Abstract

We have utilized hydrogen exchange-mass spectrometry (HX-MS) to characterize local backbone flexibility of four well-defined IgG1-Fc glycoforms expressed and purified from Pichia pastoris, two of which were prepared using subsequent in vitro enzymatic treatments. Progressively decreasing the size of the N-linked N297 oligosaccharide from high mannose (Man8-Man12), to Man5, to GlcNAc, to non-glycosylated N297Q resulted in progressive increases in backbone flexibility. Comparison of these results with recently published physicochemical stability and Fcγ receptor binding data with the same set of glycoproteins provide improved insights into correlations between glycan structure and these pharmaceutical properties. Flexibility significantly increased upon glycan truncation in two potential aggregation prone regions. In addition, a correlation was established between increased local backbone flexibility and increased deamidation at asparagine 315. Interestingly, the opposite trend was observed for oxidation of tryptophan 277 where faster oxidation correlated with decreased local backbone flexibility. Finally, a trend of increasing C’E glycopeptide loop flexibility with decreasing glycan size was observed that correlates with their FcγRIIIa receptor binding properties. These well-defined IgG1-Fc glycoforms serve as a useful model system to identify physicochemical stability and local backbone flexibility data sets potentially discriminating between various IgG glycoforms for potential applicability to future comparability or biosimilarity assessments.

Keywords: formulation, stability, antibody, hydrogen exchange, mass spectrometry, glycosylation

Introduction

Glycosylation is a widespread and complex post-translational modification which introduces structural heterogeneity in recombinant therapeutic proteins.1,2 Development and regulatory approvals of glycosylated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), Fc-fusion proteins, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), and antibody fragments have increased dramatically over the past three decades.3,4 The IgG1 subclass of antibodies, the most abundant in human serum and the most common subclass for approved mAb therapeutics, has a conserved N-linked-glycosylation site at N297 in the constant heavy chain of the Fc region.5–9 N-glycan structures are known to modulate different effector functions of IgG antibodies including antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and antibody clearance by affecting FcγR, C1q and FcRn binding, respectively.10,11 Naturally-occurring N-glycans of IgG1 antibody in the human serum are of the complex, biantennary type (consisting of two arms: one α−1, 3 arm and one α−1, 6 arm) and contain a common seven monosaccharide core (4 N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc), and 3 mannose (Man) residues).12 Glycan heterogeneity in antibodies, arising from site occupancy (symmetric or asymmetric) and also from the type of glycans attached to the common core, governs the binding to various receptors thereby affecting the antibody’s biological functions. For example, the presence of terminal and bisecting GlcNAc and the absence of fucose (Fuc) increases ADCC activity by increasing FcγRIIIa receptor affinity, while increasing terminal sialylation reduces ADCC activity.13 Moreover, the presence of galactosylation (Gal) promotes CDC by increasing interaction with C1q.14 Hence, elucidation of mechanisms underlying these glycosylation effects is an active area of research that could lead to engineering antibodies having desired therapeutic effects.

The therapeutic efficacy of IgG mAb candidates depends on their structural integrity, conformational stability, flexibility and biological functionality. N-glycosylation at N297 of the CH2 domain influences the conformation, flexibility, aggregation propensity and PK/PD properties of therapeutic mAbs, making it essential to evaluate effects of glycosylation on product quality including physicochemical stability and biological efficacy.13,15–18 Recombinant therapeutic mAbs requiring N-glycosylation are typically produced in mammalian expression hosts (e.g., CHO, SP20 and NSO cells).19 Manufacturing conditions need to be tightly controlled to achieve a sufficiently high degree of reproducibility in terms of glycan heterogeneity during mAb production. However, glycan heterogeneity inevitably will still exist in mAbs produced in these recombinant expression systems that could potentially affect product quality.20 For example, recombinant mAbs could have non-human glycans such as N-glycolylneuraminic acid (NGNA) instead of N-acetylneuraminic acid (NANA) or small amounts (ranging from 1%−20%) of high-mannose (Man5-Man9) could affect their biological efficacy. 14,21,22 High mannose (HM) glycoforms of IgG have reduced serum half-life due to binding to mannose receptors, increased ADCC and reduced CDC activities compared to antibodies containing complex fucosylated or hybrid glycans.13,23 Hence, molecular heterogeneities like glycosylation are critical product quality attributes necessitating their close monitoring during therapeutic mAb production, upon manufacturing changes (comparability) and during biosimilar development. Additionally, ensuring protein stability from manufacturing through patient administration is also a critical aspect of therapeutic protein drug development, where physicochemical degradation may lead to loss of potency, aggregation and increased immunogenicity potential.24,25 Hence, not only is it important to understand how glycosylation affects the pharmaceutical stability of antibodies, but also to better understand the inter-relationships between stability and the desired biological activity.

To this end, we generated a series of well-defined, nearly homogenous, IgG1-Fc glycoforms with serially truncated glycans. Previously, we analyzed these glycoproteins using multiple physical, chemical, and receptor binding assays as described in four manuscripts in the February 2016 issue of Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences.16–18,26 Results from this series of studies showed that the glycoform structure not only affected chemical degradation (especially deamidation of N315 and transformation of W277 into glycine hydroperoxide), but also led to different impurity profiles.17 In addition, a correlation between physical stability and in vitro binding activity versus the size of the glycans was also observed. For example, HM-Fc and Man5-Fc had greater physical stability, higher apparent solubility and stronger receptor binding than the GlcNAc and non-glycosylated N297Q-Fc.16,18 These results suggested a strong correlation between decreased length of glycan and decreased apparent solubility, conformational stability and in vitro receptor binding. Finally, these biochemical and biophysical datasets with the four well-defined IgG1-Fc glycoforms were further employed to develop an integrated mathematical model (using data mining and machine learning tools) for biosimilarity analysis.26

In this work, we measured the local backbone flexibility of these four IgG1-Fc glycoforms by hydrogen exchange-mass spectrometry (HX-MS). HX-MS provides information on higher order structure and dynamics by monitoring the rate of backbone amide hydrogen exchanges. Proteolysis following HX produces peptic peptides that are analyzed by LC-MS to assess the deuteration level of each peptide (a measure of flexibility) as a function of time, so that localized differences are obtained at peptide resolution. HX-MS has been used extensively to investigate subtle higher order structural changes and dynamics in mAbs as a consequence of aggregation, reversible self-association, oxidation, excipients and point mutations.27–30 However, only a limited number of studies have examined the effects of glycosylation on flexibility in IgG antibodies.15,31–33 In this work, we correlate the effects of varying glycosylation on structural flexibility (especially in the CH2 domain) as measured by HX-MS with our previously reported results on the overall conformational stability, chemical stability and receptor binding profiles of four well-defined IgG1-Fc glycoforms as described above. These correlations are discussed in the context of developing a better understanding of the interplay between glycosylation, stability, local flexibility and biological function from a pharmaceutical perspective, especially applicability to future comparability or biosimilarity assessments.

Materials and Methods

Preparation and initial characterization of IgG1-Fc glycoforms

We have reported the production of these Fc glycoforms in detail elsewhere.18 Briefly, the IgG1-Fc glycoforms (high-mannose-Fc (HM-Fc), Man5-Fc, GlcNAc-Fc and N297Q-Fc) were prepared by expression of HM-Fc in a glycosylation-deficient strain of Pichia pastoris followed by in-vitro enzymatic digestion of HM-Fc by a α−1, 2-mannosidase or endoglycosidase H (Endo H) to obtain the truncated Man5-Fc or GlcNAc-Fc. For the N297Q non-glycosylated IgG1-Fc, mutagenesis was used to remove the N-linked glycosylation. The proteins were pure (~99% by SDS-PAGE) and had minimal proteolysis products and high molecular weight species (1%−3%) after purification and enzyme truncation. The HM-Fc was heterogeneous, with N-glycans containing 8 to 12 mannose residues (Man8-Man12) at each N297 site; the major glycan was Man8GlcNAc2. The truncated Man5-Fc, GlcNAc-Fc glycoforms and the non-glycosylated N297Q-Fc were well-defined and homogenous. With decreasing glycan size, the HM, Man5, GlcNAc glycoforms of IgG1-Fc and non-glycosylated N297Q-Fc mutant form a well-defined series of model glycoproteins. The purified glycoforms were stored at −80°C in 10 mM histidine buffer containing 10% sucrose at pH 6.0 until utilized for HX-MS studies.

Sample preparation for hydrogen exchange-mass spectrometry

For hydrogen exchange-mass spectrometry studies, all four Fc glycoforms were thawed and then dialyzed into 20 mM citrate-phosphate buffer with ionic strength adjusted to 0.15 by NaCl at pH 6.0. Subsequently, the proteins were concentrated, as described elsewhere.16 The final adjusted protein stock concentration of 1 mg/mL was determined by absorbance at 280 nm as measured by an UV-visible spectrophotometer (Agilent 8453, Palo Alto, California). Components of all buffers including sodium phosphate and sodium chloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO) while citric acid anhydrous and citric acid monohydrate were purchased from Fisher Scientific, all at the highest purity grade. Liquid chromatography grade acetic acid and phosphoric acid, tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), porcine pepsin, guanidine hydrochloride, and deuterium oxide (99+%D) were purchased from Fluka/Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri). Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-grade formic acid (+99%) was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, Illinois). LC-MS-grade water, acetonitrile, and isopropanol were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, New Jersey).

Deuterated labeling buffer preparation

Deuterium-based labeling buffer contained 0.15 M sodium chloride, and 20 mM citratephosphate at pH 6.0 in 99.9 atom % D2O. The pH of the buffer was then measured and adjusted by adding 0.4 units to the pH meter reading to obtain the pD value.34 The same batch of buffer was used for HX experiments for all the four IgG1-Fc glycoforms to avoid any variation in the buffer properties.

HX-MS

Hydrogen exchange was performed using an H/DX PAL robot (LEAP Technologies, Carrboro, North Carolina) and MS measurements were conducted using a QTOF mass spectrometer (Agilent 6530, Santa Clara, California) with Agilent 1260 Infinity LC System as described previously.35 For HX, deuterium labeling of 3 μL each of the IgG1-Fc glycoproteins, held at 20 μM concentration was performed by adding 27 μL of deuterated labeling buffer at 25°C in triplicate. The above exchange reactions were quenched at 1°C by 1:1 dilution of the labelled proteins by a quench buffer (containing 4 M guanidine hydrochloride, 1M TCEP and 0.2 M sodium phosphate at pH 2.5) after incubation for 5 labeling times: 15 s, 102 s, 103 s, 104 s and 86400 s. Subsequently, the quenched samples were digested on an immobilized pepsin column that was prepared in-house.36 Carry-over from the pepsin column was removed between samples using a two-wash cocktail method as previously described.37 A standard LC-MS procedure for HX-MS35 was used and all the measurements were made relative to HM-Fc glycoform, which was run in parallel on the same day with each of the three other glycoforms as a control for day-to-day variability.

Peptide mapping

Prior to HX-MS analysis, a combination of accurate mass measurements and collision induced dissociation (CID) with tandem MS was used to identify a total of 51 peptic peptides listed in Supplemental Table S1. These peptides covered 100% of the amino acid sequence of the IgG1-Fc glycoforms. Since glycopeptides tend to undergo glycan fragmentation instead of backbone cleavage during collision induced dissociation (CID), characteristic oxonium ions of the respective glycopeptides were utilized to confirm the identity of each glycopeptide.38,39

Deuteration controls

Maximum deuterium recovery for each peptide was estimated separately using highly deuterated peptides. The deuteration controls of each peptide belonging to each glycoform were prepared separately collecting peptic peptides following pepsin column digestion. The peptides were subsequently dried in a vacuum concentrator and reconstituted in H2O buffer, at pH 6.0. The peptides were then deuterium labeled for 4 h and analyzed as standard samples. Based on the deuteration controls, the deuterium recovery ranged between 31% and 81% where the first amide in each peptide is treated as a rapid back-exchanger.

HX-MS data analysis

Initial peptide LC-MS feature extraction and centroid calculations were performed using HDExaminer (Sierra Analytics, Modesto, CA). All MS results were individually inspected to ensure reliability. Retention time window adjustments were manually applied as needed. Additional numerical and statistical analysis was carried out in Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). The extent of HX was quantified on a percentage basis with back-exchange correction:

| (1) |

where denotes peptide centroid mass and t is the HX time. m is the mean of the centroid value from triplicate measurements, m0 is the theoretical centroid mass of the undeuterated peptide, and is mean of the centroids obtained from the deuteration control.

Differential exchange values at each HX time, ΔHXt, representing the difference in HX for each peptide of each IgG1-Fc glycoform (subscript g) relative to the same peptide in the HM-Fc (subscript HM-Fc) is given by:

| 2 |

For mapping HX effects onto an Fc homology model, HX data from all time points for each peptide were averaged into a single value, ΔΗΧ, representing the average difference in HX between Man5-Fc, GlcNAc-Fc and N297Q-Fc relative to HM-Fc:

| 3 |

where the index i covers the range of discrete HX times ti. A threshold limit of three times the propagated standard error was used to identify significant changes in HX; see Supporting Information for calculations of estimating the significance limit. For overlapping peptides covering the same residues, significant differences took precedence over insignificant results. There were no cases of significant differences of opposite sign, i.e., no cases where both significantly faster and slower exchange were observed in overlapping peptides.

Homology model

The X-ray structure of the IgG1-Fc from Thr108-Lys330 (PDB ID: 1HZH)40 was used as the template for the Fc homology models. The sequence identity was 100%, except for N297Q-Fc.

Results

Hydrogen exchange (HX) was used to probe the backbone flexibility of IgG1-Fc as a function of N-linked glycosylation in four Fc constructs with different glycosylation: high mannose (HM), Man5, GlcNAc and non-glycosylated (N297Q). Following a quench of the HX reaction, the labeled samples were digested with pepsin to reproducibly obtain a total of 51 IgG1-Fc peptides. The deuterium content of each peptide was determined by LC-MS. These peptides gave 100% sequence coverage for the constant heavy chain of each of the four IgG1-Fc glycoforms.

Direct effects of N-glycosylation on Fc backbone flexibility at the glycosylation site

Direct analysis of the HX kinetics of the Fc backbone at the site of glycosylation is a desirable target, and although some interesting trends were observed for the glycan containing peptides in this work (see Supporting Information; Supplemental Figures S1 and S2), several unresolved technical issues make quantitative comparisons between different glycopeptides problematic. First, the acetamido groups of the glycans and the linking asparagine will retain deuterium.41 The different glycoforms examined here have different numbers of acetamido groups that may retain deuterium to different extents. Deuteration controls cannot compensate for labeling of the acetamido groups since the fraction of deuterium on backbone amides cannot be determined. Glycosylation is also known to have an effect on chemical exchange.41 Rates of HX in peptides with different chemical exchange kinetics cannot be compared unless the chemical exchange effect is compensated.35,42 Finally, although these artifacts are likely to be minimal in the case of the Man8-Man12 glycans in the HM-Fc, there remains heterogeneity in HM-Fc since a given glycoform on one chain will be matched with each glycoform on the other chain. Thus each glycoform is an ensemble average. In summary, for these reasons, although the observed HX results for glycan-containing peptides display some suggestive trends in terms of glycan size and effects on local flexibility of the glycosylation site, these results will not be quantitatively interpreted here and such comparisons will be the focus of future work.

Glycosylation has indirect effects on Fc backbone flexibility

HX Kinetics:

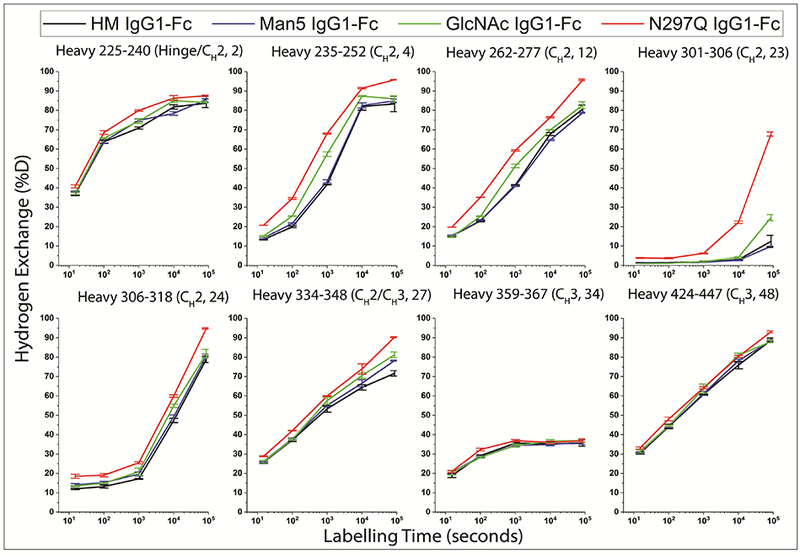

The hydrogen exchange kinetics for eight representative peptides of each of the four IgG1-Fc glycoforms are shown in Figure 1 and the results are summarized and compared in Table 1. The rates of HX in these regions provide a qualitative measure of the backbone dynamics of the IgG1-Fc proteins. For example, peptide 23 (HC residues 301–306) and peptide 34 (HC residues 359–367) in the X the protein backbone is more dynamic. As shown in Figure 1 and Table 1, the HX rate is perturbed by differential glycosylation. Overall, these results indicate that as the size of the glycan attached to N297 is truncated from HM or Man5 to GlcNAc (or is completely removed in N297Q-Fc), the backbone flexibility in these CH2 domain regions increases. In contrast, the extent of glycosylation did not have a substantial effect on CH3 domain peptides 34 and 48, except that HX was slightly faster in these regions for N297Q-Fc. This result suggests that complete removal of the glycan causes increased flexibility of the CH3 domain as well, which is distal from the glycosylation site in the Fc structure.

Figure 1:

HX kinetics of representative peptides found in the four IgG1-Fc glycoforms. The extent of HX has been corrected for back-exchange using deuteration controls as defined by equation (1). The error bars represent sample standard deviation from three independent HX measurements.

Table 1:

Summary and comparison of HX rates of representative peptides (generated by pepsin digestion of the well-defined IgG1-Fc glycoforms) from Figure 1. Identity of peptic peptides derived from IgG1-Fc glycoforms are based on Eu numbering system.5,6,8

| Peptide Number |

Starting residue number |

Ending residue number |

Fc Domain Location | Rank ordering of HX rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 225 | 240 | Hinge-CH2 | N297QFc> GlcNAcFc≈Man5Fc≈HMFc |

| 4 | 235 | 252 | CH2 | N297QFc> GlcNAcFc>Man5Fc≈HMFc |

| 12 | 262 | 277 | CH2 | N297QFc> GlcNAcFc> HMFc>Man5Fc |

| 23 | 301 | 306 | CH2 | N297QFc> GlcNAcFc>Man5Fc≈HMFc |

| 24 | 306 | 318 | CH2 | N297QFc> GlcNAcFc>Man5Fc≈HMFc |

| 27 | 334 | 348 | CH2/ CH3 | N297QFc> GlcNAcFc>Man5Fc≈HMFc |

| 34 | 359 | 367 | CH3 | N297QFc> GlcNAcFc≈Man5Fc≈HMFc |

| 48 | 424 | 447 | CH3 | N297QFc> GlcNAcFc≈Man5Fc≈HMFc |

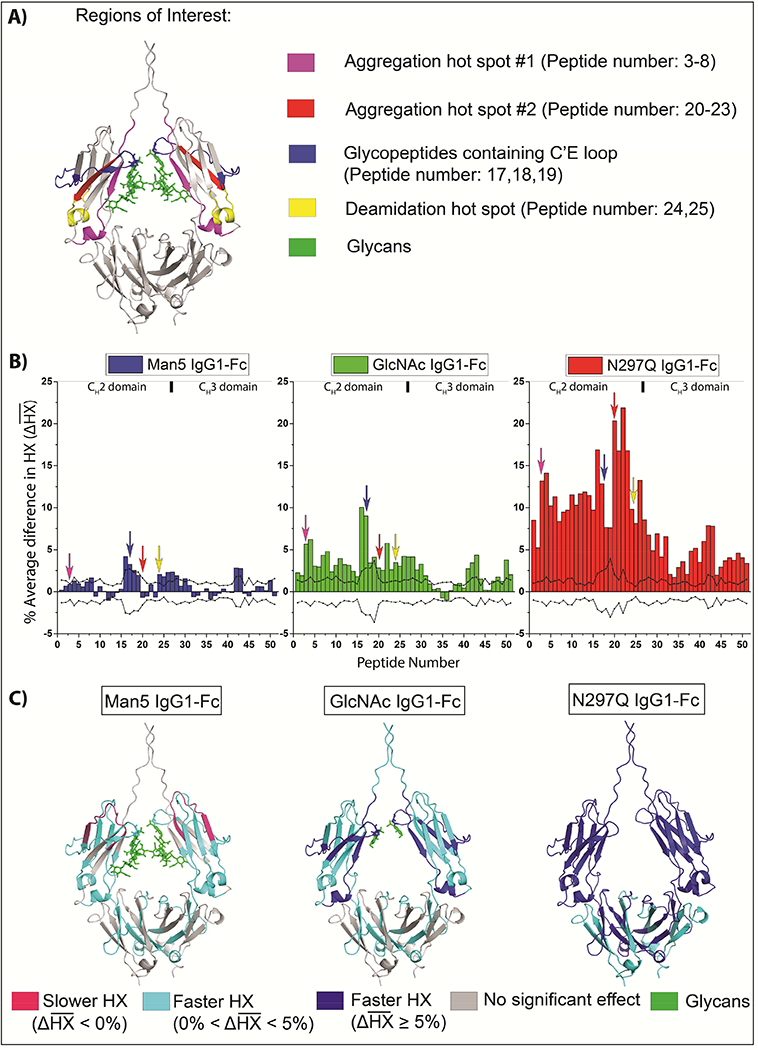

Figure 2 summarizes the HX results and correlates them with regions of the Fc that are critical to stability and function. The regions, shown in Figure 2, panel A, include two aggregation hot spots (as determined by correlation to aggregation propensity shown in previous work29,30 ), a deamidation prone NG site at N315 (shown previously17), and the glycopeptide-containing C’E loop residues (the C’E site is essential for the Fc receptor binding, also shown in previous work43,44) in the CH2 domain of IgG1-Fc. To better display the HX effects of all 51 peptides relative to each IgG1-Fc glycoform, Figure 2, panel B shows the difference plots of HX effects as a function of glycosylation using the average HX difference across all time points compared to the high mannose Fc control , as defined by equation (3). The peptides are indexed from the N- to C-terminus and represented on the horizontal axes (differential HX data at each individual HX time, as defined by (2) are shown in the Supporting Information; Supplemental Figure S3 and the locations and sequences of each peptide are provided in Supporting Information; Supplemental Table S1). A positive value for a peptide indicates faster exchange and thus an increase in backbone flexibility of that region in the glycoform compared to the high mannose form, while a negative value indicates slower exchange and thus decreased backbone flexibility compared to the high mannose form. The dashed lines in Figure 2, panel B indicate the limits for statistical significance as defined in the Supporting Information. The significant differences in for each IgG1-Fc glycoform as compared with HM-Fc are mapped onto a homology model in Figure 2, panel C. For overlapping peptides with conflicting results, significant changes were given priority (see Methods). For example, peptide 8 of Man5-Fc that spans the aggregation hotspot region #1 (residues 242–252) showed a significant positive value and was mapped on to the homology model. However, overlapping peptides 3 to 7 covering residues 235–253 had positive, but statistically insignificant values were not mapped. In Figure 2, panel C, regions with weak increases in HX and strong increases in HX compared to HM-Fc are shown in cyan and dark blue, respectively. Regions with slower HX compared to HM-Fc are colored pink.

Figure 2:

Effects of glycan truncation on the average HX kinetics of the IgG1-Fc for all peptides relative to the high mannose IgG1-Fc glycoform. A) Regions of interest are mapped onto a homology model of the IgG1-Fc. B) HX kinetics of Man5-Fc (blue), GlcNAc-Fc (green), and N297Q-Fc (red) with respect to HM-Fc. represents the average of the deuterium differences at all HX times, normalized for peptide length and corrected for back-exchange, as defined by equation (3). The dashed lines represent the threshold for statistical significance as detailed in the Supporting Information. The arrows indicate the regions of interest. The peptides are indexed along the horizontal axis in order from N- to C-terminus as indicated in Supporting Table S1. C) Regions with statistically significant are shown mapped onto a homology model. Strong deprotection is shown as dark blue, moderate de-protection as cyan, and protection as pink compared to the high mannose glycoform. The homology model is based on PDB 1HZH.40

Summary of HX kinetics:

Nearly all of the significant changes in HX are positive relative to HM-Fc as shown in Figure 2, panel B. Hence, in these regions, each of the other glycoforms exchange faster than HM-Fc indicating that there is an increase in backbone flexibility with truncation of glycans from high mannose. However, peptide 12 (HC residues: 262–277) of Man5-Fc shows a negative value that indicates a decrease in backbone flexibility in this region relative to HM-Fc. As the glycan is progressively trimmed from Man5-Fc to GlcNAc-Fc to N27Q-Fc, both the number of regions affected and the magnitude of the effects increase, as shown in Figure 2B. Hence, IgG1-Fc backbone flexibility in these regions is inversely correlated with the size of N-glycans and increases in the following order HM-Fc < Man5-Fc < GlcNAc-Fc < N297Q-Fc. Peptide 12 in Man5-Fc is an exception, where slower exchange occurs and backbone flexibility decreases relative to HM-Fc (see Discussion section).

Mapping of regions with significant changes in HX:

The regions of significant changes (in Figure 2, panel B) were then mapped onto a homology model, as shown in Figure 2 C. Decreasing the glycan size from high mannose down to Man5 causes a weak increase in HX rates in a few regions located in CH2 and CH3 domains (colored in cyan). Most of the effects are localized in the CH2 domain, but there are also some increases in HX rates in the CH3 domain. Decreasing the glycan size from high mannose down to GlcNAc causes significant increases in backbone flexibility in the entire CH2 domain with effects much stronger than those observed in Man5. In the CH3 domain, the locations of the effects are similar to Man5, but the magnitude is slightly larger. The largest increases in HX followed de-glycosylation, where the entire IgG1-Fc becomes more flexible as compared to HM-Fc. Thus, overall, the degree of increase in HX and backbone flexibility was inversely dependent on the length of N-glycans and the effects were greater in the CH2 than in the CH3 domains.

Correlation of HX results with regions of interest:

Several regions of interest in the CH2 domain (see Discussion section), including two aggregation hotspots, an asparagine deamidation-prone region, and the C’E loop region (important for receptor binding and containing the N-linked N297 glycosylation site), are marked on the IgG1-Fc homology model in Figure 2 A and by arrows in Figure 2 B. Although there are significant HX differences in the glycopeptides (1718, blue arrow in Figure 2, panel B), the comparison of HX in glycopeptides is prone to potential HX artifacts (as described in the “HX kinetics” section), and so these results will not be interpreted further here. Changing the glycan sequentially from HM to Man5 to GlcNAc to non-glycosylated causes substantial increases in the rate of HX indicating increases in backbone flexibility in the deamidation prone regions (yellow arrows in figure 2, B pointing at peptides 24 and 25) and both the aggregation hotspots (magenta and red arrows in Figure 2, B pointing at peptides 3–8 and 20–23, respectively). However, shortening the glycan from HM to Man5 does not significantly alter HX in aggregation hotspot #2 (peptides 20–23). In a peptide in the CH2 domain containing an oxidation-prone tryptophan, W27717 (peptide 12, 262–277), there is a decrease in flexibility when the glycan is shortened from high mannose to Man5, but then an increase in flexibility with further glycan truncation.

Discussion

The goal of this work was to examine the effect of glycan size on the backbone flexibility of a series of well-defined IgG1-Fc glycoforms and to correlate these results with preceding work that correlated glycan size with chemical stability, conformational stability, aggregation propensity, and FcγRIIIa receptor in vitro binding activity.16–18 The hydrogen exchange results in this work revealed a trend of increasing backbone flexibility with decreasing N-glycan size (relative to high mannose) in the IgG1-Fc molecules. Decreasing the glycan size to Man5 caused the smallest increase in backbone flexibility, mostly in the CH2 domain and some regions of CH3. Further decreasing the glycan to a single GlcNAc at both N297 sites caused more widespread and larger increases in backbone flexibility as compared to Man5-Fc. Finally, removal of all glycans (N297Q-Fc) caused the largest increase in backbone flexibility across the entire IgG1-Fc molecule. The differences in flexibility were more prominent in the CH2 domain, but flexibility differences in some regions of the CH3 domains were also observed.

The overall physical stability, chemical stability, and receptor binding profiles of these four IgG1-Fc glycoforms were correlated with oligosaccharide structure in previously published series of papers.16–18 Previous differential scanning calorimetry, intrinsic and extrinsic fluorescence, and turbidity results16 showed that HM-Fc and Man5-Fc were the most stable, GlcNAc-Fc was intermediate, and N297Q-Fc was the least stable. Also, the apparent solubility of these IgG1-Fc glycoforms, measured by PEG precipitation assay, decreased as the glycans were sequentially truncated from HM to non-glycosylated N297Q.16 As measured by a turbidity assay (a thermal ramp from 10°C to 90°C at a rate of 60°C/h), the aggregation propensities of GlcNAc-Fc and the aglycosylated N297Q-Fc were greater than that observed for the HM-Fc and Man5-Fc (proteins containing the larger oligosaccharide structures).16 Additionally, Okbazghi et al18 showed that HM-Fc and Man5-Fc both had similar high affinities for FcγRIIIa, while GlcNAc-Fc had lower affinity, and the non-glycosylated N297Q-Fc had no measurable affinity for FcγRIIIa. Glycosylation also affected chemical stability of these glycoproteins as previously described by Mozziconacci et al.17 HM-Fc and Man5-Fc were more susceptible to tryptophan oxidation at W277 but less susceptible to deamidation at N315 than GlcNAc and non-glycosylated N297Q-IgG1-Fc. It is important to see the overall flexibility results of the various IgG1-Fc glycoforms in the light of conformational and chemical stability, aggregation propensity, and receptor binding of mAbs. In general, these comparisons provide further insight into their pharmaceutical development as discussed below.

Correlations between aggregation propensity, HX, and glycosylation

Under given solution conditions, the rate and extent of protein aggregation observed across these well-defined IgG1-Fc glycoforms can be affected by a variety of factors such as protein structure/post translational modifications, conformational integrity, protein-protein interactions and environmental stress conditions (pH, ionic strength, temperature, light, etc.).45 Understanding the inter-relationships between protein’s structure, conformational integrity, colloidal stability and local flexibility will help in better understanding of protein aggregation to facilitate pharmaceutical development of mAbs. Various hydrophobic, aggregation-prone sites have been identified in both the variable and constant regions of IgG antibodies by in silico and HX-MS analysis.46,47 Previous HX-MS studies have found that a particular segment near the F243 (residues 241–252, FLFPPKPKDTLM; peptides 3–8 in this study) in the CH2 domain of the Fc became more flexible in response to destabilizing additives (e.g., thiocyanate, arginine, and anti-microbial agents), methionine oxidation, N297 deglycosylation, and introduction of point mutations.28–31,47,48 Thus, this segment appears to be a common point-of-failure under a wide variety of aggregation-promoting conditions. Previously, two separate studies from our laboratories proposed that this region is an aggregation hotspot in mAbs (referred to as aggregation hotspot # 1 in this study, see Figure 2, panel A, magenta colored region).29,30 Here, we find that decreasing the glycan size substantially increases backbone flexibility in aggregation hotspot #1.

Additionally, we observed increases in backbone flexibility as glycan size decreased in a second region spanning HC residues 300–306 (YRVVSVL, peptides 20–23) of the CH2 domain. This result is consistent with previously observed increases in flexibility of this region of a different IgG1 mAb in presence of aggregation-promoting thiocyanate.29 This particular region exchanges quite slowly, so that differences only become apparent after long HX times (see Figure 1). Increases in backbone flexibility, measured by HX-MS, in residues 273–306 upon substitution of complex glycans with high-mannose glycans in an IgG2 antibody15 and upon Y407 mutation in the CH3 domain of an IgG1 mAb49 have also been reported. Previous studies based on various computational approaches have also identified this hydrophobic region in mAbs as aggregation-promoting.50 Here, we denote this second region as aggregation hotspot # 2 (peptides 20–23, see Figure 2, panel A, red colored region). In aggregation hotspot #2, compared to HM, flexibility was greatest in the deglycosylated form (N297Q mutation), intermediate in the GlcNAc-Fc form, and unchanged in Man5-Fc.

The extent of change in the backbone flexibility near these two aggregation hotspots, conformational instability, and increased aggregation propensity of IgG1-Fc glycoforms all correlate well with the decreased size of the glycan. In previous work,16 we found that under thermal stress, both the non-glycosylated N297Q-Fc and GlcNAc-Fc aggregated at the same onset temperature, but that the propensity of N297Q-Fc aggregation was higher than GlcNAc-Fc based on the rate and extent of turbidity formation. In this same assay, HM-Fc and Man5-Fc glycoforms did not aggregate. Elucidation of the mechanism(s) of aggregate formation was not a focus of this study with the various IgG1-Fc glycoforms due to limited material availability. Thus, turbidity formation provided a rapid overall assessment of aggregation propensity, but such measurements cannot distinguish between the amounts vs. size of aggregates formed. However, in related work in our laboratory, good correlations of enhanced local flexibility in the aggregation hot spot #1 (as measured by HX) with elevated levels of soluble aggregate and subvisible particle formation, as measured by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) and Microflow imaging (MFI) respectively, during thermal stress of a full length IgG4 mAb has been demonstrated.51

We speculate that the exposure of hydrophobic residues in CH2 domain increases aggregation propensity of IgG1-Fc. In X-ray crystal structures of mAbs and Fc domains, residues F241, F243, K246, in aggregation hotspot #1, and R301, in aggregation hotspot #2, have been shown to interact with the glycans through hydrogen bonds or hydrophobic interactions;40,52–55 most of these interactions would probably be lost in the GlcNAc and non-glycosylated CH2 forms of these IgG1-Fc proteins leading to increased backbone flexibility.

Correlations between chemical stability, HX, and glycosylation

In previous work, deamidation of N315 in HM-Fc, Man5-Fc, GlcNAc-Fc and N297Q-Fc was followed during a three month accelerated stability study at 40°C.17 The rate of deamidation of N315 was faster for GlcNAc-Fc and N297Q-Fc than for HM-Fc and Man5-Fc, indicating that trimming or removing the N-glycan promotes deamidation of N315.17 A direct correlation between the rate of N315 deamidation and the backbone flexibility of peptides (24 and 25) containing the N315 was observed with the four IgG1-Fc glycoforms. Backbone flexibility of the CH2 domain in peptides 24 and 25 (containing N315) significantly increased as the size of glycan was truncated from HM-Fc, to Man5-Fc, GlcNAc-Fc and non-glycosylated N297Q-Fc (see Figure 1 for uptake plot of peptide 24, and Figure 2 for average difference plots of peptides 24 and 25). Previous studies have reported deamidation of N315 in IgG mAbs, both in vivo and in vitro, and attributed this result to changes in flexibility in the N315 region.56–60 We are also examining this intriguing correlation in greater detail elsewhere (Gamage and Weis, manuscript in preparation). The correlation of enhanced deamidation at N315 with increased local flexibility in IgG1-Fc protein in the peptide segments containing N315 observed by HX, as function of glycoform structure, is consistent with the known mechanism of Asn deamidation in proteins via a succinimide intermediate involving the polypeptide backbone (where increase in flexibility of the polypeptide backbone increases the rate of succinimide intermediate formation followed by hydrolysis to isoAsp/Asp residues).61

The same accelerated stability study revealed that the rate of oxidative degradation of W277 to glycine hydroperoxide also depended on the degree of glycosylation.17 In this case, however, conversion was faster in the HM-Fc and Man5-Fc than in GlcNAc-Fc and non-glycosylated N297Q-Fc, indicating that a decrease in size of the N-glycan decreases the degradation of W277.17 In this HX study, we observed that peptide 12 (262–277) containing W277 in the CH2 domain showed the greatest flexibility in N297Q-Fc (see Figure 1 and 2), intermediate flexibility in GlcNAc-Fc, and the least flexibility in HM-Fc and Man5-Fc. In fact, Man5-Fc showed slightly lower flexibility in this peptide than HM-Fc (less HX at 104 s and 105 s, see in Figure 1). Other overlapping peptides containing W277 (peptides 13, 14 and 15) all manifested similar overall trends in flexibility with the size of glycans as seen in peptide 12, but the differences were not significantly significant for Man-Fc (see Figure 2). Our results indicate that as the glycans were sequentially truncated, the flexibility in peptide 12 increased significantly. Thus, the rate of W277 oxidation appears to be inversely correlated with backbone flexibility and directly correlated with glycan size. However, at this point we cannot explain how the glycan structure affects W277 oxidation to Gly hydroperoxide. However, the inverse-correlation with backbone flexibility suggests that the reaction might involve a critical intramolecular contact that is progressively disrupted as the backbone flexibility increases.

Developing a better understanding of the inter-relationships of perturbations in local dynamics due to changes in glycan structure and susceptibility of physicochemical degradation remains a long term goal. For example, the link between protein flexibility and Asn deamidation is well established and results of this work are consistent with the mechanism of succinimide formation.62 However, correlations between protein flexibility and protein stability are more complex with conflicting observations in the literature.62 As shown in this work, local flexibility effects due to oligosaccharide structures (such as observed in aggregation hot spots #1 and #2 in the CH2 domain of the IgG1-Fc glycoforms) appear to be an indicator of physical instability (such as aggregation). The mechanism(s) of sequential sugar residue truncation on the enhancement of N315 deamidation and protein aggregation in the IgG1-Fc remain to be fully elucidated as part of future work, but likely includes changes in interactions between the side chain sugars residues and the protein’s polypeptide backbone (resulting in increased distal flexibility of the polypeptide chain).

Correlations between Fc receptor binding, HX, and glycosylation

A number of studies report the effects of carbohydrate composition on binding affinity of mAbs with various Fcγ receptors.63 The Fc receptor FcγRIIIa is the primary target for most therapeutic mAbs that require ADCC action and FcγRIIIa-Fc is the most studied interaction.13,63 Studies using X-ray crystallography and Fc engineering have identified different regions in the lower hinge and CH2 domain that are essential to maintain interactions with FcγRIIIa receptors.32,64 However, the role of N-glycans in modulating this interaction remains unclear. One hypothesis is that the glycan maintains the overall CH2 domain orientation of the Fc for its interaction with FcγRIIIa.65,66 An alternative hypothesis is that the glycans affect the dynamics of the C’E loop (residues 295–300) and that the loop dynamics modulate receptor binding.67,68 In previously described Fc receptor in vitro binding studies with these four Fc glycoforms, HM-Fc and Man5-Fc displayed the highest affinities for FcγRIIIa, GlcNAc-Fc had lower affinity, and N297Q-Fc did not show any binding to the receptor.18 Additionally, recent molecular dynamics simulations of the four IgG1-Fc glycoforms have shown that the N-glycan composition affects the dynamics of the C’E loop and the CH2-CH3 orientation.69 These results suggest that decreased conformational sampling in Man8 and Man5 glycoforms is responsible for more efficient binding to the FcγRIIIa receptor.

In this work, we found an inverse correlation between HX rate and glycan length in peptides known to be important for receptor binding: peptides 17–19 (which include C’E loop and N-glycans), peptides 3–4 (containing residues 235–239), peptides 5–8 (containing 241–246; aggregation hotspot #1 in our study),68 peptides 12–15 (containing residues 265–269), and peptides 26–27 (containing residues 327–332). We observed that, relative to HM, Man5-Fc had the smallest increase in HX, GlcNAc-Fc had an intermediate increase, while the N297Q-Fc had the greatest increase in HX in all these peptides. However, HX was faster in Man5-Fc than in HM-Fc in the C’E loop peptides 17–18 (see Supporting Information; Supplemental Figure S1) and peptides 26–27 (see Figure 2). Additionally, we observed significant increases in HX each of the glycoforms in peptide 16 (residues: 278–293) which lies just before the C’E loop, which could be important for FcγRIIIa binding as suggested in an HX-MS study on fucose depleted complex glycoforms in the presence of FcγRIIIa (residues 279–301).32 Again, quantitative trends in HX in peptides 17–18 (containing the N-linked glycans) should be compared with caution due to the potential artifacts in measuring HX in glycopeptides, as noted in the Results section.

Overall, these results point towards complex correlations between IgG-Fc conformational integrity, backbone flexibility, and strength of interaction with the FcγRIIIa receptors that are modulated by oligosaccharide size. Overall, these HX-MS results seem to favor the hypothesis that glycosylation modulates the Fc structure leading to altered receptor binding since we see nearly global increases in HX as the glycan is progressively diminished. However, these effects do include increased dynamics within the C’E loop. Future work in better understanding the mechanism of the receptor binding by N-glycan modulation in the context of local flexibility measurements of well-defined IgG glycoforms could provide opportunities for improved IgG therapeutics.

Comparisons of IgG-Fc glycoform HX-MS results with previously reported HX-MS analysis of the effects of glycosylation on full-length antibodies

The effects of converting the glycans of intact monoclonal antibodies from the complex to deglycosylated forms by PNGase-F treatment has been investigated in a few previous HX-MS studies, but the results are contradictory. 31–33 Houde et al.31 reported both increased and decreased HX rates within isolated segments of the CH2 and CH3 domains of an IgG1 upon complete removal of complex glycans, but in subsequent work32, only faster HX within the aggregation hotspot #1 region was observed. In contrast, when an IgG2 was converted from complex glycan to high-mannose and hybrid glycans, there was widespread increase in HX throughout the CH2 and CH3 domains, with the largest effects within aggregation hotspot #1.15 Conversion of trastuzumab from complex glycan to deglycosylated form had almost no effect on HX when measured using a middle-down HX-MS approach, except for the region near residues L317 and N318 became more flexible upon glycan removal.33 Our results with these well-defined IgG1-Fc glycoforms appear to be most consistent with the results observed within the aggregation hotspot #1 from the studies of Fang et al15 and Houde et al.31 Despite the contradictions in observations across these studies, the substantially increased HX within the aggregation hotspot #1 region is noteworthy.

Conclusions

In this work, we demonstrate that sequentially decreasing the glycan size (from high mannose (Man8-Man12) to Man5, to GlcNAc, to non-glycosylated) increased the backbone flexibility of IgG1-Fc molecules. These HX-MS results with four well-defined IgG1-Fc glycoforms were correlated with the chemical stability, physical stability and FcγRIIIa receptor in vitro binding results previously described.16–18 Our HX-MS results suggest that the mechanism of deamidation of N315, increased aggregation propensity, and reduced receptor binding involve increased backbone flexibility caused by diminished stabilizing interactions between glycans and residues in the CH2 domain as the glycans are sequentially truncated. Hence, the HX-MS approach applied to the IgG1-Fc glycoforms in this work demonstrates the sensitivity of HX-MS measurements to detect subtle effects caused by altered glycosylation on the Fc backbone. The HX-MS measurements can enable a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms that contribute to pharmaceutical properties including physicochemical stability and receptor binding. Using IgG1-Fc glycoforms as a model system, we thus demonstrate that HX measurements of local flexibility differences can provide discriminating structural insights into the varying pharmaceutical properties of IgG glycoforms. Such HX data sets may therefore prove to be an important component of future comparability and/or biosimilarity assessments of therapeutic glycoprotein candidates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was made possible, in part, by the Food and Drug Administration through grant 1U01FD005285–01; views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services nor does any mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organization imply endorsement by the United States government. The authors wish to also acknowledge financial support of TJT via NIH grant NIGMS R01 GM090080 and SZO via NIH biotechnology training grant 5-T32-GM008359. An equipment loan from Agilent Technologies is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang X, Wang Y 2016. Glycosylation Quality Control by the Golgi Structure. J Mol Biol 428(16):3183–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh G, Jefferis R 2006. Post-translational modifications in the context of therapeutic proteins. Nat Biotechnolnol 24(10):1241–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh G 2014. Biopharmaceutical benchmarks 2014. Nat Biotechnol 32(10):992–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volkin DB, Hershenson S, Ho RJY, Uchiyama S, Winter G, Carpenter JF 2015. Two Decades of Publishing Excellence in Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. J Pharm Sci 104(2):290–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelman GM, Cunningham BA, Gall WE, Gottlieb PD, Rutishauser U, Waxdal MJ 1969. The covalent structure of an entire gammaG immunoglobulin molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 63(1):78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abhinandan KR, Martin AC 2008. Analysis and improvements to Kabat and structurally correct numbering of antibody variable domains. Mol Immunol 45(14):3832–3839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vidarsson G, Dekkers G, Rispens T 2014. IgG subclasses and allotypes: from structure to effector functions. Front Immunol 5:520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Béranger S, Martinez-Jean C., Bellahcene F, Lefranc M-P. 2001. Correspondence between the IMGT unique numbering for C-DOMAIN, the IMGT exon numbering, the Eu and Kabat numberings: Human IGHG. Available at: http://www.imgt.org/IMGTScientificChart/Numbering/Hu IGHGnber.html. Accessed Oct, 25 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irani V, Guy AJ, Andrew D, Beeson JG, Ramsland PA, Richards JS 2015. Molecular properties of human IgG subclasses and their implications for designing therapeutic monoclonal antibodies against infectious diseases. Mol Immunol 67(2 Pt A):171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quast I, Peschke B, Lunemann JD 2017. Regulation of antibody effector functions through IgG Fc N-glycosylation. Cell Mol Life Sci 74(5):837–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen PF, Larraillet V, Schlothauer T, Kettenberger H, Hilger M, Rand KD 2015. Investigating the interaction between the neonatal Fc receptor and monoclonal antibody variants by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics 14(1):148–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huhn C, Selman MH, Ruhaak LR, Deelder AM, Wuhrer M 2009. IgG glycosylation analysis. Proteomics 9(4):882–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu L 2015. Antibody Glycosylation and Its Impact on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Monoclonal Antibodies and Fc-Fusion Proteins. J Pharm Sci 104(6):1866–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reusch D, Tejada ML 2015. Fc glycans of therapeutic antibodies as critical quality attributes. Glycobiology 25(12):1325–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang J, Richardson J, Du Z, Zhang Z 2016. Effect of Fc-Glycan Structure on the Conformational Stability of IgG Revealed by Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange and Limited Proteolysis. Biochemistry 55(6):860–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.More AS, Toprani VM, Okbazghi SZ, Kim JH, Joshi SB, Middaugh CR, Tolbert TJ, Volkin DB 2016. Correlating the Impact of Well-Defined Oligosaccharide Structures on Physical Stability Profiles of IgG1-Fc Glycoforms. J Pharm Sci 105(2):588–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mozziconacci O, Okbazghi S, More AS, Volkin DB, Tolbert T, Schoneich C 2016. Comparative Evaluation of the Chemical Stability of 4 Well-Defined Immunoglobulin G1-Fc Glycoforms. J Pharm Sci 105(2):575–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okbazghi SZ, More AS, White DR, Duan S, Shah IS, Joshi SB, Middaugh CR, Volkin DB, Tolbert TJ 2016. Production, Characterization, and Biological Evaluation of Well-Defined IgG1 Fc Glycoforms as a Model System for Biosimilarity Analysis. J Pharm Sci 105(2):559–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li F, Vijayasankaran N, Shen A, Kiss R, Amanullah A 2010. Cell culture processes for monoclonal antibody production. MAbs 2(5):466–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi HH, Goudar CT 2014. Recent advances in the understanding of biological implications and modulation methodologies of monoclonal antibody N-linked high mannose glycans. Biotechnol Bioeng 111(10):1907–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Q, Shankara S, Roy A, Qiu H, Estes S, McVie-Wylie A, Culm-Merdek K, Park A, Pan C, Edmunds T 2008. Development of a simple and rapid method for producing non-fucosylated oligomannose containing antibodies with increased effector function. Biotechnol Bioeng 99(3):652–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flynn GC, Chen X, Liu YD, Shah B, Zhang Z 2010. Naturally occurring glycan forms of human immunoglobulins G1 and G2. Mol Immunol 47(11):2074–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goetze AM, Liu YD, Zhang Z, Shah B, Lee E, Bondarenko PV, Flynn GC 2011. High-mannose glycans on the Fc region of therapeutic IgG antibodies increase serum clearance in humans. Glycobiology 21(7):949–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang W, Singh SK, Li N, Toler MR, King KR, Nema S 2012. Immunogenicity of protein aggregates—Concerns and realities. Int J Pharm 431(1–2):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alsenaidy MA, Jain NK, Kim JH, Middaugh CR, Volkin DB 2014. Protein comparability assessments and potential applicability of high throughput biophysical methods and data visualization tools to compare physical stability profiles. Front Pharmacol 5:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JH, Joshi SB, Tolbert TJ, Middaugh CR, Volkin DB, Smalter Hall A 2016. Biosimilarity Assessments of Model IgG1-Fc Glycoforms Using a Machine Learning Approach. J Pharm Sci 105(2):602–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arora J, Hu Y, Esfandiary R, Sathish HA, Bishop SM, Joshi SB, Middaugh CR, Volkin DB, Weis DD 2016. Charge-mediated Fab-Fc interactions in an IgG1 antibody induce reversible self-association, cluster formation, and elevated viscosity. MAbs 8(8):1561–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Majumdar R, Esfandiary R, Bishop SM, Samra HS, Middaugh CR, Volkin DB, Weis DD 2015. Correlations between changes in conformational dynamics and physical stability in a mutant IgG1 mAb engineered for extended serum half-life. MAbs 7(1):84–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Majumdar R, Manikwar P, Hickey JM, Samra HS, Sathish HA, Bishop SM, Middaugh CR, Volkin DB, Weis DD 2013. Effects of salts from the Hofmeister series on the conformational stability, aggregation propensity, and local flexibility of an IgG1 monoclonal antibody. Biochemistry 52(19):3376–3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manikwar P, Majumdar R, Hickey JM, Thakkar SV, Samra HS, Sathish HA, Bishop SM, Middaugh CR, Weis DD, Volkin DB 2013. Correlating excipient effects on conformational and storage stability of an IgG1 monoclonal antibody with local dynamics as measured by hydrogen/deuterium-exchange mass spectrometry. J Pharm Sci 102(7):2136–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houde D, Arndt J, Domeier W, Berkowitz S, Engen JR 2009. Characterization of IgG1 Conformation and Conformational Dynamics by Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem 81(7):2644–2651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houde D, Peng Y, Berkowitz SA, Engen JR 2010. Post-translational modifications differentially affect IgG1 conformation and receptor binding. Mol Cell Proteomics 9(8):1716–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan J, Zhang S, Chou A, Borchers CH 2016. Higher-order structural interrogation of antibodies using middle-down hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Chem Sci 7(2):1480–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasoe PK, Long FA 1960. Use Of Glass Electrodes To Measure Acidities In Deuterium Oxide1,2. J Phys Chem 64(1):188–190. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toth RT, Mills BJ, Joshi SB, Esfandiary R, Bishop SM, Middaugh CR, Volkin DB, Weis DD 2017. Empirical Correction for Differences in Chemical Exchange Rates in Hydrogen Exchange-Mass Spectrometry Measurements. Anal Chem 89(17):8931–8941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Busby SA, Chalmers MJ, Griffin PR 2007. Improving digestion efficiency under H/D exchange conditions with activated pepsinogen coupled columns. Int J Mass Spectrom 259(1):130–139. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majumdar R, Manikwar P, Hickey JM, Arora J, Middaugh CR, Volkin DB, Weis DD 2012. Minimizing carry-over in an online pepsin digestion system used for the H/D exchange mass spectrometric analysis of an IgG1 monoclonal antibody. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 23(12):2140–2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mechref Y 2012. Use of CID/ETD mass spectrometry to analyze glycopeptides. Curr Protoc Protein Sci Chapter 12:Unit 121111–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinneburg H, Stavenhagen K, Schweiger-Hufnagel U, Pengelley S, Jabs W, Seeberger PH, Silva DV, Wuhrer M, Kolarich D 2016. The Art of Destruction: Optimizing Collision Energies in Quadrupole-Time of Flight (Q-TOF) Instruments for Glycopeptide-Based Glycoproteomics. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 27(3):507–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saphire EO, Parren PW, Pantophlet R, Zwick MB, Morris GM, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Stanfield RL, Burton DR, Wilson IA 2001. Crystal structure of a neutralizing human IGG against HIV-1: a template for vaccine design. Science 293(5532):1155–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guttman M, Scian M, Lee KK 2011. Tracking hydrogen/deuterium exchange at glycan sites in glycoproteins by mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 83(19):7492–7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Z, Zhang A, Xiao G 2012. Improved protein hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry platform with fully automated data processing. Anal Chem 84(11):4942–4949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsumiya S, Yamaguchi Y, Saito J, Nagano M, Sasakawa H, Otaki S, Satoh M, Shitara K, Kato K 2007. Structural comparison of fucosylated and nonfucosylated Fc fragments of human immunoglobulin G1. J Mol Biol 368(3):767–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sondermann P, Huber R, Oosthuizen V, Jacob U 2000. The 3.2-A crystal structure of the human IgG1 Fc fragment-Fc gammaRIII complex. Nature 406(6793):267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu H, Kroe-Barrett R, Singh S, Robinson AS, Roberts CJ 2014. Competing aggregation pathways for monoclonal antibodies. FEBS Lett 588(6):936–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chennamsetty N, Helk B, Voynov V, Kayser V, Trout BL 2009. Aggregation-prone motifs in human immunoglobulin G. J Mol Biol 391(2):404–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Majumdar R, Middaugh CR, Weis DD, Volkin DB 2015. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry as an emerging analytical tool for stabilization and formulation development of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. J Pharm Sci 104(2):327–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arora J, Joshi SB, Middaugh CR, Weis DD, Volkin DB 2017. Correlating the Effects of Antimicrobial Preservatives on Conformational Stability, Aggregation Propensity, and Backbone Flexibility of an IgG1 mAb. J Pharm Sci 106(6):1508–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rose RJ, van Berkel PHC, van den Bremer ETJ, Labrijn AF, Vink T, Schuurman J, Heck AJR, Parren PWHI 2013. Mutation of Y407 in the CH3 domain dramatically alters glycosylation and structure of human IgG. MAbs 5(2):219–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang X, Das TK, Singh SK, Kumar S 2009. Potential aggregation prone regions in biotherapeutics: A survey of commercial monoclonal antibodies. MAbs 1(3):254–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toth RT, Pace SE, Mills BJ, Joshi SB, Esfandiary R, Middaugh CR, Weis DD, Volkin DB 2018. Evaluation of Hydrogen Exchange Mass Spectrometry as a Stability-Indicating Method for Formulation Excipient Screening for an IgG4 Monoclonal Antibody. J Pharm Sci 107(4):1009–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lu J, Chu J, Zou Z, Hamacher NB, Rixon MW, Sun PD 2015. Structure of FcgammaRI in complex with Fc reveals the importance of glycan recognition for high-affinity IgG binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112(3):833–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Matsumiya S, Yamaguchi Y, Saito J-i, Nagano M, Sasakawa H, Otaki S, Satoh M, Shitara K, Kato K. 2007. Structural Comparison of Fucosylated and Nonfucosylated Fc Fragments of Human Immunoglobulin G1. ed. p 767–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nagae M, Yamaguchi Y 2012. Function and 3D structure of the N-glycans on glycoproteins. Int J Mol Sci 13(7):8398–8429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shah IS, Lovell S, Mehzabeen N, Battaile KP, Tolbert TJ 2017. Structural characterization of the Man5 glycoform of human IgG3 Fc. Mol Immunol 92:28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu YD, van Enk JZ, Flynn GC 2009. Human antibody Fc deamidation in vivo. Biologicals 37(5):313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang L, Amphlett G, Lambert JM, Blattler W, Zhang W 2005. Structural characterization of a recombinant monoclonal antibody by electrospray time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Pharm Res 22(8):1338–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sinha S, Zhang L, Duan S, Williams TD, Vlasak J, Ionescu R, Topp EM 2009. Effect of protein structure on deamidation rate in the Fc fragment of an IgG1 monoclonal antibody. Protein Sci 18(8):1573–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chelius D, Rehder DS, Bondarenko PV 2005. Identification and characterization of deamidation sites in the conserved regions of human immunoglobulin gamma antibodies. Anal Chem 77(18):6004–6011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Phillips JJ, Buchanan A, Andrews J, Chodorge M, Sridharan S, Mitchell L, Burmeister N, Kippen AD, Vaughan TJ, Higazi DR, Lowe D 2017. Rate of Asparagine Deamidation in a Monoclonal Antibody Correlating with Hydrogen Exchange Rate at Adjacent Downstream Residues. Anal Chem 89(4):2361–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wakankar AA, Borchardt RT 2006. Formulation considerations for proteins susceptible to asparagine deamidation and aspartate isomerization. J Pharm Sci 95(11):2321–2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamerzell TJ, Middaugh CR 2008. The complex inter-relationships between protein flexibility and stability. J Pharm Sci 97(9):3494–3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hanson QM, Barb AW 2015. A perspective on the structure and receptor binding properties of immunoglobulin G Fc. Biochemistry 54(19):2931–2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Subedi GP, Barb AW 2016. The immunoglobulin G1 N-glycan composition affects binding to each low affinity Fc gamma receptor. MAbs 8(8):1512–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krapp S, Mimura Y, Jefferis R, Huber R, Sondermann P 2003. Structural Analysis of Human IgG-Fc Glycoforms Reveals a Correlation Between Glycosylation and Structural Integrity. J Mol Biol 325(5):979–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mimura Y, Church S, Ghirlando R, Ashton PR, Dong S, Goodall M, Lund J, Jefferis R 2000. The influence of glycosylation on the thermal stability and effector function expression of human IgG1-Fc: properties of a series of truncated glycoforms. Mol Immunol 37:697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Subedi GP, Barb AW 2015. The Structural Role of Antibody N-Glycosylation in Receptor Interactions. Structure 23(9):1573–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Subedi GP, Hanson QM, Barb AW 2014. Restricted motion of the conserved immunoglobulin G1 N-glycan is essential for efficient FcgammaRIIIa binding. Structure 22(10):1478–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee HS, Im W 2017. Effects of N-Glycan Composition on Structure and Dynamics of IgG1 Fc and Their Implications for Antibody Engineering. Scientific Reports 7(1):12659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.