Abstract

Although women diagnosed with cancer during their childbearing years are at significant risk for infertility, we know little about the relationship between infertility and long-term quality of life (QOL). To examine these relationships, we assessed psychosocial and reproductive concerns and QOL in 231 female cancer survivors. Greater reproductive concerns were significantly associated with lower QOL on numerous dimensions (P<.001). In a multiple regression model, social support, gynecologic problems, and reproductive concerns accounted for 63% of the variance in QOL scores. Women who reported wanting to conceive after cancer, but were not able to, reported significantly more reproductive concerns than those who were able to reproduce after cancer (P<.001). These preliminary data suggest that at least for vulnerable subgroups, the issue of reproductive concerns is worthy of additional investigation to assist cancer survivors living with the threat or reality of infertility.

Background

Women diagnosed with cancer during their childbearing years are often treated with surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy. Reproductive and sexual organs are frequently either directly or indirectly involved in cancer treatment, thereby having the potential to negatively affect psychosocial and sexual functioning, as well as fertility (1). Despite this, few empirical investigations have addressed the co-occurring reproductive and quality of life concerns which might result from a cancer diagnosis during childbearing years (2). Prior cancer survivorship research illustrates the complexity of this association, and the premise that despite good quality of life years after the initial cancer treatment, women diagnosed with cancer during childbearing age can experience persistent sexual problems, fertility concerns, and adverse psychosocial sequelae (1, 3–7). To date, however, the relationship between infertility and overall quality of life into long-term cancer survivorship is unknown.

To examine these important relationships, we assessed key concepts related to reproductive concerns in female cancer survivors including gynecologic symptoms, quality of life, and emotional and physical well-being. Our purpose was to describe a range of reproductive concerns experienced by long-term female cancer survivors, and determine whether the issue of reproductive concerns among this group of long-term cancer survivors can be measured.

Methods

Study Design and Recruitment

This analysis was conducted using data from a study examining quality of life (QOL) concerns and specific psychosocial sequelae associated with long-term survivorship among women diagnosed with a gynecologic malignancy or lymphoma during childbearing age. In this study, women were eligible if they had been diagnosed and treated 5–10 years earlier. Women with recurrent disease or second malignancy, or those with a psychiatric or cognitive disorder that precluded informed consent, were not eligible. This cross-sectional study included 231 women diagnosed with cervical cancer, gestational trophoblastic tumors (GTT), or lymphoma (Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin) with a diagnosis occurring between the ages of 17 and 45, and 148 controls.

Subsequent to IRB approval at all institutions, eligible patients received a letter of invitation describing the study along with a return postcard indicating participation or refusal to complete a survey. Women who agreed to participate in the study received a copy of the informed consent and the survey. Upon receiving the signed informed consent, participants elected to complete either the telephone or postal survey. The participants were asked to provide the contact information (e.g., name, phone number) of three female acquaintances who were within 5 years of the participant’s age, from the same ethnic/racial background, and without a history of cancer. This recruitment procedure was utilized to contact control participants.

General QOL results from this study have been presented elsewhere (3, 4). Briefly, these results suggest that although women report excellent QOL overall, they also recognize life domains that may have been negatively affected by the cancer experience (e.g., sexual functioning). This paper focuses on as yet unpublished results examining reproductive concerns and their relationship to QOL among female cancer survivors.

Participants

Survivors

Cervical cancer survivors

Cervical cancer survivors were identified from two Cancer Registry Programs: (a) The Cancer Surveillance Program of Orange County (CSPOC) at University of California, Irvine (UCI) (N = 21) and (b) The Colorado Central Cancer Registry (CCCR) (N = 30). Based on total cases considered eligible and reachable, this sample size represented an average participation rate of 88%. The majority of the registry cases initially identified as eligible were unable to be located (approximately 67%).

Lymphoma survivors

Lymphoma survivors were identified from three sources: (a) CSPOC at UCI (N = 10), (b) CCCR (N = 36), and (c) the Weston Park Hospital Sheffield in the UK (N = 23). This sample size represented an average participation rate of 91% among registry cases, and over 95% participation among the clinic-based cases. Similar to the cervical cancer registry cases, approximately 51% of registry cases initially identified as study eligible were unable to be located.

GTT survivors

GTT survivors were enrolled through the Dana Farber Cancer Institute/Brigham Women’s Hospital of the New England Trophoblastic Disease Center (NETDC) (N = 48) in the U.S. as well as two trophoblastic centers in the U.K. (Weston Park Hospital, Sheffield and Charing Cross Hospital, London) (N = 63). This sample size represented an average participation rate of 95%, based on total cases considered eligible and reachable.

Controls

In this unmatched design, a total of 148 acquaintance controls were generated from 15 cervical cancer, 111 GTT and 21 lymphoma study participants.

Measures

Participants completed a 60-minute phone or mail survey that included demographics, cancer history, general health status, QOL, social support, coping efforts, sexual functioning and reproductive concerns.

Quality of life General health QOL and cancer-specific QOL were measured. (a) General QOL was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) 36-item health survey (SF-36) (8, 9). In this study population, internal consistency ranged from 0.84 to 0.93 for the eight subscales. (b) Cancer-specific QOL was assessed using Quality of Life-Cancer Survivorship (QOL-CS), a 46-item scale that includes four QOL domains: physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being (10). In this study population, the overall internal consistency was excellent (alpha = 0.92), with subscale alphas ranging from 0.72 to 0.89.

Psychological distress was evaluated using two different measures: (a) general distress was measured using the mental health subscale from the SF-36 (psychometric properties noted above), and (b) cancer-specific distress, measured by the Impact of Event Scale (IES), a widely used 15-item Likert-scale to measure distress related to cancer (11). In this population, the IES had good internal consistency (alpha = 0.91).

Social support was assessed by the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL), a well-validated self-report measure of perception of instrumental and emotional support (12). In this study, internal consistency was 0.89.

Sexual functioning was measured using the Gynecologic Problems Checklist (GPC), developed for this study to identify the type and extent of gynecologic-specific problems. The GPC consists of two subscales: gynecologic problems (alpha = 0.64) and sexual dysfunction (alpha = 0.88).

Coping efforts were evaluated by the 24-item Coping Orientations to Problems Experienced (COPE) scale (13). In this study, alpha for the total score was .92.

Self-reported infertility was measured by four questions focusing on “how many children the participant had before and after getting cancer” and “how much the participant wanted to have children/more children before and after getting cancer” (e.g., rated on a 5-point scale “not at all” to “very much”).

Reproductive concerns were measured by a scale developed specifically for this study in order to more closely examine concerns among survivors whose reproductive ability may have been impaired or removed due to disease and/or treatment. The initial draft of the scale was based on prior cancer infertility literature and cognitive interviews conducted on nine female content experts (survivors and health care providers). Follow-up focus interviews included participants’ ratings of perceived importance and satisfaction with the topic/concept of each item on the scale, resulting in further item refinement (14). The subsequent three iterations were generated based on female cancer survivors’ feedback, yielding a 14-item measure that is scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale format. All items have the same range of response categories: 0 = “Not at All,” 1 = “A Little Bit,” 2 = “Somewhat,” 3 = “Quite a bit,” and 4 = “Very Much.” A total reproductive concerns scale (RCS) score was produced by summing responses to all 14 items (range 0–56), such that a high score represents more reproductive concerns. Based on our sample of 231 long-term female cancer survivors, internal consistency for this scale was 0.91. Internal consistency among controls (N = 148) was 0.81.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics such as frequencies, means, medians, standard deviations, and ranges were generated to examine the sociodemographic, medical, psychological, and QOL variables. Comparisons of demographic and psychosocial data were conducted using the t-test for continuous variables, Likelihood Ratio Chi-Square test for unordered categorical variables, and Fisher’s Exact test for dichotomous variables. The Bonferroni method was used to adjust significance values, maintaining an overall 5% type 1 error, when comparisons between the three groups were made (i.e., cervical, lymphoma, and GTT groups). Univariate analysis (Pearson product moment correlations) was used to determine the relationships between quality of life and reproductive variables. A stepwise multiple regression method was used to investigate the importance of participant’s age, type of diagnosis, social support, gynecologic problems, and reproductive concerns variables as independent predictors of the dependent variable QOL. All analyses were conducted using SAS for Windows, Version 8.2.

Results

As noted in Table 1, cervical cancer study participants were significantly more likely to be older at diagnosis and interviewed at an older age than lymphoma, GTT, or control study participants. The majority of all study participants were Non-Hispanic White, with 51% from the U.S. and 49% from the U.K.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics, mean ± standard deviation, of survivors (N = 231) and controls (N = 148)

| Variables | Cervical (n = 51) |

Lymphoma (n = 69) |

GTT (n = 111) |

Controls (n = 148) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) |

37.1 ± 5.3* | 32.7 ± 8.3† | 29.8 ± 5.4 | |

| Age at interview (years) |

45.0 ± 5.3‡ | 40.7 ± 8.0† | 36.9 ± 5.6 | 40.1 ± 7.9§ |

| Time since diagnosis | 8.0 ± 1.8 | 8.0 ± 1.3 | 7.2 ± 2.2 | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 46 (90.2) | 63 (91.3) | 106 (96.4) | 138 (93.8) |

| Hispanic | 4 (7.8) | 3 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) |

| Other | 1 (2.0) | 3 (5) | 4 (3.6) | 8 (5) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 31 (60.7) | 54 (78.2) | 90 (81.8) | 106 (72.6) |

| Education | ||||

| HS graduate or less | 13 (25.4) | 22 (31.8) | 20 (23.2) | 25 (16.8) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 39 (76.5) | 60 (86.9) | 69 (62.2) | 120 (81.7) |

Cervical > Lymphoma, GTT (P<.05).

Lymphoma > GTT (P<.05).

Cervical > Lymphoma, GTT, Controls (P<.05).

Controls > GTT (P<.05).

Among the cancer survivors, having more reproductive concerns was significantly associated with poorer physical and mental health on the SF-36 and the QOL-CS (P<.001), greater gynecologic problems (P<.01), more cancer-specific distress (P<.001), and less social support (P<.001). The magnitude of association for each measure with the RCS was between .26 and .38, suggesting a modest but significant relationship (or suggesting that reproductive concerns, while associated significantly with more general problems and concerns, are unique to a large degree).

Multivariate regression analysis results revealed that social support, gynecologic problems, and reproductive concerns significantly predicted individual differences in overall quality of life even when age at diagnosis and type of diagnosis were taken into account (Table 2). These three variables accounted for 63% of the variance in QOL scores. Specifically, women who reported less social support, more gynecologic problems and more reproductive concerns reported significantly worse overall QOL.

Table 2.

Predictors of quality of life (N = 231)*

| Variables | B coefficient | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social support | 0.10 | 142.52 | <.001 |

| Gynecologic functioning | − 0.10 | 33.01 | <.001 |

| Reproductive concerns | − 0.03 | 28.16 | <.001 |

Overall F value: 98.02, P<0.001.

Adjusted R square: 0.63.

Table 3 presents the proportion of survivors who reported at least “somewhat” of a problem on each of the 14 reproductive concerns included in the RCS. The most frequently endorsed problems, identified by more than one-fourth of the survivor sample, included: loss of control over reproductive future, discontent with the number of children, and inability to talk openly about fertility. The least frequently endorsed problems related primarily to assigning guilt or blame, endorsed by fewer than 10% of the sample.

Table 3.

Percentages of survivors endorsing each RCS item*

| RCS items | % |

|---|---|

| Loss of control over reproductive future | 40 |

| Discontent with number of children | 30 |

| Inability to talk openly about fertility | 27 |

| Illness affected ability to have children | 18 |

| Sad about inability to have children | 15 |

| Frustrated ability to have children affected | 13 |

| Angry ability to have children affected | 11 |

| Mourned loss of ability to have children | 11 |

| Concerns of having children | 11 |

| Guilt about reproductive problems | 8 |

| Less satisfied w/life because of problem | 8 |

| Less of a woman | 6 |

| Blame self for reproductive problems | 6 |

| Others are to blame for reproductive problems | 4 |

as “ Somewhat to Very Much ” problem (N = 231).

RCS = reproductive concerns scale.

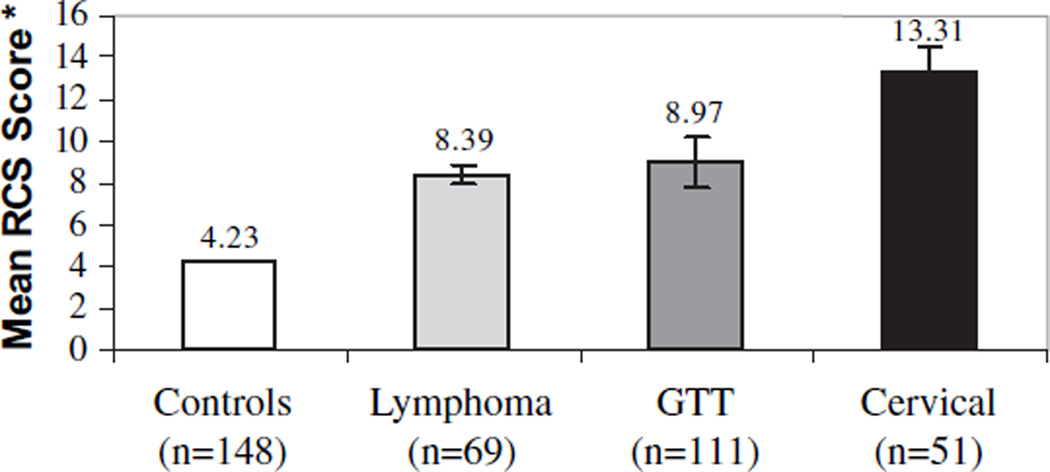

Figure 1 displays average RCS scores for each of the defined study groups. As expected, cancer survivors expressed significantly more reproductive concerns than the control participants (survivors: M = 9.76, SD = 11.64; controls: M = 4.23, SD = 5.78) (P<.001). Among the three cancer survivor groups, cervix cancer survivor scores were higher than those for survivors of GTT or lymphoma, although the difference was not statistically significant. Scale means were not significantly different between the U.S. versus U.K. participants. Item analyses suggested that this elevation in scores among the cervical cancer survivors appeared to be influenced by feelings of anger and grief related to loss of reproductive ability.

Fig. 1.

Reproductive concerns (RCS) scale means and standard error bars for controls and survivor groups. Higher means indicate more reproductive concerns (range = 0–56). Survivors > Controls (P<.001). No significant difference between three survivor groups. GTT; Gestational trophoblastic tumors.

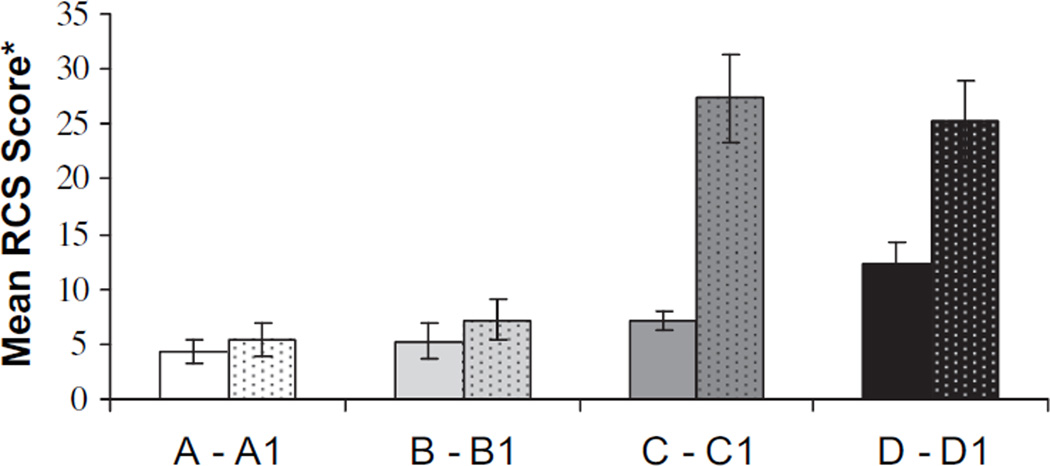

To evaluate a possible association between infertility, reproductive concerns, and QOL, we compared RCS scores among the survivor study participants to those who specified that they “very much” wanted children after cancer (N = 89 of 231). Fig. 2 summarizes an analysis of the relationship between parenthood status prior to and after cancer and reproductive concerns.

Fig. 2.

Reproductive concerns scale (RCS) means and standard error bars based on presence and absence of children prior to and after cancer. Higher means indicate more reproductive concerns (range = 0–56). A) Survivors who did not check “very much” and who had children before and after cancer diagnosis (n = 33) (mean = 4.30). B) Survivors who did not check “very much” and who had children only after cancer diagnosis (n = 49) (mean = 5.28). C) Survivors who did not check “very much” and who had children only before cancer diagnosis (n = 101) (mean = 7.11). D) Survivors who did not check “very much” and who never had children (n = 41) (mean = 12.32). A1) Survivors who “very much” wanted children and who had children before and after cancer diagnosis (n = 23) (mean = 5.47). B1) Survivors who “very much” wanted children and who had children only after cancer diagnosis (n = 42) (mean = 7.19). C1) Survivors who “very much” wanted children and who had children only before cancer diagnosis (n = 14) (mean = 27.36). D1) Survivors who “very much” wanted children and who never had children (n = 10) (mean = 25.20). C1 > A1; B1 (P<.001); D1 > A1; B1 (P<.001); D > A, B, C (P<.05).

As illustrated in Fig. 2, women were divided into four groups according to childbearing status prior to and after cancer: group A and A1—survivors who had children before and after cancer; Group B and B1—survivors who had children only after cancer; Group C and C1—survivors who had children only before cancer; and Group D and D1—survivors who never had children. As predicted, those women who “very much” wanted to have children after cancer but were unable to do so reported significantly more reproductive concerns than those who were able to have children subsequent to cancer (P<.001).

In addition, self-reported infertile women were significantly more likely to report poorer mental health (P<.05), more cancer-specific distress (P<.01), and significantly lower overall (P<.001), physical (P<.01), and psychological (P<.001) well-being than those without self-reported fertility problems. This significance also extended into coping efforts, with those desiring children but unable to reproduce subsequent to cancer endorsing significantly more coping efforts as a result of the cancer (P<.001).

Conclusions

To date, few studies have examined the relationship between fertility outcomes and quality of life after cancer treatment. In this study we were able to link reproductive concerns to quality of life many years after cancer treatment. Even after controlling for disease and psychosocial variables, reproductive concerns continued to be significantly related to long-term quality of life. This suggests that there may be a need for more formalized intensive counseling both prior to and after cancer treatment to aid patients in resolving or managing psychosocial sequelae resulting from unplanned infertility.

As one would expect, compared to controls with no history of cancer, all three survivor groups identified significantly more reproductive concerns that primarily relate to a sense that procreativity has been cut short by cancer, as well as a sense of sadness and difficulty talking about fertility (Table 3). Feelings such as guilt and blame (self or other) were less common. Interestingly, however, we were also able to distinguish between survivor groups based on survivors’ reproductive desire and capacity, where women who wanted to conceive after cancer, but were not able to, reported significantly more reproductive concerns than those who were able to reproduce after cancer. Although the numbers are small, these preliminary data suggest that there may be two important subgroups of survivors to monitor for reproductive distress and intervention: (a) those who had at least one child prior to cancer and desired more, but were unable to complete childbearing due to the cancer and/or its treatment (Fig. 2, Group C1; P<.001); or (b) those who “very much” desired children prior to cancer, had none prior, and were unable to reproduce subsequently (Fig. 2, group D1; P<.001).

It was surprising to find that survivors who had children prior to cancer were more distressed about their subsequent infertility than those who had no children prior to cancer and were also infertile. Although caution should be exercised given the small numbers in these two categories, one might speculate that an inability to complete a family may be at least as distressing as the inability to start a family. Implications for care or counseling around issues of infertility in this population, however, remain relatively unexplored.

While overall, across the entire sample, the magnitude of reproductive concerns was low, there appear to be important subgroups of women specifically distressed about lost fertility. These women can easily be identified by asking whether they wanted more children than they currently have. It is notable that among the most distressed women, mean scores were in the moderate range. Overall, we might anticipate that RCS scores would be higher for a greater number of women with a shorter follow-up time frame after cancer treatment.

This study has several methodologic and measurement weaknesses that limit the strength of our interpretations and capacity to generalize the findings. For example, our use of multiple recruitment methodologies may have created a selection bias (i.e., population-based versus clinic-based). However, once located, participation rates among all survivor cohorts was high (ranging from registry 88% to clinic-based >95%). Perhaps the greater concern is the valuable information that is missing from the long-term survivors who could not be located. It is impossible to generalize to this substantial number (>50%) of women whom we were unable to locate, or to speculate regarding their health and fertility outcomes. Similar methodologic concerns apply to ascertainment of controls, since the majority of survivors did not want to provide names of age-matched acquaintances.

A longitudinal design could assist in answering many of these critical follow-up questions. Further, the issue of reproductive concerns and its relationship with other health outcomes (e.g., type of cancer treatment and type and quality of care) should be tested with other cancer survivor populations who have large numbers diagnosed during childbearing age (e.g., breast cancer), or adult survivors of childhood cancer. In addition, further measurement development and validation is necessary (e.g., test–retest reliability and sensitivity to change over time).

We believe this initial attempt to illustrate the relationship between reproductive concerns and QOL among cancer survivors is worthy of additional investigation to ultimately assist vulnerable cancer survivor populations, such as those living with the threat of infertility. Results from this preliminary study suggest that reproductive concerns, or the aftermath of infertility post cancer treatment, may be a prominent life-altering negative influence many years after the cancer has been treated and the disease has been cured.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute Office of Cancer Survivorship (NCI #3 P30 CA46934–10S2P30), United States; Yorkshire Cancer Research, Cancer Appeal, Weston Park Hospital, and Charing Cross Hospital, United Kingdom.

Contributor Information

Lari Wenzel, University of California, Irvine, Center for Health Policy Research, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, Irvine, CA.

Aysun Dogan-Ates, University of California, Irvine, Center for Health Policy Research, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, Irvine, CA.

Rana Habbal, Epidemiology Division, University of California, Irvine, College of Medicine, Irvine, CA.

Ross Berkowitz, William H. Baker Professor of Gynecology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; New England Trophoblastic Disease Center, Trophoblastic Tumor Registry, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gillette Center for Women’s Cancers, Brigham and Women Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Donald P. Goldstein, New England Trophoblastic Disease Center, Trophoblastic Tumor Registry, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gillette Center for Women’s Cancers, Brigham and Women Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Marilyn Bernstein, New England Trophoblastic Disease Center, Trophoblastic Tumor Registry, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gillette Center for Women’s Cancers, Brigham and Women Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Brenda Coffey Kluhsman, Department of Health Evaluation Sciences, Penn State-Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, College of Medicine, Hershey, PA.

Kathryn Osann, Department of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA.

Edward Newlands, Gestational Trophoblastic Disease Centre, Charing Cross Hospital, Imperial College London, UK.

Michael J. Seckl, Gestational Trophoblastic Disease Centre, Charing Cross Hospital, Imperial College London, UK

Barry Hancock, Yorkshire Cancer Research Professor of Clinical Oncology, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK.

David Cella, Institute for Health Services Research and Policy Studies, Northwestern University and Center on Outcomes, Research and Education, Evanston Northwestern Healthcare, Evanston, IL.

References

- 1.Schover LR. Psychosocial issues associated with cancer in pregnancy. Semin Oncol. 2000;27:699–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schover LR, Rybicki LA, Martin BA, Bringelsen KA. Having children after cancer: a pilot survey of survivors’ attitudes and experiences. Cancer. 1999;86:697–709. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990815)86:4<697::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wenzel L, Berkowitz R, Habbal R, Newlands E, Hancock B, Goldstein DP, et al. Predictors of quality of life among long-term gestational trophoblastic disease survivors. J Reprod Med. 2004;49:589–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wenzel L, DeAlba I, Habbal R, Kluhsman B, Fairclough D, Krebs L, et al. Quality of life in long term cervical cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.01.010. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wenzel L, Berkowitz R, Robinson S, Goldstein D, Bernstein M. The psychological, social and sexual effects of gestational trophoblastic disease on patients and their partners. J Reprod Med. 1994;39:163–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenzel L, Berkowitz R, Robinson S, Bernstein M, Goldstein D. The psychological, social and sexual consequences of gestational trophoblastic disease. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;46:74–81. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kornblith AB, Anderson J, Cella DF, Tross S, Zuckerman E, Cherin E, et al. Hodgkin’s disease survivors at increased risk for problems in psychosocial adaptation. Cancer. 1992;70:2214–2224. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921015)70:8<2214::aid-cncr2820700833>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston (MA): Nimrod; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ware JEJ, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston (MA): The Health Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrell BR, Hassey-Dow K, Leigh S, Ly J, Gulasekaram P. Quality of life in long-term cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22:915–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman HM. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: theory, research, and applications. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warnecke RB, Ferrans CE, Johnson TP, Chapa-Resendez G, O’Rourke DP, Chavez N, et al. Measuring quality of life in culturally diverse population. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1996;20:29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]