Abstract

Aims

To determine whether a behavioral weight reduction intervention improves non-urinary incontinence (UI) lower urinary tract storage symptoms (LUTS) including urinary frequency, nocturia, urgency, at 6 months compared to a structured education program (control group) among overweight and obese women with UI.

Methods

The Program to Reduce Incontinence by Diet and Exercise (PRIDE) was a randomized clinical trial of 338 overweight or obese women with UI. Participants were randomized to 6-month behavioral weight loss intervention (N=226) or control (N=112). All participants received a self-help behavioral treatment booklet for improving bladder control. In this secondary data analysis, we examined changes in non-UI LUTS from baseline to 6 months and the impact of treatment allocation (intervention versus control), weight loss, and physical activity.

Results

Non-UI LUTS were common at baseline varying from 48 to 62 percent. For both groups combined, women experienced significant improvement in nocturia, urgency and International Prostate Symptom Score at 6 months (all P < 0.001). However, LUTS outcomes at 6 months did not differ between intervention and control group. Similarly, no differences were observed based on either the amount of weight lost (≥5% compared to <5%) or physical activity (≥ 1500 kilocalorie expenditure /week compared to < 1500 kilocalories).

Conclusion

LUTS were common among overweight and obese women with UI, with prevalence decreasing significantly after 6 months independent of treatment group assignment, amount of weight lost or physical activity. These improvements may be due to self-help behavioral educational materials, trial participation, or repeated assessment of symptoms.

Keywords: weight loss, lower urinary tract symptoms, randomized control trial

Introduction

The association of obesity and urinary incontinence (UI) in women (1–3) and the beneficial effect of weight loss on UI have been reported. (4, 5) Obesity also has a strong positive association with non-UI LUTS including daytime urinary frequency, nocturia, and urinary urgency. (6, 7) Non UI-LUTS produce a significant adverse effect on quality of life, increase the risk of hip fracture (8), reduce work productivity (9) and cost over $20 billion annually to treat. (1, 10) Interestingly, obese women may be more bothered by non-UI LUTS than non-obese women, possibly related to lack of mobility. (11) Several small studies have shown that both increased physical activity (12) and surgically-induced weight loss improve non-UI LUTS. (13) Weight loss and increased physical activity together, if effective, are attractive intervention options to improve non-UI LUTS as they are non-invasive and have been shown to improve other important adverse health outcomes. (14) However, the effect of a weight loss and physical activity intervention on non-UI LUTS remains uncertain.

We previously conducted a randomized clinical trial of a behavioral weight reduction intervention in overweight and obese women with UI which resulted in reduced episodes of UI compared to a structured health education control intervention. (4) In this secondary data analysis, we compared the effects of this behavioral weight reduction intervention with the control intervention on changes in non-UI LUTS. We hypothesized that the intensive behavioral weight reduction intervention would improve non-UI LUTS compared to the control intervention.

Materials and Methods

The Program to Reduce Incontinence by Diet and Exercise (PRIDE) study was a randomized clinical trial that evaluated the effect of a lifestyle and behavior change intervention for weight loss compared to a structured health education program in overweight or obese women with UI. The design of the study and the results of the study have been described previously. (4)

Participants

Women were eligible if they were at least 30 years of age, had a body mass index (BMI,kg/m2) of 25–50, and at baseline reported 10 or more UI episodes on a 1-week voiding diary (Figure 1). Women were excluded from the study if they reported use of medical therapy for UI or weight loss within the previous month, current urinary tract infection or four or more urinary tract infections in the previous year, a history of UI related to neurologic or functional cause, previous surgery for UI, pregnancy or parturition in the previous 6 months, diabetes requiring medical therapy, or hypertension uncontrolled by medication.

Figure 1.

PRIDE study participants flow diagram.

Between July 2004 and April 2006, 338 women from local communities of Providence, Rhode Island, and Birmingham, Alabama, were recruited for the trial. Participants were randomized using a ratio of 2:1 to either an intensive 6-month behavioral weight loss program or to a structured 4-session education program (control group). Institutional review board approval was obtained at the coordinating center and both clinical sites (Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, and University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama) and each participant provided written informed consent.

Interventions

The intensive weight loss program was designed to produce an average weight loss of 7–9% of initial body weight by 6 months. At 6 months, women in the intervention group had a mean weight loss from baseline of 8% (7.8 kg) compared with 1.6% (1.5 kg) in the control group (P<0.001). Women attended weekly 1-hour expert-led group sessions focused on nutrition, exercise and behavior change. This program included a reduced calorie diet (1200–1500 kcal per day), with a goal of providing no more than 30% of the calories from fat. Participants were also encouraged to increase physical activity such as brisk walking or similar intensity exercise until they were active for at least 200 minutes per week. Women assigned to the control group participated in 4 one-hour educational sessions over the 6 months, which included general information regarding weight loss, physical activity, and healthy eating habits.

At randomization, all participants were given a self-help behavioral treatment booklet with instructions for improving bladder control. (15) The booklet provides basic information about UI and step-by-step instructions on completing voiding diaries, pelvic floor muscle exercises, and techniques to prevent stress and urge UI and control urinary urgency. UI or non-UI LUTS were not discussed further in the control group or weight loss intervention.

Outcomes

All demographics and outcomes were obtained at baseline and after 6 months of study participation. Non-UI LUTS, including daytime urinary frequency, nocturia, and urinary urgency, were measured by a participant-completed 7-day voiding diary and self-report questionnaires completed at baseline and 6 months. Using standard definitions, (16, 17) daytime urinary frequency was defined as urinating 8 or more times during waking hours; nocturia as urinating 2 or more times per night; and urinary urgency as experiencing a sudden strong urge to urinate without leakage at least weekly. The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), which has been validated for use in women, was administered to obtain the composite outcome of non-UI LUTS. (18) Women with an IPSS ≥ 8 were defined as having non-UI LUTS. (19) Incident cases of non-UI LUTS were defined as those that developed de novo over the 6 month study period, whereas remission was defined as cases where non-UI LUTS were present at baseline but were not present at 6 months.

Demographic and health characteristics assessed included: age, race, education level, relationship status, body mass index (kg/m2), type 2 diabetes not requiring medical therapy, current tobacco and alcohol usage, menopause status, hysterectomy history, and parity. The Paffenbarger Activity Questionnaire was utilized to measure physical activity with estimated expenditure greater than 1500 kilocalories/week considered high activity. (20)

Statistical Analysis

We categorized weight loss % into two groups: (weight loss <5%+increase versus weight loss >=5%); we categorized physical activity levels into high and low: (groups:< 1500 kilocalories/week Paffenbarger Score versus >= 1500 kilocalories/week Paffenbarger Score, respectively). We then examined changes in non-UI LUTS from baseline to 6 months in the two randomized groups by comparing symptom change in the treatment groups (intervention versus control), weight loss and physical activity categories.

Chi-square tests were used to compare the proportion of women with non-UI LUTS at baseline and 6 months. Logistic regression was used to assess the odds of remission and new symptom onset at 6 months stratified by non-UI LUTS, treatment group, weight loss and physical activity level.

We performed a sensitivity analysis to determine whether improvement in stress, urge and mixed UI was correlated with improvement in urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia and IPSS. Stress UI remission was marginally associated with urinary frequency remission (Pearson r= 0.16, p=0.06). While UUI remission was marginally associated with urinary frequency (Pearson r= 0.15, p=0.06) and urgency remission (Pearson r= 0.14, p=0.06) and associated with an improvement in IPSS (Pearson r= 0.21, p=0.005). No other significant correlations were observed.

The study had 80% power to detect a 15% to 17% difference between the two treatment groups assuming a type 1 error rate of 0.05 and the failure rate of the comparison group falling between 18% and 52%. Analyses included only participants who completed baseline and follow-up assessments (90% of randomized participants).

Results

There were no significant differences in selected clinical and demographic baseline characteristics between women assigned to the weight-loss program compared to those in the control group (Table 1). Among the overall study cohort, the mean (+/-SD) age was 53 (+/−11) years, mean BMI was 36 (+/−5) (kg/m2) and 77.5% were white. Among the intervention group, 64 women (30%) had weight loss <5% at 6 months while 67 (75%) of the control group did. Among the intervention group, 123 women (56%) had metabolized <1500 kcal/week while 69 (73%) of the control did. Non-UI LUTS were common at baseline, with 48% of women reporting daytime frequency, 50% nocturia, 62% urgency, and 62% reporting an IPSS of greater than or equal to 8. In the overall cohort, the prevalence of non-UI LUTS decreased significantly from baseline to 6 months for nocturia, 51% to 41%, p=0.009; urinary urgency, 62% to 43%, <0.001; IPSS >8, 62% to 37%, p<0.001) but not for daytime frequency (daytime frequency, 51% to 46%, p=0.221).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics of participants by treatment group. There were no significant differences between groups.

| Characteristics | Intervention N=226 |

Usual care N=112 |

|---|---|---|

| Age-year, mean ± std | 53 ± 10 | 53 ± 10 |

| Race | ||

| Non-White | 55 (24) | 21 (19) |

| White | 171 (76) | 91 (81) |

| Education beyond high school-no. (%) | 200 (89) | 93 (83) |

| Relationship status-no. (%) | ||

| Marries or living with a partner | 166 (74) | 90 (80) |

| Single, widowed, or divorced | 57 (26) | 22 (20) |

| Body-mass index - mean ± std | 36 ± 6 | 36 ± 5 |

| Diabetes – no. (%) | 9 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Current smoker – no. (%) | 14 (6) | 4 (4) |

| Current alcohol use – no. (%) | 154 (68) | 74 (66) |

| Postmenopausal-no. (%) | 115 (55) | 62 (58) |

| Hysterectomy-no. (%) | 70 (31) | 29 (26) |

| Parity | 2 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 |

There were no significant differences between women randomized to the intervention versus the control group for all non-UI LUTS outcomes (frequency, nocturia, urinary urgency, IPSS >8) (Table 2). The comparative improvement across treatment designation for frequency, nocturia and urgency ranged from −1% to −6% favoring the intervention group, however none of these comparisons reached statistical significance and the percent improvement was modest.

Table 2.

Non-UI LUTS at baseline and after 6 months by treatment group, amount of weight loss at 6 months and amount of exercise at 6 months.

| Intervention | Control | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | Baseline | 6 months | Net* Effect | |

| Daytime Frequency | 109 (48%) | 93 (43%) | 63 (56%) | 47 (52%) | −1% |

| Nocturia | 112 (50%) | 83 (38%) | 61 (54%) | 47 (48%) | −6% |

| Urinary Urgency | 138 (61%) | 89 (40%) | 71 (63%) | 46 (47%) | −5% |

| IPSS Score ≥ 8 | 137 (61%) | 76 (35%) | 72 (64%) | 40 (41%) | −3% |

| Weight loss <5%+no change+increase | Weight loss >=5% | ||||

| Daytime frequency | 72 (50%) | 56 (43%) | 100 (51%) | 84 (49%) | 5% |

| Nocturia | 73 (51%) | 58 (41%) | 100 (51%) | 72 (41%) | 0% |

| Urinary Urgency | 87 (61%) | 66 (46%) | 122 (63%) | 69 (39%) | −9% |

| IPSS Score ≥ 8 | 89 (62%) | 57 (40%) | 120 (62%) | 59 (34%) | −6% |

| < 1500 kilocalories/week Paffenbarger Score | >= 1500 kilocalories/week Paffenbarger Score | ||||

| Daytime frequency | 93 (50%) | 79 (44%) | 62 (50%) | 57 (48%) | 4% |

| Nocturia | 99 (53%) | 73 (39%) | 58 (47%) | 51 (41%) | 8% |

| Urinary Urgency | 117 (63%) | 87 (47%) | 69 (56%) | 44 (36%) | −4% |

| IPSS Score ≥ 8 | 117 (63%) | 72 (39%) | 72 (59%) | 39 (32%) | −3% |

Reported as number (percent of total)

Daytime frequency = 8 or greater voids during waking hours

Nocturia = 2 or greater voids at night

Net effect compares the percent improvement of non-UI LUTS by treatment group, amount of weight loss at 6 months and amount of exercise at 6 months

None of the net effect comparisons reached statistical significance.

Numbers in groups differ based on completeness of follow-up.

The impact of the amount of weight loss on non-UI LUTS was examined in the entire cohort after 6 months of study participation (Table 2). There were no significant differences in non-UI LUTS outcomes in those participants who lost <5% body weight or had no change or weight gain compared to those who reduced more than 5% of the body weight.

The impact of weekly physical activity on non-UI LUTS was examined by comparing those who reported engaging in activity which expended less than versus greater than 1500 kilocalories per week. (Table 2). No significant differences were seen between groups with high versus low activity.

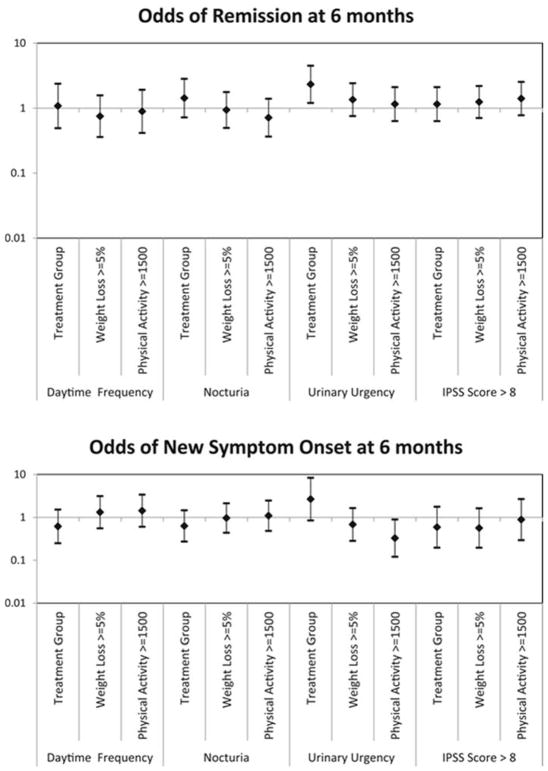

In addition to changes in prevalent cases of non-UI LUTS, the odds of non-UI LUTS remission or new onset (incident) cases, based on treatment group, percent weight loss and activity level was examined (Figure 2). Randomization to the intervention group, percent of weight lost and physical activity level did not influence remission or incident non-UI LUTS cases. Randomization to the intervention group did however increase the odds of remission for participants with urgency (Odds Ratio 2.3, 95% Confidence Interval 1.2–4.4).

Figure 2.

Tornado plots of odds ratios of A. remission and B. new onset (incident) non-UI LUTS, stratified by treatment group, weight loss achieved, and physical activity performed.

Discussion

At 6 months, the overall cohort, regardless of treatment assignment, reported a significant improvement in multiple non-UI LUTS domains. The improvement in self-reported non-UI LUTS was independent of treatment assignment and the amount of weight loss or physical activity suggesting that factor(s) associated with trial participation may have improved non-UI LUTS outcomes. However, the study was not designed to determine whether the self-help behavioral UI treatment intervention received by both groups, completion of the voiding diary, or some other factor may have been responsible for reducing the frequency of non-UI LUTS.

Previous studies have shown an association between LUTS and obesity and physical inactivity. (21, 22) Previously we demonstrated that women enrolled in PRIDE who were randomized to the intensive lifestyle intervention group had significantly reduced UI. The mean weekly number of overall UI episodes decreased by 47% in the intervention group, compared with 28% in the control group at 6 months (P=0.01). Compared with the control group, the intervention group experienced a greater decrease in the frequency of stress-UI episodes (P=0.02).(4)

In contrast to the results for UI, we now report that women assigned the weight-loss intervention did not experience a significantly greater reduction in non-UI LUTS than the control group. Previous longitudinal research has demonstrated the dynamic nature of LUTS, including UI and overactive bladder (OAB) which may in part explain the improvement seen within the overall cohort. (23) In a prospective population-based study spanning 16 years, the incidence of UI and OAB were 21% and 20% respectively, while remission rates were 34% and 43% respectively. (23) Our results are similar, with incidence in 20% and remission in approximately 40%. A systematic review of longitudinal studies found a similar dynamic progression of incidence and remission of urinary symptoms while also demonstrating many patients suffered sustained symptoms over time. (24)

Few studies have examined the effect of an exercise and weight loss intervention on non-UI LUTS. In a study of 21 obese elderly Korean women who underwent a cardiovascular and resistance exercise intervention daily for 52 weeks, participants experienced significant improvements in non-UI LUTS from baseline. (12) At one year, the group lost a mean of 2.6 kg and frequency, nocturia and urgency all improved (35%, 27%, 7% reduction in prevalence, respectively). (12) Women in the weight loss intervention in our current study also experienced improvement in lower non-UI LUTS from baseline to 6 month follow-up, for frequency (5%), nocturia (12%) and urgency (21%), but as noted above, these improvements were not significantly different from those reported by the control group.

In a cohort study at one year after bariatric surgery,(25) 47 women lost a mean of 37.4 kg and reported a significant improvement in overall Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptom score (26), nocturia and urgency; however 15% of women had worse scores at 1 year. They found no correlation between improvement and the degree of weight lost, but did observe a correlation between LUTS improvement and insulin resistance improvement. Interestingly, improvement in urinary symptoms was typically achieved by 6 weeks post-operatively before the majority of weight loss was obtained and the symptoms remained stable until 1 year. Lack of a control group in these other studies makes it difficult to interpret these results.

The strengths of this study include that over 20% of the cohort was non-white and subjects were recruited from 2 different communities likely increasing generalizability. In addition, the behavioral intervention was well designed and achieved desired weight-loss goals. The cohort was well-characterized with patient reported outcomes using validated measures. Several limitations of this research should be noted. All participants in PRIDE had UI at baseline but not all had non-UI LUTS, which may limit our ability to detect change in LUTS in women without UI. Furthermore, study participants were clinical trial volunteers and may differ from the general population. The control group underwent four healthy lifestyle educational sessions which is likely more extensive than what overweight women presenting with LUTS in the general population would receive. This may have diminished the impact of the intervention between groups. This study is a post-hoc secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial with a sample size selected to assess changes in UI, under-powered to detect changes in non-UI LUTS. We made multiple comparisons potentially increasing the risk of type 1 error.

Conclusion

Non-UI LUTS were common among overweight and obese women with UI, with the prevalence decreasing significantly after 6 months independent of treatment group assignment, amount of weight lost or physical activity. Improvements in non-UI LUTS overweight and obese women could be due to the provision of written self-help behavioral educational materials, increased attention to LUTS by way of trial participation and/or repeated assessment of symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: Supported by Grant Numbers U01DK067860, U01 DK067861 and U01 DK067862 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Funding was also provided by the Office of Research on Women’s Health and by Kevan and Anita Del Grande. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Subak received funding from the NIDDK (K24 DK080775 06).

References

- 1.Khullar V, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, Milsom I, Bitoun CE, Coyne KS. The relationship between BMI and urinary incontinence subgroups: results from EpiLUTS. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2014;33(4):392–9. doi: 10.1002/nau.22428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dallosso HM, McGrother CW, Matthews RJ, Donaldson MM, Leicestershire MRCISG. The association of diet and other lifestyle factors with overactive bladder and stress incontinence: a longitudinal study in women. BJU international. 2003;92(1):69–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subak LL, Richter HE, Hunskaar S. Obesity and urinary incontinence: epidemiology and clinical research update. The Journal of urology. 2009;182(6 Suppl):S2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subak LL, Wing R, West DS, Franklin F, Vittinghoff E, Creasman JM, et al. Weight loss to treat urinary incontinence in overweight and obese women. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360(5):481–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subak LL, King WC, Belle SH, Chen JY, Courcoulas AP, Ebel FE, et al. Urinary Incontinence Before and After Bariatric Surgery. JAMA internal medicine. 2015;175(8):1378–87. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alling Moller L, Lose G, Jorgensen T. Risk factors for lower urinary tract symptoms in women 40 to 60 years of age. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2000;96(3):446–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teleman PM, Lidfeldt J, Nerbrand C, Samsioe G, Mattiasson A group Ws. Overactive bladder: prevalence, risk factors and relation to stress incontinence in middle-aged women. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2004;111(6):600–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asplund R. Hip fractures, nocturia, and nocturnal polyuria in the elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2006;43(3):319–26. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sexton CC, Coyne KS, Vats V, Kopp ZS, Irwin DE, Wagner TH. Impact of overactive bladder on work productivity in the United States: results from EpiLUTS. The American journal of managed care. 2009;15(4 Suppl):S98–S107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holm-Larsen T. The economic impact of nocturia. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2014;33(Suppl 1):S10–4. doi: 10.1002/nau.22593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melin I, Falconer C, Rossner S, Altman D. Nocturia and overactive bladder in obese women: A case-control study. Obesity research & clinical practice. 2007;1(3):I–II. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko IG, Lim MH, Choi PB, Kim KH, Jee YS. Effect of Long-term Exercise on Voiding Functions in Obese Elderly Women. International neurourology journal. 2013;17(3):130–8. doi: 10.5213/inj.2013.17.3.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitcomb EL, Horgan S, Donohue MC, Lukacz ES. Impact of surgically induced weight loss on pelvic floor disorders. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(8):1111–6. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1756-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Look ARG, Gregg EW, Jakicic JM, Blackburn G, Bloomquist P, Bray GA, et al. Association of the magnitude of weight loss and changes in physical fitness with long-term cardiovascular disease outcomes in overweight or obese people with type 2 diabetes: a post-hoc analysis of the Look AHEAD randomised clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(11):913–21. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30162-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burgio KLPL, Lucco AJ. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coyne KS, Payne C, Bhattacharyya SK, Revicki DA, Thompson C, Corey R, et al. The impact of urinary urgency and frequency on health-related quality of life in overactive bladder: Results from a national community survey. Value Health. 2004;7(4):455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2004.74008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tikkinen KA, Johnson TM, 2nd, Tammela TL, Sintonen H, Haukka J, Huhtala H, et al. Nocturia frequency, bother, and quality of life: how often is too often? A population-based study in Finland. European urology. 2010;57(3):488–96. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsiao SM, Lin HH, Kuo HC. International Prostate Symptom Score for assessing lower urinary tract dysfunction in women. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(2):263–7. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1818-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breyer BN, Van den Eeden SK, Horberg MA, Eisenberg ML, Deng DY, Smith JF, et al. HIV status is an independent risk factor for reporting lower urinary tract symptoms. The Journal of urology. 2011;185(5):1710–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Wing AL, Hyde RT. Physical activity as an index of heart attack risk in college alumni. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;108(3):161–75. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons JK. Modifiable risk factors for benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms: new approaches to old problems. The Journal of urology. 2007;178(2):395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons JK, Messer K, White M, Barrett-Connor E, Bauer DC, Marshall LM, et al. Obesity increases and physical activity decreases lower urinary tract symptom risk in older men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men study. Eur Urol. 2011;60(6):1173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wennberg AL, Molander U, Fall M, Edlund C, Peeker R, Milsom I. A longitudinal population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in women. European urology. 2009;55(4):783–91. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Chancellor MB, Kopp Z, Guan Z. Dynamic progression of overactive bladder and urinary incontinence symptoms: a systematic review. European urology. 2010;58(4):532–43. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luke S, Addison B, Broughton K, Masters J, Stubbs R, Kennedy-Smith A. Effects of bariatric surgery on untreated lower urinary tract symptoms: a prospective multicentre cohort study. BJU international. 2015;115(3):466–72. doi: 10.1111/bju.12943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson S, Donovan J, Brookes S, Eckford S, Swithinbank L, Abrams P. The Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms questionnaire: development and psychometric testing. British journal of urology. 1996;77(6):805–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]