Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a highly relevant clinical condition that is characterized by the permanent loss of functional nephrons. Individuals with CKD may exhibit impaired renal clearance, which may alter corporal handling of metabolites and xenobiotics. Methylmercury (MeHg) is an important environmental toxicant to which humans are exposed to on a regular basis. Given the prevalence of CKD and ubiquitous presence of MeHg in the environment, it is important to understand how mercuric ions are handled in patients with CKD. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to characterize the disposition of MeHg over time in a rat model of CKD (i.e., 75% nephrectomized (NPX) rats). Control and NPX rats were exposed intravenously (iv) to a non-nephrotoxic dose of MeHg (5mg/kg) once daily for one, two, or three days and the amount of MeHg in organs, blood, urine, and feces determined. The accumulation of MeHg in kidneys and blood of controls was significantly greater than that of NPX animals. In contrast, MeHg levels in brain and liver of controls were not markedly different from corresponding NPX rats. In all organs examined, accumulation of MeHg increased over the course of exposure, suggesting that urinary and fecal elimination are not sufficient to fully eliminate all mercuric ions. The current findings are important in that the disposition of mercuric ions in rats with normal renal function versus renal insufficiency following exposure to MeHg for a prolonged period differ and need to be taken into account with respect to therapeutic management.

Keywords: Kidney, Methylmercury, Chronic Kidney Disease, Nephrotoxicant

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common condition characterized by a progressive loss of functional nephrons and decrease in overall glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Chronic kidney disease, which may lead to end stage renal disease, affects approximately 15% of adults in the United States (CDC 2017). This renal disease has become an important global clinical entity as its prevalence has increased significantly over the past few decades (Rhee and Kovesdy 2015). In fact, CKD is now ranked as the 9th leading cause of death in the United States (CDC, 2017) and is 15th in the list of worldwide causes of death (GBD Collaborators. 2017). Development of CKD is most often associated with obesity, hypertension, and diabetes (CDC 2017). The American Heart Association estimates that approximately 69% of adults in the United States are overweight or obese; 33.5% of adults are hypertensive, and 9.3% of the adult population are diabetic (Mozaffarian et al. 2015). Therefore, a large fraction of the population is at risk of developing CKD.

Interestingly, the renal system displays a unique ability to compensate for loss of renal mass. As diseased nephrons become sclerotic and non-functional, the remaining functional nephrons undergo changes that enable these nephrons to compensate for reductions in renal mass. These compensatory changes are characterized by glomerular and cellular hypertrophy, enhanced expression of mRNA encoding numerous proteins, elevation in renal plasma flow to individual glomeruli, and increased single nephron glomerular filtration rate (SNGFR) (Fine et al 1992). While these compensatory changes are necessary to facilitate reabsorption of nutrients by the remaining functional nephrons, these alterations may also lead to enhanced uptake and accumulation of toxicants and other xenobiotics at the site of the hypertrophied tubule. In spite of the compensatory changes that occur at the site of the single nephron, renal disease often continues to progress and renal clearance declines over time. Changes in renal plasma flow and overall GFR may exert significant effects on corporal handling of toxicants and other xenobiotics.

One toxicant of particular concern is mercury (Hg). Humans are exposed to various forms of Hg, particularly methylmercury (MeHg) through environmental, dietary and occupational sources (Carneiro et al, 2014; Branco et al, 2017). The primary route by which humans are exposed to MeHg is via consumption of contaminated freshwater and saltwater fish (ATSDR 2008). The consumption of long-lived fish, predatory fish such as tuna and swordfish is especially concerning due to the fact that mercuric ions bioaccumulate in tissues of these fish. Despite guidelines from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regarding the consumption of certain species of fish (FDA 2017), many individuals, particularly those of Asian descent, continue to consume more than the recommended amount of fish. Within the United States, individuals of Japanese and Korean descent were found to exhibit significantly greater fish consumption and higher Hg intake levels than the national average (Tsuchiya et al. 2008). Perez et al (2012) found in Asian community in Philadelphia that although awareness of fish advisories improved, fish consumption remained unchanged. It also needs to be considered that Hg levels in fish may vary significantly among bodies of water across the United States; therefore, published fish advisories may not be appropriate for every location (Wolff et al. 2016; Taylor and Williamson 2017).

Considering the prevalence of CKD and continued consumption of Hg-containing fish, it is worthwhile noting that patients with CKD may continue to be exposed to MeHg. The manner in which mercuric ions are handled and accumulate in patients with CKD is likely to be different than that of patients with normal renal function. There are currently no apparent reports describing accumulation of mercuric ions in CKD patients; however, data from experimental models suggest that a 50% reduction in renal mass alters the disposition of mercuric ions (Bridges and Zalups, 2017; Lash et al. 2005; Oliveira et al. 2016; Zalups and Lash 1990). Animals that have undergone uninephrectomies are not usually in a state of renal insufficiency. Since the purpose of the current study was to characterize the handling of mercuric ions in animals with normal renal function and those with renal insufficiency, a 75% nephrectomized rat model was used to characterize the disposition of mercuric ions in CKD patients following multiple exposures to MeHg.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (16-18 weeks old, weighing 300-350 g) were obtained from our colony in the animal facility at Mercer University School of Medicine. The animals were provided a commercial lab diet (Tekland 6% rat diet, Envigo) and water ad libitum throughout the experiment. Animals were selected randomly and placed into 6 groups composed of 3-5 rats/group (Table 1). Rats in Groups 2, 4, and 6 underwent a 75% nephrectomy (NPX) surgery following previously published protocol (Zalups and Bridges, 2010). Rats in Groups 1, 3, and 5 were utilized as non-surgical controls. Previous studies indicated that there is no marked difference in handling of mercuric ions between non-surgical controls and sham-operated controls (Lash et al. 1999). Non-surgical controls are referred to simply as “controls” throughout this study. The animal protocol for the current study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were handled in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, adopted by the National Institutes of Health.

Table 1.

Dosing regime and euthanasia schedule

| Group | Day 0 | Day 1 (24 hr) | Day 2 (48 hr) | Day 3 (72 hr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: Control | Injected with MeHg | Euthanized | Euthanized | Euthanized |

| Group 2: NPX | Injected with MeHg | Euthanized | Euthanized | Euthanized |

| Group 3: Control | Injected with MeHg | Injected with MeHg | Euthanized | Euthanized |

| Group 4: NPX | Injected with MeHg | Injected with MeHg | Euthanized | Euthanized |

| Group 5: Control | Injected with MeHg | Injected with MeHg | Injected with MeHg | Euthanized |

| Group 6: NPX | Injected with MeHg | Injected with MeHg | Injected with MeHg | Euthanized |

Surgery

Wistar rats undergoing the 75% nephrectomy surgery were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (ip) injection of ketamine (70 mg/kg) and xylazine (6 mg/kg), following which, an incision was made down the ventral midline through the skin and musculature. The right kidney was isolated from the perinephric fascia and renal artery, renal vein, and ureter were ligated with 4-0 silk suture. The right kidney was removed completely without injuring the liver and adrenal gland. Subsequently, the posterior branch of the left renal artery was ligated with 2-0 silk suture as to eliminate blood supply to approximately 50% of the nephrons. The eventual result of this surgical procedure is an experimental rat model of kidney disease with approximately 25% functional renal mass. The NPX animals were allowed a 3-4 week recovery period prior to administration of mercury.

Manufacture of radioactive methylmercury (Me[203Hg])

The protocol for manufacturing radioactive mercury [203Hg] has been described previously (Belanger et al. 2001; Bridges et al. 2004). Approximately three milligrams of enriched mercuric oxide were placed in quartz tubing and irradiated by neutron activation for four weeks at the Missouri University Research Reactor (MURR) facility. The mercuric oxide was subsequently dissolved in 1N HCl and the radioactivity of the solution was measured using a Victoreen Ion Chamber Survey Meter. The specific activities of the [203Hg] fell in the range of 6 to 12 mCi/mg.

Me[203Hg] was formed following a previously established protocol (Bridges et al. 2009) adapted from Rouleau and Block (1997). Briefly, 2 mCi of [203Hg] (approximately 1.25 μmol) were added to sodium acetate (2 M in acetic acid) and 2 ml 1.55 mM methylcobalamin (3.1 mmol), which served as the donor of methyl groups. Following a 24-hr incubation period, potassium chloride (30% in 4% HCl) was added to the solution and Me[203Hg] was extracted with 5 washes of dicholoromethane (DCM). DCM was evaporated by bubbling nitrogen gas into the CH3Hg solution. The specific activity of the collected Me[203Hg] was approximately 5 mCi/mg and purity was confirmed previously by thin layer chromatography (Rouleau and Block 1997).

Intravenous Injections

All animals, non-surgical control rats (“control”) and NPX rats, were injected intravenously (i.v.) with CH3HgCl (5 mg/kg in 2 ml normal saline) according to a previously established protocol (Zalups 1993). Each injection contained 1 μCi of Me[203Hg]. At the time of injection, each animal was anesthetized with vaporized isoflurane (5% in oxygen) and an incision was made in the skin in the mid-ventral region of the thigh to expose the femoral vein. The calculated dose of CH3HgCl was administered and the wound was closed with two 9-mm wound clips. Following injection with CH3HgCl, animals were caged individually in metabolic cages to collect feces and urine.

Twenty-four hr (Day 1) after initial injection, animals from Group 1 (control) and Group 2 (NPX) were euthanized (Table 1). The remaining animals in Groups 3-6 were injected with another dose of CH3HgCl as described above. Forty-eight hr (Day 2) after the first injection of CH3HgCl, animals from Group 3 (control) and Group 4 (NPX) were euthanized. Groups 5 and 6 were injected with a third dose of CH3HgCl. Seventy-two hr (Day 3) following initial injection animals from Group 5 (control) and Group 6 (NPX) were euthanized. Multiple dosing was utilized in this study as a means to mimic short-term, yet repeated, exposures to MeHg such as repeated occupational exposure to mercuric compounds and/or repeated ingestion of contaminated food.

Collection of tissues, organs, urine, and feces

At the time of euthanasia, rats were anesthetized with an ip injection of ketamine and xylazine (70/6 mg kg−1). A 3-ml sample of blood was first collected from the inferior vena cava and 1 ml placed in a polystyrene tube for estimation of Me[203Hg] content. In order to determine the content of Me[203Hg] in plasma, 0.5 ml blood sample was placed in a blood separation tube to separate cellular contents of blood from plasma. The creatinine content of the plasma was assessed using a Creatinine Assay kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BioAssay). The total blood volume was estimated to be 6% of body weight (Lee and Blaufox 1985).

In controls, right and left kidneys were excised for determination of Me[203Hg] content. In NPX animals, the remnant kidney (NPX kidney) was extracted for estimation of Me[203Hg] content. Each kidney was trimmed of fat and fascia, weighed, and cut in half along the mid-traverse plane. A 3-mm transverse slice from one half of the left kidney was utilized to obtain samples of cortex, outer stripe of outer medulla (OSOM), inner stripe of outer medulla (ISOM), and inner medulla. Each zone of the kidney was weighed and placed in a separate polystyrene tube for estimation of Me[203Hg] content. The remaining half of the left kidney was placed in a polystyrene tube for estimation of Me[203Hg] content. One half of the right kidney was reserved for estimation of Me[203Hg] content while the other half placed in fixative (40% formaldehyde, 50% glutaraldehyde in 96.7 mM NaH2PO4 and 67.5 mM NaOH). The liver was excised, weighed, and a 1-g section was collected for determination of Me[203Hg] content. Lastly, the brain was removed, weighed, and placed in a vial for determination of Me[203Hg] content.

Urine and feces were collected every 24 hr following initial injection of MeHg. At each collection time, the volume of urine was noted and a 1ml sample was weighed and placed in a polystyrene tube for estimation of Me[203Hg] content. All of the feces excreted by each animal during each 24-hr period were counted to determine accurately total fecal content of Me[203Hg]. The Me[203Hg] in each sample was measured by counting in a Wallac Wizard 3 automatic gamma counter (PerkinElmer).

Histological Preparation of Tissues

Renal tissue from each rat was fixed in 40% formaldehyde, 50% glutaraldehyde in 96.7 mM NaH2PO4 and 67.5 mM NaOH for 48 hr at 4°C. Following fixation, kidneys were washed twice with normal saline and placed in 70% ethanol. Tissues were processed in a Tissue-Tek VIP processor using the following sequence: 95% ethanol for 30 min (twice); 100% ethanol for 30 min (twice); 100% xylene (twice). Tissue was subsequently embedded in POLY/Fin paraffin (Fisher) and 5 μm sections were cut using a Leitz 1512 microtome and mounted on glass slides. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) and viewed utilizing an Olympus IX70 microscope. The diameters of all glomeruli and proximal tubules within 4 randomly selected 400x microscopic fields were measured using an eyepiece reticle calibrated with a stage micrometer. Values are expressed as mean ± SE.

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA (Figures 1-5, Tables 3 & 4) or an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test (Figures 6 & 7, Table 2) to assess differences among means. A p-value of <0.05 was selected a priori to represent statistical significance. Each group of animals contained 3-5 rats. All data are expressed as mean ± SE.

Figure 1.

Amount of MeHg (nmol/g) in total renal mass of control and NPX rats after one, two, and three days of exposure to 5 mg/kg MeHg, containing 1 μCi Me[203Hg] per rat. Data represent mean ± SE of 3-5 rats. * Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for the same time period. + Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for 1 day. ◆ Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for 1 day and 2 days.

Figure 5.

Amount of MeHg (nmol/g) in brain of control and NPX rats after one, two, and three days of exposure to 5 mg/kg MeHg, containing 1 μCi Me[203Hg] per rat. Data represent mean ± SE of 3-5 rats. * Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for the same time period. + Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for 1 day. ◆ Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for 1 day and 2 days.

Table 3.

Plasma creatinine (mg/dl) in control and NPX rats.

| No Treatment | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.2158 ± 0.1 | 0.7298 ± 0.2b | 0.9438 ± 0.3b | 0.6741 ± 0.1b |

| NPX | 1.0343 ± 0.1a | 0.7765 ± 0.1b | 1.7974 ± 0.8a,b | 1.6037 ± 0.4a,b |

Significantly different (p < 0.05) from corresponding group of control rats.

Significantly different (p < 0.05) from corresponding group of un-treated rats.

Table 4.

Volume of urine (ml) excreted in each 24-hr period

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 12.67 ± 0.7 ml | 18.00 ± 4.2 mlb | 27.67 ± 3.2 mlb |

| NPX | 14.00 ± 0.8 ml | 30.50 ± 7.4 mla | 36.00 ± 11.3 mlb |

Significantly different (p < 0.05) from corresponding group of control rats.

Significantly different (p < 0.05) from corresponding group of un-treated rats.

Figure 6.

Total amount of MeHg (nmol/ml) in urine of control and NPX rats after one (A), two (B), and three (C) days of exposure to 5 mg/kg MeHg, containing 1 μCi Me[203Hg] per rat. Data represent mean ± SE of 3-5 rats. * Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for the same time period.

Figure 7.

Total amount of MeHg (nmol) in feces of control and NPX rats after one (A), two (B), and three (C) days of exposure to 5 mg/kg MeHg, containing 1 μCi Me[203Hg] per rat. Data represent mean ± SE of 3-5 rats. * Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for the same time period.

Table 2.

Tubular and glomerular diameter (μm)

| Tubular Diameter (μm) | Glomerular Diameter (μm) | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 42.01 ± 1.8 | 120.8 ± 2.5 |

| NPX | 58.95 ± 1.4a | 132.0 ± 5.8a |

Significantly different (p < 0.05) from corresponding group of control rats.

Results

Histological and Functional Analyses of Kidneys

Sections of kidneys from control and NPX rats were preserved for analyses of tubular and glomerular size. When the diameters (μm) of proximal tubules were determined (Table 2), tubules from NPX rats were found to be approximately 50% larger than controls. Measurements of glomerular diameter (μm) (Table 2) indicate that glomeruli from NPX rats are approximately 10% larger than controls. Treatment with MeHg did not markedly alter mean diameter of glomeruli and tubules.

Table 3 shows plasma creatinine (mg/dl) levels for each group of rats. Plasma levels of creatinine in control rats not exposed to MeHg were similar to those published previously (Bridges et al. 2014; Oliveira et al. 2016). Creatinine levels in controls rose significantly after one and two days of exposure to MeHg (Groups 1 and 3, respectively). Interestingly, on the third day after exposure (Group 5), levels of plasma creatinine decreased and were similar to concentrations after one day of exposure (Group 1). In unexposed NPX rats, plasma creatinine was 5-fold greater than corresponding controls. Plasma creatinine levels in NPX animals did not significantly alter after one day of exposure to MeHg (Group 2) but increased nearly 2-fold after two days treatment (Group 4). Levels of plasma creatinine in NPX rats after three days of exposure (Group 6) were not markedly different from amounts after two days exposure.

Renal Burden of Mercury

It should be noted that although this investigation refers to accumulation and disposition of MeHg, the exact species of Hg present within the tissues was not determined. For the sake of simplicity, accumulated Hg is referred to as MeHg since animals were exposed to this form of metal. Yet, it is important to note that MeHg within biological systems may be biotransformed to inorganic forms of Hg (Norseth and Clarkson 1970a; 1970b).

The amount of MeHg (nmol/g) detected in the total renal mass of control rats after 1, 2, and 3 days of exposure (Groups 1, 3, and 5, respectively) was significantly higher than in remnant kidney of corresponding NPX rats (Groups 2, 4, and 6, respectively) (Figure 1). In addition, the renal burden of MeHg in control and NPX rats was significantly elevated after exposure to each dose of MeHg.

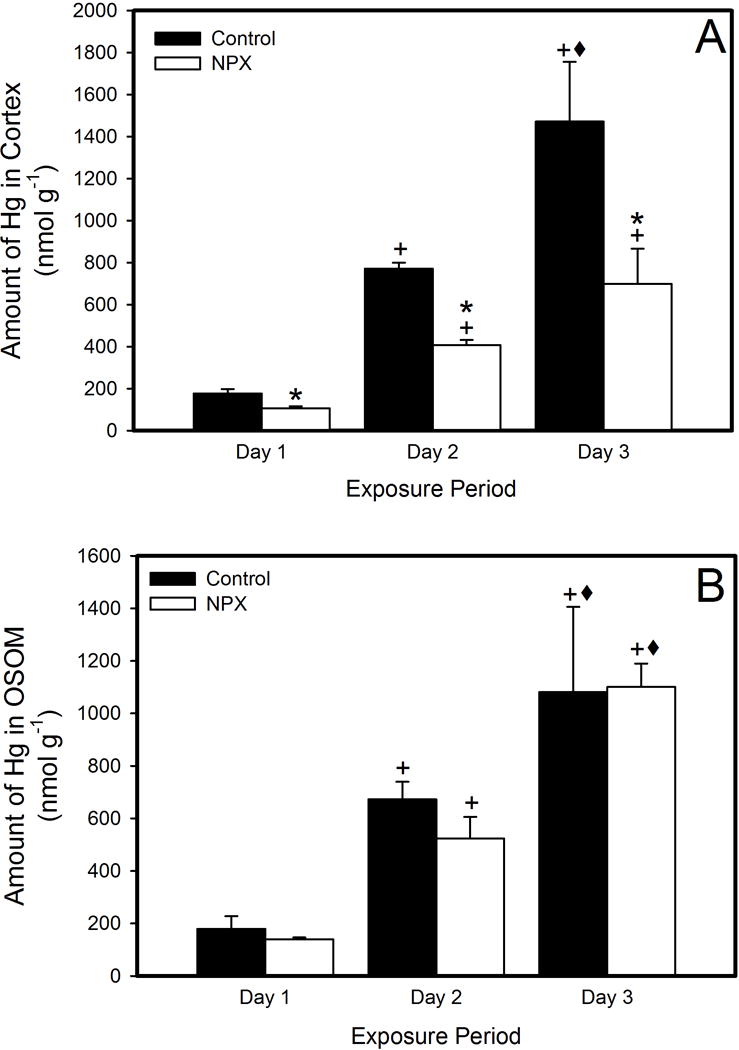

Figure 2 shows MeHg accumulation (nmol/g) in cortex (A) and OSOM (B) of left kidneys from control and NPX animals. The accumulation of MeHg within the renal cortex of controls (Groups 1, 3, and 5) was significantly greater than in NPX animals at every time period (Groups 2, 4, and 6). In both, control and NPX rats, the cortical burden of MeHg rose significantly over the 3-day exposure period. In contrast, accumulation of MeHg in OSOM was similar between control and NPX animals, although accumulation was elevated after each day of exposure. Interestingly, while the amount of accumulation of MeHg in the OSOM and cortex of control rats was similar, the quantity of MeHg accumulation in OSOM of NPX rats was higher than in cortex of corresponding NPX rats.

Figure 2.

Amount of MeHg (nmol/g) in cortex (A) and outer stripe of outer medulla (OSOM, B) of control and NPX rats after one, two, and three days of exposure to 5 mg/kg MeHg, containing 1 μCi Me[203Hg] per rat. Data represent mean ± SE of 3-5 rats. * Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for the same time period. + Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for 1 day. ◆ Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for 1 day and 2 days.

Accumulation of Mercury in Blood, Liver, and Brain

The amount of MeHg detected in blood (nmol/g body weight) was significantly greater in controls (Groups 1, 3, and 5) than corresponding NPX rats (Groups 2, 4, and 6) at each time point measured (Figure 3). In each group of rats, the amount of MeHg in blood increased significantly over the 3 days of exposure.

Figure 3.

Amount of MeHg (nmol/g body weight) in blood of control and NPX rats after one, two, and three days of exposure to 5 mg/kg MeHg, containing 1 μCi Me[203Hg] per rat. Data represent mean ± SE of 3-5 rats. * Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for the same time period. + Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for 1 day. ◆ Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for 1 day and 2 days.

The hepatic burden of MeHg (nmol/g) in controls (Groups 1, 3, and 5) was not significantly different from NPX (Groups 2, 4, and 6) at any time point (Figure 4). The accumulation of MeHg within liver of control and NPX rats rose over the course of the 3-day exposure. The accumulation of MeHg (nmol/g) in brains of controls (Groups 1, 3, and 5) was not markedly different NPX animals (Groups 2, 4, and 6) (Figure 5). The MeHg levels in brains of control and NPX rats increased significantly over the course of the 3-day exposure.

Figure 4.

Amount of MeHg (nmol/g) in liver of control and NPX rats after one, two, and three days of exposure to 5 mg/kg MeHg, containing 1 μCi Me[203Hg] per rat. Data represent mean ± SE of 3-5 rats. * Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for the same time period. + Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for 1 day. ◆ Significantly different (p < 0.05) from rats exposed to MeHg for 1 day and 2 days.

Urinary and Fecal Excretion of Mercury

The total volume of urine collected during each 24-hr period is presented in Table 4. The total amount of Hg excreted in urine (nmol/ml) of controls (Group 1) was not significantly different than corresponding NPX rats (Group 2) after 1 day exposure (Figure 6A). Interestingly after 2 days of treatment with MeHg (Figure 6B), total urinary excretion of MeHg was significantly higher in controls (Group 3) than NPX (Group 4). Following 3 days of exposure (Figure 6C), total urinary excretion of MeHg was similar between control (Group 5) and NPX rats (Group 6).

When MeHg was measured in feces (nmol), the total amount of MeHg detected in feces of controls exposed for 1 day (Group 1) was significantly less than in NPX rats (Group 2) (Figure 7A). Interestingly, after 2 days of exposure, fecal excretion of MeHg was similar between control (Group 3) and NPX animals (Group 4) (Figure 7B). After 3 days treatment with MeHg, total fecal excretion was significantly reduced in NPX (Group 6) compared to control (Group 5) (Figure 7C).

Discussion

Understanding the effects of exposure to heavy metals such as Hg in patients with CKD is important to patient health. Indeed, exposure to low-levels of Hg, lead (Pb), and/or cadmium (Cd) was shown to reduce glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (Afrifa et al. 2017; Barregard et al. 2014; Buser et al. 2016; Kim and Lee 2012; Nuyts et al. 1995; Brewster 2006; Brewster and Perazella 2004) and enhance the progression of disease in CKD patients (Sommar et al. 2013; Tsai et al 2017a; 2017b).

The current study utilized a 75% NPX rat model to mimic a patient in the latter stages of CKD. Measurements of plasma creatinine in these rats suggested that glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of NPX rats was reduced significantly compared with controls. This decrease may be attributed to sclerotic change in the kidney leading to a diminished overall renal plasma flow to that kidney. Indeed, a large area of sclerotic tissue was present in the region of the kidney affected by ligation of the posterior branch of the renal artery (data not shown). In addition, glomerular and tubular diameters were significantly greater in remnant kidneys of NPX rats than corresponding controls suggesting that the remaining functional nephrons in the NPX rats had undergone compensatory hypertrophy in an attempt to compensate for loss of function. Single nephron GFR (SNGFR) might also be increased in these hypertrophied nephrons (Fine et al 1992).

The renal burden of MeHg (nmol/g) in controls (Groups 1, 3, and 5) was significantly higher than in NPX animals (Groups 2, 4, and 6) at every time point measured. Less accumulation of MeHg in the remnant renal mass of NPX rats might be attributed to diminished renal plasma flow, reduced GFR, and a consequent decrease in delivery of MeHg to renal tubules. Although it was not possible to measure uptake of MeHg at the site of individual tubules, it is postulated that hypertrophied tubules in NPX rats may exhibit an enhanced ability to take up MeHg compared with normal nephron tubules. At the level of the individual tubule, hypertrophied tubules may be exposed to higher quantities of MeHg associated with an increased SNGFR. Further, hypertrophied tubules may accumulate more MeHg due to enhanced expression of transport proteins and greater transport capacity for metal. Previously Bridges et al (2016) reported that individual hypertrophied proximal tubules accumulate greater amounts of Hg than normal proximal tubules. Despite the potential for elevated accumulation in hypertrophied tubules, overall renal plasma flow to kidneys is often reduced as CKD progresses (Thompson et al. 2014). A reduction in renal plasma flow may decrease the overall delivery of MeHg to the kidney. The current findings showing less accumulation of MeHg in kidneys of NPX animals are in agreement with this postulation.

Renal accumulation of mercuric ions was shown to occur within the first hr of exposure (Zalups 1993). The present data also suggest that renal accumulation of MeHg is rapid. Further, it appears that renal accumulation of MeHg continues over the three-day exposure period. This accumulation might be associated with binding of mercuric ions to intracellular thiols after uptake into cells. Retention of mercuric ions within renal tubular cells may lead to injury and acute tubular necrosis. Interestingly, treatment of animals with MeHg over the course of three days led to a significant rise in urine volume. Indeed, renal tubular injury is characterized by the presence of polyuria. Current measurements of plasma creatinine support the observations that renal accumulation of MeHg leads to tubular injury. After one day treatment, levels of plasma creatinine in controls (Group 1) increased 3.4-fold while there was no significant change in corresponding NPX animals (Group 2). It is important to note that the accumulation of MeHg was higher in control kidneys, suggesting that during the initial period of exposure, control kidneys may be at greater risk of MeHg-induced intoxication. After two days treatment with MeHg, plasma creatinine in controls (Group 3) was elevated by only 30%, suggesting that the initial period of exposure led to the most significant injury in these animals. In corresponding NPX rats (Group 4), two days of exposure led to an 80% increase in plasma creatinine, suggesting that as MeHg accumulation in the remnant kidney rises, the nephrons become more susceptible to MeHg-induced renal injury. The delay in tubular injury may also be related to the concomitant reduction in renal blood flow to NPX kidneys.

The accumulation of MeHg in cortex and OSOM was also determined. The accumulation of MeHg in the renal control cortex (Groups 1, 3, and 5) was significantly greater than in NPX (Groups 2, 4, and 6) on each day of exposure. In contrast, accumulation of MeHg in OSOM of controls was similar to NPX kidneys on each day of treatment. Differences in the pattern of accumulation may be related to location and function of transporters involved in uptake of mercuric ions. It is important to note that the segments of the early proximal tubule (S1 and S2) are located within the cortex. These segments display a high capacity for uptake of various ions, amino acids, and other substances, including MeHg. Previous reports indicated that MeHg forms a complex with the amino acid, cysteine (i.e., MeHg-Cys), within biological systems. It was suggested that MeHg-Cys is similar in size and shape to the amino acid methionine and that MeHg-Cys may act as a mimic of methionine at the site of amino acid transporters, similar to those in the proximal tubules (Aschner and Clarkson 1989; Aschner et al. 1990; Ballatori 2002; Bridges and Zalups 2005). It is conceivable that MeHg is presented to proximal tubules as a MeHg-Cys complex, which might be taken up readily by proximal tubular cells. Further, evidence indicates that the capacity for uptake of MeHg is greatest in the S1 and S2 segments of the proximal tubule. The capacity and/or affinity of S3 tubules in the OSOM may be lower than those in the cortex, indicating that these carriers may be saturated at low concentrations of MeHg. This phenomenon might explain why accumulation of MeHg in OSOM of control and NPX rats is similar.

The hematologic burden of MeHg in controls (Groups 1, 3, and 5) increased significantly over the course of the three-day exposure to MeHg. Surprisingly, the amount of MeHg in blood of NPX animals (Groups 2, 4, and 6) was significantly lower. This finding was unexpected considering that renal uptake of MeHg was greater in control than NPX and uptake of MeHg in other organs was similar between control and NPX. This observation can not be explained completely by our present data; however, data suggest that in NPX rats, deposition of MeHg may occur in areas of the body that were not measured in the current study.

As shown previously accumulation of MeHg in liver and brain of control animals (Groups 1, 3, and 5) was similar to that of NPX (Groups 2, 4, and 6). This finding suggests that renal insufficiency does not exert a significant effect on delivery of toxicants to liver and brain. However, it is important to note that both, control and NPX animals continued to excrete MeHg via feces and urine. Alterations in the excretory ability of these animals might lead to subsequent alterations in delivery to and handling by the liver and brain.

Fecal excretion of MeHg in control and NPX rats increased significantly over the course of the 3-day treatment period despite a lack of accumulation of mercuric ions in liver. It is postulated that this excretion may occur either through intestinal secretion or hepatobiliary elimination. Zalups (1998) showed that mercuric ions may be secreted by intestinal enterocytes into the lumen of the intestine for eventual elimination in feces; therefore, intestinal secretion may be one route of elimination. In addition, MeHg entering hepatocytes may be transported efficiently into bile via the multidrug resistance transporter 2 (MRP2) such that accumulation of mercuric ions within hepatocytes is minimal. MRP2 was found to mediate the transport of mercuric species (Zalups and Bridges 2009) and thus, may play a role in the hepatobiliary elimination of mercuric ions. Similarly, urinary excretion of MeHg rose over the first two days of the exposure period. A lack of elevated urinary excretion on Day 3 may be attributed to enhanced retention of MeHg within the kidney.

In summary, the current study provides data suggesting that renal insufficiency exerts significant effects on renal and hematologic handling of MeHg. Further, data confirm that the accumulation of mercuric ions in the kidney is rapid. In addition, renal accumulation and injury continues with prolonged exposure to mercuric species and urinary excretion is unable to effectively remove mercuric ions from the kidney when exposure to MeHg occurs over multiple days. Based upon our plasma creatinine data, it is proposed that normal kidneys are more susceptible to MeHg-induced intoxication during the initial period of exposure while animals, and possibly humans, with renal insufficiency appear to be more susceptible to MeHg-induced intoxication after multiple days of treatment with MeHg. Overall, these findings provide important insight into the handling of toxicants by animals with reduced renal mass and may contribute to the understanding of how patients with CKD handle toxicants and other xenobiotics.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH/NIEHS (ES019991) and Navicent Health Foundation.

References

- Afrifa J, Essien-Baidoo S, Ephraim RKD, Nkrumah D, Dankyira DO. Reduced egfr, elevated urine protein and low level of personal protective equipment compliance among artisanal small scale gold miners at Bibiani-Ghana: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:601. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4517-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschner M, Clarkson TW. Methyl mercury uptake across bovine brain capillary endothelial cells in vitro: The role of amino acids. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1989;64:293–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1989.tb00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschner M, Eberle NB, Goderie S, Kimelberg HK. Methylmercury uptake in rat primary astrocyte cultures: The role of the neutral amino acid transport system. Brain Res. 1990;521:221–228. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91546-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- P. H. S. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, editor. ATSDR, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for Mercury. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ballatori N. Transport of toxic metals by molecular mimicry. Environ Health Persp. 2002;110(Suppl 5):689–694. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barregard L, Bergstrom G, Fagerberg B. Cadmium, type 2 diabetes, and kidney damage in a cohort of middle-aged women. Environ Res. 2014;135:311–316. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanger M, Westin A, Barfuss DW. Some health physics aspects of working with 203Hg in university research. Health Phys. 2001;80:S28–S30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branco V, Caito S, Farina M, Teixeira da Rocha J, Aschner M, Carvalho C. Biomarkers of mercury toxicity: Past, present and future trends. J Toxicol Environ Health B. 2017;20:119–154. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2017.1289834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster UC. Chronic kidney disease from environmental and occupational toxins. Conn Med. 2006;70:229–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster UC, Perazella MA. A review of chronic lead intoxication: An unrecognized cause of chronic kidney disease. Am J Med Sci. 2004;327:341–347. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200406000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CC, Barfuss DW, Joshee L, Zalups RK. Compensatory renal hypertrophy and the uptake of cysteine S-conjugates of Hg2+ in isolated S2 proximal tubular segments. Toxicol Sci. 2016;154:278–288. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CC, Bauch C, Verrey F, Zalups RK. Mercuric conjugates of cysteine are transported by the amino acid transporter system b(0,+): Implications of molecular mimicry. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:663–673. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000113553.62380.F5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CC, Joshee L, Zalups RK. Effect of DMPS and DMSA on the placental and fetal disposition of methylmercury. Placenta. 2009;30:800–805. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CC, Joshee L, Zalups RK. Aging and the disposition and toxicity of mercury in rats. Exp Gerontol. 2014;53:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CC, Zalups RK. Molecular and ionic mimicry and the transport of toxic metals. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;204:274–308. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges CC, Zalups RK. The aging kidney and the nephrotoxic effects of mercury. J Toxicol Environ Health B. 2017;20:55–80. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2016.1243501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buser MC, Ingber SZ, Raines N, Fowler DA, Scinicariello F. Urinary and blood cadmium and lead and kidney function: NHANES 2007-2012. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2016;219:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro MFH, Grotto D, Barbosa F., Jr Inorganic and methylmercury levels in plasma are differentially associated with age, gender, and oxidative stress markers in a population exposed to mercury through fish consumption. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2014;77:69–79. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2014.865584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C Department of Health and Human Services, editor. CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Kidney Disease Fact Sheet. National Center for Health Statistics; Atlanta, GA: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FDA. Eating Fish: What Pregnant Women and Parents Should Know. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000515224.05161.d6. [cited 11-29-17 2017] Available from https://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm393070.htm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine LG, Norman JT, Kujubu DA, Knecht A. Renal hypertrophy. In: Seldin DW, Giebisch G, editors. The Kidney: Physiology and Pathophysiology. New York: Raven Press; 1992. pp. 3113–3133. [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1151–1210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Lee BK. Associations of blood lead, cadmium, and mercury with estimated glomerular filtration rate in the Korean general population: Analysis of 2008-2010 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. Environ Res. 2012;118:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lash LH, Hueni SE, Putt DA, Zalups RK. Role of organic anion and amino acid carriers in transport of inorganic mercury in rat renal basolateral membrane vesicles: influence of compensatory renal growth. Toxicol Sci. 2005;88:630–644. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lash LH, Putt DA, Zalups RK. Influence of exogenous thiols on inorganic mercury-induced injury in renal proximal and distal tubular cells from normal and uninephrectomized rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:492–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HB, Blaufox MD. Blood volume in the rat. J Nucl Med. 1985;26:72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, 3rd, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Willey JZ, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee Heart disease and stroke statistics–2015 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–2e322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norseth T, Clarkson TW. Biotransformation of methylmercury salts in the rat studied by specific determination of inorganic mercury. Biochem Pharmacol. 1970a;19:2775–2783. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(70)90104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norseth T, Clarkson TW. Studies on the biotransformation of 203Hg-labeled methyl mercury chloride in rats. Arch Environ Health. 1970b;21:717–727. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1970.10667325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuyts GD, Van Vlem E, Thys J, De Leersnijder D, D’Haese PC, Elseviers MM, De Broe ME. New occupational risk factors for chronic renal failure. Lancet. 1995;346:7–11. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92648-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira CS, Joshee L, Zalups RK, Bridges CC. Compensatory renal hypertrophy and the handling of an acute nephrotoxicant in a model of aging. Exp Gerontol. 2016;75:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez H, Sullivan EC, Michael K, Harris R. Fish consumption and advisory awareness among the Philadelphia Asian community: A pilot study. J Environ Health. 2012;74:24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee CM, Kovesdy CP. Spotlight on CKD deaths—increasing mortality worldwide. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11:199. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouleau C, Block M. Fast and high yield synthesisi of radioactive CH3203Hg(II) Appl Organomet Chem. 1997;11:751–753. [Google Scholar]

- Sommar JN, Svensson MK, Bjor BM, Elmstahl SI, Hallmans G, Lundh T, Schon SM, Skerfving S, Bergdahl IA. End-stage renal disease and low level exposure to lead, cadmium and mercury: A population-based, prospective nested case-referent study in Sweden. Environ Health. 2013;12:9. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-12-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DL, Williamson PR. Mercury contamination in Southern New England coastal fisheries and dietary habits of recreational anglers and their families: Implications to human health and issuance of consumption advisories. Mar Pollut Bull. 2017;114:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.08.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A, Lawrence J, Stockbridge N. GFR decline as an end point in trials of CKD: a viewpoint from the FDA. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:836–837. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CC, Wu CL, Kor CT, Lian IB, Chang CH, Chang TH, Chang CC, Chiu PF. Prospective associations between environmental heavy metal exposure and renal outcomes in adults with chronic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2017a doi: 10.1111/nep.13089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai TL, Kuo CC, Pan WH, Chung YT, Chen CY, Wu TN, Wang SL. The decline in kidney function with chromium exposure is exacerbated with co-exposure to lead and cadmium. Kidney Int. 2017b;92:710–720. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya A, Hinners TA, Burbacher TM, Faustman EM, Marien K. Mercury exposure from fish consumption within the Japanese and Korean communities. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2008;71:1019–1031. doi: 10.1080/01932690801934612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S, Brown G, Chen J, Meals K, Thornton C, Brewer S, Cizdziel JV, Willett KL. Mercury concentrations in fish from three major lakes in north Mississippi: Spatial and temporal differences and human health risk assessment. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2016;79:894–904. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2016.1194792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalups RK. Early aspects of the intrarenal distribution of mercury after the intravenous administration of mercuric chloride. Toxicology. 1993;79:215–228. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(93)90213-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalups RK. Intestinal handling of mercury in the rat: Implications of intestinal secretion of inorganic mercury following biliary ligation or cannulation. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1998;53:615–636. doi: 10.1080/009841098159079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalups RK, Bridges CC. MRP2 involvement in renal proximal tubular elimination of methylmercury mediated by DMPS or DMSA. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;235:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalups RK, Lash LH. Effects of uninephrectomy and mercuric chloride on renal glutathione homeostasis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;254:962–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]