Abstract

Background & Aims

Recent studies have shown that cancers arise as a result of the positive selection of driver somatic events in tumor DNA, with negative selection playing only a minor role, if any. However, these investigations were concerned with alterations at nonrepetitive sequences and did not take into account mutations in repetitive sequences that have very high pathophysiological relevance in the tumors showing microsatellite instability (MSI) resulting from mismatch repair deficiency investigated in the present study.

Methods

We performed whole-exome sequencing of 47 MSI colorectal cancers (CRCs) and confirmed results in an independent cohort of 53 MSI CRCs. We used a probabilistic model of mutational events within microsatellites, while adapting pre-existing models to analyze nonrepetitive DNA sequences. Negatively selected coding alterations in MSI CRCs were investigated for their functional and clinical impact in CRC cell lines and in a third cohort of 164 MSI CRC patients.

Results

Both positive and negative selection of somatic mutations in DNA repeats was observed, leading us to identify the expected true driver genes associated with the MSI-driven tumorigenic process. Several coding negatively selected MSI-related mutational events (n = 5) were shown to have deleterious effects on tumor cells. In the tumors in which deleterious MSI mutations were observed despite the negative selection, they were associated with worse survival in MSI CRC patients (hazard ratio, 3; 95% CI, 1.1–7.9; P = .03), suggesting their anticancer impact should be offset by other as yet unknown oncogenic processes that contribute to a poor prognosis.

Conclusions

The present results identify the positive and negative driver somatic mutations acting in MSI-driven tumorigenesis, suggesting that genomic instability in MSI CRC plays a dual role in achieving tumor cell transformation. Exome sequencing data have been deposited in the European genome–phenome archive (accession: EGAS00001002477).

Keywords: Colorectal Cancer, Microsatellite Instability, Tumorigenic Process, Driver Gene Mutations, Positive and Negative Selection

Abbreviations used in this paper: bp, base pair; CRC, colorectal cancer; HR, hazard ratio; indel, insertion/deletion; MLH1, MutL Homolog 1; MMR, mismatch repair; mRNA, messenger RNA; MSH, MutS Homolog; MSI, microsatellite instability; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; NR, nonrepetitive; R, repetitive; RFS, relapse-free survival; RTCA, Real-Time Cell Analyzer; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; siRNA, small interfering RNA; UTR, untranslated region; WES, whole-exome sequencing; WGA, whole-genome amplification

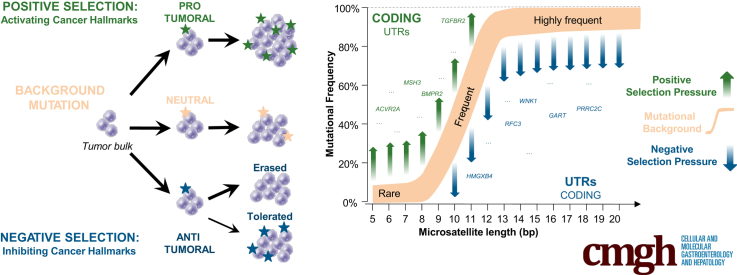

Graphical abstract

See editorial on page 349.

Summary.

Recent studies have shown that cancers arise as a result of the positive selection of driver somatic events in tumor DNA, with negative selection playing only a minor role, if any. The present work indicates that in microsatellite instability cancer, the high level of genomic instability generates both positively selected somatic mutations that contribute to the tumorigenic process but also recurrent somatic mutational events that are negatively selected due to their deleterious for the tumor cells.

Acquisition of the multiple hallmarks of cancer mainly is owing to somatic mutations. These hallmarks are a convenient organizing principle to rationalize the growth and complexity of tumors (for review, see Hanahan and Weinberg1). Underlying these mutations is the characteristic of genomic instability. This leads to the generation of mutant genotypes that confer advantages or disadvantages to the cells in which they occur, thus allowing the cells to dominate or to involute within the tumor mass.2 Data obtained from the analysis of thousands of tumors from different primary sites have shown that unlike species evolution, positive selection outweighed the negative selection of somatic mutational events during tumor progression.3, 4

Different types of genomic instabilities have been described in human malignancies, including a subset of cancers that is characterized by inactivating alterations of mismatch repair (MMR) genes.5, 6, 7 These tumors show a distinctive phenotype referred to as microsatellite instability (MSI). MSI affects thousands of microsatellite DNA sequences, although numerous alterations also occur in nonrepetitive DNA sequences during tumor progression. This phenotype was first observed in tumors from individuals with the familial cancer condition known as Lynch syndrome, and later in sporadic colon, gastric, endometrial, and other cancer types.8, 9, 10 The activating BRAF V600E somatic hotspot mutation,11 affecting a nonrepetitive coding DNA sequence, plays an important role in the progression of sporadic MSI colorectal cancer (CRC). However, most somatic mutations with a postulated role in MSI tumorigenesis are found in microsatellites contained within coding regions, and to a much lesser extent in microsatellites contained within noncoding gene regions (eg, intronic splicing areas, or in the 5’ UTR or 3’ UTR).12 Because microsatellites constitute hot spots for mutations in MSI tumors regardless of their location in genes and the function of these genes, such frequent mutations could be neutral or even detrimental to tumorigenesis.13, 14 In accordance with this working hypothesis, we previously reported frequent inactivation of the HSP110 oncogenic chaperone in MSI CRC.15, 16, 17, 18

Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing have made it possible to identify all genetic changes in human MSI neoplasms. Kim et al12 reported a global view in 27 colon and 30 endometrial tumors with the MSI phenotype. With regard to the selection of MSI-driven events, these investigators did not take into account the strong influence of the length and nature of DNA repeats on the frequency of their instability, as shown earlier by several groups.14, 19, 20 Furthermore, nucleotide instability outside of DNA microsatellites was not investigated, even though this is an important part of the landscape of somatic changes in MSI CRC.21 Other studies have attempted to identify driver genes containing selected mutations, or to use various probabilistic models of unselected mutations in MSI CRC while ignoring negative selection, which is more difficult to establish.8, 22 A recent study reported that tumors with a mutator phenotype (including MMR-deficient cancers) acquired more positively selected driver mutations than other tumors, but found no evidence of negative selection.3 The latter study investigated substitutions at nonrepetitive sequences, without taking into account repetitive sequences that have high physiopathologic relevance in these tumors.

In the present study we performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) of 47 MSI CRCs and validated results in an independent series of 53 MSI CRCs from the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Overall, our results shed new light on MMR-deficient tumorigenesis and suggest that genomic instability in MSI CRC plays a dual role in achieving tumor cell transformation. They show hitherto unknown pathophysiological aspects of MSI colon tumors that could lead to novel therapeutic approaches specific for this tumor subtype.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Cohort of MSI CRC Patients Analyzed by WES

Forty-seven patients who underwent surgical resection for MSI CRC from the Hôpital Saint Antoine (Paris, France) were selected for this study. Tumor samples and adjacent normal tissue counterparts were collected and stored frozen at -80°C before DNA extraction. DNA was purified using the Qiamp protocol (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) as recommended by the manufacturer. Informed consent was obtained for all patients. Gene expression for 30 samples from this cohort was analyzed previously on the Affymetrix U133 plus 2 chips as described (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).23

Tumor Cohort of MSI CRC Patients for Survival Analysis

A total of 164 MSI CRC samples with available whole-genome amplification (WGA) DNA were analyzed further for association between MSI mutational events and relapse-free survival (RFS).16

Exome Data Analyses

WES

For the 47 pairs of MSI CRC and paired adjacent normal mucosa, 3 μg of genomic DNA was fragmented by sonication and purified to obtain fragments of 150 to 200 base pairs (bp). The oligonucleotide adapters for sequencing were ligated to DNA fragments and purified. After purification, exonic sequences were captured by hybridizing the sequences to biotinylated exon library baits, which then were captured with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads that complex with biotin (SureSelect Human All Exon Kit v5+UTR, 75 Mb; Agilent, Les Ulis, France). The eluted fraction then was amplified by 4–6 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cycles and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer as paired-end 75 bp (San Diego, CA). Image analysis and base calling were performed using the Illumina Real-Time Analysis Pipeline version 1.14 with default parameters. Read-sequence Fastq files were generated and quality control was checked following Illumina's recommendations and FastQC reports.

Overall mutation (single-nucleotide variant and insertion/deletion) calling

The exome data analysis was first performed using Illumina CASAVA 1.8.2 software (San Diego, CA), which includes reads mapping and variant calling. Exome sequencing data have been deposited in the European genome–phenome archive (accession: EGAS00001002477). Reads were aligned against the hg19 genome build (GRCh37 - Human genome assembly 19) with ELANDv2, a gapped and multiseed aligner that reduces artifactual mismatches and allows the identification of small insertions/deletions (indels) (≤10 nucleotide), which is mandatory for analyzing microsatellite instability. Casava then detects single-nucleotide variants and indel variants independently in the tumor and normal samples. To distinguish somatic from germline variants, the results are combined and a Fisher test for base distribution between normal and tumor DNA is computed. We then applied a previously described method24 to generate a list of somatic variants. Quality control filtering removed variants sequenced in <10 reads, with <3 variant calls or with a Quality-Phred of <20. Variants were considered to be of somatic origin when the frequency of variant reads was ≥10% in the tumor and <5% in the normal counterpart, with significant enrichment of variant calls in the tumor as assessed by the Fisher exact test (P < .05). Variants then were annotated with Annovar for gene symbol, gene structure location, and exonic functional impact using the RefGene database (hg19 version). Common polymorphisms with a reported frequency of >1% were removed after comparison with the 1000 Genomes Project database and a proprietary database of exomes from normal tissues. Variants were functionally annotated using the annotations provided by Annovar based on the LJB databases (include SIFT scores, PolyPhen2 HDIV scores, PolyPhen2 HVAR scores, LRT scores, MutationTaster scores, MutationAssessor score, FATHMM scores, GERP++ scores, PhyloP scores, and SiPhy scores). When the annotation was not provided, PolyPhen2, Sift, and Provean software were used. If at least one of the methods defined the mutation as damaging, the mutation was annotated as deleterious. The mutation incidence in each tumor was evaluated by dividing the number of somatic mutations by the number of exonic bases covered by ≥10× in both the tumor and normal samples. Mutations were classified into nonrepetitive (NR) and repetitive (R) sequences using the microsatellite list defined with MSIsensor (see later).

Mutation calling in microsatellite sequences

To analyze mutations extensively at microsatellite sequence sites, we used the software MSIsensor25 version 0.2, a program for detecting somatic microsatellite changes. First, the list of microsatellites was generated using the scan command of MSIsensor, which searches for sequences of 1–5 bases repeated at least 5 times in the human reference genome sequence (NCBI build37.1 genome fasta file). Then, using the MSIsensor msi command, the mutation status for each microsatellite site (with ≥20 mapped reads) and each tumor/normal tissue pair was estimated by comparing the read-length distribution between tumor and normal samples using the chi-square test. P values for each microsatellite were extracted from MSIsensor outputs and used to define the microsatellite mutation status (if P < .05, the microsatellite was considered to be mutated). Each microsatellite was annotated for gene symbol and gene region type location (exonic, intronic, 5’ UTR, and 3’ UTR) using Annovar, according to the RefGene database (hg19 version).

Driver mutation selection in nonrepetitive sequences

Casava mutation (SNV and indel) calling results in coding regions was defined by Annovar and outside repetitive sequences. We applied MutSigCV (v1.4) and Intogen online software with default parameters. Many genes previously published as potential drivers in MSI CRC were not found with those 2 gold standard methods. To allow recovering these genes, we implemented a simpler method: intrasample binomial laws are fitted to report the different probabilities of mutation from one sample to another; given a sequence, its probability to be mutated at least once is calculated in each sample according to the corresponding binomial law; these probabilities then are combined across samples using the Fisher combined probability test. The resulting statistics then are compared with an empiric null distribution drawn using intronic and synonymous mutations.

Driver mutation selection in repetitive sequences

For each repeat , we observed the following: a count with values in [0, ni], where ni is the number of observed tumor samples for this repeat, and the repeat length xi (with values from 5 to 27). We tried logistic models on the data but they miss fitting our data well enough for 2 reasons: the observed mutation proportion for 1 repeat never goes to 1, and we observed overdispersion as compared with the logistic model. We consequently added the parameter to adjust for the first observation and chose a 2 layer-model to model the overdispersion.26 The model contained 2 layers. In the first layer, let and , where β stands for the β distribution. The random variable πi has moments equal to and with . In the second layer, the distribution of Yi conditionally to is , the joint distribution of then is proportional to , where is the β function at points et. The marginal distribution of then is proportional to , where is the gamma function. The log-likelihood term for individual then equals ( up to a constant (depending on and ).

To take into account the presence of outliers in the data, a parameter was added in the probability , in the same fashion as described by Tibshirani and Manning,27 which becomes . To overcome the high dimensionality of our model, we added a lasso penalty.27 The optimization problem to solve is as follows: . It is performed through a proximal-stochastic gradient descent (see Bertsekas28). All algorithms were developed in Python 3.5 and are available on request. The regularization parameter in the lasso usually is chosen through cross-validation. However, in our context, this technique does not seem relevant. Hence, cross-validation techniques split the data in training and testing sets, fitting the model on the training set and measure its performance on the testing set, across a grid of tuning parameters to choose the best. The problem here is that we obviously cannot learn the outlyingness of an observation thanks to other observations. In other words, what we learn in the training parts is not useful for the testing parts. Moreover, the result of the cross-validation would highly depend on how the outliers are distributed in the sets. Therefore, we used a heuristic technique of the L-curve, allowing us to choose a , providing us with a high likelihood together with control of the number of outliers. Once the hyperparameters and were estimated, Pearson residuals29 were calculated for each repeat. We then applied the Benjamini Hochberg Yekutieli multitest procedure to detect significantly large residuals. Repeats with detected residuals were finally assigned to the positively selected, respectively the negatively selected when their associated residuals were negative, respectively positive.

Functional analysis in CRC cell lines and primary colon tumor samples

To analyze for the enrichment of genes belonging to specific biological processes (Gene ontology), mutated genes that were positively or negatively selected were analyzed using DAVID30 against the Homo sapiens database (P < .05; number of genes, ≥5).

CRC cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). All cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C supplied with 5% CO2. All cell lines were mycoplasma free. Primary tumors and normal colon tissues were obtained from patients with CRC undergoing surgery at the Hospital Saint-Antoine between 2009 and 2014 and after informed patient consent was obtained and approval from the Institutional Review Boards/Ethics Committees of Hospital Saint-Antoine (Paris, France). Patients with CRC (1998–2007) from 6 centers involved in a study of MSI status were described previously.

Mutation Analysis

Specific primers for exonic coding of DNA repeats of negatively selected gene mutations were designed using AmplifiX software (V1.7). PCR amplification was performed on tumor DNA amplified by WGA technology using the Illustra GenomIphi DNA Amplification V2 kit (GE Healthcare, Velizy-Villacoublay, France). Absence of artifactual alteration of microsatellite sequences caused by WGA was validated by comparing Amplified Fragment-Length Polymorphism traces of several long microsatellites before and after WGA on a 3100 GA (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Fluorescent PCR products were run on an ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer with GS400HD ROX size standard and POP-6 polymer (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and Gene mapper software (V4.0, Thermofisher Scientific) was used to analyze negatively selected mutations in exonic microsatellite traces (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Oligonucleotide sequences are available on request.

Transient Gene Silencing by Cell Transfection and Treatments

A total of 1.25 × 105 cells were cultured in a 6-well plate for 24 hours. Cells then were transfected with Silencer Select (Thermofisher Scientific) small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (2 targets per gene) using Lipofectamine RNAimax according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Thermofisher Scientific). siRNA inhibition was assessed 48 hours after transfection by real-time quantitative PCR (Thermofisher Scientific). To induce apoptosis, 48 hours after transfection the cells were treated with TRAIL agent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, États-Unis) for 3 hours at 50 ng/mL (FET) or for 4 hours at 30 ng/mL (HCT116), 100 ng/mL (SW480, RKO, and SW620), and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Analysis of Cell Apoptosis

Apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry using an Annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate and 7-amino-actinomycin D staining kit (Beckman Coulter, Inc, Brea, CA) 48 hours after transfection. Cells were detached using StemPro Accutase cell dissociation reagent at room temperature for 10 minutes and stained with reagents according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Each sample was evaluated by flow cytometry (Gallios, Beckman Coulter, Inc). Data were analyzed using Kaluza Flow Analysis Software (Beckman Coulter, Inc).

Real-Time Cell Proliferation, Migration Monitoring, and Data Analysis

HCT116 cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 104 cells/well into E-plate 16 (ACEA Biosciences, Inc, San Diego, CA) and monitored on the xCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analyzer (RTCA) Dual Plate instrument (ACEA Biosciences, Inc) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell proliferation was assessed by electrodes in chambers and impedance differences within an electrical circuit were monitored by the RTCA system every 15 minutes for up to 50 hours. Cell migration was assessed using a CIM plate device of the xCELLigence system. The CIM plate consists of 2 chambers separated by a microporous membrane (pore size, 8 μm) attached to microelectrodes. In this case, the cell index calculated on the basis of impedance measurements reflects the number of cells that migrate through micropores monitored by the RTCA system every 15 minutes for up to 50 hours. These differences are converted into a cell index. The baseline cell index is determined by subtracting the cell index for a cell-containing well from the cell index of a well with only culture media. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least 3 times. The cell index was expressed as the means ± SEM from at least 3 independent experiments.

Transfection With Short Hairpin RNAs and Xenografts

Cloning of the pEBV (Epstein-Barr Virus plasmid) siRNA vectors and establishment of silenced cells were performed as described previously.31 We used the DSIR program (Designer of Small Interfering RNA) to design short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences to target the WNK1 and PRRC2C genes. RNA interference sequences targeting the genes are available on request. Cells carrying the pBD650 plasmid that expressed a scrambled shRNA sequence were used as a control. Cells were plated 24 hours before transfection with Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (Thermofisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were trypsinized and seeded in culture medium supplemented with hygromycin (125 μg/mL for the HCT116 cell line or 250 μg/mL for the SW480 cell line). After 2 weeks, gene silencing was monitored by reverse-transcription quantitative PCR analysis. Ten million HCT116 or SW480 cells transfected with shRNA were injected subcutaneously into the flank of female nude mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) at 6 weeks of age. Tumor size was measured with a caliper every 2 days over 30 (HCT116 cell line) or 28 (SW480 cell line) days. Mice were killed when the tumors reached 1500 mm3. The mice were treated according to guidelines from the Ministère de la Recherche et de la Technologie (Paris, France). Statistical methods to predetermine sample size in mice experiments were not used and the experiments were not randomized. During experiments and outcome analysis, the animal group allocations were not blinded. All experiments were conducted according to the European Communities Council Directive (2010/63/UE) for the care and use of animals for experimental procedures and complied with the regulations of the French Ethics Committee in Animal Experiment (committee: Charles Darwin) registered at the Comité National de Réflexion Ethique sur l’Experimentation Animale (Ile-de-France, Paris, France). All procedures were approved by this committee. All experiments were supervised by an author (A.C.) and all efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Immunohistochemistry

Briefly, 4-μm–thick sections of paraffin-embedded tissue samples were cut onto silane-treated Super Frost slides (CML, Nemours, France) and left to dry at 37°C overnight. Tumor sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in pure ethanol. Before immunostaining, antigen retrieval was performed by immersing sections in citrate buffer, pH 6.0 (WNK1) (15 min at 95°C), washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 3 minutes, and treated with 3% H2O2-PBS for 15 minutes to inhibit endogenous peroxidases. After washing in PBS, slides were saturated for 25 minutes in 3% bovine serum albumin PBS. Sections then were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with antibody to WNK1 (dilution 1/100; clone ab128858; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom). After washing in PBS, secondary antibody (8114P; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) was added for 30 minutes at room temperature. Slides were washed twice for 5 minutes in PBS and shown using the Novared kit (Vector, Burlingame, CA). Slides were washed twice in water for 5 minutes and counterstained with 10% Meyer's hematoxylin. After 1 wash in water, slides were dehydrated in 100% ethanol and in xylene for 30 seconds each. Apoptosis was quantified by counting the number of labeled cells with anti–caspase 3 antibody per 100 tumor cells in the most affected areas.

Survival Analysis

In the cohort of 164 MSI CRC patients, the association between mutations and survival was assessed by multivariate Cox proportional-hazards regression analyses and adjusted by TNM stage. This was performed for 5 negatively selected target MSI mutations. This also was performed for a Boolean mutational index that was calculated from the mutational status of the 5 target genes in each tumor sample. The proportional-hazards assumption was tested using the cox.zph function. RFS was used and defined as the time from diagnosis to first relapse time or death from a cancer cause only. The cut-off point for statistical significance was .05.

Results

Exome-Wide Analysis of MMR-Deficient CRC: Genomic Instability at Nonrepetitive and Repetitive DNA Sequences

We examined WES data from 47 primary MMR-deficient CRCs defined as having MSI according to international criteria.32, 33 The genome fraction covered by WES was 75 MB, including UTR (37%), coding exonic (56%), and intronic (7%) regions. Repetitive DNA sequences represent less than 3% of the genome fraction covered by WES (roughly 2 Mb of 75 Mb), with 56% in intronic, 19% in coding exonic, and 25% in UTR regions (Figure 1A). Computational methods were used to identify somatic mutation events at both NR and R DNA sequences (see the Methods section for futher details). Investigations were restricted to mononucleotide R sequences because these are the most frequently affected by somatic mutations in MMR-deficient cells and often are located in coding regions or in noncoding UTR sequences endowed with putative functional activity.12 Repeats of at least 5 nucleotides in length were considered, in accordance with the definition of DNA microsatellite sequences. Mutations in R and NR sequences occurred in similar proportions, representing on average 60% and 40% of all somatic events, respectively (Figure 1B). These mutations accumulated in parallel in MSI tumor samples (Figure 1B) (P = 2.47 × 10-14; R = 0.85). Relative to the fraction of covered genome, the mutation rate observed in R sequences was approximately 24-fold higher than in NR sequences, expectedly. No significant differences were observed between MSI CRC from Lynch syndrome and sporadic cases, or between tumors with different TNM stages (Figure 1B). A much higher number of mutations was observed in this MSI colon tumor cohort compared with the overall incidence of mutations reported for all CRCs34 (Figure 1C). This high rate of mutation resulted in a much higher proportion of genes with mutations in coding regions (6% vs 1%) (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Genetic instability in MMR-deficient CRC. (A) Pie chart represents the portion of R (light blue) and NR (dark blue) sequences. Bar plots represent the distribution of the 5 genomic region types (3’ UTR, coding exonic, intronic, 5’ UTR) captured by WES in R (light blue) and NR (dark blue) sequences. (B) Bar plot of the number of mutations per captured megabase (Nb mutations/Mb) across the whole exome for 47 MSI tumors in R sequences (light blue) and in NR sequences (dark blue). The median mutation rate in all types of CRC was described previously25 and is indicated by the red dotted line. The heatmap below shows the percentage of mutated genes in coding R and NR sequences. (C) Box plots show the number of mutations per megabase (log10 scale) in all types of CRCs from the TCGA colon adenocarcinoma data set (red), in MSI CRC within R sequences (light blue), and in MSI CRC within NR sequences (dark blue). Grey dots indicate the mutation frequencies for each MSI tumor. The results of the t test between groups were as follows: ***P < .001. (D) Bar plot of the percentage of genes with different mutation frequencies for MSI (blue) and microsatellite stable (MSS) (red) CRCs. (E) Box plots represent the number of mutations per megabase for 3 genomic regions (UTRs, coding exonic, intronic). Grey dots represent the value for individual tumors (n = 47). The results of the t test between groups were as follows: ***P < .001. (F) The mutation frequencies of 3 gene regions (UTRs, coding exonic, intronic) are shown, where grey dots represent each individual mutation in NR (left) and R (right) sequences. Mutation frequencies in R sequences are shown according to the microsatellite length and nucleotide composition (colored dots and lines). IHC, immunohistochemistry.

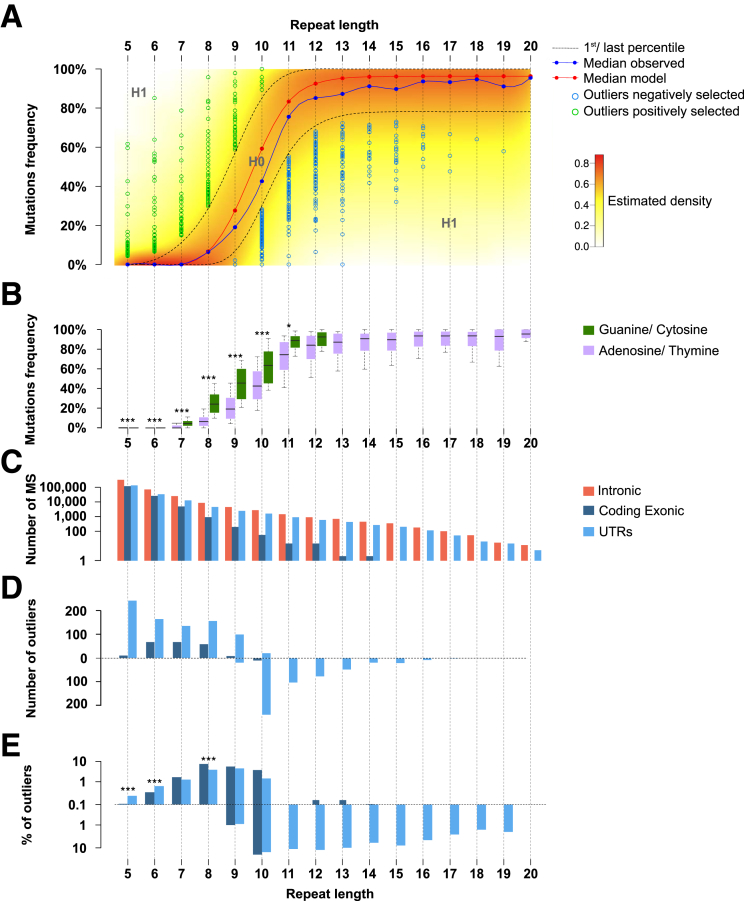

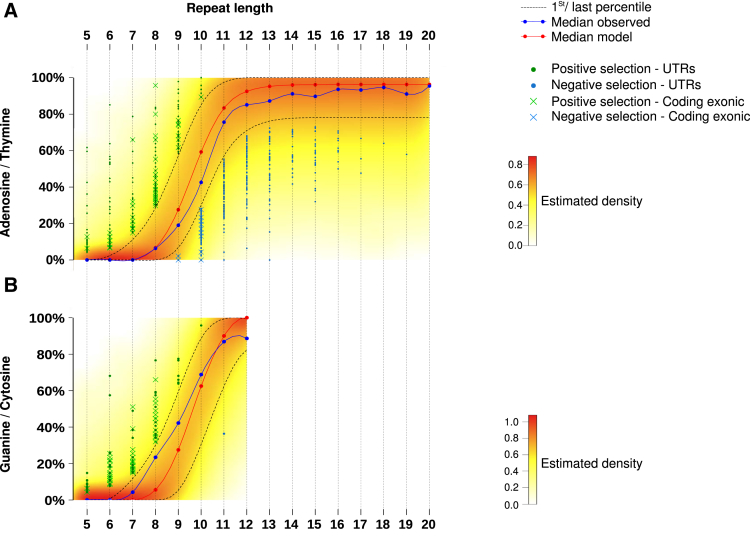

Mutation frequencies also were evaluated in coding, UTR, or intronic regions (Figure 1E and F). For both NR and R sequences, a significantly higher mutation frequency was observed in intronic compared with coding exonic and UTR regions of the tumor genome (Figure 1E), expectedly. We confirmed at the exome scale that both the length and composition amino acid constitution of these DNA repeats (A/T vs C/G) determine their mutational frequency (Figure 1F). There was almost 100% probability of mutation if the microsatellite repeat length was longer than 14 bp, consistent with previous results.13, 14, 20 Mutation events also were more frequent in G/C nucleotide repeats compared with A/T repeats. These observations indicated that distinct models are needed to analyze the occurrence of mutations in R and NR sequences in MMR-deficient tumors.

Modeling the Occurrence of Mutations in Coding, Nonrepetitive DNA Sequences Identifies Known and New Actors in MSI Colorectal Tumorigenesis

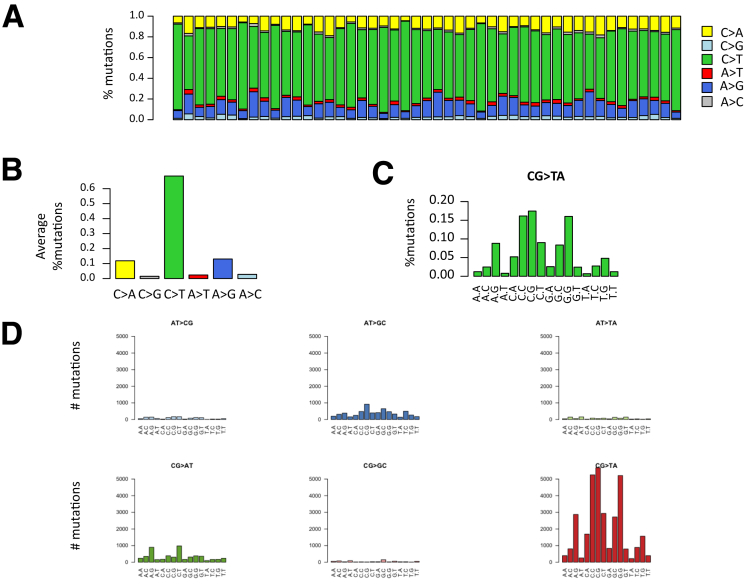

As shown in Figure 1, MSI colon tumors accumulate somatic mutations in R and NR DNA sequences at similar proportions. For NR sequences, the analysis of nucleotide substitutions in MSI tumors is shown in Figure 2. In coding sequences, they mostly consisted of nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions that probably were deleterious in the majority of cases (>50%) (Figure 3A). Only a small number of events in NR sequences were indels (Figure 3A), in line with a previous report.35

Figure 2.

NR mutation types. (A) Distribution of mutation substitution types within the sample. (B) Average proportion across the sample of each transition type. (C) Frequency of C to T mutations according to the flanking base. (D) Distribution of the number of mutations according to the flanking bases for each type of base substitutions.

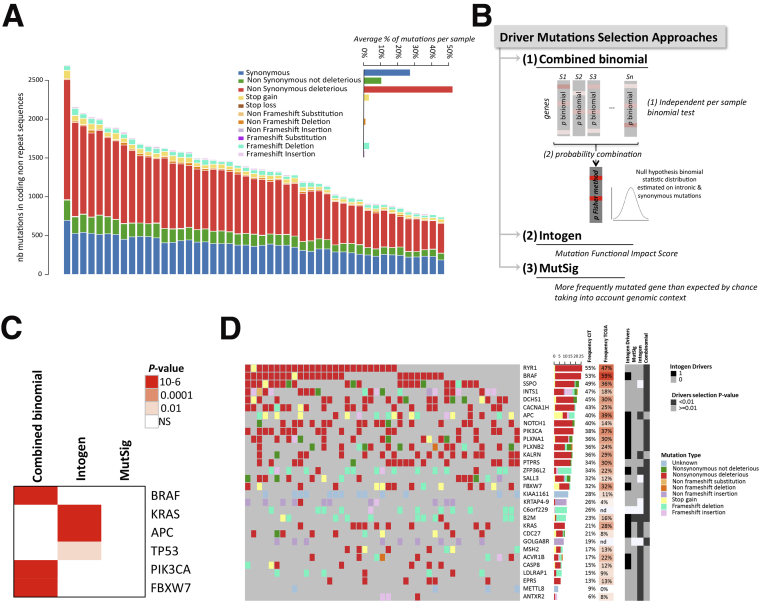

Figure 3.

Identification of candidate driver genes with mutations in NR sequences. (A) Distribution of mutation types in coding NR regions according to their functional impact (annotation tool Annovar). The functional impact was based on several methods, with a mutation considered as deleterious if at least 1 of those methods estimated it to be deleterious. The average percentage of each mutation type per sample is shown in the inset. (B) Schematic representation of the 3 methods (MutSigCV, Intogen, combined binomial) used in this study to identify driver mutations (see the Methods section for details). (C) Heatmap of the significance (q values) of mutated genes commonly described for their functional impact in MSI CRC using Intogen, combined binomial, and MutSigCV analyses. (D) Oncoprint representation of mutations in coding NR sequences within each sample for the 25 top significantly mutated genes (indicated in darker grey for each approach on the side annotation heatmap) and for the 5 significant genes considered as driver genes by Intogen (indicated in black on the side annotation heatmap) across samples. Top and side bar plots indicate the percentage of each type of mutation within the sample and within the gene, respectively.

We next aimed to identify mutational events in NR sequences that showed an abnormally high frequency in tumor DNA (ie, positively selected mutational events) (Figure 3B and see the Methods section for details). Overall, we identified the 141 most consensual driver genes of colon tumorigenesis (Figure 3C and Supplementary Table 1). The top 30 driver mutated gene list is shown in Figure 3D and Supplementary Table 2, and includes recognized master genes in colorectal oncogenesis such as BRAF, APC, KRAS, and PIK3CA (Figure 3C).

Modeling the Occurrence of Mutations in Repetitive Sequences Shows Positively and Negatively Selected Events in the MSI Tumor Genome

In cancer cells, somatic mutations occur randomly (mutational background) across the genome. In MSI tumor cells, DNA microsatellites constitute natural hot spots for these somatic events and the MSI tumor type is characterized by a high background of instability in repeat sequences. The mutability of DNA repeats within MSI tumors depends on functional and structural factors, as well perhaps on other as yet unidentified factors. Taking into account these previously described structural criteria,13 that is, repeat length and nucleotide composition (adenosine/thymine vs guanine/cytosine) (Figure 1), we developed a statistical model (see Methods for further details) that discriminated 3 functional categories of MSI-linked somatic mutations occurring at DNA repeats: the first category is positively selected events that confer benefits to the MSI tumor cells in which they occur because they have an oncogenic impact. These are believed to be positive drivers of the MSI-driven tumorigenic process and their mutation frequencies are higher than expected by chance in the model. The second category is negatively selected events that are deleterious for the tumor cells in which they occur because they have an anticancer impact. These are believed to be negative drivers of the MSI-driven tumorigenic process and their mutation frequencies are lower than expected by chance in the model. The third category is MSI-linked mutational events owing to background that do not confer benefits or have any oncogenic impact. Their mutation frequencies are found within the background level for MSI by the model. Although such neutral events are not thought to play a role during tumor progression, some gene alterations could have functional significance when they occur together.

Most allelic shifts were deletions and/or insertions of 1 bp, or more rarely 2 bp (data not shown). These were considered equally as mutant alleles in the genomic analysis of instability at mononucleotide repeats. A similar pattern was observed for dinucleotide repeats (data not shown). To build the model, only MSI-related events that occurred in mononucleotide R sequences were considered because these largely predominate over others such as in dinucleotide repeats8, 12 (see the Methods section for further details). Repeat length was used as an input parameter for the model and 2 models were fitted: one for A/T composition and the other for G/C composition (Figures 4B and 5). The density of the model for A/T composition of repeats is shown in Figure 4A. Microsatellites that were shown within our model, abnormally high or low mutation frequency within UTRs, or coding exonic regions are indicated (Figure 4A and Supplementary Table 3). Overall, we identified 1050 and 561 outlier events showing aberrant positive and negative selection in MSI CRC, respectively. These included 1376 mutations in UTR sequences (828 and 548 showing positive or negative selection, respectively) and 235 mutations in coding sequences (222 and 13 showing positive or negative selection, respectively). With the exception of these 13 frameshift mutations that affected coding DNA sequences (see later), negatively selected events were observed almost exclusively in noncoding microsatellites (UTRs). In contrast, positively selected mutations were observed in both coding and noncoding DNA repeats (Figure 4C–E).

Figure 4.

Positive and negative selection in repetitive sequences in MSI CRC. (A) Distribution model of mutation frequencies across samples in microsatellites in UTRs or coding exonic regions according to repeat length for A/T nucleotides. The color gradient indicates the density of the β-binomial logistic regression model. The blue curve represents the median of observed mutation frequencies, and the red curve represents the median obtained from the model. This figure shows the statistical model and outliers for adenosine/thymine. (B) Box plot representation of mutation frequency variations according to the nucleotide composition of the microsatellite and to the repeat length. The significant independence of the chi-squared distribution is annotated by asterisks as follows: *P < .05, and ***P < .001. (C) Distribution of microsatellite mutations (log10 scale) in the 3 gene regions (UTRs, coding exonic, and intronic) according to repeat length. (D) Distribution of outlier mutation in microsatellites contained in UTRs and in coding exons. Positively and negatively selected microsatellite mutations are represented above and below the dotted line, respectively. (E) Distribution of the percentage of outlier mutations (log10 scale) according to repeat length. The significant independence of the chi-squared distribution is annotated by asterisks, as follows: *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001.

Figure 5.

Outliers identification and visualization. Distribution of mutation frequencies of microsatellites according to repeat length. Green dots and blue dots represent microsatellites positively and negatively selected outlier mutations, respectively, in MSI tumors. Coding exonic outliers are indicated by a x and UTR outliers are indicated by a circle. This figure shows the statistical model and outliers for (A) adenosine/thymine and (B) guanine/cytosine.

According to our model, we could only identify negative selection at long DNA repeats, that is, those at least 9 bp in length (Figures 4A and 5). Because these long DNA repeats are mainly noncoding and located in UTR parts of human genes (5404 UTR candidates vs 248 in the coding DNA), the great majority of negatively selected mutations consequently were identified within UTR DNA repeats. However, when the number of negatively selected events was normalized by taking into account the overall number of microsatellites in coding and UTR regions (Figure 4C–E), no significant enrichment for negative selection in UTR vs coding repeats was observed in MSI CRC (13 of 267 [4.9%] vs 548 of 7030 [7.9%], respectively). Overall, our analysis of MSI through exome sequencing led us to identify 563 mutations that were negatively selected in MSI CRC, representing <10% of the candidate coding and UTR DNA repeats with a size ≥9 bp as described earlier.

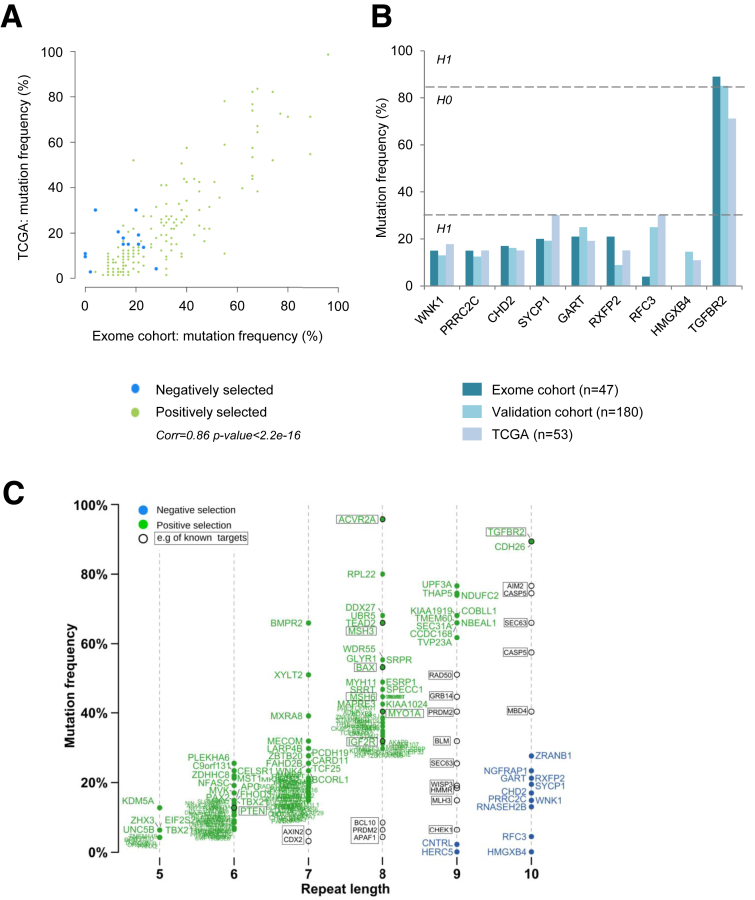

Validation of Exome-Wide Analysis of MSI and Refining the List of MSI Target Genes in MSI CRC

We next compared our results with those of the TCGA consortium, which used MuTect2 caller in 53 MSI CRC. The mutation frequencies observed at microsatellite loci were highly similar in both cohorts (R = 0.86; P < 2.10-16) (Figure 6A). Instability at 9 microsatellite loci also was investigated using PCR and Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism in an independent cohort of 180 MSI CRCs. By using this manual gold standard method, very similar mutation frequencies were observed for these 9 coding repeat sequences in the 2 cohorts with the 2 methods, including 8 in which we validated the low mutation frequency (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Mutation frequency validation and redefinition of true MSI target genes. (A) Mutation frequency of outlier mutations observed in the present exome cohort and in the TCGA cohort. (B) Mutation frequency for the 9 outlier mutations coding microsatellites contained in the putative target genes for MSI in a large independent cohort of colon tumors (n = 180) and the TCGA cohort (n = 53). (C) Distribution of mutation frequencies in coding microsatellites according to repeat length (x-axis). Genes with coding exonic outlier mutations identified in this study are indicated in green (positively selected) and blue (negatively selected). Genes with background mutation rates (unselected according to the model) are indicated in black. Examples of published targets for MSI are shown within rectangles, and those not subject to selection are indicated in black text.

According to the published literature, the majority of known and extensively analyzed target gene mutations in MSI CRCs were found here in MMR-deficient CRCs. These included AXIN2, CDX2, BCL10, APAF1, CHCK1, PLH3, BLM, RAD50, WIP3, MBD4, CASP5, and AIM2 (Figure 6C). However, TGFBR2, ACVR2A, BAX, MSH3, MSH6, IGF2R, and several others remained in the group of genes with positively selected mutations in MSI tumors. Interestingly, this group mostly contained a small coding repeat (5–7 bp in length) whose mutation frequency was not high but nevertheless was subjected to strong positive selection pressures according to our model (eg, UNC5B, PTEN, and APC). Finally, our signature also contained a small number of target genes with a long coding repeat (9 or 10 bp in length) whose mutations were negatively selected in MSI tumors (Figure 6C) and in which we further assessed the functional impact (see later).

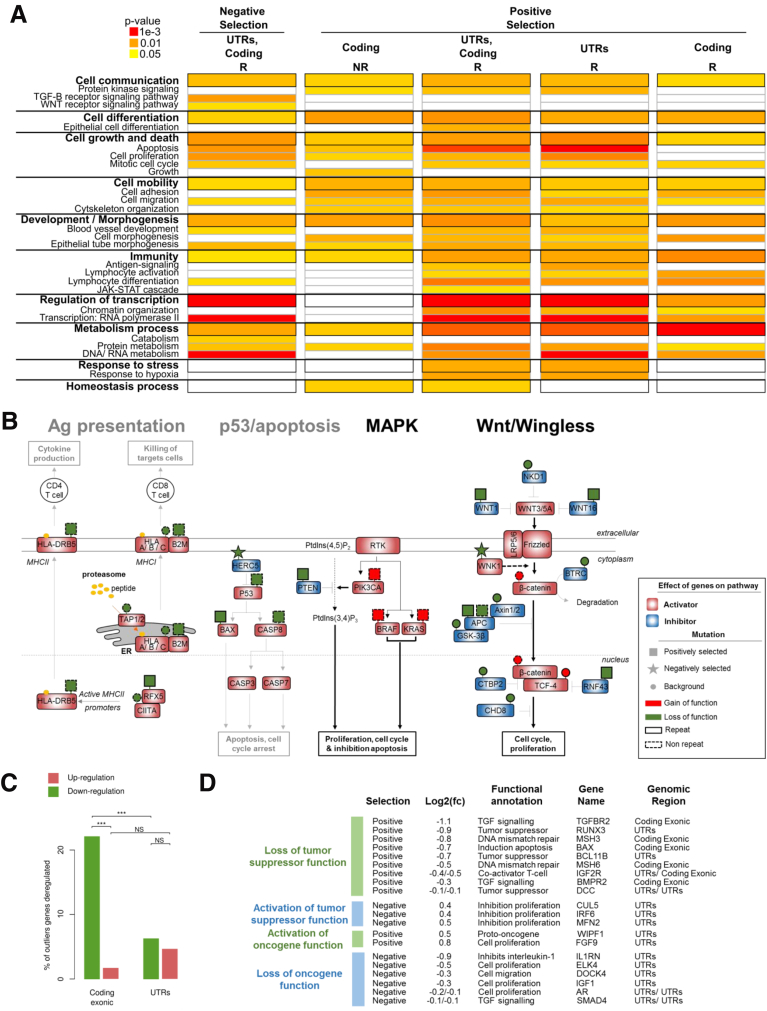

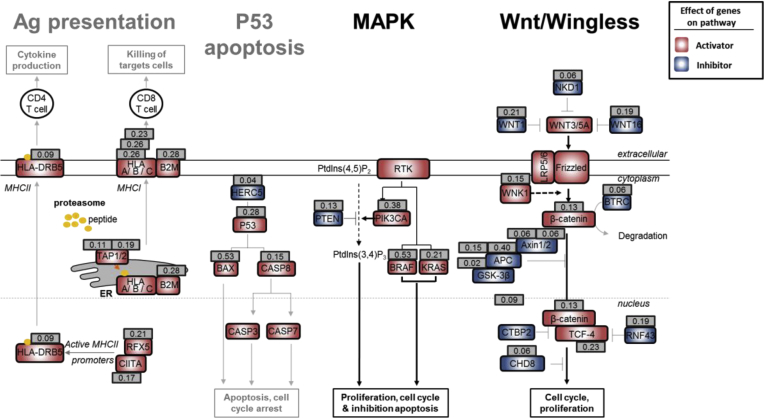

Investigating the Interplay Between MSI, Changes in Gene Expression Level, and Cancer-Related Pathways

We next tested the hypothesis that both positively and negatively selected outlier mutations in R sequences constitute major events in MSI tumorigenesis that result in pro-oncogenic or anti-oncogenic impacts, respectively. To do this we assessed gene ontology terms associated with these mutations and found several to be enriched significantly in such events (Figure 7A and Supplementary Table 4). These outlier mutations were observed in cancer-related pathways known to play an important role in tumor development (eg, Wnt/Wingless and RAF/RAS/MAPK signaling), or with antitumor immunity. Their positive or negative selection in MSI tumors were likely to accord with their expected positive or negative impact, respectively, on the activity of these pathways in CRC (Figures 7B and 8).

Figure 7.

Participation of positively and negatively selected events in cancer-related pathways. (A) Significant gene ontology terms enriched in outlier mutations compared with their abundance in all genes in the genome. Details of all gene ontology terms are available in Supplementary Table 4. (B) Interactions between mutations in R (continuous outlines) and NR sequences (dotted outlines) result in a coordinated effect on 4 signaling pathways. The effects of mutations that are unselected (circles), positively selected (rectangle), or negatively selected (stars) are indicated above the genes by a color code (red for gain of function and green for loss of function). Prediction of the global effect of mutations is represented by bold font for activation of the pathway and light grey font for inhibition. Genes known to be positive regulators (activators) of signaling pathways are indicated by a red rectangle and negative regulators (inhibitors) are indicated by a blue rectangle. (C) Percentage of outlier mutations in R sequences located in coding exons and in UTRs leading to significant dysregulation of mRNA expression level (comparison of mutated and wild-type tumors in each case). Upper: Proportion of microsatellite mutations leading to up-regulation of gene expression (in brown); lower: Down-regulation (in green). The significant independence of the chi-squared distribution is annotated by asterisks, as follows: ***P < .001. (D) List of MS candidate outliers that may contribute to the MSI tumor phenotype because of their biological functions, the effect of mutations on the level of gene expression, and the selective pressure at which the MS is constrained (positive or negative selection). Log2(fold change (Log2(fc))) indicates the log base 2 of mRNA expression between the MS mutant allele vs MS wild type. For each gene, the selective pressure, biological function, gene name, and the gene region of the MS are indicated.

Figure 8.

Mutation frequency of selected pathways. For each gene that belongs to a specific biological pathway, the mutation frequency is indicated in a grey square. Ag, Antigen; MAPK, Mitogen Activated Protein Kinases.

We then assessed whether these outlier mutations influenced the expression level of the corresponding target gene in MSI tumors. Several mutations in coding regions and in UTRs were associated with significantly altered gene expression when assessed at the messenger RNA (mRNA) level using transcriptome data from 30 MSI CRC samples (Figure 7C). Because of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay,36 we mostly observed down-regulation of mutated transcripts from coding regions, as expected. The overall impact of outlier events in UTR tracts was mixed, with down-regulation or up-regulation of a few target genes in MSI CRCs. Based on these results, a list of outlier mutations expected to play an important role in MSI tumor development was proposed (Figure 7D). In line with a protumorigenic effect, positively selected outlier events may inactivate tumor-suppressor functions by down-regulating mRNA expression or activate oncogene functions by up-regulating mRNA expression. Acting in opposition, the negatively selected outlier events could activate tumor-suppressor functions by up-regulating mRNA expression or inactivate oncogene functions by down-regulating mRNA expression, thereby slowing down MSI tumorigenesis.

Functional Validation of the Deleterious Impact of Negatively Selected Coding Mutations on CRC Cells

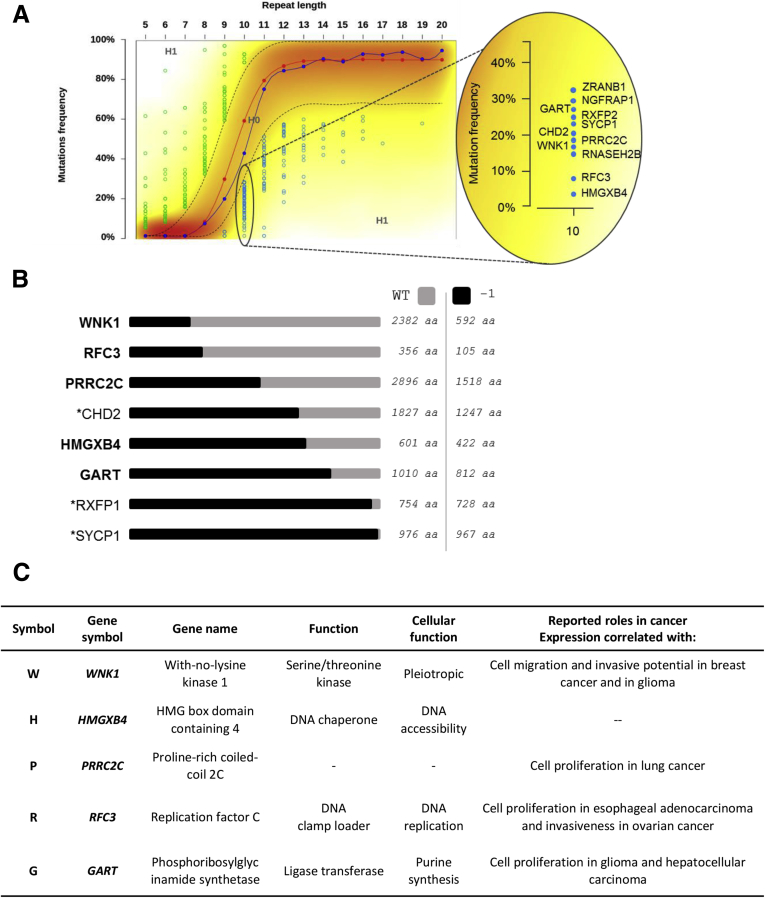

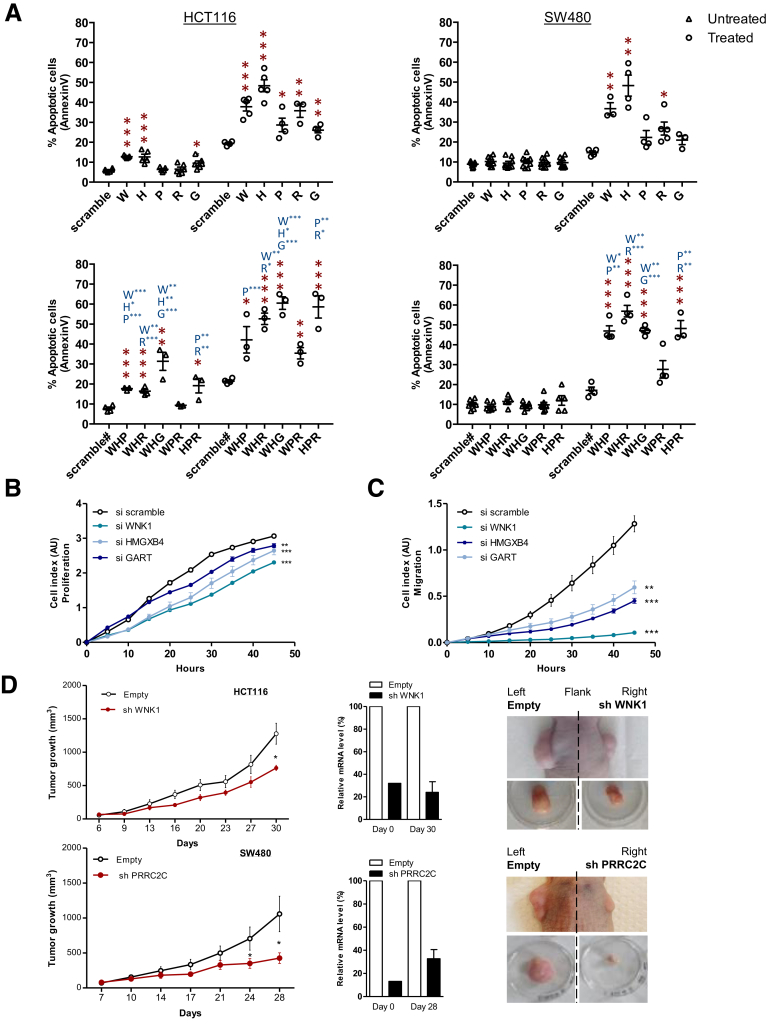

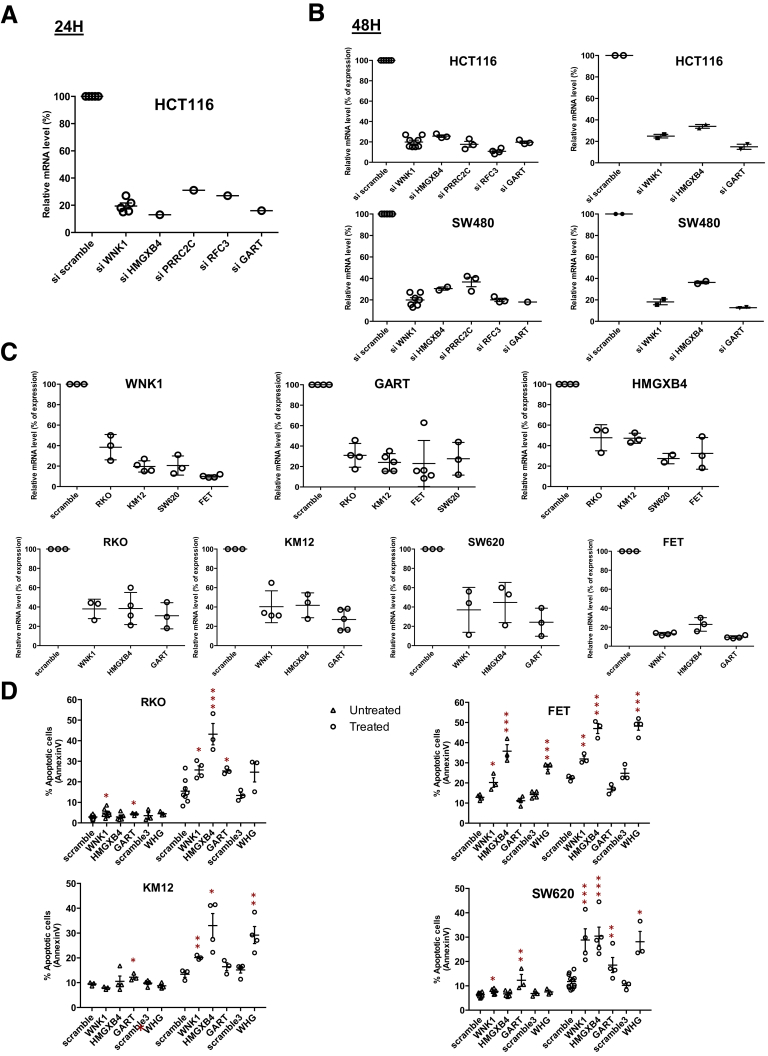

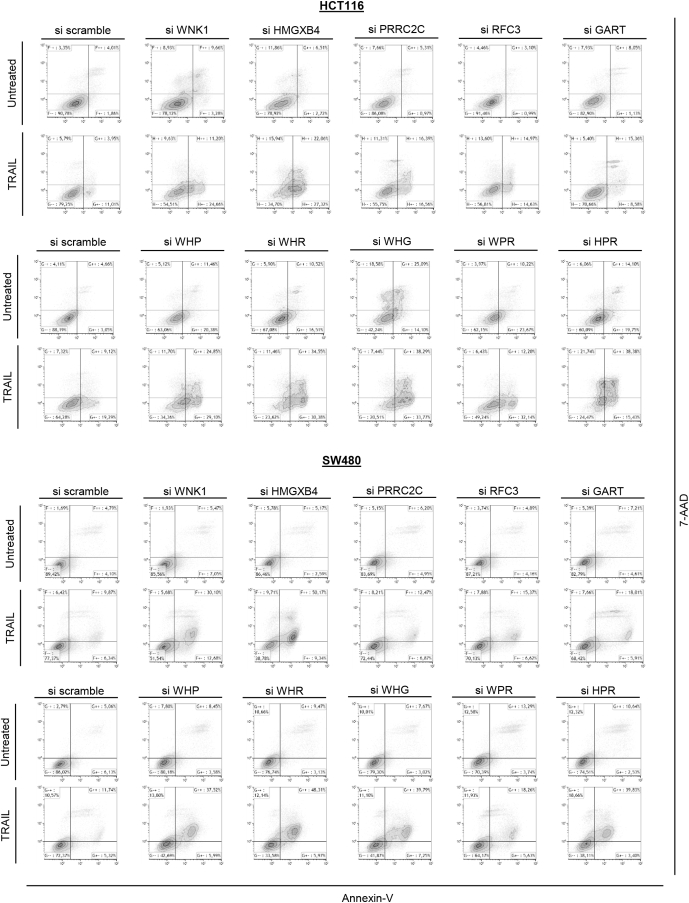

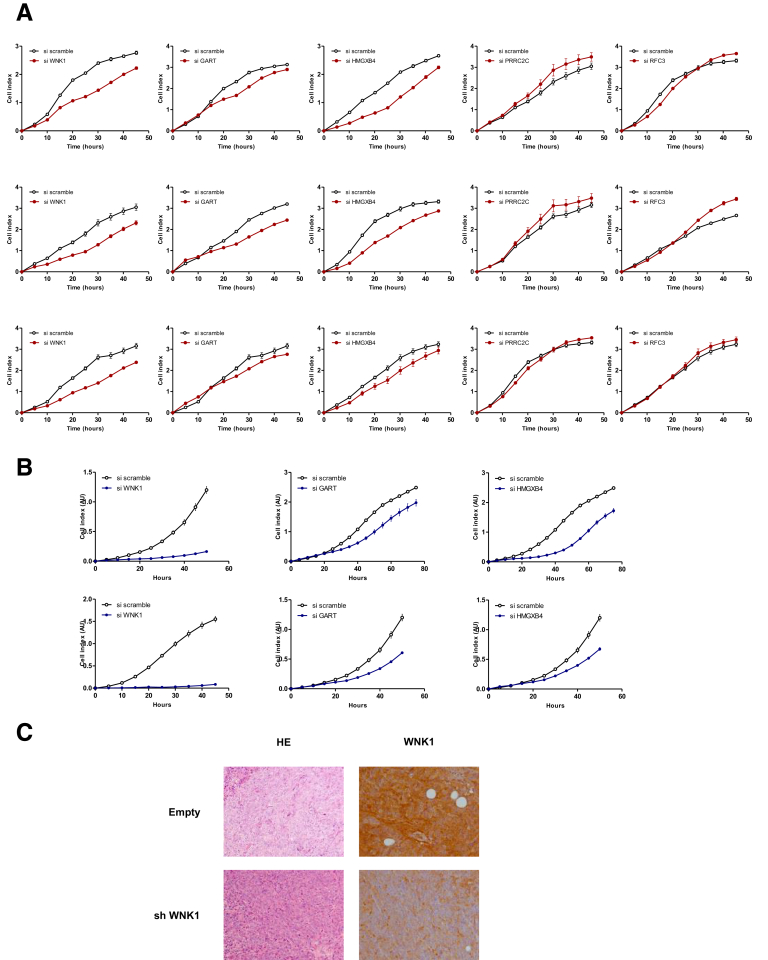

In MSI tumors, mutations observed in repetitive coding sequences are frameshifts (indels) and generally lead to truncation of the corresponding aberrant protein. Although these events are usually loss-of-function mutations, nonsense-mediated mRNA decay acts to degrade mutant mRNAs that may encode proteins with residual functional activity because these transcripts contain a premature termination codon. We therefore hypothesized that negatively selected mutational events identified in the genomic screen shown in Figure 6 could be deleterious for MSI tumor cells. As stated earlier, only a few of these events were in coding regions and led to truncation of the respective proteins (eg, WNK1, PRRC2C, CHD2, SYCP1, GART, RXFP2, RFC3, and HMGXB4) (Figure 9). Five of these target genes (WNK1, HMGXB4, PRRC2C, RFC3, and GART) were selected according to their documented role as reported in the literature (Figure 9). To test the hypothesis that truncation of these candidate proteins resulting from MSI was responsible for their inactivation, we investigated the functional consequences of their silencing using siRNA and/or shRNA in CRC cell lines in vitro and in vivo using xenograft models (Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13). Depending on the target gene, their inactivation in CRC cells led to deleterious effects on apoptosis, proliferation, and/or cell migration (Figures 10A–C, and Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13). Of note, the deleterious effects were greatly enhanced when several of the targets were silenced concomitantly in the same cellular models, indicating additive effects for these events in CRC cells (Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12). In additional experiments, the prolonged silencing of some of these targets led to strong inhibition of tumor growth in HCT116 (MSI) and/or SW480 (microsatellite stable) xenografts (Figures 10D and 13).

Figure 9.

Exonic outlier mutation genes: mutation positions and negative selection validation. (A) Negatively selected coding exonic outliers identified in this study (repeat length: 10). (B) Schematic structure of wild-type (in grey) or mutant (in black) proteins of the 9 outlier mutation genes in which mutations were negatively selected in MSI tumors. *Genes that are not investigated in the present study because mutations do not match with putative loss of function (RXFP1, SYCP1, RNASEH2B) or because gene silencing was not successful (CHD2). (C) Table of the 5 outlier mutations negatively selected in MSI tumors identified from exome sequencing data and investigated here by functional analysis. Four of the 5 genes have a literature-documented role that supports negative selection of their mutations because of the tumorigenic implication.

Figure 10.

Validation of the deleterious effects of 5 outlier mutations on CRC cell lines. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of the apoptosis (Annexin V) of untreated (triangle) or TRAIL-treated (circle) HCT116 (MSI, left panel) and SW480 (microsatellite stable, right panel) CRC cell lines transfected with either a single specific siRNA gene (WNK1, HMGXB4, GART, RFC3, and/or PRRC2C), or with scrambled siRNA (upper panels). Lower panels: Simultaneous down-regulation of 3 genes are shown, leading to an additive effect in increasing the percentage of apoptotic cells in some cases. Data represent the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments for single specific siRNA, and 2 independent experiments for simultaneous down-regulation performed in triplicate. t test: *P < .05, **P < .01 and ***P < .001 of the indicated silencing condition compared with control (si scramble in black; single siRNA indicated gene in blue). All data from fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis are shown in Figure 12. (A and C) To evaluate the effect of silencing of the 5 genes with outlier mutations on the proliferation and migration rate of HCT116 cell lines, real-time monitoring of (B) cell growth and (C) cell migration using the xCELLigence system was performed. With this instrument, silencing of the WNK1, HMGXB4, and GART genes was shown to attenuate cell proliferation and migration significantly, whereas silencing of PRRC2C and RFC3 did not (Figure 13). The cell index for proliferation and migration are presented as means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. Two-way analysis of variance using the Bonferroni post hoc test: *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001. (D) Expression of WNK1 or PRRC2C shRNA in CRC cells leads to decreased tumor growth. Left panels: Comparative analysis of tumor growth (mean tumor volumes) in xenografts derived from HCT116 and SW480 cell lines transfected with WNK1 or PRRC2C shRNA, respectively, and compared with cells containing a scrambled shRNA. There were 7 mice in the WNK1 group and 10 in the PRRC2C group. Data represent means ± SEM, t test: *P < .05. Middle panels: WNK1 and/or PRRC2C mRNA reverse-transcription quantitative PCR expression analysis at 2 time points (at day 0 from transfected cells before injection and at day 28 or 30 from tumor xenograft). Right panels: Macroscopic picture of xenograft before and after tumor excision from HCT116 and SW480 stably transfected cells.

Figure 11.

Validation of gene abrogation by the siRNA approach and validation of the deleterious impact of 5 outlier mutations genes in RKO, KM12, FET, and SW620 CRC cell lines. Gene expression (mRNA level) of outlier mutation–related genes after knock-down by single siRNA was assessed at (A) 24 or (B, left panel) 48 hours after transfection by real-time quantitative PCR. Data represent the means ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments. (B, right panel) Gene expression (mRNA level) of outlier mutation–related genes after simultaneous down-regulation of 3 genes in HCT116 (upper panel) and SW480 (lower panel) cell lines. (C) Gene expression (mRNA level) of outlier mutation genes after knock-down by siRNA in 4 cell lines (MSI: RKO, KM12; and microsatellite stable: FET, SW620) was assessed 48 hours after transfection by real-time quantitative PCR. Data represent the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis (Annexin V) of untreated (triangle) or TRAIL-treated (circle) MSI (RKO and KM12, left panel) and microsatellite stable (FET and SW620, right panel) CRC cell lines transfected either with a single specific siRNA gene (WNK1, HMGXB4, and/or GART) or with scrambled siRNA. Data represent the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. t test: *P < .05, **P < .01 and ***P < .001 of indicated silencing condition compared with control.

Figure 12.

Flow cytometry data. Flow cytometry analysis of early (Annexin V–positive and 7-amino-actinomycin D [7-AAD]-negative cells) and late (Annexin V– and 7-AAD–positive cells) apoptosis of untreated or TRAIL-treated HCT116 (MSI, upper panel) and SW480 (microsatellite stable, lower panel) CRC cell lines transfected either with a single specific siRNA gene (WNK1, HMGXB4, GART, RFC3, and/or PRRC2C) or with scrambled siRNA. One experiment of the 3 performed is shown.

Figure 13.

Experimental data of cell growth and cell migration analysis. Real-time monitoring of (A) cell growth and (B) cell migration using the xCELLigence system (HCT116 CRC MSI cell line). This system allows estimation of the cell index in real time—the parameter based on impedance measurement and reflecting the number of cells attached to the surface of the experimental chambers. Quadruplicates of 3 independent experiments are shown. (C) H&E stain, and WNK1 marker expression by immunohistochemistry in tumor xenografts at day 30 is shown (see Figure 10D).

Negatively Selected Events Are Associated With Worse Survival of MSI CRC Patients

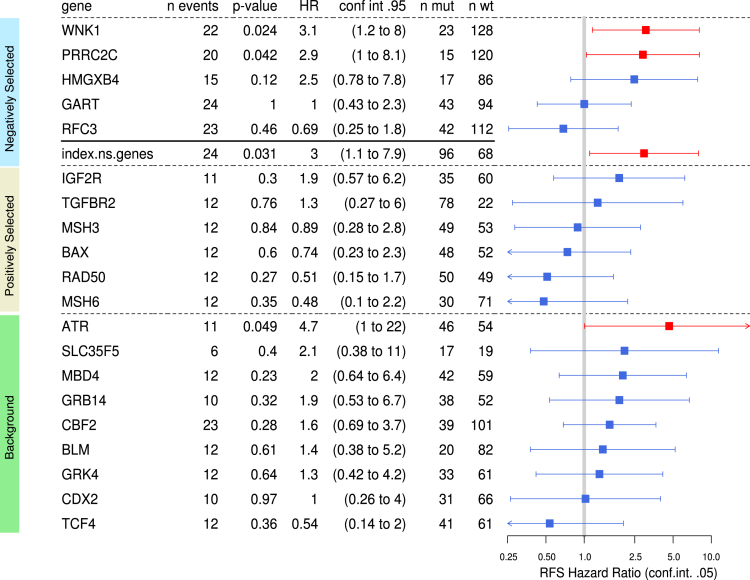

We next evaluated whether negatively selected coding sequence mutations that were associated with deleterious effects in CRC cells (eg, microsatellites located in coding regions of WNK1, HMGXB4, PRRC2C, RFC3, or GART) also may be clinically relevant. An additional cohort of 164 MSI CRC patients originating from 3 clinical centers in France was analyzed by Cox survival models adjusted for TNM stage. In the overall cohort, mutated WNK1 (hazard ratio [HR], 3.1; 95% CI, 1.2–8; P = .02) and PRRC2C (HR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1–8.1; P = .04) were associated with worse RFS (Figure 14). The HMGXB4 mutation also showed a trend for association with worse RFS (HR, 2.5; 95% CI, 0.78–7.8; P = .12) (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Clinical relevance of MSI-driven coding region mutations in target genes in CRC patients. The association of 5 negatively selected MSI-driven mutational events with RFS was calculated in the cohort of 164 MSI CRC patients with survival data available. The association of the Boolean mutational index (see the Materials and Methods section) was calculated from the mutational status of the above 5 target genes (WNK1, PRRC2C, HMGXB4, GART, RFC3) in each tumor sample (status 0, no mutation observed; status 1, at least 1 mutation observed) with RFS also is shown. Also reported is the association with RFS of a series of 15 other frequent MSI mutations (6 positively selected and 9 background events) that we investigated previously in the same MSI CRC samples and published.16 Forest plot of RFS HRs of independent univariate Cox analyses are shown. Squares represent the HRs and horizontal bars represent the 95% CIs. Red indicates a P value of less than 5% (worse prognosis) and blue indicates more than 5%.

To examine the overall relationship between the 5 negatively selected target gene mutations and patient survival, a mutational index value was computed to summarize this MSI target gene category. Cox modeling based on this representation was associated with significantly worse survival, suggesting an overall negative impact of these mutational events on patient outcome (HR, 3; 95% CI, 1.1–7.9; P = .03) (Figure 14).

Discussion

MSI tumors represent a distinctive phenotype characterized by a high background of nucleotidic instability. The present work indicates that, expectedly, in such an MMR-deficient context,8, 9, 13, 37 genomic instability generates positively selected somatic mutations in both R and NR DNA sequences that are likely to contribute to the tumorigenic process. In addition, it also suggests that MSI tumors must deal with frequent somatic mutational events that are deleterious for the MSI tumor cells and result in a tumor-suppressor effect. Among these mutational events, some should be lethal and therefore not detected in tumor DNA whereas other negatively selected could be deleterious for tumor cells without being lethal, depending on the mutational landscape and other factors. These events represent a weakness of the MSI-driven tumorigenic process. The present results shed new light on MMR-deficient tumorigenesis and suggest that genomic instability in MSI CRC plays a dual role in achieving tumor cell transformation.

Frameshift gene mutations owing to MSI in coding repeats are likely to result in inactivation of the corresponding truncated mutant protein, provided the mutant transcript is not degraded by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay.10 The clearly deleterious consequences of 5 negatively selected coding mutations we report here in both MSI and microsatellite stable tumor cells is of interest. Their frequent somatic inactivation in MSI CRC can impede the progress of cell transformation and lead to the regression of clones in which they occur. A major example of this was WNK1, which codes for a positive regulator of canonical Wnt/-catenin signaling and whose inactivation in different tumor types is deleterious,38, 39 other mutations occurring in HMGXB4, GART,40, 41 RFC3,42, 43 or PRRC2C, and the silencing of this latter candidate decreased cell proliferation in lung cancer.44 In line with our results, a recent study also found that silencing of some of these targets (WNK1, RFC3, and GART) was lethal in haploid human tumor cells.45 Although the MMR-deficient tumor cells in which these mutations occurred were eliminated from the bulk of most MSI colon tumors through negative selection, our results also showed that, strikingly, the few tumors in which at least one of these mutations was detected was associated with worse patient prognosis. This suggests the anticancer impact of such mutations should be counterbalanced by other oncogenic processes that remain to be identified and were responsible for the poor prognosis. This clinical observation on patient outcome is intriguing and will require further investigation in larger cohorts. It was difficult to address with the present cohort because of the low frequencies of negatively selected events and the small number of relapses in MSI CRC patients.

Aside from the small number of deleterious mutations found in coding sequences, negatively selected mutational events were found mostly in long noncoding repeats located in the 5’ or 3’ UTR. Although approximately 10% of these somatic mutations were found to alter gene expression at the RNA level, their possible functional impact requires further investigation. We did not perform a functional analysis to show a deleterious impact in MSI CRC cells, as performed for negatively selected events in coding regions. However, these outlier mutations were located in genes with a role in several cancer-related processes, as shown in the pathway enrichment analysis. This indicates their negative selection in MSI CRC cells was not a chance event. Interestingly, some of the negatively selected mutations identified here were found to up-regulate tumor-suppressor functions during MSI tumor development, whereas others were observed to down-regulate oncogene functions. This is in accordance with their paradoxical activation or inactivation, respectively, during the tumorigenic process. Together, these findings highlight that MSI in noncoding UTRs could have an important antitumor impact during MMR-deficient tumor development.

Our analysis of the MSI colon tumor exome confirmed the majority of known target gene mutations for MSI. These and many other mutations in 8- to 10-bp repeats reported previously in the literature are thought to be key events in MSI-driven tumorigenesis (for review see Hamelin et al37). Although these mutations may have functional significance in particular contexts, we showed that the frequency of most of these microsatellite mutations was not different from the background frequency expected for their length, suggesting their overall impact on tumor development may be limited, if any. In contrast, we identified several mutations in smaller coding and noncoding DNA repeats of 5–7 bp in length that showed a high positive selection in MSI CRC. We postulate these new candidate genes for MSI tumor progression that contain relatively short repeats represent important oncogenic driver events in MMR-deficient CRC and may be much more relevant for tumorigenesis than many of the MSI-related mutations reported in the past.

Although almost all sporadic MSI CRC arise because of MLH1 deficiency after epigenetic silencing, Lynch-related MSI CRC is associated with germline mutations in MLH1 (45% of cases), MSH2 (45%), MSH6 (∼10%), or PMS2 (∼1%). Although MLH1- and MSH2-deficient MSI tumors show similar levels of nucleotide instability, including overall MSI as confirmed here, significantly lower mutation frequencies of R and NR sequences are observed in MSH6- and PMS2-deficient MSI tumors. The present cohort was designed to investigate the most common MMR-deficient genotypes in CRC (ie, MLH1- and MSH2-deficient tumors). Only 1 MSH6-deficient CRC was included, as mentioned. Future studies could aim to analyze genomic instability in the rare MSI CRC showing MSH6 or PMS2 deficiency that could show a lower mutation burden at both R and NR sequences.

There is no contradiction between the findings of this study and the literature in the field. Recent data obtained from analysis of thousands of tumors from different primary sites show that, unlike species evolution, positive selection outweighs the negative selection of somatic mutational events during tumor progression. However, these investigations were concerned with alterations at NR sequences and did not take into account mutations in R sequences. In contrast, R sequences (microsatellites) have very high physiopathologic relevance in the tumor model investigated in the present study, namely MSI tumors. We did not observe negative selection of NR sequences in MSI CRC, in line with the prevailing dogma. However, our results show the existence of both positive and negative selection of R sequences during tumor progression, as well as highlighting the dual role for MSI in this important tumor model.

The limitations of our work relate mainly to the analysis of a limited series of MSI CRC using WES, even if it represents a large series of such tumors investigated by this approach. Further studies are required to confirm our results using larger cohorts of MSI CRC, thus allowing the identification of a more robust signature of target genes for MSI that undergo positive or negative selection. Important pro- and anti-cancer genes for MSI tumorigenesis are likely to be included in these genomic signatures. The pathophysiological relevance and opposing functional effects of such MSI-driven events should allow major advances in the understanding of MSI tumorigenesis and in the development of personalized treatments for patients with MMR-deficient tumors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Barry Iacopetta for critical reading of the manuscript. The present work has benefited from the animal facility of Saint-Antoine Research Center (PHEA, Mrs Tatiana Ledent), and the core facility of UMS30-LUMIC, CISA (Cytometry and Imagery Saint Antoine, Mrs Annie Munier), Sorbonne University, UPMC Univ Paris 06, INSERM, Saint-Antoine (CRSA), F-75012 Paris, France.

Footnotes

Author contributions Alex Duval, Ada Collura, Aurélien de Reyniès, Anastasia Goloudina, Laetitia Marisa, and Vincent Jonchere were responsible for the study conceptualization; Agathe Guilloux, Aurélien de Reyniès, Laetitia Marisa, Vincent Jonchere, Alex Duval, Alain Virouleau, and Ada Collura were responsible for the methodology; Ada Collura, Malorie Greene, Olivier Buhard, Romane Bertrand, Magali Svrcek, Samuel Landman, Toky Ratovomanana, Pascale Cervera, Alex Duval, Jérémie H. Lefèvre, Erell Guillerm, Florence Coulet, Mira Ayadi, Thierry André, Jean-François Fléjou, Lucile Armenoult, Sylvie Job, Fatiha Merabtene, Sylvie Dumont, Yann Parc, and Nabila Elarouci performed the investigation; Alex Duval, Vincent Jonchere, Laetitia Marisa, Ada Collura, Agathe Guilloux, and Aurélien de Reyniès wrote the original draft; and Alex Duval was responsible for supervision.

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding This work was supported by grants Institut National Du Cancer, Programme de Recherche Translationnelle en Cancérologie “MicroSplicoter”, sites de recherche intégrée sur le cancer (SIRIC) and Heterogeneity of Tumors & Ecosystem (HTECoLi) from the Institut National du Cancer (A.D.), the Fondation Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (A.C.), and the Canceropole Ile de France (A.C.). This work is part of the Cartes d’Identité des Tumeurs research program, which was funded and developed by the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greaves M., Maley C.C. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481:306–313. doi: 10.1038/nature10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martincorena I., Raine K.M., Gerstung M., Dawson K.J., Haase K., Van Loo P., Davies H., Stratton M.R., Campbell P.J. Universal patterns of selection in cancer and somatic tissues. Cell. 2017;171:1029–1041 e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakhoum S.F., Landau D.A. Cancer evolution: no room for negative selection. Cell. 2017;171:987–989. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leach F.S., Nicolaides N.C., Papadopoulos N., Liu B., Jen J., Parsons R., Peltomaki P., Sistonen P., Aaltonen L.A., Nystrom-Lahti M., Zhang G.J., Meltzer P.S., Yu J.W., Kao F.T., Chen D.J., Cerosaletti K.M., Fournier R.E.K., Todd S., Lewis T., Leach R.J., Naylor S.L., Weissenbach J., Mecklin J.P., Jarvinen H., Petersen G.M., Hamilton S.R., Green J., Jass J., Watson P., Lynch H.T., Trent J.M., de la Chapelle A., Kinzler K.W., Vogelstein B. Mutations of a mutS homolog in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cell. 1993;75:1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90330-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thibodeau S.N., Bren G., Schaid D. Microsatellite instability in cancer of the proximal colon. Science. 1993;260:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.8484122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ionov Y., Peinado M.A., Malkhosyan S., Shibata D., Perucho M. Ubiquitous somatic mutations in simple repeated sequences reveal a new mechanism for colonic carcinogenesis. Nature. 1993;363:558–561. doi: 10.1038/363558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortes-Ciriano I., Lee S., Park W.Y., Kim T.M., Park P.J. A molecular portrait of microsatellite instability across multiple cancers. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15180. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hause R.J., Pritchard C.C., Shendure J., Salipante S.J. Classification and characterization of microsatellite instability across 18 cancer types. Nat Med. 2016;22:1342–1350. doi: 10.1038/nm.4191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duval A., Hamelin R. Mutations at coding repeat sequences in mismatch repair-deficient human cancers: toward a new concept of target genes for instability. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2447–2454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliveira C., Pinto M., Duval A., Brennetot C., Domingo E., Espin E., Armengol M., Yamamoto H., Hamelin R., Seruca R., Schwartz S., Jr. BRAF mutations characterize colon but not gastric cancer with mismatch repair deficiency. Oncogene. 2003;22:9192–9196. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim T.M., Laird P.W., Park P.J. The landscape of microsatellite instability in colorectal and endometrial cancer genomes. Cell. 2013;155:858–868. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duval A., Reperant M., Compoint A., Seruca R., Ranzani G.N., Iacopetta B., Hamelin R. Target gene mutation profile differs between gastrointestinal and endometrial tumors with mismatch repair deficiency. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1609–1612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woerner S.M., Yuan Y.P., Benner A., Korff S., von Knebel Doeberitz M., Bork P. SelTarbase, a database of human mononucleotide-microsatellite mutations and their potential impact to tumorigenesis and immunology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D682–D689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dorard C., de Thonel A., Collura A., Marisa L., Svrcek M., Lagrange A., Jego G., Wanherdrick K., Joly A.L., Buhard O., Gobbo J., Penard-Lacronique V., Zouali H., Tubacher E., Kirzin S., Selves J., Milano G., Etienne-Grimaldi M.C., Bengrine-Lefevre L., Louvet C., Tournigand C., Lefevre J.H., Parc Y., Tiret E., Flejou J.F., Gaub M.P., Garrido C., Duval A. Expression of a mutant HSP110 sensitizes colorectal cancer cells to chemotherapy and improves disease prognosis. Nat Med. 2011;17:1283–1289. doi: 10.1038/nm.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collura A., Lagrange A., Svrcek M., Marisa L., Buhard O., Guilloux A., Wanherdrick K., Dorard C., Taieb A., Saget A., Loh M., Soong R., Zeps N., Platell C., Mews A., Iacopetta B., De Thonel A., Seigneuric R., Marcion G., Chapusot C., Lepage C., Bouvier A.M., Gaub M.P., Milano G., Selves J., Senet P., Delarue P., Arzouk H., Lacoste C., Coquelle A., Bengrine-Lefevre L., Tournigand C., Lefevre J.H., Parc Y., Biard D.S., Flejou J.F., Garrido C., Duval A. Patients with colorectal tumors with microsatellite instability and large deletions in HSP110 T17 have improved response to 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:401–411 e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berthenet K., Boudesco C., Collura A., Svrcek M., Richaud S., Hammann A., Causse S., Yousfi N., Wanherdrick K., Duplomb L., Duval A., Garrido C., Jego G. Extracellular HSP110 skews macrophage polarization in colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1170264. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1170264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berthenet K., Bokhari A., Lagrange A., Marcion G., Boudesco C., Causse S., De Thonel A., Svrcek M., Goloudina A.R., Dumont S., Hammann A., Biard D.S., Demidov O.N., Seigneuric R., Duval A., Collura A., Jego G., Garrido C. HSP110 promotes colorectal cancer growth through STAT3 activation. Oncogene. 2017;36:2328–2336. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sagher D., Hsu A., Strauss B. Stabilization of the intermediate in frameshift mutation. Mutat Res. 1999;423:73–77. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duval A., Rolland S., Compoint A., Tubacher E., Iacopetta B., Thomas G., Hamelin R. Evolution of instability at coding and non-coding repeat sequences in human MSI-H colorectal cancers. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:513–518. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto H., Imai K. Microsatellite instability: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2015;89:899–921. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondelin J., Gylfe A.E., Lundgren S., Tanskanen T., Hamberg J., Aavikko M., Palin K., Ristolainen H., Katainen R., Kaasinen E., Taipale M., Taipale J., Renkonen-Sinisalo L., Jarvinen H., Bohm J., Mecklin J.P., Vahteristo P., Tuupanen S., Aaltonen L.A., Pitkanen E. Comprehensive evaluation of protein coding mononucleotide microsatellites in microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:4078–4088. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marisa L., de Reynies A., Duval A., Selves J., Gaub M.P., Vescovo L., Etienne-Grimaldi M.C., Schiappa R., Guenot D., Ayadi M., Kirzin S., Chazal M., Flejou J.F., Benchimol D., Berger A., Lagarde A., Pencreach E., Piard F., Elias D., Parc Y., Olschwang S., Milano G., Laurent-Puig P., Boige V. Gene expression classification of colon cancer into molecular subtypes: characterization, validation, and prognostic value. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assie G., Letouze E., Fassnacht M., Jouinot A., Luscap W., Barreau O., Omeiri H., Rodriguez S., Perlemoine K., Rene-Corail F., Elarouci N., Sbiera S., Kroiss M., Allolio B., Waldmann J., Quinkler M., Mannelli M., Mantero F., Papathomas T., De Krijger R., Tabarin A., Kerlan V., Baudin E., Tissier F., Dousset B., Groussin L., Amar L., Clauser E., Bertagna X., Ragazzon B., Beuschlein F., Libe R., de Reynies A., Bertherat J. Integrated genomic characterization of adrenocortical carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:607–612. doi: 10.1038/ng.2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niu B., Ye K., Zhang Q., Lu C., Xie M., McLellan M.D., Wendl M.C., Ding L. MSIsensor: microsatellite instability detection using paired tumor-normal sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1015–1016. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams D.A. Extra binomial variation in logistic linear models. Appl Statist. 1982;31:144–148. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tibshirani J., Manning C.D. Robust logistic regression using shift parameters. ACL. 2014;2:124–129. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bertsekas D.P. Incremental proximal methods for large scale convex optimization. Math Program. 2011;129:163. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCullagh P., Nelder J.A. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1989. Generalized linear models; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang da W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biard D.S., Despras E., Sarasin A., Angulo J.F. Development of new EBV-based vectors for stable expression of small interfering RNA to mimick human syndromes: application to NER gene silencing. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:519–529. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boland C.R., Thibodeau S.N., Hamilton S.R., Sidransky D., Eshleman J.R., Burt R.W., Meltzer S.J., Rodriguez-Bigas M.A., Fodde R., Ranzani G.N., Srivastava S. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Microsatellite Instability for cancer detection and familial predisposition: development of international criteria for the determination of microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5248–5257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buhard O., Cattaneo F., Wong Y.F., Yim S.F., Friedman E., Flejou J.F., Duval A., Hamelin R. Multipopulation analysis of polymorphisms in five mononucleotide repeats used to determine the microsatellite instability status of human tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:241–251. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexandrov L.B., Nik-Zainal S., Wedge D.C., Aparicio S.A., Behjati S., Biankin A.V., Bignell G.R., Bolli N., Borg A., Borresen-Dale A.L., Boyault S., Burkhardt B., Butler A.P., Caldas C., Davies H.R., Desmedt C., Eils R., Eyfjord J.E., Foekens J.A., Greaves M., Hosoda F., Hutter B., Ilicic T., Imbeaud S., Imielinski M., Jager N., Jones D.T., Jones D., Knappskog S., Kool M., Lakhani S.R., Lopez-Otin C., Martin S., Munshi N.C., Nakamura H., Northcott P.A., Pajic M., Papaemmanuil E., Paradiso A., Pearson J.V., Puente X.S., Raine K., Ramakrishna M., Richardson A.L., Richter J., Rosenstiel P., Schlesner M., Schumacher T.N., Span P.N., Teague J.W., Totoki Y., Tutt A.N., Valdes-Mas R., van Buuren M.M., van't Veer L., Vincent-Salomon A., Waddell N., Yates L.R., Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome I, Consortium I.B.C., Consortium I.M.-S., PedBrain I., Zucman-Rossi J., Futreal P.A., McDermott U., Lichter P., Meyerson M., Grimmond S.M., Siebert R., Campo E., Shibata T., Pfister S.M., Campbell P.J., Stratton M.R. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500:415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogelstein B., Papadopoulos N., Velculescu V.E., Zhou S., Diaz L.A., Jr., Kinzler K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El-Bchiri J., Buhard O., Penard-Lacronique V., Thomas G., Hamelin R., Duval A. Differential nonsense mediated decay of mutated mRNAs in mismatch repair deficient colorectal cancers. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2435–2442. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamelin R., Chalastanis A., Colas C., El Bchiri J., Mercier D., Schreurs A.S., Simon V., Svrcek M., Zaanan A., Borie C., Buhard O., Capel E., Zouali H., Praz F., Muleris M., Flejou J.F., Duval A. [Clinical and molecular consequences of microsatellite instability in human cancers] Bull Cancer. 2008;95:121–132. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2008.0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodan A.R., Jenny A. WNK kinases in development and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2017;123:1–47. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serysheva E., Mlodzik M., Jenny A. WNKs in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:173–174. doi: 10.4161/cc.27038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cong X., Lu C., Huang X., Yang D., Cui X., Cai J., Lv L., He S., Zhang Y., Ni R. Increased expression of glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase is associated with a poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma, and it promotes liver cancer cell proliferation. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:1370–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu X., Ding Z., Liu Y., Zhang J., Liu F., Wang X., He X., Cui G., Wang D. Glycinamide ribonucleotide formyl transferase is frequently overexpressed in glioma and critically regulates the proliferation of glioma cells. Pathol Res Pract. 2014;210:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.He Z.Y., Wu S.G., Peng F., Zhang Q., Luo Y., Chen M., Bao Y. Up-Regulation of RFC3 promotes triple negative breast cancer metastasis and is associated with poor prognosis via EMT. Transl Oncol. 2017;10:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen H., Cai M., Zhao S., Wang H., Li M., Yao S., Jiang N. Overexpression of RFC3 is correlated with ovarian tumor development and poor prognosis. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:10259–10266. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2216-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]