment specific to patients.

For the purposes of the interpretative review, we retained and kept separately papers, identified during screening, that were clearly concerned with aspects of patient empowerment but included participants with a mixture of both advanced life-limiting disease and a range of other disease states/stages. These papers were later used to compare empowerment themes between the other disease groups and patients with advanced life-limiting disease to support the dialectic processes of the interpretive review.

Exclusion criteria

To capture generalisable features of empowerment in this patient group, we excluded studies with single decision-specific foci, for example, decisions to withdraw dialysis and advance care planning for single-disease groups. Conference abstracts and non-empirical papers were also excluded. There were no language limitations.

We excluded fatally flawed papers identified using the quality appraisal criteria (as cited by Dixon-Woods et al.18):

Are the aims and objectives of the research clearly stated?

Is the research design clearly specified and appropriate for the aims and objectives?

Do researchers provide a clear account of the process by which their findings were produced?

Do the researchers display enough data to support their interpretations and conclusions?

Is the method of analysis appropriate and adequately explicated?

Each potentially included paper was scrutinised, using these criteria, and discussed by at least two of the authors (D.W., J.B. and F.E.M.M.) before deciding on inclusion or exclusion.

Synthesis

First, we considered the context and potential influences and assumptions that underpinned the results related to empowerment. Second, we contrasted the data against the retained purposive selection of papers that included a mixture of participants with both advanced life-limiting disease and a range of other disease states/stages. We contrasted papers to observe and address any gaps, to ensure that the papers solely describing our population of interest were adequately addressing the subject matter, while also constantly testing and challenging our emerging theories against the available evidence for other patient populations. Third, we mapped the results to a variety of existing frameworks and models of empowerment originally designed for patients with long-term conditions and/or non-specific patient groups.4,5,16,23,24 This process, which involved repeated evaluation and testing of the data, created opportunities to observe whether interpretations altered when applying a variety of perspectives during the mapping process. This exposed the contrasting features of empowerment for our population of interest when compared to the patient groups represented by the models and frameworks. The mismatch between existing models and our data demonstrated the inadequacy of the models in describing patient empowerment in advanced disease and prompted our generation of a new conceptual model.

Of the included studies, 25% were randomly selected and dual coded (J.B. and D.W.) to enhance reliability alongside regular meetings to discuss all aspects of the design and conduct of this review (D.W. and F.E.M.M.).

Results

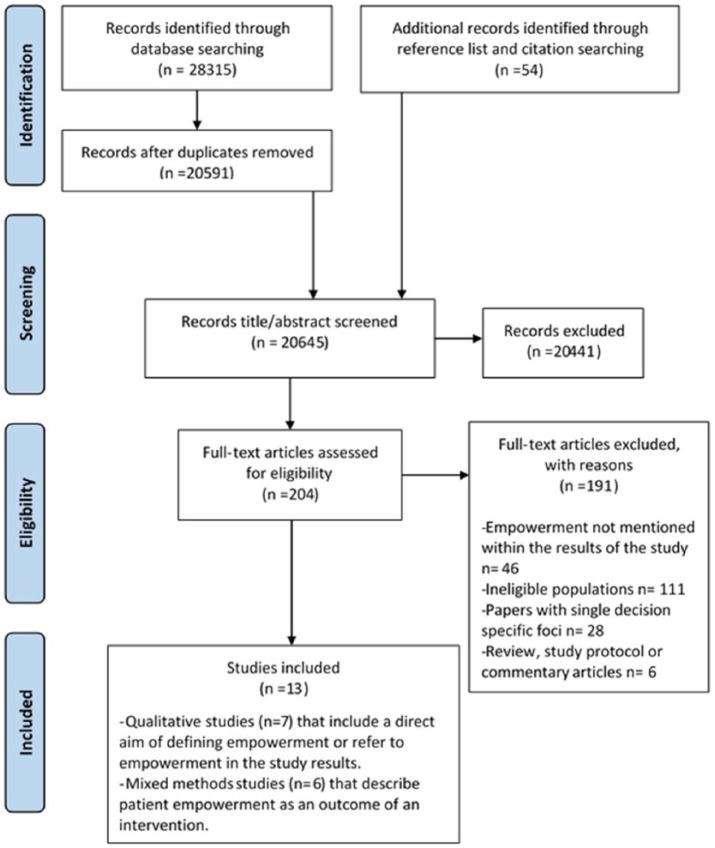

A total of 20,591 papers were screened, but only 13 papers met our inclusion criteria after quality assessment (Figure 1). Countries represented across the 13 papers were the United Kingdom (n = 5),25–29 the United States (n = 3),27,30,31 Australia (n = 3),31–33 Ireland (n = 2),27,34 the Netherlands (n = 1)35 and Norway (n = 1).36 There were seven qualitative studies and six mixed method studies, the characteristics of which are summarised in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Qualitative studies – results.

| Author Year Country |

Study design and data source informing findings | Participants | Findings relating to the process of becoming empowered | Findings relating to the state of being empowered | Challenges to empowerment. Disempowering processes/events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dong et al.32

2016 Australia |

Semi-structured interviews exploring patients’ experiences of having multiple symptomsa | 58 patients all with advanced metastatic cancer | Continuity and coordination of careb,c

HCPs communicating with compassionb Carers supporting patients psychological state(s)d |

Preserved dignityb,e

Preserved autonomyb,e Feeling secure and understoodb,e Accepting terminal diagnosise |

Feeling ‘abandoned’ by HCPsb |

| Etkind et al.25

2016 UK |

Secondary analysis of 30 qualitative interview transcripts exploring experiences of uncertaintya |

30 patients All ‘advanced’ disease (5 cancer and 25 non-cancer) |

Improve understanding around uncertaintyb,e

Improved communication around uncertaintyb |

||

| Harley et al.26

2012 UK |

Semi-structured interviews exploring and aiming to define chronic cancerf | 56 patients with advanced cancer | Self-managementb,e | Retaining and enhancing controle (via self-management) | |

| Olsman et al.35

2015 Netherlands |

Semi-structured interviews describing the relational ethics of hope based on the perspectives of participantsf |

29 palliative care patients, 19 friends/family members, and 52 HCPs | Protect hopeb

Appreciating the balance between compassion (suffering and loss of hope) and empowerment (hope and power)b,e HCP focus on hope (what still can be done)e HCP recognising patients power in spite of severe illnesse |

Hope and power recognised and supportedb | |

| Richardson et al.33

2010 Australia |

Qualitative interviews exploring empowerment and daily decision-makingaf | 11 Patients receiving palliative care in hospice (10 cancer) | Individual engagementb

‘Letting go’ to enable future care decisions and to allow others to helpb Accepting terminallyb Wanting to protect hopeb Coping with threats/changes to identity including physical appearance/imageb Need for preservation of routine – ADLsbe Daily involvement in basic and important decisionsb,d,e Preference for listening/being there versus someone constantly ‘doing’d,e Need for partnership between patients and HCPb,e Intentional efforts to create a more equitable relationship and a living within someone else’s worlde Empathic, listening relations between patients and carersb,d |

Being valued and respectedb

Retained control (from acceptance/acknowledgement)b Retained autonomyb Retained motivation to live (from preservation of ADLs)b,e |

No control over illness and time linked to progressionc

Burden/worry of being unable to sort affairsc Continued losses/forfeitures physical and socialc Continued threats to hopec Feeling ‘metaphorically’ abandonede Hospitals restricting autonomye |

| Schulman-Green et al.30

2011 USA |

Semi-structured interviews describe experiences of self-management in the context of transitionsa | 15 women with metastatic breast cancer | Self-management (including learning new skills)b,e | Able to self-managee

Able to self-manage during transitionse |

Difficulty obtaining informatione

Lack of knowledge regarding cancer trajectorye Constant transitions in condition status, evolving symptomsc |

| Selman et al.27

UK, Ireland and USA 2016 |

Ethnography including semi-structured interviews exploring challenges to and facilitators of empowerment across six hospitalsa |

26 older adults with advanced disease (receiving specialist palliative care) (20 cancer and 6 non-cancer) 32 unpaid caregivers and 33 hospital staff members |

Communication: time, listening, role explanations, openness and honestly concerning limitations of care and prognosisb

Tailoring Information and careb Preference seeking, exploring patients’ own idea of ‘autonomy’ with regard decision-makingb,e HCP to avoid abandoning patients with decision-makingb Continuity of care (avoid abandonment)c Relational care (team including patient and family as part of the team)b,d,e HCPs with expertise in care for patients with advanced diseaseb Well-resourced hospitalc Peaceful, attentive environment with privacyb,c Dignity-promoting initiativesb,c Timely access to specialist palliative carec HCPs thinking beyond routines, focusing on quality of life, protecting patient dignity, respecting privacyb |

Confident to ask for HCPs support/timed,e

Confidence for inclusione Feeling respected, valued and acknowledgede Individualism maintainede Informede Comfortable (environment)c |

Poor communication: too much information too soon, over-emphasis of patient autonomy, deferring to patient to make decisionsb

Fragmented care, Inadequate staffing levels and expertiseb,c Too many staff involved in care of one patientb Patients/caregivers not wanting to burden staffb,d Hospital is hierarchical, difficult to navigate, encourages compliance, makes patients vulnerable and nervous to communicate needsb,c Emphasise hospital discharge protocols and case management proceduresb,c |

ADLs: activities of daily living; HCPs: healthcare professionals; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Data source informing findings: results.

HCP qualities/capacities.

Environment factors.

Family/significant others qualities/capacities

Patient states/capacities.

Data source informing findings: patient quote/s.

Table 2.

Mixed methods studies- Results.

| Author Year Country |

Study design Data source informing findings |

Participants | Findings relating to the process of becoming empowered | Findings relating to the state of being empowered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clayton et al.31

2007 Australia |

RCT. Exploring whether a question prompt list influences advanced cancer patients’/caregivers’ questions and discussion of topics relevant to end-of-life care during palliative care consultationsa,b | 174 terminally ill cancer patients (92 intervention and 82 control) | Question prompt lists, aid/prompt dialogue with HCP enhancing communicationc,d | Confidence (and engagement) to ask HCPs questions about prognosis/future caree |

| Henriksen et al.28

2014 UK |

Mixed methods. Pilot study implementing a Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ). In a hospice in-patient settingb |

17 Hospice patients completed questionnaires. 9 patients and 1 relative completed interviews |

Opportunity to express opinionsd

Being involved in care decisions/experienced,e |

Being heardd

Opinions considered meaningfuld Feeling valuedd,e |

| Kane et al.34

2018 Ireland |

Semi-structured interviews exploring patients’ experience of using the Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale (IPOS) in heart failure clinicsa | 18 patients all with ‘advanced heart failure’ and 4 nurses | Validation of symptom experiencec,d,e

Holistic needs assessment supports, vocabulary and therein dialogue with HCPsc,d,e |

Enhanced feeling of control over illness through taking ownership of symptomse

Active (rather than passive) role in health care/managemente Confidencee Being more actively involved in clinical consultationsd,e |

| Maloney et al.37

2013 USA |

A qualitative descriptive study of participants’ perspectives of the intervention ENABLE II (Educate, Nurture, Advise Before Life Ends)a,b |

53 interview participants All advanced ‘palliative’ cancer |

Support/encouragement to seek helpd

Taking an active role in managing health-related issuese Planning for future deteriorations in healthe |

Confident to seeking assistance from HCPse

Active (rather than passive) role in health care/managemente Active (rather than passive) role in dealing with family and friendse Confident to communicate limitations/disability, informing family/HCPs what your able to doe |

| Mikkelsen et al.36

2015 Norway |

Semi-structured interviews exploring experience participation in a study focusing on lifestyle interventionsb | 9 ‘Palliative’ cancer patients | Gain knowledge of ‘illness’ situationc,d,e

Gain understanding of situationc,d,e HCPs providing education and an active learning environment motivates patients & strengthensd |

Confidencee

Enhanced feeling of control over illness and treatmentd,e Enhanced abilities to apply problem-focused copingd,e Managing disappointment when failing to achieve goalse |

| Reilly et al.29

2015 UK |

Questionnaire survey to describe patients’ experiences of a Breathlessness Support Service that included integrated palliative carea,b | 25 Patients with advanced disease and refractory breathlessness (6 cancer) | Education: understanding of illnessc,d,e

Education: understanding of symptom trajectory/progression of illnessc,d,e Skills: managing crises, symptom controlc,d,e Personalised care plan, with information, formulated by HCPsc,d |

Enhanced capacity to manage/control symptomse |

HCPs: healthcare professionals; RCT: randomised controlled trial.

Data source informing findings: intervention outcome.

Data source informing findings: results

Environment factors.

HCP qualities/capacities.

Patient states/capacities.

Data were of three types: patient quotes,27–29 the author’s words when discussing the study results25, 26, 29–33, 35–37 and the reported outcome/s of interventions. Of the 13 studies, 7 included participants with cancer diagnoses, while the remaining 6 included a mix of cancer and non-cancer patient groups. No discernible differences were identified between the cancer and non-cancer groups with respect to patient empowerment.

Two papers had the stated aim of exploring empowerment in our population of interest.27,33 We were unable to identify any interventions designed with the specific aim of empowering patients with advanced disease. Six papers evaluated interventions, referencing patient empowerment as an incidental outcome.28,29,31,34,36,37 The remaining five papers, referencing empowerment within their results, were qualitative studies exploring living with multiple symptoms,32 experiences of uncertainty,25 the concept of chronic cancer,26 relational ethics of hope35 and experiences of self-management.30

The interventions associated with empowering patient outcomes included single-component interventions (Question Prompt Lists, Patient Satisfaction Questionnaires and a Patient-Reported Outcome Measure) and complex interventions (Breathlessness Support Service, lifestyle interventions and multi-component educational and care management palliative care intervention).

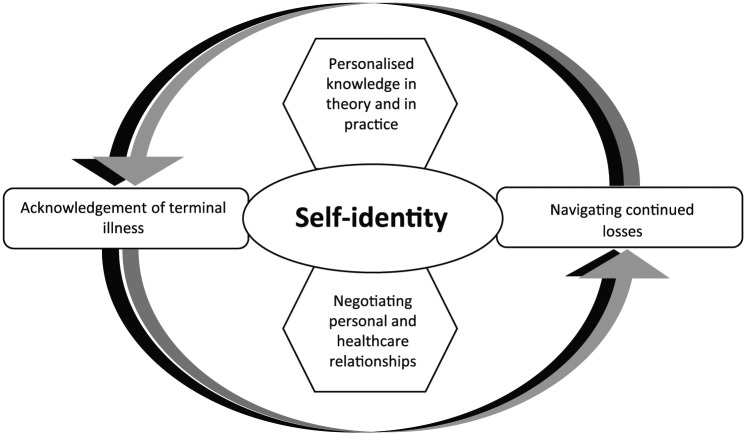

Our critical interpretative synthesis generated five overarching themes, illustrated in Table 3 (Appendix 2) and discussed in the following. The proposed conceptual model (Figure 2.) illustrates the interplay and relationships of these themes.

Figure 2.

Proposed conceptual model of patient empowerment for adults with advanced life-limiting illness.

Self-identity

Eight papers described the importance of self-identity as both a process to becoming empowered and being empowered. Self-identity, in the context of empowerment, reflects the beliefs a patient has about themselves, expressed, although not exclusively, in terms of self-esteem, self-image and ideal-self.

Maintaining routines, particularly with respect to personal-care activities, positively benefitted autonomy and self-esteem, reinforced by HCPs or families encouraging patient involvement in daily basic and important decisions. Maintaining a daily schedule was also described as a motivating element to ‘keep living in the face of death’.33 However, the ability for patients to control or partake in daily basic care activities was challenged by the timetabling of care and imposition of non-negotiable health and social care both in community and hospital settings.27,33 This blanket caregiving created a ‘defy or comply’ response from patients, depending on their strength and/or confidence to challenge professionals.33

Receiving the respect of others, reflected in being acknowledged, and being afforded privacy and inclusion despite disability were key features of empowerment.27,28,33,36 Experiencing overt changes to one’s physical appearance, described by one patient as ‘shrinking’, poses a significant threat to confidence and generates a fear that others will fail to recognise patients’ power, identity and capabilities as bodies transform.33

Personalised knowledge in theory and in practice

The need for personalised illness education that emphasises the pathophysiology of symptoms to support understanding of symptom management emerged as a component of becoming empowered. Merely providing knowledge and skills around symptom management was highlighted as insufficient.27 Personalised information provision, at the patient’s pace, that included the expected symptom trajectory and more generally ’what to expect’, was reportedly empowering.29,30

Mikkleson et al.36 report on the benefits of a ‘healthy’ lifestyle educational intervention, emphasising the continued desire to be ‘healthy’ and make ‘healthy choices’ even in the advanced stages of illness, as a mechanism for regaining control, which promoted confidence and coping. The need to personalise and pace these approaches was also reported after patients expressed feelings of guilt when failing to achieve mutually designed ‘goals’.36

In congruence with the findings from other patient populations, having knowledge and skills encouraged patient participation in self-management, enhancing confidence and renewing a sense of self-responsibility and motivation.26,29,34,36 In contrast, desire for self-management education was often tempered by the patient’s ‘ability’ to consider further, inevitable losses. In this patient group, self-management education should be delivered sensitively and in a personalised manner which respects changes in capacities, capabilities and priorities over time.

Negotiating personal and healthcare relationships

Eight studies explored features of personal and healthcare/professional relationships that enabled and sustained a sense of empowerment for patients. The qualities advocated applied to HCPs, families, informal carers, patients and services, with the synergy between these groups integral in the attainment of empowerment. Empowering partnerships were fostered by families and HCPs ‘being and listening’ rather than ‘doing’, reinforcing equality, respect and therein the patient’s self-identity.31–33,37 Central to these partnerships was engaging patients in their care rather than resigning them to a passive role in paternalistic, overly nurturing relationships. Owing to the deleterious effects of advancing disability, relationships and roles needed constant re-evaluation. In this context, empowered exchanges involved patients negotiating the offers of support from HCPs or families and protecting the proportion of the proposed activity that can be achieved independently.33,36

HCPs needed to communicate in an unrushed, empathic, honest and inclusive fashion,31,32 tailoring patient-centred decision-making to support the preferences and values of the patient over time. Clinicians over-emphasising patient choice/autonomy in efforts to empower patients (e.g. by ‘dumping’ information on them rather than collaborating in decision-making), conversely resulted in patients feeling abandoned and disenfranchised.31 In addition, respecting the preference of some patients to pass on responsibility for decision-making can be an empowering demonstration of wishes for patients.31

There is evidence that for some patients, desire for open and honest communication can be restricted by the fear of losing hope, based on either previous experience or an expectation of clinicians censoring hope when communicating with complete honesty in the context of life-limiting illness. This is reflected in the works of Richardson et al.33 and Olsman et al.35 where patients describe the desirable ability of HCPs to ‘protect hope’ to enable patients to retain a degree of positivity for the future in spite of their prognosis.

Possessing the confidence to seek help from others, both family and HCPs, was also a feature of empowerment.28,31,34,36,37 Obtaining permission to seek the help was intrinsic to this process, three of the included studies described interventions that supported patients’ interaction and discussions with HCPs.31,34,37

Acknowledgement of terminal illness

Studies described a point where by patients acknowledged their impending death, inclusive of the stark realities of what that might mean for their physical and mental capacities, in order to regain a sense of control. In this context, control was signified through sorting affairs and making decisions in response to the limitations placed on their life expectancy.25 Control was also manifested through patient-led ‘handing over’ of physical tasks to family or HCPs to facilitate the reassignment of energy to alternative tasks/focuses.33 While one study stated that empowerment could not truly be achieved without people acknowledging their mortality and the consequences of progressive disability,30 others provided examples of patients feeling empowered, having stated their wish to avoid discussions around their mortality and future losses.33

Navigating continued losses

Adaptation to, and coping with, continuous physical and social losses was cited as a key feature of becoming and being empowered in five papers. Adaptation was achieved through changing priorities, sorting personal affairs and planning for further deteriorations.25,27,30 Coping involved refocusing on small daily tasks.33

Having hope was central to the patient’s capacity for adaptation and coping, with hope a motivating element to ‘go on’ as losses continued to manifest.33 The fragility of hope and therein one’s ability to cope and continue was recognised as being under continuous threat.30

Possessing the skills and capacity to continually adapt, and remain resilient to, loss provided opportunity to achieve or regain a sense of feeling ‘in control’.30 The presence or absence of control thus emerged as a key moderator to being or becoming empowered.

Themes within the conceptual model

‘Self-identity’, as a central feature of patient empowerment, includes preserving, enhancing and communicating self-identity. It reflects the importance placed on identity for self (the patient), relationships and society. In the theoretical model, each theme has a potentially mutually influential relationship with self-identity.

An example of this is demonstrated by Richardson et al. in their qualitative interview study exploring issues surrounding empowerment and daily decision-making with 11 terminally ill hospice in-patients. Patients associated negotiating offers of care and inclusion in therapeutic relationships with strengthened self-identity; this mitigated the challenges to self-image and self-identity produced by the negative appearance-altering manifestations of their illness.33

Olsman et al. investigated the relationship between hope and empowerment through interviews with 29 patients receiving specialist palliative care support. Patients needed HCPs to convey hope of what still can be done. Patients ‘having hope’ were protective against the reality of terminal illness, including potential functional losses. Retaining hope consequently enhanced capacities to acknowledge and manage transitions in their illness and made patients feel more powerful. This resulted in HCPs ‘recognising patients own power, in spite of severe illness’.35

‘Acknowledgement of terminal illness’ and ‘Navigating continued losses’ themes within the model represents features felt by patients to be inescapable in the advanced stages of life-limiting illness. These, like all the themes identified, were expressed to different degrees within the literature. An example is provided by Olsman et al.35 when a patient, not wishing to acknowledge her terminal diagnosis with HCPs, communicated this preference to help negotiate these relationships and felt empowered as a result.

‘Personalised knowledge in theory and in practice’ and ‘Negotiating personal and healthcare relationships’ include features of empowerment conceptualised as being optional for patients to engage with and, when engaged, open to influence by patients themselves.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

To our knowledge, this is the first review to explore the concept of patient empowerment for adults living with advanced, life-limiting illness. Principally, we have identified that while there is a paucity of research in this area, the evidence available demonstrates the differences in the factors/themes associated with patient empowerment for adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness in comparison to other patient groups. Key differences relate to the continued physical and psychosocial challenges this group encounter, producing contrasting patient empowerment foci and outcomes.

Distinct for our population of interest is the experience of continued insults and resultant losses that occur within short periods of time. Empowerment, when you are dying, includes the capacity to withstand insults and losses which may compromise, in particular, a patient’s self-identity. Protecting self-identity is central to empowerment for this group and represents a key motivator to ‘continue living’,33 in comparison to other patient groups, where enhanced or sustained health states are seen as both a motivator and outcome of empowerment.4,38,39

From the literature focused on patients with long-term conditions (the group that empowerment strategies have largely evolved to target), a key empowerment outcome is aimed towards enhancing patients ‘feelings of control over their illness’.5,13,15 In contrast, an outcome or focus for empowered patients with terminal illness appears to centre around self-identity, as opposed to control of their illness or health state(s). For example, this review found that patients placed stronger emphasis on the benefits of equitable therapeutic relationships with HCP with respect to self-identity (feeling respected and valued),27,33,35 rather than focusing on the product of that relationship being to enhance their ‘feelings of control over their illness’.

Furthermore, relationships with HCP and families, for this group, evolve more readily owing to persistent losses and often inevitable physical or cognitive dependency. There is a delicate need for shifting responsibilities over time, with points at which the patient ‘hands over’ increasingly to others. Recognising evolving physical limitations and letting others ‘do’ can instil a sense of control so long as it is balanced and paced to the patients preference and is not restricted by timetabled, non-personalised care. This is in contrast to the focus on persistently equal relations and responsibilities for HCP/families and patients in other groups.4,7,15

Our review identified just two papers that sought to explore empowerment as a study objective.27,33 Richardson et al. explored the meaning of empowerment and decision-making from the perspectives of 11 patients in receipt of specialist palliative care support, while Selman et al. studied the challenges to and facilitators of empowerment in an ethnographic study interviewing 26 patients aged ⩾65 years receiving specialist palliative care. Both papers communicate the emphasis placed, by patients, on relationships and services that enable them to attain and retain respect, acknowledgement and inclusion.

We did not identify any papers evaluating interventions designed to empower patients with advanced disease. The five mixed method studies that evaluated interventions referenced empowerment as an incidental outcome. In contrast, Bravo et al.4 identified 67 studies with published definitions of patient empowerment for patients with long-term conditions. Barr et al.5 identified 30 studies on 19 measures of empowerment for a range of patient groups, although none designed specifically for patients with advanced, life-limiting conditions.

Limitations

The terms ‘patient empowerment’ and ‘patient activation’ largely occur within research and policy in developed, high-income countries and might not translate across all countries and cultures. We retained studies that exclusively included and defined patients as being in the advanced stages of life-limiting illness. Not all papers report the phase/stage of illness of participants, so we might have missed papers that might have contributed to the aims of this study.

Implications for policy, research and practice

Our review found no evidence of attempts to incorporate patient empowerment into the design or evaluation of services that support people with advanced life-limiting illness. In contrast, there is a significant body of work in this area for patients with long-term conditions and as part of population health-promotion strategies.12,13,40,41

We suggest, based on the findings from this review, that current programmes and measures of patient empowerment may not be wholly applicable to patients with advanced, life-limiting disease. First, many of these existing approaches assume a role for prevention of negative health states or promotion of lifestyle measures to benefit health states.15 Second, there is little research addressing and/or managing the irreversible aspects of health states.40 Third, there may be additional dimensions and aspects of empowerment in advanced illness, as described in the opening of our discussion. On this basis, we would argue that presently there is no reliable and valid way to assess whether existing services and structures are or are not empowering to patients with advanced, life-limiting disease.

The findings of this review highlight the desire of many patients to remain actively involved in decisions about, and in the practice of, their care. To this effect, we suggest that services should aim to support and promote empowerment. The emerging use of discrete choice experiments in service assessment and design42,43 may offer a method to maintain patient inclusion and support the generation of services that will benefit patient empowerment in tandem. In addition, interventions shown to empower patients should be incorporated into routine practice; these include interventions that support patient and HCP dialogue28,31 and involve personalised lifestyle and self-management advice.29,36,37

Conclusion

This review provides an evidence base and conceptual model to inform future research into patient empowerment for patients with advanced life-limiting illness. Being an ‘empowered patient’, when living with advanced life-limiting illness is different to the experience and meaning of empowerment for other patient groups. ‘Patient empowerment’ emerges as a metaphor for all that enables people to maintain their self-identity until the very end of life.

Considering the benefits of services and programmes designed to empower patients in other groups, further research is needed to ensure end-of-life care is optimally empowering. We would propose that the themes of this review may provide a useful starting point to guide the assessment of existing services and development of a new dialogue surrounding patient participation in the design of services and interventions.

Acknowledgments

D.W. is the lead of the design and development of the study to include the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. Lead author involved in drafting and revising the article and approved the version to be published. F.E.M.M. contributed to the study design, analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the article and approved the version to be published. J.B. contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision of the article and approved the version to be published. L.S., A.M.F. and I.J.H. critically revised the article and approved the version to be published.

Appendix 1

- Database search details and search terms used for review

- MEDLINE via Ovid (Inception to week 2 March 2018)

- EMBASE via Ovid (Inception to week 2 March 2018)

- CINAHL via EBSCOhost (Inception to week 2 March 2018)

- PsycINFO via Ovid (Inception to week 2 March 2018)

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Inception to week 2 March 2018)

Medline (OVID) search strategy

| Search terms | |

|---|---|

| 1 | *Patient Participation/ |

| 2 | *Self Care/ |

| 3 | empowerment.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] |

| 4 | *Self Efficacy/ |

| 5 | mastery.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] |

| 6 | *Self-Control/ |

| 7 | control.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] |

| 8 | *Self Concept/ |

| 9 | *Internal-External Control/ |

| 10 | confidence.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] |

| 11 | *Decision-Making/ |

| 12 | *Attitude to Health/ |

| 13 | *Motivation/ |

| 14 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 |

| 15 | end-of-life*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] |

| 16 | (advanced adj3 (disease or condition or illness)).mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] |

| 17 | (progressive adj3 (disease or condition or illness)).mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] |

| 18 | palliat$.tw. |

| 19 | hospice$.tw. |

| 20 | *Palliative Care/ |

| 21 | *Terminal Care/ |

| 22 | *Terminally Ill/ |

| 23 | *Hospices/ |

| 24 | terminal-care.tw. |

| 25 | (activat* or partcipat* or empower* or engag* or decision* or self* or confiden* or master* or belie*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] |

| 26 | *Death/ |

| 27 | *Bereavement/ |

| 28 | 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 26 or 27 |

| 29 | 14 and 28 |

| 30 | 25 and 29 |

3. Search terms by database

| Search terms – Medline (OVID) *MeSH heading .mp. = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] | |

| *Patient Participation *Self Care *Self Efficacy *Self-Control *Self Concept *Internal-External Control *Decision-Making *Attitude to Health *Motivation empowerment.mp. mastery.mp. control.mp. confidence.mp. |

*Palliative Care *Terminal Care *Terminally Ill *Hospices *Death *Bereavement end-of-life*.mp. (advanced adj3 (disease or condition or illness)).mp. (progressive adj3 (disease or condition or illness)).mp. (activat* or partcipat* or empower* or engag* or decision* or self* or confiden* or master* or belie*).mp. terminal-care.tw. palliat$.tw. hospice$.tw. |

| Search terms – Embase(OVID) *MeSH heading .mp. = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword | |

| *Patient Participation *Self Care *Self Efficacy *Self-Control *Self Concept *Internal External Locus of Control *Decision-Making *Health Attitudes *Motivation empowerment.mp. mastery.mp. control.mp. confidence.mp. |

*Palliative Care *Terminal Care *Terminally Ill Patients *HOSPICE *‘death and dying’ *Bereavement end-of-life*.mp. (advanced adj3 (disease or condition or illness)).mp. (progressive adj3 (disease or condition or illness)).mp. (activat* or partcipat* or empower* or engag* or decision* or self* or confiden* or master* or belie*).mp. terminal-care.tw. palliat$.tw. hospice$.tw. |

|

Search terms – PsycINFO (OVID)

*MeSH heading .mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword] | |

| *Patient Participation *Self Care *Self-Control *Self Concept *Control *Decision-Making *Attitude to Health *Motivation empowerment.mp. mastery.mp. control.mp. confidence.mp. |

*palliative therapy *Terminal Care *terminally ill patient *Hospices *Death *Bereavement end-of-life*.mp. (advanced adj3 (disease or condition or illness)).mp. (progressive adj3 (disease or condition or illness)).mp. (activat* or partcipat* or empower* or engag* or decision* or self* or confiden* or master* or belie*).mp. terminal-care.tw. palliat$.tw. hospice$.tw. |

| Search terms – CINAHL (EBSCO) MM – Searches the exact CINAHL® subject heading; searches just for major headings, MW – Searches for a word in the CINAHL® subject heading, including subheadings, retrieves citations indexed under major or minor. Article Title (TI), Abstract (AB), Within three words of (n3) | |

| ‘patient participation’ (MM ‘Self Care’) (MM ‘Self-Efficacy’) (MM ‘self control’) (MM ‘Self Concept’) (MM ‘Locus of Control’) (MM ‘Decision Making, Patient’) (MM ‘Attitude to Health’) (MM ‘Motivation’) (MM ‘Attitude to Illness’) (MM ‘Empowerment’) (MM ‘mastery’) (MM ‘Confidence’) |

(MM ‘Palliative Care’) (MM ‘Terminal Care’) (MM ‘Terminally Ill Patients’) (MM ‘Hospices’) (MM ‘Death’) *Bereavement/ ‘end of life*’ TI ( ((advanced) n3 (disease* or condition* or illness*)))) OR AB ( ((advanced) n3 (disease* or condition* or illness*)))) TI ( ((progressive) n3 (disease* or condition* or illness*))) OR AB ( ((progressive) n3 (disease* or condition* or illness*))) TI ( (activat* or partcipat* or empower* or engag* or decision* or self* or confiden* or master* or belie*)) OR AB ( (activat* or partcipat* or empower* or engag* or decision* or self* or confiden* or master* or belie*)) OR MW ( (activat* or partcipat* or empower* or engag* or decision* or self* or confiden* or master* or belie*)) ‘“terminal-care”’ ‘palliat*’ ‘hospice*’ |

Appendix 2

Table 3.

Study findings related to empowerment mapped to themes.

| Self-identity | Personalised knowledge in theory and in practice | Acknowledgement of terminal illness | Negotiating personal and healthcare relationships | Navigating continued losses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preserved dignity32

Feeling respected35 Privacy27 Desire for respect, being valued, acknowledged27 Being valued and respected33 Preserve autonomy33 Feeling valued ‘useful’36 Confidence36 Managing planned activities36 Ability to perform & maintain personal care33 Need for preservation of routine ADLs > to keep motivation to live33 Individual engagement 33 Confidence34 Daily involvement in basic and important decisions 33 Opinions being valued28 Self-Control26 Preserved autonomy32 |

Validation of symptom experience34

Enhanced feeling of control over illness through taking ownership of symptoms34 Health ‘situation’-knowledge36 Health ‘situation’-understanding36 Self-management promoting a sense of ‘control’26 Self-management30 ‘Healthy’ Lifestyle education > control, confidence,coping36 Self-management (obtaining knowledge and skills)30 Understanding of illness29 Understanding of symptom trajectory29 Illness education29 Balance of goal setting being motivating-confidence, coping-when achieved but equally36 Guilt on failing to reach goals and a loss of motivation36 |

Accepting the need for assistance/help33

Acknowledge disease progression > control to sort affairs33 Acknowledge and Accept lack of control over course of illness > control and autonomy33 Acknowledge uncertainty26 Accepting terminal diagnosis32 Address and Sort affairs26 Planning for future deteriorations in health36 |

Continuity and coordination of care32

HCPs communicating with compassion32 Carers supporting patients psychological state(s)32 HCPs protecting hope35 Need for partnerships with HCPs33 Empathic, active listening relationships33 Preference for listening/being vs people ‘doing’ 33 Feeling supported 33 HCPs to avoid abandoning patients with decision-making27 Opportunity to discuss preferences27 Exploring patient’s own idea of ‘autonomy’27 Unrushed communication with HCPs27 Obtain preferences for decision-making27 Confidence for inclusion27 Confident to ask for support and time from HCPs30 Honest communication with HCPs27 Holistic needs assessment supports, vocabulary and therein dialogue with HCPs34 Question prompt lists aid and/or prompts dialogue30 Being involved in care decisions/experience28 Feeling secure and understood32 Being heard28 Express opinions28 Confidence to ask HCPs about prognosis/future care30 Confidence to seeking assistance from HCPs31 Support/encouragement to seek help31 Discussions, rather than ‘consultations’30 Being confident to express limitations/disability35 |

Hope as a motivator, to ‘go on’/stay alive33

Accept uncertainty25 Coping36 Changing priorities33 Resilience to/coping with threats to hope33 Adaptation to continued losses/forfeitures physical and social33 Adapting to physical/self-image changes33 Power to manage losses – regaining internal control33 Taking an active role in health-related issues – planning for future deteriorations in health36 Coping with the impacts of shrinking body/bodily functions on identity33 Hope35 Power35 Active (rather than passive) role in health care/management34 |

ADLs: activities of daily living; HCPs: healthcare professionals.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: This paper presents independent research part-funded through a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Integrated Academic Training Fellowship (DW is an NIHR-funded Academic Clincial Fellow). The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Health Service, the National Institute of Health Research, Medical Research Council, Central Commissioning Facility, NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, the National Institute of Health Research Programme Grants for Applied Research, or the Department of Health.

Research ethics and patient consent: This study uses routinely collected, aggregated and anonymised data that are publicly available, and therefore, no ethical approvals were necessary.

ORCID iDs: Dominique Wakefield  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9800-0436

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9800-0436

Lucy Selman  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5747-2699

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5747-2699

Irene J Higginson  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1426-4923

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1426-4923

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Observatory data – life expectancy, www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/life_tables/situation_trends_text/ (2017, accessed 20 June 2017).

- 2. Anderson G, Horvath J. The growing burden of chronic disease in America. Public Health Rep 2004; 119(3): 263–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO). Global health and aging, www.who.int/ageing/publications (2011, accessed 20 June 2017).

- 4. Bravo P, Edwards A, Barr PJ, et al. Conceptualising patient empowerment: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv Res 2015; 15(1): 252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barr PJ, Scholl I, Bravo P, et al. Assessment of patient empowerment-a systematic review of measures. PLoS ONE 2015; 10(5): e0126553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anderson RM, Funnell MM. Patient empowerment: reflections on the challenge of fostering the adoption of a new paradigm. Patient Educ Couns 2005; 57(2): 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alexander JA, Hearld LR, Mittler JN, et al. Patient-physician role relationships and patient activation among individuals with chronic illness. Health Serv Res 2012; 47(3 Pt 1): 1201–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Fitzgerald JT, et al. The Diabetes Empowerment Scale: a measure of psychosocial self-efficacy. Diabetes Care 2000; 23(6): 739–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCorkle R, Ercolano E, Lazenby M, et al. Self-management: enabling and empowering patients living with cancer as a chronic illness. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61(1): 50–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wallerstein N. What is the evidence on effectiveness of empowerment to improve health? Health evidence network report, February 2006, p. 37, http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/74656/E88086.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11. Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 2012; 27(5): 520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. NHS England. New care models: empowering patients and communities, www.england.nhs.uk (2015, accessed 24 April 2017).

- 13. EMPATHiE Consortium. EMPATHiE empowering patients in the management of chronic diseases. Report produced under the EU Health Programme, http://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health (2014, accessed 20 June 2017).

- 14. Hibbard JH, Cunningham PJ. How engaged are consumers in their health and health care, and why does it matter. Res Brief 2008; 8: 1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hibbard J, Gilburt H. Supporting people to manage their health. The Kings Fund, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk (2014, accessed 20 June 2017).

- 16. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004; 39(4): 1005–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wakefield D, Bayly J, Selman L, et al. Patient empowerment, what is it and what does it mean for adults in the advanced stages of a life-limiting illness? A systematic review and critical interpretive synthesis of existing evidence to inform palliative care. PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42016046113), 2016, http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016046113

- 18. Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006; 6(1): 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aujoulat I, d’Hoore W, Deccache A. Patient empowerment in theory and practice: polysemy or cacophony? Patient Educ Couns 2007; 66(1): 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sladek RM, Tieman J, Currow DC. Improving search filter development: a study of palliative care literature. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2007; 7(1): 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brereton L, Clark J, Ingleton C, et al. What do we know about different models of providing palliative care? Findings from a systematic review of reviews. Palliat Med 2017; 31: 781–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luckett T, Phillips J, Agar M, et al. Elements of effective palliative care models: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14(1): 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen J, Mullins CD, Novak P, et al. Personalized strategies to activate and empower patients in health care and reduce health disparities. Health Educ Behav 2016; 43(1): 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bulsara C, Styles I, Ward AM, et al. The psychometrics of developing the patient empowerment scale. J Psychosoc Oncol 2006; 24(2): 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Etkind SN, Bristowe K, Bailey K, et al. How does uncertainty shape patient experience in advanced illness? A secondary analysis of qualitative data. Palliat Med 2017; 31(2): 171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harley C, Pini S, Bartlett YK, et al. Defining chronic cancer: patient experiences and self-management needs. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015; 5(4): 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Selman LE, Daveson BA, Smith M, et al. How empowering is hospital care for older people with advanced disease? Barriers and facilitators from a cross-national ethnography in England, Ireland and the USA. Age Ageing 2016; 46(2): 300–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Henriksen KM, Heller N, Finucane AM, et al. Is the patient satisfaction questionnaire an acceptable tool for use in a hospice inpatient setting? A pilot study. BMC Palliat Care 2014; 13(1): 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reilly CC, Bausewein C, Pannell C, et al. Patients’ experiences of a new integrated breathlessness support service for patients with refractory breathlessness: results of a postal survey. Palliat Med 2016; 30(3): 313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schulman-Green D, Bradley EH, Knobf MT, et al. Self-management and transitions in women with advanced breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011; 42(4): 517–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25(6): 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dong ST, Butow PN, Tong A, et al. Patients’ experiences and perspectives of multiple concurrent symptoms in advanced cancer: a semi-structured interview study. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24(3): 1373–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Richardson K, MacLeod R, Kent B. Ever decreasing circles: terminal illness, empowerment and decision-making. J Prim Health Care 2010; 2(2): 130–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kane PM, Ellis-Smith CI, Daveson BA, et al. Understanding how a palliative-specific patient-reported outcome intervention works to facilitate patient-centred care in advanced heart failure: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2017; 32(1): 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Olsman E, Willems D, Leget C. Solicitude: balancing compassion and empowerment in a relational ethics of hope – an empirical-ethical study in palliative care. Med Health Care Philos 2016; 19: 11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mikkelsen HE, Brovold KV, Berntsen S, et al. Palliative cancer patients’ experiences of participating in a lifestyle intervention study while receiving chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs 2015; 38(6): E52–E18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maloney C, Lyons KD, Li Z, et al. Patient perspectives on participation in the ENABLE II randomized controlled trial of a concurrent oncology palliative care intervention: benefits and burdens. Palliat Med 2013; 27(4): 375–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chatzimarkakis J. Why patients should be more empowered: a European perspective on lessons learned in the management of diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010; 4(6): 1570–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bann CM, Sirois FM, Walsh EG. Provider support in complementary and alternative medicine: exploring the role of patient empowerment. J Altern Complement Med 2010; 16(7): 745–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Segal L. The importance of patient empowerment in health system reform. Health Policy 1998; 44(1): 31–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wong CK, Wong WC, Lam CL, et al. Effects of Patient Empowerment Programme (PEP) on clinical outcomes and health service utilization in type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care: an observational matched cohort study. PLoS ONE 2014; 9(5): e95328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Douglas HR, Normand CE, Higginson IJ, et al. A new approach to eliciting patients’ preferences for palliative day care: the choice experiment method. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005; 29(5): 435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hall J, Kenny P, Hossain I, et al. Providing informal care in terminal illness: an analysis of preferences for support using a discrete choice experiment. Med Decis Making 2014; 34(6): 731–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]