Abstract

Objective

The lack of coordinated and appropriate healthcare across sectors has produced more patients for county hospitals in China. This study examined differences in patient choice between township and county hospitals for readmission after a first township hospitalisation, and the determinants that influenced this choice.

Design

A retrospective study of readmissions across hospitals after a first admission in township hospital. A township–township (TT) inpatient group and a township–county (TC) inpatient group were compared. A two-level logistic regression model was used to examine the determinants of choice for hospital readmission.

Setting

Data were drawn from a population-based health utilisation database for Qianjiang District, China, from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2013.

Participants

This study focused on readmitted patients whose first admission was in a township hospital. Readmission cases were identified as the same diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision) in a subsequent hospitalisation within 30 days. In total, 6764 readmissions had first admissions in township hospitals.

Primary outcome measures

Patient choice for hospital readmission after a first township hospitalisation.

Results

The TT group accounted for 62.5% (4225) and the TC group for 37.5% (2539) of readmissions in 6 years, and the proportion of TC readmissions in total inpatients increased from 1.66% to 1.89%. Readmission rates varied among towns (p<0.001). Differences between the TC and TT groups included: length of stay (LOS) of first admission (6.96 days vs 9.23 days), average interval between admissions (6.03 days vs 14.95 days) and disease category. Admission year, age, travel time to county hospital, interval between admissions, first admission LOS and disease category were determinants of choice for hospital readmission.

Conclusions

Patients whose first admission was in a township hospital were more likely to be readmitted to a county hospital. A combination of first LOS and interval between admissions may be an effective identification index for TC readmission.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR-OOR-14005563.

Keywords: readmission, choice, county hospital, patient flow, rural China

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to focus on township–county readmission, a feature of hospitalisation in rural China.

Population-level data on readmission are seldom reported across hospitals of different levels.

Programming techniques, including Microsoft Excel formulas and case processing technologies, were used in the data processing.

A two-level logistic regression model was used to consider aggregation at the town level.

Hospitalisation information, geographical factors, interval status and disease were all entered into the logistic regression model, but some individual factors were missing.

Background

Readmission refers to an episode where an inpatient is readmitted for the same disease within 30 days.1 2 In most studies, readmission findings reflect that inpatient care did not meet patient requirements, with readmission rates used as an evaluation index for hospitalisation quality.3 Readmission usually occurs in the same hospital, but sometimes occurs across hospitals because of deterioration of a patient’s disease.4 However, in rural China, multilevel institutional readmission is a common and important healthcare utilisation. This reflects defects of China’s healthcare delivery system, rather than hospitalisation quality, especially in township–county (TC) readmissions. TC readmission is a health-seeking behaviour in which inpatients seek healthcare services in a township hospital first, and then in a county hospital, whether planned or unplanned, voluntarily or passively. TC readmission is frequent in rural China, and currently accounts for approximately 2.0% of all inpatient services.5 TC readmission usually occurs following doctor recommendation/referral or by individual patient choice.

TC readmission recommended by doctors occurs when a township doctor has an inpatient admission that they cannot fully treat or completely cure;6 consequently, that patient is referred directly to a county hospital or advised to go to a county hospital for subsequent admission.6 This situation results from the three-tier healthcare delivery system in rural China, where care is provided in a village–town–county healthcare delivery system, and all hospital services are supplied by township and county hospitals.7 In general, the higher the level of the institution, the stronger the service capability, the greater the distance a patient must travel and the higher the medical cost. Township hospitals bear the responsibilities of transferring patients, taking care of inpatients with general illnesses and advising patients with severe diseases (that are beyond their capacity) to seek admission at county hospitals.8 Township hospital doctors sometimes receive patients whose diseases are beyond their capacity to manage (eg, because of their inaccurate judgement, or deterioration of the disease), meaning TC readmission may be unavoidable.

TC readmission from individual choice may occur when patients who should be readmitted to township hospitals choose to be admitted to county hospitals for personal reasons.9 Some readmissions are influenced by quality concerns with township hospitals, poor patient compliance on medicine and aftercare or from a normal disease recurrence. However, patients often do not acknowledge the real readmission reason and transfer responsibility for readmission to the township hospital doctor (eg, considering readmission as a result of failed treatment) and consequently decide to be readmitted to a county hospital. This situation often represents inappropriate readmission.10

From the patients’ perspective, no order or limitation on patient choice exists. In addition, no general practitioners or consultants are available in rural China. Therefore, residents freely choose hospitals and service types, mainly depending on their judgement regarding their disease and understanding of hospitals. If a patient chooses a higher-level institution than necessary, they pay more; if they choose a lower-level institution than necessary, they would be referred or readmitted. Therefore, the cost of an incorrect decision is borne by the patient. To guarantee patient interests regarding TC readmission, the three-tier healthcare delivery system requires different-level hospitals to cooperate in providing continuous healthcare services. However, in reality, communication among township and county professional providers is limited, and there is virtually no document sharing or interaction among providers across the three tiers.11 County hospital doctors do not deliver continued care for readmitted patients because of income incentives and risk aversion, and patients readmitted to a county hospital usually receive new treatment.12 Furthermore, compared with patients admitted directly to county hospitals, readmitted patients spend more time, pay more costs and may even miss proper treatments. As a result, when subsequent illnesses occur and patients are unable to judge the severity of their illness, they tend to choose admission in a county hospital, taking excess economic risk to avoid delay. Some studies have defined TC readmission as failed treatment from the patients’ perspective, and have shown that the TC readmission experience can influence a patient’s later choice of hospital.13 14 Inpatients may be more likely to seek care in county hospitals compared with township hospitals, a phenomenon that is already happening. The annual growth rate of inpatients in county hospitals from 2010 to 2016 was 6.75%, whereas that of township hospital inpatients was 0.63% in rural China.15

As noted, TC readmission from individual choice may be an inappropriate level of admission, and TC readmission recommended by doctors can also result in inappropriate level admission for subsequent hospitalisation. Inappropriate level admission means patients seek healthcare in a higher-level hospital than necessary. This may result from patients’ intentional institution selection and distrust of the capability of township hospitals; such patients prefer to spend more money on healthcare to avoid the risk of needing referral. Inappropriate level admission is a major form of excess service demand,12 and an important determinant of increasing health expenditure that leads to significant waste.

In this context, identifying the forms and determinants of TC readmission will help to improve the New Rural Cooperative Medical System (NRCMS). This study focused on choices for hospital readmission after a first admission as an inpatient in a township hospital, and identified the determinants of choice for hospital readmission.

Methods

Study setting

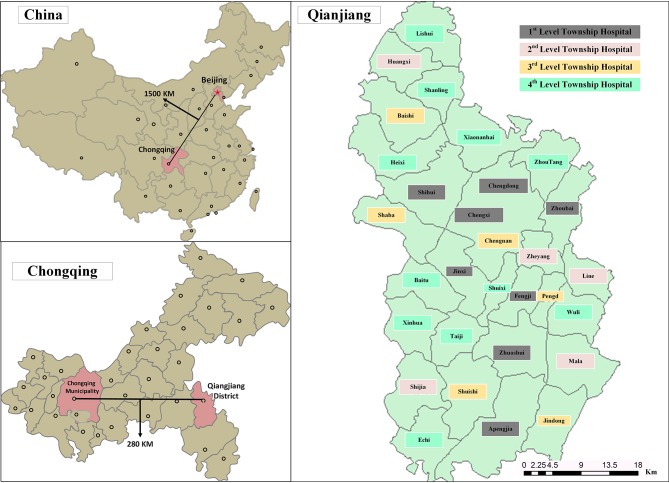

Qianjiang District was designated as the sample area through cluster sampling. This is a typical rural area located in Chongqing, which is the largest municipality in southwest China. Qianjiang has a per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of $7515 in 2016, which is below the average GDP in China. The resident population is 550 000 people; all residents are covered under the NRCMS, and are eligible to receive reimbursement for inpatient care. Qianjiang District has two county hospitals and 30 township hospitals. The township hospitals are divided into four levels according to their scale and service quantity by Qianjiang Health Bureau (figure 1). First-level township hospitals are allocated more than 30 beds and may perform abdominal operations; these hospitals had more than 1200 discharged patients in 2013. Second-level township hospitals cannot perform abdominal operations of the same scale as first-level township hospitals. Third-level township hospitals have fewer than 30 beds and around 600~1200 discharged patients. All other township hospitals belong to the fourth level.

Figure 1.

Map of Qianjiang District: geographic distribution.

Data source

This study was based on the NRCMS inpatient database in Qianjiang District, which contains all inpatient data for the population. In this database, a case refers to a single hospitalisation in a county or township hospitals.

Data processing

We focused on individuals who had been discharged from participating hospitals. Readmission cases were identified as having the same diagnosis in subsequent hospitalisations between county and township hospitals or township hospitals and township hospitals within 30 days. Given our population-based retrospective design, we compared the differences between township–township readmitted inpatients (TT group) and TC readmitted inpatients (TC group). Samples were entered into MS Excel 2010, based on the NRCMS database from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2013. First, cases that shared the same patient identifier and the same disease codes were sorted in chronological order. Second, we calculated the interval between admissions in two adjacent cases for the same inpatient for the same disease; if the interval between admissions was less than 31 days, the patient was marked as a readmission patient. For example, if the first admission occurred in a township hospital and the second occurred in county hospital, the two cases would be merged as one case and marked as a TC readmission, and the patient marked as TC patient. TT patients were identified in a similar manner. Finally, all TC and TT cases were extracted into a new database. As diagnosis of a disease may change among different doctors, in different institutions or at different times, we adjusted the original International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision disease code into a broader code (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was adjusted from J44.900 to J44), which may improve accuracy in identifying readmitted patients. After screening, there were 6764 readmitted patients from 2008 to 2013 in the sample.

The main programming techniques included Microsoft Excel formulas (eg, COUNTIF, SUMPRODUCT, LOOKUP and IF) and case processing technologies (eg, split columns and removal of duplicates).

Sociological characteristics were collected to build a final database, including: gender; age; travel time from home to county hospital; first inpatient information including length of stay (LOS), expenses, disease category, capacity of the township hospital, interval between admissions and readmitted hospital choice.16 The distance and travel time to the county hospital for all readmitted patients were captured individually by Google Maps. Because traffic conditions are different in different towns (eg, national roads, provincial roads or county roads), both the distance and travel time were captured.

Data obtained and statistical analysis

The characteristics of patients’ choices for hospital readmission were compared using t-tests and χ2 tests in IBM SPSS Statistics V.22.0. The treatment capacity of township hospitals and the travel time to a county hospital from different towns have differential impacts on the observed predictors. Therefore, we assumed that the obtained data indicated a hierarchical structure, and the 6764 records could be aggregated by town level. The determinants of choice for hospital readmission were examined using multilevel binomial logistic regression analysis using MLwiN V.2.30, which was developed by the University of Bristol, UK.17 Patients were identified as level 1 and town as level 2. The regression model was as follows.

βi refers to the fixed effects parameter, and uoj refers to the random effects of level 2.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or public were involved in this research.

Ethical approval

The study protocol conformed to the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of the Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The protocol was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR-OOR-14005563). Patient information was anonymised and deidentified before analysis.

Results

Choices for hospital readmission after a first township hospitalisation

Among 271 405 discharged admissions in 2008–2013, there were 6764 readmissions after a first hospitalisation in a township hospital. The TT group accounted for 62.5% (4225) of all readmissions and the TC group for 37.5% (2539) (table 1). The number of readmissions increased sharply, whereas the proportion of readmissions in the total inpatients averaged around 5%. The TC group increased from 1.66% in 2008 to 1.89% in 2013, with the annual growth rate of the TC group being 28.55%, which was higher than that of the TT group (22.38%).

Table 1.

Number of readmissions each year in Qianjiang District (2008–2013)

| Year | All inpatients | Readmissions* n (%) |

Choice for hospital readmission† | P values‡ | |

| TT group n (%) | TC group n (%) | ||||

| 2008 | 21 823 | 524 (4.80) | 342 (3.14) | 182 (1.66) | <0.001 |

| 2009 | 34 240 | 1076 (6.27) | 724 (4.23) | 352 (2.04) | |

| 2010 | 35 866 | 942 (5.25) | 608 (3.39) | 334 (1.86) | |

| 2011 | 50 616 | 1260 (4.98) | 797 (3.16) | 463 (1.82) | |

| 2012 | 61 467 | 1384 (4.50) | 815 (2.64) | 569 (1.86) | |

| 2013 | 67 392 | 1578 (4.67) | 939 (2.78) | 639 (1.89) | |

| Total | 271 405 | 6764 (4.98) | 4225 (3.11) | 2539 (1.87) | |

*Readmission refers to readmissions whose first admission was in a township hospital.

†One readmission includes two admissions.

‡Pearson’s χ2 test.

TC, township–county; TT, township–township.

Readmission varied among towns (table 2). Chengnan town had the lowest overall readmission ratio (2.95%) and the lowest TT readmission ratio (1.52%) of the 30 towns. Heixi town had the lowest TC readmission ratio (1.30%), Shijia town had the highest TC readmission ratio (2.86%) and Jindong town had the highest TT readmission (5.49%) and overall readmission (6.96%) ratios.

Table 2.

Number of readmissions in Qianjiang District (2008–2013), by town

| Town | All inpatients | Readmissions* n (%) |

Choice for hospital readmission† | P values‡ | |

| TT group n (%) | TC group n (%) | ||||

| Chengnan | 11 716 | 173 (2.95) | 89 (1.52) | 84 (1.43) | <0.001 |

| Heixi | 9073 | 137 (3.02) | 78 (1.72) | 53 (1.30) | |

| Shaba | 8778 | 152 (3.20) | 81 (1.58) | 71 (1.62) | |

| ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | |

| Shijia | 8605 | 223 (5.18) | 100 (2.32) | 123 (2.86) | |

| Jindong | 6007 | 209 (6.96) | 165 (5.49) | 44 (1.47) | |

| Total | 2 71 405 | 6764 (4.98) | 4225 (3.11) | 2539 (1.87) | |

*Readmission refers to readmissions whose first admission was in a township hospital.

†One readmission includes two admissions.

‡Pearson’s χ2 test.

TC, township–county; TT, township–township.

Characteristics of readmitted patients between TT and TC groups

Table 3 shows the characteristics of readmitted patients from 2008 to 2013. Male patients accounted for 48.7% of the TC group, which was a higher rate than in the TT group (41.9%, p<0.001). Readmission choices varied in different age groups (p<0.001), with over half (57.9%) of patients in the TC group aged 40–59 years. The most common interval between admissions in the TC group was shorter than 3 days (61.1%), whereas that in the TT group was 16–30 days (50.6%, p<0.001). The average interval between admissions in the TC group was lower than that in TT group (6.03 days vs 14.95 days). Similar patterns were observed in the average LOS of first inpatient admissions (6.96 days vs 9.23 days) and travel time to county hospital (59.73 min vs 61.79 min). However, an opposite trend was observed in terms of expenses of first inpatient admission (¥831.35 vs ¥791.01). The TC group mostly had respiratory (37.7%) and digestive diseases (20.3%). There were no significant differences in the distance to a county hospital and the township hospital capacity between the TT and TC groups.

Table 3.

Distribution of characteristics of readmitted patients (n=6764)

| Variable | All n (%) | Choice for hospital readmission | P values | |

| TT group n (%) | TC group n (%) | |||

| All | 6764 | 4225 (62.5) | 2539 (37.5) | |

| Gender | <0.001* | |||

| Male | 3006 (44.4) | 1769 (41.9) | 1237 (48.7) | |

| Female | 3758 (55.6) | 2456 (58.1) | 1302 (51.3) | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 48.18 (0.27) | 46.94 (0.35) | 50.25 (0.43) | <0.001† |

| Less than 20 | 950 (22.0) | 629 (22.9) | 321 (20.5) | <0.001* |

| 20–39 | 1215 (28.2) | 877 (31.9) | 338 (21.6) | |

| 40–59 | 2045 (47.4) | 1192 (43.4) | 853 (54.4) | |

| More than 59 | 103 (2.4) | 48 (1.7) | 55 (3.5) | |

| Distance to CH (km) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 36.29 (0.27) | 35.99 (0.34) | 36.78 (0.42) | 0.15† |

| Time to CH (min) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 60.51 (0.45) | 59.73 (0.57) | 61.79 (0.72) | 0.03† |

| Capacity of TH | 0.53* | |||

| First level (Strong) | 3076 (45.5) | 1918 (45.4) | 1158 (45.6) | |

| Second level (Better) | 1315 (19.4) | 802(19) | 513 (20.2) | |

| Third level (General) | 935 (13.8) | 591(14) | 344 (13.5) | |

| Fourth level (Weak) | 1438 (21.3) | 914 (21.6) | 524 (20.6) | |

| First LOS (day) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 8.38 (0.12) | 9.23 (0.16) | 6.96 (0.16) | <0.001† |

| First expense (RMB) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 816.21 (7.94) | 831.35 (9.95) | 791.01 (13.14) | 0.01† |

| Second LOS (day) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.24 (0.13) | 10.03 (0.16) | 10.58 (0.22) | 0.04† |

| Second expense (RMB) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2215.49 (45.46) | 862.99 (12.77) | 4466.09 (104.99) | <0.001† |

| Interval between admissions (day) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 11.6 (0.12) | 14.95 (0.14) | 6.03 (0.17) | <0.001† |

| ~3 | 2133 (31.5) | 582 (13.8) | 1551 (61.1) | <0.001* |

| 3–7 | 761 (11.3) | 517 (12.2) | 244 (9.6) | |

| 7–15 | 1328 (19.6) | 987 (23.4) | 341 (13.4) | |

| 16–31 | 2542 (37.6) | 2139 (50.6) | 403 (15.9) | |

| Disease category | <0.001* | |||

| Cancer | 178 (2.6) | 109 (2.6) | 69 (2.7) | |

| ENT disease | 338 (5.0) | 243 (5.8) | 95 (3.7) | |

| Respiratory disease | 2673 (39.5) | 1715 (40.6) | 958 (37.7) | |

| Circulatory disease | 450 (6.7) | 224 (5.3) | 226 (8.9) | |

| Digestive disease | 984 (14.5) | 469 (11.1) | 515 (20.3) | |

| Urinary disease | 269 (4.0) | 89 (2.1) | 180 (7.1) | |

| Haematological disorders | 19 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 17 (0.7) | |

| Bones and muscles | 425 (6.3) | 218 (5.2) | 207 (8.2) | |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 1213 (17.9) | 1037 (24.5) | 176 (6.9) | |

*Pearson’s χ2 test.

†Analysis of variance.

CH, county hospital; ENT, ears, nose and throat; LOS, length of stay; TC, township–county; TH, township hospital; TT, township–township.

Determinants of choice for hospital readmission after township hospitalisation

The two-level logistic regression is illustrated by the level 2 variance of the zero model. This was statistically significant (χ2 = 63.524, p<0.001), with aggregation of information at the town level. The specific results of the explanatory variables to fit the two variance component model are shown in table 4. The major determinants of the choice for hospital readmission after a first township hospitalisation were admission year, age, travel time to a county hospital, interval between admissions, first LOS and disease category. If other factors remained constant, patients in the group aged 40–59 years were more likely to be readmitted to a county hospital (OR=1.32). Other factors associated with TC readmission were a shorter travel time to county hospital, shorter LOS, shorter interval between admissions, urinary tract diseases (OR=2.68) or first admission/readmission in a more recent year. The ratio of patients with obstetric or gynaecological diseases readmitted to a county hospital was much lower than that of patients with cancer (OR=0.40).

Table 4.

Multilevel logistic regression model for hospital readmission choice

| Parameter estimate | SE | χ2 | P values | Adjusted OR | |

| Fixed part: | |||||

| Constant | −271.3 | 41.231 | 49.524 | <0.001 | |

| Admitted year* | 0.136 | 0.027 | 47.934 | <0.001 | 1.14 |

| Gender (reference: female) | |||||

| Male | −0.003 | 0.066 | 0.003 | 0.955 | 1.00 |

| Age (reference: less than 20) | |||||

| 20–39 | −0.062 | 0.123 | 0.250 | 0.617 | 0.94 |

| 40–59 | 0.294 | 0.111 | 6.870 | 0.008 | 1.32 |

| More than 59 | 0.034 | 0.102 | 0.116 | 0.735 | 1.03 |

| Travel time (min) | −0.023 | 0.013 | 17.468 | <0.001 | 0.97 |

| Capacity of TH† | −0.017 | 0.035 | 0.204 | 0.658 | 0.98 |

| First LOS (day) | −0.036 | 0.006 | 53.177 | <0.001 | 0.96 |

| First expense (RMB) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.323 | 0.255 | 1.00 |

| Second LOS (day) | −0.002 | 0.003 | 0.213 | 0.644 | 0.99 |

| Interval between admissions (day) | −0.110 | 0.004 | 895.49 | <0.001 | 0.90 |

| Disease category (reference: cancer) | |||||

| ENT | −0.406 | 0.263 | 2.462 | 0.131 | 0.67 |

| Respiratory disease | −0.256 | 0.217 | 1.327 | 0.251 | 0.78 |

| Circulatory disease | 0.512 | 0.256 | 4.627 | 0.028 | 1.64 |

| Digestive disease | 0.553 | 0.227 | 6.217 | 0.013 | 1.74 |

| Urinary disease | 0.982 | 0.264 | 13.950 | <0.001 | 2.68 |

| Haematological disorders | 2.310 | 0.853 | 7.641 | 0.004 | 10.03 |

| Bones and muscles | 0.245 | 0.242 | 1.066 | 0.301 | 1.28 |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | −0.947 | 0.238 | 15.874 | <0.001 | 0.40 |

| Else | −0.132 | 0.265 | 0.251 | 0.617 | 0.88 |

| Random part: | |||||

| Town variance | 0.153 | 0.036 | 17.921 | <0.001 | — |

| Patient scale parameter | 1 | 0.00 | — | — | — |

*TC shows a stable increase in recent years, so admitted year was included in the analysis by order of ranked data.

†Capacity of township hospital included in the analysis by order of ranked data.

ENT, ears, nose and throat; LOS, length of stay; TH-township hospital.

Discussion

Choice for hospital readmission and aggregation

Readmission is common and unavoidable, and can often be attributed to technology and management problems.18 TC readmission accounted for 1.89% of all hospitalisation cases in Qianjiang in 2013, showing steady growth from 2008 (1.66%). In the study period, TC readmission accounted for more than one-third of readmission cases that had a first inpatient admission in a township hospital, which is common in rural China. However, as mentioned, TC readmission (either through doctor referral/recommendation or the patient’s choice) often reflects an inefficient use of health services for patients; TC readmission patients may experience disease delays or cost waste, which may result in patient dissatisfaction regarding the township hospital. A point that needs to be noted here is the uncertainty about whether TT patients had been readmitted to a county hospital three or more times, which has been reported as a real scenario.

The two-level logistic regression analysis showed a hierarchy in the inpatient data (town–patients). Patients’ choice of hospital readmission was clustered at the town level. In other words, 6764 readmitted patients were non-independent, and the choices for hospital readmission in the same town tended to be approximated. The incidence differed in different towns, from 2.95% (Chengnan) to 6.96% (Jindong). The 30 towns in the study area also differed in terms of township hospital, social customs and geographic location. Different township hospitals also have different service concepts and medical capabilities, which might have affected patients’ hospital readmission choice.

Determinants of choice for hospital readmission

Logistic regression analysis showed that patient gender, capacity of township hospital and first admission expenses did not have significant effects on the choice of hospital for readmission. Readmission choice was affected by age, travel time to a county hospital, interval between admissions, LOS in the first admission and disease category. Although the towns in which patients lived affected their choice of hospital for readmission, the capacity of township hospitals had no significant effects; therefore, the town-based effects could be speculatively attributed to social customs and geographic location, which is consistent with a previous study.19 In other words, regardless of capacity of the township hospital, readmission is unavoidable and occurs under the same rate; in theory, TC readmission resulted from the doctors’ assessment of their treatment ability, or deterioration of disease rather than the general hospital capacity.20

In general, patients were more likely to be readmitted to a county hospital if they were in an older age group, found travel to a county hospital more convenient, had lower expenses, had a shorter interval between admissions or diseases that were harder to assess. The ratio of patients choosing to be readmitted to a county hospital increased with age, which may be a result of the increased attention to the cure rate among those of more advanced age. The OR for travel time to a county hospital was 0.97, indicating that patients made their choice based on convenience.16 19 The most obvious influencing factors were first LOS and the interval between admissions. These factors can be combined to discuss the difference in choice. The average first LOS in the TT group was 9.23 days, which is close to 9.7 days, the standard LOS in township hospitals in China.15 Moreover, the average interval between admissions was 14.95 days. In the TC group, the average first LOS was 6.96 days and the interval between admissions was 6.03 days. A shorter first LOS (OR=0.96) and a shorter interval between admissions (OR=0.90) were associated with a greater likelihood of choosing a county hospital. This disparity may be associated with the degree of urgency of the disease. Patients with diseases related to the urinary system (OR=2.68) and haematological disorders (OR=10.03) were more likely to choose a county hospital compared with patients with cancer, respiratory diseases and other disease types. This finding may be related to township doctor assessment regarding treatment ability. Diseases in the urinary and cardiovascular systems and haematological disorders cannot be controlled well in township hospitals, leading to a higher rate of inaccurate assessments and a higher probability of readmission to a county hospital.21 Respiratory and digestive diseases (eg, influenza, paediatric bronchial pneumonia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease22) have a high incidence and recurrence rate and can be controlled in township hospitals. However, these diseases often have failed treatment outcomes because of poor patient compliance on medicine and aftercare.23 Consequently, these patients may be more likely to choose county hospitals for readmission. Moreover, readmissions tended to move toward county hospitals as year increased (OR=1.14), which implies an endogenous factor on the increase of inpatients in county hospitals in recent years.

Identifying forms of TC readmission

We could differentiate TC admission from TT admission by first LOS and interval between admissions. Intervals in TC patient admission showed a U-shaped distribution; 61.1% were readmitted to a county hospital within 3 days, and a small prevalence peak appeared in the group after more than 15 days. Correspondently, 50.1% of patients in the TT group had an interval between admissions of more than 15 days. Therefore, a considerable proportion of early readmissions might be referrals; patients readmitted after a short first LOS with a short interval may be assumed to have been referred by doctors. A long first LOS and long interval were more likely to indicate a TC caused by individual choice, meaning an inappropriate TC readmission. Longer first LOS means a complete treatment in township hospital, and longer interval indicates readmission may have been caused by poor compliance on medicine and aftercare from patients themselves or a normal disease recurrence. Therefore, a combination of first LOS and interval may be an effective identification index; we used 1 week as the cut-off value (table 3). TC readmissions based on a doctor’s incorrect assessment accounted for approximately 70.7% of admissions (interval between admissions <7 days), and those caused by patients accounted for 29.3% (interval between admissions >7 days).

The sample county is a typical rural area, and this research is a population-based study, so the results could present the TC phenomenon in all rural China.

Conclusions

Patients were more likely to choose a county hospital for readmission over time. TC readmission remains a common health service use in rural China, and may result in inappropriate patient flows. Differences in readmission choices were associated with age, travel time to county hospital, first LOS, interval between admissions and diseases; all of these factors are easy to identify. Combination of first LOS and interval between admissions could be an effective identification index for the forms of TC readmission.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Hospitalisation information, geographical factors, interval status and disease were all entered into the logistic regression model. However, some individual factors (eg, economic status, education and preference) were not available. Moreover, influence on choice of hospitals may reflect an accumulated process, meaning that the more patients experience TC readmission, the more significant the influence would become. However, we only studied the influence of the first TC readmission in a single year. These limitations may bring instability to our study and need to be resolved in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: YZ and LZ participated in conception and design and the analyses, and wrote the manuscript. YN participated in data collection and performed the statistical analysis. LZ helped to draft the manuscript, reviewed the manuscript and made final changes. All authors have given their final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This research is supported by the National Youth Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No: 71603088).

Disclaimer: No past publication history, no past presentation history.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The anonymised data set is available through the email of the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Barnett ML, Hsu J, McWilliams JM. Patient characteristics and differences in hospital readmission rates. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1803–12. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sheingold SH, Zuckerman R, Shartzer A. Understanding medicare hospital readmission rates and differing penalties between safety-net and other hospitals. Health Aff 2016;35:124–31. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Orav EJ, et al. Variation in surgical-readmission rates and quality of hospital care. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1134–42. 10.1056/NEJMsa1303118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA 2013;309:372–80. 10.1001/jama.2012.188351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang Y, Zhang L, Tang W, et al. Research on global budget on one certain disease in multilevel institutions: integrated care orientation. Int J Integr Care 2013;13:13S 10.5334/ijic.1277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, et al. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:206–13. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li X, Lu J, Hu S, et al. The primary health-care system in China. Lancet 2017;390:2584–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33109-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Walraven C, Dhalla IA, Bell C, et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ 2010;182:551–7. 10.1503/cmaj.091117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown PH, Theoharides C. Health-seeking behavior and hospital choice in China’s new cooperative medical system. Health Econ 2009;18(Suppl 2):S47–S64. 10.1002/hec.1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Campbell J. Inappropriate admissions: thoughts of patients and referring doctors. J R Soc Med 2001;94:628–31. 10.1177/014107680109401206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang Y, Tang W, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of integrated chronic care models on hypertension outcomes and spending: a multi-town clustered randomized trial in China. BMC Public Health 2017;17 10.1186/s12889-017-4141-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhang Y, Chen Y, Zhang X, et al. Current level and determinants of inappropriate admissions to township hospitals under the new rural cooperative medical system in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:649 10.1186/s12913-014-0649-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang Yan Y. Exploration of the hierarchical integration of rural medical institutions. Chinese Journal of Hospital Administration 2016;8:614–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ye T, Sun X, Tang W, et al. Effect of continuity of care on health-related quality of life in adult patients with hypertension: a cohort study in China. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16 10.1186/s12913-016-1673-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. NHaFPCoC. 2017 China statistics yearbook of health and family planning. Beijing: China union medical university press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Herrin J, St Andre J, Kenward K, et al. Community factors and hospital readmission rates. Health Serv Res 2015;50:20–39. 10.1111/1475-6773.12177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Longford NT. Letter to the editors: improved approximations for multilevel models with binary responses. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 1997;160:593 10.1111/j.1467-985X.1997.00080.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lim SL, Ong KC, Chan YH, et al. Malnutrition and its impact on cost of hospitalization, length of stay, readmission and 3-year mortality. Clin Nutr 2012;31:345–50. 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Calvillo-King L, Arnold D, Eubank KJ, et al. Impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality in pneumonia and heart failure: systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:269–82. 10.1007/s11606-012-2235-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coulourides Kogan A, Koons E, Enguidanos S. Investigating the impact of intervention refusal on hospital readmission. Am J Manag Care 2017;23:E394–E401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ross JS, Chen J, Lin Z, et al. Recent national trends in readmission rates after heart failure hospitalization. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:97–103. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.885210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hartl S, Lopez-Campos JL, Pozo-Rodriguez F, et al. Risk of death and readmission of hospital-admitted COPD exacerbations: European COPD Audit. Eur Respir J 2016;47:113–21. 10.1183/13993003.01391-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vo D, Zurakowski D, Faraoni D. Incidence and predictors of 30-day postoperative readmission in children. Paediatr Anaesth 2018;28:63–70. 10.1111/pan.13290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.