Abstract

Objectives

Dysfunction after transient ischaemic attack (TIA) and minor stroke is often underestimated by clinical measures. Patient-reported outcome measures used in value-based healthcare may help in detecting these problems. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 10-Question Short Form (PROMIS-10 Global Health) is a concise patient-centred outcome measuring tool proposed for assessing health status in patients who had stroke. This study aims to address the validity of the Dutch PROMIS-10 in patients who had stroke in the Netherlands and also aims to compare telephone versus on-paper assessment.

Design

Observational cohort study.

Setting

Single-centre hospital in the Netherlands.

Participants

75 patients who were diagnosed with TIA or minor stroke and discharged without rehabilitation treatment 1 year ago (between December 2014 and January 2016) completed the study.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

PROMIS-10 physical (PH) and mental health (MH) scores assessed 1 year poststroke on paper (n=37) and by telephone (n=38) was compared with RAND-36 physical and mental component scores assessed on paper.

Results

PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 correlated significantly in PH, r=0.81 (95% CI 0.69 to 0.88), and MH, r=0.76 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.85). Paper-and-pencil assessed correlations were r=0.87 and 0.79 for PH and MH, respectively. Telephone assessed correlations were r=0.76 and 0.73 for PH and MH, respectively. Internal consistency analysis indicated high reliabilities for both health components of the PROMIS-10, all Cronbach’s α>0.70.

Conclusions

The Dutch PROMIS-10 was found to strongly correlate with the RAND-36. Paper-and-pencil assessment was found to have a higher correlation than telephone assessment. This study provides support for the use of the Dutch PROMIS-10 in assessing health status in patients after TIA and minor stroke.

Keywords: stroke, transient ischemic attack, quality of life, patient-reported outcomes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study that addresses the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 10-Question Short Form (PROMIS-10) as a measuring tool for health status in patients who had transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke in the Netherlands.

Subjects were very similarly distributed in terms of clinical and socioeconomic factors between different comparator groups.

Generalisability of the study results is reduced due to a relatively small sample size.

There was a time window between assessment of paper-based RAND-36 and telephone-based PROMIS-10.

PROMIS-10 was assessed at one time point only; this study provides no insight on test–retest reliability of the PROMIS-10.

Introduction

Following a stroke, many patients experience persistent deficits and reduced functional independence,1 while full recovery is assumed in patients who had transient ischaemic attack (TIA) and minor stroke who are discharged home without further rehabilitation treatment.2 However, previous studies in patients who had TIA and minor stroke found high prevalence of dysfunction across all domains of health, of which cognitive and emotional problems were most notable.3–6 These symptoms may be overlooked with conventional clinical measures such as the neurological examination or the Barthel Index, but can be a major contributor to an impaired performance of activities of daily living and a diminished quality of life (QoL).2 7–9 This emphasises the importance of patient-reported outcomes (PROs), which measure health status reported directly from the patient.10 Measuring PROs is also an essential principal in the emerging value-based healthcare.11 As such, health measurement is shifting from process measurement towards outcome measurement to improve quality while reducing costs.12 This initiated the proposal of a Stroke Standard Set for measuring health in stroke by the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM).13 The expert group recommends the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 10-Question Short Form (PROMIS-10 Global Health) for assessing health status after stroke.14 The PROMIS-10 has been translated into Dutch by the Dutch-Flemish PROMIS group (http://www.dutchflemishpromis.nl), but has not yet been validated or compared with existing validated instruments in patients who had stroke.15

Aims

This study aims to investigate the construct validity and reliability of the Dutch PROMIS-10 in patients who had TIA and minor stroke in the Netherlands. We also aim to evaluate different assessment methods of the PROMIS-10: on paper (filled in by the patient) assessment versus assessmentthrough the telephone. Since telephone assessment might be more feasible than on paper assessment in a population consisting of mainly elderly patients.

Methods

Study design

This single-centre observational cohort study was part of a concurrent QoL study at OLVG Oost Hospital. Between January 2016 and January 2017, medical records of patients diagnosed with a TIA or minor stroke 1 year ago were screened for eligibility, as Mierlo et al reported improvement of QoL occurring the most in the first 6 months and up to 1 year after stroke.16 Eligible patients were approached by telephone for study participation. Following verbal consent to study participation, study materials were sent by mail: study information, consent form, PROMIS-10, RAND-36 (a health-related QoL measure) and a short form for obtaining sociodemographic data. PROMIS-10 was assessed on paper from 1 January to 31 July 2016 and by telephone from 1 August 2016 to 31 January 2017. On paper, assessments of the PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 were completed by the patients at home on their own or with help of a proxy. Telephone assessments of the PROMIS-10 were carried out by reading out the exact questions and marking the given answers. Clinical data were extracted from medical records. Full ethical approval was given. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Clinical data (age, gender, diagnosis, stroke localization and incidence) of non-participating and excluded eligible patients were recorded in a non-identifiable manner without requiring consent.

Subjects

Eligibility included a clinical diagnosis of TIA or minor stroke followed by discharge without inpatient rehabilitation treatment. MRI is not part of the standard diagnostic work-up of stroke but was performed whenever other causes than ischaemia could not be ruled out. For this study, TIA and minor stroke were defined as acute neurological deficits with symptoms of stroke on admission that fully resolves within 24 hours and 3 days, respectively.

As standard practice, patients discharged home following a TIA or stroke, are re-evaluated shortly after discharge by a specialised stroke nurse. If during the re-evaluation residual or new symptoms are present or suspected, patients are referred to the Beroerte Adviescentrum (BAC, ’Stroke Advice Centre'), a central body that coordinates and effectuates outpatient care for patients who had stroke. As the BAC measures baseline health status, which is an inclusion criterion for the concurrent QoL study, patients who were not referred to the BAC or did not complete baseline measurements were deemed ineligible.

Exclusion criteria were: age below 18 years, persistent neurological symptoms 3 days poststroke, insufficient proficiency in Dutch, dementia or any behavioural disorder that may compromise study participation.

Measures

The PROMIS-10 is a 10-item measure for self-reported QoL, physical health (PH) and mental health (MH). It has been shown to be reliable, precise and comparable to legacy instruments.17 PH and MH T-scores can be calculated through an online scoring service provided by Assessment Centre (www.assessmentcenter.net/ac_scoringservice). The T-score distributions are standardised with a mean (SD) of 50 (10) for the US general population, where higher scores indicate better outcome. In this study, a Dutch version of the PROMIS-10 was used.15 As standardised scores for the Netherlands are unavailable, T-scores were calculated using the US population standard scores.

The RAND-36 (identical to the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey) is a widely used QoL measure, comprising 36 items covering a wide range of health domains.18 Two component scores can be derived: physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) component score. PCS and MCS are standardised with a mean (SD) of 50 (10), with higher scores reflecting better outcome. The RAND-36 has been translated and validated into multiple languages, including Dutch.19 In this study, the Dutch RAND-36 V.2 was used. However, PCS and MCS were calculated using US-standardised weights for a more equal comparison to the PROMIS-10, which was calculated similarly.

Sociodemographic data collected were: marital status, level of education (assessed on the Dutch seven-point scale ‘schaal van Verhage’, and afterwards stratified into three groups: low (primary school), average (secondary school low or medium level) and high (highest level secondary school, and/or college degree, and/or university degree),20 living arrangement and work status.

Data analysis

Numerical variables were summarised by the mean±SD, and frequencies and percentages were used for binary and categorical variables. Differences in patient characteristics were assessed using the independent samples t-test and χ² test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. For assessing construct validity, correlation between PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 was assessed by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r), with a bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrapping method providing 95% CIs. Agreement between PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 was assessed by constructing Bland-Altman plots with horizontal lines representing the mean difference and 95% limits of agreement (LOA) (mean difference±1.96 SD).21 An independent samples t-test was performed for assessing differences between assessment methods of the PROMIS-10. For the internal consistency of the PROMIS-10, reliability analysis was used to calculate Cronbach’s α for both physical (four items) and mental (four items) subscales. A cut-off point of ≥0.70 was chosen for indication of good reliability (α) and correlation (r).22 A p value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS V.22.

Patient and public involvement

The development of the research question was based on earlier research on patients’ experience of our care after a TIA or minor stroke. Many patients had hidden signs and symptoms that were not recognised by doctors at first sight. We are now developing ‘Value-based healthcare’ with the help of patient-related outcome measures like the one that is investigated in this study, to be able to detect these hidden signs and symptoms. In the informed consent form, we stated that after the end of the study, we will send a letter to the participants to inform them about the results of the study.

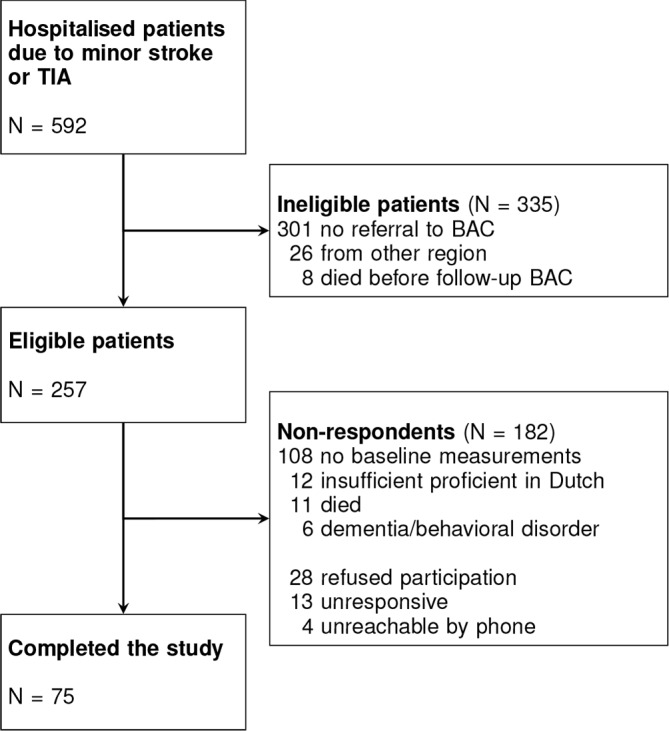

Results

A total of 592 patients were identified who were diagnosed with a TIA or minor stroke 1 year prior to the assessment (from December 2014 to January 2016). Following re-evaluation by their physician, 301 patients were not referred to BAC for follow-up care, 26 patients originated from a different region or country, and eight died before BAC follow-up. Of the remaining 257 eligible patients, 182 were non-respondents (108 had no baseline measurements, 12 were insufficient proficient in Dutch, 11 died before follow-up at 1 year poststroke, six had dementia or a behavioural disorder, 28 refused participation, 13 were not responsive after initial consent and four were not reachable by phone) and 75 patients were included for the study (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population. BAC, Beroerte Adviescentrum; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Of the 75 included patients, mean age was 68.9±11.2 years, 51 (68.0%) were men, 60 (80.0%) had their first-ever ischaemic event, 49 (65.3%) had the diagnosis of minor stroke and 26 (34.7%) TIA. The ischaemic event was located in the left hemisphere in 30 (40.0%) patients, 23 (30.7%) in the right hemisphere and 22 (29.3%) were vertebrobasilar. There were no statistically significant differences between the study population and the non-respondents. Mean (SD) scores for the PROMIS-10 were 45.8 (9.9) for PH and 49.6 (9.1) for MH. Scores for the RAND-36 were 43.7 (11.4) for PCS and 49.9 (10.7) for MCS.

In 37 patients, the PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 were assessed on paper; two had missing values in the physical total score, and one in both physical and mental total score of the PROMIS-10, another patient had missing values in both component scores of the RAND-36. These 37 patients formed the ‘paper-and-pencil group’. Thirty-eight patients completed the PROMIS-10 by telephone (and the RAND-36 on paper); these patients formed the ‘telephone group’. Patient characteristics of both groups are summarised in table 1. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of the study population (n=75, divided in ‘paper-and-pencil’ and ‘telephone’ group) and non-respondents (n=182)

| Characteristic | Study population (n=75) | Non-respondents (n=182) | P value | ||

| ‘Paper-and-pencil’ (n=37) | ‘Telephone’ (n=38) | P value | |||

| Days between onset and follow-up, mean (SD) | 374.8 (59.7) | 375.7 (30.7) | n/a | ||

| Age, year, mean (SD) | 67.4 (9.9) | 70.4 (12.2) | 0.258* | 68.5 (12.2) | 0.810* |

| Gender | 0.160† | 0.053† | |||

| Female | 9 (24.3) | 15 (39.5) | 82 (45.1) | ||

| Male | 28 (75.7) | 23 (60.5) | 100 (54.9) | ||

| Diagnosis | 0.170† | 0.086† | |||

| TIA | 10 (27.0) | 16 (42.1) | 44 (24.2) | ||

| Minor stroke | 27 (73.0) | 22 (57.9) | 138 (75.8) | ||

| Localisation | 0.921† | 0.683‡ | |||

| Right hemisphere | 12 (32.4) | 11 (28.9) | 51 (28.0) | ||

| Left hemisphere | 14 (37.8) | 16 (42.1) | 77 (42.3) | ||

| Vertebrobasilar | 11 (29.7) | 11 (28.9) | 47 (25.8) | ||

| Ocular | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.6) | ||

| Other/unknown | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.2) | ||

| Stroke incidence | 0.729† | 0.469† | |||

| First ever | 29 (78.4) | 31 (81.6) | 138 (75.8) | ||

| Relapse | 8 (21.6) | 7 (18.4) | 44 (24.2) | ||

| Marital status | 0.999‡ | ||||

| Married | 22 (59.5) | 22 (57.9) | n/a | ||

| Unmarried | 13 (35.1) | 14 (36.8) | n/a | ||

| Widowed | 2 (5.4) | 2 (5.3) | n/a | ||

| Education | 0.532‡ | ||||

| Low | 5 (13.9) | 3 (7.9) | n/a | ||

| Average | 16 (44.4) | 21 (55.3) | n/a | ||

| High | 15 (41.7) | 14 (36.8) | n/a | ||

| Living arrangement | 0.925† | ||||

| Alone | 15 (40.5) | 15 (39.5) | n/a | ||

| With spouse/relative(s) | 22 (59.5) | 23 (60.5) | n/a | ||

| Current work status | 0.969† | ||||

| Back to work | 8 (21.6) | 8 (21.1) | n/a | ||

| Not (fully) back to work | 6 (16.2) | 7 (18.4) | n/a | ||

| Retired | 23 (62.2) | 23 (60.5) | n/a | ||

All data are expressed as n (%), except where specified.

*t-test.

†χ2 test.

‡Fisher’s exact test.

TIA, transient ischaemic attack; n/a, not available.

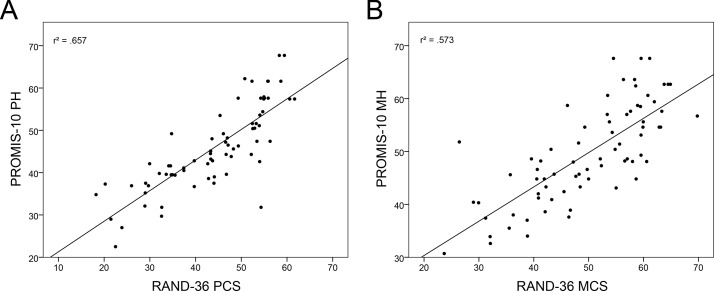

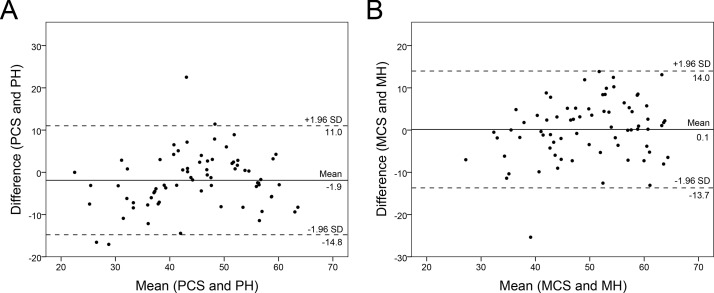

Construct validity

PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 physical and mental scores correlated significantly, r=0.81, 95% BCa CI 0.69 to 0.88, p<0.001, and r=0.76, 95% BCa CI 0.64 to 0.85, p<0.001, respectively (see figure 2). Figure 3 shows the Bland-Altman plots for PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 PH and MH. The mean difference between the measures were −1.9 and 0.1 for PH and MH, respectively. For both PH and MH, the paired differences and averages were fairly evenly scattered within the upper and lower LOA.

Figure 2.

Scatterplots of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 10-Question Short Form (PROMIS-10) and RAND-36 physical (A) and mental health scores (B).

Figure 3.

Bland-Altman plots of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 10-Question Short Form (PROMIS-10) and RAND-36 physical (PH) (A) and mental health (MH) scores (B). The mean of both measures (x-axis) was plotted against their difference (y-axis). The continuous line represents the mean difference and the dashed lines represent the 95% limits of agreement. MCS, mental component score; PCS, physical component score.

When scores for the PROMIS-10 PH and MH were divided between ’paper-and-pencil' and ’telephone' groups, correlation between the PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 PH and MH increased in the ’paper-and-pencil' group and decreased in the ’telephone' group. The results are summarised in table 2. Mean PH score was lower in the ’paper-and-pencil' group than in the ’telephone' group. This difference was not statistically significant. The mean MH score was also lower in the ’paper-and-pencil’ group than in the ’telephone' group. This difference, however, was statistically significant. Mean scores of the RAND-36 PCS and MCS were not statistically significantly different among the two groups based on assessment method of PROMIS-10. The results are summarised in table 3.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations between PROMIS-10 and RAND-36

| RAND-36 | n | ||

| PCS | MCS | ||

| PROMIS-10 | |||

| PH | 0.82* (0.70 to 0.90) | – | 71 |

| MH | – | 0.70* (0.57 to 0. 82) | 73 |

| PROMIS-10 (paper-and-pencil) | |||

| PH | 0.88* (0.78 to 0.93) | – | 33 |

| MH | – | 0.70* (0.54 to 0.84) | 35 |

| PROMIS-10 (telephone) | |||

| PH | 0.77* (0.54 to 91) | – | 38 |

| MH | – | 0.70* (0.50 to 0.86) | 38 |

*P<0.01. BCa bootstrap 95% CIs reported in brackets.

MCS, mental component score; MH, mental health; PCS, physical component score; PH, physical health; PROMIS-10, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 10-Question Short Form.

Table 3.

Independent samples t-tests comparing PROMIS-10 and RAND-36, between ‘paper-and-pencil’ and ‘telephone’ group

| ‘Paper-and-pencil' | ‘Telephone’ | 95% CI for mean difference | t-value (df) | P value | |||

| Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | ||||

| PROMIS-10 PH | 44.1 (10.1) | 34 | 47.2 (9.5) | 38 | −7.67 to 1.57 | −1.32 (70) | 0.192 |

| PROMIS-10 MH | 45.6 (8.5) | 36 | 53.4 (8.0) | 38 | −11.57 to –3.90 | −4.02 (72) | 0.001 |

| RAND-36 PCS | 48.7 (12.2) | 36 | 51.0 (11.8) | 38 | −7.86 to 3.27 | −0.82 (72) | 0.414 |

| RAND-36 MCS | 34.7 (8.4) | 36 | 37.7 (7.6) | 38 | −6.64 to 0.80 | −1.56 (72) | 0.122 |

MCS, mental component score; MH, mental health; PCS, physical component score; PH, physical health; PROMIS-10, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 10-Question Short Form.

Internal consistency

The PROMIS-10 demonstrated high reliabilities for both PH, Cronbach’s α=0.79, and MH, Cronbach’s α=0.83. Similar α were observed for the PROMIS-10 assessed by paper and pencil and telephone: α=0.82 and 0.81 for PH and MH, respectively, in the ’paper-and-pencil' group; α=0.77 and 0.80 for PH and MH, respectively, in the ’telephone' group.

Discussion

In this study, we used the Dutch PROMIS-10 to assess QoL in patients at 1 year after TIA or minor stroke. Our results indicate an overall strong correlation between the PROMIS-10 and the RAND-36. QoL attributed to PH was found to have a higher correlation than QoL attributed to MH. This could be explained due to PH tending to be more objective and less multidimensional in nature, whereas MH is generally more subjective and usually without an exact cause to pinpoint, which makes MH more prone to recall bias. Additionally, PH tends to be more consistent over time, while MH is more prone to fluctuations. As PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 measures self-reported health over a period in time, timing of assessment is more likely to affect MH than PH. Nonetheless, both correlations were within the range considered to be moderate to high. Bland-Altman plots demonstrated good agreement between PROMIS-10 and RAND-36. The average discrepancy between PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 was small and not clinically relevant. Visual inspection of Bland-Altman plots between PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 PH and MH revealed no obvious trends or inconsistent variability.

Subsequently, we compared two assessment methods of the PROMIS-10. Both PH and MH assessed by telephone, although slightly inferior to on-paper assessment, was found to have a strong correlation with on-paper-assessed RAND-36. No studies were found that addressed the validity of telephone assessment of the PROMIS-10. Two studies however, evaluated telephone assessment of other PROMIS measures.23 24 In line with our results, both studies provide support for telephone assessment to be reliable. One of the studies compared telephone to self-administered assessment; aside from small mode effects most likely related to study design, no apparent differences were reported as was found in our study.24 In our study, we suspect that lack of visual support when choosing a score within a range might have been contributing to a lower correlation. Other noted caveats in telephone assessment in our study were hesitation, choosing scores in between and the tendency to substantiate choices during assessment.

When comparing PROMIS-10 and RAND-36 scores between the ‘paper-and-pencil’ and ‘telephone’ group, it is notable that scores of the on-paper-assessed RAND-36 were similar in both PH and MH, whereas PROMIS-10 MH scores were significantly higher (ie, better) in the ‘telephone’ group as compared with the ‘paper-and-pencil’ group. This relatively small difference is most likely attributable to the small sample size. However, we also speculate that patients could be inclined to appear better, answer more socially desirable and are less inclined to open up about mental problems in a direct telephone interview as opposed to on-paper assessment. This speculation can be supported by findings by Perkins et al 25 and Erhart et al,26 who reported statistical significant differences for MH components in favour of telephone assessment, compared with self-administration by mail.25 26

Other possible causes for the difference between our PROMIS-10 ’telephone' and ‘paper-and-pencil’ group could be due to differences in diagnosis (TIA of minor stroke) or gender. However, subgroup analysis revealed no significant differences for both PH and MH scores between the two groups for both PROMIS-10 and RAND-36. The remaining patient characteristics obtained in this study were nearly identically distributed among both groups and are therefore unlikely to have confounded the results.

Limitations

The generalisability of our results is reduced due to our small sample size. Moreover, our study population does not cover the full range of patients who had stroke. Aside from exclusion of major stroke, as our target population were patients who had TIA and minor stroke, a large number of patients were not included as referral to the BAC based on symptoms was not indicated. Nonetheless, these relatively mildly affected patients still represent part of our target population. The same applies to patients who were excluded due to an insufficient proficiency in Dutch. In contrast to generalisability, these limitations should barely affect our results, as patient characteristics were similar among the included patients and the non-respondents.

Noteworthy is the mean (SD) of 12.5 (7.6) days between assessment of RAND-36 on paper and assessment of PROMIS-10 by telephone in our ’telephone' group. On the other hand, on-paper assessment of the PROMIS-10 is (assumed to be) completed on the same day. Health status might change over these few days. Moreover, three items of PROMIS-10 concerns the past 7 days (fatigue, emotional problems and pain).

Timing of measurement of health status in stroke should also be taken into account. We assessed the PROMIS-10 at 1 year poststroke, in contrast to the 3 months poststroke proposed by the ICHOM consensus group.13 In our current study, the 1 year poststroke period was chosen based on the results of Mierlo et al, who reported improvement of QoL occurring up to 1 year after stroke, with most changes occurring within the first 6 months.16 Another limitation is that there is no information regarding test–retest reliability of PROMIS-10 as this was only assessed at one time point.

Lastly, possible confounding factors such as individual personality traits, extent of social support, socioeconomic status and ethnicity were not accounted for in this study, while these factors undoubtedly impact self-reported QoL.

Conclusions

This study provides support for the usefullness of the Dutch version of the PROMIS-10 in patients after minor stroke or TIA in the Netherlands. Despite satisfactory validity of telephone assessment, careful interpretation is advised, especially when addressing MH status. Additional data and further research with the PROMIS-10 in patients who had stroke are desirable for establishing more firm results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all patients that have participated in the study, M Lagerwaard for data collection, the BAC-team: I Bekker, J Kramer and B Notz, for their continuous efforts in providing care for patients who had stroke, C Terwee for technical support with the PROMIS-10 and D van Rooijen for providing support in statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: K-HL and VIHK state that the following criteria for contributorship, in accordance to the ICMJE criteria for authorship, are met: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; Final approval of the version to be published; Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. In addition to being accountable for the parts of the work the authors have done, all authors are able to identify which coauthors are responsible for specific other parts of the work. In addition, the authors have confidence in the integrity of the contributions of our coauthors.

Funding: This research is funded by the Foundation Teaching Hospital OLVG, Amsterdam.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: MEC-U, Nieuwegein.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Individual participant data collected during the study that underlie the results reported in the manuscript, after deidentification (text, tables and figures), will be available for data sharing. The data will be available immediately after publication and ends 36 months after publication. The data will be available to investigators whose proposed use of the data has been approved by an independent review committee. Up to 36 months after publication, the data can be requested and accessed electronically.

References

- 1. Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, et al. Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2016;47:98–169. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Edwards DF, Hahn M, Baum C, et al. The impact of mild stroke on meaningful activity and life satisfaction. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2006;15:151–7. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2006.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arts ML, Kwa VI, Dahmen R. High satisfaction with an individualised stroke care programme after hospitalisation of patients with a TIA or minor stroke: a pilot study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2008;25:566–71. 10.1159/000132203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Muus I, Petzold M, Ringsberg KC. Health-related quality of life among Danish patients 3 and 12 months after TIA or mild stroke. Scand J Caring Sci 2010;24:211–8. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00705.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Radman N, Staub F, Aboulafia-Brakha T, et al. Poststroke fatigue following minor infarcts: a prospective study. Neurology 2012;79:1422–7. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826d5f3a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moran GM, Fletcher B, Feltham MG, et al. Fatigue, psychological and cognitive impairment following transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:1258–67. 10.1111/ene.12469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duncan PW, Samsa GP, Weinberger M, et al. Health status of individuals with mild stroke. Stroke 1997;28:740–5. 10.1161/01.STR.28.4.740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Suenkeler IH, Nowak M, Misselwitz B, et al. Timecourse of health-related quality of life as determined 3, 6 and 12 months after stroke. Relationship to neurological deficit, disability and depression. J Neurol 2002;249:1160–7. 10.1007/s00415-002-0792-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Verbraak ME, Hoeksma AF, Lindeboom R, et al. Subtle problems in activities of daily living after a transient ischemic attack or an apparently fully recovered non-disabling stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;21:124–30. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Higgins JPT, Greene S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. updated March 2011 http://handbook.cochrane.org

- 11. Porter ME. Value-based health care delivery. Ann Surg 2008;248:503–9. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818a43af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med 2010;363:2477–81. 10.1056/NEJMp1011024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salinas J, Sprinkhuizen SM, Ackerson T, et al. An International Standard Set of Patient-Centered Outcome Measures After Stroke. Stroke 2016;47:180–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care 2007;45:3–11. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Terwee CB, Roorda LD, de Vet HC, et al. Dutch-Flemish translation of 17 item banks from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS). Qual Life Res 2014;23:1733–41. 10.1007/s11136-013-0611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Mierlo ML, van Heugten CM, Post MW, et al. Quality of Life during the First Two Years Post Stroke: The Restore4Stroke Cohort Study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2016;41:19–26. 10.1159/000441197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1179–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res 2009;18:873–80. 10.1007/s11136-009-9496-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hays RD, Morales LS. The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Ann Med 2001;33:350–7. 10.3109/07853890109002089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Verhage F. Intelligence and age (in Dutch. Assen: Van Gorcum, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;1:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Field AP. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics. 4th edn London: SAGE, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Quach CW, Langer MM, Chen RC, et al. Reliability and validity of PROMIS measures administered by telephone interview in a longitudinal localized prostate cancer study. Qual Life Res 2016;25:2811–23. 10.1007/s11136-016-1325-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Magnus BE, Liu Y, He J, et al. Mode effects between computer self-administration and telephone interviewer-administration of the PROMIS(®) pediatric measures, self- and proxy report. Qual Life Res 2016;25:1655–65. 10.1007/s11136-015-1221-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Perkins JJ, Sanson-Fisher RW. An examination of self- and telephone-administered modes of administration for the Australian SF-36. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:969–73. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00088-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Erhart M, Wetzel RM, Krügel A, et al. Effects of phone versus mail survey methods on the measurement of health-related quality of life and emotional and behavioural problems in adolescents. BMC Public Health 2009;9:491 10.1186/1471-2458-9-491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.