Abstract

Objectives.

Latinos have a disproportionately high risk for obesity and hypertension. The current study analyzes survey data from Latin American women to detect differences in rates of obesity and hypertension based on their number of health-related social ties. Additionally, it proposes individuals’ health-related media preference (ethnic/ mainstream) as a potential moderator.

Design.

The dataset includes 364 Latinas (21 to 50 years old) from the greater Los Angeles metropolitan area, who responded to a series of sociodemographic, physiological, health-related, and media-related questions.

Results.

Controlling for various sociodemographic and health variables, each additional health-related tie in a Latina’s social network significantly decreased her likelihood of being obese OR = .79, p = .041, 95% CI [.66, .95], but did not affect hypertension. Further, the analysis revealed a significant interaction between media preference and health-related social ties, such that exposure to ethnic media tended to compensate for the absence of social ties for the likelihood of obesity OR = .75, p = .041, 95% CI [.52, .97], as well as hypertension OR = .79, p = .045, 95% CI [.55, .98].

Conclusion.

In concurrence with the literature, increases in health-related ties reduced the likelihood of obesity in this population. Moreover, ethnic media preference may play an important role in mitigating the likelihood of obesity and hypertension among Latinas.

Keywords: Latinas, obesity, body mass index, hypertension, social networks, ethnic media, mainstream media, socioeconomic status, health behaviors

Introduction

In recent years, the idea that insufficient access to health information, in and of itself, poses a serious health concern has gained momentum, as evidenced in the growing numbers of studies that treat lack of access to information as a risk factor and a predictor of health disparities (Kelley, Su, and Britigan 2016; Nguyen, Shiu, and Peters 2015). Indeed, the ability to obtain accurate information quickly and conveniently increases informed decision-making and participation in care (Berland et al. 2001). Generally speaking, findings show that lack of access to health information can lead to a wide range of negative mental, emotional, and physical outcomes (Flores et al. 2016; Kontos et al. 2014). Nationally, obesity is an enormously costly health crisis, and rates of obesity are on the rise in Latino populations in particular (CDC 2015a).

Another major risk factor for disease among Hispanics is associated with Hypertension, the medical term for high blood pressure. According to the American Heart Association (2016), Latinos face higher risks of heart disease, compared to US non-Hispanic Whites, because of high blood pressure, increasing rates of obesity, and the prevalence of diabetes. As with obesity, maintaining a healthy diet and engaging in regular physical activity are particularly effective ways to reduce the likelihood of hypertension (Kell et al. 2014; Sorlie et al. 2014). Likewise, better access to health-related information and increase in awareness regarding hypertension are associated with a substantial decrease in the percentage of uncontrolled hypertension among adults (Khatib et al. 2014). Nonetheless, there are still considerable racial/ethnic disparities with higher percentage of undiagnosed and uncontrolled cases of hypertension among Mexican Americans (Cutler et al. 2008; Yoon et al. 2014). Given that Latinos are the fastest growing population in the United States – it is estimated that one in three children will be Latino by 2030 – it is critically important to address these disparities (State of Obesity 2014).

One way shown to combat the ill effects of insufficient access to health information is associated with the creation and maintenance of social ties with other individuals, (i.e., the formation and upkeep of a social network and the utilization of the interpersonal resources it affords) (Portes and Vickstrom 2011). An increase in the number of social ties an individual possesses could decrease the likelihood of obesity and hypertension in at least two ways. First, considering that loneliness is highly associated with obesity (Pettite et al. 2015), an increase in health-related social ties could decrease social isolation thus reducing the chances of obesity and hypertension. Second, expansion of personal connections could also enhance access to health-related information and increase health awareness (Aldrich 2012; Granovetter 1973), which ultimately could encourage individuals to seek opportunities for better care. As summarized by Valente (2012), increases in health network size and diversity may stimulate health information diffusion and thus have a positive impact on a wide range of health outcomes.

Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Health-related social ties will be a negative predictor of (a) obesity and (b) hypertension among Latinas, such that increase in the number of ties will reduce the likelihood of obesity and hypertension.

Ethnic Media and Health Literacy

Screen time is often linked with obesity and poor health through two mechanisms: promoting unhealthy eating habits and/or lack of exercise (Rosen et al. 2014). In particular, prolonged time with screens not only increases the likelihood that individuals would be exposed to the marketing of high in fat and sugar food but it also tends to inhibit physical activity and socialization with others. Thus, the key assumption that underlies much of the research that links media consumption with poor health is that excessive media use can cause - or at least be correlated with - health problems. That being said, the vast majority of research into the interplay between media, obesity, and hypertension focused, almost exclusively, on children and teens, with much less emphasis given to adults. In addition, the measurements of media consumption often do not provide a distinction between different types of media content, as they only measure hours of daily consumption (for example see Pardee et al. 2007). In fact, there are reasons to suspect that, under certain conditions and for some populations, media consumption can reduce health disparities.

Immigrant communities often depend on ethnic media to bridge cultural and lingual barriers (Matsaganis, Katz, and Ball-Rokeach 2010). According to the Communication Infrastructure Theory (CIT), ethnic media provides one of the major building blocks to structure and maintain civic communities with efficient networks of information (Wilkin et al. 2015). Namely, specific ethnic communities tend to have a shared background and identity that is more likely to be reflected in ethnic, rather than mainstream media (Kim and Ball-Rokeach 2006). In addition, ethnic media often differs from mainstream media by covering topics tailored to the needs and concerns of specific ethnic groups, in their primary language. Considering that limited English proficiency has been linked to a reduced number of visits to healthcare professionals (Derose and Baker 2000), language matters when it comes to health. In the Latino context, language has been identified as a major barrier to successful healthcare, especially among less-acculturated individuals (Sheppard et al. 2014).

Whereas mainstream media cover a wider range of interests and needs, ethnic media work to meet the communication needs and preferences of specific communities (Viswanath and Arora 2000). According to Kutner et al. (2006), easy access to health information is particularly important in Latino communities, where health literacy lags far behind every other major ethnic group in the United States. Given ethnic media’s specialized focus, it could serve as a ‘bridge’ in someone’s social network — connecting him or her to valuable resources that improve health outcomes. Thus, we hypothesize that among Latinas:

H2: Exposure to ethnic media will be a negative predictor of (a) obesity and (b) hypertension, such that compared to mainstream media, exposure to ethnic media will be associated with a reduced likelihood of obesity and hypertension.

Moreover, based on the role of ethnic media as a resource that can potentially compensate for the lack of health-related social ties, we also expect that:

H3: The relationship between health-related social ties (a) obesity, and (b) hypertension will be moderated by media preference, such that ethnic media will mitigate the effect of health-related social ties on obesity and hypertension among Latinas, as compared to mainstream media.

Methods

The data used for this study were collected as part of a National Cancer Institute grant that explored Latinas’ barriers to healthcare. The surveys were administered in clinics in the Los Angeles area and were conducted by researchers in either Spanish or English based on participants’ preferences from April 2012 to December 2013. After consenting to participate in the study, respondents answered a series of questions regarding their health-related social ties, healthcare, as well as sociodemographic variables. Following the survey, physiological measurements including weight, height, and blood pressure were taken by research assistants for each participant. We drew on data from the 364 respondents who had complete information on the survey items and had a reliably calculated Body Mass Index (BMI), as well as systolic and diastolic blood pressure. All participants were Latinas, 21 to 50 years old with a mean age of 35.07 (SD = 9.46).

Measures

Body Mass Index (BMI) and obesity

To gather information on the dependent variable, interviewers weighed participants and recorded their height during the interview; this information was used to calculate their BMI. To ensure reliability, all interviewers were trained by medical staff, and height and weight measures were repeated twice. After confirming that BMI was normally distributed as expected, in the interest of consistency with previous studies, the BMI measurement was divided into two categories: obese (30 and above) and not obese (below 30), the standards for which were based on those set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015b).

Blood pressure and hypertension

In order to record measurements of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, we used the Omron 3 series wrist blood pressure monitor, which took an average of three readings across 10 minutes. Analogous to height and weight, the procedure of blood pressure measurement was standardized, as all interviewers were trained by medical staff prior to conducting the interviews. After the blood pressure assessments were obtained, they were recoded into two categories to reflect the difference between hypertension (defined as systolic blood pressure [BP] ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg) and non-hypertension (American Heart Association 2017).

Health-related social network

To assess health-related social ties, the questionnaire asked respondents to list up to five people with whom they discuss issues related to health. The items also gathered follow-up information about each person a respondent would list, inquiring about the relationship role (e.g., mother, sister, friend) and their gender.

Ethnic and mainstream media use

Based on the Media System Dependency measurements (Ball-Rokeach 1998), information regarding media use was estimated by asking respondents to choose their most important sources of health-related information from a list that included, television, radio, newspapers, books, magazines, flyers/ brochures/ pamphlets, movies and internet. Then, the following survey item inquired whether the chosen source was mainly accessed in English or in Spanish. English sources were coded as mainstream media and Spanish sources were coded as ethnic media. It is important to note that the current study did not estimate general media consumption, as the main focus was on health-related sources of information.

Control variables

Several relevant health-related and sociodemographic characteristics that were theoretically related to either obesity or eating disorders were measured, including age, household income, number of children, education, employment status, marital status, years living in the community, English fluency, perceived stress, fruit and vegetable intake, fast food consumption, and health coverage. Specifically, English fluency was measured with a 4-point scale, where 1 meant “very poorly” and 4 meant “very well,” asking respondents how well do they speak English. The fruit and vegetables intake measurement was a composite of the two items – “how many servings of fruit do you usually eat or drink each day?” and “how many servings of vegetables do you usually eat or drink each day?” Fast food consumption was gauged by asking respondents “how many times did you eat fast food for breakfast?”, “how many times did you eat fast food for lunch?” and “how many times did you eat fast food for dinner?” in the past seven days. Health coverage was assessed with the binary item, “do you currently have any kind of health care coverage?” Finally, given its role in emotional eating and hypertension (for a discussion see Johnson and Wardle 2005), the survey included a self-reported measurement of perceived stress. In particular, respondents’ level of perceived stress was gauged with a 10-point scale, asking “how much stress did you have in your life in the past year?”

Statistical Analysis

First, descriptive statistics and bivariate associations were calculated based on the two BMI categories – obese and not obese. To examine health-related social ties and media preference as predictors of obesity and hypertension, two hierarchical binary-logistic regressions were conducted. Demographic and health-related factors were entered at block 1, health-related ties were added in block 2, media preference was introduced in block 3, and the interaction between health-related social ties and media preference was estimated in block 4. SPSS v20 was used to analyze the data.

Results

Table 1 summarizes respondents’ demographic and health-related factors by BMI category. The majority of the sample were not born in the U.S. (67.9%), immigrating from Mexico (70.5%), El Salvador (16.3%), Guatemala (12.7%), and Honduras (2.5%). Further, 35.4% of the sample were married, 32.1% were single (never married), and 21.4% reported on living with a partner. In terms of employment status, 28.7% were full time employed, 24% were homemakers, 21.8% were part time employed and the remaining 25.5% were divided between self-employed, laid off, students, and respondents who were permanently disabled. Of the total sample, 180 (49.5%) respondents were identified as obese and 184 (50.5%) respondents were identified as not obese. In terms of blood pressure, 154 (42%) respondents were characterized as suffering from hypertension, whereas 210 (58%) were in the non-hypertension category. On average, respondents had 1.88 (SD = 1.32) health-related social ties. As expected, the majority of health ties were associated with female friends (27.8%), followed by sisters (18.5%), mothers (13.4%), daughters (8.2%), and other female relatives (7.4%). In terms of health-related information sources, the sample showed a clear preference toward television (46.1%), internet (34.2%), and brochures (28.6%). Interestingly, there was no correlation between language preference (English/Spanish) and types of information sources. Nonetheless, as one might expect, the preliminary analysis recorded strong interdependence between language preference and English fluency, χ2(3) = 256.20, p = .001, Rc = .84; language preference and U.S. nativity χ2(1) = 182.97, p = .001, Φ = .71; English fluency and U.S. nativity, χ2(3) = 189.42, p = .001, Rc = .72; and only weak association between language preference and health coverage, χ2(1) = 11.12, p = .001, Φ = .18; English fluency and health coverage χ2(3) = 15.01, p = .002, Rc = .20; and U.S. nativity and health coverage, χ2(1) = 9.91, p = .002, Φ = .17.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Research Variables by BMI Category

| Variables | Full Sample (N = 364) |

Obese (N = 180) |

Not Obese (N = 184) |

Test of significance and p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 35.07(9.46) | 36.67(9.05) | 33.50(9.61) | t = 3.24*** |

| Years in the community | 11.27(9.20) | 12.33(9.38) | 10.24(8.93) | t = 2.18* |

| Number of children | 2.04(1.72) | 2.42(1.74) | 1.68(1.62) | t = 4.18*** |

| Education | 12.96(6.33) | 12.64(6.54) | 13.27(6.11) | t = 0.94 |

|

Household income X ≤ 20k 20k < X ≤ 40k 40k < X ≤ 60k 60k < X |

68.3% 21.3% 6.7% 3.7% |

69.9% 18.7% 6.6% 4.8% |

67% 23.8% 6.9% 2.3% |

χ2 = 0.59 |

|

Health coverage Yes |

39.6% |

42.8% |

36.4% |

χ2 = 1.54 |

| English fluency | 2.30(1.23) | 2.38(1.25) | 2.22(1.21) | t = 1.24 |

|

Language of survey Spanish |

59.9% |

64.4% |

55.4% |

χ2 = 3.08 |

| Born in the U.S. | 32.1% | 30% | 34.2% | χ2 = 0.39 |

|

Family’s country of origin1 Mexico El Salvador Guatemala Honduras |

70.5% 16.3% 12.7% 2.5% |

70.6% 14.4% 12.2% 2.8% |

70.5% 18% 13.1% 2.2% |

χ2 = 4.24 |

|

Marital status Married Separated Divorced Widowed Single (never married) Living with partner |

35.4% 5.2% 3.8% 1.9% 32.1% 21.4% |

37.8% 5.6% 2.2% 2.2% 27.2% 25% |

33.2% 4.9% 5.4% 1.6% 37% 17.9% |

χ2 = 8.04 |

|

Employment status Full time Part time Self-employed Laid off Homemaker Student Permanently disabled |

28.7% 21.8% 8.8% 5.5% 24% 9.9% 1.4% |

31.7% 18.9% 8.3% 6.1% 26.1% 7.8% 1.1% |

25.7% 24.6% 9.3% 4.9% 21.9% 12% 1.6% |

χ2 = 5.34 |

| Level of stress | 7.42(2.45) | 7.62(2.46) | 7.22(2.43) | t = 1.54 |

| Fruit & vegetables intake | 2.16(1.30) | 2.06(1.30) | 2.25(1.31) | t = 1.34 |

| Fast-food consumption | 0.80(0.98) | 0.82(1.03) | 0.78(0.93) | t = 0.40 |

| Number of health-related social ties | 1.88(1.32) | 1.74(1.19) | 2.02(1.42) | t = 2.02* |

|

Health ties Female friend Sister Mother Daughter Female relatives Husband Female co-worker Female cousin Partner |

27.8% 18.5% 13.4% 8.2% 7.4% 5.5% 3.4% 3.4% 3.1% |

24.5% 19.7% 13.7% 9.2% 5.7% 7% 3.5% 3.5% 3.8% |

30.6% 17.5% 13.2% 7.3% 8.9% 4.3% 3.2% 3.2% 2.4% |

χ2 = 19.73 |

|

Sources of health information1 Television Radio Newspapers Magazines Brochures Internet Community organizations |

46.1% 9.5% 3.4% 8.9% 28.6% 34.2% 7% |

49.8% 9.1% 3.7% 7.8% 29.6% 29.6% 6.6% |

42.5% 9.8% 3.1% 9.8% 27.6% 38.6% 7.5% |

χ2 = 2.65 |

|

Media preference Mainstream media |

56% |

63.3% |

48.9% |

χ2 =7.68*** |

Note: Group comparisons (obese versus not obese) are chi-square analyses for categorical variables and independent samples t-tests for continuous measures;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001; degrees of freedom (df) are 362 for t-tests. Due to the existence of minor categories, the percentages for certain variables do not add up to 100%.

The percentages provided for these variables sum to more than 100% because respondents could choose more than one answer option.

Compared to obese individuals, not obese Latinas tended to be younger and to have lived fewer years in their communities; they were also less likely to have children, more likely to be part-time employed rather than full-time employed, and more likely to be single. Interestingly, there were no significant differences across the BMI categories, with regard to fruit and vegetables intake, as well as fast-food consumption.

Obesity and hypertension as predicted by health-related social ties

H1a predicted that an increase in network ties would result in a reduced likelihood of obesity. As expected, controlling for relevant sociodemographic and health-related factors (for a complete list see Tables 2–3), social ties tended to reduce the likelihood of obesity (OR = .79, p = .014, 95% CI [.66, .95]). Specifically, on average, obese respondents tended to list 1.74 (SD = 1.19) individuals with whom they discuss issues related to health, whereas not obese respondents listed on average 2.02 (SD = 1.42). These differences were also statistically significant; t(362) = 2.02, p = .03). In contrast with H1b, controlling for relevant covariates, increase in health-related social ties was not significantly associated with a reduced likelihood for hypertension (OR = .98, p = .748, 95% CI [.81, 1.31]). Still, on average; t(362) = 2.39, p = .02), respondents with normal blood pressure tended to have more health-related social ties (M = 2.09, SD = 1.32) than their counterparts with hypertension (M = 1.75, SD = 1.30). See Tables 2–3 for a full layout of the regression, including odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2.

95% CI for Odds Ratio for the Prediction of obesity by Health-Related Social Ties and Media preference, Controlling for Health and Sociodemographic Factors

| Predictor | Block 1 OR |

Block 2 OR |

Block 3 OR |

Block 4 OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | .14 | .18 | .18 | .15 |

| Age | 1.03 [.99,1.06] |

1.03 [.99, 1.06] |

1.03 [.99, 1.06] |

1.03 [.99, 1.06] |

| Years in the community | 1.03 [.99, 1.05] |

1.03 [1.00,1.05] |

1.02 [.99, 1.05] |

1.03 [1.00,1.05] |

| Number of children | 1.26**

[1.07,1.50] |

1.28**

[1.08,1.51] |

1.28**

[1.08, 1.52] |

1.27**

[1.07, 1.51] |

| Education | 1.01 [.96, 1.05] |

1.02 [.97, 1.06] |

1.02 [.98, 1.07] |

1.02 [.97, 1.07] |

|

Household income |

.97 [.82, 1.16] |

1.01 [.85, 1.20] |

1.02 [.86, 1.22] |

1.02 [.85, 1.21] |

| Health coverage | .79 [.49, 1.26] |

.73 [.45, 1.17] |

.71 [.44, 1.15] |

.72 [.45, 1.17] |

| English fluency | 1.06 [.79, 1.42] |

1.07 [.80, 1.43] |

.96 [.70, 1.31] |

.94 [.68, 1.29] |

| Born in the U.S. | .90 [.46, 1.76] |

.88 [.45, 1.73] |

.81 [.41, 1.62] |

.81 [.40, 1.61] |

| Fruit & vegetables intake | .88 [.75,1.05] |

.91 [.76, 1.09] |

.91 [.76, 1.09] |

.92 [.77, 1.10] |

| Fast-food consumption | 1.12 [.87, 1.43] |

1.14 [.89, 1.46] |

1.15 [.89, 1.48] |

1.15 [.89, 1.49] |

|

Marital status Married Separated Divorced Widowed Single (never married) |

.62 [.33, 1.16] .55 [.19, 1.61] .18* [.05, .73] .50 [.09, 2.80] .60 [.31, 1.17] |

.62 [.33, 1.17] .60 [.20, 1.75] .18* [.04, .69] .58 [.10, 3.35] .56+ [.29, 1.10] |

.63 [.34, 1.20] .64 [.22, 1.93] .18* [.05, .71] .56 [.10, 3.27] .62 [.31, 1.22] |

.63 [.33, 1.19] .63 [.21, 1.89] .19* [.05, .72] .61 [.10, 3.59] .61 [.31, 1.22] |

|

Employment status Full time Part time Self employed Laid off Homemaker Student |

2.37 [.34,16.70] 1.54 [.22,10.82] 1.06 [.14, 8.23] 2.57 [.31,21.14] 1.88 [.27,13.23] 2.16 [.27,17.26] |

2.11 [.29,15.15] 1.49 [.21,10.58] 1.17 [.15, 9.28] 2.36 [.28,19.68] 1.74 [.24,12.43] 1.95 [.24,15.86] |

1.99 [.28, 14.01] 1.43 [.21, 10.11] 1.01 [.13, 7.86] 2.19 [.27, 17.90] 1.70 [.24, 11.95] 1.89 [.24, 15.13] |

1.82 [.25, 13.13] 1.32 [.18, 9.50] 1.01 [.13, 8.09] 2.05 [.25, 17.16] 1.63 [.23, 11.68] 1.68 [.20, 13.84] |

| Level of stress | 1.03 [.94, 1.13] |

1.03 [.94, 1.13] |

1.02 [.93, 1.12] |

1.01 [.92, 1.12] |

| Health-related social ties | .79**

[.66, .95] |

.80*

[.67, .97] |

.93 [.72, 1.22] |

|

|

Media preference Mainstream media |

1.85+

[.99, 3.43] |

3.27* [1.28, 8.33] |

||

| Social ties X Media preference | .75*

[.52, .97] |

|||

| R2 (Cox & Snell/ Nagelkerke) | .11/.14 | .12/.16 | .13/ .18 | .14/ .18 |

| R2 (Hosmer & Lemeshow) | .13 | .15 | .16 | .17 |

| Model χ2 | 40.84** | 47.43*** | 51.32*** | .53.92*** |

Note: [] are 95% CIs for ORs. Living with partner was the reference category for marital status and permanently disabled was the reference category for employment status;

p < .10

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Table 3.

95% CI for Odds Ratio for the Prediction of Hypertension by Health-Related Social Ties and Media preference, Controlling for Health and Sociodemographic Factors

| Predictor | Block 1 OR |

Block 2 OR |

Block 3 OR |

Block 4 OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.32 | 1.34 | 1.42 | .15 |

| Age | 1.04**

[1.01,1.07] |

1.04**

[1.01, 1.07] |

1.03** [1.01, 1.06] |

1.04**

[1.01, 1.06] |

| Years in the community | .99 [.98, 1.02] |

.99 [.98,1.02] |

.97 [.98, 1.02] |

1.01 [.98,1.02] |

| Number of children | .82**

[.72,.93] |

.82**

[.72,.93] |

.83**

[.72, .93] |

.82**

[.72, .94] |

| Education | .94**

[.91, .98] |

.95**

[.90, 97] |

.94**

[.91, .98] |

.94**

[.91, .98] |

|

Household income |

.95 [.82, 1.10] |

.95 [.82, 1.11] |

.94 [.81, 1.09] |

1.02 [.85, 1.21] |

| Health coverage | .48***

[.33,.70] |

.48***

[.33, .71] |

.48***

[.33, .70] |

.49***

[.34, .71] |

| English fluency | .93 [.73, 1.17] |

.92 [.73, 1.17] |

.98 [.76, 1.26] |

1.01 [.78, 1.29] |

| Born in the U.S. | 1.35 [.77, 2.38] |

1.35 [.77, 2.39] |

1.43 [.80, 2.54] |

1.48 [.83, 2.63] |

| Fruit & vegetables intake | 1.03 [.89,1.19] |

1.03 [.89, 1.21] |

1.03 [.89, 1.19] |

1.03 [.89, 1.19] |

| Fast-food consumption | 1.06 [.86, 1.31] |

1.06 [.86, 1.30] |

1.06 [.86, 1.31] |

1.05 [.85, 1.30] |

|

Marital status Married Separated Divorced Widowed Single (never married) |

.92 [.55, 1.52] 1.48 [.63, 3.47] 1.17 [.40,3.46] 2.58 [.32, 20.8] 1.21 [.70, 2.10] |

.92 [.55, 1.58] 1.48 [.63, 3.48] 1.17 [.40, 3.42] 2.57 [.32, 20.7] 1.21 [.70, 2.10] |

.91 [.55, 1.51] 1.44 [.61, 3.39] 1.14 [.39, 3.37] 2.67 [.30, 21.72] 1.18 [.68, 2.04] |

.91 [.55, 1.52] 1.45 [.61, 3.42] 1.12 [.38, .3.33] .2.67 [.33, 21.59] 1.18 [.68, 2.05] |

|

Employment status Full time Part time Self employed Laid off Homemaker Student |

1.37 [.36,5.21] 2.16 [.56,8.38] 2.04 [.45, 9.18] 3.17 [.72,13.97] 2.26 [.58,8.76] 1.77 [.39,7.94] |

1.37 [.40,5.23] 2.18 [.56,8.46] 2.07 [.46, 9.39] 3.17 [.72,13.98] 2.27 [.59,8.83] 1.77 [.40,7.96] |

1.40 [.37, 5.30] 2.20 [.57, 8.50] 2.16 [.48, 9.75] 3.25 [.74, 14.32] 2.30 [.59, 8.89] 1.77 [.40, 7.97] |

1.41 [.37, 5.40] 2.20 [.57, 8.58] 2.10 [.46, 9.53] 3.30 [.74, 14.65] 2.24 [.58, 8.70] 1.80 [.40, 8.12] |

| Level of stress | 1.01 [.93, 1.08] |

1.01 [.92, 1.08] |

1.01 [.93, 1.08] |

1.02 [.93, 1.09] |

| Health-related social ties | .98 [.85, 1.12] |

.97 [.84, 1.11] |

.82+

[.66, 1.01] |

|

|

Media preference Mainstream media |

1.46+ [.98, 1.94] |

1.34* [1.01, 1.78] |

||

| Social ties X Media preference | .79*

[.55, .98] |

|||

| R2 (Cox & Snell/ Nagelkerke) | .05/.09 | .06/ .10 | .07/ .11 | .08/.13 |

| R2 (Hosmer & Lemeshow) | .08 | .09 | .10 | .12 |

| Model χ2 | 54.97*** | 58.07 | 59.24 | 71.27*** |

Note: [] are 95% CIs for ORs. Living with partner was the reference category for marital status and permanently disabled was the reference category for employment status;

p < .10

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Obesity and hypertension as predicted by media preference

Latin American women exposed to mainstream media were more likely to be obese, however, this predictor had only borderline statistical significance (OR = 1.85, p = .07, 95% CI [.99, 3.43]). Interestingly, while the distribution of media preference for not obese individuals was almost identical for mainstream and ethnic media (48.9%, 51.1%, respectively), among obese individuals mainstream media appeared to be more salient than ethnic media as a source of health-related information (63.3%, 36.7%, respectively). Similarly, though respondents with hypertension tended to prefer mainstream upon ethnic media (59%, 40.7%, respectively), these differences were not statistically significant predictors of hypertension (OR = 1.46, p = .09, 95% CI [.98, 1.94]).

Interaction between health-related social ties and media preference

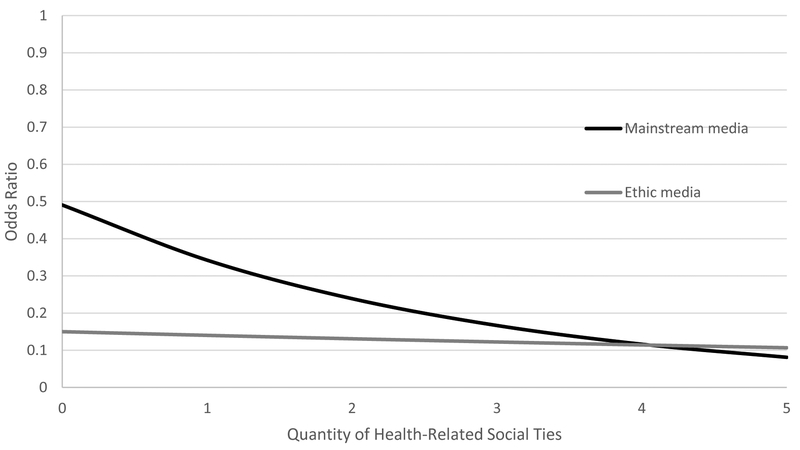

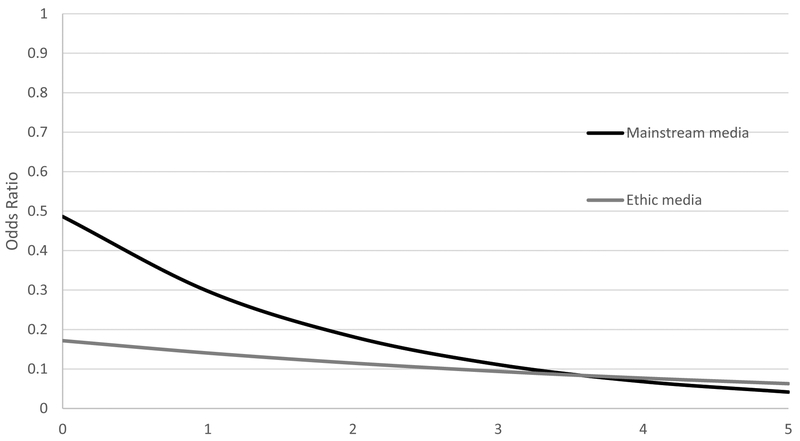

H3a-H3b predicted that ethnic media could compensate for absence of health-related social ties. The binary-logistic regression supports this hypothesis indicating that the interaction between health-related social ties and media exposure was associated with a decrease in likelihood for obesity (OR = .75, p = .041, 95% CI [.52, .97]). Figure 1 offers an interpretation to the pattern that emerges from this significant interaction. Namely, with respect to the likelihood of obesity, the number of health-related social ties an individual has seems to matter less for those who primarily use ethnic media as a resource for health information, compared to those who use mainstream sources. Indeed, in the latter scenario, each additional person in the health-related social network is associated with a considerable reduction in the likelihood for obesity as shown in Figure 1. Finally, a similar pattern emerges from the interaction effect of health-related social ties and media preference on hypertension (OR = .79, p = .045, 95% CI [.55, .98]). Simply put, the importance of health-related social ties is much more pronounced for Latinas who prefer mainstream sources, compared to those who prefer ethnic media (for details see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The Interaction Effect for Health-Related Social Ties and Media Preference (Mainstream/ Ethnic) On Likelihood of Obesity in Odds Ratio

Figure 2.

The Interaction Effect for Health-Related Social Ties and Media Preference (Mainstream/ Ethnic) On Likelihood of Hypertension in Odds Ratio

Discussion

Given the steeply rising obesity rates in the United States and the risk factors associated with hypertension generally and in Latino communities more specifically, the results of the current study provide some important insights. Although our data is correlational and thus no causal claim can be made from our results, they do support prior research that shows that an increase in social ties results in improved health outcomes (Murphy et al. 2013). Moreover, though consumption of ethnic media was only partially linked to the likelihood of obesity, it played a moderating role. Simply put, exposure to ethnic media mitigates the relative importance of individual’s social network. To this end, ethnic media may be a powerful tool for interventions, one that is capable of both filling in for a friend or family member in an individual’s life and also providing trusted and vital health information tailored to that person’s cultural background. Either by the social support that it provides or the sheer exposure to accessible and relevant health-related information, ethnic media can work to reduce health disparities.

Though dietary choices are usually considered to be an important predictor of obesity and hypertension, these relationships were not recorded in this sample. To some extent, this gap can be attributed to the fact that the vast majority of respondents came from low income families (68.3% reported on a combined household income of less than 20k). As argued by Drewnowsky and Darmon (2005), food choices are deeply related to socioeconomic status, which may override the contribution of other factors usually perceived as predictors of obesity in middle and upper class households.

These findings are subject to limitations. Non-random sampling was used to recruit participants, which could reduce our ability to generalize the results. However, because the population is a difficult to access, vulnerable group, we considered non-random sampling to be the best way to gain access to a diverse sample that was still representative of the population we were trying to study. Prior work has shown that persisting with random sampling techniques, such as random digit dial, when dealing with vulnerable populations, can result in a heavy overrepresentation of individuals with high levels of acculturation and education (Murphy et al. 2013). The cross-sectional nature of the data warrants the consideration of alternative explanations. For instance, another explanation for the finding that non-obese women tend to have more health-related social ties than obese women is that non-obese women are more comfortable discussing health-related topics with their friends and family compared to obese women. Further, the cross-sectional data provided in this study does not permit a close examination of the interplay between media preferences, acculturation, obesity, and hypertension. As less acculturated women have shown to have a lower prevalence of obesity than more acculturated women, their media preference, social ties, and health-related status (e.g., obesity) may be determined by their level of acculturation rather than the predictors examined in the current study.

In addition, though BMI is the most widely used measure to diagnose obesity, its accuracy has been often challenged (for a discussion see Prentice and Jebb 2011; Romero-Corral et al. 2008). Indeed, measurements based on actual body fat mass might have provided a more valid indicator of obesity. However, given its prevalence in public health research, ease of use, and the relative invasiveness of alternative measurements, we considered BMI to be the most appropriate surrogate measure of body composition.

Further limitations are associated with the difficulty to conceptualize media preference and use. Prior (2009) showed that people over-report the number of hours they spend watching the news; this biases the results against other media sources such as radio and newspaper which people are less likely to over-report. It is also difficult to accurately define ‘consumption’ of media, since a person could spend an hour in a room where the news played on the television in the background or an hour avidly focused on reading a newspaper and both hours would be equally weighted. Thus, the ethnic/ mainstream media binary was set up in the study to avoid attempts to measure exact amounts of time spent on each media source; it was instead designed to identify which media type (ethnic or mainstream) individuals preferred to collect health information from. The binary attempted to measure which media source was perceived as more valuable overall, by participants. Likewise, in order to ensure that the media binary we crafted was not missing subtler behavior patterns that could be based in use of specific media types and not others, we ran a post hoc analysis that added the information sources to the regression as dummy variables. The type of source did not make a significant difference, suggesting that it is not the source per se but rather the language in which the information is communicated that is linked to a reduced likelihood of the incidence of obesity. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that the binary measure cannot illuminate many of the important questions that our findings raise. For instance, what is the unique contribution of exposure to Spanish/English language media on the relationship between health-related social ties and obesity/hypertension? Finally, it may be useful to delve with greater depth into the nature of the health-related social ties. The distributions of health-related ties in the current study suggest that Latinas talk about their health, predominantly, with other females. To this end, future studies could explore whether mechanisms of homophily also hold for other variables, such as race, ethnicity, and immigration status.

Public health researchers often argue that the most feasible, and often most effective interventions are those that build on the resources already available in the community. These researchers believe that people in a community understand their own needs, as well as the barriers they face, better than outsiders. The results of this study align with that logic, as the lowest likelihood of obesity and hypertension occurred in Latina women that preferentially accessed ethnic media rather than mainstream media and were better situated to discuss their health with similar others. This study adds to our understanding of the cultural and socioeconomic correlates of obesity and hypertension by showing the potential impact that ethnic media can have in this population.

References

- Aldrich Daniel P. 2012. Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- American Heart Association. 2017. Understanding Blood Pressure Reading. Available at: http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HighBloodPressure/AboutHighBloodPressure/Understanding-Blood-Pressure-Readings_UCM_301764_Article.jsp#/Accessed January 20, 2017.

- Ball-Rokeach Sandra J. 1998. “A Theory of Media Power and a Theory of Media Use: Different Stories, Questions, and Ways of Thinking.” Mass Communication & Society. 1(1–2): 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Berland Gretchen K., Elliott Marc N., Morales Leo S., Algazy Jeffrey I., Kravitz Richard L., Broder Michael S., Kanouse David E. et al. 2001. “Health Information on the Internet: Accessibility, Quality, and Readability in English and Spanish.” Jama 285 (20): 2612–2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015a. Prevalence of Self-Reported Obesity Among Hispanic Adults by State and Territory, BRFSS, 2012–2014. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/table-hispanics.html/ Accessed March 2, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015b. Department of Health and Human Services: Healthy Weight. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/ Accessed April 9, 2016.

- Cutler Jeffrey A., Sorlie Paul D., Wolz Michael, Thom Thomas, Fields Larry E., and Roccella Edward J.. 2008. “Trends in Hypertension Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control Rates in United States Adults between 1988–1994 and 1999–2004.” Hypertension 52 (5): 818–27. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.113357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derose K P, and Baker DW. 2000. “Limited English Proficiency and Latinos’ Use of Physician Services.” Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR 57 (1): 76–91. doi: 10.1177/107755870005700105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski Adam, and Darmon Nicole. 2005. “Symposium : Modifying the Food Environment : Energy Density, Food Costs, and Portion Size Food Choices and Diet Costs : An Economic Analysis 1, 2” The Journal of Nutrition, 900–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores Glenn, Lin Hua, Walker Candy, Lee Michael, Portillo Alberto, Henry Monica, Fierro Marco, and Massey Kenneth. 2016. “A Cross-Sectional Study of Parental Awareness of and Reasons for Lack of Health Insurance among Minority Children, and the Impact on Health, Access to Care, and Unmet Needs.” International Journal for Equity in Health 15 (44). doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0331-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter Mark. S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology 78(6): 1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson F, and Wardle J. 2005. “Dietary Restraint, Body Dissatisfaction, and Psychological Distress: A Prospective Analysis.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(1): 119–25. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kell Kenneth P, Michelle I Cardel, Michelle M Bohan Brown, and Jose R Fernandez. 2014. “Added Sugars in the Diet Are Positively Associated with Diastolic Blood Pressure and Tiglycerides in Cihldren.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 100 (3): 46–52. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.076505.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley Megan S., Su Dejun, and Britigan Denise H.. 2016. “Disparities in Health Information Access: Results of a County-Wide Survey and Implications for Health Communication.” Health Communication 31 (5): 575–82. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.979976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatib R, Schwalm JD, Yusuf S, Haynes RB, McKee M, Khan M and Nieuwlaat R, 2014. “Patient and Healthcare Provider Barriers to Hypertension Awareness, Treatment and Follow Up: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Qualitative and Quantitative Studies. PloS One, 9 (1), p.e84238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Yong-Chan, and Ball-Rokeach Sandra J.. 2006. “Community Storytelling Network, Neighborhood Context, and Civic Engagement: A Multilevel Approach.” Human Communication Research 32 (4): 411–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2006.00282.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos Emily, Blake Kelly D., Wen Ying Sylvia Chou, and Prestin Abby. 2014. “Predictors of Ehealth Usage: Insights on the Digital Divide from the Health Information National Trends Survey 2012.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 16 (7): 1–16. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner Mark, Greenburg Elizabeth, Jin Ying, Paulsen Christine, E Greenberg Ying Jin, and Paulsen Christine. 2006. “The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. NCES 2006–483.” National Center for Education Statistics 6: 1–59. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.5.282.33191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsaganis MD, Katz VS, and Ball-Rokeach SJ. 2010. Understanding Ethnic Media: Producers, Consumers, and Societies. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy Sheila T., Frank Lauren B., Chatterjee Joyee S., and Baezconde-Garbanati Lourdes. 2013. “Narrative versus Nonnarrative: The Role of Identification, Transportation, and Emotion in Reducing Health Disparities.” Journal of Communication 63 (1): 116–37. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Huong, Shiu Chengshi, and Peters Clark. 2015. “The Relationship between Vietnamese Youths’ Access to Health Information and Positive Social Capital with their Level of HIV Knowledge: Results from a National Survey.” Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies 10 (1): 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pardee Perrie E., Norman Gregory J., Lustig Robert H., Preud’homme Daniel, and Schwimmer Jeffrey B.. 2007. “Television Viewing and Hypertension in Obese Children.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 33 (6): 439–43. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitte Trisha, Mallow Jennifer, Barnes Emily, Petrone Ashley, Barr Taura, and Theeke Laurie. 2015. “A Systematic Review of Loneliness and Common Chronic Physical Conditions in Adults.” The Open Psychology Journal 8: 113–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, and Vickstrom Erik. 2011. “Diversity, Social Capital, and Cohesion.” The Annual Review of Sociology 37: 461–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice AM, and Jebb SA. 2001. “Beyond Body Mass Index.” Obesity Reviews: An Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 2(3): 141–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior Markus. 2009. “The Iommensely Inflated News Audience: Assessing Bias in Self-Reported News Exposure.” Public Opinion Quarterly 73 (1): 130–43. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfp002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Corral A, V K Somers J Sierra-Johnson RJ Thomas ML Collazo-Clavell J Korinek TG Allison JA Batsis F H Sert-Kuniyoshi, and Lopez-Jimenez F. 2008. “Accuracy of Body Mass Index in Diagnosing Obesity in the Adult General Population.” International Journal of Obesity (2005), 32 (6): 959–66. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen Larry D., Lim AF, Felt Julie, Mark Carrier L, Cheever Nancy A., Lara-Ruiz JM, Mendoza JS, and Rokkum J. 2014. “Media and Technology Use Predicts Ill-Being among Children, Preteens and Teenagers Independent of the Negative Health Impacts of Exercise and Eating Habits.” Computers in Human Behavior, 35: 364–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard Vanessa B., Karen Patricia Williams Judy Wang, Shavers Vickie, and Mandelblatt Jeanne S.. 2014. “An Examination of Factors Associated with Healthcare Discrimination in Latina Immigrants: The Role of Healthcare Relationships and Language.” Journal of the National Medical Association 106 (1): 15–22. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30066-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorlie Paul D., Allison Matthew A., Larissa Avilés-Santa M, Cai Jianwen, Daviglus Martha L., Howard Annie G., Kaplan Robert, et al. 2014. “Prevalence of Hypertension, Awareness, Treatment, and Control in the Hispanic Community Health Study/study of Latinos.” American Journal of Hypertension 27 (6): 793–800. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- State of Obesity. 2014. “Obesity Prevention in Latino Communities. Available at: http://stateofobesity.org/disparities/latinos/ Accessed February 20, 2016.

- Valente Thomas. W. 2012. “Network Interventions.” Science 337 (6090): 49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1217330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath K, and Arora P. 2000. “Ethnic Media in the United States: An Essay on their Role in Integration, Assimilation, and Social Control.” Mass Communication & Society 3(1): 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin Holley A., Katz Vikki S., Ball-Rokeach Sandra J., and Hether Heather J.. 2015. “Communication Resources for Obesity Prevention Among African American and Latino Residents in an Urban Neighborhood.” Journal of Health Communication 20 (6): 1–10. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon Sung Sug, Gu Qiuping, Nwankwo Tatiana, Wright Jacqueline D., Hong Yuling, and Burt Vicki. 2015. “Trends in Blood Pressure among Adults with Hypertension United States, 2003 to 2012.” Hypertension 65 (1): 54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]