Abstract

Introduction –

Exposure to air pollution is linked to adverse cardiovascular events, even in healthy individuals without underlying disease. Yet, it is clear that the severity of this effect depends on the composition of the air pollution mixture, which can vary quite significantly from one place to another. Therefore, this study was conducted to compare the cardiac effects of particulate matter (PM)-enhanced and ozone(O3)-enhanced smog atmospheres in mice. We hypothesized that O3-enhanced smog would cause greater cardiac dysfunction than PM-enhanced smog due to the higher concentrations of irritant gases.

Methods –

Conscious unrestrained radiotelemetered mice were exposed once whole-body to either PM- (SA-PM) or ozone-enhanced (SA-O3) smog, or filtered air (FA) for four hours. Heart rate (HR) and electrocardiogram (ECG) were recorded continuously before, during and after exposure, and ventilatory function was assessed using a whole-body plethysmograph immediately and 24hrs after exposure.

Results –

Exposure to SA-PM significantly increased HR when compared to both FA and SA-O3. Both smog atmospheres increased heart rate variability (HRV) and neither caused any changes in ventilation after exposure. However, normalization of the responses to PM concentration revealed that SA-O3 was far more potent in increasing HRV and causing ventilatory changes than SA-PM. Furthermore, only SA-O3 caused a significant increase in the number of cardiac arrhythmias. In contrast, there were no differences in any of the parameters between SA-PM and SA-O3 when the responses were normalized to total or gas-phase only hydrocarbons.

Conclusions –

The results of this study demonstrate that even a single exposure to a complex smog mixture causes acute cardiac effects in mice. Although the generalized physiological responses of the PM- and O3-rich smog are similar, the latter is more potent in causing electrical disturbances and breathing changes potentially due to the effects of irritant gases which dominated the mixture. Thus, even though the effects of PM are probably more significant in the long-term, acute cardiac effects appear to be determined by the gases.

Introduction

The association between air pollution exposure and cardiovascular disease is well-established, particularly in people with certain risk factors like high blood pressure or those with pre-existing conditions (Langrish et al. 2012). Unfortunately, the picture is not as clear for healthy individuals and indeed there are still several unknowns with regards to how air pollution mediates cardiovascular dysfunction in this group, especially when there are no observable symptoms. In addition, nationwide variations in air pollution composition make it difficult to determine exactly which components, or combination of components, drive the response. This is the case for complex air pollution mixtures like smog, which originates as a set of primary pollutants (e.g. nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds) that are released from vehicles or industrial sources but thereafter transform after reacting with ultraviolet light to produce secondary pollutants like ozone and certain organic aerosols. Given these uncertainties, research studies need to address the comparative effects of multiple smog atmospheres and focus on determining which compositions, and hence components, cause the most serious health effects.

The American Heart Association cites several pathways by which air pollution, especially particulate matter (PM), leads to decrements in cardiovascular function (Brook et al. 2009, 2010). These include elicitation of oxidative stress and inflammation, alteration of vasomotor properties, translocation of certain pollutants into the systemic circulation and modulation of autonomic controls which regulate the heart and vasculature. Some of these may not manifest as overt symptoms, especially in young healthy individuals, but instead as shifts in normal physiological function which render a person susceptible to subsequent stressors or triggers of adverse responses. We previously showed that exposure to a relatively low concentration of diesel exhaust, which contains many of the same pollutants as smog, caused increased arrhythmias and other cardiovascular effects when healthy rats were challenged with an exercise-like stressor (Hazari et al. 2012; Carll et al. 2013). The insight gained from these and other studies is that exposure to complex air pollution mixtures results in latent autonomic shifts which cause a decrease in cardiac performance during exposure and even up to one day later.

Although many epidemiological studies point to PM as the main cause of air pollution’s impacts on the cardiovascular system (Peters 2005; Pope et al. 2004; Samet et al. 2009), there are numerous human and rodent studies that implicate ubiquitous gaseous irritants like ozone as well (Ruidavets et al. 2005; Farraj et al. 2012; Jerrett et al. 2013). In fact, our previous studies have showed that cardiovascular dysfunction occurs, sometimes at comparable levels or more, even after PM is removed from a multipollutant mixture like diesel exhaust (Hazari et al. 2011; Lamb et al. 2012; Carll et al. 2012). Furthermore, the magnitude of the response is not just determined by the relative levels of PM and ozone but also by the resulting physical and chemical interactions that occur in the mixture. Therefore, the objective of this study was to examine and compare the cardiovascular responses of mice exposed to either a simulated high PM/low ozone (SA-PM) or low PM/high ozone (SA-O3) smog atmosphere. We hypothesized that although both smog mixtures would elicit cardiac changes in mice, the atmosphere dominated by gaseous irritants would be more potent, particularly in causing electrical disturbances like arrhythmia.

Methods

Animals –

Female C57BL/6 (21 ± 1.1 g) mice between 13 and 15 weeks of age were used in this study (Jackson Laboratory - Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were initially housed five per cage and maintained on a 12-hr light/dark cycle at approximately 22°C and 50% relative humidity in an AAALAC–approved facility. Food (Prolab RMH 3000; PMI Nutrition International, St. Louis, MO) and water were provided ad libitum. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and are in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guides for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The animals were treated humanely and with regard for alleviation of suffering. Animals were randomly assigned to one of the following groups after implantation of radiotelemeters: (1) filtered air (FA), (2) SA-PM, or (3) SA-O3.

Surgical Implantation of Radiotelemeters –

Mice were implanted with radiotelemeters as previously described (Kurhanewicz et al. 2014). Animals were anesthetized using inhaled isoflurane (Isothesia, Butler Animal Health Supply, Dublin OH). Anesthesia was induced by spontaneous breathing of 2.5% isoflurane in pure oxygen at a flow rate of 1 L/min and then maintained by 1.5% isoflurane in pure oxygen at a flow rate of 0.5 L/min; all animals received the analgesic buprenorphrine (0.03 mg/kg, i.p. manufacturer). Briefly, using aseptic technique, each animal was implanted subcutaneously with a radiotelemeter (ETA-F10, Data Sciences International, St Paul, MN); the transmitter was placed under the skin to the right of the midline on the dorsal side. The two electrode leads were then tunneled subcutaneously across the lateral dorsal sides; the distal portions were fixed in positions that approximated those of the lead II of a standard electrocardiogram (ECG). Body heat was maintained both during and immediately after the surgery. Animals were given food and water post-surgery and were housed individually. All animals were allowed 7–10 days to recover from the surgery and reestablish circadian rhythms.

Radiotelemetery Data Acquistion –

Radiotelemetry methodology (Data Sciences International, Inc., St. Paul, MN) was used to track changes in cardiovascular function by monitoring heart rate (HR), and ECG waveforms immediately following telemeter implantation, through exposure until 24hours post-exposure. This methodology provided continuous monitoring and collection of physiologic data from individual mice to a remote receiver. Sixty-second ECG segments were recorded every 15 minutes during the pre- and post-exposure periods and every 5 minutes during exposure (baseline and hours 1–4); HR was automatically obtained from the waveforms (Dataquest ART Software, version 3.01, Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN, USA). All animals were acclimated to the exposure chambers on two separate occasions; even then, an increase in HR was always observed when animals were placed in the chamber on the day of exposure.

Electrocardiogram Analysis –

ECGAuto software (EMKA Technologies USA, Falls Church VA) was used to visualize individual ECG waveforms, analyze and quantify ECG segment durations and areas, as well as identify cardiac arrhythmias as previously described (Kurhanewicz et al. 2014). Briefly, using ECGAuto, Pwave, QRS complex, and T-wave were identified for individual ECG waveforms and compiled into a library. Analysis of all experimental ECG waveforms was then based on established libraries. The following parameters were determined for each ECG waveform: PR interval (Pstart-R), QRS complex duration (Qstart-S), ST segment interval (S-Tend) and QT interval (Qstart-Tend). QT interval was corrected for HR using the correction formula for mice QTc = QT/(RR/100)1/2 (Mitchell et al. 1998). Pre-exposure assessments were measured as the exposure time-matched four hours of data from 24 hours before exposure for each animal. Immediately post-exposure assessments were the four hours of data taken immediately post-exposure. Twenty-four post-exposure assessments were the exposure time-matched four hours of data taken 24 hours after exposure.

Heart Rate Variability Analysis –

Heart rate variability (HRV) was calculated as the mean of the differences between sequential RRs for the complete set of ECG waveforms using ECGAuto. For each 1-min stream of ECG waveforms, mean time between successive QRS complex peaks (RR interval), mean HR, and mean HRV-analysis–generated time-domain measures were acquired. The time-domain measures included standard deviation of the time between normal-to-normal beats (SDNN), and root mean squared of successive differences (RMSSD). HRV analysis was also conducted in the frequency domain using a fast-Fourier transform. The spectral power obtained from this transformation represents the total harmonic variability for the frequency range being analyzed. In this study, the spectrum was divided into low-frequency (LF) and high-frequency (HF) regions. The ratio of these two frequency domains (LF/HF) provides an estimate of the relative balance between sympathetic (LF) and vagal (HF) activity.

Whole-Body Plethysmography –

Ventilatory function was assessed in awake, unrestrained mice using a whole-body plethysmograph (Buxco, Wilmington, NC). Assessments were performed one day before exposure, immediately post-exposure and 24hrs after exposure. The plethysmograph pressure was monitored using Biosystems XA software (Buxco Electronics Inc., Wilmington, NC). Using respiratory-induced fluctuations in ambient pressure, ventilatory parameters including tidal volume (VT), breathing frequency (f), inspiratory time (Ti), and expiratory time (Te), were calculated and recorded on a breath-by-breath basis.

Photochemical Smog Exposures –

A gasoline blend was combined with either α-pinene or isoprene to produce a hydrocarbon mixture that was enhanced for particulate matter (PM) or ozone (O3) during irradiation, respectively. Thus, photochemical smog atmospheres with either high PM2.5 and low O3/nitrogen oxide (NOx) concentrations (SA-PM) or low PM2.5 and high O3/NOx (SA-O3) were generated in the Mobile Reaction Chamber (MRC). Briefly, SA-PM was artificially generated with 0.491 ppm nitrogen oxide (NO), 0.528 ppm NOx, 29.9 ppmC total hydrocarbons (THC), 24 ppmC gasoline and 5.3 ppmC α -pinene as the initial conditions, whereas SA-O3 was generated from 0.794 ppm NO, 0.912 ppm NOx, 12.4 ppmC THC, 5.2 ppmC isoprene and 7.21 ppmC gasoline. Each of the initial smog mixtures was then irradiated with ultraviolet light. Smog was then transported under vacuum to 0.3 m3 whole body inhalation chambers where mice were exposed once for four hours. Continuous gas and aerosol sampling for carbon monoxide (CO), O3, NOx, THC and particle mass concentration were conducted at both the MRC unit as well as from the inhalation exposure systems. All PM was formed as secondary organic aerosol (SOA) from the photochemical reactions in the MRC. Particle size distributions and gravimetric mass sampling was measured, and filter sampling for gravimetric analysis were conducted for the entire exposure time. Volatile organic compound (VOC) summa cannisters were periodically collected and analyzed by gas chromatography off-line to determine concentrations of various volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the exposure atmosphere. Please refer to Krug et al. in this issue for complete exposure details.

Statistics –

All data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using Sigmaplot 13.0 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA) software. The delta values (i.e. change during exposure from baseline) of HR, HRV and the ventilatory parameters were used and a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated-measures was employed with Bonferroni post hoc tests to determine statistical differences. Raw ECG and arrhythmia count data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. HR, HRV, ventilatory parameters and arrhythmia counts were also normalized to total hydrocarbons (both particle and gas phases), gas-phase hydrocarbons only or PM concentration to compare the relative contribution of these components to the physiological response to Smog A versus B and their relative potencies. The statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Exposure characteristics –

Table 1 shows the inhalation chamber concentrations of PM2.5 (i.e. secondary organic aerosols), NOx, O3, as well as total hydrocarbons in the complete smog mixture (particle and gas phases) and in the gas-phase only for both SA-PM (enhance PM2.5) and SA-O3 (enhanced O3). In addition, the respective Air Quality Health Indexes (AQHI) and Air Quality Indexes (AQI) along with their color codes are also included to provide a health-risk comparison between these atmospheres. Refer to Krug et al. in this issue for a more comprehensive comparison of SA-PM (MR044) and SA-O3 (MR059).

TABLE 1.

| PM2.5 (mg/m3) AQI |

NOx/AQI (ppm) AQI |

O3/AQI (ppm) AQI |

Total hydrocarbons (ppmc) |

Gas-phase (mgC/m3) |

AQHI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA-PM | 1.0362 >500 (brown) |

0.380 130 (orange) |

0.190 71.8 (yellow) |

5.5 | 3.847 | 92.5 |

| SA-O3 | 0.0523 305 (brown) |

0.647 194 (red) |

0.448 286 (purple) |

6.1 | 3.125 | 102.6 |

Heart rate –

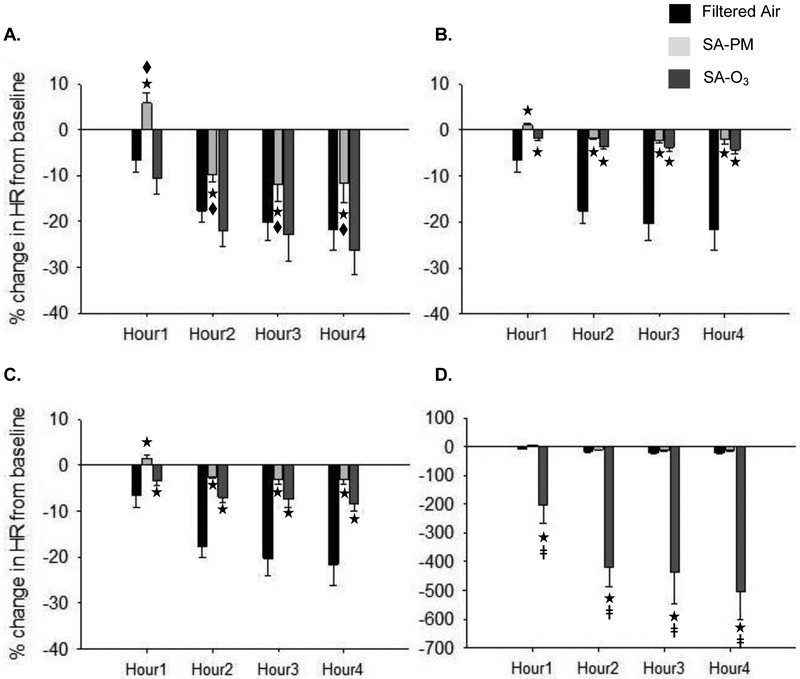

There was no difference in the baseline HR, which was the resting level measured in the home cages, between any of the groups (FA = 588.0 ± 19.8 bpm; SA-PM = 568.6 ± 7.5 bpm; SA-O3 = 565.9 ± 9.4 bpm). In general, all animals experienced a decrease in HR during the exposure; although, SA-PM caused a significant increase in HR during Hour1 and less HR decrease over the remaining exposure period when compared to FA and SA-O3 (Fig. 1A). However, there was no difference between SA-PM and SA-O3 when the responses were normalized to THC (Fig. 1B) or gas-phase hydrocarbons only (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, HR decrease was significantly greater during SA-O3 when compared to SA-PM after normalization to PM concentration (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Exposure to smog alters heart rate responses in mice. In general, mice experienced a steady decrease in HR (from baseline) over the first two hours of exposure, which then leveled off in hours three and four. Mice exposed to SA-PM experienced a significant increase in HR during the first hour and had less decrease in HR thereafter when compared to FA and SA-O3 (A.). However, there was no difference between SA-PM and SA-O3 when the change in HR during exposure was normalized to total hydrocarbons (B.) or gas-phase hydrocarbons only (C.). In contrast, decrease in HR during SA-O3 exposure was significantly greater than SA-PM when responses were normalized to PM concentration (D.). ★significantly different from FA; ◆ significantly different from SA-O3; ǂ significantly different from SA-PM. p < 0.05.

Arrhythmia –

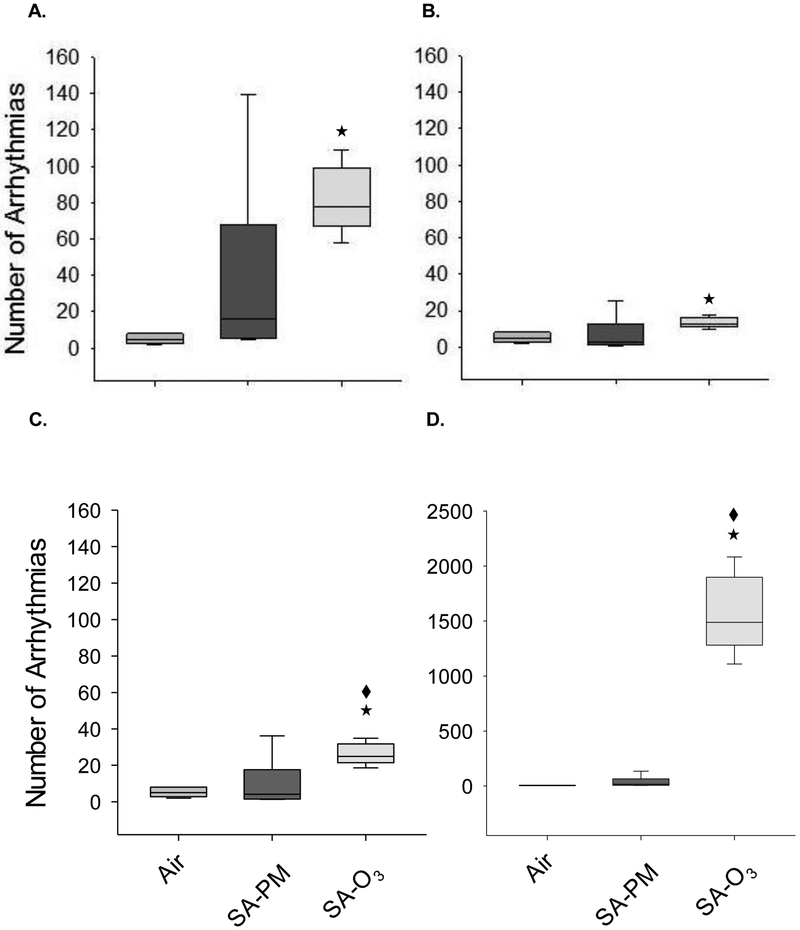

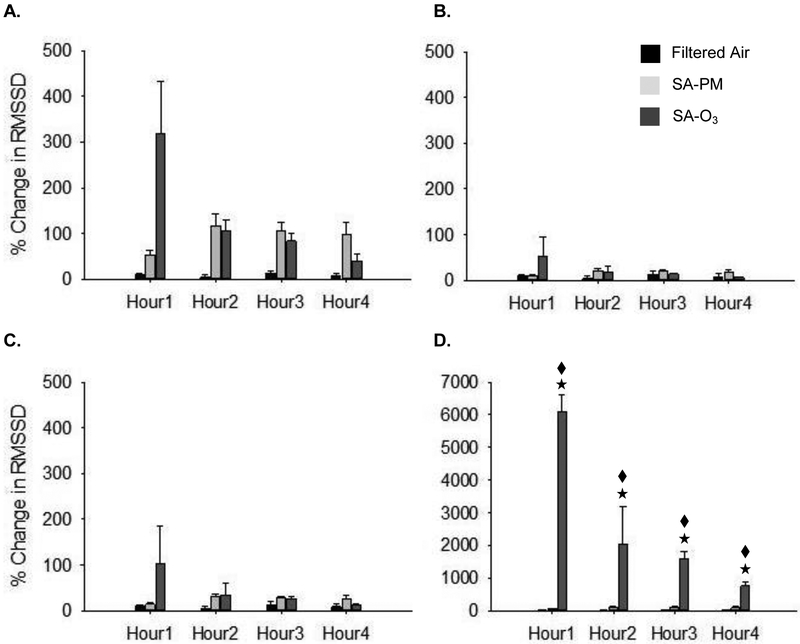

None of the animals experienced cardiac arrhythmias during the pre-exposure period. Figure 2 shows the raw arrhythmia counts during the four-hour exposure. Overall, exposure to SA-O3 increased the incidence of arrhythmias when compared to FA (Fig. 2A-D) but there was no difference with respect to SA-PM in the denormalized (Fig. 2A) and THC normalized (Fig. 2B) responses. In contrast, SA-O3 caused significantly more arrhythmias than SA-PM when the responses were normalized to gas-phase hydrocarbons (Fig. 2C) or PM concentrations (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Exposure to O3-enhanced smog increases cardiac arrhythmias in mice. Overall, exposure to SA-O3 caused a significant increase in the number of cardiac arrhythmias in mice when compared to FA. There was no difference between SA-O3 and SA-PM in the denormalized (A.) and THC-normalized (B.) responses; however, SA-O3 caused significantly more arrhythmias than SA-PM when the responses were normalized to gas-phase hydrocarbons (C.) or PM concentration (D.). ★significantly different from FA; ◆ significantly different from SA-PM. p < 0.05.

Heart rate variability –

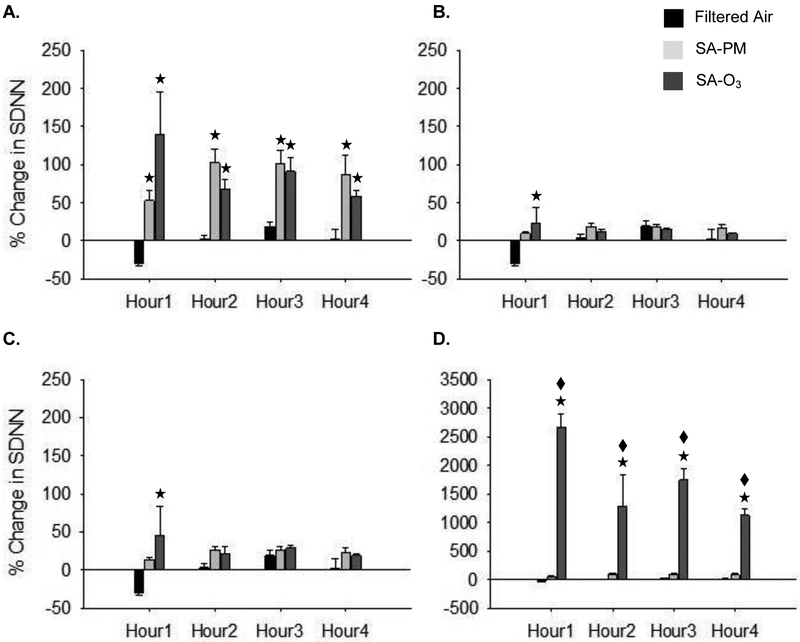

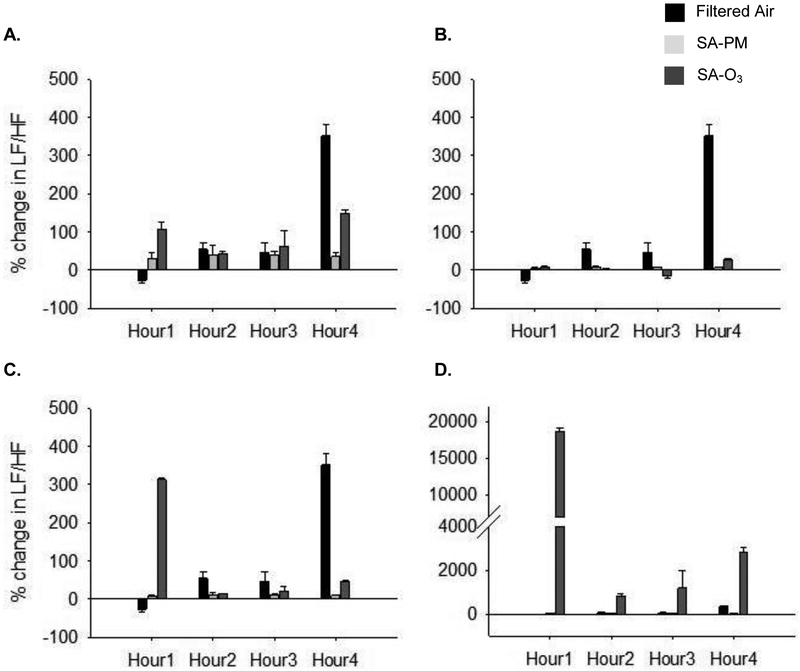

Figures 3–5 show the changes in HRV during exposure. There were no significant differences in the baseline HRV measures between any of the groups (FA – SDNN = 7.4 ± 0.7 msec, RMSSD = 4.0 ± 0.5 msec, LF/HF = 8.4 ± 0.7 msec2; SA-PM – SDNN = 7.9 ± 0.7 mscec, RMSSD = 5.3 ± 0.6 msec, LF/HF = 7.1 ± 0.6 msec2; SA-O3 – SDNN = 8.7 ± 0.7 msec, RMSSD = 5.5 ± 0.7 msec, LF/HF = 6.7 ± 0.6 msec2). SDNN decreased in the first hour of exposure in control animals; this was likely due to sympathetic modulation from the stress of handling and placement in the chamber. Animals exposed to either SA-PM or SA-O3 had a significant increase in SDNN (Fig. 3A) when compared to FA and a similar trend was observed for RMSSD (Fig. 4A). Both time-domain measures showed minimal to no effects for either SA-PM or SA-O3 when the responses were normalized to THC (Fig. 3B and 4B) or gas-phase hydrocarbons only (Fig. 3C and 4C). However, the increase in SDNN and RMSSD during SA-O3 exposure was significantly greater than SA-PM when the data were normalized to PM concentration (Fig. 3D and 4D). On the other hand, there were no significant effects in the frequency-domain measures (i.e. LF/HF) for either smog atmosphere with or without normalization of responses (Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

Exposure to smog increases SDNN in mice. SDNN decreased during the first hour of FA exposure probably due to stress. On the other hand, mice exposed to either SA-PM or SA-O3 experienced a significant increase in SDNN (A.) when compared to FA. There was no difference in SDNN between SA-PM and SA-O3 in the denormalized (A.), THC- (B.) or gas-phase only hydrocarbon (C.) normalized responses. In contrast, SDNN was significantly increased during SA-O3 exposure when compared to SA-PM when responses were normalized to PM concentration (D.). ★significantly different from FA; ◆ significantly different from SA-PM. p < 0.05.

Figure 5.

Change in LF/HF during smog exposure. There were no significant effects of SA-PM or SA-O3 on LF/HF when compared to FA or when either smog atmosphere was compared to the other (A.). Normalization of the responses to THC- (B.), gas-phase only hydrocarbons (C.), or PM concentrations (D.) did not reveal any significant difference between SA-PM and SA-O3 except in (D.) where a trend of increase was observed in SA-O3-exposed mice.

Figure 4.

Exposure to O3-enhanced smog increases RMSSD in mice. There was no effect of SA-PM or SA-O3 on RMSSD when compared to FA although a trend of increase was observed for both (A.). There was no difference in RMSSD between SA-PM and SA-O3 in the THC- (B.) or gas-phase only hydrocarbon (C.) normalized responses. On the other hand, RMSSD was significantly increased during SA-O3 exposure when compared to SA-PM when responses were normalized to PM concentration (D.). ★significantly different from FA; ◆ significantly different from SA-PM. p < 0.05.

Ventilatory function –

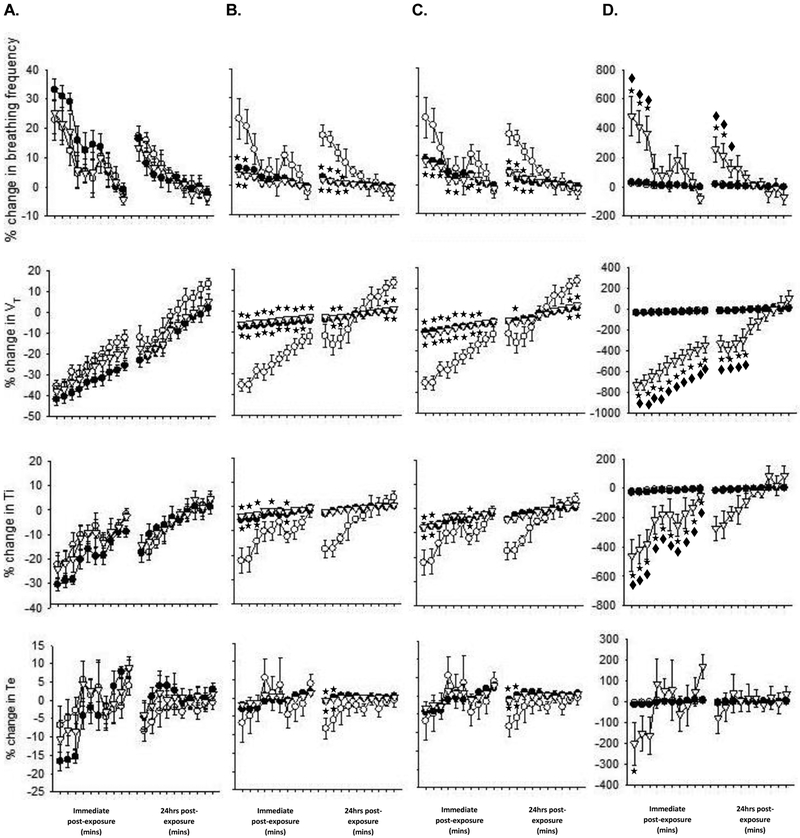

Whole-body plethysmography was performed on all animals during the baseline period as well as immediately and one day after exposure; results shown in Fig. 6 compare the changes in ventilatory parameters from baseline between the groups. Baseline values did not differ between the groups (FA – f = 475.1 ± 13.1 breaths/min, VT = 0.24 ± 0.01 ml, Ti = 0.06 ± 0.002 sec, Te = 0.08 ± 0.002 sec; SA-PM – f = 509.8 ± 6.3 breaths/min, VT = 0.24 ± 0.01 ml, Ti = 0.05 ± 0.001 sec, Te = 0.07 ± 0.001 sec; SA-O3 – f = 499.7 ± 12.1 breaths/min, VT = 0.25 ± 0.01 ml, Ti = 0.06 ± 0.002 sec, Te = 0.07 ± 0.002 sec). There were no differences in f, VT, Ti or Te between any of the groups in the denormalized results (Fig. 6A). However, normalizing to THC (Fig. 6B) or gas-phase only hydrocarbons (Fig. 6C) revealed a significant decrease in f, and increase in VT and Ti in SA-PM and SA-O3 immediately after exposure when compared to controls. Some of these responses relative to FA persisted one day after exposure but there was no difference between SA-PM and SA-O3. In stark contrast, normalization to PM concentrations revealed a significant increase in f, and decrease in VT and Ti immediately after exposure in SA-O3-exposed animals when compared to SA-PM (Fig. 6D); only the changes in f and VT persisted 24hrs later.

Figure 6.

O3-enhanced smog alters breathing in mice immediately after exposure. There was no effect of SA-PM (filled circles) or SA-O3 (open triangles) on any ventilatory parameters when compared to FA (open circles) (A.) and there were no differences observed between SA-PM and SA-O3 in the THC- (B.) or gas-phase only hydrocarbon (C.) normalized responses. However, f was increased, and VT and Ti were significantly decreased after SA-O3 exposure when compared to SA-PM when responses were normalized to PM concentration (D.). ★significantly different from FA; ◆ significantly different from SA-PM. p < 0.05.

Electrocardiogram –

There were no baseline differences in any ECG parameters between any of the groups. Changes in ECG during exposure were restricted to a PR interval prolongation in mice exposed to SA-PM, which were significantly higher than FA and SA-O3 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

| PR interval (msec) |

QRS duration (msec) |

QTc (msec) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Air |

|||

| Baseline | 36.1 ± 0.5 | 14.7 ± 1.9 | 94.2 ± 3.0 |

| Hour 1 | 33.4 ± 1.8 | 13.9 ± 0.5 | 92.7 ± 1.5 |

| Hour 2 | 35.7 ± 1.4 | 14.6 ± 0.4 | 92.9 ± 1.5 |

| Hour 3 | 35.9 ± 0.6 | 14.8 ± 0.4 | 94.9 ± 3.0 |

| Hour 4 | 37.5 ± 1.0 | 15.3 ± 0.4 | 94.5 ± 2.0 |

| 24hrs Post-exp | 36.0 ± 0.7 | 16.3 ± 0.3 | 94.6 ± 4.0 |

| SA-PM |

|||

| Baseline | 32.8 ± 0.6 | 14.6 ± 0.3 | 88.2 ± 1.5 |

| Hour 1 | 40.7 ± 1.0*◆ | 13.3 ± 0.2 | 91.0 ± 4.6 |

| Hour 2 | 42.3 ± 1.1*◆ | 13.4 ± 0.4 | 93.3 ± 4.1 |

| Hour 3 | 43.3 ± 0.9*◆ | 13.7 ± 0.2 | 91.7 ± 2.6 |

| Hour 4 | 42.8 ± 1.2*◆ | 13.6 ± 0.3 | 99.3 ± 7.0 |

| 24hrs Post-exp | 33.4 ± 0.5 | 14.4 ± 0.2 | 81.5 ± 1.4 |

| SA-O3 |

|||

| Baseline | 33.6 ± 0.9 | 13.4 ± 1.1 | 89.9 ± 1.8 |

| Hour 1 | 34.4 ± 1.1 | 11.8 ± 2.2 | 95.9 ± 3.4 |

| Hour 2 | 36.3 ± 0.8 | 11.0 ± 2.4 | 91.5 ± 3.6 |

| Hour 3 | 36.6 ± 0.7 | 9.6 ± 3.2 | 92.7 ± 4.9 |

| Hour 4 | 37.1 ± 0.7 | 10.1 ± 2.8 | 92.4 ± 2.9 |

| 24hrs Post-exp | 34.2 ± 0.6 | 14.4 ± 0.8 | 88.9 ± 0.8 |

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that a single inhalation exposure to atmospheric smog causes acute cardiovascular dysfunction in mice, irrespective of whether it is comprised predominantly of PM or O3. Yet, our findings also suggest that multipollutant mixtures which have a higher irritant gas composition are likely to cause more potent acute cardiac effects than those with higher PM/lower gases. In an effort to properly compare SA-PM and SA-O3, we normalized the data from this study to total hydrocarbons, gas-phase hydrocarbons only and PM concentration. Normalization of the results showed that there was no difference in heart rate, heart rate variability or cardiac arrhythmias between SA-PM, or PM-enhanced smog, and SA-O3, or O3-enhanced smog, when differences in total hydrocarbons or gas-phase only hydrocarbons were taken into account. In contrast, SA-O3 caused significantly greater cardiac effects than SA-PM when results were normalized to PM concentration indicating that the difference in response was mediated by the gaseous components. Thus, these novel findings point to the complexity of interactions between air pollution components and the reactions that determine the composition of the final mixture and the resulting cardiovascular response.

Real-time cardiovascular measurements and responses to exposure as derived here from radiotelemetry often include stress-related effects (e.g. from handling, noise, etc). This was observed in all animals as a transient increase in heart rate upon placement in the exposure chamber, which occurred despite several acclimatizations. In controls, the overall heart rate progressively decreased per hour of exposure as the animals calmed down in the chambers. Similar responses were observed with SA-O3 but with a trend of greater decrease in heart rate. Although this result was not statistically significant, it is not entirely surprising that SA-O3 would have this effect given it was rich in irritant gases like O3, NOx and reactive aldehydes, which have the ability to activate airway sensory nerves, elicit autonomic reflexes and modulate parasympathetic function (Widdicombe and Lee 2001; Taylor-Clark and Undem 2006; Kurhanewicz et al. 2016). On the other hand, SA-PM caused a significant increase in heart rate in the first hour of exposure and less decrease (i.e. HR remained elevated above normal) over the remaining exposure period when compared to controls and SA-O3. These disparate effects of SA-PM and SA-O3 are not unusual. We previously showed that exposure to particle-filtered diesel exhaust caused greater decrements in heart rate than whole diesel exhaust (Lamb et al. 2012) while particle-rich air pollution has been shown to increase heart rate (Peters et al. 1999; Unosson et al. 2013). Thus, it appears from our data that decreases in heart rate during such exposures are due to the relative content and concentration of gases in the complex air pollution mixture. Notice that normalization of the heart rate to total or gas-phase only hydrocarbons did not reveal any difference between SA-PM and SA-O3, yet when the “effects” of PM were eliminated through normalization O3-enhanced SA-O3 caused a significant decrease in heart rate when compared to SA-PM.

Admittedly, the composition of the smog atmospheres may not have been the only determinant of this response, variations in the smell of SA-PM and SA-O3 could have contributed as well. SA-PM had a very potent smell when compared to SA-O3 and this may have caused an increase in the heart rate. This effect has been demonstrated previously, particularly with burnt or unpleasant smells (Glass et al. 2014), and appears to be mediated by an increase in sympathetic modulation or decrease in heart rate variability. Yet, it is likely that in addition to smell, several smog factors could have triggered responses and altered autonomic function simultaneously, particularly given the complexity of the atmosphere (e.g. potent “burnt” smell + chemical airway irritation + secondary activation due to inflammation). In any case, the autonomic nervous system controls the heart and vasculature through a dynamic ebb and flow of both parasympathetic and sympathetic influence and tends to lean in the direction of one or the other based on the physiological circumstances. Thus, returning to the issue of composition, the difference in response between a predominantly gaseous mixture and one that is high in particulates would depend on the sum of all the factors that impact autonomic function, and hence the resulting direction would be determined by which factor(s) dominates.

Although our data does not necessarily demonstrate this (i.e. parasympathetic/sympathetic activation) directly, it is possible that irritant gases drove a predominantly parasympathetic response whereas the PM-rich mixture caused a stress-induced sympathetic modulation. We observed a greater increase in SDNN and RMSSD, which is indicative of parasympathetic modulation, during SA-O3 exposure when compared to SA-PM. This response was due to the effects of the gas-phase components given the difference in these parameters between the two smog atmospheres became evident when we normalized to PM concentration. As far as PM is concerned, studies have demonstrated, as stated previously, that it not only increases heart rate, blood pressure, low frequency blood pressure variability and noradrenalin release (i.e. stress), but also causes a decrease in heart rate variability (Brook et al. 2010; Ying et al. 2014). All of these changes point to sympathetic modulation and a perceived increase in cardiac risk. However, we observed an increase in SDNN and RMSSD even with the PM-enhanced SA-PM mixture. This might be explained by the fact that SA-PM also contained irritant gases, some of which were present in high concentrations (see Krug et al. in this issue) and could have opposed the sympathetic modulatory effect of the PM. A lack of response in the LF/HF ratio suggests this parasympathetic-sympathetic push and pull (Billman 2013).

Comparisons between SA-PM and SA-O3 also included the air quality health index or AQHI, which indicates the health risk of both atmospheres. The equation for this index provides the relative contribution of the PM2.5 and the oxidant gases towards the health metric. In the case of SA-O3, oxidant gases contributed to 97% of the AQHI with a negligible amount coming from PM, once again pointing to the fact that it’s effects were predominantly mediated by irritant gases. In contrast, PM contributed to almost 70% of the AQHI of SA-PM, yet it also had a fairly significant contribution (30%) from the oxidant gases as well (see Krug et al. this issue). These results seem to confirm our conclusions that although the effects of SA-O3, which included a significant decrease in heart rate and increase in heart rate variability, were almost entirely driven by gases, SA-PM’s effects were likely driven by both.

While an increasing or decreasing heart rate or heart rate variability during exposure merely indicates a physiological change, one could potentially infer cardiac dysfunction when it is a deviation from the control response. Yet even then it represents fluctuations that can normally happen in mammals (e.g. exercise or physical exertion). Sometimes these responses reflect adverse cardiac issues more strongly when observed in conjunction with cardinal signs of dysfunction like arrhythmia. This may be the case for what we observed in the mice exposed to these smog atmospheres. We have repeatedly shown that gaseous air pollution is more arrhythmogenic than one with a high concentration of PM (Hazari et al. 2009, 2011, 2014) and the same appears to be the case in this study. SA-O3, particularly when normalized to PM concentration, caused a significantly greater number of sinoatrial (SA) node dysfunction than SA-PM. Furthermore, we found that SA-O3 was more arrhythmogenic than SA-PM even when normalized to gas-phase hydrocarbons suggesting PM had very little effect. This form of arrhythmia or dysrhythmia is due to an abnormal delay in the firing of the SA node and manifests as blocked p-waves and alternating runs of bradycardia followed by tachycardia; this can increase the risk of escape beats and cardiac insufficiency in humans. Interestingly, some of the causes behind this phenomenon include an increase in vagal tone and airway irritation which leads to dyspneic breathing and airway spasm, both of which were observed in our animals (Benditt et al. 2007; Haqqani and Kalman 2007).

Exposure to SA-PM did cause a prolongation of the PR interval, which in some cases is normal but also can indicate a cardiac conduction abnormality. However, in the absence of other effects (e.g. arrhythmia) it would be hard to say that there was any real dysfunction in these mice. Indeed, even changes in breathing impact the heart on a breath-by-breath basis and through this physiological coupling the heart is able to maintain proper function (Ben-Tal et al. 2012). Thus, alterations in breathing due to airway irritation and airflow obstruction have the potential to cause adverse cardiac events. Yet, we did not observe any remarkable differences in ventilatory parameters either immediately following the exposure or one day later for either SA-PM or SA-O3. Normalization to total or only gas-phase hydrocarbons did not reveal any differences but SA-O3 caused a significant increase in breathing frequency, and decreases in tidal volume and inspiratory time when the results were normalized to PM concentration. Thus, once again it appears that the gases in SA-O3 caused a rapid shallow breathing in mice possibly due to irritation.

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrate that inhalation exposure to a complex smog atmosphere causes acute cardiac effects in mice, and that the composition of the pollution mixture likely plays a key role in determining the degree of responsiveness. Although there’s no question that the PM-enhanced smog caused a change in cardiac function, it is likely that a single exposure was not enough to elicit worsening symptoms in our relatively young healthy animals. This is particularly true for the relatively low number of cardiac arrhythmias observed in those animals. It is entirely likely however that repeated exposures would have had a more pronounced impact. In contrast, the O3-enhanced smog caused a set of physiological changes which if considered with the increased incidence of arrhythmia suggest an acute irritant gas-mediated autonomic modulation and electrical disturbance. Even though the former is not considered a “toxicological” response, it does reflect a change from the homeostatic normal state of the body. These short-lived reversible effects probably do not pose a serious hazard to the body on their own, but when combined with an additional stressor could predispose the heart to dysfunction, particularly during in the 24 hours following exposure.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: This paper has been reviewed and approved for release by the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the U.S. EPA, nor does mention of trade names.

References

- Ben-Tal A, Shamailov SS and Paton JFR (2012). Evaluating the physiological significance of respiratory sinus arrhythmia: looking beyond ventilation–perfusion efficiency. J. Physiol 590:1980–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benditt DG, Sakaguchi S, Lurie KG and Lu F (2007). Sinus node dysfunction In Cardiovascular Medicine, Eds. Willerson James T., Wellens Hein J. J., Cohn Jay N., Holmes David R. Jr. Springer, London. [Google Scholar]

- Billman GE (2013). The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Front. Physiol 4: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Urch B, Dvonch JT, Bard RL, Speck M, Keeler G, Morishita M, Marsik FJ, Kamal AS, Kaciroti N, Harkema J, Corey P, Silverman F, Gold DR, Wellenius G, Mittleman MA, Rajagopalan S and Brook JR (2009). Insights into the mechanisms and mediators of the effects of air pollution exposure on blood pressure and vascular function in healthy humans. Hypertension 54(3):659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, Holguin F, Hong Y, Luepker RV, Mittleman MA, Peters A, Siscovick D, Smith SC Jr, Whitsel L and Kaufman JD (2010). Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 121(21), 2331–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carll AP, Hazari MS, Perez CM, QT Krantz, King CJ, DW Winsett, Costa DL and Farraj AK (2012). Whole and particle-free diesel exhausts differentially affect cardiac electrophysiology, blood pressure, and autonomic balance in heart failure-prone rats. Toxicol. Sci 128(2):490–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carll AP, Hazari MS, Perez CM, Krantz QT, CJ King, Haykal-Coates N, Cascio WE, Costa DLand Farraj AK (2013). An autonomic link between inhaled diesel exhaust and impaired cardiac performance: insight from treadmill and dobutamine challenges in heart failure-prone rats. Toxicol. Sci;135(2):425–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farraj AK, Hazari MS, Winsett DW, Kulukulualani A, Carll AP, Haykal-Coates N, Lamb CM, Lappi E, Terrell D, Cascio WE and Costa DL (2012). Overt and latent cardiac effects of ozone inhalation in rats: evidence for autonomic modulation and increased myocardial vulnerability. Environ. Health Perspect 120(3):348–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass ST, Lingg E and Heuberger E (2014). Do ambient urban odors evoke basic emotions? Front. Psychol 5: 340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haqqani HM and Kalman JM (2007). Aging and sinoatrial dysfunction. Circulation 115:1178–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazari MS, Callaway J, Winsett DW, Lamb C, Haykal-Coates N, Krantz QT, King C, Costa DL and Farraj AK (2012). Dobutamine ”stress” test and latent cardiac susceptibility to inhaled diesel exhaust in normal and hypertensive rats. Environ. Health Perspect ;120(8):1088–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazari MS, Haykal-Coates N, Winsett DW, Krantz QT, King C, Costa DL and Farraj AK (2012). TRPA1 and sympathetic activation contribute to increased risk of triggered cardiac arrhythmias in hypertensive rats exposed to diesel exhaust. Environ. Health Perspect 119(7):951–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerrett M, Burnett RT, Beckerman BS, Turner MC, Krewski D, Thurston G, Martin RV, van Donkelaar A, Hughes E, Shi Y, Gapstur SM, Thun M and Pope CA (2013). Spatial Analysis of Air Pollution and Mortality in California. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 188(5):593–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurhanewicz N, McIntosh-Kastrinsky R, Tong H, Walsh L, Farraj AK and Hazari MS (2014). Ozone co-exposure modifies cardiac responses to fine and ultrafine ambient particulate matter in mice: concordance of electrocardiogram and mechanical responses. Part. Fibre Toxicol October 16;11:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurhanewicz N, McIntosh-Kastrinsky R, Tong H, Ledbetter A, Walsh L, Farraj A and Hazari M (2016). TRPA1 mediates changes in heart rate variability and cardiac mechanical function in mice exposed to acrolein. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 324:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb CM, Hazari MS, Haykal-Coates N, Carll AP, Krantz QT, King C, Winsett DW, Cascio WE, Costa DL and Farraj AK (2012). Divergent electrocardiographic responses to whole and particle-free diesel exhaust inhalation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Toxicol. Sci 125(2):558–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langrish JP, Bosson J, Unosson J, Muala A, Newby DE, Mills NL, Blomberg A and Sandström T (2012). Cardiovascular effects of particulate air pollution exposure: time course and underlying mechanisms. J Intern. Med 272(3):224–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GF, Jeron A and Koren G (1998). Measurement of heart rate and Q-T interval in the conscious mouse. Am. J Physiol 274(3) Pt 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A, Perz S, Dfiring A, Stieber J, Koenig W, and Wichmann HE (1999). Increases in Heart Rate during an Air Pollution Episode. Am. J. Epidemiol 150:1094–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A (2005). Particulate matter and heart disease: evidence from epidemiological studies. Toxicol. App. Pharmacol 207(2 Suppl):477–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA 3rd, Burnett RT, Thurston GD, Thun MJ, Calle EE, Krewski D and Godleski JJ (2004). Cardiovascular mortality and long-term exposure to particulate air pollution: epidemiological evidence of general pathophysiological pathways of disease. Circulation 109(1):71–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruidavets JB, Cournot M, Cassadou S, Giroux M, Meybeck M and Ferrières J. (2005). Ozone air pollution is associated with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 111(5):563–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JM, Rappold A, Graff D, Cascio WE, Berntsen JH, Huang Y-C T, Herbst M, Bassett M, Montilla T, Hazucha MJ, Bromberg PA and Devlin RB (2009). Concentrated ambient ultrafine particle exposure induces cardiac changes in young healthy volunteers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 179(11):1034–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Clark TE and Undem BJ (2006). Ozone activates airway nerves via the selective stimulation of TRPA1 ion channels. J. Physiol 588:423–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unosson J, Blomberg A, Sandström T, Muala A, Boman C, Nyström R, Westerholm R, Mills NL, Newby DE, Langrish JP and Bosson JA (2013). Exposure to wood smoke increases arterial stiffness and decreases heart rate variability in humans. Part. Fibre Toxicol 6;10:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdicombe J and Lee LY (2001). Airway reflexes, autonomic function, and cardiovascular responses. Environ. Health Perspect 109:579–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Z, Xu X, Bai Y, Zhong J, Chen M, Liang Y, Zhao J, Liu D, Morishita M, Sun Q, Spino C, Brook RD, Harkema JR and Rajagopalan S (2014). Long-term exposure to concentrated ambient PM2.5 increases mouse blood pressure through abnormal activation of the sympathetic nervous system: a role for hypothalamic inflammation. Environ. Health Perspect 122(1):79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]