Abstract

Introduction

Because of their high risk of stroke, anticoagulation therapy is recommended for most patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). The present study evaluated the use of anticoagulants in the community and in a hospital setting for patients with AF and its associations with stroke.

Methods

Patients admitted with stroke to four major hospitals in County of Surrey, England were surveyed in the 2014–2016 Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme. Descriptive statistics was used to summarise subject characteristics and χ² test to assess differences between categorical variables.

Results

A total of 3309 patients, 1656 men (mean age: 73.1 years±SD 13.2) and 1653 women (79.3 years±13.0) were admitted with stroke (83.3% with ischaemic, 15.7% haemorrhagic stroke and 1% unspecified). AF occurred more frequently (χ2=62.4; p<0.001) among patients admitted with recurrent (30.2%) rather than with first stroke (17.1%). There were 666 (20.1%) patients admitted with a history of AF, among whom 304 (45.3%) were anticoagulated, 279 (41.9%) were untreated and 85 (12.8%) deemed unsuitable for anticoagulation. Of the 453 patients with history of AF admitted with a first ischaemic stroke, 138 (37.2%) were on anticoagulation and 41 (49.6%) were not (χ2 = 6.3; p<0.043) and thrombolysis was given more frequently for those without prior anticoagulation treatment (16.1%) or unsuitable for anticoagulation (23.6%) compared with those already on anticoagulation treatment (8.3%; χ2=10.0; p=0.007). Of 2643 patients without a previous history of AF, 171 (6.5%) were identified with AF during hospitalisation. Of patients with AF who presented with ischaemic stroke who were not anticoagulated or deemed unsuitable for anticoagulation prior to admission, 91.8% and 75.0%, respectively, were anticoagulated on discharge.

Conclusions

The study highlights an existing burden for patients with stroke and reflects inadequate treatment of AF which results in an increased stroke burden. There is significant scope to improve the rates of anticoagulation.

Keywords: stroke medicine, cardiology, adult cardiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strengths of the present study include its stable and relatively large homogenous cohort of patients derived from one of the largest NHS regions in England.

The data were meticulously collected with few missing data by healthcare providers for the patients using national Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP) protocol.

Although data are derived only from Surrey, it is likely to be representative nationally as stroke prevalence and characteristics are similar to those presented in the SSNAP report.

Limitations in the present study include the lack of information to explain the reasons for not anticoagulating patients with atrial fibrillation in the community.

Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of death in the world, affecting about 6.7 million cases per annum (11.9% of all deaths).1 Physical disability and cognitive impairment including dementia arising from stroke are common2–4 and have profound effects on patients and their carers. These include a high burden of care,5 stress and strain6 and depression,7 and all impose enormous pressure on social and healthcare systems.8 9 There are a number of risk factors for stroke including older age, hypertension, diabetes, previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA), heart diseases including coronary heart disease, cardiomyopathy and heart failure, while atrial fibrillation (AF) is the greatest risk factor, raising the risk of ischaemic stroke by fivefold.10–12

Both AF and stroke are ageing-related conditions and it is crucial that AF is detected and treated early to prevent stroke. Since the 1980s numerous clinical trials have examined the effectiveness of antithrombotic agents such as warfarin and antiplatelet agents (aspirin and dipyridamole). A meta-analysis showed that warfarin treatment for AF reduced the risk of stroke by 64% while antiplatelet agents reduced it by 22%.13 Analysis of pooled data from five randomised controlled trials11 showed that warfarin treatment consistently reduced the risk of embolic stroke by 60%–84% while the risk of major bleeding was only marginally different from controls or those treated with aspirin (1.3% vs 1.0%). The efficacy of aspirin was variable across the five studies showing risk reduction of 18% with low dose (75 mg/day) and with higher dose (325 mg/day). As such, modern guidelines do not recommend the use of Aspirin or antiplatelet agents as adequate stroke prevention strategy in patients with underlying non-valvular AF.14–16 Based on evidence from previous clinical trials, anticoagulation by warfarin or non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (novel oral anticoagulants) have been favourably recommended for routine treatment of AF over the past three decades.15–18 However, there is evidence of undertreatment of AF in the community19–21 which associates with increased risk of nosocomial pneumonia, prolonged stay in hyperacute stroke units, disability on discharge and inpatient mortality.22

The present study evaluated the use of anticoagulation in patients with AF and its implications on the development of stroke in the County of Surrey, England.

Methods

Study design, participants and setting

We conducted a cross-sectional study using data from the Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP) which is the registry-based study launched in 2012 by the Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, collecting all data submitted by sites via a web-based tool.14 The results reflect the organisation of stroke services and contains national and site level figures to allow benchmarking of performance over time and comparisons between regions. SSNAP targets the participating stroke teams, medical directors, managers and trust executives.14

We used an anonymised extract of a total of 3309 patients admitted to four hyperacute stroke units in the County of Surrey (one of the largest National Health Service regions in England).22 The sites which included Ashford and St Peter’s (n=1038), Frimley Park (n=1010), Royal Surrey County (n=612) and Epsom General (n=649) hospitals, were surveyed between January 2014 and February 2016. Twenty-four patients were admitted multiple times and therefore data from their first admission were used for analysis. This study population was relatively homogenous and stable, comprising 92.1% white Caucasians, 6.8% Asian, Black, mixed race and other ethnic populations and 1.2% not stated.

SSNAP has approval from the Confidentiality Advisory Group of the Health Research Authority to collect patient data under section 251 of the National Health Service Act 2006. No additional ethical approval was sought.

Patient and public involvement

Development of the importance of this research question was discussed with the UK national charity for stroke victims, Different Strokes. The design, recruitment, analyses and conclusions however were conducted by the investigators alone. Results of this study will be disseminated to participants by presentation at our local meetings.

Data recording

All four study centres participated in SSNAP and therefore used an identical protocols and data collection methodology (available on request). Information on sociodemographic (age at arrival, sex and ethnicity) and clinical factors as well as investigations were collected on an admission proforma. History of AF, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and congestive cardiac failure, regular medications including antiplatelets and anticoagulants was recorded from clinical history, notes review and family doctor records. The look-back period was not fixed for all the patients. In addition, details of new-onset AF cases, defined by presence of AF in two consecutive 12-lead recordings by electrocardiography, treatment from the point of admission to discharge including anticoagulation and thrombolysis were documented by stroke team comprising consultants and stroke nurse specialists.

Diagnosis of stroke

Stroke is defined as a clinical syndrome, of presumed vascular origin, typified by rapidly developing signs of focal or global disturbance of cerebral functions lasting more than 24 hours. As for the largest amount of literature in stroke, the diagnosis of stroke was based on clinical experience with the support of neuroimaging when necessary. All stroke specialists involved in our study were fully trained stroke physicians according to the UK National criteria.23 Ischaemic stroke was defined as stroke caused by a blocked artery and haemorrhagic stroke as a bleed on the brain caused by a ruptured artery.14 Patients considered to have a first stroke were those without a previous history of stroke, while those considered with recurrent stroke were patients with a recorded previous history of stroke.

Stroke risk calculations

The risk of stroke in patients with AF was calculated using CHADS2 (congestive heart failure=1, hypertension=1, age ≥75 years=1, stroke/TIA=2) scoring system with a range of 0–6 points. CHADS2 scores were categorise into three groups of 0, 1 and ≥2 points for analysis in the present study.

Statistical analysis

The frequency of patients with AF using anticoagulation before developing an ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke was assessed by cross tabulation and χ2 tests. Most variables had no missing data, except for information on type of stroke (1%), which were handled in analysis using a ‘listwise deletion of missing data’ approach. Age data are mean ±SD and differences between sexes used a Student’s t-test. Analyses were performed using SPSS V.22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The null hypothesis was rejected when p<0.05.

Results

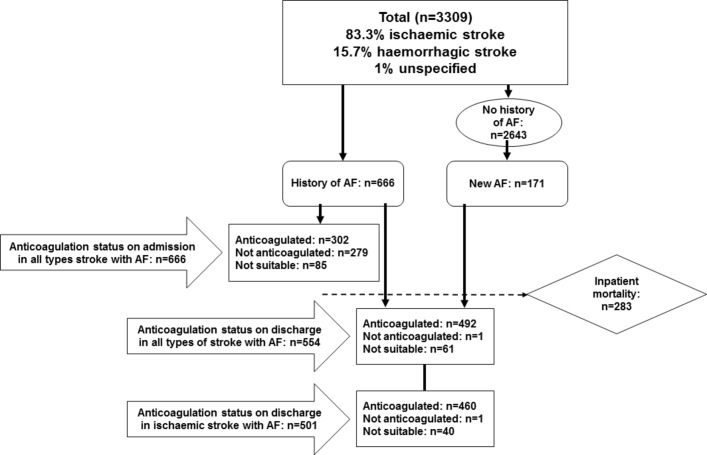

On admission, the proportions of male and female patients were the same. The average age for onset of a first stroke was 6.1 years (95% CI 5.2 to 7.0) earlier in men than in women (p<0.001). There were 76.9% of patients who presented with a first stroke and 23.1% with a recurrent stroke. Of the total number of strokes, 83.3% had ischaemic and 15.7% with haemorrhagic stroke and 1% were unspecified. Thrombolysis was performed in 13.6% of those with an ischaemic stroke. During the period of admission, 171 of the 2643 patients (6.5%) who had no previous history of AF were identified with new onset AF (figure 1). On discharge, 88.8% of patients with AF were anticoagulated (table 1 and figure 2).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the patient cohort investigated in this study. AF, atrial fibrillation.

Table 1.

Distribution of 3309 patients, 1656 men and 1653 women admitted with stroke to hospitals in Surrey between January 2014 and February 2016

| N | Proportion (%) | |

| On admission | ||

| Men (73.1±13.2 years):Women (79.3±13.0 years) | 1656:1653 | 50.0:50.0 |

| First stroke/TIA:Recurrent stroke/TIA | 2543:766 | 76.9:23.1 |

| Ischaemic stroke:Haemorrhagic stroke | 2758:518 | 83.3:15.7 |

| Ischaemic stroke thrombolysis Yes:No:Not suitable |

441:2:2856 | 13.6:0.1:86.3 |

| History of AF and anticoagulation and antiplatelet status | ||

| History of AF:No history of AF | 666:2643 | 20.1:79.9 |

| Anticoagulant treatment status of patients with AF history—Yes:No:Not suitable | 302:279:85 | 45.3:41.9:12.8 |

| Antiplatelet treatment status of patients with AF history—Yes:No:Not suitable | 274:320:72 | 41.1:40.0:10.8 |

| CHADS2 score in patients with history of AF | ||

| 0 | 30 | 4.5 |

| 1 | 148 | 22.2 |

| 2 | 200 | 30.0 |

| 3 | 121 | 18.2 |

| 4 | 125 | 18.8 |

| 5 | 37 | 5.6 |

| 6 | 5 | 0.8 |

| ≥2 | 488 | 73.3 |

| Inpatient | ||

| New AF:No previous history | 171:2643 | 6.5 |

| On discharge | ||

| All patients with stroke | ||

| Patients with AF on discharge | 554 | 16.7 |

| Anticoagulation for AF on discharge | 492 | 88.8 |

| No anticoagulation for AF on discharge | 1 | 0.2 |

| Anticoagulation not suitable for AF | 61 | 11.0 |

| Patients with ischaemic stroke only | ||

| Patients with AF on discharge | 501 | 18.2 |

| No anticoagulation for AF on discharge | 1 | 0.2 |

| Anticoagulation for AF on discharge | 460 | 91.8 |

| Anticoagulation not suitable for AF | 40 | 8.0 |

All data were complete except a diagnosis of ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke in 33 (1.0%) patients.

AF, atrial fibrillation; CHADS2, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, stroke/TIA; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

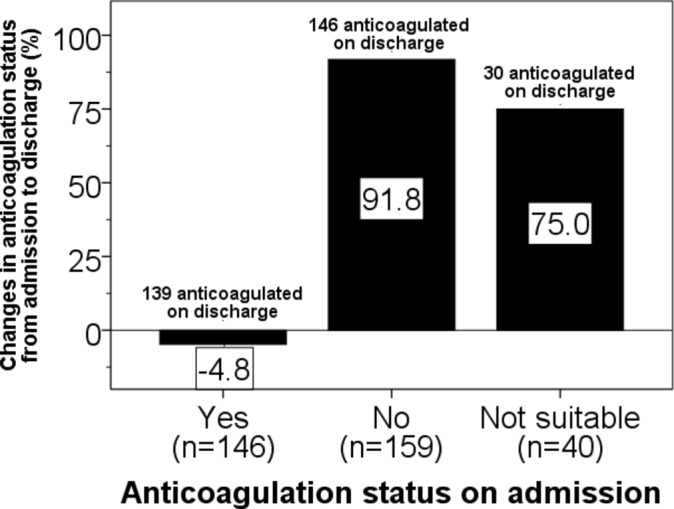

Figure 2.

Patients admitted with ischaemic stroke and AF (n=345) who had their anticoagulation status changed (group differences: χ2=16.2, p<0.001). Numbers of patients with AF according to anticoagulation status on admission are shown in parentheses. AF, atrial fibrillation.

Of those presenting with a first stroke, 1288 were men (72.3±13.5 years) and 1255 women (78.3±13.6 years); of those with a recurrent stroke, there were 368 men (76.3±11.6 years) and 398 women (82.3±10.5 years)— table 2. The proportion of patients with a history of AF was higher (χ2=62.3, p<0.001) among patients who presented with recurrent stroke (30.0%) than those presenting with first stroke (17.1%).

Table 2.

Distribution of 3309 patients with first stroke or recurrent stroke and any history of AF according to sex and previous history of stroke, admitted to hospitals in Surrey between January 2014 and February 2016

| Patients presented with first stroke (n=2543) | Patients presented with recurrent stroke (n=766) | χ² test for group differences | ||||

| N | Proportion (%) | N | Proportion (%) | χ2 | P values | |

| Sex (male:female) | 1288:1255 | 50.6:49.4 | 368:398 | 48.0:52.0 | 1.0 | 0.206 |

| History of AF admitted with ischaemic stroke | 371 | 17.5 | 193 | 30.4 | 50.1 | <0.001 |

| History of AF admitted with haemorrhagic stroke | 61 | 15.6 | 38 | 30.2 | 13.1 | <0.001 |

| History of AF admitted with ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke | 435* | 17.1 | 231* | 30.2 | 62.4 | <0.001 |

*Information on type of stroke was not specified in three cases.

AF, atrial fibrillation.

Of the 666 (20.1%) patients with stroke with a history of AF (table 3), 435 had an ischaemic stroke and 231 a haemorrhagic stroke. For the patients with an ischaemic stroke with AF, 41.6% were being treated in the community with an anticoagulant, 45.7% were not being treated and 12.6% were deemed unsuitable for anticoagulation, that is, those who were known to have AF and for some reason or another, were not considered for anticoagulant treatment in the community. For those admitted with a haemorrhagic stroke, the corresponding proportions were 52.4, 34.6% and 13.0%. The proportion of patients with haemorrhagic stroke treated with anticoagulants was significantly greater. During hospitalisation, 283 with a history of AF or new AF had died.

Table 3.

Anticoagulation status of 666 patients with a known history of AF who developed either a first stroke or a recurrent stroke

| Anticoagulation status on admission for patients with history of AF | Group differences | |||||||

| Yes (n=302) | No (n=279) | Not suitable (n=85) | χ2 | P values | ||||

| n | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| All stroke with AF (n=666) | ||||||||

| Ischaemic (n=435) | 181 | 41.6 | 199 | 45.7 | 55 | 12.6 | 32.6 | <0.001 |

| Haemorrhagic (n=231) | 121 | 52.4 | 80 | 34.6 | 30 | 13.0 | ||

| First stroke with AF (n=432)* | ||||||||

| Ischaemic (n=371) | 138 | 37.2† | 184 | 49.6† | 49 | 13.2 | 20.0 | <0.001 |

| Haemorrhagic (n=61) | 41 | 67.2 | 14 | 23.0 | 6 | 9.8 | ||

| Recurrent stroke with AF (n=228)* | ||||||||

| Ischaemic (n=90) | 92 | 47.7† | 76 | 39.4† | 22 | 13.0 | 12.6 | 0.002 |

| Haemorrhagic (n=38) | 29 | 76.3 | 4 | 10.0 | 5 | 12.5 | ||

| Thrombolysis of ischaemic stroke (n=89) | 28 | 9.3 | 44 | 15.8 | 17 | 20.0 | 9.0 | 0.011 |

*Information on type of stroke was not specified in six cases.

†Differences between groups: χ2=6.3; p=0.043.

AF, atrial fibrillation.

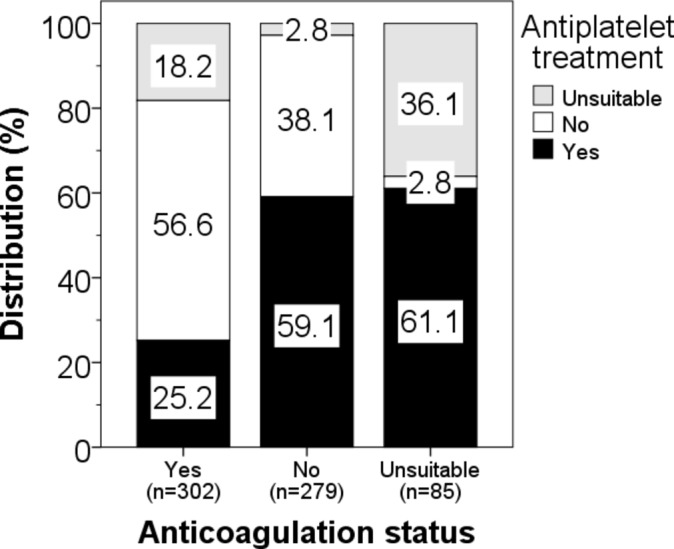

The distributions of patients with AF who were treated with an anticoagulant or with antiplatelet are shown in a stacked bar chart (figure 3). Among 302 patients with AF who were treated with an anticoagulant, 25% were on antiplatelet treatment. The proportions of patients treated with an antiplatelet rose to 59% and 61% among 279 patients with AF who were not treated with an anticoagulant and 85 patients with AF who were deemed not suitable for anticoagulation, respectively.

Figure 3.

Distribution on antiplatelet treatment within each category of anticoagulation status (group differences: χ2=145.3, p<0.001).

The proportion of patients who were anticoagulated prior to admission was significantly (p<0.05) lower for first ischaemic strokes (37.2%) than recurrent ischaemic strokes (47.7%). Because there were similar proportions of patients with first and recurrent ischaemic stroke who were deemed not suitable for anticoagulation (13.2% vs 13.0%), an alternative statement is that for those patients with ischaemic stroke who were not coagulated a higher proportion where in the first compared with recurrent stroke cohorts (49.6% vs 39.4%, χ2=6.3, p=0.043). Thrombolysis at admission was more frequently used for those without prior anticoagulation treatment (15.8%) or unsuitable for anticoagulation (20.0%) compared with those who were anticoagulated in the community (9.3%; χ2=9.0, p=0.011).

On admission, of the 146 patients (43.6%) with AF who were treated with being treated with anticoagulants, seven patients (−4.8%) discontinued on discharge (figure 2). Of the 159 patients who presented with an ischaemic stroke with AF and who were not being treated with anticoagulants on admission, 146 (91.8%) were anticoagulated on discharge. Of the 40 patients with AF who were deemed unsuitable for anticoagulation, 30 (75.0%) were anticoagulated on discharge.

Overall, 315 out of 335 (94.0%) patients with an ischaemic stroke with AF were anticoagulated on discharge, that is, more than double the proportion of patients with AF who were being anticoagulated on admission.

Table 4 shows anticoagulation status in patients with AF prior to admission and on discharge according age, sex and CHADS2 scores. Anticoagulant treatment range between 43% and 50% of patients on admission for all age groups, males and females and CHADS2 scores 1 or ≥2. Anticoagulant treatment was provided in 13% of those with CHADS2 score 0 prior to admission. These figures rose to between 87% and 97% of patients with AF on discharge.

Table 4.

Anticoagulation status on admission and on discharge according to age, sex and CHADS2 categories in patients with AF

| Anticoagulant treatment prior to admission | Group differences | Anticoagulant treatment on discharge | Group differences | |||||||

| Yes n=302 (45.3%) |

No n=279 (41.9%) |

Not suitable n=85 (12.8%) |

χ2 | P values | Yes n=492 (88.8%) |

No n=1 (0.2%) |

Not suitable n=61 (11.0%) |

χ2 | P values | |

| Age | ||||||||||

| <65 years | 18 (43.9%) | 15 (36.6%) | 8 (19.5%) | 4.1 | 0.397 | 35 (92.1%) | 1 (2.6%) | 2 (5.3%) | 17.7 | 0.001 |

| 65–74 years | 41 (45.6%) | 42 (46.7%) | 7 (7.8%) | 77 (93.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (6.1%) | ||||

| ≥75 years | 243 (45.4%) | 222 (41.5%) | 70 (13.1%) | 380 (87.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 54 (12.4%) | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Men | 145 (48.2%) | 113 (37.5%) | 43 (14.3%) | 4.4 | 0.108 | 224 (89.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 26 (10.4%) | 1.0 | 0.604 |

| Women | 157 (43.0%) | 166 (45.5%) | 42 (11.5%) | 268 (88.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 35 (11.5%) | ||||

| CHADS2 | ||||||||||

| 0 | 4 (13.3%) | 20 (66.7%) | 6 (20.0%) | 13.3 | 0.010 | 34 (97.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.9%) | 8.0 | 0.090 |

| 1 | 72 (48.6%) | 59 (39.9%) | 17 (11.5%) | 127 (91.4%) | 1 (0.7%) | 11 (7.9%) | ||||

| ≥2 | 226 (46.3%) | 200 (41.0%) | 62 (12.7%) | 331 (87.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 49 (12.9%) | ||||

AF, atrial fibrillation; CHADS2, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, stroke/TIA; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Discussion

We show that about a fifth of patients admitted with a stroke to Surrey Hospitals between 2014 and 2016 had AF, among whom more than half (54.7%) were untreated with or deemed unsuitable for anticoagulant therapy. AF occurred more often among patients admitted with recurrent stroke (30.2%) than first stroke (17.1%). Thrombolysis was carried out more frequently in those without previous anticoagulation or unsuitable for anticoagulation compared with those who were already anticoagulated. New AF was identified after admission in 6.5% of those who were not known to have history of arrhythmia. More than 90% of patients with AF who were not previously treated with and three-quarters of those who were deemed unsuitable for anticoagulation in the community were anticoagulated on discharge.

The relatively high proportions of patients with AF who were previously untreated (45.7%) with an anticoagulant in the present study are consistent with findings from other studies. Go et al found that only 62% of patients with AF who were eligible for warfarin actually received the drug.12 Similarly, a review by Darkow et al of healthcare claims for about four million members of an organisation revealed that 61% of patients with AF were suitable for anticoagulation but only 39% had started treatment.24 Our study extended to the analysis of changes in anticoagulation from the point of admission to discharge in UK population. The missed opportunity for AF treatment exposes many patients to increased risk of stroke. Analysis of CHADS2 score in relation to anticoagulation status among patients with AF in the community (43%–50%) and on discharge (87%–97%) further affirms our findings of unnecessary undertreatment with an anticoagulant, particularly those at highest risk of stroke (CHADS2 score≥2).

The reasons to explain the lack of anticoagulation of patients with AF are likely to depend heavily on the characteristics of patients and healthcare providers and the interactions between them. Studies have shown poor awareness of AF by patients, with only 49% of those with the condition could name their condition and only about a half knew about the risk of thromboembolism from AF.25 Lack of access or awareness of the availability or healthcare may exist particularly among ethnic minority groups26 or those of lower socioeconomic status.26 27 Other reasons may be a delay for seeing specialists for assessment before commencing anticoagulation. It is therefore important to disseminate information to the public improve awareness of AF and its clinical implications. A study of patients with AF showed that the use of an ‘audiobooklet decision aid’ improved their understanding of the benefits: risks ratio of different treatment options and definitive treatment choices.27

The strengths of the present study include its stable and relatively large homogenous cohort of patients derived from one of the largest NHS regions in England which is likely to be nationally representative as indicated by their similar characteristics to those presented from national SSNAP data.28 The data were meticulously collected with few missing data by healthcare providers for the patients using national SSNAP protocol. It would be of interest to assess the association of atrial flutter and anticoagulation in stroke. Although there is a paucity in published data on anticoagulant treatment of atrial flutter and the risk of stroke, a recent systematic review by Vadmann et al 29 suggested that this condition is associated with increased risk of thromboembolic events. Information of atrial flutter was not included in the SSNAP protocol and therefore it is likely that our study underestimates the association between AF and stroke risk since the proportion of atrial flutter is 16.1% compared with 83.9% of AF in general population.30 Further prospective studies are needed to elucidate the risk and effectiveness of treatment, including anticoagulation, of atrial flutter and stroke outcomes. We did not have information on vascular disease and therefore CHA2DS2VASc score could not be calculated. We believe that CHADS2 score provides adequate information for our purpose in the present study. Limitations in the present study include the lack of information on type of AF, anticoagulants, thromboembolic and bleeding risk factors and reasons for not anticoagulating patients with AF in the community. Patients’ preference may account for a small proportion who were not treated with anticoagulation. In addition, existing contraindications such as risk of falls, history of serious haemorrhage or an adverse reaction to anticoagulants would make some patients unsuitable for anticoagulation. However, after thorough risk assessment, a substantial number of patients in the present study who were previously untreated or deemed unsuitable for anticoagulation treatment in the community were in fact discharged from hospital on anticoagulation therapy, 92% and 75%, respectively. This difference may reflect the reluctance or confidence of community clinicians to prescribe to patients whom they consider to be at high risk of potential side-effects. Lip et al studied 2634 patients and observed that 60.6% (1602) adhered to guideline for antithrombotic therapy, 17.3% (458) were undertreated and 21.7% (574) overtreated. Those who did not adhere to guideline were significantly more common among the elderly (≥75 years) and females. Patients who were detected for the first time or had paroxysmal AF were significantly more likely to be undertreated.31 Lip et al also found that treatment for lone AF tended not to be adhered to guidelines.31 To improve the identification of AF, particularly among those with high risk or low awareness of the condition, routine ECG screening should be implemented. Holter ECG monitoring over 48–72 hours on discharge is routinely performed for patients with thromboembolic stroke but may still miss those with paroxysmal AF. There are devices designed for long period of monitoring such as ‘Reveal Device’, but this technique is invasive and costly. New devices such as hand held devices designed to record cardiac rhythm over a period up to 4 weeks are being evaluated.32

Conclusion

The study highlights an existing burden for patients with stroke in the County of Surrey and reflects inadequate treatment of AF which is associated with increased risk of stroke. There is significant scope to improve the rates of anticoagulation and this is evident through the analysis which demonstrates a high proportion of anticoagulation in previously anticoagulation naïve and also higher risk patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all patients who participated in SSNAP and all those who were involved in the surveys in the study and Dr Adrian Blight (currently at Department of Stroke, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) for his contribution towards data collection from Royal Surrey County Hospital Foundation Trust.

Footnotes

Contributors: TSH and PS reviewed the topic related literature, performed the study concept and analysis design. BA, GG, CB, PK and TP performed the study coordination and data collection. TSH wrote the first draft, analysed and interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. CHF, DF, SS and PS edited the manuscript. All authors checked, interpreted results and approved the final version. TSH and PS are the guarantors for the study.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. WHO. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds)

- 2. Lamassa M, Di Carlo A, Pracucci G, et al. Characteristics, outcome, and care of stroke associated with atrial fibrillation in Europe: data from a multicenter multinational hospital-based registry (The European Community Stroke Project). Stroke 2001;32:392–8. 10.1161/01.STR.32.2.392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crichton SL, Bray BD, McKevitt C, et al. Patient outcomes up to 15 years after stroke: survival, disability, quality of life, cognition and mental health. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:1091–8. 10.1136/jnnp-2016-313361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Corraini P, Henderson VW, Ording AG, et al. Long-Term Risk of Dementia Among Survivors of Ischemic or Hemorrhagic Stroke. Stroke 2017;48:180–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scholte op Reimer WJ, de Haan RJ, Rijnders PT, et al. The burden of caregiving in partners of long-term stroke survivors. Stroke 1998;29:1605–11. 10.1161/01.STR.29.8.1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blake H, Lincoln NB, Clarke DD. Caregiver strain in spouses of stroke patients. Clin Rehabil 2003;17:312–7. 10.1191/0269215503cr613oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berg A, Palomäki H, Lönnqvist J, et al. Depression among caregivers of stroke survivors. Stroke 2005;36:639–43. 10.1161/01.STR.0000155690.04697.c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Youman P, Wilson K, Harraf F, et al. The economic burden of stroke in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoeconomics 2003;21 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):43–50. 10.2165/00019053-200321001-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saka O, McGuire A, Wolfe C. Cost of stroke in the United Kingdom. Age Ageing 2009;38:27–32. 10.1093/ageing/afn281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991;22:983–8. 10.1161/01.STR.22.8.983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Anon. Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 1994;154:1449–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Go AS, Hylek EM, Borowsky LH, et al. Warfarin use among ambulatory patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: the anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. Ann Intern Med 1999;131:927–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:857–67. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Royal College of Physicians. Clinical effectiveness and evaluation unit on behalf of the intercollegiate stroke working party. SSNAP January - March 2016. Public Report. https://www.strokeaudit.org/Documents/National/AcuteOrg/2016/2016-AOANationalReport.aspx

- 15. Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for Management of Patients With Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:e247–e346. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation--developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace 2012;14:1385–413. 10.1093/europace/eus305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Culebras A, Messé SR, Chaturvedi S, et al. Summary of evidence-based guideline update: prevention of stroke in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2014;82:716–24. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. NICE (National-Institute-for-Health-and-Care-Excellence). Atrial fibrillation: the management of atrial fibrillation. 2014. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG180 (Clinical guideline 180) [PubMed]

- 19. Bassand JP, Accetta G, Camm AJ, et al. Two-year outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation: results from GARFIELD-AF. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2882–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perez I, Melbourn A, Kalra L. Use of antithrombotic measures for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Heart 1999;82:570–4. 10.1136/hrt.82.5.570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Waldo AL, Becker RC, Tapson VF, et al. Hospitalized patients with atrial fibrillation and a high risk of stroke are not being provided with adequate anticoagulation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:1729–36. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.06.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Han TS, Fry CH, Fluck D, et al. Evaluation of anticoagulation status for atrial fibrillation on early ischaemic stroke outcomes: a registry-based, prospective cohort study of acute stroke care in Surrey, UK. BMJ Open 2017;7:e019122 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. NICE. Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management [CG68]. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg68/uptake [PubMed]

- 24. Darkow T, Vanderplas AM, Lew KH, et al. Treatment patterns and real-world effectiveness of warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation within a managed care system. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:1583–94. 10.1185/030079905X61956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lane DA, Ponsford J, Shelley A, et al. Patient knowledge and perceptions of atrial fibrillation and anticoagulant therapy: effects of an educational intervention programme. The West Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Project. Int J Cardiol 2006;110:354–8. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meschia JF, Merrill P, Soliman EZ, et al. Racial disparities in awareness and treatment of atrial fibrillation: the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Stroke 2010;41:581–7. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.573907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Man-Son-Hing M, Laupacis A, O’Connor AM, et al. A patient decision aid regarding antithrombotic therapy for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1999;282:737–43. 10.1001/jama.282.8.737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bray BD, Cloud GC, James MA, et al. Weekly variation in health-care quality by day and time of admission: a nationwide, registry-based, prospective cohort study of acute stroke care. Lancet 2016;388:170–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30443-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vadmann H, Nielsen PB, Hjortshøj SP, et al. Atrial flutter and thromboembolic risk: a systematic review. Heart 2015;101:1446–55. 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mareedu RK, Abdalrahman IB, Dharmashankar KC, et al. Atrial flutter versus atrial fibrillation in a general population: differences in comorbidities associated with their respective onset. Clin Med Res 2010;8:1–6. 10.3121/cmr.2009.851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lip GY, Laroche C, Popescu MI, et al. Improved outcomes with European Society of Cardiology guideline-adherent antithrombotic treatment in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the EORP-AF General Pilot Registry. Europace 2015;17:1777–86. 10.1093/europace/euv269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Howlett PJ, Hatch FS, Alexeenko V, et al. Diagnosing paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: are biomarkers the solution to this elusive arrhythmia? Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:1–10. 10.1155/2015/910267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.