Abstract

Introduction

Arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty is an emerging technology that has shown advantages in recovering depression of the articular surface. However, studies evaluating clinical outcomes between arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty and traditional open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) are sparse. This is the first randomised study to compare arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty with ORIF, and will provide guidance for treating patients with Schatzker types II, III and IV with depression of the medial tibial plateau only.

Methods and analysis

A blinded randomised controlled trial will be conducted and a total of 80 participants will be randomly divided into either the arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty group or the ORIF group, at a ratio of 1:1. The primary clinical outcome measures are the knee functional scores, Rasmussen radiological evaluation scores and the quality of reduction based on postoperative CT scan. Secondary clinical outcome measures are intraoperative blood loss, surgical duration, visual analogue scale score after surgery, hospital duration after surgery, complications and 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey score.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (batch: 2017–12). The results will be presented in peer-reviewed journals after completion of the study.

Trial registration number

NCT03327337, Pre-results.

Keywords: knee, adult orthopaedics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This trial is designed to have a feasible, comparative effectiveness trial design that has similarities to common clinical situations.

This study is the first randomised controlled trial to compare the outcomes of Schatzker II–IV tibial plateau fractures between arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty and traditional open reduction internal fixation in China.

Our results may be limited by heterogeneity due to differences in age, gender, region and race.

The size of the study sample limits the power of the observations.

Risk of bias due to death, loss of follow -up or uncompliant patients unable to complete tests or questionnaires.

Introduction

Tibial plateau fractures are complex intra-articular and metaphyseal lesions, accounting for 1%–2% of all fractures1 caused by either a valgus or varus force in combination with an axial force.2 The acknowledged surgical indication for a tibial plateau fracture is tilt or valgus malalignment exceeding 5°, articular step-off exceeding 3 mm, or condylar widening exceeding 5 mm (lateral tibial plateau fracture) or tilt or any displacement (medial tibial plateau fracture).3 Many classification systems have been developed for tibial plateau fractures and are used for preoperative planning and prognostic purposes.4–6 The Schatzker classification system is simple and widely used among orthopaedic surgeons in clinical practice. Schatzker II–IV tibial plateau fractures include lateral or medial depressed articular fragments, and loss of joint congruity in these injuries is associated with a poor prognosis, such as post-traumatic arthrosis and valgus deformity despite proper management. Therefore, restoration of the joint surface is the goal of surgery.7–9

Open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) for treatment of this type of fracture has yielded promising results. Gavaskar et al 10 reported that ORIF could achieve satisfactory radiological and functional results in split depression lateral tibial plateau fractures. After ORIF for 15 cases of medial tibial plateau fractures, Morin et al 11 reported that 93% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with their functional recovery and there were no cases of pseudarthrosis or secondary varus displacement. However, traditional ORIF treatment has a number of disadvantages, for example, excessive damage, limited exposure of the articular cavity and insufficient ability to diagnose and address internal joint injury.12

With recent technological advances, the treatment concept of tibial plateau fractures has progressed from mechanical fixation to minimally invasive surgical interventions for biomechanical stability.13 14 Based on the success of vertebral kyphoplasty, arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty15 has been developed as a novel, minimally invasive technique for reducing depressed tibial plateau fractures. Arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty is an emerging technology that aims to visualise the articular surface, and uses balloon distension tibial plasty assisted by arthroscopy to recover depression of the articular surface and fix the fracture according to its specific type.16 This technology has shown advantages in recovering depression of the articular surface,17 treating additional intra-articular lesions during the operation and minimising surgical trauma. Furthermore, under fluoroscopy, optimal centring of the expanding tibioplasty balloon allows a widespread and continuously increasing reduction force to be applied to the fracture area.18 Primary data from Ollivier et al 19 showed that depressed tibial plateau fractures treated with arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty had a high rate of anatomic reduction and good clinical outcomes. Similar results were also reported by Pizanis et al 15 using arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty without classic fenestration of the tibia, which would minimise surgical trauma. However, a number of factors influence the clinical adoption of this surgical technique: the application time is short, there is a paucity of case data and information regarding long-term follow-up and the cost of operation is higher than traditional ORIF.20

To our knowledge, there have been no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of the clinical outcomes of arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty versus ORIF, where high-quality RCTs are generally deemed to be the gold standard in clinical research. In this study, we will perform an RCT to compare arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty and traditional ORIF.

Methods and design

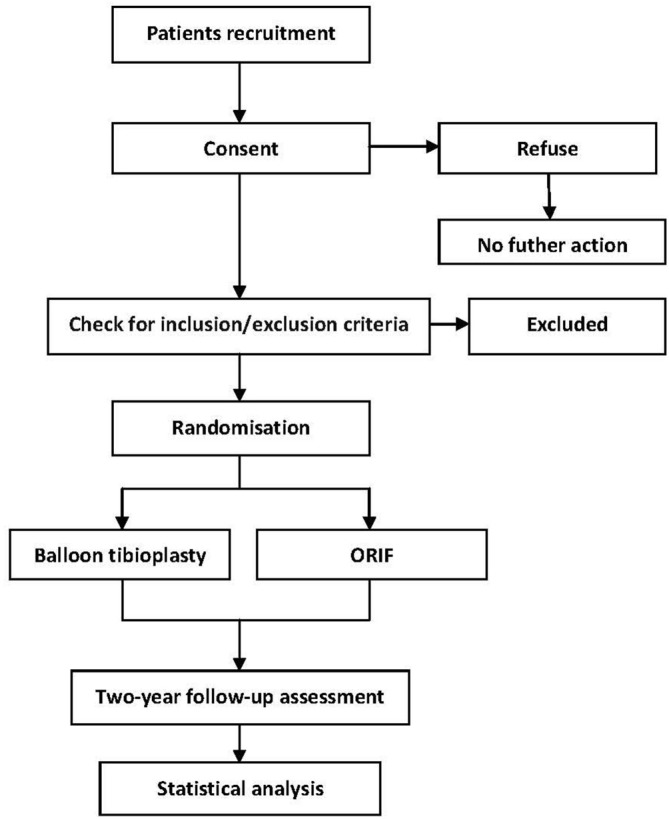

This study has been approved, and conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients will provide informed consent prior to participation in this study. This trial has been registered at the US National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials Registry (NCT03327337). The protocol conforms to the Standard Protocol Items Recommendations for Interventional Trials. Figure 1 shows a chart of the trial design.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the steps in participant recruitment, treatment and analysis. Balloon tibioplasty, arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty group; ORIF, open reduction and internal fixation group.

Participants

This study is a parallel group RCT conducted at the Department of Orthopaedics, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. Fractures will be evaluated on anteroposterior and laterolateral radiographs and by CT, which can analyse the fracture pattern more precisely.

Inclusion criteria

Acute closed fractures less than 10 days old, and X-ray and CT scan showing Schatzker types II, III or IV with depression of the medial tibial plateau only (see online supplementary information S1).

No history of knee joint dislocation or other knee traumas.

Signed informed consent.

Age of 18–80 years.

bmjopen-2018-021667supp001.pdf (245.2KB, pdf)

Exclusion criteria

Other types of tibial plateau fracture (Schatzker types I, IV with split or comminuted fracture, V and VI).

Concomitant injuries that will interfere with functional recovery, such as combined fracture of the lower limb.

Open fractures, pathological fractures, immunodeficiency, haematological diseases or severe hepatorenal disorders.

Patient involvement

The design of this study was not directly involved in the patients, and the intervention in this study is not considered to change the patient’s direct perception of the preoperative and intraoperative processes or the postoperative rehabilitation therapy. As the enrolment in the study may influence the patient’s view of the clinical work or even feel like a burden, the patients will be interviewed randomly to identify adverse effects. The results will be informed by mail to all the patients involved.

Randomisation and blinding

Prerandomisation eligibility checks will be carried out to ensure that participants are eligible for inclusion in the study. Patients will be randomly assigned to one of two groups (experimental or control) using a computer-generated random assignment in a 1:1 ratio, and allocation will be concealed until the point of randomisation. Patients, researchers performing the follow-up measurements and the trial statistician will be blinded to the group allocations until the last questionnaires have been completed.

Interventions

Arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty group

Step 1

In cases with a splitting tibial plateau fracture (Schatzker type II), an incision will be made in the proximal tibia according to the fracture type, for placement of a small locking T-plate (Synthes, Freiburg, Germany) using minimally invasive techniques. Then, a temporary cortical bone screw will be inserted to prevent cortical rupture when the balloon is enlarged. Temporary fixation of the cortical bone screw will permit further adjustment of the position of the plate. In cases with no splitting tibial plateau fracture (Schatzker types III or IV with depression of the medial tibial plateau only), we will proceed to step two directly.

Step 2

Three Kirschner wires (2 mm) will be placed below the depressed fragment under fluoroscopy. Using live fluoroscopy, the balloon will be placed in the optimal position and slowly inflated with contrast solution (Ultravist, Schering, Berlin, Germany). The arthroscope will then be used to confirm anatomical reduction of the depressed fragment. The balloon will be deflated, repositioned and reinflated to reduce the persistent depression. After removal of the balloon, we will use a Kirschner wire (2 mm) to temporarily lift the depressed fragment and carefully inject calcium phosphate cement (Osteopal V; Heraeus Medical GmbH, Wehrheim, Germany) into the cavity produced by the balloon under fluoroscopic guidance, ensuring there is no excessive cement overflow into the tibial medullary cavity (see online supplementary information S2).

ORIF group

For this technique, a lateral or medial surgical approach will be used according to the type of fracture. The depressed fragment will be elevated by a metal tamp through a small cortical window in the proximal tibia, and bone substitute will be used. Finally, internal fixation will be performed when an acceptable reduction has been achieved.

If satisfactory reduction cannot be achieved using arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty, patients will undergo ORIF and will be excluded from the study. All patients will receive rehabilitation therapy regardless of the group to which they are allocated, and progressive partial weight-bearing will be permitted with the aid of two crutches. Postoperative CT scans will be performed immediately, and at 2 weeks and 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 months, and Rasmussen radiological evaluation will be performed.21 To evaluate functional recovery of the knee joint and health-related quality of life, all patients will complete the Rasmussen functional score and 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaires during the follow-up period. Scoring will performed by two researchers who were not involved in the initial treatment.

Outcome measurements

Primary outcome measure

Knee functional recovery will be assessed by the Rasmussen functional score, which will be recorded at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months postoperatively.

Rasmussen radiological evaluation will be recorded immediately, and at 2 weeks and 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 months postoperatively.

The quality of reduction will be determined based on postoperative CT scans, which can directly measure the amount of residual depression, at 2 weeks and 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 months postoperatively.

Secondary outcome measures

Intraoperative blood loss will be recorded in the anaesthesia records, and will include the blood in suction bottles (after subtracting the lavage fluid used during the surgery), and that in the weighed sponges used during the operation.

Surgical duration.

The severity of lower limb pain after surgery will be assessed using a visual analogue scale (VAS) pain score. The VAS scores of leg pain will be recorded from the day of the operation to the day of discharge from hospital (up to 2 weeks).

Hospitalisation period after surgery.

-

Complications including wound infection (defined as minor, major, early or late according to the criteria described by the Surgical Infection Study Group22), reoperations and post-traumatic arthritis (PTA) will be recorded.

PTA may not be seen in patients within the 24-month follow-up period, and we will perform follow-up for at least 10 years in all patients.

-

Health-related quality of life will be measured using the SF-36 questionnaire during follow-up.

The SF-36 is a health-related quality of life questionnaire used to assess both the mental and physical health of the patient.

Baseline demographics

Sex, age, body mass index, mechanism of injury, smoking status, alcohol use and comorbidities (ie, hypertension, diabetes, cardiopathy).

Follow-up

Follow-up will be conducted at 2 weeks and 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 months postoperatively.

Monitoring

All investigators who have completed training are capable of independently collecting the data and assessing the clinical outcomes, and all electronic data will be recorded by an electronic data capture system (DAP Software Company, Beijing, China). Safety and data monitoring will be performed periodically during the study. All paper and electronic data will be stored for 10 years in the secure research archives at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, with restricted access.

Sample size calculation

There have been no previous studies on which to base the sample size calculation. In a related study,21 the excellent Rasmussen radiological evaluation proportion of the control group was 60%, and the proportion of the intervention group was 70%. We carried out power analysis to determine the sample size required to show safety with a type I error probability of 5% and an 80% probability of avoiding a type II error. Using these assumptions, the required sample size is 35 per group. With the assumption of a 12.5% loss to follow-up, we will include 40 participants per group.

Statistical analysis

The trial data will be analysed using SPSS for Windows software (V.19.0; SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). For continuous variables, the Shapiro-Wilk test will be applied to determine if they follow a normal distribution. For normally distributed variables, the means will be calculated and compared using the independent samples t-test (Student’s t-test); otherwise, the Mann-Whitney U test will be used for group comparisons. The χ2 test will be used to analyse qualitative variables. In all analyses, p<0.05 will be taken to indicate statistical significance.

Discussion

There have been a number of reports describing treatment for tibial plateau fractures. In a systematic review of the treatment of tibial plateau fractures, Metcalfe et al 23 suggested that ORIF and external fixation are both acceptable strategies for managing bicondylar tibial plateau fractures, with no statistically significant differences found in the rates of complications between the two methods. In addition, after a systematic review of all studies reporting return to sport following tibial plateau fracture, Robertson et al 24 reported that the rate of return to sport for the total cohort was 70%, versus 60% for those with fractures managed with ORIF and 83% for fractures treated with arthroscopic-assisted reduction internal fixation (OR 3.22, 95% CI 2.09 to 4.97, p<0.001).

An ideal treatment method for Schatzker II–IV tibial plateau fracture has to achieve anatomical restoration of the knee joint and rigid fixation to allow early postoperative rehabilitation.25 Traditional ORIF requires extensive soft tissue dissection, which may lead to numerous negative outcomes such as slow wound healing, infection and PTA.26 Due to limited exposure, intra-articular lesions, such as meniscus or anterior cruciate ligament injuries, cannot be diagnosed and treated properly.27 Ruffolo et al 28 reported that non-union and deep infections occur commonly after ORIF, and long surgical durations are associated with higher rates of infection. With the development of arthroscopic techniques, arthroscopy-assisted reduction and internal fixation (ARIF) has been widely adopted in the treatment of tibial plateau fractures,29 and has shown good functional recovery and radiological results.30–32 After comparing the Rasmussen and Hospital for Special Surgery knee-rating scores between ARIF and ORIF, Dall’oca et al 12 reported that the ARIF technique improved the clinical outcome in Schatzker types II–IV fractures. Balloon tibioplasty is an arthroscopic-assisted minimally invasive technique that creates a symmetrical, contained defect to hold bone filler for subchondral support; the balloon also allows to eliminate the neurological and vascular risks of the conventional approach.20 This technique has already been used for kyphoplasty and maxillofacial surgery, and has recently been applied for tibial plateau fractures.15 19 33 Mauffrey et al 20 reported early positive results with arthroscopy-assisted balloon tibioplasty used as an alternative reduction method, and the method is gaining acceptance. This paper describes the protocol for conducting an RCT in China that will investigate the efficacy of arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty in treating Schatzker II–IV tibial plateau fractures. The design of this trial included an ORIF group as a control group, to compare the clinical outcomes of Schatzker II–IV tibial plateau fractures with those of arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty fixation. Arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty is hypothesised to be superior in reducing surgical trauma, and to have better clinical outcomes in comparison with ORIF. This study is the first RCT to compare the outcomes of Schatzker II–IV tibial plateau fractures between arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty and traditional ORIF in China. If our hypothesis is confirmed, our results will be important for informing the scheduling and development of treatment options for Schatzker II–IV tibial plateau fracture surgery. We anticipate that the results will provide reliable evidence and clarify the value of arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty as a treatment for patients with Schatzker II–IV tibial plateau fractures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the physiotherapists for their collaboration on establishing a postoperative rehabilitation therapy for all patients involved in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: J-QW helped to design the trial and wrote the manuscript. B-JJ helped to design the trial. W-JG helped to conceive the trial and revised the manuscript. W-JZ recruited the patients and conducted the trial. A-BL planned the statistical analysis. Y-MZ helped to design the study and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by Clinical Scientific Research Project of the Second Affiliated Hospital of the Wenzhou Medical University (SAHoWMU-CR2017-08-105).

Disclaimer: The funders had no role in the design, execution or writing of the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study had been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of the Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, China (batch: 2017-12).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. McNamara IR, Smith TO, Shepherd KL, et al. Surgical fixation methods for tibial plateau fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;240:Cd009679 10.1002/14651858.CD009679.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mayr R, Attal R, Zwierzina M, et al. Effect of additional fixation in tibial plateau impression fractures treated with balloon reduction and cement augmentation. Clin Biomech 2015;30:847–51. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Honkonen SE. Indications for surgical treatment of tibial condyle fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994;302:199–205. 10.1097/00003086-199405000-00031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maripuri SN, Rao P, Manoj-Thomas A, et al. The classification systems for tibial plateau fractures: how reliable are they? Injury 2008;39:1216–21. 10.1016/j.injury.2008.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Doornberg JN, Rademakers MV, van den Bekerom MP, et al. Two-dimensional and three-dimensional computed tomography for the classification and characterisation of tibial plateau fractures. Injury 2011;42:1416–25. 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen P, Shen H, Wang W, et al. The morphological features of different Schatzker types of tibial plateau fractures: a three-dimensional computed tomography study. J Orthop Surg Res 2016;11:94 10.1186/s13018-016-0427-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen HW, Liu GD, Wu LJ. Clinical and radiological outcomes following arthroscopic-assisted management of tibial plateau fractures: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015;23:3464–72. 10.1007/s00167-014-3256-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Egol KA, Cantlon M, Fisher N, et al. Percutaneous Repair of a Schatzker III Tibial Plateau Fracture Assisted by Arthroscopy. J Orthop Trauma 2017. 31 Suppl 3:S12–S13. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Craiovan BS, Keshmiri A, Springorum R, et al. [Minimally invasive treatment of depression fractures of the tibial plateau using balloon repositioning and tibioplasty: video article]. Orthopade 2014;43:930–3. 10.1007/s00132-014-3019-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gavaskar AS, Gopalan H, Tummala NC, et al. The extended posterolateral approach for split depression lateral tibial plateau fractures extending into the posterior column: 2 years follow up results of a prospective study. Injury 2016;47:1497–500. 10.1016/j.injury.2016.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morin V, Pailhé R, Sharma A, et al. Moore I postero-medial articular tibial fracture in alpine skiers: Surgical management and return to sports activity. Injury 2016;47:1282–7. 10.1016/j.injury.2016.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dall’oca C, Maluta T, Lavini F, et al. Tibial plateau fractures: compared outcomes between ARIF and ORIF. Strategies Trauma Limb Reconstr 2012;7:163–75. 10.1007/s11751-012-0148-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kampa J, Dunlay R, Sikka R, et al. Arthroscopic-Assisted Fixation of Tibial Plateau Fractures: Patient-Reported Postoperative Activity Levels. Orthopedics 2016;39:e486–e491. 10.3928/01477447-20160427-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lasanianos NG, Garnavos C, Magnisalis E, et al. A comparative biomechanical study for complex tibial plateau fractures: nailing and compression bolts versus modern and traditional plating. Injury 2013;44:1333–9. 10.1016/j.injury.2013.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pizanis A, Garcia P, Pohlemann T, et al. Balloon tibioplasty: a useful tool for reduction of tibial plateau depression fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2012;26:e88–93. 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31823a8dc8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ziogas K, Tourvas E, Galanakis I, et al. Arthroscopy Assisted Balloon Osteoplasty of a Tibia Plateau Depression Fracture: A Case Report. N Am J Med Sci 2015;7:411–4. 10.4103/1947-2714.166223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jentzsch T, Fritz Y, Veit-Haibach P, et al. Osseous vitality in single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) after balloon tibioplasty of the tibial plateau: a case series. BMC Med Imaging 2015;15:56 10.1186/s12880-015-0091-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Di Caprio F, Buda R, Ghermandi R, et al. Combined arthroscopic treatment of tibial plateau and intercondylar eminence avulsion fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):161–9. 10.2106/JBJS.J.00812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ollivier M, Turati M, Munier M, et al. Balloon tibioplasty for reduction of depressed tibial plateau fractures: Preliminary radiographic and clinical results. Int Orthop 2016;40:1961–6. 10.1007/s00264-015-3047-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mauffrey C, Roberts G, Cuellar DO, et al. Balloon tibioplasty: pearls and pitfalls. J Knee Surg 2014;27:31–7. 10.1055/s-0033-1363516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elabjer E, Benčić I, Ćuti T, et al. Tibial plateau fracture management: arthroscopically-assisted versus ORIF procedure - clinical and radiological comparison. Injury 2017. 48 Suppl 5:S61–S64. 10.1016/S0020-1383(17)30742-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peel AL, Taylor EW. Proposed definitions for the audit of postoperative infection: a discussion paper. Surgical Infection Study Group. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1991;73:385–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Metcalfe D, Hickson CJ, McKee L, et al. External versus internal fixation for bicondylar tibial plateau fractures: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Traumatol 2015;16:275–85. 10.1007/s10195-015-0372-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Robertson GAJ, Wong SJ, Wood AM. Return to sport following tibial plateau fractures: A systematic review. World J Orthop 2017;8:574–87. 10.5312/wjo.v8.i7.574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rossi R, Bonasia DE, Blonna D, et al. Prospective follow-up of a simple arthroscopic-assisted technique for lateral tibial plateau fractures: results at 5 years. Knee 2008;15:378–83. 10.1016/j.knee.2008.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rademakers MV, Kerkhoffs GM, Sierevelt IN, et al. Operative treatment of 109 tibial plateau fractures: five- to 27-year follow-up results. J Orthop Trauma 2007;21:5–10. 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31802c5b51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen XZ, Liu CG, Chen Y, et al. Arthroscopy-assisted surgery for tibial plateau fractures. Arthroscopy 2015;31:143–53. 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ruffolo MR, Gettys FK, Montijo HE, et al. Complications of high-energy bicondylar tibial plateau fractures treated with dual plating through 2 incisions. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29:85–90. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chan YS, Yuan LJ, Hung SS, et al. Arthroscopic-assisted reduction with bilateral buttress plate fixation of complex tibial plateau fractures. Arthroscopy 2003;19:974–84. 10.1016/j.arthro.2003.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chiu CH, Cheng CY, Tsai MC, et al. Arthroscopy-assisted reduction of posteromedial tibial plateau fractures with buttress plate and cannulated screw construct. Arthroscopy 2013;29:1346–54. 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ruiz-Iban MA, Diaz-Heredia J, Elias-Martin E, et al. Cebreiro Martinez Del Val I (2012) Repair of meniscal tears associated with tibial plateau fractures: a review of 15 cases. The American journal of sports medicine;40:2289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gill TJ, Moezzi DM, Oates KM, et al. Arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation of tibial plateau fractures in skiing. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;383:243–9. 10.1097/00003086-200102000-00028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Doria C, Balsano M, Spiga M, et al. Tibioplasty, a new technique in the management of tibial plateau fracture: A multicentric experience review. J Orthop 2017;14:176–81. 10.1016/j.jor.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-021667supp001.pdf (245.2KB, pdf)