Abstract

Objectives:

The present study aimed to assess oral health literacy level and its related factors among adult patients visiting Kerman Dental School.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Kerman Dental School clinic, among the first-time adult visitors. Individuals were selected randomly from volunteers who signed study consent forms. Background information and oral health literacy levels were acquired through the oral health literacy-adult questionnaire. Statistical analysis including the Chi-square test and independent t-test served for statistical evaluation of the study data.

Results:

Participants were 264 adults which consisted of 72.3% women and the mean age of 37 ± 8 years old. The mean oral health literacy score was 12.07 (out of 17), and 62.5% of the participants had an adequate oral health literacy level. There was a significant relationship between oral health literacy scores with gender, high level of education, and oral health behavior.

Conclusion:

The study participants had a good level of oral health literacy which can be correlated with their educational status and oral health information sources. An oral health educational program for less educated people is recommended.

Keywords: Health literacy, Iran, oral health

INTRODUCTION

Living a healthy life in the 21st century has many requirements such as being literate.[1] Literacy is not simply the ability to read and write; the UNESCO has defined literacy as the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate, and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts. Literacy involves continuous teaching to enable individuals to achieve their goals, increase their awareness, use their potentials, and have a bolder presence in a larger community.[2] With regard to the population aged 15 years and above, the UNESCO (UIS) reported that the global numbers of adults that are literate in 2010 were 84.1% (88.6% male and 79.7% female).

More attention has been given to health literacy in the past two decades. Parker et al.[3] reported health literacy primarily as the ability to exert literacy skills in relation to health matters such as prescriptions, visit cards, and pharmaceutical matters.

The most recent review carried out by Mårtensson and Hensing[4] introduced two approaches regarding the concept of health literacy. The first was the polarized phenomenon which concentrates on the high and low levels of health literacy, similar to the practical definition of health literacy. The second approach pointed out the reactional and critical skills required to improve health. Patients with lower literacy skills showed higher rates of misunderstanding of instructions given with prescriptions.[5]

Based on the history of health literacy, the most common definition of oral health literacy is “the level at which a person is capable of processing and understanding basic information regarding oral health and services related to it” and the concepts of this definition are necessary in making correct decisions in issues regarding health.[6] According to the health literacy constitution of the Institute of Medicine, oral health literacy is the struggle between culture and the society, the health system, and the education system such that ultimately all these factors contribute and facilitate to the results and costs of oral health.[7]

Wehmeyer et al. reported that low oral health literacy has a negative effect on the periodontal conditions of new and referred patients who visited the periodontology clinic in North Carolina University.[8] Oral health literacy studies showed limitations in the level of oral health literacy in certain groups such as people with lower education, the elderly, and the unprivileged population.[9,10,11]

A low level of health literacy has also been reported for Iran. Based on a National Survey in 5 provinces of Iran, 2 out of 3 adults living in Iran did not have sufficient health literacy skills.[12]

Considering the effect of culture and tradition and socioeconomic factors on the level of oral health literacy and the fact that these parameters vary greatly in different cities in Iran, this study tries to investigate the level of oral health literacy and its determinants in patients who visited Kerman Dental School clinic for the first time.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

It was a cross-sectional study and participants were randomly selected who were visiting the Kerman dental clinic for the first time. The inclusion criteria of the study were being 18 years old or older and were able to read and write in Persian language. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences (KMU-KA94/558). The oral health literacy adult questionnaire which was validated by Naghibi et al. was used in this study.[13] The questionnaire has 17 items in 4 sections that determine the individuals reading, listening, and decision-making skills regarding oral health. Data collection was done based on the questionnaire's instructions. The participants completed the questionnaire through a guided interview. Demographic data, oral health behavior such as frequency of brushing times, use of toothpaste, the last dental visit, smoking habits, and socioeconomic status of the person were recorded. On the basis of questionnaire instruction, the total score of the answers would be between 0 and 17. The scores could be categorized into three groups as follows: 0–9 as not enough OHL (low) score, 10–11 as medium score for OHL, and 12–17 as enough OHL (high) score.[13] Statistical tests such as Chi-square and independent two-sample t-test with a significance level of 0.05 were used to analyze the data.

RESULTS

There were 264 participants with a mean age of 37 ± 8 years old and 72.3% of them were females. Most (38.8%) of the participants had high school certificate (diploma).

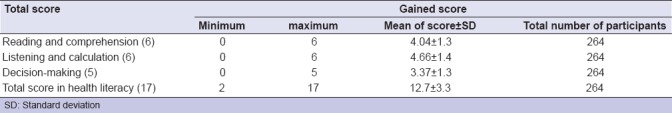

The information concerning acquired scores from the oral health literacy of individuals in different sections is presented in Table 1. The mean of the total score from different parts of the questionnaire was 12.07 ± 4.34 out of 17, and 62.5% of participants had enough or high level (more than 12 score) of oral health literacy.

Table 1.

Participants' scores in different sections of oral health literacy questionnaire

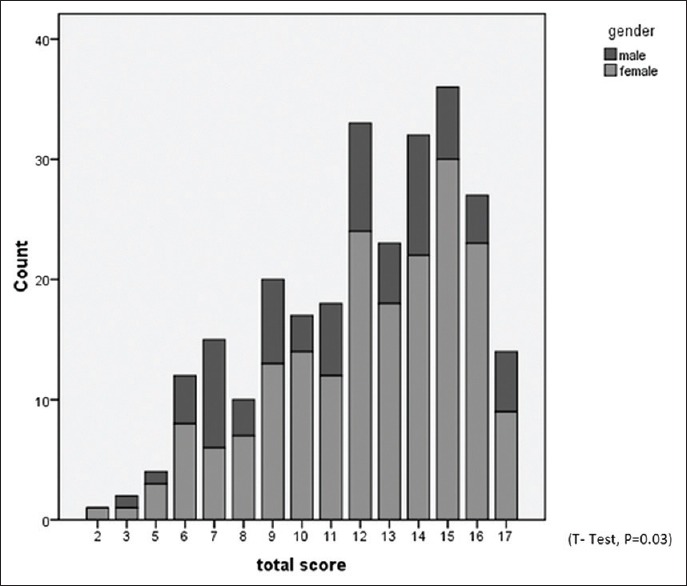

Comparison of mean score in oral health literacy between men and women showed a significant difference (P = 0.03) where women had a higher level of literacy [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of each question score on the basis of gender

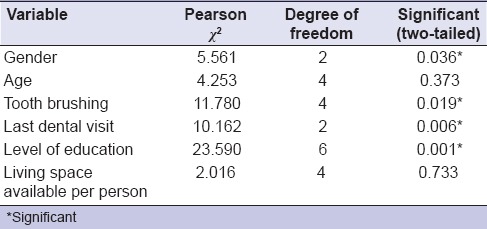

Level of oral health literacy had a statistically significant relationship with oral hygiene behaviors of the participants. Table 2 shows the relationship between different determinants with the obtained score from the questionnaire. Association of the determinants with oral health literacy was confirmed through adjusted regression analysis.

Table 2.

Relationship between oral health literacy score and different determinants

In self-assessment questions, 58% of the participants were satisfied with their oral health status and mostly stated that their source of information in the field of oral health was dentists.

DISCUSSION

Oral health literacy is one of the main parameters in determining the oral health status which has been verified in recent years by the World Health Organization.[14] The results of this study showed that 62% of the participants had a high level of oral health literacy whereas Naghibi et al.'s study[15] reported a lower rate of 40%.

The mean score acquired on the oral health literacy questionnaire in this study was 12, which was again higher than the average score (10.5) reported in Naghibi's study carried out in the capital city, Tehran, Iran. However, this could be due to the higher level of education of participants in this study. The results of the study are in line with a study by Sabbahi in Canada their frame of sampling.[16]

Studies in different countries analyzing the different levels of oral health literacy between gender reported no statistically significant difference,[9,10,16] although in Naghibi et al.'s study in Tehran female participants had a higher level of oral health literacy which agrees with the results of this study.[15] The reason for this is attributed to the fact that women tend to pay more attention to oral health and hygiene issues, also they use the oral health-related information provided by the media more often.

The level of oral health literacy was reported to be higher in those with a higher level of education which has confirmed the results of other studies in other parts of the world.[9,10,12,15] Thus, it can be concluded that training in the field of oral health is more necessary in those with lower levels of education. Results showed that the level of education affects the level of oral health literacy; therefore, it is suggested that educational programs in relation to oral health literacy be aimed at groups with lower literacy skills.

The level of oral health literacy has a statistically significant relationship with oral hygiene habits such as brushing and dentist visits, such that those with higher literacy levels brushed more and visited dentists more often. Previous studies showed that individuals with lower literacy skills had lower oral hygiene and brushed less.[17,18]

Consequently, organizing public education programs through the media in different groups of society could be helpful in improving the oral health literacy and lead to better overall oral hygiene status. The results showed no statistically significant difference among people of different age groups and different socioeconomic status; however, in Naghibi's study, it was reported that older groups had a lower level of literacy.[15] Other studies also showed that older age groups had a lower level of oral health literacy meaning they had a poor level of oral hygiene.[19] The difference here may be due to different levels of education.

To summarize, this study showed that patients who visited the dental school's clinic had a high level of oral health literacy; however, these results may not be a representative of the general population. Therefore, future studies among more generalized population are recommended.

CONCLUSION

The level of oral health literacy in patients visiting Kerman Dental School clinic was at an acceptable level. Unfortunately, there is still no feasible method to promote oral health literacy throughout the whole society; it is highly recommended that oral health educational programs be held with a special focus on older age groups and lower literacy level.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kanj M, Mitic W. Nairobi, Kenya: 2009. Health Literacy and Health Promotion.7th Global Conference on Health Promotion ’’Promoting Health and Development: Closing the Implementation Gap. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sector UE. Paris: United National Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; 2004. The Plurality of Literacy and Its Implications for Policies and Programs: Position Paper; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: A new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:537–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mårtensson L, Hensing G. Health literacy – A heterogeneous phenomenon: A literature review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26:151–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Tilson HH, Bass PF, 3rd, Parker RM. Misunderstanding of prescription drug warning labels among patients with low literacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63:1048–55. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institutes of Health. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wehmeyer MM, Corwin CL, Guthmiller JM, Lee JY. The impact of oral health literacy on periodontal health status. J Public Health Dent. 2014;74:80–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2012.00375.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atchison KA, Gironda MW, Messadi D, Der-Martirosian C. Screening for oral health literacy in an urban dental clinic. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70:269–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones M, Lee JY, Rozier RG. Oral health literacy among adult patients seeking dental care. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:1199–208. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JY, Divaris K, Baker AD, Rozier RG, Lee SY, Vann WF., Jr Oral health literacy levels among a low-income WIC population. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71:152–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tehrani Banihashemi S, Amirkhani MA, Haghdoost AA, Alavian S, Asgharifard H, Baradaran H, et al. Health Literacy and the Influencing Factors: A Study in Five Provinces of Iran. Strides Dev Med Educ. 2007;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naghibi Sistani MM, Montazeri A, Yazdani R, Murtomaa H. New oral health literacy instrument for public health: Development and pilot testing. J Investig Clin Dent. 2014;5:313–21. doi: 10.1111/jicd.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15:259–67. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sistani MM, Yazdani R, Virtanen J, Pakdaman A, Murtomaa H. Oral health literacy and information sources among adults in Tehran, Iran. Community Dent Health. 2013;30:178–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabbahi DA, Lawrence HP, Limeback H, Rootman I. Development and evaluation of an oral health literacy instrument for adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37:451–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2009.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pattussi MP, Peres KG, Boing AF, Peres MA, da Costa JS. Self-rated oral health and associated factors in Brazilian elders. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:348–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernabé E, Suominen AL, Nordblad A, Vehkalahti MM, Hausen H, Knuuttila M, et al. Education level and oral health in Finnish adults: Evidence from different lifecourse models. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javadzade SH, Sharifirad G, Radjati F, Mostafavi F, Reisi M, Hasanzade A, et al. Relationship between health literacy, health status, and healthy behaviors among older adults in Isfahan, Iran. J Educ Health Promot. 2012;1:31. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.100160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]