Abstract

Crown gall disease, caused by the soil bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens, results in significant economic losses in perennial crops worldwide. A. tumefaciens is one of the few organisms with a well characterized horizontal gene transfer system, possessing a suite of oncogenes that, when integrated into the plant genome, orchestrate de novo auxin and cytokinin biosynthesis to generate tumors. Specifically, the iaaM and ipt oncogenes, which show ≈90% DNA sequence identity across studied A. tumefaciens strains, are required for tumor formation. By expressing two self-complementary RNA constructions designed to initiate RNA interference (RNAi) of iaaM and ipt, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana and Lycopersicon esculentum plants that are highly resistant to crown gall disease development. In in vitro root inoculation bioassays with two biovar I strains of A. tumefaciens, transgenic Arabidopsis lines averaged 0.0–1.5% tumorigenesis, whereas wild-type controls averaged 97.5% tumorigenesis. Similarly, several transformed tomato lines that were challenged by stem inoculation with three biovar I strains, one biovar II strain, and one biovar III strain of A. tumefaciens displayed between 0.0% and 24.2% tumorigenesis, whereas controls averaged 100% tumorigenesis. This mechanism of resistance, which is based on mRNA sequence homology rather than the highly specific receptor–ligand binding interactions characteristic of traditional plant resistance genes, should be highly durable. If successful and durable under field conditions, RNAi-mediated oncogene silencing may find broad applicability in the improvement of tree crop and ornamental rootstocks.

Crown gall disease is a chronic and resurgent disease problem that affects many perennial fruit, nut, and ornamental crops. Growers and nursery industries suffer significant annual losses worldwide to crown gall disease in the form of unsalable nursery stock, lowered productivity from galled trees, and increased susceptibility of infected plants to pathogens and environmental stress (1). Although extensive research efforts have studied the epidemiology of crown gall throughout this century, prevention strategies have, for the most part, remained focused on phytosanitation, such as the “careful cultural methods,” “strict inspection of nursery stock,” and “abandonment of infected soils” prescribed by Smith in 1911 (2). More recently, the biocontrol strain Agrobacterium radiobacter K84 has been widely used for crown gall disease management; however, effective control is limited to a subset of all virulent Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains (3). Traditional breeding strategies for crown gall disease resistance are possible in some perennial crop species where resistant germplasm is present, but breeding requires decades to achieve resistance in commercially available perennial crop rootstocks (1). Overall, the prevalence of crown gall disease in the field is a testament to the limited success of traditional control strategies.

Although control of crown gall disease has proved elusive, the molecular biology and genetics of A. tumefaciens–plant interactions has become well characterized, in part because of the pivotal role of Agrobacterium as a vector for the introduction of foreign genes into plants (4). A. tumefaciens pathogenesis can be considered a two-stage process: (i) bacterial responses facilitating horizontal gene transfer and integration into the plant genome (transformation) and (ii) postintegration events occurring in planta (tumorigenesis). A. tumefaciens transformation occurs at plant wound sites, where phenolic compounds released by wounded plant cells trigger induction of a set of virulence (vir) genes, one of which is responsible for the cleavage of a discrete single strand of DNA (T-DNA) from the large tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid. The T-DNA is transferred from Agrobacterium into the plant cell through a complex vir gene-encoded protein and nucleic acid translocator, which is homologous to a plasmid conjugation pilus (5). Inside the plant cell, the T-DNA is localized to the nucleus where it becomes integrated into the genome (6). Despite their prokaryotic origin, genes in the T-DNA are expressed in the plant's nucleus and produce proteins that initiate tumorigenesis and create an environment suitable for A. tumefaciens growth and interbacterial Ti plasmid conjugation (7).

Two main classes of T-DNA genes are expressed in infected plant cells: opine synthesis genes and oncogenes. Opine synthesis genes direct the production of novel metabolites termed opines, most of which are simple derivatives of amino acids conjugated with sugars or diketo acids (8). Opines can serve as the sole carbon and/or nitrogen source for the infecting strain of A. tumefaciens. Expression of oncogenes causes overproduction of the plant hormones auxin and cytokinin and may alter phytohormone sensitivity, resulting in the initiation of uncontrolled cell growth/division and gall formation (7). The oncogene region of the T-DNA has classically been referred to as “core sequence” because the region shares high DNA sequence homology across all virulent A. tumefaciens strains (9, 10).

We have developed a crown gall disease control strategy that targets the process of gall formation (tumorigenesis) in planta by initiating RNA interference (RNAi) of the iaaM and ipt oncogenes. The iaaM gene codes for a tryptophan monooxygenase that converts tryptophan to the auxin precursor indoleacetamide (11). The ipt gene product catalyzes the condensation of AMP and isopentenyl pyrophosphate to form the cytokinin zeatin (12). Expression of both of these oncogenes is required for wild-type tumor formation (13). RNAi is a form of homology-dependent gene silencing common to fungi, animals, and plants (14). Although some specifics of the silencing mechanism may differ between kingdoms, double-stranded RNA seems to be a universal initiator of RNAi (14). In plants, expression of self-complementary RNAs from introduced transgene constructions has proved a rapid and consistent initiator of RNAi for several genes in Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabaccum (tobacco) (15–17). We transformed A. thaliana and Lycopersicon esculentum (tomato) with a transgene construction designed to generate self-complementary iaaM and ipt transcripts. Resultant transgenic lines retained susceptibility to Agrobacterium transformation but were in some cases highly refractory to tumorigenesis, providing functional resistance to crown gall disease.

Materials and Methods

Oncogene Sequence Analysis.

The MEGALIGN multiple sequence alignment program (DNAstar, Madison, WI) was used to align the iaaM and ipt DNA sequences from biovar I and biovar II A. tumefaciens present in GenBank (data not shown). Based on cross-strain oncogene sequence homology (≈90%), we designed two sets of PCR primers with minimal degeneracy for the amplification of iaaM and ipt from other A. tumefaciens strains. We PCR amplified and cloned an internal 2,224-bp fragment of the iaaM gene from the virulent biovar 1 A. tumefaciens strain 20W-5A, which had previously been isolated from a Juglans regia (English walnut) crown gall. Similarly, a fragment corresponding to the first 627 bp of the ipt coding sequence was cloned from A. tumefaciens 20W-5A.

Binary Vector Construction and Plant Transformation.

A self-complementary ipt construct was created by fusing one sense copy of ipt-20W-5A bp 45–627 to an identical fragment in the antisense orientation. The two complementary ipt fragments were separated by a 1,000-bp region of noncoding linker DNA derived from the cloning vector. A self-complementary iaaM construction was generated by fusing one antisense copy of iaaM-20W-5A bp 1,274–2,224 to the 5′ end of a full-length sense iaaM-20W-5A fragment. This created an inverted repeat of a 950-bp region corresponding to the 3′ end of iaaM, interrupted by a noncomplementary linker region corresponding to bp 1–1,273 of iaaM. The self-complementary constructions were individually ligated into a plant expression vector containing the 35S cauliflower mosaic virus promoter and the octopine synthase terminator. The resultant expression cassettes were then ligated into the binary vector pDU99.2215, which contains an nptII-selectable marker gene driven by the mannopine synthase promoter and a uidA (β-glucuronidase, GUS) scorable marker gene driven by the ubi3 promoter from potato. The resultant binary vector, pDE00.0201, was transformed into the disarmed A. tumefaciens strain EHA101 by electroporation (Fig. 1).

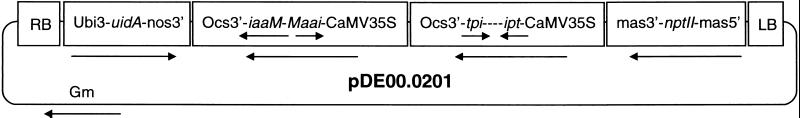

Figure 1.

The Agrobacterium binary vector pDE00.0201 for the expression of self-complementary iaaM and ipt oncogenes. This vector contains an nptII-selectable marker gene driven by the mannopine synthase 2′ promoter (mas5′), a uidA scorable marker gene driven by the ubi3 promoter (ubi3), and self-complementary iaaM and ipt genes driven by 35S cauliflower mosaic virus promoters. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription. LB and RB indicate the left and right T-DNA border sequences.

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of A. thaliana ecotype Wassilewskija was performed by the whole-plant infiltration method described by Bechtold et al. (18). Transformants were identified by selecting seed on half-strength Murashige–Skoog medium containing 75 mg/liter kanamycin. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of L. esculentum cultivar Moneymaker was performed as described by Fillatti et al. (18). Transformed shoots were selected on 2Z medium containing 50–100 mg/liter kanamycin (19).

Molecular Characterization of Transformants.

Southern hybridization of total genomic DNA and fluorimetric GUS analysis was performed essentially as described by Sambrook et al. and Jefferson, respectively (20, 21). Total leaf and stem RNA was isolated by using a Qiagen plant RNeasy kit. Isolated RNA was treated with RNase free DNase, and first-strand cDNA synthesis was primed with a poly T primer by using Stratagene's ProSTAR first-strand cDNA kit. First-strand synthesis reactions lacking reverse transcriptase were included as a control for DNA contamination.

For competitive PCR amplification of ipt cDNA, reactions included 25 pmol of each primer, 200 μM dNTPs, 1 × CLONTECH cDNA PCR reaction buffer, 1 × CLONTECH Advantage cDNA polymerase, and 0.005, 0.05, or 0.5 pg of serially diluted internal standard (22). Thirty thermocycles were performed with 94°C denaturation (30 s), 60°C annealing (1 min), and 68°C extension (2 min). Amplification of iaaM cDNA was as described above, except 0.002, 0.01, or 0.05 pg of internal standard was included and 32 thermocycles were performed with a 63°C annealing temperature. PCR products were electrophoresed through 1.6% agarose gels and analyzed by spot densitometry using an Alpha Innotech IS-1000 digital imaging system. Relative quantification of amplified cDNA bands was performed as described by Kermouni et al. (22).

Transformation and Tumorigenesis Bioassays.

Roots from Arabidopsis transformants were harvested from plants grown in culture and diced into ≈0.5-cm pieces. Four to five individual root pieces were gathered into a bundle and inoculated with a 2 × 109 CFU/ml suspension of the virulent A. tumefaciens strains A208 or 20W-5A to assay tumorigenesis or with the avirulent strain EHA101 containing the glufosinate resistance binary vector pMLBART to assay transformation efficiency (23, 24). In vitro culture of inoculated root bundles was performed essentially as described by Nam et al., with the exception of the use of cefotaxime (250 mg/liter) as a bacteriostatic agent (24). Tumorigenesis (A208, 20W-5A) or the formation of glufosinate-resistant calli (EHA101/pMLBART) was scored 5 weeks after inoculation. A minimum of 60 root bundle replicates was performed for tumorigenesis assays and a minimum of 30 replicates was performed for transformation assays.

The stem of tomato seedlings was inoculated with an 8 × 107 CFU/ml suspension of various A. tumefaciens (Table 1) or Agrobacterium rhizogenes strains. A syringe equipped with a 25-gauge needle was loaded with bacterial suspension, the needle was pushed through the stem, and a small droplet of suspension was extruded as the needle was pulled back through the stem. Tumorigenesis or rhizogenesis was scored 5 weeks after inoculation. A minimum of 12 seedlings was inoculated for each Agrobacterium strain (20W-5A, 15955, C58, 127A, CG49, and A4).

Table 1.

Genotypic properties of A. tumefaciens strains used in disease-challenge bioassays of transgenic plants

| Strain | Biovar | K84 sensitivity | Opine(s) produced | Homology to ipt, %† | Homology to iaaM, %† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20W-5A* | I | R | Mannopine/agropine | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 15955 | I | R | Octopine/mannopine/agrocinopine | 91.1 | 90.8 |

| A208 | I | S | Nopaline | 99.0 | 93.0 |

| C58 | I | S | Nopaline | 99.0 | 95.7 |

| 127A* | II | S | Nopaline | Unknown | Unknown |

| CG49 | III | R | Nopaline | Unknown | Unknown |

| EHA101 | I | R | — | — | — |

Strain isolated from walnut crown gall, not previously reported in the literature.

Homology to oncogene-silencing construct pDE00.0201.

Results and Discussion

Although A. tumefaciens is highly diverse in terms of genomic DNA structure and Ti plasmid organization, all virulent strains share highly homologous oncogenes that are required for tumor formation. We have attempted to exploit this commonality to generate resistance to crown gall tumorigenesis by targeting the iaaM and ipt oncogenes for RNAi-mediated gene silencing. Endogenous plant phytohormone biosynthesis pathways may contain reactions that are biochemically analogous to those catalyzed by iaaM and ipt, but no plant genes with significant sequence similarity to these oncogenes have ever been reported (25, 26). Thus, iaaM and ipt could be silenced in plant cells infected by A. tumefaciens without otherwise altering plant hormone metabolism. Using iaaM and ipt sequences cloned from the biovar I A. tumefaciens strain 20W-5A, we constructed two expression cassettes designed to generate self-complementary iaaM and ipt transcripts. These cassettes were cloned into an Agrobacterium binary vector, generating pDE00.0201 (Fig. 1). Tomato and Arabidopsis, two plants that are highly susceptible to crown gall disease, were transformed with pDE00.0201, and putative transformants were regenerated under kanamycin selection.

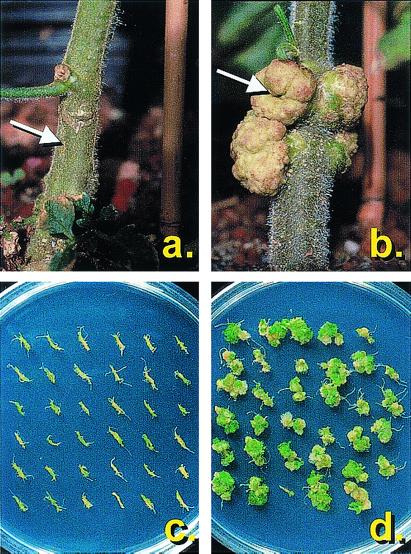

Plant transformation and transgene expression were confirmed by Southern hybridization of total genomic DNA, fluorimetric GUS analysis, and reverse transcriptase–PCR (data not shown). Transgenic plants were generally indistinguishable from the wild type in gross morphology and development. To identify putatively resistant individuals, several primary transformant lines were challenged with biovar I strains of A. tumefaciens in small-scale disease bioassays. Arabidopsis transformants were infected with A. tumefaciens A208 in in vitro root inoculation bioassays, and primary tomato transformants were stem inoculated with A. tumefaciens 20W-5A. Sixty percent (3 of 5) of tested tomato transformants and 50% (3 of 6) of tested Arabidopsis transformants displayed a complete abolition of tumorigenesis in these initial primary screens (Fig. 2). A high percentage of transformants displaying the silenced phenotype is characteristic of the expression of self-complementary RNA; however, it is interesting to note that two different RNA targets were simultaneously silenced with such high efficiency (15–17). No consistent tumor morphology phenotypes indicative of the silencing of a single oncogene were observed (e.g., rooty tumors, shooty tumors, attenuation; ref. 13).

Figure 2.

A. tumefaciens tumorigenesis on tomato and Arabidopsis. Transgenic (a) and wild-type (b) tomatoes were infected with A. tumefaciens 20W-5A by piercing the stem with a syringe and extruding a small amount of bacterial suspension into the wound. Tumorigenesis was scored 5 weeks after inoculation. Large tumors are evident at the inoculation site (marked with an arrow) on the wild-type plant but not the transgenic plant, indicating suppression of tumorigenesis. In the lower panels, in vitro grown roots were harvested from transgenic (c) and wild-type (d) Arabidopsis lines and inoculated with A. tumefaciens A208. Tumorigenesis was scored 5 weeks after inoculation. Large teratoma-type tumors are present on wild-type root bundles but not on transgenic root bundles, again indicating suppression of tumorigenesis.

Two putatively resistant tomato lines (01/1, 01/6) and two putatively resistant Arabidopsis lines (01/29, 01/33) were selected for large-scale disease screening with various biovar I, II, and III strains of A. tumefaciens (Table 1). Based on genomic Southern hybridization analysis, lines 01/6 and 01/29 have a single T-DNA insert, line 01/33 has two T-DNA inserts, and line 01/1 has three T-DNA inserts. Transgenic individuals selected from segregating T1 populations were used for large-scale screening to discern any phenotypic effects of hemizygosity vs. homozygosity of the transgene locus.

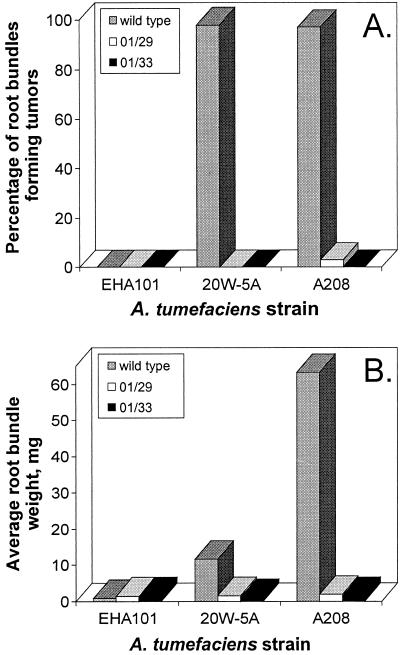

A minimum of 60 root bundles from the A. thaliana lines 01/29, 01/33, and wild type were separately inoculated with A. tumefaciens 20W-5A and A208. On average, 97.5% of wild-type root bundles generated tumors, whereas the two transgenic lines averaged 0.0% and 1.5% tumorigenesis (Fig. 3). Further, the average root bundle biomass from the wild-type root bundles infected with virulent A. tumefaciens was at least one order of magnitude greater than the mass of comparable root bundles from the transgenic 01/29 and 01/33 lines (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of tumor incidence (A) and biomass (B) in wild-type and transgenic Arabidopsis lines. (A) Summary of tumor incidence among 60 A. thaliana root bundles obtained from the wild-type or the transgenic lines 01/29 and 01/33 when inoculated with three different A. tumefaciens strains. The percentage of root bundles displaying tumors was assayed 5 weeks after inoculation. A208 and 20W-5A are virulent strains, and EHA101 is an avirulent strain that serves as a control. (B) Summary of the average root bundle weight from 60 root bundles 5 weeks after Agrobacterium inoculation. Any increase in average root bundle weight over the basal level of the EHA101 control is because of the accumulation of tumor biomass. The 01/29 and 01/33 lines are significantly different from the wild type in percentage tumor incidence and average root bundle biomass at the P = 0.05 level.

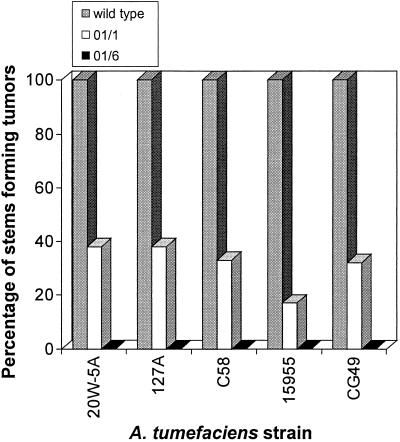

Analyzing tomato, a minimum of 12 seedlings from the lines 01/1, 01/6, and wild type were separately inoculated with the A. tumefaciens strains 20W-5A, 15955, C58, 127A, and CG49. For each inoculum, 100% of the wild-type seedlings developed undifferentiated tumors (Fig. 4). The 01/6 line was completely resistant to all tested A. tumefaciens strains, with 0% tumorigenesis (Fig. 4). The 01/6 line also displayed perfect cosegregation between GUS activity and resistance to disease development (52 of 52) and lack of GUS activity and disease susceptibility (14 of 14). Interestingly, 100% (66 of 66) of T1 01/1 individuals displayed GUS activity, but the line averaged 25.3% tumorigenesis. This line possesses three independent T-DNA insertion events, and it is possible that one or more of these inserts is capable of GUS expression but is incapable of initiating oncogene silencing. Alternatively, high transgene copy number in specific T1 individuals could lead to transcriptional gene silencing of the 35S cauliflower mosaic virus promoter that drives the silencing constructs (27). For both Arabidopsis and tomato, no phenotypic differences in resistance were apparent between hemizygous and homozygous individuals, which were subsequently identified by segregation analysis.

Figure 4.

Comparison of tumor incidence in wild-type and transgenic tomato lines. The figure shows an analysis of tumor incidence among wild-type and transgenic (01/1, 01/6) tomato seedlings inoculated with five different virulent A. tumefaciens strains (20W-5A, 127A, C58, 15955, and CG49). The percentage of stems displaying tumors was assayed 5 weeks after inoculation. The 01/1 and 01/6 lines are significantly different from the wild-type in percentage tumor incidence at the P = 0.05 level.

In a previous study, Nam et al. demonstrated that a relatively high percentage (0.7%) of randomly mutagenized A. thaliana lines display novel crown gall disease resistance phenotypes (28). Thus, it is possible, although unlikely given the resistance frequencies in primary transformants, that resistance to crown gall disease development is a result of random mutations inherent in the transformation system. If resistance were conferred by RNAi-mediated silencing of the iaaM and ipt genes, we would expect a highly specific block in tumorigenesis but no hindrance in the process of Agrobacterium transformation. Alternatively, all other forms of crown gall resistance characterized to date interfere in processes of transformation such as bacterial attachment, T-DNA transfer, or T-DNA integration (24, 28). To define the mechanism of resistance as a specific block in tumorigenesis, we inoculated tomato with A. rhizogenes A4, a hairy root-inducing species that possesses a transformation machinery that is functionally identical to A. tumefaciens but which does not require iaaM and ipt for rhizogenesis (29). Similarly, we performed A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis root bundles with the avirulent strain EHA101 containing an herbicide (glufosinate) resistance binary vector. Transformation was assayed by hairy root/tumor formation in tomato and by formation of glufosinate-resistant calli in Arabidopsis (24). As summarized in Table 2, transformation efficiencies were highly similar between wild-type and highly resistant plant lines, demonstrating that differences in transformation efficiency cannot account for resistance to disease development. Thus, the resistant transgenic lines possess a unique and highly specific uncoupling of the processes of transformation and tumorigenesis.

Table 2.

Comparison of Agrobacterium transformation efficiencies in wild-type and transgenic plants

| Plant-line | Tumorigenesis susceptibility | Inoculum | Transformation frequency, %† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis-wt | S | A. tumefaciens EHA101* | 73.3 (22/30) |

| Arabidopsis-01/33 | R | A. tumefaciens EHA101* | 87.5 (28/32) |

| Tomato-wt | S | A. rhizogenes A4 | 83.3 (10/12) |

| Tomato-01/6 | R | A. rhizogenes A4 | 76.9 (10/13) |

A. tumefaciens EHA101 containing a glufosinate resistance binary vector.

Transformation frequency determined by percentage of root bundles forming glufosinate-resistant calli (Arabidopsis) or percentage tumor/root formation at site of inoculation (tomato).

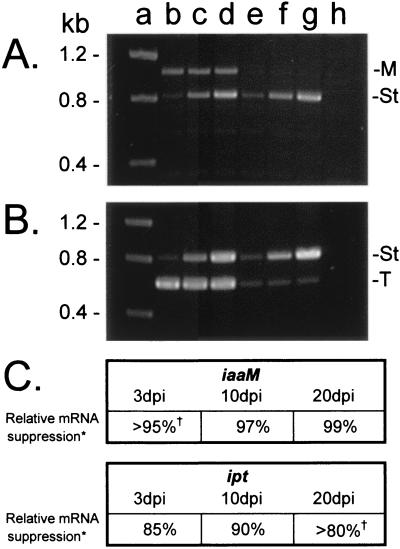

Because the process of transformation is unhindered in resistant plant lines, we would expect that individual cells from resistant plants are transformed by A. tumefaciens at a rate comparable with the wild type, but that these cells do not accumulate iaaM and ipt transcripts and therefore do not initiate tumorigenesis. To demonstrate directly a decrease in abundance of iaaM and ipt mRNAs in plant tissue inoculated with A. tumefaciens, we compared iaaM and ipt transcript abundance in 01/6 and wild-type tomato lines 3, 10, and 20 days after inoculation with A. tumefaciens 20W-5A. There are potentially three populations of iaaM/ipt mRNAs in infected plant tissue: self-complementary transcripts derived from the integrated oncogene-silencing constructs (present only in transgenic plants), transcripts produced in living A. tumefaciens by expression of the oncogene region of the Ti plasmid (produced at very low levels), and transcripts produced in planta from integrated virulent T-DNA (30). To isolate the last population, we performed first-strand cDNA synthesis using a poly T primer (elimination of nonpolyadenylated bacterial transcripts) and subsequently PCR-amplified regions of each oncogene that were not present in the oncogene-silencing constructions. To obtain a relative quantification of iaaM and ipt mRNA abundance, competitive PCR was performed on first-strand cDNA by using serial dilutions of a coamplified heterologous DNA internal standard (22). As shown in Fig. 5, the accumulation of both iaaM and ipt transcripts is significantly reduced in the transgenic line as compared with the wild type, demonstrating a positive correlation between oncogene mRNA abundance and disease susceptibility. This highly specific oncogene silencing efficiently targets mRNAs transcribed from both primarily nonintegrated [3 days postinoculation (dpi)] and integrated (10, 20 dpi) T-DNAs and is apparent even before phenotypic indications of resistance (≈15 dpi).

Figure 5.

Comparison of ipt and iaaM transcript abundance in wild-type and transgenic tomato by using competitive reverse transcriptase–PCR. Wild-type plants and plants from the crown gall-resistant transgenic line 01/6 were stem inoculated with A. tumefaciens 20W-5A, and RNA was extracted from inoculated stem tissue 3, 10, and 20 dpi. First-strand cDNA synthesis was primed with a polyT primer, and cDNA was subsequently PCR amplified in the presence of a known concentration of serially diluted competitive standard. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of 20 dpi iaaM competitive PCR reactions. Note the presence of an 815-bp internal standard amplification product (St) and a 1,035-bp iaaM cDNA amplification product (M). (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of 20 dpi ipt competitive PCR reactions. Note the presence of an 815-bp internal standard amplification product (St) and a 609-bp ipt cDNA amplification product (T). Lane markers apply to both panels. Lane a, molecular weight standard; lanes b–d, PCR amplification of wild-type cDNA in the presence of 0.002 pg (lane b), 0.01 pg (lane c), and 0.05 pg (lane d) of iaaM internal standard (A) or 0.005 pg (lane b), 0.05 pg (lane c), and 0.5 pg (lane d) of ipt internal standard (B). Lanes e–g, PCR amplification of cDNA from the transgenic line 01/6 in the presence of 0.002 pg (lane e), 0.01 pg (lane f), and 0.05 pg (lane g) of iaaM internal standard (A) or 0.005 pg (lane e), 0.05 pg (lane f), and 0.5 pg (lane g) of ipt internal standard (B). Lane H, PCR amplification of cDNA from a noninoculated control plant. (C) Comparison of oncogene mRNA abundance in wild-type and 01/6 plants at 3, 10, and 20 dpi. *, relative mRNA suppression refers to the abundance of 01/6 cDNA oncogene PCR amplification product as compared with the wild-type cDNA oncogene product (1 − [conc. of 01/6 product/conc. of wild-type product]). †, examples in which the 01/6 cDNA oncogene product was below the lower limit of detection are noted; the concentration of these products was recorded as less than the lowest concentration of internal standard.

Conclusions

Using an RNAi-mediated oncogene-silencing strategy, A. tumefaciens tumorigenesis was severely impaired in several transgenic lines of the highly susceptible model species Arabidopsis and tomato. The high level of cross-strain DNA sequence conservation in the iaaM and ipt oncogenes (≈90% identity in all sequenced genes) suggests that this strategy can provide broad spectrum resistance to crown gall tumorigenesis. Assuming that A. tumefaciens does not possess viral-type suppressors of gene silencing, we hypothesize that resistance could also be highly durable because specificity is mediated by RNA hybridization rather than protein–ligand binding. For many plant resistance gene systems, minor mutations in pathogen avirulence genes can disrupt the protein–protein interactions required to initiate a defense response (31). However, in an RNAi-mediated resistance system, mutation is unlikely to rapidly alter the target gene sequence to a level at which homology-dependent gene silencing no longer operates (≈70% homology; ref. 32).

In addition to their application in plant protection, oncogene-silenced plants may provide a unique opportunity to study the mechanism of posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. As in plants engineered with posttranscriptional gene silencing-mediated viral resistance, the mRNA species targeted for silencing is present only subsequent to pathogen infection. However, unlike a virus, A. tumefaciens integrates virulent DNA into the plant genome, and this integration event is unique in organization and copy number in every infected plant cell. Thus, at any A. tumefaciens infection site, there are potentially tens to hundreds of different T-DNA integration events, any one of which, if not silenced, could generate a crown gall. The fact that tumorigenesis is uniformly inhibited in transgenic lines suggests that the silencing of iaaM and ipt transcripts is independent of the structure, location, and copy number of the target locus in genomic DNA. Thus, our results suggest that the silencing locus alone, not a specific interaction between the silencing locus and the target locus, determines the efficiency of gene silencing.

Several factors lend this oncogene-silencing strategy to application in susceptible ornamental and horticultural plants. The resistance phenotype is generated with a single integrated copy of the silencing locus, eliminating the lengthy step of selecting homozygous progeny in slow-maturing perennials. Further, the prevalence of graft propagation allows transformation of rootstocks alone, providing resistance without altering the genetic composition of the harvested crop and without the possibility of undesired transgene flow through pollen. However, although oncogene-silenced plants are highly resistant to tumorigenesis, it should be noted that there is no evidence that they are deficient as carriers of rhizoplane populations of A. tumefaciens (33). As such, good nursery practices would need to be maintained in the cultivation of these plants to minimize the dissemination of large populations of virulent A. tumefaciens into growers' fields. Cocultivation of susceptible indicator plants with resistant plants in the nursery could provide a useful visual check of A. tumefaciens abundance and virulence. We are currently applying this technology to English walnut rootstocks, a crop in which crown gall disease can severely limit productivity.

Acknowledgments

Photography was by Don Edwards (University of California, Davis Dept. of Pomology). We are grateful to Dr. Thomas Burr and Dr. Lynn Epstein for providing A. tumefaciens strains and to Dr. Stan Gelvin for his helpful advice with the Arabidopsis tumorigenesis bioassays. We also thank Dr. George Bruening for his critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by funds obtained from the Walnut Marketing Board of California and University of California Biotechnology Strategic Targets for Alliances in Research (BioSTAR).

Abbreviations

- RNAi

RNA interference

- T-DNA

Agrobacterium-transferred DNA

- Ti

tumor inducing

- GUS

β-glucuronidase

- dpi

days postinoculation

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Bliss F A, Almedhi A A, Dandekar A M, Schuerman P L, Bellaloui N I. Hortic Sci. 1999;34:326–330. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith E F, Brown N A, Townsend C O. U S Dept Agric Bur Plant Bull. 1911;213:1–215. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerr A. Plant Dis. 1980;64:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chilton M-D. Sci Am. 1983;248:50–59. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kado C I. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:643–648. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelvin S B. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 2000;51:223–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu J, Oger P M, Schrammeijer B, Hooykaas P J J, Farrand S, Winans S C. J Bact. 2000;182:3885–3895. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.14.3885-3895.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petit A, Chantal D, Dahl G A, Ellis J G, Guyon P, Casse-Delbart F, Tempe J. Mol Gen Genet. 1983;190:204–214. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chilton M-D, Drummond M H, Merlo D J, Sciaky D. Nature (London) 1978;275:147–149. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Depicker A, Van Montagu M, Schell J. Nature (London) 1978;275:150–153. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klee H, Montoya A, Horodyski F, Lichtenstein C, Garfinkel D, Fuller S, Flores C, Peschon J, Nester E, Gordon M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1728–1732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.6.1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lichtenstein C, Klee H, Montoya A, Garfinkel D, Fuller S, Flores C, Nester E, Gordon M. J Mol Appl Genet. 1984;2:354–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ooms G, Hooykaas P J J, Moolenaar G, Schilperoort R A. Gene. 1981;14:33–50. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(81)90146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosher J M, Labouesse M. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:E31–E36. doi: 10.1038/35000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chuang C, Meyerowitz E M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4985–4990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060034297. . (First Published April 18, 2000; 10.1073/pnas.060034297) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith N A, Singh S P, Wang M B, Stoutjesdijk P A, Green A G, Waterhouse P M. Nature (London) 2000;407:319–320. doi: 10.1038/35030305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waterhouse P M, Graham M W, Wang M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13959–13964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bechtold N, Ellis J, Pelletier G. Comptes Rendus de l'Academie des Sciences Serie III: Sciences de la Vie. 1993;316:1194–1199. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fillatti J J, Kiser J, Rose R, Comai L. Bio/Technology. 1987;5:726–730. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jefferson R A. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1987;5:387–405. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kermouni A, Mahmoud S S, Wang S, Moloney M, Habibi H R. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1998;111:51–60. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1998.7085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gleave A P. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;20:1203–1207. doi: 10.1007/BF00028910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nam J, Matthysse A G, Gelvin S B. Plant Cell. 1997;9:317–333. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Astot C, Dolezal K, Nordstrom A, Wang Q, Kunkel T, Moritz T, Chua N-H, Sandberg G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14778–14783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260504097. . (First Published December 12, 2000; 10.1073/pnas.260504097) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Y, Christensen S K, Fankhauser C, Cashman J R, Cohen J D, Weigel D, Chory J. Science. 2001;291:306–309. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kooter J, Matzke M A, Meyer P. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4:340–346. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01467-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam J, Mysore K S, Zheng C, Knue M K, Matthysse A G, Gelvin S B. Mol Gen Genet. 1999;261:429–438. doi: 10.1007/s004380050985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nilsson O, Olsson O. Physiol Plant. 1997;100:463–473. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelvin S B, Gordon M P, Nester E W, Aronson A I. Plasmid. 1981;6:17–29. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(81)90051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsuda S, Kirita M, Watanabe Y. Mol Plant–Microbe Interact. 1998;11:327–331. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.4.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elomaa P, Helariutta Y, Kotilainen M, Terri T. Mol Breed. 1996;2:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penyalver R, Lopez M M. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1936–1940. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1936-1940.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]