Abstract

Introduction

Rapidly expanding digital innovations transform the perception, reception and provision of health services. Simultaneously, health system challenges underline the need for patient-centred, empowering and citizen-engaging care, which facilitates a focus on prevention and health promotion. Through enhanced patient-engagement, patient-provider interactions and reduced information gaps, electronic patient-generated health data (PGHD) may facilitate both patient-centeredness and preventive scare. Despite that, comprehensive knowledge syntheses on their utilisation for prevention and health promotion purposes are lacking. The review described in this protocol aims to fill that gap.

Methods and analysis

Our methodology is guided by Arksey and O’ Malley’s methodological framework for scoping reviews, as well as its advanced version by Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien. Seven electronic databases will be systematically searched using predefined keywords. Key electronic journals will be hand searched, while reference lists of included documents and grey literature sources will be screened thoroughly. Two independent reviewers will complete study selection and data extraction. One of the team’s senior research members will act as a third reviewer and make the final decision on disputed documents. We will include literature with a focus on electronic PGHD and linked to prevention and health promotion. Literature on prevention that is driven by existing discomfort or disability goes beyond the review’s scope and will be excluded. Analysis will be narrative and guided by Shapiro et al’s adapted framework on PGHD flow.

Ethics and dissemination

The scoping review described in this protocol aims to establish a baseline understanding of electronic PGHD generation, collection, communication, sharing, interpretation, utilisation, context and impact for preventive purposes. The chosen methodology is based on the use of publicly available information and does not require ethical approval. Review findings will be disseminated in digital health conferences and symposia. Results will be published and additionally shared with relevant local and national authorities.

Keywords: preventive medicine, telemedicine, information management, information technology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A sensitive and comprehensive search strategy as well as a broader analytical scope will enable a holistic exploration of electronic patient-generated health data (PGHD) use for prevention and health promotion, ultimately overcoming existing literature fragmentation.

The chosen multidimensional focus of the review’s objectives, data extraction and synthesis goes beyond merely describing existing PGHD types, towards exploring the roles of those involved and their contexts, expanding the topic’s conceptual understanding.

As the review’s scope is restricted to health promotion and certain dimensions of prevention, the resulting typology of electronic PGHD as well as the overall findings might not be applicable beyond those domains.

The chosen definition of electronic PGHD, which emphasises the aspect of patient control and distinguishes them from standardised, provider-driven tools, will likely influence the results of this study.

Following accepted scoping review standards, the review will not formally assess the quality of included studies, thus, not allowing for statements on evidence strength.

Background

Emerging and continuously evolving digital innovations, such as wireless mobile devices, wearables, interactive online platforms and electronic data collection tools exert a transformative power on many domains of human action and interaction.1 2 With accelerating public interest in using electronic tools for monitoring, managing and maintaining health and well-being, the healthcare market becomes an increasingly important field of current digital developments.2 The literature often refers to the ‘revolutionary enabling’ potential of digital innovations in facilitating the provision of care, carrying implications for patients, healthcare providers and policy makers.3 4

Rapidly expanding digital ecosystems are defined as highly disruptive and key to improving healthcare while reducing associated costs.5 An illustrative example is the internet of things, broadly defined as the process of connecting and using various daily life objects via the internet.6 7 Those technological advances can facilitate the creation of valuable health information, as well as its effective use for enabling informed decision making and better outcomes.4 Simultaneously, the penetration of interactive, dynamic and connected digital tools in daily living ultimately expands the roles of consumers, patients and care providers.8 Individuals can quantify and track their health by digitally capturing vital parameters and behavioural data, while healthcare providers can potentially use information generated by new technologies to move beyond predominantly curative responsibilities and engage in proactive, predictive and preventive action.8

Parallel and closely related to those new possibilities of capturing one’s own health parameters is the emerging movement of patient-centred or people-centred healthcare.9 10 Traditionally, political decision makers and healthcare providers played predominant roles in shaping the organisation, management and provision of healthcare.9 11 Modern healthcare systems could benefit from higher patient engagement, stronger communication channels, efficient information flows and improved adoption of communication and information technologies.12 13 The Institute of Medicine aims to respond to those needs by emphasising the importance of patient-centred care, defined as the provision of health services that are sensitively tailored around the needs and preferences of those who receive them.14 The global strategy on people-centred care and integrated health services, prepared by the WHO, underlines that a failure to shift towards predominantly consumer-focused practice will inevitably cause fragmentation, inefficiencies and long-term unsustainability.9 Similarly, a conceptual model developed by Scholl et al 15 in 2014 highlights the importance of information exchange, active patient involvement and patient empowerment. Knowledge transfer, flow and accessibility of health data as well as the availability of adequate technology are core facilitators of patient-centred health services.10 Finally, evidence suggests that patient-centredness is associated with higher patient satisfaction and well-being, which in turn can act as mediating factors towards increased patient engagement, health consciousness and improved health behaviour.16

The phenomenon of electronic patient-generated health data (PGHD) can be positioned on the intersection between the digital revolution and the patient-centred care movement. A landmark white paper by the US Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) defines PGHD as ‘health-related data—including health history, symptoms, biometric data, treatment history, lifestyle choices, and other information—created, recorded, gathered, or inferred by or from patients or their designees (ie, care partners or those who assist them) to help address a health concern’.17 18 Electronically captured, shared and used PGHD consists of digital information that is created outside traditional healthcare contexts.17 18 For example, individuals at high risk of chronic disease, such as sedentary and overweight adults, can self-monitor their physical activity at home and easily share their records on interactive, provider-connected online platforms, enabling professional feedback and guidance.19 Similarly, they can self-capture overall health parameters, such as blood pressure, body fat or weight and rapidly transmit their values via online-connected devices. Data sharing can trigger personalised feedback, customised health plans and other persuasive health promotion techniques.20 Those examples amplify the potential of digital health and PGHD as a resource in enabling convenient, person-centred and cost-effective care that is simultaneously proactive, informed and prevention focused.18 21 Despite this study’s focus on prevention and health promotion, it is crucial to acknowledge the importance and applicability of electronic PGHD beyond those domains. In fact, such data can facilitate the treatment and rehabilitation of increasingly prevalent chronic conditions, such as diabetes and heart failure.17 The justification for our limited scope has conceptual and practical reasons, outlined in the Methods section. A more comprehensive and detailed definition of electronic PGHD is also outlined in the methods section of this protocol.

Study rationale

With increasing prevalence of chronic conditions, proactive and preventive action becomes increasingly vital for decision makers, providers as well as patients.22 If implemented effectively, preventive care holds benefits for individuals, healthcare systems, businesses and society as such. It can reduce the risk of disease, discomfort and disability while diminishing avoidable expenditure, promoting a productive workforce and fostering healthy communities.22 Achieving successful prevention ultimately requires a patient-centred approach that facilitates patient engagement and empowerment as well as meaningful patient–provider interactions.22 23

Despite significant PGHD-related challenges, evidence suggests that digitally enabled PGHD utilisation can facilitate both prevention and patient engagement, ultimately reducing unnecessary costs and inefficiencies.12 13 17 24–26 Furthermore, PGHD can add comprehensiveness to the assessment of an individual’s health status by narrowing information gaps, enhancing patient–provider interaction and reducing data errors.25–27 Research also indicates improved health literacy of patients and consumers, as well enhanced knowledge on health conditions and risks.24

Despite those benefits, systematically and comprehensively synthesised knowledge on electronic PGHD utilisation for preventive and health promotion purposes appears to be lacking. Existing research is thematically fragmented, with most primary studies and reviews predominantly focusing on specific types of PGHD at a time. For example, the two scoping reviews by Archer et al and Davis et al address PGHD in relation to personal health records and without a primary focus on prevention and health promotion.28 29 Other studies, such as the ongoing Cochrane review by Ammenwerth et al,30 capture PGHD as an additional functionality of electronic health records, retaining a predominant focus on patient access to provider-generated health information. Further research syntheses outline the impacts of PGHD-linked tools, such as wearables and self-tracking devices, on specific risk factors and conditions. For example, Gierisch et al summarised the effects of wearable sensing technologies on physical activity, Fu et al reviewed the impact of mobile applications, including electronic monitoring and data transmission, on blood glucose levels, while Fletscher et al explored the effects of blood pressure monitoring on health behaviours.31–33 Existing reviews tend to focus on specific forms of PGHD and specific risk factors or conditions, often with reference to disease management. Our proposed review aims to depart from that ‘focused’ approach to holistically address electronic PGHD and their use in preventive and health-promoting activities. We hypothesise that approaching the literature with a broader lens and not limiting our focus to a specific PGHD format will ultimately enable a holistic understanding of where and how successfully PGHD are currently used. Finally, our analysis, being equally encompassing, may provide insights into how electronic PGHD are applied, adding to our knowledge on the contexts of PGHD utilisation and how those might contribute to improvements and success. Achieving that requires a clear framing, for which this protocol provides clear definitions of key terms and concepts.

Study objectives

The overarching objective of the described study is to identify, map and synthesise existing knowledge on the generation, collection, communication, sharing, interpretation, utilisation, context and impact of electronic PGHD for the facilitation and provision of prevention and health promotion. In order to achieve that, as well as guide data extraction and synthesis, we have defined six targeted objectives, classified into three thematically linked components and outlined in box 1.

Box 1. Scoping review objectives.

Overarching objective: identify, map and synthesise existing knowledge on the generation, collection, communication, sharing, interpretation, utilisation, context and impact of electronic patient-generated health data (PGHD) for the facilitation and/or provision of preventive activities and health promotion.

First targeted objective: provide an overview of PGHD types and tools in the context of PGHD for prevention and health promotion:

Identify and map existing types and tools of electronic PGHD. The term ‘types’ encompasses data properties and characteristics, as well as their preventive and health-promoting aims and functions. The term ‘tools’ denotes the used technical infrastructure for PGHD creation and utilisation.

Second targeted objective: explore the roles of patients/consumers, providers and interactivity in the context of PGHD for prevention and health promotion:

Patient/consumer roles: identify and synthesise existing data on patient/consumer roles, activities and literacy, as well as associated barriers and facilitators.

Provider roles: identify and synthesise existing data on provider roles, activities, literacy, the integration of such data in their practice, as well as associated barriers and facilitators.

Interaction: identify and synthesise existing data that link the utilisation of electronic PGHD to patient–provider or patient–technology interaction.

Third targeted objective: explore the implications of PGHD on health outcomes and equity considerations in the context of prevention and health promotion:

Health outcomes: if available, synthesise existing data on the impacts of PGHD on prevention and health promotion-related outcomes.

Equity considerations: identify whether and what proportion of identified literature addresses, explores or mentions actual or potential PGHD implications on health inequities, for example, by addressing the digital divide, sociodemographic characteristics or disadvantaged population groups.

The first targeted objective ultimately aims to enable an improved, comprehensive understanding of PGHD while unifying a currently fragmented literature-base into a structured, practical typology. The second targeted objective aims to facilitate a conceptual understanding of how such data are used to offer preventive activities and health promotion, emphasising on patient activities, provider roles and interactivity. Whenever available, we aim to additionally synthesise PGHD-related challenges, such as of financial, technical, practical and ethical nature. Current gaps in synthesised knowledge related to the utilisation and impact of PGHD for prevention and health promotion purposes underline the importance of those elements. Closely related to that, the last objective aims to synthesise findings on potential impacts and implications of PGHD utilisation on prevention and health promotion-related outcomes as well as considerations regarding health equity. Acknowledging that differences in technological access, use and literacy may replicate social inequities in the digital domain, we consider it essential to capture any indication related to the potential or actual equity implications of electronic PGHD.34 Finally, inherent to our overall aim of mapping and synthesising existing knowledge, we expect to draw final conclusions on current research trends, as well as identify areas with further research needs.

Methods and analysis

Conceptual model and definitions

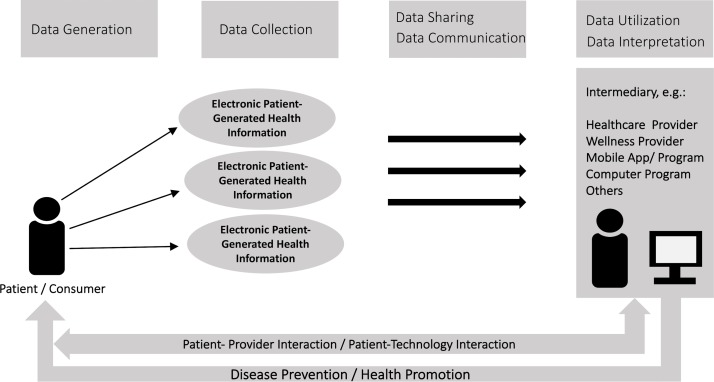

In order to guide and structure the scoping review process, we have adapted and used a conceptual framework that was prepared for the US ONC and reported in a 2012 white paper.17 The original framework visualises the flow and context of PGHD, emphasising on data capture, transfer and review.17 Our adapted version, provided in figure 1, retains the same flow, but additionally emphasises the use of PGHD for fostering or providing disease prevention, health promotion and patient–provider or patient–technology interactions. The framework visualises the generation of different health data types by patients, as well as their collection, sharing, communication and use.

Figure 1.

Adapted framework for patient-generated health data (PGHD) flow and context for prevention and health promotion.17 The framework visualises the flow of PGHD from the patient/consumer (generation and collection stages), passing through intermediaries (communication, sharing and interpretation stages) and back to the patient in form of prevention, health promotion and interaction (utilisation and impact stages).

For the purposes of this study, we propose a more precise definition of electronic PGHD. Accordingly, the term emphasises digital ‘health-related data- including health history, symptoms, biometric data, treatment history, lifestyle choices, and other information—created, recorded, gathered, or inferred by or from patients or their designees (ie, care partners or those who assist them) to help address a health concern’ and are captured outside traditional healthcare contexts. Our definition is limited to predominantly patient or consumer driven PGHD, being distinct from data collected through standardised, provider-driven questionnaires.17 35 Thus, responsibility for capturing, recording and sharing electronic PGHD lies with the patients and consumers.17 We justify that focus on the very nature of prevention and health promotion, which requires an empowered healthcare consumer. To comply with our definition, PGHD should be available in a digital format when used for the intended health-related purposes.

The WHO defines health promotion as any activity that aims to empower people in achieving control over and enhancing their health.36 Prevention is defined as any activity that intentionally aims to impede, reduce or delay the occurrence or progress of physical or mental ill health, injury and premature death.37 Acknowledging that the boundaries between primary, secondary and tertiary prevention, as well as their definitions are neither strictly defined nor clear, especially when it comes to complex chronic conditions, we set our study’s limits around three precise prevention elements and health promotion.38 Thus, to fall within the review’s scope, studies require to be placed in the context of at least one of the following prevention domains: (1) preventing initial occurrence of disease in healthy or high-risk individuals, (2) mitigating risk in healthy or high-risk individuals, (3) monitoring ongoing disease that is free of apparent symptoms in order to avoid progression and (4) promoting health. Clinically managing ongoing disease that is manifested by experienced symptoms, discomfort or disability, therapeutic interventions and rehabilitation fall outside the review’s focus. The reasoning for our narrowed scope is supported by conceptual and practical arguments. Conceptually, we follow Gordon’s classification that restricts the term prevention to primary and secondary levels. However, tertiary prevention follows after disease manifestation, which is in turn driven by different dynamics and often non-distinguishable from therapeutic activities.38 Practically, keeping preventive and therapeutic interventions combined would enormously broaden up our review’s scope and lead to an unmanageable amount of literature.

The term provider is defined as any professional that is responsible for offering health-related services, including health behaviour and lifestyle changes (eg, primary care physicians, primary care nurses, pharmacists, specialist physicians, physiotherapists, psychologists, wellness providers, health and lifestyle coaches). This comprehensive definition aims to maintain a relatively broad scope and reduce the likelihood of missing potential valuable literature. The review will also incorporate studies where healthcare or wellness providers hold secondary roles, such as merely monitoring electronic PGHD, or providing input on the development of preventive digital PGHD-based tools, without direct interaction with patients. Even though the patient–provider interaction and provider involvement might be weak in such scenarios, they are crucial to fully understand the different approaches in using electronic PGHD for preventing disease and promoting health. Finally, table 1 outlines all PGHD dimensions targeted by our review, attaching those to corresponding questions and hypothetical examples.

Table 1.

Targeted PGHD dimensions

| Dimension | Corresponding question and (hypothetical example) |

| PGHD generation | How are PGHD created? (using a digital monitor to self-measure blood pressure) |

| PGHD collection | How are PGHD captured and stored? (storing collected blood pressure values in an online patient portal) |

| PGHD communication and sharing | How are PGHD transferred? (using the patient portal to transfer blood pressure data to the general practitioner via secure email services) |

| PGHD interpretation | How are PGHD reviewed and made sense of? (patient/provider views uploaded blood pressure measurements online over time to understand progress) |

| PGHD purposes | What is the intended purpose for collecting and using electronic PGHD? (self-regulation and personalised feedback) |

| PGHD utilisation | (a) How are PGHD applied for achieving desired results? What is their actual use? (online portal sends provider-initiated feedback emails, based on abnormal values) (b) Is their actual use in line with the intended purposes? |

| PGHD context | What are the settings/environments of PGHD use? (electronic blood pressure measurements taken at home and at the work place) |

| PGHD impact | What are the effects or implications of PGHD? (control and course of blood pressure) |

PGHD, patient-generated health data.

Protocol structure

This protocol is structured and guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework for scoping studies, as well as Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien’s work on advancing that methodology.39 40 The following six sections are categorised according to the elements of that framework. Those include identifying the research question (step 1), identifying relevant studies (step 2), study selection (step 3), charting the data (step 4), collating, summarising and reporting the results (step 5) and stakeholder consultations (step 6).39 40 Furthermore, this protocol follows the reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) checklist for systematic review protocols.41 Falling beyond the scope of a scoping review, the three PRISMA-P elements let aside are the risk of bias assessment, meta-biases and evidence strength (Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE)).41

Step 1: identifying research question

Arksey and O’Malley describe the definition of an appropriate research question as a crucial initial step that defines and refines the chosen research strategy.39 An iterative process of exchange, consultation and literature acquaintance led the development of the review’s guiding questions. An expert has been consulted to provide further input and feedback on our predefined set of core and subquestions. In line with our intention to comprehensively map and synthesise a potentially fast-growing and fragmented volume of literature on electronic PGHD, the review’s primary, overarching research question is defined as: ‘What is our knowledge status, retrieved from existing literature, on the generation, collection, communication, sharing, interpretation, utilization, context and impact of electronic PGHD for the facilitation of patient/consumer-centered preventive activities and health promotion?’. Our question is focused on prevention or health promotion and targets adults. A comparator is not defined, as our search will not be restricted to studies with controls.

Step 2: identifying relevant studies

The identification of relevant literature will consist of several combined approaches, including electronic database searches and complementary activities, such as hand searches of selected online journals, relevant webpages, grey literature sources, reference list screening and expert consultations. Initially, we will systematically search seven electronic databases, including MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase and IEEE Digital Library. Preliminary literature searches, consultation of thematically related reviews, input from the research team and the support of a specialised librarian led to predefined, preliminary search strategy, created on Embase and provided in online supplementary file 1. Our strategy is purposively sensitive, entailing a variety of keywords related to PGHD, restricted to adult populations and research published in the last 15 years. Limiting our research to the last 15 years is based on our preliminary searches that indicate an emergence and accumulation of relevant literature during the last decade. We purposively added another 5 years to ensure that we capture all valuable literature and trends. The final strategy will be refined in a consultation with the experienced librarian who will run all searches. Retrieved documents will be imported into the electronic citation manager Mendeley.

bmjopen-2017-021245supp001.pdf (314.3KB, pdf)

In order to acquire the level of comprehensiveness required for a scoping review, we will also hand search key electronic journals, including the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Associaton (JAMIA), the Journal of Medical Internet Research (JIMR), the International Journal of Digital Healthcare, Digital Health (SAGE) and the Journal of m-Health.39 Grey literature, such as reports, policy briefs, conference abstracts and theses will be retrieved through rigorous searches of the following sources: Grey Literature Report, Open Grey, Web of Science Conference Proceedings and Proquest Dissertations. Ensuring that no relevant publication is missed, we will run several web engine searches using Google, Google Scholar and Yahoo and screening the first 10 result pages. Furthermore, we will screen thematically relevant webpages, such as the ONC, the Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, the Research Triangle Institute International, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Digital Health Canada. Our last research step consists of the manual reference list screening of all eligible studies as well as author consultations, requesting input on potentially missed or unpublished work.

Step 3: study selection

The study selection process will consist of two phases, independently conducted by two members of the research team. The first author of this protocol, having previous experience with literature reviews and an educational background in digital health interventions for disease prevention purposes, will take the first reviewer role. The second reviewer will be recruited based on substantial experience in planning and conducting literature reviews, an educational background in a health-related discipline and a good understanding of the proposed topic, preferably with previous work experience in a PGHD-related topic. Both will be responsible for independently completing the screening, selection and data extraction process, with the first reviewer having the added responsibility of data synthesis and final manuscript preparation. The first study selection phase includes the title and abstract screening of all identified documents. The second phase consists of full-text review of studies that have been classified as potentially eligible during phase one. During both phases, reviewers will assess study inclusion against a set of predefined eligibility criteria. To be eligible, studies have to have a clear focus on electronic PGHD, be linked to disease prevention and health promotion, address adult populations and include some reference to patient and provider involvement. The absence of elements or indicators referring to prevention and health promotion (eg, reduction of blood pressure) or a shallow exploration of patient or provider attitudes towards PGHD and PGHD-based tools, without being clearly defined within a prevention or health promotion context, will lead to exclusion. To ensure that the chosen eligibility criteria are sensitive and clear in capturing relevant documents, they will be pretested by both reviewers on a sample of studies that have been identified during preliminary searches. Maintaining a broad scope, our review will consider any type of primary research study designs as well as grey literature. Relevant systematic reviews will be considered as sources of potentially valuable primary research.

We will assess inter-rater agreement during both phases, using Cohen’s k coefficient.42 The coefficient, calculated after screening the first 50 titles and abstracts, will act as an indicator of whether both reviewers understand and apply the inclusion criteria in an equal, correct and coherent manner. Low agreement (<0.40) will be followed by a consultation of the two reviewers, and if needed, adjustment or rewording of the eligibility criteria. This process will be repeated for the next 50 titles and abstracts and until inter-rater agreement reaches substantial levels (>0.40). After the title and abstract screening is completed, the two reviewers will meet to compare their results. Consulting the inclusion and exclusion criteria, they will try to resolve conflicts and reach consensus on eligibility for full-text review. Studies that are unclear and do not allow for consensus will also enter full-text screening. During full-text review, which will be independently completed by the same two reviewers, inter-rater agreement will be calculated for the first 15 studies. After completion of full-text screening, reviewers will meet again to compare their results. All discordant articles will be re-examined and persisting disputes will be resolved through consultation with a third reviewer, selected among one of the senior members of the research team (MM and MAP) and being responsible for the final decision on disputed papers. Both are members of Cochrane Public Health Europe and have considerable thematic and methodological knowledge. To ensure the highest levels of process transparency and reproducibility, the entire process will be captured and visualised in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart, including the most common exclusion reasons, as well as the final number of included documents.43

Box 2 provides the selected exclusion criteria, carefully chosen to guide the identification of eligible studies while counterbalancing the relatively high sensitivity that is inherent to the review’s broad research question. Documents that fulfil one or more of the statements below will be excluded.

Box 2. Exclusion criteria.

Does not address the generation, collection, communication, sharing, interpretation, utilisation, context or impact of electronic PGHD (as outlined in table 1).

Lacks a focus on prevention and health promotion (eg, exclusively addresses rehabilitation or therapeutic interventions).

Addresses patient-generated information that is not personal health related.

Does not describe, explore and analyse some form of patient and provider involvement.

Does not address or include adults.

Written in a language other than English or German.

Step 4: charting the data

Data extraction will be conducted independently by two reviewers, guided by a predefined, however flexible, data extraction form. The preliminary form is developed by the research team and shown in table 2. It aims to ensure that all required information is captured practically, efficiently and accurately, minimising the risk of missing information. Arksey and O’Malley’s methodological framework suggests charting the data according to central research themes.39 Thus, the chosen data extraction elements have been developed in line with the review’s objectives and corresponding research questions. Next to general information, we aim to retrieve data on PGHD types, patient and provider responsibilities, PGHD impacts on disease prevention and health promotion and equity.

Table 2.

Preliminary data charting elements

| Element and subelement | Associated question |

| Publication details | |

| Author and affiliation | Who wrote the study/document? |

| Type | Is the document an empirical study or grey literature? |

| Year | What year was the study/document published? |

| Country/region | Which country is the study/document focusing on? |

| Funding | Are the funding sources provided? |

| Conflict of interest declaration | Is a conflict of interest statement included? |

| General details | |

| Methodological design | What is the study/document design? |

| Aims | What are the study/document aims? |

| Population | Which is the target population of the study/document? |

| Addressed condition(s), risk factors(s), symptom(s), behaviour(s) or outcome measure(s) | What is the health-related focus of the study/document? |

| Setting | What is the described setting? |

| Perspective (promotion/prevention) | Is the focus on prevention or health promotion? |

| Content | |

Patient roles and activities

|

What are the patient roles and required activities in generating, transferring and using electronic PGHD for prevention/health promotion purposes? |

PGHD types

|

What types of PGHD are addressed? What PGHD-based tools are used? What are the intended PGHD purposes? |

Provider roles and activities

|

What are the provider roles and required activities in integrating and using electronic PGHD for prevention/health promotion purposes? Is the actual PGHD use in line with the indented purposes? |

Interactivity

|

How do electronic PGHD affect or relate to patient–provider, as well as patient–technology interaction? |

| Impact on prevention and health promotion-related outcomes | What is the impact of electronic PGHD use on any outcomes related to prevention and health promotion? |

| Equity considerations | Does the study/document address, explore or refer to actual or potential equity-related implications of PGHD (eg, better results for disadvantaged social groups)? |

| Other important results | Further important results? |

PGHD, patient-generated health data.

The final form will be refined and validated through consultations with the entire research team, as well as expert feedback. As suggested by Levac et al and Daudt et al, the form will be initially and independently tested by two reviewers on a random sample of five studies.40 44 This phase is described as as key to improving the quality and applicability of the data extraction chart.44 It will be followed by consultation to ensure accuracy, consistency and that the captured information contributes to the study’s research questions. Consultation might finally lead to form modifications that have to be reviewed and agreed on by the entire research team.

After completion of the full data extraction process, both reviewers’ final data sets will be compared. Each article will have a unique identification number to enhance process efficiency and practicality. Inconsistencies and disagreements will be discussed, reconsulting the respective documents and if necessary, requesting support by a senior investigator of the team (MM and MAP).

Step 5: collating, summarising and reporting the results

As described by Arksey and O’Malley, a weighted data synthesis and aggregation of findings is not inherently essential to a scoping review, considering the missing assessment of evidence quality and robustness.39 The chosen analytical approach will therefore be of narrative nature, guided by the adapted PGHD flow framework (figure 1) and the review’s objectives.17 Despite its benefits, a quality assessment will not be performed as it does not align with our aim of scoping a potentially large and heterogeneous literature volume.

Initial synthesis will be of basic quantitative nature, summarising the extent, scope and nature of existing literature. Publication types, years, geographic distribution, target populations, target conditions, risks and behaviours, as well as existing methodologies will be synthesised descriptively, using ranges and counts, presented in tables. That step will provide an overview of existing evidence and research activity trends, as well as highlight potential research gaps.39

Further synthesis will remain narrative but also consider quantitative primary data. Tables and figures will summarise key findings, structured around the review’s objectives. The research team and experts will enrich data synthesis through regular input, ensuring validity and transparency. With exception of the risk of bias and evidence strength (GRADE) assessment, the reporting of our results will be guided by the PRISMA reporting guidelines.45 The entire process, including screening (step 3), data extraction (step 4) and synthesis will be conducted with the Covidence Software and Excel. We are not planning any additional analyses.

Step 6: consultation

Levac et al, pointed out that consultation, the sixth transversal optional stage of the scoping studies framework, may enable stakeholder engagement and provide valuable input, beyond the information provided in the literature.40 As already described throughout the protocol, expert consultation is central at all stages of this study. An external expert in the area of PGHD has been consulted twice during the development of this protocol, providing conceptual and content-related feedback and advice. During the review process, we will additionally establish regular consultation with one provider–partner and at least one patient–partner. Both stakeholders will be asked to provide feedback during data extraction, appraisal of preliminary results, data synthesis and interpretation. Finally, we aim to engage digital health experts within the team’s own institution for additional advice. All involved experts and stakeholders will be acknowledged in the final publication.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the design of this protocol. Nonetheless, as outlined in the previous paragraph, at least one patient advisor will be consulted during the implementation stages of our review, asked to provide feedback on the clarity, applicability and value of the review’s findings and interpretations. Any involved patient–partner will receive our preliminary and final results electronically and during consultations.

Ethics and dissemination

The described review constitutes the first step of a larger research project on digital solutions for disease prevention and health promotion. Its results ultimately fulfil the function of establishing a comprehensive conceptual knowledge of electronic PGHD and will be used to inform prospective research steps. As we did not expect or receive any search strategy modifications, searches have been run during January 2018. All other review steps commenced from mid-February 2018 onward, incorporating all reviewer comments. Findings will be disseminated at relevant conferences and symposia. Results will be published and additionally shared with our provider and patient–partners and their networks, as well as local and national organisations operating in the field of digital health. As our methodology is based on the review of publicly available information, ethical approval is not required. Any amendments to this protocol will be documented precisely and listed in the final review publication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Deborah Cohen for her valuable feedback during the development process of this protocol, Mrs Shwu Yee Lun for proofreading the manuscript and both reviewers for their constructive comments.

Footnotes

Contributors: VN: contributed to the conceptualisation of the study and wrote and edited the manuscript. MM and MAP: contributed to the conceptualisation of the study, supervised the entire process and edited the manuscript. FE: provided regular input and edited the manuscript. All authors provided final approval of the final protocol version.

Funding: The first author’s salary is funded by the Béatrice Ederer-Weber Fellowship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Lupton D. Critical perspectives on digital health technologies. Sociol Compass 2014;8:1344–59. 10.1111/soc4.12226 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Castle-Clarke S, Imison C. The digital patient: transforming primary care. London: Nuffield Trust, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kamel Boulos MN, Wheeler S. The emerging Web 2.0 social software: an enabling suite of sociable technologies in health and health care education. Health Info Libr J 2007;24:2–3. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2007.00701.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Were MC, Kamano JH, Vedanthan R. Leveraging digital health for global chronic diseases. Glob Heart 2016;11:459–62. 10.1016/j.gheart.2016.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Intelligence Council. Disruptive technologies global trends 2025. Six technologies with potential impacts on US interests out to 2025. SRI Consulting Business Intelligence 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Swan M. Sensor mania! the internet of things, wearable computing, objective metrics, and the quantified self 2.0. J Sen Act Net 2012;1:217–53. 10.3390/jsan1030217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Niewolny D. How the internet of things is revolutionizing healthcare. NXP 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swan M, Health SM. Health 2050: the realization of personalized medicine through crowdsourcing, the quantified self, and the participatory biocitizen. J Pers Med 2012;2:93–118. 10.3390/jpm2030093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. Geneva: WHO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shaller D. Patient-centered care: what does it take? New York: Commonwealth Fund, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jolley RJ, Lorenzetti DL, Manalili K, et al. Protocol for a scoping review study to identify and classify patient-centred quality indicators. BMJ Open 2017;7:32–5. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sands DZ, Wald JS. Transforming health care delivery through consumer engagement, health data transparency, and patient-generated health information. Yearb Med Inform 2014;9:170–6. 10.15265/IY-2014-0017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blumenthal D. Wiring the health system–origins and provisions of a new federal program. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2323–9. 10.1056/NEJMsr1110507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, et al. An integrative model of patient-centeredness – a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e107828 10.1371/journal.pone.0107828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 2013;70:351–79. 10.1177/1077558712465774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shapiro M, Johnston D, Wald J, et al. Patient-generated health data white paper. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Patient-Generated health data, fact sheet. Washington, DC: HealthIT, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wijsman CA, Westendorp RG, Verhagen EA, et al. Effects of a web-based intervention on physical activity and metabolism in older adults: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e233 10.2196/jmir.2843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Youm S, Liu S. Development healthcare PC and multimedia software for improvement of health status and exercise habits. Multimed Tools Appl 2017;76:17751–63. 10.1007/s11042-015-2998-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. HealthIT. https://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/building-data-infrastructure-support-patient-centered-outcomes (accessed Nov 5 2017).

- 22. National Prevention Council. National prevention strategy, Americas plan for better health and wellness. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thompson TL, Parrott R, Nussbaum JF. The Routledge handbook of health communication. New York, NY: Routledge, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lv N, Xiao L, Simmons ML, et al. Personalized hypertension management using patient-generated health data integrated with Electronic Health Records (EMPOWER-H): six-month pre-post study. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e311 10.2196/jmir.7831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. HealthPort. Patient-generated health data and its impact on health information management, white paper. Alpharetta, GA: Ciox Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kumar RB, Goren ND, Stark DE, et al. Automated integration of continuous glucose monitor data in the electronic health record using consumer technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2016;23:532–7. 10.1093/jamia/ocv206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Accenture Federal Services. Conceptualizing a data infrastructure for the capture, use, and sharing of patient-generated health data in care delivery and research through 2024. Accenture 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Archer N, Fevrier-Thomas U, Lokker C, et al. Personal health records: a scoping review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:515–22. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davis S, Roudsari A, Raworth R, et al. Shared decision-making using personal health record technology: a scoping review at the crossroads. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2017;24:857–66. 10.1093/jamia/ocw172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ammenwerth E, Lannig S, Hörbst A, et al. Adult patient access to electronic health records. The Cochrane Library 2017;2017:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gierisch JM, Goode AP, Batch BC, et al. The Impact of Wearable Motion Sensing Technologies on Physical Activity: A systematic Review. Evidence-based Synthesis Program 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fu H, McMahon SK, Gross CR, et al. Usability and clinical efficacy of diabetes mobile applications for adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017;131:70–81. 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fletcher BR, Hartmann-Boyce J, Hinton L, et al. The effect of self-monitoring of blood pressure on medication adherence and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens 2015;28:1209–21. 10.1093/ajh/hpv008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McAuley A. Digital health interventions: widening access or widening inequalities? Public Health 2014;128:1118–20. 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cohen DJ, Keller SR, Hayes GR, et al. Integrating patient-generated health data into clinical care settings or clinical decision-making: lessons learned from project healthdesign. JMIR Hum Factors 2016;3:e26–10. 10.2196/humanfactors.5919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. World Health Organization. Health promotion. http://www.who.int/topics/health_promotion/en/ (accessed Nov 2 2017).

- 37. Tengland PA. Health promotion or disease prevention: a real difference for public health practice? Health Care Anal 2010;18:203–21. 10.1007/s10728-009-0124-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gordon RS. An operational classification of disease prevention. Public Health Rep 1983;98:107–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69–78. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cohen J. A Coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 1960;20:37–46. 10.1177/001316446002000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Daudt HM, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:48 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000100 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021245supp001.pdf (314.3KB, pdf)