Abstract

A catalytic method to prepare highly substituted 1,3-dienes from two different alkenes is described using a directed, palladium(II)-mediated C(alkenyl)–H activation strategy. The transformation exhibits broad scope across three synthetically useful substrate classes masked with suitable bidentate auxiliaries (4-pentenoic acids, allylic alcohols, and bishomoallylic amines) and tolerates internal non-conjugated alkenes, which have traditionally been a challenging class of substrates in this type of chemistry. Catalytic turnover is enabled by either MnO2 as the stoichiometric oxidant or by co-catalytic Co(OAc)2 and O2 (1 atm). Experimental and computational studies were performed to elucidate the preference for C(alkenyl)–H activation over other potential pathways. As part of this effort, a structurally unique alkenylpalladium(II) dimer was isolated and characterized.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The selective synthesis and functionalization of alkenes is a central theme in organic chemistry. Our laboratory has recently developed a series of substrate-directed palladium(II)-catalyzed alkene hydrofunctionalization and 1,2-difunctionalization reactions (Scheme 1A).1 These reactions employ removable bidentate directing groups to facilitate π-Lewis acid activation of the proximal alkene for nucleopalladation. Given that this family of directing groups also promotes C(sp2)–H and C(sp3)–H activation,2,3 we questioned whether it would be possible to achieve selective C(alkenyl)–H functionalization within these synthetically versatile alkene substrate classes (Scheme 1B). In terms of synthetic strategy, the proposed mode of reactivity would offer expedient access to highly substituted alkene products and would complement directed alkene 1,2-difunctionalization chemistry.

Scheme 1.

Approaches to directed alkene functionalization

Compared to C(alkyl)–H and C(aryl)–H activation, C(alkenyl)–H activation has been less thoroughly explored.4 C(alkenyl)–H functionalization reactions are complicated by competitive reactivity of the alkene moiety, which can make chemoselectivity a significant challenge. Additionally, site selectivity can be difficult to control due to the presence of alternative C–H cleavage sites (e.g. C(allylic)–H activation). Such issues are particularly problematic in C–H activation of internal di- or tri-alkyl substituted alkenes.

Oxidative coupling of C(alkenyl)–H bonds with alkenes represents an attractive approach to access 1,3-dienes and polyene motifs, which are important synthetic targets due to their presence in natural products, their utility in [4+2] cycloaddition reactions, and their unique materials properties. At present, the most common methods for accessing these targets include the Wittig/Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reactions5 or transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions.6 While robust, these routes possess disadvantages in that they require prefunctionalized starting materials, generate stoichiometric byproducts, and in some cases deliver E/Z product mixtures. Several previous reports have described palladium(II)-catalyzed C(alkenyl)–H alkenylation, with the vast majority of examples employing conjugated alkenes, such as styrenes7 acrylates/acrylamides,8 enamides,9 and enol esters/ethers10. Despite the synthetic utility of expanding this reactivity toward non-conjugated alkenes, reports of such a transformation are rare. Notably, the Gusevskaya group developed a camphene dimerization reaction11 and Loh and coworkers employed an alcohol or silyl ether directing group to achieve C(alkenyl)–H activation of 1,1-disubstituted non-conjugated terminal alkenes.12 During the preparation of this manuscript, Chou and co-workers reported a carboxylate-directed C(alkenyl)–H alkenylation of 1,4-cyclohexadiene compounds, which undergo decarboxylative rearomatization in situ.13 In the present study, we report a method for preparing 1,3-dienes starting from a directing-group-containing alkene (4-pentenoic acid, allyl alcohol, or 4-pentenamine derivative) and an electron-poor alkene coupling partners. The reaction involves a directed C(alkenyl)–H activation step4 which is highly selective for the C(alkenyl)–H bond via a six-membered palladacycle intermediate (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Substrate scope (allylic alcohols bishomoallylic amines)a.

a Reaction conditions were as in Table1, entry 1 unless otherwise statated. b 20 mol% Pd(OAc)2

Results and Discussion

1. Reaction optimization

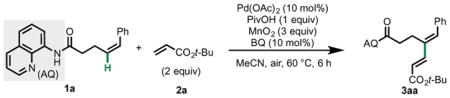

We commenced this investigation by surveying reaction conditions using (Z)-5-phenyl-4-pentenamide 1a bearing Daugulis’s 8-aminoquinoline (AQ) directing group2,3 as the model substrate and tert-butylacrylate 2a as the coupling partner (Table 1).14 We found that in the presence of Pd(OAc)2 γ-C(alkenyl)–H activation via a six-membered palladacycle took place selectively; the other potential products from β-C(allylic)–H activation via a five-membered palladacycle/π-allyl intermediate or δ-C(alkenyl)–H activation via a seven-membered palladacycle were not observed (vide infra). Extensive optimization revealed that a carboxylic acid promoter was beneficial, and among those tested, pivalic acid was found to be optimal. Achieving efficient reoxidation in this catalytic cycle proved to be highly challenging. Ultimately, we identified two effective oxidation systems. First, it was found that a combination of a catalytic amount of benzoquinone (BQ) and 3 equiv MnO2 gave both high conversion and good material balance.15 Second, by substituting MnO2 with 10 mol% Co(OAc)2 and running the reaction under an O2 atmosphere (1 atm), equivalently high yield was also observed (Table 1, entries 19 and 20). We envisioned that both conditions could be useful to end-users depending on the setting, so both were explored further (vide infra). Although the reaction occurred at room temperature (90% isolated yield after 6 d using MnO2), we elected to conduct the substrate scope on 60 °C and 6 h because of the convenient reaction temperature and time (Table 2). Control experiments confirmed that palladium is required (Table 1, entries 16–18).

Table 1.

Optimization of conditions

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Variation from Standard Conditions | Yielda | Entry | Variation from Standard Conditions | Yielda |

| 1 | none | (97%) | 11 | DMA | 29% |

| 2 | HOAc | 65% | 12 | HFIP | 16% |

| 3 | benzoic acid | 41% | 13 | MnO2 (1 equiv)b | 57% |

| 4 | 1-AdaCO2H | 46% | 14 | MnO2 (2 equiv)b | 76% |

| 5 | squaric acid | 44% | 15 | no BQb | 39% |

| 6 | PdCl2 | 10% | 16 | no Pd(OAc)2 | 0% |

| 7 | PdBr2 | 11% | 17 | Mn(OAc)2 (1 equiv) instead of [Pd] | 0% |

| 8 | Pd(OTFA)2 | 38% | 18 | Mn(OAc)3·H2O (1 equiv) instead of [Pd] | 0% |

| 9 | toluene | 8% | 19 | Co(OAc)2 (10 mol%) + O2, 6 h | 78% |

| 10 | THF | 47% | 20 | Co(OAc)2 (10 mol%) + O2,10 h | (97%) |

1H NMR yield using CH2Br2 as internal standard. Isolated yields in parentheses.

1:1 MeCN:toluene.

Table 2.

Substrate scope (4-pentenoic acids)

12 h.

Z:E = 1:1 before purification and 7:1 after purification.

6% of an unknown impurity.

12 h, 20 mol% Pd(OAc)2, MeCN:toluene 1:1

2. Substrate scope

We examined the substrate scope with respect to 4-pentenoic acid structure, first using MnO2 as the oxidant (Table 2).16 Different substituents on the aryl ring were examined, and a variety of electron-donating and -withdrawing groups were found to be well tolerated (3aa–3ka). Additionally, steric bulk at the ortho position (3da) did not hamper the reaction. Electron-rich heterocycles were tolerated in the reaction (3ha–3ka). Furthermore, 1,3-diene and 1,3-enyne substrates reacted with exquisite site selectivity, offering expedient access to highly conjugated products 3la and 3ma. The reaction was highly sensitive to the E/Z-configuration of the alkene starting material as the corresponding E-phenyl substrate was unreactive, presumably due to steric repulsion in the C–H activation step (see SI). In addition to aryl groups on the alkene, Z-alkyl groups, such as methyl, ethyl, cyclopropyl, tert-butyl, and benzyl, provided moderate to high yields (3na–3ra). In some case E/Z isomerization was observed (3na–3pa and 3ra) (vide infra).17 A large-scale reaction was performed with 2.8 mmol of Z-methyl substrate 1n, and the yield of 3na was essentially identical to that of the small-scale trial, illustrating the preparative utility of this method. Introducing substituents on either of the methylene carbon atoms between the alkene and the carbonyl group led to attenuated reactivity, and these substrates required harsher conditions (3ua–3wa). Groups α to the carbonyl (3va) had a more significant effect in suppressing product formation compared to groups β to the carbonyl group (3ua).

Apart from 4-pentenamide substrates, other substrate classes were also compatible with this reaction using different directing groups (Figure 1). Allylic alcohols masked as their AQ-carbamates (Table 3) could be functionalized with this method (5aa and 5ba). With bishomoallylic amine substrates (i.e., 4-pentenamines) (Table 3), we found that Daugulis’s picolinamide directing group2,3 facilitated analogous C(alkenyl)–H olefination in moderate to good yields (7aa–7ca). Interestingly, the endo alkenyl C–H bond was activated at 60 °C (7ca) while the exo C–H bond (7ca′) could be subsequently activated at elevated temperature via a seven-membered palladacycle.

Table 3.

Coupling partner scope

|

12 h.

Next, we proceeded to test the scope of alkene coupling partners using 1a as the model reactant (Table 4). Several different electron-deficient alkenes reacted in moderate to good yields (3ab–3ah). In particular, vinylsulfonylfluoride (3ac), which to our knowledge has not previously been used in C–H alkenylation, was successfully incorporated with high yield.18 In the case of acrylonitrile (2h), the minor Z alkene isomer (Z-3ai) was also formed. When methyl methacrylate (2g) was employed in the reaction, the regioselectivity of β-hydride elimination was found to differ from the other examples, giving the non-conjugated 1,4-diene as the major product. Non-conjugated alkenes were generally ineffective; however, allyl acetate was an exception. Interestingly, in this case, β-H elimination (3ai) was found to be competitive with β-OAc elimination, which leads to allylation product (3ai′).

Table 4.

Optimization of tandem E/Z isomerization/C(alkenyl)–H alkenylation

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Variation from Standard Conditions | Yielda | Z:Ea |

| 1 | none | (65%) | 6.4:1 |

| 2b | room temperature | 25% | 4.5:1 |

| 3b | 40 °C | 71% | 4.1:1 |

| 4b | 50 °C | 63% | 4:1 |

| 5c | PdCl2 | 9% | 3.3:1 |

| 6c | Pd(OTFA)2 (10 mol%) | 20% | 2.9:1 |

| 7c | Pd(acac)2 (10 mol%) | 30% | 3.7:1 |

| 8c | White catalyst (10 mol%) | 20% | 2:1 |

| 9d | Pd(OAc)2(10 mol%) | 51% | 3.3:1 |

1H NMR yield using CH2Br2 as internal standard. Isolated yields in parentheses.

PivOH, 16 h.

PivOH, 60 °C, 19 h.

PivOH, 60 °C, 6 h.

With vinyl ketones (2j and 2k), a different reaction outcome was observed (eq. 1). In this case, a formal Michael-type 1,4-conjugate addition19 took place (3aj and 3ak), and the reactions did not require exogenous oxidant, consistent with being redox-neutral. We speculate that in this case the more strongly electron-withdrawing ketone leads to an O-bound palladium enolate, which is prone to protodepalladation under the reaction conditions (eq. 1).

|

(1) |

3. Aerobic redoxidation

The method above using stoichiometric MnO2 as oxidant is straightforward and operationally convenient, as it does not require use of a compressed gas, special safety considerations, or dedicated equipment. Nevertheless, it has the disadvantage of generating stoichiometric manganese waste. Thus, in line with goals of sustainable synthesis, we also sought to probe the scope of the alternative reaction conditions using catalytic Co(OAc)2 as an electron transfer mediator under O2 atmosphere (Scheme 2).20 Three representative substrates (1a, 1k and 1n) were tested and delivered the desired products in essentially identical yields to the stoichiometric MnO2 conditions. In this case, the only stoichiometric waste generated during the course of the reaction is H2O. These results demonstrate that either method can be used depending on the goals of the end-user.

Scheme 2.

Aerobic reoxidation system

4. Tandem E/Z isomerization/C(alkenyl)–H alkenylation

As mentioned above, alkyl-substituted internal alkenes underwent isomerization under the reaction conditions prior to reacting (see SI). Though a detailed investigation of the mechanism of E/Z-isomerization in this case is outside of the scope of the present work, three possibilities based on previous studies21–24 of this general phenomenon include (1) π-allylpalladium(II) formation, (2) nucleometalation/β-X elimination, and (3) π-Lewis acid activation to form a secondary carbocation that is susceptible to isomerization. Irrespective of the mechanism, we reasoned that this process could be harnessed to accomplish a productive reaction.24 Because E-substituted alkenes are far less reactive, we considered whether we could potentially carry out an in situ E/Z-isomerization and selectively react the Z-isomer via C–H alkenylation (Scheme 3). This strategy would offer the possibility of carrying out dynamic kinetic resolution of E/Z-alkene mixtures. This reaction system requires that the palladium(II) catalyst perform two distinct tasks, E/Z isomerization and C(alkenyl)–H alkenylation with appropriate rates. Hence, we surmised that judicious selection of reaction conditions would be required. To test this idea, we selected E-1n as the model substrate and optimized reaction conditions (Table 5) to maximize yield and Z/E ratio. Different palladium catalysts were screened,25 and Pd(OAc)2 performed the best (entries 5–8). Temperature was observed to dramatically influence the stereoselectivity of this reaction (entries 2–4), the highest selectivity being reached at 40 °C. The choice of carboxylic acid was also found to play an important role in controlling yield and selectivity. In contrast to aliphatic acids, certain aromatic carboxylic acids were more successful in promoting this isomerization. Neither electron-rich nor electron-poor aromatic carboxylic acids were compatible; however, naphthoic acid was found to be optimal. Under these conditions, 3na′ was obtained in 65% yield with 6.4 Z/E selectivity from pure E-1n. Control experiments (see SI) confirmed the presence of the Z-isomer of the starting material (Z-1n) under the reaction conditions and ruled out the alternative pathway whereby E-1n is first C–H functionalized to E-3na′, which is then selectively isomerized to Z-3na (which in this mechanism would be assumed to be the thermodynamically favored product).

Scheme 3.

Proposed tandem E/Z/isomerization/C–H activation

5. Directing group removal

The directing group could be conveniently removed under Ohshima’s recently reported nickel-catalyzed methanolysis conditions,26 providing 75% yield with only slight erosion of Z/E stereochemistry (eq. 2). This result further establishes the utility of this method in preparative synthetic chemistry.

|

(2) |

6. Mechanistic studies

The high levels of site selectivity for the γ-C(alkenyl)–H bond prompted us to investigate the reaction mechanism using a combination of different techniques. First, we prepared two organopalladium intermediates relevant to the catalytic cycle, π-alkene complex 9 and alkenylpalladium(II) dimer 10, by combining stoichiometric quantities of Pd(OAc)2 with two different alkenes and carboxylic acid additives. Complex 9 is a ring-expanded analog of previously reported structures.1a,b Complex 10 is a six-membered palladacycle as anticipated; however the dimeric structure is notable, as alkenylpalladium(II) dimer motif has not been previously reported to the best of our knowledge.27 Interestingly, the distance between the two alkenyl carbons of each monomers is only 1.55 Å, which is in the range of that of a typical C–C bond. Both 9 and 10 were found to be catalytically competent in the reaction (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of organopalladium complexes 9 and 10.

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

Complex 9 promotes the reaction with similar reactivity to that of Pd(OAc)2 (eq. 3), suggesting rapid dissociation of alkene E-1n under the reaction conditions. Interestingly, in this case, isomerization of E-1n was not detected under the reaction conditions. Complex 10 was less reactive than Pd(OAc)2 (eq. 4), requiring 22 h to reach completion, which suggests that it could be a resting state in the catalytic cycle. Presumably, complex 10 first disaggregates, then the monomeric palladacycles react with the electron-poor alkene coupling partner to initiate the reaction, as both 1aa and 3qa were isolated from the crude reaction mixture.

Next, to interrogate whether C–H activation was possible at other reaction sites, we performed an H/D exchange experiment (eq. 5). Terminal alkene substrate 1t was subjected to the reaction conditions in the absence of the electron-poor alkene coupling partner using acetic acid-d4. In the experiment, 9% deuterium substitution was observed at the γ-C(alkenyl)–H bond.

|

(5) |

Deuterium incorporation could not be detected at the other positions. This result rules out a scenario in which other C–H activation pathways, such as five-membered C(allylic)–H cleavage to form the corresponding π-allyl,28 are operative under the reaction conditions but lead to intermediates that are not competent in downstream steps.

7. Computational studies

Lastly, we performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to further probe the reaction coordinate using 1t as the model substrate (Figure 2). First, three possible C–H metalation pathways from π-alkene complex 11 were examined to reveal the origin of site-selectivity (Figure 3, see SI for details). The carboxylate-assisted concerted metalation-deprotonation (CMD) of the γ-C(alkenyl)–H (TS1) has an activation free energy of 25.7 kcal/mol, with respect to the π-alkene complex 11, lower than those of the β-C(allylic) –H (TS2) and δ-C(alkenyl)–H (TS3) metalation pathways (27.5 and 31.1 kcal/mol, respectively29). This indicates the formation of the six-membered palladacycle is kinetically favored, consistent with the experimental selectivity for the γ-C(alkenyl) – H bond. The γ-C(alkenyl)–H metalation is promoted by the pre-organization of the π-alkene complex (11), which orients the highlighted γ-C(alkenyl)–H bond co-planar with the acetate and therefore decreases the distortion of the C–H bond in the CMD transition state (TS1).30 In addition, TS1 is stabilized by the stronger alkene coordination that maximizes the favorable d → π* interactions in the metalation transition state.31

Figure 2.

Computed energy profile for the formation of 1,3-diene via the γ-C(alkenyl)–H activation of 4-pentenamide substrate

Figure 3.

Computed (A) energy profiles and (B) transition states for 5-, 6-, and 7-membered pathways for C–H metalation

The coordination of the electron-deficient alkene to the six-membered palladacycle followed by 2,1-migratory insertion and β-hydride elimination was modeled next using methyl acrylate (2l) as the coupling partner. The activation energies for the migratory insertion (TS4) and β-hydride elimination (TS5) steps are lower than that of TS1, indicating γ-C(alkenyl)–H metalation is the rate- and selectivity-determining step of the reaction.

A plausible catalytic cycle for this reaction is shown in Scheme 5. Following substrate coordination to give a π-alkene palladium complex (as in 11), γ-C(alkenyl)–H activation takes place to generate the six-membered palladacycle (as in dimer 10). Coordination of the electron-deficient alkene, followed by 2,1-migratory insertion, β-H elimination, and reoxidation of the catalyst then closes the cycle.

Scheme 5.

Proposed catalytic cycle

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a catalytic method to synthesize 1,3-dienes via directed site-selective C(alkenyl)–H activation. A broad array of substrates and coupling partners are tolerated in this reaction. In order meet the needs and preferences of potential end-users, two separate conditions for reoxidation have been demonstrated, using stoichiometric oxidant (MnO2) or O2 and catalytic Co(OAc)2. The transformation can be performed on gram scale, and the amide auxiliary can be conveniently removed. Through mechanistic studies, we have characterized key intermediates in the catalytic cycle and elucidated factors relevant to the key C(alkenyl)–H activation step. We anticipate that this method and the underlying mechanistic insights will stimulate interest in developing synthetically enabling C(alkenyl)–H activation methods to expand the alkene synthesis toolkit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI), Pfizer, Inc., the National Institutes of Health (1R35GM125052), and the NSF (CHE-1654122). We gratefully acknowledge the Nankai University College of Chemistry for an International Research Scholarship (P.Y.). We thank Prof. Arnold L. Rheingold and Dr. Curtis E. Moore (UCSD) for X-ray crystallographic analysis, Dr. Jason S. Chen for assistance with prep-LC purification and Mr. David E. Hill for GC-FID analysis. We appreciate Mr. Zhen Liu and Mr. Joseph Derosa for proof reading and kind support.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.(a) Gurak JA, Jr, Yang KS, Liu Z, Engle KM. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:5805–5808. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang KS, Gurak JA, Jr, Liu Z, Engle KM. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:14705–14712. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu Z, Zeng T, Yang KS, Engle KM. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:15122–15125. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liu Z, Wang Y, Wang Z, Zeng T, Liu P, Engle KM. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:11261–11270. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b06520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Liu Z, Ni H-Q, Tian Z, Engle KM. J Am Chem Soc. 2018 doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b00881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaitsev VG, Shabashov D, Daugulis O. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13154–13155. doi: 10.1021/ja054549f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Daugulis O, Roane J, Tran LD. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:1053–1064. doi: 10.1021/ar5004626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) He G, Wang B, Nack WA, Chen G. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:635–645. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For a review, see: Shang X, Liu ZQ. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:3253–3260. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35445d.

- 5.Wang Y, West FG. Synthesis. 2002:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen AL, Ebran JP, Ahlquist M, Norrby PO, Skrydstrup T. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:3349–3353. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu YH, Lu J, Loh TP. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:1372–1373. doi: 10.1021/ja8084548.Feng C, Loh TP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:17710–17712. doi: 10.1021/ja108998d.Zhang Y, Cui Z, Li ZJ, Liu ZQ. Org Lett. 2012;14:1838–1841. doi: 10.1021/ol300442w.. For a selective Ir catalyst, see: Wilklow-Marnell M, Li B, Zhou T, Krogh-Jespersen K, Brennessel WW, Emge TJ, Goldman AS, Jones WD. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:8977–8989. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03433.

- 8.Yu H, Jin W, Sun C, Chen J, Du W, He S, Yu Z. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:5792–5797. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002737.Zhao Q, Tognetti V, Joubert L, Besset T, Pannecoucke X, Bouillon JP, Poisson T. Org Lett. 2017;19:2106–2109. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00704.Yu H, Jin W, Sun C, Chen J, Du W, He S, Yu Z. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:5792–5797. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002737.. For representative examples with other metal catalysts, see: Besset T, Kuhl N, Patureau FW, Glorius F. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:7167–7171. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101340.Shang R, Ilies L, Asako S, Nakamura E. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:14349–14352. doi: 10.1021/ja5070763.Meng K, Zhang J, Li F, Lin Z, Zhang K, Zhong G. Org Lett. 2017;19:2498–2501. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00695.

- 9.Xu YH, Chok YK, Loh TP. Chem Sci. 2011;2:1822–1825. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Li L, Chu Y, Gao L, Song Z. Chem Commun. 2015;51:15546–15549. doi: 10.1039/c5cc06448a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hu XH, Yang XF, Loh TP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:15535–15539. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.da Silva MJ, Gonçalves JA, Alves RB, Howarth OW, Gusevskaya EV. J Organomet Chem. 2004;689:302–308. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Wen ZK, Xu YH, Loh TP. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:13284–13287. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang X, Wang M, Zhang MX, Xu YH, Loh TP. Org Lett. 2013;15:5531–5533. doi: 10.1021/ol402692t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liang QJ, Yang C, Meng FF, Jiang B, Xu YH, Loh TP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:5091–5095. doi: 10.1002/anie.201700559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai H-C, Huang Y-H, Chou C-M. Org Lett. 2018 doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.An example of AQ-directed C(aryl)–H alkenylation via a six-membered palladacycle was reported: Deb A, Bag S, Kancherla R, Maiti D. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:13602–13605. doi: 10.1021/ja5082734.. When 1a was subjected to these reaction conditions, no product formation was observed.

- 15.Bäckvall JE, Byström SE, Nordberg RE. J Org Chem. 1984;49:4619–4631. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Most of the substrates are pure Z alkenes (Z/E>20/1). For detailed stereoisomer ratio of the substrate, please see SI.

- 17.For clarity, throughout this manuscript E/Z notation is used to refer to the alkene stereochemistry of the starting material prior to C(alkenyl)–H activation.

- 18.Selected references: Qin HL, Zheng Q, Bare GAL, Wu P, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:14155–14158. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608807.Zha GF, Zheng Q, Leng J, Wu P, Qin HL, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:4849–4852. doi: 10.1002/anie.201701162.

- 19.Selected references on relevant reactivity: Yamamura K. J Org Chem. 1978;43:724–727.Zhang Q, Lu X. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:7604–7605.Zhao L, Lu X, Xu W. J Org Chem. 2005;70:4059–4063. doi: 10.1021/jo050121n.

- 20.Bäckvall JE, Awasthi AK, Renko ZD. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:4750–4752. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solin N, Szabó KJ. Organometallics. 2001;20:5464–5471. [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Henry PM. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:7316–7322. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zawisza AM, Bouquilon S, Muzart J. Eur J Org Chem. 2007;23:3901–3904. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sen A, Lai TW. Inorg Chem. 1981;20:4036–4038. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu JQ, Gaunt MJ, Spencer JB. J Org Chem. 2002;67:4627–4629. doi: 10.1021/jo015880u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.For structure and reactivity of the White catalyst, see: Chen MS, Prabagaran N, Labenz NA, White MC. J Am Soc Chem. 2005;127:6970–6971. doi: 10.1021/ja0500198.

- 26.Deguchi T, Xin HL, Morimoto H, Ohshima T. ACS Catal. 2017;7:3157–3161. [Google Scholar]

- 27.For related structures, see: Ryabov AD, van Eldik R, Le Borgne G, Pfeffer M. Organometallics. 1993;12:1386–1393.Antonova AB, Starikova ZA, Deykhina NA, Pogrebnyakov DA, Rubaylo AI. J Organomet Chem. 2007;692:1641–1647.Chai DI, Thansandote P, Lautens M. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:8175–8188. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100210.Sasano K, Takaya J, Iwasawa N. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:10954–10957. doi: 10.1021/ja405503y.

- 28.Giri R, Maugel N, Foxman BM, Yu JQ. Organometallics. 2008;27:1667–1670. [Google Scholar]

- 29.These results are consistent with computed activation free energies with other density functionals. See SI for details.

- 30.Herbert MB, Suslick BA, Liu P, Zou L, Dornan PK, Houk KN, Grubbs RH. Organometallics. 2015;34:2858–2869. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Legault CY, Garcia Y, Merlic CA, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12664–12665. doi: 10.1021/ja075785o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.